Abstract

We report studies of the effect of ischemia on the metabolic activity of the intact, perfused lung, and its restoration after a period of reperfusion. Two groups of rat lungs were studied using hyperpolarized 1-13C pyruvate to compare the rate of lactate labeling, differing only in the temporal ordering of ischemic and normoxic acquisitions. In both cases, a several-fold increase in lactate labeling was observed immediately after a 25-minute ischemia event as was its reversal back to the baseline after 30–40 minutes of resumed perfusion (n=5, p < 0.025 for both comparisons). These results were corroborated by 31P spectroscopy, and correspond well to measured changes in lactate pool size determined by 1H spectroscopy of freeze-clamped specimens.

Keywords: Hyperpolarization, lung metabolism, multinuclear MRI

Introduction

The lung presents inherent challenges to investigation by NMR. Low tissue density results in low signal density, and the magnetic susceptibility discontinuity at air-tissue interfaces produces a great deal of line-broadening. Consequently, very few lung NMR studies have been reported, and these have been limited to 31P investigations of the isolated, perfused rat lung (1,2) and the perfused pig lung (3,4). To our knowledge, 13C NMR studies have only been performed on lung tissue specimens (5) and extracts (6); we present here the first use of hyperpolarized 13C NMR spectroscopy to observe metabolism in the intact lung. The advent of fast-dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) has allowed real-time observation of metabolism by increasing the signal-to-noise ratio of 13C-labeled metabolites by four orders of magnitude (7), and we have used this method to combat the characteristic problems of spectroscopy in the lung.

Due to its excellent polarization characteristics and rapid inclusion in important metabolic cycles, metabolic studies using pyruvate constitute the bulk of the hyperpolarized 13C work performed to date. Of particular interest is the reversible conversion of pyruvate to lactate, rapidly catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The evolution of the [1-13C]lactate signal observed after injection of [1-13C]pyruvate arises from a combination of longitudinal relaxation, net metabolic flux, and label exchange between the pyruvate and lactate pools; the latter two processes are mediated by LDH. Recent work, however, points to the primary importance of label exchange in modeling experimental results (8) over the time course of a typical hyperpolarized pyruvate experiment. Qualitatively, as the lactate pool size increases, so does the signal corresponding to hyperpolarized lactate, as an accumulation of lactate provides a greater pool of exchange for the 13C label. This exchange has been commonly modeled in vivo (9) and in vitro (10) with a dual-site model, and the increases in both lactate signal and in the apparent exchange rate constants (corresponding to increased lactate pool size and increased LDH expression, respectively) have been found in various tumor models (9,11,12), including non-small cell lung cancer (13).

In addition to indicating the presence of the Warburg effect in tumors, the conversion of pyruvate to lactate yields information about the oxidative state of tissue. In an ischemic state, the accumulation of lactate from fermentative glycolysis causes an increase in the observed lactate signal, and this has been previously demonstrated in the Langendorff heart (14,15). We have now observed a similar effect with [1-13C]pyruvate in the isolated perfused rat lung. Changes in the oxidative state of the lung are integral to ischemia-reperfusion injury, a serious problem encountered in lung transplantation, and retention of aerobic metabolism during storage is highly beneficial (16). In combination with 31P-NMR spectroscopy, 13C spectroscopy of hyperpolarized pyruvate not only provides a method to non-destructively probe the state of oxidative phosphorylation in lung tissue, but it also offers the potential to acquire regional information via imaging techniques.

Materials and Methods

General animal handling

All animal experiments were performed under an IACUC-approved protocol at the University of Pennsylvania. Ten male Sprague-Dawley rats (300–450 g) were utilized in this study. The subjects were anesthetized with i.p. pentobarbital, tracheostomy was performed, and 200 U heparin were administered via tail vein to prevent alterations in lung perfusion due to clotting. The lungs were prepared for NMR study according to the previously reported method of “degassing” (1,3). That is, the animals were ventilated with pure O2 (50 bpm, 11–14 cm H2O PIP) for 10 minutes in order to remove all N2 from the airways. After ventilation, the trachea was sealed (end exhalation) with a suture, allowing residual O2 to be absorbed by the circulating blood and perfusate. Thoracotomy was quickly started, the heart was cut transversely, and the pulmonary artery was cannulated via the right ventricle. After perfusion was started, the lungs were rapidly excised and placed in a 20-mm NMR tube. The lungs were perfused at 14.6 mL/min with a modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer: 119 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3−, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 4.7 mM KCl, 10 mM glucose, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA). The perfusate was passed through an oxygenating column under a constant flow of 1 atm 95:5 O2/CO2, and warmed via passage through water-jacketed tubing.

Hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate injection

37 mg [1-13C]pyruvic acid (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) were polarized to ~30% at 1.42 K and 94 GHz with a HyperSense DNP system (Oxford Instruments). Before insertion into the DNP system, the neat pyruvic acid was mixed with 1.7% by weight OX063 trityl radical (Oxford Instruments) and Dotarem™ Gd chelate (Guerbet) was added to achieve a total concentration of 15 mmol per mole pyruvate. 4.5 mL Tris-buffered saline was heated to 190°C at 10 bar, and was used to rapidly dissolve the frozen sample. This solution was diluted in 12.5 mL oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit buffer, yielding a neutral, isotonic solution of 24 mM [1-13C]pyruvate. This solution was injected into the perfusate line at 14.6 mL/min in lieu of the steady-state perfusion buffer. The relaxation of the hyperpolarized agent was slightly affected by the use of a power injector; we estimated the T1 in the syringe during the injection to be approximately 35 seconds.

Ischemia study design

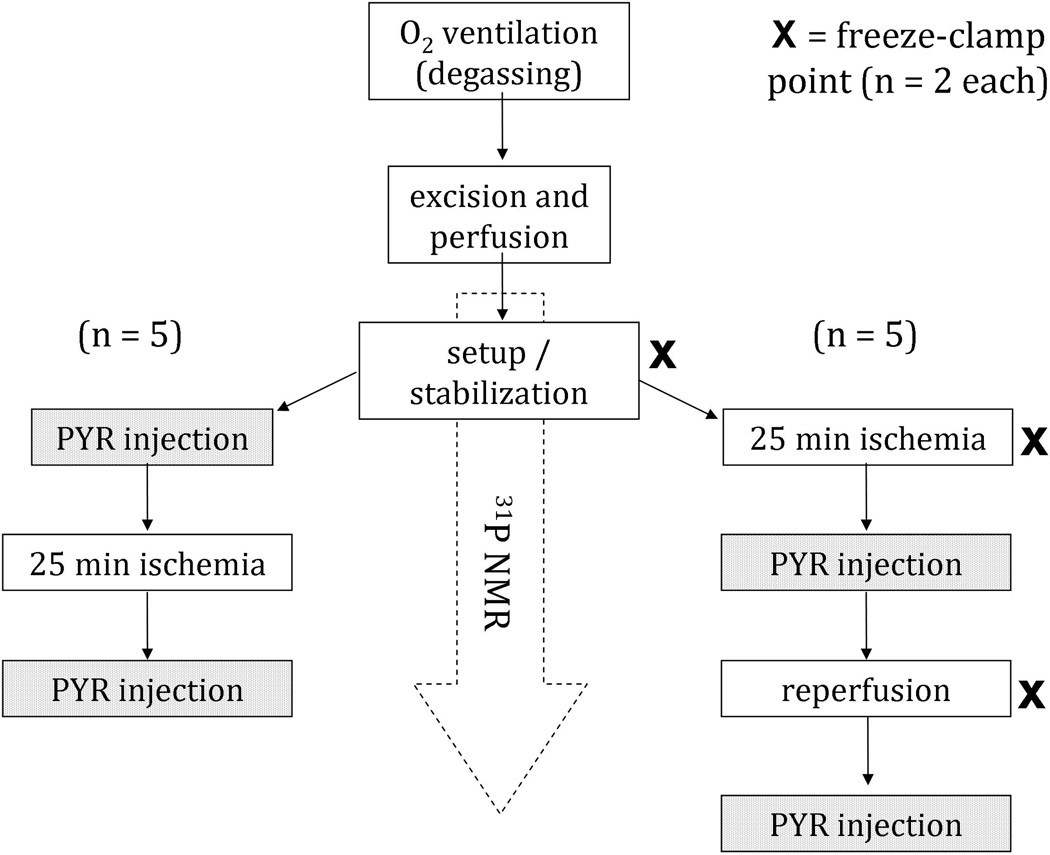

Metabolism of hyperpolarized pyruvate was observed under two conditions: normoxic and ischemic. Global ischemia was accomplished by stopping the flow of perfusate for 25 min. Both conditions were tested in each lung, but in reverse order. In one set of lungs, hyperpolarized pyruvate was first injected under normoxic conditions, and an hour later, hyperpolarized pyruvate was injected after 25 min of ischemia. In the other set, the first injection was performed after 25 min of ischemia, and the lung was immediately reperfused after injection. After an hour of reperfusion, hyperpolarized pyruvate was injected a second time. 31P spectra were collected before ischemia, during ischemia, and during reperfusion to confirm the expected metabolic changes according to each state. The flow chart of Figure 1 provides additional clarification. After completion of two of the studies, perfusion was halted for at least three hours, after which an additional hyperpolarized pyruvate sample was infused, to confirm that no additional peaks were seen in ‘dead’ lung tissue when compared to the hyperpolarized sample alone.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the experimental groups of this study. Hyperpolarized 1-13C pyruvate was administered to ten sets of lungs immediately post-ischemia as well as under normoxic conditions. In half of the cases, the normoxic condition was studied pre-ischemia (left) and in the other half normoxia was achieved through post-ischemia reperfusion (right).

PCA Extracts

Six additional lungs were perfused in order to study the tissue extracts with high-resolution 31P and 1H NMR spectroscopy. Two lungs were freeze-clamped after 45 min of normoxic perfusion (corresponding to the time point at which we had previously injected pyruvate), two immediately after 25 min of stopped-flow ischemia, and two after ischemia followed by 80 min of reperfusion. The entire lung block (~2 g frozen) was freeze-clamped and extracted into ice-cold perchloric acid. After neutralization to pH = 7.2±0.2, the extracts were kept at −85°C until they were lyophilized, redissolved in D2O, and analyzed in a 9.4 T spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). Spectra were acquired under non-saturating conditions (repetition time ≫ T1) to allow quantitative interpretation, and 1H decoupling was employed during only the 31P acquisition and not during the inter-scan relaxation time. After 1H acquisition, EDTA was added (50 mM final concentration) and the pH was raised to 8.0±0.1 for 31P acquisition. Metabolites were quantified by peak integrals, which were normalized to total frozen weight.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR spectroscopy on perfused lungs was performed with a 20-mm 1H-X probe (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) on a wide-bore 9.4-T vertical magnet. 31P spectra were acquired throughout the course of the experiment with the following parameters: flip angle = 75°, repetition time = 1 s, 512 scans, acquisition time = 8.5 min, spectral window = 39 kHz. Peak amplitudes were determined by fitting the spectral peaks to Lorentzians in a custom MatLab (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) routine. Individual 13C spectra were acquired with a 2-s repetition time. The scans were acquired with a nominal 45° flip angle (calibrated once for typical sample loading) and 24.5-kHz spectral window, and were analyzed with SpinWorks NMR software (University of Manitoba). In order to separate the lactate peak from a nearby impurity, peak area was calculated by fitting two nearby Lorentzian peaks to the lactate region and discarding that which corresponded to the lower chemical shift (note that the impurity peak, but not the lactate peak, was detectable in control phantom and dead lung experiments and did not change substantially among phantom, normoxic, ischemic, and dead lung experiments).

Results

13C Spectroscopy

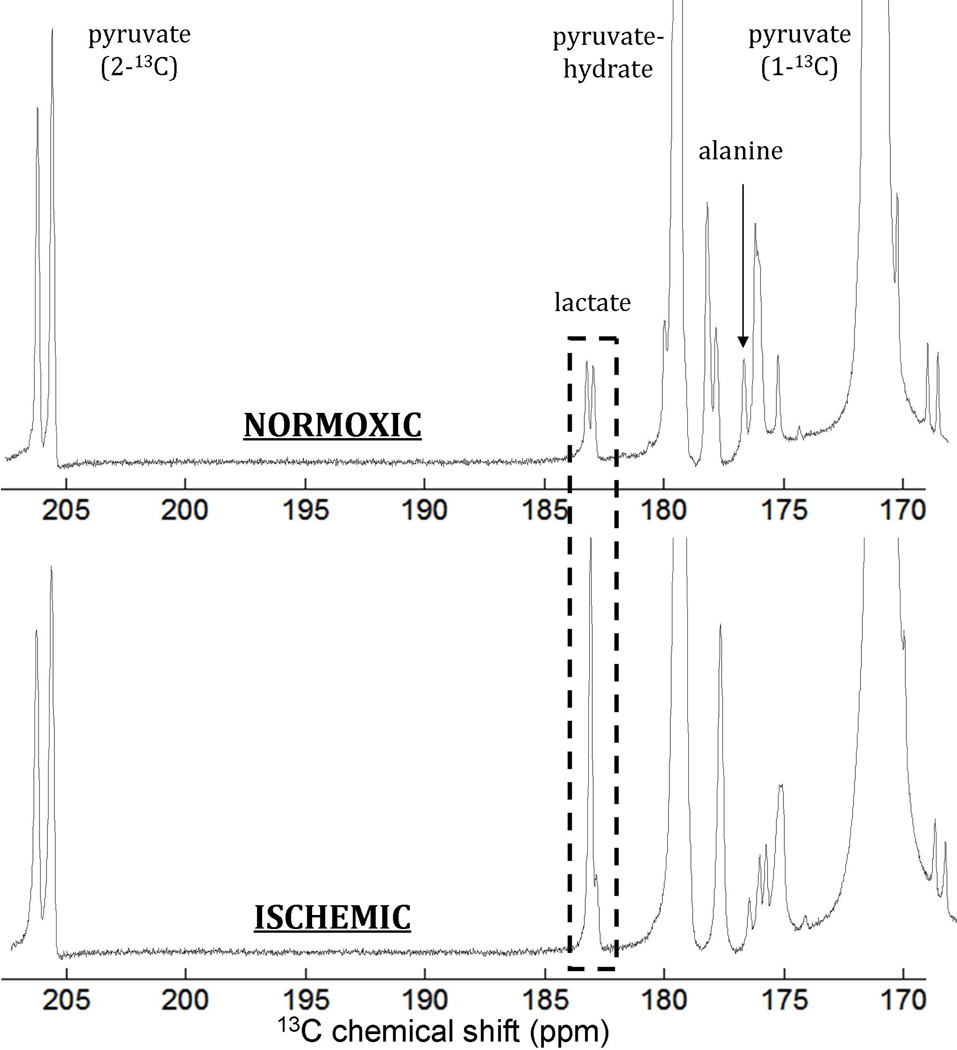

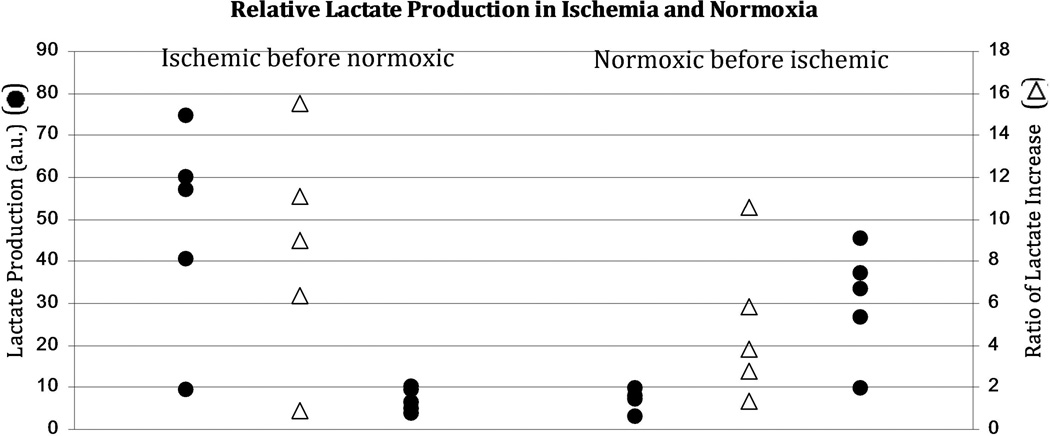

Representative spectra are shown in Figure 2. Lactate “signal” was parameterized by normalizing the maximum lactate peak area to the maximum pyruvate peak area over the spectral time course. This method has been previously used to quantify production of hyperpolarized labeled metabolites (17). In addition to comparing the absolute lactate production in ischemic and normoxic states, we compared the relative increase (ratio) in lactate signal in the ischemic state with respect to lactate signal in the normoxic state (Figure 3 and Table 1). The increase in lactate signal for the post-ischemic injection was highly significant for both cohorts. When ischemic injection preceded normoxic injection, the lactate signal decreased from 48±25 to 6.9±2.9 (α=0.05, p=0.025); when ischemic injection followed normoxic injection, the lactate signal increased from 7.5±2.7 to 31±14 (α=0.05, p=0.01). Moreover, although the former group showed a higher average ratio of increase in lactate signal (8.6±5.4 vs 4.9±3.6), the means were not statistically different for a two-tailed T-test. Both groups contained a single outlier, in which lactate signal from both injections resembled that of a typical normoxic injection. We do not know the reason that these two tests were qualitatively different, or of any justification for rejecting these outliers. They were therefore included in all analysis.

Figure 2.

Representative spectra comparing the normoxic perfused lung (top) with the post-ischemic lung (bottom). As with all spectra in this study, these show similar overall signal-to-noise and differ primarily in the amount of lactate observed (dashed box). Note that the rightmost line in the apparent doublet corresponding to lactate is seen in the absence of the lung as well, indicating that it corresponds to an impurity in the pyruvate itself. No change is seen in this line with ischemia. All of the other unlabeled peaks are similarly impurities (visible with or without perfused tissue present). We do not know the identity of these impurities.

Figure 3.

A comparison of the hyperpolarized lactate label produced by ischemic (outermost black circles) and normoxic (innermost black circles) lungs. Note the substantial increase in both lactate labeling and variability post-ischemia depending on the order of the acquisitions (ischemic first, left, and normoxic first, right). Reperfusion essentially reduces the lactate labeling rate to its pre-ischemic condition. Post-ischemic measurements are characterized by both an increased lactate labeling rate and an increased variability between trials. The ratios of lactate labeling in post-ischemic trials to that of the corresponding normoxic trials appear as unfilled triangles. Note that although a large and recoverable lactate increase post-ischemia was typical, two trials, one from each temporal ordering, showed minimal or no increase in the lactate peak post-ischemia.

Table 1.

A comparison of lactate labeling under post-ischemic and normoxic conditions in both study groups. Lactate labeling is increased to a statistically significant degree post-ischemia, and is statistically indistinguishable from pre-ischemia after reperfusion.

| Lactate Production | Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic | → | Normoxic | |

| 48 ± 25 | 6.9 ± 2.9 |

8.6 ± 5.4 |

|

| α = 0.025 | |||

| Normoxic | → | Ischemic | |

| 7.5 ± 2.7 | 31 ± 14 |

4.9 ± 3.6 |

|

| α = 0.01 | |||

31P Spectroscopy

A representative series of spectra are shown in Figure 4. In all spectra, peaks corresponding to the following metabolites were clearly observed, listed from downfield to upfield: phosphomonoesters (PMEs), inorganic phosphate (Pi), phosphodiesters (PDEs), phosphocreatine (PCr), γ-ATP, α-ATP, NAD+/NADH, and β-ATP. Within 10 minutes of ischemia onset, significant reduction in peak amplitude was observed for PCr and all of the ATP peaks (Table 2). Within 30–40 minutes of reperfusion, the peaks recovered to a fraction of their original amplitudes. In two of the lungs, both from the ischemic before normoxic sequence, PCr dropped below the detection limit during ischemia, and were accordingly excluded from the calculation of PCr decrease. Table 2 displays the average changes in peak amplitudes for PCr and β-ATP. No significant differences were observed between the two experimental groups (normoxic before ischemic or ischemic before normoxic). Spectra could not be acquired sooner than 10 minutes after the injection, but no changes from the initial 13C agent injection were exhibited in the 31P spectra.

Figure 4.

A representative series of 31P spectra over the course of ischemia and reperfusion. As in all of the trials, the most perceptible changes due to ischemia are in PCr and α-ATP levels. Spectra are referenced to PCr at 0 ppm.

Table 2.

Intensities of 31P metabolite peaks after 10 min ischemia and 30–40 min reperfusion. Intensities are reported as fractions of pre-ischemia intensity. Both PCr and β-ATP levels are reduced after ischemia, and are largely restored after reperfusion. In each case, the normoxic and ischemic distributions are significantly different, as judged by the two-sample T-test at the 5% significance level (p < 0.02 in all cases).

| PCr | β-ATP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Ischemia | Reperfusion | Ischemia | Reperfusion |

|

Ischemic→ Normoxic |

0.34 ± 0.12 | 0.89 ± 0.23 | 0.55 ± 0.11 | 0.81 ± 0.16 |

|

Normoxic→ Ischemic |

0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.18 | 0.55 ± 0.11 | 0.75 ± 0.18 |

PCA Extracts

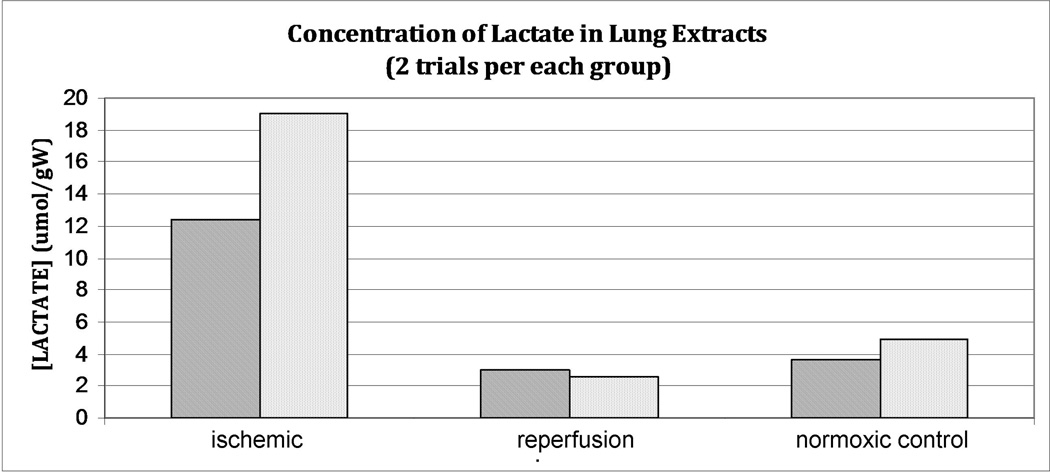

A prominent lactate signal was observed in the 1H extract spectra. Comparison with a proton standard capillary allowed us to calculate the tissue concentration of lactate, which was observed to increase markedly (Figure 5) during ischemia and return near to the pre-ischemia baseline after reperfusion of a duration identical to that used in the hyperpolarized pyruvate experiments. The average lactate increase observed post-ischemia (a factor of ~4.5) approximates that of the hyperpolarized lactate signal increase under identical conditions.

Figure 5.

Lactate concentrations measured in lung extracts of freeze-clamped lungs immediately post-ischemia (left), after ischemia/reperfusion (center) and in control lungs which were not subjected to ischemia (right). Because only two animals were sacrificed for each study, statistical significance was not established. Nonetheless, a T-test analysis distinguishes ischemic from normoxic lactate concentrations at the 10% significance level (α=0.05, p<0.08 in both cases).

Discussion and Conclusion

31P spectroscopy corroborated the metabolic changes observed during the onset of ischemia and reperfusion. Reduction and recovery of PCr and ATP are observed during ischemia-reperfusion of various tissues, and more specifically have been observed during normothermic ischemia-reperfusion in lungs of rats1, pigs3, and rabbits (18). β-ATP is an especially good metric for comparison with data from other studies. Unlike the other ATP peaks, it does not overlap with an analogous phosphate resonance from ADP. Moreover, it is more isolated than the other ATP peaks from the broad baseline often observed in 31P spectra, and its quantification is therefore more reliable. Although the observed decrease in β-ATP intensity is less than that observed by Hayashi et al. (1) (30% vs. 55% of original signal intensity), the duration of ischemia at the evaluated time point was shorter in our experiments. The lungs were subjected to 25 total minutes of stopped flow, but requisite hardware preparations for 13C spectroscopy precluded 31P acquisitions later in ischemia.

Unlike in 31P spectroscopy, where NMR signal is directly correlated with endogenous pools of metabolites, lactate signal in hyperpolarized 13C spectroscopy is a more complicated combination of factors. As observed in the PCA extracts, the increased hyperpolarized lactate signal does correlate with a comparable increase in endogenous lactate concentration, fitting with the label exchange models proposed in other previous research (8). However, this does not provide an exact account of hyperpolarized lactate signal. Firstly, it is dependent on the polarization level of the metabolic precursor pyruvate, which can vary from one experiment to another. We addressed this issue by expressing lactate production as a value normalized to the maximum pyruvate signal. Secondly, lactate metabolism is initially dependent upon transport of pyruvate to the parenchyma, and perfusion may vary from one lung to another. Additionally, we were concerned that pyruvate delivery may be a function of injection sequence. That is, increased microvascular leakage (19) and edema (20) are common manifestations of ischemia-reperfusion injury, and could affect lactate signal by virtue of changing pyruvate movement across the capillary and interstitial fluid and the concentration therein. These complications cannot be accounted for by normalization to the pyruvate signal. Much of the injected hyperpolarized pyruvate is not taken up by the lung, and exits into the perfusate bath in the NMR tube, where it continues to contribute to the NMR signal. Pyruvate signal intensity is therefore not an accurate indicator of pyruvate delivery. We accounted for these problems by performing two injections on each set of lungs (to avoid perfusion differences due to anatomy or surgical preparation), and by performing half of the experiments with a pyruvate injection after ischemia-reperfusion and half with an injection prior (to correct for confounding factors due to damage by ischemia-reperfusion).

It is instructive to discuss possible explanations for the outlier in each experimental group. In both cases, anomalously low lactate signal was observed during post-ischemic injection. As discussed above, the production of lactate signal is affected by pyruvate delivery. For the case in which the ischemic injection came second, the lung had been exposed to an extended period of perfusion, and would have consequently grown edemic. Diffusion across the interstitial fluid would have therefore been slowed, and rising arterial pressure could have resulted in leakage prior to the capillary bed. For the case in which ischemic injection came early, a different explanation is more likely. It has been previously found that alveolar oxygen can sufficiently sustain oxidative metabolism in a lung subjected to normoxic ischemia: De Leyn et al. found that rabbit lungs inflated with air or O2 did not exhibit a significant increase of lactate until 6- and 20-fold (respectively) the duration of ischemia required to produce the same change in deflated lungs (21). In our experiments, we found that despite ligating the trachea at end-exhalation, some lungs contained small regions of inflation which would collapse over the course of the experiment. It is possible that this residual oxygen could protect regions of the ischemic lung from entering fermentative metabolism. Furthermore, hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction would tend to redirect perfusate flow to the least hypoxic pulmonary tissues. However, De Leyn et al. reported that changes in lactate and ATP followed nearly identical timescales, and in the case of both outliers, the reduction of β-ATP (45 and 55% of original) was comparable to the group average. Similarly, reperfusion in both outliers yielded an average recovery of ATP and PCr, so a loss of tissue viability is not a likely explanation.

It is notable that the overall level of metabolites seen in this study is substantially less than has been observed in most situations in solid organs, owing to the overall lower tissue density and modest metabolic activity of the lung. Nonetheless, the metabolite signal is sufficient to allow for accurate quantification of the spectra. Except in as far as they affect this quantification, we do not believe that the presence of impurities affects the results described here, in that they are equally present in all experiments, and their apparent concentration is approximately at the 0.1% level or below. While the relatively low signal level corresponding to metabolism in the lung may make true in vivo imaging of hyperpolarized metabolites in the healthy organ difficult, it is also notable that this low metabolic activity may provide higher contrast when distinguishing tissue of higher density and/or metabolic activity, e.g., lung tumors. This study provides a basis for exploring the extent to which metabolically active tumor issue might be confused with localized ischemia when pursuing such an application.

This study marks the first use of hyperpolarized 13C NMR to study the intact lung. We have demonstrated that hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate can be used to detect the reversible changes in intracellular lactate during ischemia and reperfusion. Signal increases were highly significant, typically 5- to 10-fold or more. Hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate spectroscopy therefore provides a complement to 31P spectroscopy as a rapid, non-destructive method of assessing the metabolic state of the lung.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Dr. Suzanne Wehrli for acquiring the spectra extracts, and David Nelson for his extensive assistance in teaching us the PCA extract protocol.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant #R01-EB010208

Abbreviations used

- DNP

Dynamic Nuclear Polarization

- LDH

Lactate Dehydrogenase

- PIP

Peak Inspiration Pressure

- PCA

Perchloric acid

References

- 1.Hayashi Y, Inubushi T, Nioka S, Forster RE. 31P-NMR spectroscopy of isolated perfused rat lung. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74(4):1549–1554. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hexem JG, Marshall C, Marshall BE, DiVerdi JA, Opella SJ. Proceedings of the Int Soc for Magn Reson in Med. New York, New York: 1984. 31P NMR Studies of Isolated Perfused Atelectatic Rat Lung. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillai RP, Buescher PC, Pearse DB, Sylvester JT, Eichhorn GL. 31P NMR spectroscopy of isolated perfused lungs. Magn Reson Med. 1986;3(3):467–472. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buescher PC, Pearse DB, Pillai RP, Litt MC, Mitchell MC, Sylvester JT. Energy state and vasomotor tone in hypoxic pig lungs. J. Appl. Physiol. 1991;70(4):1874–1881. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halliday KR, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Sillerud LO. Differentiation of human tumors from malignant tissue by natural-abundance 13C NMR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1988;7(4):384–411. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer PE, Jessen ME, Patel JB, Chao RY, Malloy CR, Meyer DM. Effects of storage and reperfusion oxygen content on substrate metabolism in the isolated rat lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70(1):264–269. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01538-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. PNAS. 2003;100(18):10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kettunen MI, Hu DE, Witney TH, McLaughlin R, Gallagher FA, Bohndiek SE, Day SE, Brindle KM. Magnetization transfer measurements of exchange between hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate and [1-13C]lactate in a murine lymphoma. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(4):872–880. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day SE, Kettunen MI, Gallagher FA, Hu DE, Lerche M, Wolber J, Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Brindle KM. Detecting tumor response to treatment using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Nat Med. 2007;13(11):1382–1387. doi: 10.1038/nm1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris T, Eliyahu G, Frydman L, Degani H. Kinetics of hyperpolarized 13C1-pyruvate transport and metabolism in living human breast cancer cells. PNAS. 2009;106(43):18131–18136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909049106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohndiek SE, Kettunen MI, Hu DE, Witney TH, Kennedy BW, Gallagher FA, Brindle KM. Detection of tumor response to a vascular disrupting agent by hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(12):3278–3288. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson PE, Bok R, Kerr AB, Lustig M, Hu S, Chen AP, Nelson SJ, Pauly JM, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB. Investigation of tumor hyperpolarized [1-13C]-pyruvate dynamics using time-resolved multiband RF excitation echo-planar MRSI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(3):582–591. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seth P, Grant A, Tang J, Vinogradov E, Wang X, Lenkinski R, Sukhatme VP. On-target inhibition of tumor fermentative glycolysis as visualized by hyperpolarized pyruvate. Neoplasia. 2011;13(1):60–71. doi: 10.1593/neo.101020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder MA, Atherton HJ, Ball DR, Cole MA, Heather LC, Griffin JL, Clarke K, Radda GK, Tyler DJ. Real-time assessment of Krebs cycle metabolism using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. FASEB J. 2009;23(8):2529–2538. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Storey C, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Inhibition of carbohydrate oxidation during the first minute of reperfusion after brief ischemia: NMR detection of hyperpolarized 13CO2 and H13CO3−. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Perrot M, Liu M, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S. Ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(4):490–511. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-670SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder MA, Cochlin LE, Heather LC, Clarke K, Radda GK, Tyler DJ. In vivo assessment of pyruvate dehydrogenase flux in the heart using hyperpolarized carbon-13 magnetic resonance. PNAS. 2008;105(33):12051–12056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805953105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall TS, Buescher PC, Borkon AM, Reitz BA, Michael JR, Baumgartner WA. 31P nuclear magnetic resonance determination of changes in energy state in lung preservation. Circulation. 1988;78(5 Pt 2):III95–III98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eppinger MJ, Deeb GM, Bolling SF, Ward PA. Mediators of ischemia-reperfusion injury of rat lung. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(5):1773–1784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Perrot M, Liu M, Waddell TK, Keshavjee Shaf. Ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:490–511. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-670SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Leyn PR, Lerut TE, Schreinemakers HH, Van Raemdonck DE, Mubagwa K, Flameng W. Effect of inflation on adenosine triphosphate catabolism and lactate production during normothermic lung ischemia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55(5):1073–1078. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90010-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]