Abstract

In cells exposed to environmental stress, inhibition of translation initiation conserves energy for the repair of cellular damage. Untranslated mRNAs that accumulate in these cells move to discrete cytoplasmic foci known as stress granules (SGs). The assembly of SGs helps cells to survive under adverse environmental conditions. We have analyzed the mechanism by which hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced oxidative stress inhibits translation initiation and induces SG assembly in mammalian cells. Our data indicate that H2O2 inhibits translation and induces the assembly of SGs. The assembly of H2O2-induced SGs is independent of the phosphorylation of eIF2α, a major trigger of SG assembly, but requires remodeling of the cap-binding eIF4F complex. Moreover, H2O2-induced SGs are compositionally distinct from canonical SGs, and targeted knockdown of eIF4E, a protein required for canonical translation initiation, inhibits H2O2-induced SG assembly. Our data reveal new aspects of translational regulation induced by oxidative insults.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, RNA, stress granules, translation

1. Introduction

Translational repression triggered by stress occurs as a consequence of reduced translation initiation. This results from reduced assembly of the pre-initiation complexes eIF4F (composed of eIF4E, eIF4G, and eIF4A) and 43S (composed of the small ribosomal subunit in association with several initiation factors) [1]. Assembly of the eIF4F complex is inhibited by eIF4E-binding proteins (4EBPs) that interfere with interactions between eIF4E and eIF4G [2]. Stress-induced inactivation of the PI3K-mTOR pathway reduces the constitutive phosphorylation of 4EBPs to promote the assembly of inhibitory eIF4E:4EBP complexes [2]. Assembly of the 43S complex is inhibited by stress-induced activation of PKR, PERK, GCN2 and HRI, kinases that phosphorylate eIF2α, a component of the eIF2-GTP-tRNAMet ternary complex essential for 43S assembly [1]. These complementary mechanisms are primarily responsible for the global repression of protein synthesis observed in cells subject to adverse environmental conditions.

Non-translatable mRNAs that accumulate as a result of stress-induced translational repression are frequently compartmentalized into cytoplasmic foci known as stress granules (SGs) [3; 4]. SGs are ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes composed of abortive translation initiation complexes and a host of RNA binding proteins and signaling proteins involved in various aspects of cellular metabolism. Current evidence suggests that SGs, in concert with a related class of RNA granule known as the processing (P-) body, play important roles in determining the fate of mRNAs in stressed cells [5]. SGs have also been implicated in stress-induced signaling cascades such as inflammatory signaling and stress-induced apoptotic signaling [6; 7]. Thus, SGs are thought to promote cell survival under stress conditions by modulating various aspects of cell metabolism.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are an important trigger for SG assembly. However, whether hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), the most common and stable form of ROS, induces SG assembly has remained controversial. Whereas some studies report that H2O2 induces SG assembly [8; 9; 10], others do not [6; 7; 11]. When H2O2-induced SGs were observed, they were rapidly disassembled, suggesting that their composition may be different than canonical SGs induced by other stimuli. In the present study, we found that both the mechanism of H2O2-induced SG assembly and the composition of H2O2-induced SGs are different than that of canonical SGs. We show that H2O2 triggers phospho-eIF2α-independent SG assembly by disrupting the eIF4F complex. Unlike phospho-eIF2α-triggered SGs, H2O2-induced SGs often lack eIF3b, a key component of the translation initiation machinery. Our results reveal that H2O2 triggers a novel class of SGs that may have unique properties in the regulation of the stress response program.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture and drug treatment

U2OS cells, wild type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) as well as MEFs expressing mutant eIF2α (S51A) were cultured as described previously [12]. Treatment of cells with sodium arsenite (Sigma), pateamine A (Desmethyldesamino-modified; a gift from Jun Liu, Johns Hopkins University) or emetine (Sigma) was as described in [13]. For H2O2 (Sigma) treatment, cells were incubated with the indicated H2O2 concentrations in normal growth medium at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 1 or 2 hr. N-acetyl Cysteine (NAC) treatment was done as previously described [14].

2.2. Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibodies to G3BP, HuR, p70 S6 kinase (SK1-hedls), eIF4E, 4E-BP1, 4E-T and PABP, rabbit polyclonal antibody to eIF4G, goat polyclonal antibodies to eIF3b, TIAR, TIA-1, or FXR1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit polyclonal phospho-specific anti-eIF2α was from Assay Designs, rabbit polyclonal anti-RCK was from Bethyl, mouse monoclonal anti-HA was from Covance and mouse monoclonal antibody to β-actin was from Chemicon. Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were from GE Healthcare. Cy2-, Cy3-, and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Labs.

2.3. DNA plasmids, siRNAs, and cell transfection

Plasmids pMT2-HA, which expresses either wild type eIF2α or a non-phosphorylatable eIF2α S51A mutant were described previously [15]. Control siRNA (D0) was designed as described previously [16]. siGENOME SMART pool siRNA for HRI [17] and eIF4E were purchased from Thermo Scientific. 4E-BP1 siRNA (5′TGGGAACTCACCTGTGACCAA3′) was purchased from Qiagen. Transfections with DNA plasmids or siRNAs were done as previously described [12].

2.4. Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblotting was done as described previously [12]. Briefly, cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (5 mM MES (Sigma) pH 6.2 and 2% SDS), and equal amounts of protein were separated by 4–20% SDS-PAGE before transfer to nitrocellulose filter membranes. After 1hr of blocking in 5% normal horse serum (NHS) in TBS, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies and proteins were detected using the Super Signal chemiluminescent detection system (Pierce).

2.5. 7-Methyl GTP Sepharose Chromatography

Assembly of eIF4E-containing complexes from untreated U2OS cell lysates or lysates treated with H2O2 (1 mM, 2 hours) or SA (100 μM, 2hours) was performed as described [18].

2.6. Immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunofluorescence was done as previously described [11; 13]. Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde, permeabilized using 100% chilled methanol, and incubated with blocking buffer (5% NHS in PBS). Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies, followed by staining with appropriate secondary antibodies and Hoechst 33258 dye (Molecular probes) to reveal the nuclei. Cover slips were mounted in polyvinyl mounting medium and the cells were viewed and photographed with an Eclipse E800 (Nikon) equipped with a digital camera (CCD-SPOT RT; Diagnostic Instrument) using 60X oil immersion objective. The images were merged and analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (v. 10).

2.7. Quantification of Stress Granules

Cover slips were coded for each independent experiment and all quantifications were done blindly in ~10 separate fields. The percentage of cells with SGs was quantified by counting 200 cells/experiment.

3. Results

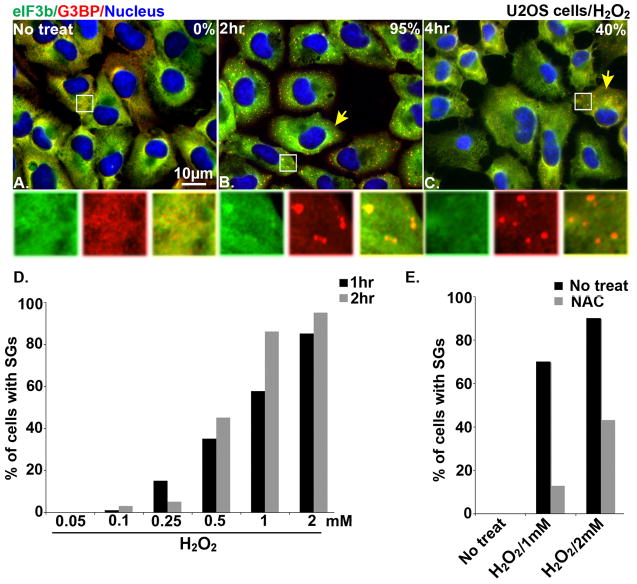

To conclusively determine whether H2O2 induces SG assembly, U2OS cells were first treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 0, 2, and 4 hrs before staining for the SG markers eIF3b and G3BP. As shown in Fig. 1A–C, discrete SGs containing G3BP, but not eIF3b, were induced in cells treated with H2O2 (Fig. 1B, C, yellow arrows). The induction of SGs was transient, as the percentage of cells positive for these G3BP-enriched SGs decreased after 2 hrs of treatment. H2O2 induced SGs in a dose-dependent manner with a minimal effective concentration of 0.1 mM (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

H2O2 induces SGs in U2OS cells. Immunofluorescence microscopy of U2OS cells that were left untreated (A) or treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 2 hr (B) or 4 hr (C) and then stained with SG markers [eIF3b (green) and G3BP (red)]. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst. Insets show enlarged views of individual and merged channels. Yellow arrows point out cells containing SGs. (D) Percentage of U2OS cells with G3BP-positive SGs after 2 hr treatment with 0.05 mM, 0.1 mM, 0.25 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, and 2 mM H2O2. (E) The effect of NAC on H2O2-induced SG assembly. U2OS cells were treated with 50 mM of NAC for 1 hr then treated with 1 mM or 2 mM H2O2 for 2hr before processing for immunofluorescence microscopy.

Since H2O2 is a known inducer of ROS, we tested the effect of N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), a highly potent ROS scavenger [19], on the ability of H2O2 to induce SG assembly. U2OS cells were treated with H2O2 (1 mM or 2 mM for 2hr) after pretreatment with NAC for 1 hr. As shown in Fig. 1E, NAC significantly inhibited SG assembly by H2O2, suggesting that ROS induction by H2O2 treatment is responsible for SG assembly.

The surprising lack of eIF3b in H2O2-induced SGs led us to survey the composition of H2O2-induced SGs. H2O2-induced SGs were probed using the established SG markers TIA-1, PABP, eIF4E (Fig. 2C), HuR, FXR1, RCK (Fig. S1C), G3BP, eIF4G, and eIF3b (Fig. S1G). Interestingly, with all markers tested, we found that H2O2-induced SGs (yellow arrows) (Fig. 2C, Fig. S1C, and G) were smaller and more numerous than SA-induced SGs (Fig. 2B, Fig. S1B, and F). Although some proteins were recruited to SGs induced by both H2O2 and SA, others were only weakly recruited to H2O2-induced SGs as opposed to SA (Fig. 2E). The recruitment of G3BP, FXR1, TIA-1, and HuR to H2O2-induced SGs was as efficient as SA-induced SGs, whereas translation initiation factors, eIF4E, eIF4G, eIF3B and PABP showed significantly weaker recruitment to H2O2-induced SGs compared to those induced by SA (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that SGs induced by H2O2 have different characteristics than those induced by SA.

Fig. 2.

H2O2 induces the assembly of non-canonical SGs. Immunofluorescence microscopy showing non-treated U2OS cells (A; No treat), cells treated with 250 μM sodium arsenite (B; SA) or 2 mM H2O2 (C; H2O2), or cells treated with H2O2 followed emetine treatment (D; H2O2+Em). Yellow arrows indicate SGs stained with SG markers [TIA-1 (green), PABP (red) and eIF4E (blue)]. Insets show enlarged views of individual and merged channels. (E) Percentage of cells with SA- or H2O2-induced SGs that contain the indicated protein markers. The average percentage of cells with SGs is shown (n=3). Error bars indicate the standard deviation. *=P values, that were calculated by comparing the percentage of cells with SGs in SA- and H2O2-treated cells (PABP, p=0.04; eIF4E, p=0.0006; eIF4G, p=0.002; and eIF3b, p=0.004). No other protein markers (G3BP, FXR1, TIA-1, and HuR) showed statistically significant differences. (F) Percentage of cells with SA- and H2O2-induced SGs before and after treatment with emetine. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean (n=3). *=P value<0.005 when comparing the percentages of SGs in SA- or H2O2-treated cells with those treated with emetine.

To confirm that H2O2-induced SGs are bona fide SGs, we tested the effect of emetine, a drug that inhibits SG assembly by preventing polysome disassembly [20]. Treatment with emetine effectively inhibits the assembly of H2O2-induced SGs, similar to arsenite-induced SGs (Fig. 2F, Fig. S1D, and H). Collectively, these results indicate that H2O2 induces bona fide SGs whose size, number, and protein composition are different than SA-induced SGs.

Several reports have shown that H2O2 and SA are both oxidative stressors that induce the phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) [21; 22; 23; 24]. We confirmed that H2O2 induces the phosphorylation of eIF2α in U2OS cells at levels comparable to that induced by SA (Fig. 3A). Since eIF2α phosphorylation was shown to be essential for SG assembly in response to several stresses [25], we determined whether eIF2α phosphorylation is required for H2O2-induced SG assembly. To this end, we used mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in which the endogenous eIF2α is replaced with a non-phosphorylatable mutant (eIF2α S51A) [26]. Whereas SA treatment does not trigger SG assembly in these knock-in (S51A) MEFs (Fig. 3G), pateamine A, which induces SGs in a phospho-eIF2α independent manner, does (Fig. 3H). As shown in Fig. 3E and I, H2O2 induces SGs in both wild-type (WT) and S51A MEFs, demonstrating that eIF2α phosphorylation is dispensable for H2O2-induced SG assembly. We also found that overexpression of a non-phosphorylatable mutant of eIF2α, but not wild-type eIF2α, does not affect H2O2-induced SG assembly (Fig. S2), thus confirming that H2O2-induced SG assembly occurs in a phospho-eIF2α-independent manner. We also found that siRNA-mediated depletion of heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI), an eIF2α kinase that is responsible for SA-induced eIF2α phosphorylation [16], affects neither SG assembly nor eIF2α phosphorylation induced by H2O2 (Fig. S3). These results further support the above observations, and indicate that although both SA and H2O2 induce oxidative stress, they activate different eIF2α kinases.

Fig. 3.

H2O2 induces SGs independent of eIF2α phosphorylation. (A) Western blot analysis of phospho-eIF2α (upper panel) in U2OS cells treated with different concentrations of H2O2 (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM) as well as 250 μM sodium arsenite (SA). TIA-1 (lower panels) was used as a loading control. (B–I) Immunofluorescence microscopy showing SG assembly induced by H2O2 in wild type (WT MEFs) and S51A eIF2α mutant MEFs (S51A MEFs). Yellow arrows indicate representative G3BP+ SGs (green) in untreated U2OS cells (B and F), or cells treated with 200 μM sodium arsenite (SA) (C and G), 50 nM pateamine A (PA) (D and H), and 2 mM H2O2 (E and I). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst.

Inhibition of translation initiation correlates well with SG assembly in cells subjected to different types of stresses [3; 4]. Since H2O2 inhibits global protein synthesis [22; 23; 24; 27] in different types of cells primarily at the level of translation initiation [23; 24; 28] it is likely that H2O2 targets the translation initiation machinery and thus induces SG formation. To test this hypothesis, we pulled down the eIF4F complex from lysates of SA or H2O2- treated U2OS cells using m7GTP-Sepharose (Figure 4A). Although SA had no effect on the assembly of the eIF4F complex, remarkably, H2O2 significantly disrupted the eIF4E complex. This analysis revealed that H2O2 displaces eIF4G and eIF4A from eIF4E (Fig. 4A), and at the same time, H2O2 promotes interactions between 4E-BP1 and eIF4E.

Fig. 4.

H2O2 induces SGs by targeting eIF4F. (A) H2O2 causes eIF4F complex disruption and enhances eIF4E:4E-BP1 interactions. U2OS cells without (No treat) or with drug treatment (sodium aresenite (SA) and H2O2) were assembled on m7GTP-Sepharose as described in [18]. Loading control (Input) and the m7GTP-bound proteins (m7GTP-beads) were analyzed by Western Blotting using antibodies against eIF4G, eIF4A, eIF4E and 4E-BP1. (B) Western blot analysis showing the knockdown efficiency of eIF4E in U2OS cells transfected with control siRNA (si-Ctrl) or eIF4E-specific siRNA (si-4E). TIA-1 was used as a loading control. (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy showing SG assembly in U2OS cells after eIF4E depletion. Cell treated with the indicated siRNAs were left untreated (No treat, upper panels) or treated with 250 μM SA (middle panels), or 2 mM H2O2 (lower panels) and then stained with SG markers G3BP (red) and TIA-1 (green). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst. Insets show enlarged views of individual and merged channels. (D) Percentage of cells with SGs after eIF4E depletion. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean (n=3, *p= 0.00036)

It has been well documented that hypophosphorylated 4E-BP1 isoforms binds to eIF4E to displace eIF4G and inhibit translation initiation [29; 30]. Since H2O2 causes hypophosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in several cell lines [23; 24; 28], it was of our interest to determine whether 4E-BP1 is also hypophosphorylated under our treatment conditions. Western blot analysis done on U2OS cell lysates revealed that H2O2 treatment significantly increases levels of hypophosphorylated 4E-BP1 (Fig. S4A) by blocking 4E-BP1 phosphorylation compared to that observed in untreated cells (Fig. S4A, lane 1, asterisk). Furthermore, we found that H2O2 (but not SA) re-localizes eIF4E, and its transporter protein 4E-T, from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Fig. S4B and C). Taken together, these results suggest that H2O2 induces hypophosphorylation of 4E-BP1 to increase its association with eIF4E and inhibit translation initiation. This, in turn, results in the assembly of a unique class of SGs.

To determine whether eIF4E:4E-BP1 interaction is essential for H2O2-induced SG assembly, U2OS cells were transfected with control or eIF4E-directed siRNAs and then left untreated or treated with H2O2 or SA. Western blot analysis verified that siRNAs targeting eIF4E downregulated eIF4E protein levels (Fig. 4B). We found that depletion of eIF4E resulted only in a minor decrease in SG assembly induced by SA (Fig. 4C). In contrast, eIF4E depletion strongly inhibited H2O2-induced SG assembly (~80%) (Fig. 4C, D). Knockdown of 4E-BP1 also affected H2O2-induced SG assembly, resulting in smaller, less discrete SGs (Fig. S5). These data suggest that eIF4E:4E-BP1 complexes play an essential role in the H2O2-induced assembly of SGs.

4. Discussion

SG assembly results from dynamic re-modeling of global translation in cells subjected to a variety of environmental stresses [3; 4]. Although SG assembly is a conserved phenomenon in a wide range of eukaryotes, the assembly and composition of SGs clearly demonstrate species-specific and stress-specific differences. Mammalian SGs assembled in response to stress-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α are composed of 40S ribosomal subunits in association with the cap-binding complex (eIF4E, eIF4A and eIF4G), PABP and subunits of eIF3 [3; 4]. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, different stresses assemble SGs with distinct compositions. Exposure to the metabolic poison sodium azide induces the assembly of SGs whose composition resembles that of mammalian SGs [31]. In contrast, glucose deprivation induces the assembly of granules that contain eIF4E, eIF4G and PABP (so-called “EGP-bodies) but lack 40S ribosomal subunits and eIF3 subunits [32]. Our results reveal that in mammalian cells, SG composition also differs in a stress-dependent manner.

Although arsenite-induced oxidative stress is the best-characterized inducer of SGs in mammalian cells, the ability of H2O2 to trigger SG assembly has been controversial. Whereas some studies show that H2O2 induces SG assembly [8; 9; 10], other studies report that H2O2 does not trigger SG assembly [6; 7; 11]. Here, we demonstrate that in U2OS cells H2O2 clearly induces SGs that are different from canonical SGs. First, H2O2-induced SGs are formed transiently and they are morphologically smaller and more abundant than SA-induced granules. Second, H2O2-induced SGs have significantly reduced amounts of eIF3, eIF4E and eIF4G indicating that these granules are different from both yeast EGP-bodies and canonical mammalian SGs. Third, although H2O2 induces eIF2α phosphorylation similarly to SA, the phospho-eIF2α itself is not required for H2O2-induced SGs in contrast to SA-induced SGs. In this regard, H2O2 resembles the xenobiotic compounds pateamine A (Pat A) and hippuristanol, the anti-inflammatory lipid mediator 15d-PGJ2 and stress-induced tRNA-derived RNAs (tiRNAs) that all trigger eIF2α-independent SG assembly [12; 33; 34; 35]. Whereas PatA, hippuristanol, and 15d-PGJ directly bind and inhibit eIF4A [33; 34; 36] and tiRNAs displace eIF4A:eIF4G from cap-bound eIF4E [18], H2O2 indirectly promotes binding of 4E-BP1 to eIF4E by promoting 4E-BP1 hypo-phosphorylation. This raises the possibility that mTOR which regulates 4E-BP1 phosphorylation might be involved in H2O2-induced SG assembly. Moreover, in contrast to SA-induced SG assembly, eIF4E itself is required for H2O2-induced SG assembly suggesting that the eIF4E/4E-BP1 complex may directly promote the aggregation of untranslated mRNAs.

In summary, our data suggest that mammalian cells can assemble different types of SGs utilizing different mechanisms. These different routes of assembly are stress-specific and dictate recruitment of selective SG constituents. What are the possible functions of different classes of SGs? In analogy to amino acid starvation-induced SGs that selectively sequester mRNAs bearing 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine tracts [37; 38], we propose that different classes of SGs selectively recruit specific mRNAs from translating ribosomes. In turn, this selective mRNA re-localization causes stress-specific changes in protein translation allowing adaptation to stress conditions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

H2O2 induces SGs in an eIF2α-independent manner

H2O2-induced SGs are compositionally distinct from canonical SGs

The cap-binding eIF4F complex must be disassembled for H2O2-induced SG assembly

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Paul Anderson’s lab for technical supports and comments. This work was supported by NIH grants AI033600 and AI065858 (P.A.), by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad (K.F.) and by a Research Development Grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (ID158521, P.I.).

Appendix A

Supplementary data associated with this article (Supplementary Figures 1–5) can be found online.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yamasaki S, Anderson P. Reprogramming mRNA translation during stress. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules. Curr Biol. 2009;19:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:803–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arimoto K, Fukuda H, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Saito H, Takekawa M. Formation of stress granules inhibits apoptosis by suppressing stress-responsive MAPK pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/ncb1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim WJ, Back SH, Kim V, Ryu I, Jang SK. Sequestration of TRAF2 into stress granules interrupts tumor necrosis factor signaling under stress conditions. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2450–2462. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2450-2462.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JA, Roberts TL, Richards R, Woods R, Birrell G, Lim YC, Ohno S, Yamashita A, Abraham RT, Gueven N, Lavin MF. A novel role for hSMG-1 in stress granule formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4417–4429. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05987-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pothof J, Verkaik NS, Hoeijmakers JH, van Gent DC. MicroRNA responses and stress granule formation modulate the DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3462–3468. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf A, Krause-Gruszczynska M, Birkenmeier O, Ostareck-Lederer A, Huttelmaier S, Hatzfeld M. Plakophilin 1 stimulates translation by promoting eIF4A1 activity. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:463–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kedersha N, Anderson P. Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol. 2007;431:61–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emara MM, Ivanov P, Hickman T, Dawra N, Tisdale S, Kedersha N, Hu GF, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10959–10968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kedersha N, Tisdale S, Hickman T, Anderson P. Real-time and quantitative imaging of mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol. 2008;448:521–552. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Xu B, Liu L, Luo Y, Yin J, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Huang S. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits mTOR signaling by activation of AMPKalpha leading to apoptosis of neuronal cells. Lab Invest. 2010;90:762–773. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kedersha N, Chen S, Gilks N, Li W, Miller IJ, Stahl J, Anderson P. Evidence that ternary complex (eIF2-GTP-tRNA(i)(Met))-deficient preinitiation complexes are core constituents of mammalian stress granules. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:195–210. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohn T, Kedersha N, Hickman T, Tisdale S, Anderson P. A functional RNAi screen links O-GlcNAc modification of ribosomal proteins to stress granule and processing body assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1224–1231. doi: 10.1038/ncb1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamasaki S, Ivanov P, Hu GF, Anderson P. Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress-induced translational repression. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:35–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zafarullah M, Li WQ, Sylvester J, Ahmad M. Molecular mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine actions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:6–20. doi: 10.1007/s000180300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kedersha N, Cho MR, Li W, Yacono PW, Chen S, Gilks N, Golan DE, Anderson P. Dynamic shuttling of TIA-1 accompanies the recruitment of mRNA to mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1257–1268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant CM. Regulation of translation by hydrogen peroxide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 15:191–203. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacCallum PR, Jack SC, Egan PA, McDermott BT, Elliott RM, Chan SW. Cap-dependent and hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation are modulated by phosphorylation of eIF2alpha under oxidative stress. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3251–3262. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel J, McLeod LE, Vries RG, Flynn A, Wang X, Proud CG. Cellular stresses profoundly inhibit protein synthesis and modulate the states of phosphorylation of multiple translation factors. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:3076–3085. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenton D, Smirnova JB, Selley JN, Carroll K, Hubbard SJ, Pavitt GD, Ashe MP, Grant CM. Global translational responses to oxidative stress impact upon multiple levels of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29011–29021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kedersha NL, Gupta M, Li W, Miller I, Anderson P. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2 alpha to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1431–1442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheuner D, Song B, McEwen E, Liu C, Laybutt R, Gillespie P, Saunders T, Bonner-Weir S, Kaufman RJ. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godon C, Lagniel G, Lee J, Buhler JM, Kieffer S, Perrot M, Boucherie H, Toledano MB, Labarre J. The H2O2 stimulon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22480–22489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mascarenhas C, Edwards-Ingram LC, Zeef L, Shenton D, Ashe MP, Grant CM. Gcn4 is required for the response to peroxide stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2995–3007. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gingras AC, Raught B, Gygi SP, Niedzwiecka A, Miron M, Burley SK, Polakiewicz RD, Wyslouch-Cieszynska A, Aebersold R, Sonenberg N. Hierarchical phosphorylation of the translation inhibitor 4E-BP1. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2852–2864. doi: 10.1101/gad.912401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oulhen N, Boulben S, Bidinosti M, Morales J, Cormier P, Cosson B. A variant mimicking hyperphosphorylated 4E-BP inhibits protein synthesis in a sea urchin cell-free, cap-dependent translation system. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchan JR, Yoon JH, Parker R. Stress-specific composition, assembly and kinetics of stress granules in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 124:228–239. doi: 10.1242/jcs.078444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoyle NP, Castelli LM, Campbell SG, Holmes LE, Ashe MP. Stress-dependent relocalization of translationally primed mRNPs to cytoplasmic granules that are kinetically and spatially distinct from P-bodies. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:65–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bordeleau ME, Mori A, Oberer M, Lindqvist L, Chard LS, Higa T, Belsham GJ, Wagner G, Tanaka J, Pelletier J. Functional characterization of IRESes by an inhibitor of the RNA helicase eIF4A. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:213–220. doi: 10.1038/nchembio776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim WJ, Kim JH, Jang SK. Anti-inflammatory lipid mediator 15d-PGJ2 inhibits translation through inactivation of eIF4A. EMBO J. 2007;26:5020–5032. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dang Y, Kedersha N, Low WK, Romo D, Gorospe M, Kaufman R, Anderson P, Liu JO. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha-independent pathway of stress granule induction by the natural product pateamine A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32870–32878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low WK, Dang Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, Shi Z, Choi NS, Merrick WC, Romo D, Liu JO. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation by the marine natural product pateamine A. Mol Cell. 2005;20:709–722. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Damgaard CK, Lykke-Andersen J. Translational coregulation of 5′TOP mRNAs by TIA-1 and TIAR. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2057–2068. doi: 10.1101/gad.17355911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivanov P, Kedersha N, Anderson P. Stress puts TIA on TOP. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2119–2124. doi: 10.1101/gad.17838411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.