Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the leading causes of death from cancer in the world. We now know that 90% of CRC develop from adenomatous polyps. Polypectomy of colon adenomas leads to a significant reduction in the incidence of CRC. At present most of the polyps are removed endoscopically. The vast majority of colorectal polyps identified at colonoscopy are small and do not pose a significant challenge for resection to an appropriately trained and skilled endoscopist. Advanced polypectomy techniques are intended for the removal of difficult colon polyps. We have defined a “difficult polyp” as any lesion that due to its size, shape or location represents a challenge for the colonoscopist to remove. Although many “difficult polyps” will be an easy target for the advanced endoscopist, polyps that are larger than 15 mm, have a large pedicle, are flat and extended, are difficult to see or are located in the cecum or any angulated portion of the colon should be always considered difficult. Although very successful, advanced resection techniques can potentially cause serious, even life-threatening complications. Moreover, post polypectomy complications are more common in the presence of difficult polyps. Therefore, any endoscopist attempting advanced polypectomy techniques should be adequately supervised by an expert or have an excellent training in interventional endoscopy. This review describes several useful tips and tricks to deal with difficult polyps.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Polypectomy, Mucosectomy, Colon polyp, Polyp, Endoscopic mucosal resection, Mucosectomy, Endoscopic submucosal dissection

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the leading causes of death from cancer in the world. We now know that 90% of CRC develop from adenomatous polyps[1]. Polypectomy of colon adenomas leads to a significant reduction in the incidence of CRC[1,2]. At present most of the polyps are removed endoscopically[2-5]. The vast majority of colorectal polyps identified at colonoscopy are small and do not pose a significant challenge for resection to an appropriately trained and skilled endoscopist[2-4]. Advanced polypectomy techniques are intended for the removal of difficult colon polyps. We have defined a “difficult colon polyp” as any polyp that due to its size, shape or location makes it difficult for the colonoscopist to remove[3]. Although many “difficult polyps” will be an easy target for the advanced endoscopist, polyps that are larger than 15 mm, have a large pedicle, and are flat and/or laterally spreading, are difficult to see or are located in the cecum or any angulated portion of the colon should be always considered difficult[3-7]. Although very successful, advanced resection techniques can potentially cause serious, even life-threatening complications[4-6]. Moreover, post polypectomy complications are more common in the presence of difficult polyps[5,6]. Therefore, any endoscopist attempting advanced polypectomy techniques should be adequately supervised by an expert or have an excellent training in interventional endoscopy. This review describes several useful tips and tricks to deal with difficult polyps.

PATIENT PREPARATION

The patient should undergo a detailed preoperative history and physical examination. The physician must inform the patient about the benefits and risks of colonoscopy and endoscopic polypectomy, including the risk of missing lesions and the risk of sedation. Routine preoperative laboratory blood testing is not indicated before polypectomy[3,4,8,9]. Blood testing should be done in patients suspected of harbouring a blood dyscrasia and those who are being treated with oral anticoagulants or heparin and its derivates[8]. Although there are limited data sowing no increased risk of bleeding after polypectomy in patients taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, aspirin or clopidogrel, most endoscopists ask the patient to stop these medications seven days before polypectomy[3,4,8,9]. A prerequisite for advanced polypectomy is an adequate bowel preparation. A clean bowel may prevent the development of an overwhelming peritonitis and sepsis should a perforation occur. The aim should be to perform advanced polypectomy only if the colon preparation reaches a Boston scale 2 or 3[10]. If the colon is inadequately prepared, we recommend repeating the procedure on another occasion. It is better to be safe than sorry!

DIFFICULT COLON POLYPS AND THEIR ENDOSCOPIC APPROACH

A difficult polyp is any flat or raised colonic mucosal lesion that due to its size, shape and location makes it difficult to remove[3,4,7,9] (Table 1) (Figures 1-5). Even the number of polyps might be considered a “difficult polypectomy” as the rate of significant complications increases with the number and complexity of polypectomies[3-6,11]. Polyp removal should follow a standardized approach. All the equipment and accessories employed for polypectomy should be readily available. Table 2 lists common accessories utilized during advanced polypectomy. We have a special cabinet in every room containing snares, needles, clips, endoloops and the material needed for submucosal cushion injection[12-16].

Table 1.

Defintion of difficult colon polyp

| Shape (morphology) | Flat or hard to see |

| Sessile > 15 mm | |

| Carpet shaped (laterally spreading tumor) | |

| Villous or granular | |

| Irregular surface, irregular pit pattern, villous or granular | |

| If pedunculated, thick or short pedicle | |

| Size | < 1.5 cm |

| Large > 3 cm | |

| Big head | |

| Number | Multiple (> 3) |

| Location | Right colon and cecum |

| Ileoceccal valve | |

| Appendix orifice | |

| On top or behind of folds | |

| Difficult endoscopic position |

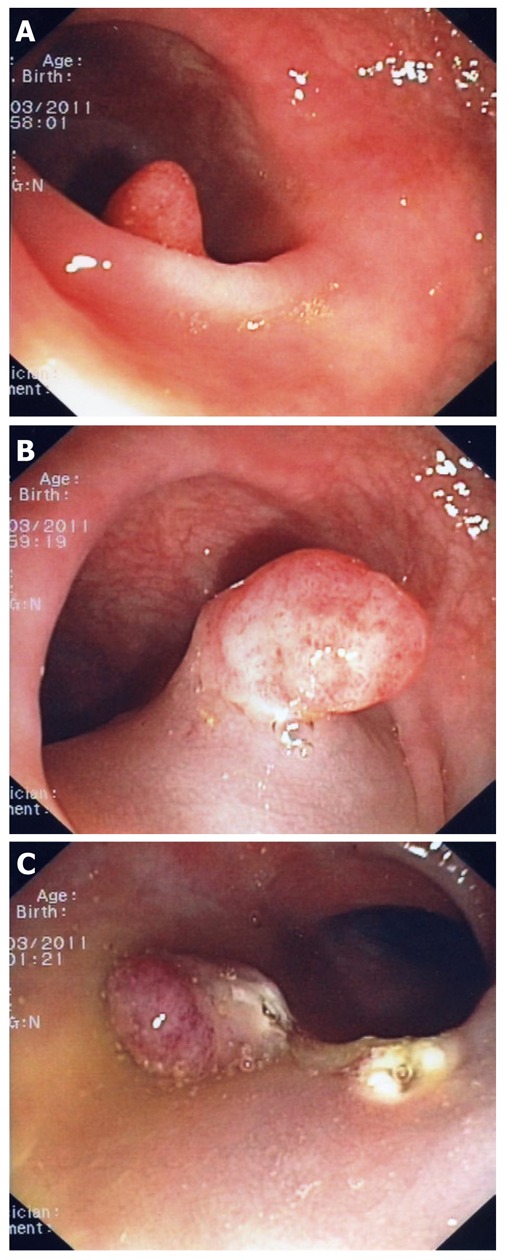

Figure 1.

Difficult polyp located “behind” a fold (A). A closer look indicates that this is a large sessile polyp (B). The polyp was resected using mucosectomy technique (C).

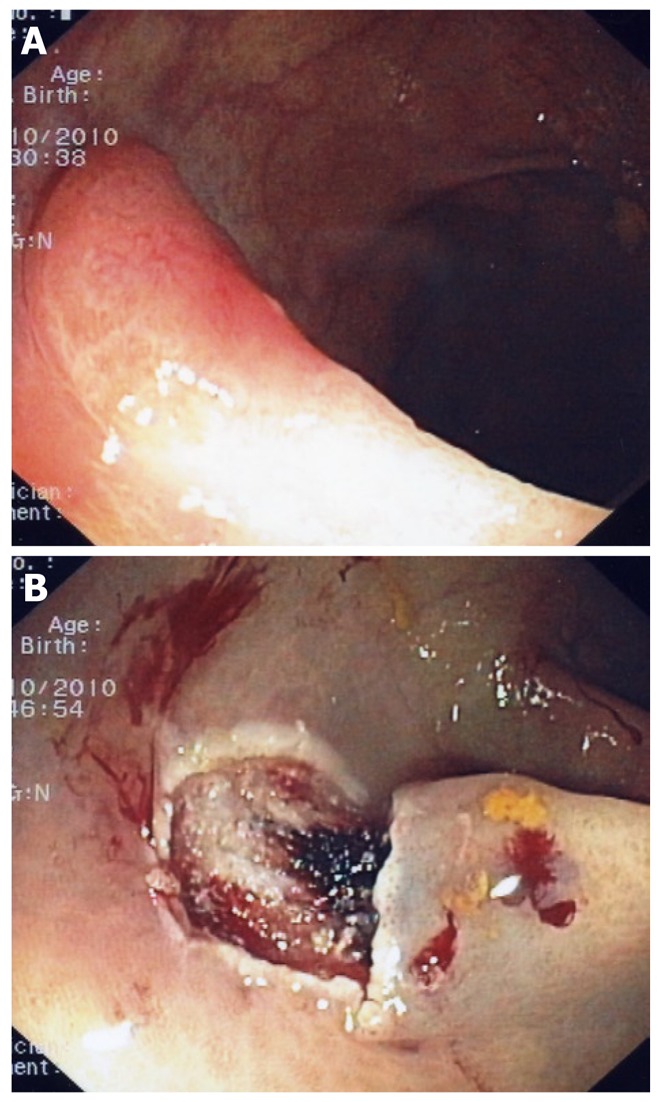

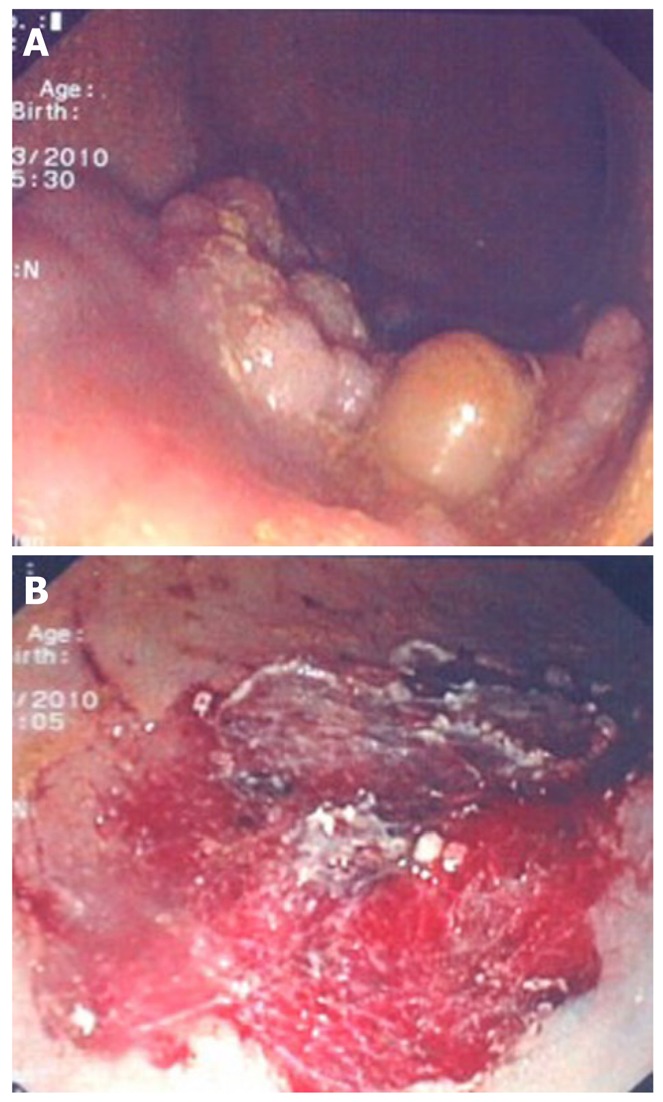

Figure 5.

Flat polyp with irregular vascular pattern (A). Mucosectomy site (B); This polyp contained invasive cancer. A subsequent laparoscopic segmental section of the colon was performed.

Table 2.

Nine steps leading to a successful polypectomy

| Locate of the polyp |

| Analyze the polyp’s shape |

| Determine the polyp’s size |

| Analysis of the polyp surface |

| Determine the number of polyps |

| Position the polyp before attempting its resection |

| Estimate polyp respectability using endoscopic methods |

| Use the submucosal cushion (injection-assisted-polypectomy) |

| Appropriate skills using clips and/or endoloops |

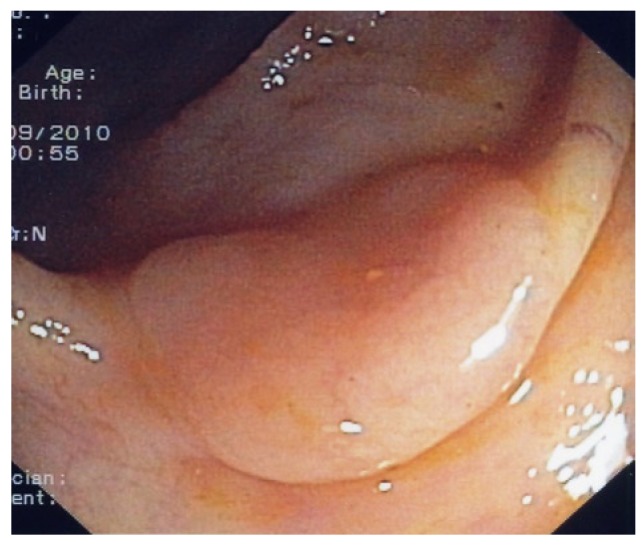

Figure 4.

Typical flat polyp located on top of a fold.

STEPS TO FOLLOW WHEN CONFRONTED WITH A DIFFICULT POLYP

There are eight important steps to follow, which should lead to a successful colon polyp resection, especially when confronted with difficult polyps. These are enumerated in Table 3 and will be discussed in subsequent order below. Table 4 lists some basic principles, tips and tricks when dealing with difficult colon polyps.

Table 3.

Accessories and utensils used in advanced polypectomy

| Hot biopsy forceps (we do not recommend to use hot biopsy forceps for colon polyp removal) |

| Single use |

| Resusable |

| Monofilament and braided wire snares of various diameters, e.g. mini < 11 mm, standard 15-45 mm) |

| Mini oval (recommended to remove diminutive polyps using the cold-snare technique, i.e. without heat of electrosurgical current) |

| Standard oval |

| Hexagonal |

| Crescent |

| Spiral |

| Mini barbed (the multiple barbs (help hold the tissue inside of the snare) |

| Needle-tip anchored (the needle tip on top the distal part of the snare helps stabilize the position of the snare, however the tip can lacerate the healthy mucosa) |

| With heat- resistant net (Nakao net) (not widely available) |

| Injection needle(s) |

| Injection substances (normal saline, hypertonic saline, dextrose 50%, adrenaline, sodium hyaluronidate |

| India ink (used for tattooing and marking) |

| Dyes (methylene blue, indigo carmine) |

| Combination needle/snare (allows for injection-assisted polypectomy and immediate snaring) |

| Rotatable snares (may be useful for polyps located in difficult luminal location, when the scope cannot be torqued to an ideal position) |

| Endoscopic fitted caps (allow the detection of polyp behind folds) |

| Without snare rim |

| With snare rim |

| Needle knifes (at least 20 different types available for endoscopic submucosal dissection) |

| Without insulated tip |

| With insulated tip |

| Flush-knife |

| Clips (hemoclips or endoclips) (single use or reusable) |

| Endoloops |

| Retrieval devices |

| Baskets |

| Nets (Roth net) |

| Grasping forceps with two to five prongs |

Table 4.

Technical tips and tricks to improve the resection of difficult colon polpys

| Difficult polyps | Technical tips | |

| Morphology | Sessile | Use submucosal cushion |

| > 1 cm | Resect in toto (except cecum) | |

| Size and form | < 1.5 cm | Use diluted epinephrine and Perform piecemeal resection, EMR or ESD |

| Large (> 3 cm), on top of folds, carpet-like polyp or with villous or granular surface | ||

| Use APC for tissue remnants | ||

| Big head | Use diluted epinephrine in head | |

| Pedunculated (if large) | Use clips or loops | |

| Thick pedicle | Use clips or loops | |

| Multiple | Send to pathologist separately | |

| Number | Right colon and cecum | Do not use hot biopsy forceps |

| Located behind folds | Inject distally first | |

| Location | Difficult endoscope position | Change scope to 5 o’clock position |

| Perform abdominal compression or change patient’s position | ||

| Use antispasmodic (e.g., butylscopolamine) | ||

| Take air out before catching or snaring the polyp | ||

| Resect when going in (if small) or when going out (if large) | ||

| Increased colon motility | Mark the polyp site with India ink | |

| General recommendations | Suspicious polyp or large, incompletely resected | |

| Abbreviations | APC | Argon plasma coagulation |

| ESD | Endoscopic submucosal dissection | |

| EMR | Endoscopic mucosal resection |

APC: Argon plasma coagulation; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection.

Location of the polyp

First, the location of the lesion shall be noted. Is the polyp located in the right or left colon? Because of the thinness of the wall, anatomically the ascending colon, the cecum and the descending colon are the most dangerous sides for polypectomy, especially when much air is insufflated. Polyps located in these locations should be treated with additional caution[3,4]. If the polyp is located in the dorsal or retroperitoneum side of the body, minor perforation may be managed conservatively. Thus it can be useful to change the patient’s position before the endoscopic treatment to confirm the site of the polyp. Polyps located in the rectum are prone to bleed more during or after resection, as the vascular supply to this area is very rich.

When using submucosal injection solutions with vasoconstrictors (i.e., adrenaline) or hypertonic mixtures are mandatory[3,4,9]. Taking out the air will also decrease tension on the wall, allow for better ensnaring of the polyp and increase the thickness of the underlying submucosal and muscular layers. When the polyp has been grasped it is imperative to create a “tent”. By doing so, the electrosurgical current will tend to remain at the proximal base of the polyp, decreasing the pressure of the snare (and hence electrical current) against the colon wall[4]. The endoscopist should also evaluate the relation of the polyp to the colonic folds (Figure 1). Polyps on top of folds should be always raised with a submucosal cushion as grabbing too much tissue with a snare could result in deep resection lesions leading to perforation. Also, larger polyps lying between two folds or extending beyond two folds shall always be removed using submucosal cushion and either piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) (see separate sections on submucosal cushion, EMR and ESD)[3-6].

Analyze the polyp’s shape

Although there is no foolproof method to categorically best define a lesion endoscopically, the most commonly used categorization is the Kyoto-Paris classification of gastrointestinal neoplasia[7]. It differentiates a type I protruding lesion (pedunculated, sessile), from a type II non-protruding, non-excavated lesion (slightly elevated, completely flat, slightly depressed) and excavated type IIIlesion[7]. However, this classification applies to all lesions of the entire gastrointestinal tract, including squamous and cylindrical mucosal neoplasia. The astute reader will notice that the Kyoto-Paris classification refers to “non-polypoid” lesions, i.e. it excludes sessile and pedunculated polyps. Thus, we prefer to call a polyp what it is (i.e., a polyp) and avoid complex terminology that can lead to more confusion. Moreover, this classification calls these “non-polypoid” structures “lesions” and in addition it also classifies many non-polypoid lesions as polypoid, sessile or pedunculated. Thus, we try to remain practical and stick to a simple description of a colon polyp[3,4]. One can differentiate between a pedunculated polyp (polyps with a stalk, stem, pedicle or peduncle) (Figure 2) and those without a pedicle (i.e., sessile polyps)[3] (Figure 3). The third type is the flat lesion (Figures 1, 4 and 5). For a flat or sessile polyp it is important to determine their base surface and spreading appearance (i.e., lateral growth), their surface (nodular or villous or mixed) and whether they have a central depression or ulceration. Baptizing these lesions with Roman numbers and alphabetical letters may not lead to a better endoscopic resection! Lesions larger than 15 mm should be resected using adjunctive techniques such as submucosal cushion or piecemeal methods[3-6] (Figures 1, 6 and 7). Excellent knowledge of the existing accessories, electrosurgical devices and electrical currents (i.e., endocut, coagulation, pure cut, blend) used to resect and retrieve polyps and to prevent complications is mandatory[3,4,11-19] (Table 3). Pure cutting and “blended” currents result in more immediate bleeding, whereas coagulation currents result in more post-polypectomy bleeding and transmural perforation[16-19]. We prefer to use true blended currents (endocut) or pure cutting currents as immediate bleeding can be easily treated with clip application or injection. Endocut is a true blended current as a computer located in the electrosurgical unit determines it[17]. We do not use hot biopsy techniques to remove any polyp or polyp remnants as this technique can result in transmural burn, especially in the cecum. In addition, the histopatholgical specimen is often “burned”[19].

Figure 2.

Large polyp located in the transverse colon (A). A closer inspection reveals that this polyp has a thick stalk (B); After injecting the stalk with adrenaline-saline mixture the snare was placed around it; Notice that the snare exits the scope at 5 o’clock position (C); A clip was placed at the base of the stalk to prevent post-polypectomy bleeding (D).

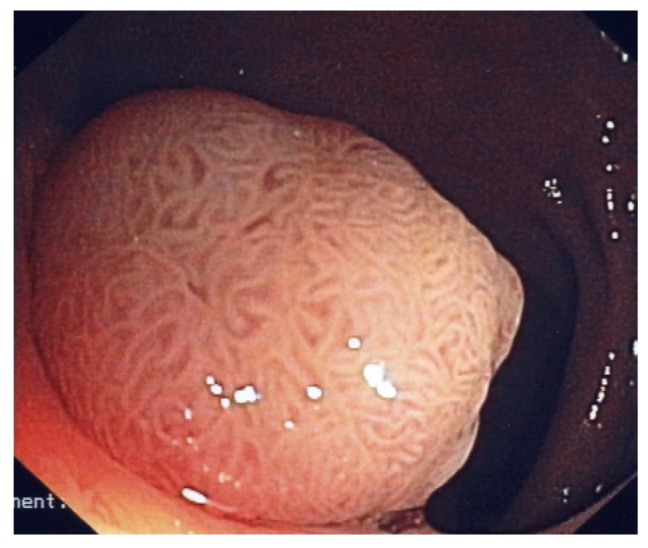

Figure 3.

Large sessile polyp with cerebriform pit-pattern. This polyp was an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia.

Determine the polyp’s size

There is no clear-cut definition for “large polyp”. However, polyps > 20 mm should be considered “large”, > 40 mm very large and > 50 mm “giant” (Figures 6 and 7). Size alone does not neglect resectability. This will rather depend on polyp location (cecum versus left colon, see above) and degree of neoplasia (i.e., invasive cancer). The degree of neoplasia can be often determined by inspecting the polyp surface (see separate paragraph below). Ulcerated polyps and those with a deranged pit-and vascular pattern should not be resected unless the aim is to perform a debulking procedure. Furthermore, polyps larger than 20 mm should be dealt with more caution, especially if these are flat or sessile. For polyps with a pedicle the most important aspect is, whether the stalk is thin or a thick or short or long. The advanced endoscopist should always aim at achieving an oncologic resection, i.e. the entire specimen should be removed. Thus, flat, and most sessile lesions measuring > 15-20 mm should be resected after the creation of a submucosal cushion (see separate paragraph on submucosal cushion below). This will ensure a safer margin of resection, possible reduce complications such as perforation and provide the pathologist with a good specimen to analyze. One of the most frustrating aspects of advanced colonoscopy is to send a specimen to the pathologist just to hear that the depth and lateral margins of the specimen could not be well seen due to cautery artefact and a superficial resection.

Figure 6.

Large sessile polyp (A) and polyp site after performing piece-meal mucosectomy (B).

Figure 7.

Sessile polyp located behind a fold (A), the creation of the submucosal cushion enabled the clear visualization of the polyp (B) and endoscopic resection site (C).

Analysis of the polyp surface

Make sure that the surface (pit-pattern) of the polyp is well investigated. Regular, cerebriform convolutions generally reflect an adenoma (Figure 3), whereas irregular, highly vascularised surface often indicates a carcinoma[7,20] (Figure 5). Whether the complex and constantly in evolution and modified pit-pattern classifications will help establish a clear-cut pre-operative diagnosis is still not clear[7,20]. We want to alert the advanced endoscopist that even polyps with a regular appearing surface can contain carcinoma! Furthermore, most hyperplastic-appearing lesions of the right colon are serrated adenomas or contain adenomatous elements and should thus be resected. In essence, and with the exception of submucosal lesions, we follow a policy of “I see and then resect”. However, chromoendoscopy and magnification endoscopy can be useful to help us characterize colon polyps and the advanced endoscopist should master the principles of these techniques.

Today, we differentiate between virtual and real chromoendoscopy methods[20]. Standard chromoendoscopy techniques include contrast (e.g., indigo carmine) and vital dyes or stains (e.g., methylene blue)[20] (Figure 8). Virtual chromoendoscopy methods such as narrow band imaging, “Fujinon intelligent chromoendoscopy” or Fujinon-enhanced color enhancement (FICE) or I- Scan avoid the use of dye spray[20-22] (Figure 9). These methods allow enhancing the mucosal (pit pattern) and submucosal capillary network detail, both of which can be deranged in the presence of a neoplasia.

Figure 8.

Flat polyp located in the rectum (A), demarcation of the polyp edges and surface with standard chromoendoscopy (indigo carmine) (B) and endoscopic mucosal resection site (C).

Figure 9.

Sessile polyp located in the transverse colon. Demarcation of the polyp margins and surface with standard chromoendoscopy (methylene blue) (A); Endoscopic mucosal resection site (B).

The results regarding polyp detection using virtual and/or standard chromoendoscopy are controversial[20-22]. However, the characterization of polyps can be enhanced using these methods. Nevertheless, the scant data available using the complex pit pattern or submucosal capillary pattern classifications do not support a crucial role of any chromoendoscopic method on the polypectomy-decision making process. The bottom line is that in practice we will not leave any polyp > 10 mm in situ just based on the pit pattern appearance. In addition, smaller polyps may also contain advance neoplasia or cancer. Whether a process of inspect, resect and discard based on a suspected endo-pathological diagnosis is worthwhile goes beyond the scope of this review paper which deals with advanced resection techniques for colon polyps[23].

Position of the polyp

The lumenal position of the polyp can be awkward and difficult its ensnarement. Always attempt to place the polyp at the 5 to 6 o’clock position, as this is the position were the snare and other accessories (e.g., needle, clips, etc.,) exit the scope. A useful rule is passing the scope far beyond the polyp, even as far as the cecum and then attempting capture during the withdrawal phase of the examination. Whenever a polyp is approached, snare placement is facilitated by rotation of the colonoscope, which brings the polyp in the 5 o’clock position[3,4]. An advantageous position may be best accomplished when the colonoscope shaft is straight, because a straight instrument transmits torque to the tip, whereas a loop in the shaft tends to absorb rotational motions applied to the scope. Other useful tips to improve polyp positioning are applying abdominal pressure and changing of the patient’s position. In exceptional situations a good positioning is not possible. Still, a careful polypectomy may be attempted while an assistant holds the scope in a stable position. Retroflexion is also a maneuver that can be carefully performed in any part of the colon and improve polypectomy success[24]. On the other hand changing scopes might be the best option (i.e., use a gastroscope, which has the opening of the accessory channel at the opposite position (7 o’clock position). Furthermore, utilizing the “double-scope” technique may result in a successful resection of complicated polyps[25,26].

Number of polyps

The number of colon polyps will determine the time and instruments to be used. If multiple polyps are present these and be collected as they are resected using a Roth’s net[3,4]. But even small polyps can contain an invasive carcinoma and so the location of the polyp can’t be transmitted to the pathologist. Some experts send all polyps separately. We recommend sending all polyps separately. The worst-case scenario is to have the pathologist inform the endoscopist of an invasive cancer and not to know whether it was located. We limit the number of polypectomies during one session to no more than 10 and we remove the remaining polyps during following sessions.

Estimation of polyp resectability

This is the result of summarization and feasibility analysis of the above-mentioned steps. Currently, the rules for endoscopic resection have changed. Whereas in the past several criteria clearly mandated surgery (i.e., polyp extending more than 1/3 of the luminal circumference, extending more than two folds location on the ileocecal valve, large, flat villous tumors), currently these criteria are not a contraindication for endoscopic polypectomy anymore. We have entered an era of grey-zones, but with the exception of giant polyps located in the cecum, and the increase skills attained by advanced endoscopists, the majority of colonic polyps can be resected endoscopically (Figures 8-10).

Figure 10.

Giant rectal polyp (A), the polyp was resected using endoscopic submucosal dissection-technique (B) and an en-bloc resection was possible (C).

Submucosal cushion (injection-assisted-polypectomy)

Submucosal injection is suggested for the colonoscopic resection of a sessile polyp over 15 mm in diameter[3,4,6,9,27-30] (Figure 1). However, any polyp can be removed using injection-assisted polypectomy (IAP). Indeed, some experts propose its use for all polyps on two main grounds: (1) achieving a more complete resection; and (2) diminishing the risk of complications such as perforation, bleeding and transmural burn. Thus, it is also reasonable to use IAP for any polyp that is flat, regardless of its size. By raising the polyp from the submucosa a deeper and more complete resection of the neoplastic tissue can be achieved[3,4,6,9,27-30]. In addition, by lifting the submucosa from the deeper layers of the gut wall, the depth of injury is decreased by avoiding the burn at the muscularis propria and serosa[28]. However, submucosal injection even with a large amount of fluid may not avoid perforation if overly large pieces of the polyp are ensnared and resected. Multiple substances are commercially available to perform an IAP. We recommend the use of it for polyps larger than 15 mm. Normal saline is the most popular fluid to IAP. But one can also use a saline-diluted epinephrine mix, saline and dextrose 50% mix, normal saline and methylene blue mixture, sodium hyaluronidate, fibrinogen and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose[3,4,6,27-30]. Some data showing a longer lasting cushioning effect of a normal saline and dextrose mix[29]. We recommend a saline-diluted adrenaline mix (1:10 000) in all parts of the colon, except the cecum, due to the possibility of inducing an ischemic colitis using epinephrine in the cecum. Prophylactic injection of submucosal saline-adrenaline for colon polyps larger than 10 mm is associated with less bleeding and a more complete removal of larger polyps, especially when using the piece-meal resection technique.

TECHNIQUE FOR THE CREATION OF THE PERFECT SUBMUCOSAL CUSHION

The injection needle may be placed into the submucosa at the edge of a polyp. The needle should enter the mucosa almost perpendicularly and penetrate 2-3 mm behind or beside the polyp. While penetrating the needle in the submucosal plane, continuous injection will result in immediate submucosal infiltration of fluid[3,4]. Thus, gentle injection of the fluid by the assistant is recommended, as too much and too rapid injection will create a large bleb and the polyp may not rise to the desired position. The aim is to create a cushion right below the polyp. Therefore, most endoscopists begin with the injection of the substance while the needle is slowly retracted out from its deepest submucosal insertion point. Multiple repeated injections may be required to separate the mucosa and submucosal planes. In addition, if the polyp is large or flat multiple injections may be given around or into the polyp. To accomplish an adequate raise of the proximal side of the polyp, it is important to advance the scope past the lesion, i.e. orally or proximally. Another maneuver is to inject behind the polyp by performing retroflexion. The tip of the needle should only penetrate the mucosa and the upper layer of the submucosa. Thus, the needle should only approach the mucosa at a 30-degree angle and enter the base of the polyp almost tangentially to the surrounding mucosa. Entering the needle in a straight angle results in penetrating the colon wall and injection of the substance in the peritoneal cavity. The amount of in injected material will depend on the size of the polyp. If a polyp fails to elevate (Uno or “non-lifting sign”) it may be an indication of infiltration by cancer into the submucosa[31]. In this case it might be wise to mark the polyp side with a tattoo or either clips to aid the surgeon during a subsequent intra-operative localisation or at a follow up colonoscopy. The most commonly used dye for marking is India ink.

ENDOSCOPIC MUCOSAL RESECTION

EMR refers to the removal of parts or all of a mucosal lesion[3,4,6,9,32-34] (Figures 5-8). By definition, any colon polypectomy is a mucosectomy, as the main aim is to remove the entire lesion. For pedunculated polyps the in-toto resection rates are higher than for sessile or flat ones. However, EMR implies a more aggressive removal method that aims at including enough tissue below and on the surrounding borders the neoplasia (i.e., oncologic resection). The technique of submucosal cushion aims at improving the resection rates when using EMR. Although there are no studies comparing IAP with conventional polypectomy with respect to complication, it is common sense to insist that a “cushion” may result in less bleeding, perforation and possibly transmural burn syndrome. Experimental data demonstrate a benefit in the submucosal cushioning in diminishing deep tissue injury when using APC and various types of electrosurgical currents[28].

EMR USING THE PIECEMEAL-TECHNIQUE (“PIECE-MEAL POLYPECTOMY”)

There are no specific size recommendations for piecemeal polypectomy. Piecemeal polypectomy is recommended for sessile or flat polyps larger than 20 mm. When performing piecemeal polypectomy it is recommended to start at the resection at the proximal end of the polyp and to finish distally[3,4,6,9,33,34]. For very large polyps there are no set rules on how many pieces of polyp should be removed during one session. Sessile, flat or laterally spreading polyps 15 mm to 25 mm in diameter can be usually resected in two or three pieces[3,9]. We recommend to never resecting a polyp larger than 15 mm located in the cecum in one piece, unless the submucosal cushion is large enough and the separation of the deeper layers is guaranteed, i.e. the submucosal cushion is so large that it permits ensnaring the “tip of the volcano” containing all adenomatous tissue[3]. The most important aspect of the piece-meal technique is to have the mucosa well raised above the deeper layers using submucosal cushion, i.e., do not be afraid of use repeated injections until all of the polyp has been removed! In order to reduce the depth of tissue injury we recommend performing piecemeal mucosectomy using pure cut current or Endocut.

When resecting polyps with very large heads we like to decrease or shrink (i.e., vasoconstrict) the head of the polyp by injecting adrenaline solution into it. This method is called epinephrine volume reduction (EVR) or Hogan-technique[32]. By using EVR the size of the polyp head decreases making it more amenable to inspection and resection. In addition, the chances of bleeding may be diminished by using EVR[32].

Nonetheless, a complete resection of large polyps is not always possible[3,4,34]. However, application of argon plasma coagulation (APC) to the remaining tissue rests (e.g., tissue rim or small islands of adenomatous tissue) eradication rates of > 90% are achieved and the polyp recurrence is markedly reduced[9,34]. Application of APC can be done immediately after polypectomy or on follow-up[9,34]. Currents used for APC should range between 30 W (cecum) to 60 W (left colon and rectum) with flows ranging from 1-2 L/min[3,9,34]. Patients with sessile adenomas that were removed piecemeal should undergo a surveillance colonoscopy to confirm complete removal 2 mo to 6 mo after initial resection[3,4,9]. Afterwards colonoscopy should be performed every 3 mo to remove any residual neoplastic tissue until a complete endoscopic resection can be documented[9]. Once complete removal has been established, subsequent surveillance needs to be individualized based on the patient’s risk factors (e.g., metachronous polyps, family history of CRC) and endoscopist’s judgment[3,4,9].

ENDOSCOPIC SUBMUCOSAL DISSECTION

ESD is a novel technique for the resection of superficial neoplastic lesions of the gastrointestinal tract[3,4,5,35] (Figure 10). Theoretically ESD results in a high en bloc (i.e., in-toto) resection rates, but requires a high level of skill and long procedure time, sometimes up to four or five hours. The complete resection rates are about 70% to 80% in Europe whereas in Japan these reach 95%[5,35]. The use of these techniques is still limited in the cecum or in the ascending colon, except in the hands of few colonoscopists, especially from Japanese centers[5,35]. However, as ESD is time consuming and involve some risk on account of his technical features, a lesion that is resectable using polypectomy or piece-meal EMR should be treated by these conventional techniques. An absolute indication for ESD could be the need for an en-bloc resection, e.g., those lesions that require precise histological evaluation are depressed lesions and laterally spreading tumors of the non-granular type[5,35]. Other indications for ESD might be lesion with biopsy-induced scares.

The main technical difference of ESD compared to polypectomy or EMR, is the use of a distal attachment cap and the use of different knives and hemostatic devices. As expected, ESD takes also much more time[5,35]. Despite high levels of expertise, colonic ESD results in a relatively higher risk of complications (6%-14%), especially at the beginning of the learning curve and, consequently, demands a thorough knowledge, specific training and expert supervision. Although ESD has the theoretical advantage over piecemeal resection that the entire neoplastic tissue can be removed it still can’t be considered a true alternative to EMR in the Western hemisphere. Even in the Japan where colonic ESD has been performed for almost 10 years colonic ESD is still viewed as a clinical research endeavour. Nevertheless, with growing experience and training the results of ESD for selected complex colon polyps are excellent[5,35]. This has been clearly demonstrated in a recent publication by Saito et al who reported on more than 1000 successful colon ESD cases[5]. ESD is an excellent tool to remove large colon polyps in expert hands and thus represents a valuable and accepted method for difficult colon polyps.

Use of clips and endooloops

Any endoscopist performing advanced colon polypectomy should be well trained and versed using clips and loops as these methods are essential to prevent and manage complications[4,12,36]. Endoloops are mainly useful for dealing with polyps with thick stalks[36]. The endoscopist should plan to place the endoloop either before or after the resection as thick pedicles tend to contain large arteries (Figure 2). Endoloops have also been used to close colon perforations[4]. However, this is not a proven standard.

Clips are practical to close mucosal defects, obliterate a stump artery and even close perforations < 10 mm in size[4,12,37] (Figure 2D). Clips are useful to approximate the mucosal edges of a defect. There are two main types of clips: standard and 3-pronged-clip (e.g., TriClip®, Cook Medical, Winston Salem, NC, United States)[38]. Standard clips are either long- or short armed. In addition, a clip which is engineered to enable opening and closing up to five times prior o deployment (Resolution® Clip, Boston Scientific, Nattick, MA, United States) may allow for a better and more accurate repositioning before final deployment. In addition, it may grasp more tissue, resulting in a better approximation of the defect’s borders. Although some experts use clips mainly to treat complications such as bleeding and perforation, there is strong data to support its use to prevent post-polypectomy complications such as bleeding[18]. Thus, clips are useful utensils to prevent and treat some complications associated with colon polypectomy. Indeed, we recommend the use of prophylactic clips to seal the polypectomy site in patients who have even minimal abnormalities of the coagulation parameters. When suspecting perforation the use of antibiotics is mandatory[39].

LAPAROSCOPY IN THE MANAGEMENT OF DIFFICULT POLYPS

The advanced colonoscopist should always remember that there exist very efficient surgical and laparoscopic methods that allow removal of large polyps utilizing segmental or wedge resection techniques[40]. Laparoscopy is of special value for large polyps located in the transverse and right colon[40]. Laparoscopic resection is still an alternative to risky ESD or EMR procedures[40]. Conversion to an open laparotomy is only necessary in 3.2 % of the procedures. In some studies lymph node metastasis was found in 14.8% of patients, implying that most of the patients got large lesions or advanced neoplasia[3,4,36]. In addition, there is the possibility of rendezvous methods, combining colonoscopy and laparoscopy: laparoscopy assisted endoscopic resection or LAER), endoscopy-assisted laparoscopic wedge resection (EAWR), endoscopic-assisted laparoscopic translumenal resection (EATR), and endoscopic-assisted laparoscopic segment resection (EASR)[3,40].

COMPLICATIONS OF ADVANCED COLONIC POLYPECTOMY

The two most frequent complications of advanced colonic polypectomy are bleeding and perforation which range from 0.08% to 10%[3,4,9,11,37]. As mentioned above, complications associated with EMR and ESD occur more frequently than after standard polypectomy. Post-polypectomy bleeding can be immediate or delayed. In order to decrease immediate bleeding we often use prophylactic clips, endoloops and injection[36,37]. The second most common complication is perforation[11,37]. Perforation may occur during or after polypectomy or as a result of colon wall stretching while advancing the colonoscope. Perforation can occur immediately after polypectomy if a full thickness piece of colonic wall has removed and later if a necrotic patch of the colon sloughs off as a result of coagulation necrosis (“transmural burn or post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome”)[11,37]. The transmural burn syndrome is the most frequent form of “colon perforation”. Patients usually present with localized abdominal pain one or more days after polypectomy. In addition, fever may be present. On physical examination the patient has localized tenderness in the area of transmural burn. Most cases of post-polypectomy burn syndrome are “sealed-off” processes which clinically resemble appendicitis or diverticulitis. In essence, the transmural burn results in peritoneal irritation and pain. However, on occasion a sealed perforation may have ensued. In addition, a frank perforation may occur if the necrotic area expands in size and is not sealed off by the patient’s omentum. Most patients can be treated with conservative measures, including the use of broad spectrum antibiotics. However, any symptom, sign or laboratory abnormality suggesting an acute abdomen should prompt a surgical approach to repair the defect. The worst clinical scenario is the development of diffuse peritonitis and sepsis.

The most important component to prevent perforation is a good polypectomy technique (see above)[3,4]. Successful treatment of post-polypectomy perforations depends on early diagnosis, immediate use of antibiotics and rapid decision-making[37,39]. If a small perforation is seen during colonoscopy an immediate attempt at closure is warranted[37]. Although surgery has been the standard practice to manage perforations, application of clips and loops has emerged as a useful option to close lesions less than 10 mm, if these are treated as soon as detected[37,39]. In addition, immediate administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics and intravenous fluids and oxygen is mandatory[37,39]. The surgeon should also be immediately notified. The choice of antibiotics should be based on the colon flora, which includes enterobacteria such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Bacteroides fragilis and streptococci, such as Enterococcus faecalis. Thus, third-generation cepahalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone) or DNA-gyrase inhibitors (e.g., ciprofloxacin) plus an anti-bacteroides agent (i.e., metronidazole) are mandatory[39]. After colonosocopy, the development of unusual abdominal distension or delayed onset of abdominal pain warrants investigation with abdominal examination and radiography or, preferably abdominal CT. In the future novel devices such as the novel OTSC-clip may become attractive options to close larger defects of the colonic wall[41].

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Takashi Shida, MD, PhD, Department of General Surgery, Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo-ku, Chiba 260-8670, Japan; Keiichiro Kume, MD, PhD, Third Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, 1-1, Iseigaoka, Yahatanishi-ku, Kitakyusyu 807-8555, Japan; Jaekyu Sung, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, 33 Munhwa-ro, Jung-gu, Daejeon 301-721, South Korea

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor A E- Editor Yang XC

References

- 1.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Citarda F, Tomaselli G, Capocaccia R, Barcherini S, Crespi M. Efficacy in standard clinical practice of colonoscopic polypectomy in reducing colorectal cancer incidence. Gut. 2001;48:812–815. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mönkemüller K, Neumann H, Fry LC, Ivekovic H, Malfertheiner P. Polypectomy techniques for difficult colon polyps. Dig Dis. 2008;26:342–346. doi: 10.1159/000177020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mönkemüller K, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P, Fry LC. Advanced colon polypectomy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:641–652. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y, Hotta K, Sakamoto N, Ikematsu H, Fukuzawa M, Kobayashi N, Nasu J, Michida T, et al. A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Long WB, Furth EE, Ginsberg GG. Efficacy, safety, and clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection: a study of 101 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:390–396. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudo S, Lambert R, Allen JI, Fujii H, Fujii T, Kashida H, Matsuda T, Mori M, Saito H, Shimoda T, et al. Nonpolypoid neoplastic lesions of the colorectal mucosa. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:S3–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuckerman MJ, Hirota WK, Adler DG, Davila RE, Jacobson BC, Leighton JA, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Hambrick RD, Fanelli RD, et al. ASGE guideline: the management of low-molecular-weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pachlewski J, Regula J. Endoscopic mucosal rsection for colorectal polyps. Front Gastrointest Res. 2010;27:269–286. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calderwood AH, Jacobson BC. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macrae FA, Tan KG, Williams CB. Towards safer colonoscopy: a report on the complications of 5000 diagnostic or therapeutic colonoscopies. Gut. 1983;24:376–383. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.5.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jovanovic I, Milosavljevic T. Accessories used for hemostasis in gastrointestinal bleeding. Front Gastrointest Res. 2010;27:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter S, Petersen BT, Chuttani R, Croffie J, DiSario J, Liu J, Mishkin D, Shah R, Somogyi L, Tierney W, et al. Polypectomy devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:741–749. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuttani R, Barkun A, Carpenter S, Chotiprasidhi P, Ginsberg GG, Hussain N, Liu J, Silverman W, Taitelbaum G, Petersen B. Endoscopic clip application devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waye JD, Atchison MA, Talbott MC, Lewis BS. Transillumination of light in the right lower quadrant during total colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:69. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waye JD. It ain’t over ‘til it’s over: retrieval of polyps after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:257–259. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fry LC, Lazenby AJ, Mikolaenko I, Barranco B, Rickes S, Mönkemüller K. Diagnostic quality of: polyps resected by snare polypectomy: does the type of electrosurgical current used matter? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2123–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parra-Blanco A, Kaminaga N, Kojima T, Endo Y, Tajiri A, Fujita R. Colonoscopic polypectomy with cutting current: is it safe? Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:676–681. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.105203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mönkemüller KE, Fry LC, Jones BH, Wells C, Mikolaenko I, Eloubeidi M. Histological quality of polyps resected using the cold versus hot biopsy technique. Endoscopy. 2004;36:432–436. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Zimmermann L, Mania A, Zabielski M, Jovanovic I. Advanced endoscopic imaging methods for colon neoplasia. Dig Dis. 2010;28:629–640. doi: 10.1159/000320065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Togashi K, Osawa H, Koinuma K, Hayashi Y, Miyata T, Sunada K, Nokubi M, Horie H, Yamamoto H. A comparison of conventional endoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and the optimal-band imaging system for the differentiation of neoplastic and non-neoplastic colonic polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teixeira CR, Torresini RS, Canali C, Figueiredo LF, Mucenic M, Pereira Lima JC, Carballo MT, Saul C, Toneloto EB. Endoscopic classification of the capillary-vessel pattern of colorectal lesions by spectral estimation technology and magnifying zoom imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:750–756. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan C, Pickhardt PJ, Rex DK. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:865–89, 865-89. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uren NG, Camici PG. Hibernation and myocardial ischemia: clinical detection by positron emission tomography. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1992;6:273–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00051150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fry LC, Loudon R, Linder JD, Mönkemüller KE. Endoscopic removal of a snare entrapped around a polyp by using a dual endoscope technique and needle-knife. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:126–128. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamlet R, Carr KE, Toner PG, Nias AH. Scanning electron microscopy of mouse intestinal mucosa after cobalt 60 and D-T neutron irradiation. Br J Radiol. 1976;49:624–629. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-49-583-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shershnev VG, Zubarev VV. [Effect of nitroglycerin and platyphilline on hemodynamics in patients with coronary insufficiency caused by arteriosclerosis] Vrach Delo. 1975;89:10–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norton ID, Wang L, Levine SA, Burgart LJ, Hofmeister EK, Rumalla A, Gostout CJ, Petersen BT. Efficacy of colonic submucosal saline solution injection for the reduction of iatrogenic thermal injury. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:95–99. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varadarajulu S, Tamhane A, Slaughter RL. Evaluation of dextrose 50 % as a medium for injection-assisted polypectomy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:907–912. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kashimura K, Mizushima Y, Oka M, Enomoto S, Kakushima N, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Iguchi M, et al. Comparison of various submucosal injection solutions for maintaining mucosal elevation during endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2004;36:579–583. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uno Y, Munakata A. The non-lifting sign of invasive colon cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:485–489. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogan RB, Hogan RB. Epinephrine volume reduction of giant colon polyps facilitates endoscopic assessment and removal. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1018–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.How good are knee replacements? Lancet. 1991;338:477–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regula J, Wronska E, Polkowski M, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Pachlewski J, Rupinski M, Butruk E. Argon plasma coagulation after piecemeal polypectomy of sessile colorectal adenomas: long-term follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2003;35:212–218. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto H, Yahagi N, Oyama T. Mucosectomy in the colon with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2005;37:764–768. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Giorgio P, De Luca L, Calcagno G, Rivellini G, Mandato M, De Luca B. Detachable snare versus epinephrine injection in the prevention of postpolypectomy bleeding: a randomized and controlled study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:860–863. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jovanovic I, Zimmermann L, Fry LC, Mönkemüller K. Feasibility of endoscopic closure of an iatrogenic colon perforation occurring during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominitz JA, Eisen GM, Baron TH, Goldstein JL, Hirota WK, Jacobson BC, Johanson JF, Leighton JA, Mallery JS, Raddawi HM, et al. Complications of colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:441–445. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mnkemller K, Akbar Q, Fry LC. Use of antibiotics in therapeutic endoscopy. Front Gastrointest Res. 2010;27:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benedix F, Köckerling F, Lippert H, Scheidbach H. Laparoscopic resection for endoscopically unresectable colorectal polyps: analysis of 525 patients. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2576–2582. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teoh AY, Chiu PW, Ng EK. Current developments in natural orifices transluminal endoscopic surgery: an evidence-based review. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4792–4799. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i38.4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]