Abstract

Metabolomics is increasingly being utilized in cancer biology for biomarker discovery and identification of potential novel therapeutic targets. However, a systematic metabolomics study of multiple biofluids to determine their interrelationships and to describe their utility as tumor proxies is lacking. Using a mouse xenograft model of kidney cancer, characterized by sub-capsular implantation of Caki-1 clear cell human kidney cancer cells, we examined tissue, serum, and urine all obtained simultaneously at baseline (urine) and at, or close to, animal sacrifice (tissue and plasma). Uniform metabolomics analysis of all three “matrices” was accomplished using GC- and LC-MS. Of all the metabolites identified (267 in tissue, 246 in serum, 267 in urine), 89 were detected in all 3 matrices, and the majority were altered in the same direction. Heat maps of individual metabolites showed that alterations in serum were more closely related to tissue than was urine. Two metabolites, cinnamoylglycine and nicotinamide, were concordantly and significantly (when corrected for multiple testing) altered in tissue and serum, and cysteine-glutathione disulfide showed the highest change (232.4-fold in tissue) of any metabolite. Based on these and other considerations, three pathways were chosen for biological validation of the metabolomic data, resulting in potential therapeutic target identification. These data show that serum metabolomics analysis is a more accurate proxy for tissue changes than urine, that tryptophan degradation (yielding anti-inflammatory metabolites) is highly represented in renal cell carcinoma, and support the concept that PPAR-alpha antagonism may be a potential therapeutic approach for this disease.

INTRODUCTION

The use of metabolomics to identify tumor biomarkers as well as potential targets for therapy has entered mainstream clinical medicine and is beginning to lead to payoffs in kidney (1, 2), prostate(3), and pancreatic (4) cancer, as well as in kidney disease in general (5). While most of the existing published studies in the field have focused on either tumor tissue or a specific biofluid for metabolomics analysis, there are limited available data examining the utility of a biofluid to serve as a proxy for tumor metabolomic changes through simultaneous examination of tissue in addition to several biofluids. Because the ultimate purpose of a metabolite biomarker is to reflect biochemistry of the tumor of interest, it is essential to determine how metabolomic profile changes occurring in a tumor are reflected in blood and urine.

To begin to address this question, as well as to extend our ongoing work in kidney cancer metabolomics and biomarker discovery, we used a xenograft mouse model of highly metastatic RCC represented by subcapsular implantation of human Caki-1 cells. This disease model has the advantage of closely recapitulating human RCC in that the cancer cells are implanted under the renal capsule, using sham surgery animals to control for any metabolic changes which might occur after surgical stress. From this model we obtained terminal tissue, serum, and urine simultaneously, and we performed global metabolomics analysis on each matrix using identical analytical platforms and run at the same time.

We now show that most of the identified metabolites which were detected in all 3 matrices were concordant in their direction of change, and that blood serves as a more accurate proxy of tissue change than does urine, as the magnitude of metabolite changes in each matrix show a gradation from tissue (most) to serum to urine (least). Consistent with other published studies in RCC (1, 6, 7), and to further confirm the veracity and consistency of our data, we biologically validated several relevant pathways whose signatures were significantly altered in one or several matrices, specifically the tryptophan metabolism pathway, which is linked to immunosuppressive metabolites. In addition, from the finding that the two metabolites which were altered in all 3 matrices are present in the peroxisome proliferator pathway, the target receptor PPAR-α was identified and validated in vitro. Thus, global metabolomics of a mouse xenograft model indicates that serum, and to a lesser extent urine, demonstrates utility as proxies for tumoral metabolite changes. Furthermore, validation of several identified altered pathways suggests that these could be further evaluated as potential markers and therapeutic targets for this disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Four human proximal tubule epithelial cancer cell lines, ACHN, A498, 786-O, and Caki-1, and one “normal” derived kidney epithelial cell line, HK-2, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Primary proximal renal tubular epithelial cells (NHK) were from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). All ATCC and Lonza cell lines undergo extensive authentication tests during the accessioning process as described in vendor websites. ACHN, A498 and HK-2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, and Caki-1 and 786-O cells were maintained in RPMI, all supplemented with 10% FBS, and 100units/ml streptomycin and 100 μg/ml penicillin. Cells were maintained at 5% CO2 at 37°C. Lipopolysaccharide, 1-methyl-L-tryptophan (1-MT), WY-14,643, GW6471, and β-actin anti-mouse antibody were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). COX-2 anti-rabbit antibody was generously provided by Daniel Hwang (UC Davis, CA). Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail for immunoblotting was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI).

Mouse subcapsular xenograft model

Human Caki-1 cells (106) were mixed with 30% of non-growth factor reduced matrigel (BD) and injected into the right flanks of two donor nude mice. After the tumors reached 500 mm3 of size, mice were sacrificed and tumors excised to prepare tumor cell suspension. Tumors were minced and passed through 70 μM Nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon) and washed with PBS to collect cell pellets. Tumor cells were resuspended in 30% matrigel (106 cells /20 μl /mouse) for renal subcapsular implantation. Nude mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and the kidneys were exteriorized for subcapsular injection. The sham control group of mice received no injection of tumors. After injection, the kidney was returned to the abdominal cavity and the peritoneum and skin were closed by suture and metal wound clips, respectively. All of the mice were sacrificed when the xenografted animals became moribund, 34 days after surgery. Kidney plus tumor size averaged 1.62 grams at sacrifice. Terminal serum was collected, and tumor (from xenografted animals) and normal kidneys (from sham surgery animals) were removed and split for snap freezing and 10% buffered formalin fixation at sacrifice. For urine, we collected at 2 time points, one day before surgery and 32 days after surgery (two days prior to sacrifice). From the frozen tissue, tumors were dissected out from adjacent non-cancerous tissue, and this as well as sham control kidneys were subjected to non-targeted metabolomic analysis.

MTT assay

5 × 104 cells were plated in 96 well plates and incubated for 16 hours at 5% CO2 at 37°C. After appropriate treatments, the cells were incubated in 20 μl of thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) with 180 μl of the growth medium for three hours. Then, the MTT solution was removed and the blue crystalline precipitate in each well was dissolved in DMSO (200 μl). Visible absorbance of each well at 540 nm was quantified using a microplate reader.

Immunoblotting

Cells were treated with either vehicle, LPS, or 1-MT for 72 hours. The cells were then lysed, protein was collected, and immunoblotting was carried out as previously described (8).

Non-targeted metabolomic analysis

The metabolomic platforms, including sample extraction process, instrumentation configurations and conditions, and software approaches for data handling, were previously described in detail (1, 9). Urinary metabolite values were creatinine-normalized to account for urine concentration differences among samples and tissue samples were normalized to equal mass prior to chromatographic analysis. Due to space restrictions, these techniques are further described in Supplemental Data.

Statistical methods

Processing of the raw data yielded 299 known metabolites from tissue, 251 from serum, and 274 from urine samples from xenograft and sham surgery mice. For each matrix, metabolites observed in fewer than three of the samples from each of the experimental groups (xenograft and sham surgery) were excluded. This screening resulted in 267, 246, and 267 metabolites for tissue, serum and urine, respectively that were subsequently statistically analyzed. Missing metabolite values were imputed using the minimum observed metabolite value. Prior to statistical analyses, metabolite intensities were log (base 2) transformed to meet underlying assumptions of normality with a constant variance and to reduce the dominant effect of extreme values. Prior to log transformation, urinary metabolite values were creatinine-normalized to account for urine concentration differences among samples.

The primary objective of the statistical analysis was to identity metabolites in each matrix whose concentration differentiates xenograft and sham surgery mice that potentially could serve as diagnostic biomarkers for kidney cancer as well as to elucidate alterations of metabolite signals in pathways associated with the presence of kidney cancer. To identify metabolites as potential diagnostic biomarkers for mice with kidney cancer, we aimed to 1) identify metabolites that distinguish xenograft and sham surgery mice using differential analysis, and 2) identify sets of relevant metabolites that act synergistically within functionally-defined pathways using functional score analysis.

For each tissue and serum metabolite, we identified differentially expressed metabolites between xenograft mice and sham surgery mice using t-tests. For urine, because we measured twice at a day before surgery and 32 days after surgery from the same animals, we used an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to identify differentially regulated metabolites, modeling post-surgery metabolite values as a function of cancer status with pre-surgery metabolite values included as a covariate. Significance was determined based on a permutation null distribution consisting of 6,435 permutations for tissue and serum and 3,432 permutations for urine. The number of permutations was lower for urine because we had one less sample (i.e., urine samples from seven xenograft mice and seven sham surgery mice) available for the statistical analysis. False discovery rates (FDRs) were also calculated to account for multiple testing. We also conducted a partial least squares (PLS) regression analysis for each matrix separately using all metabolites. For urine, we used the post surgery values only for consistency with the other matrices. Leave-one-out cross validation was conducted using up to 10 latent components. R2 was calculated as a measure of the amount of variability explained by the PLS regression while the Q2 values was a measure of the predictive error of the regression. For each metabolite, the Variable Importance in the Projection (VIP) score was calculated to determine a metabolite’s influence on predicting the outcome as well as its weight in the predictor matrix, while considering the presence of multicollinearity among metabolites.

RESULTS

Metabolomic analysis of all 3 matrices shows similarities among matrices

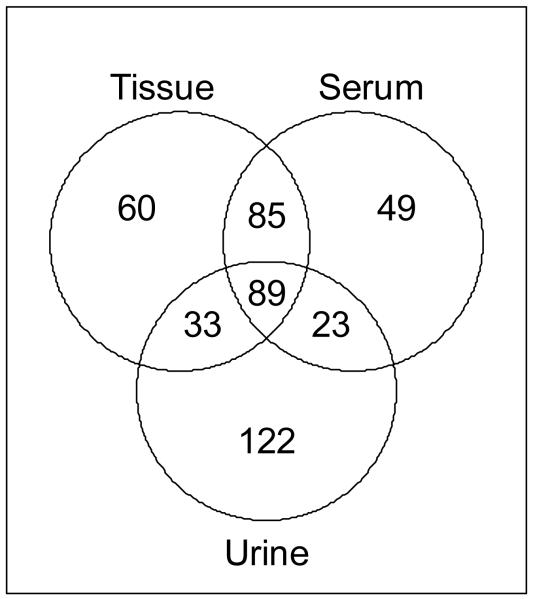

Eight nude mice were implanted with Caki-1 cells under the renal capsule, and seven control mice of identical genetic background were subjected to sham surgery. Utilized urines were collected one day before surgery and 32 days after surgery (i.e. two days prior to sacrifice). Blood (as serum) and kidney tissue were obtained simultaneously from all animals at sacrifice (34 days after surgery); the tumor + kidney weights at sacrifice averaged are given in Supplemental Table 1. All samples were subjected to simultaneous global metabolomics analysis by LC- and GC-MS as described in Materials and Methods and Supplemental Data. The 267 metabolites identified from tissue, 246 from serum, and 267 from urine were used for further downstream analyses. As expected, many of the metabolites identified in one matrix were also found in the other(s). Of the suite of identified metabolites, 89 were detected in all 3 matrices (Fig. 1). Tissue and serum had the most identified metabolites in common, with 174 metabolites identified in both of these matrices. Interestingly, urine had fewer metabolites in common with the other matrices and had the largest number (122) of unique metabolites. Thus, there exists a closer link between tissue and serum metabolic profiles than between tissue and urine.

Fig. 1.

Venn diagram of all identified metabolites in each matrix

Tissue and the indicated biofluids were analyzed by GC- and LC-MS and those metabolites identified in each of the 3 matrices are shown.

One goal of a biofluid study for biomarker discovery, especially in kidney cancer, is to determine whether easily accessible fluids (blood and urine in this case) can serve as proxies for what is occurring in the tumor tissue. About two-thirds of the 89 metabolites found in all 3 matrices were altered in the same direction (Table 1) supporting the hypothesis that metabolic changes in tissue are reflected in serum and urine. Notably, about one-third of the metabolites were altered in the opposite direction in biofluids as compared to tissue. Thus, while consistent changes in some metabolites can potentially be traced through all three matrices, other metabolites show differential regulation patterns which may be consistent with the existence of nodes or convergence points in metabolic pathways.

Table 1.

Number of metabolites altered in the same direction (concordant) and opposite direction (discordant) between tissue, serum and urine.

| Tissue vs. Serum | Tissue vs. Urine | Serum vs. Urine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant | 60 | 58 | 61 |

| Discordant | 29 | 31 | 28 |

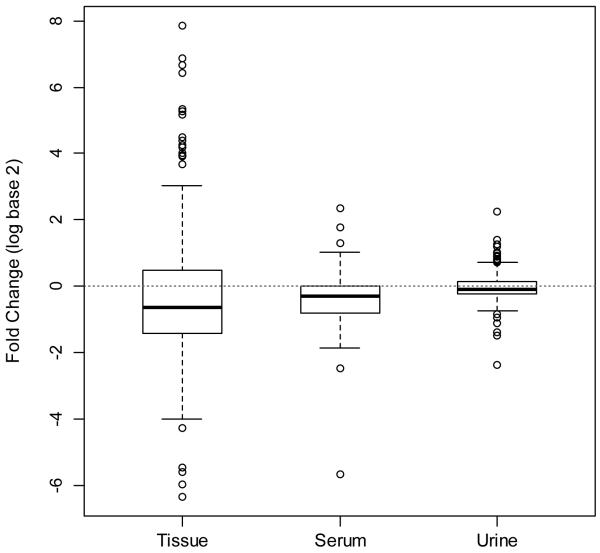

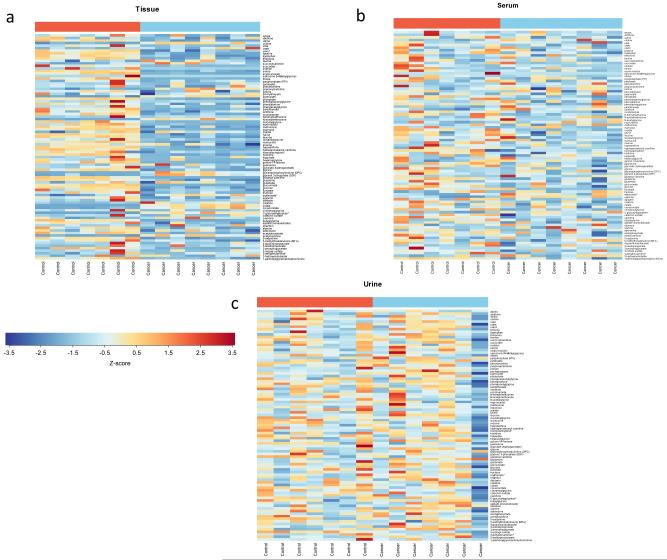

While most metabolites were altered in the same direction across the three matrices, metabolic differences between xenograft and sham surgery mice were most pronounced in tissue followed by serum and urine (Fig. 2). When metabolite changes in cancer vs. control animals are compared using heatmap visualization, it becomes obvious that differences in tissue metabolites between cancer and control are more pronounced than these differences in serum or in urine (Fig. 3a-c). This observation is also supported by R2 and Q2 values adapted to evaluate the prediction performance of PLS (Supplemental Table 2). R2 values were high for all the three matrices when used the first two or more components, suggesting the model fitness is good. Q2 values for serum were considerably smaller than for tissue but higher than urine. The finding that serum changes between cancer and control animals are more marked than urine is expected, because blood is in intimate contact with the tumor due to its abundant angiogenesis (especially in RCC), and urine is subjected to additional processing of the plasma by the kidneys.

Fig. 2.

Variation in metabolites in each matrix

Distribution of fold change (log2) of metabolites between xenograft and sham surgery mice in the three matricesDotted line shows a log2 fold change of 1 indicating no difference between xenograft and sham surgery.

Fig. 3.

Heatmaps for each matrix of the 89 metabolites in common.

The color of each section is proportional to the significance of change of metabolites (red=upregulated; blue=downregulated) in (a) tissue, (b) serum, and (c) urineTissue and serum values are z-scores of raw intensities of each metaboliteFor urine, values are z-scores of creatinine-normalized metabolite intensities in urine obtained 2 days before sacrifice in both cancer and corresponding control animals.

Inter-matrix comparison reveals common biochemical function among matrices

Metabolites with large changes in tissue, and showing concordant and detectable changes in serum and/or urine, are the most logical candidates for potential biomarkers. Consequently, in order to evaluate specific metabolites as potential biomarkers, we next identified metabolites that significantly differed between xenograft and sham surgery control mice but with particular attention to shared metabolites altered in the same direction (i.e. concordant) among all matrices. Tissue had the largest number of differentially regulated metabolites with 186 of the 267 metabolites in this matrix differing significantly at FDR<0.05 between xenograft and sham surgery mice (Supplemental Table 3a). In serum, 76 of 246 differed significantly at FDR<0.05 (Supplemental Table 3b), and in urine no metabolites were statistically significantly different (Supplemental Table 3c). The VIP scores obtained by the PLS regression for selecting most relevant metabolites which have a significant effect on separation between sham surgery and control samples were in agreement with the (FDR) p-values from the differential analysis in terms of significance (Supplemental Table 4). Interestingly, urine has higher VIP scores compared to tissue and serum, which implies a lower proportion of relevant metabolites or a higher magnitude of correlation among metabolites with similar effects on the separation.

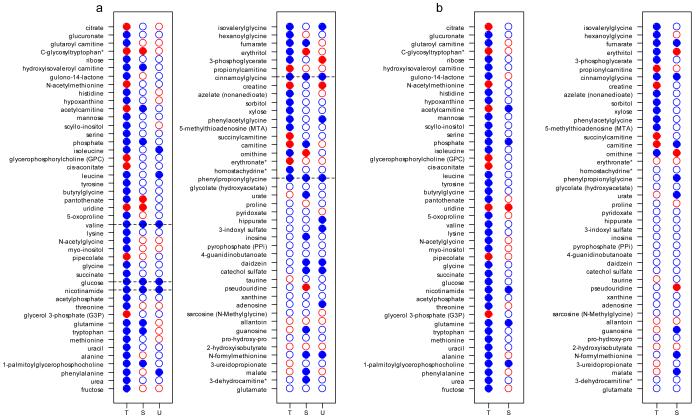

When examined across all 3 matrices, 5 metabolites (cinnamoylglycine, glucose, nicotinamide, phenylpropionoylglycine, and valine) were significantly down-regulated in tissue and serum at FDR <0.05 and close to significane in urine, all with FDR <0.1 and raw p-value < 0.01 (Fig. 4a). Looking at tissue and plasma together, there were a plethora of metabolites which were significantly and concordantly altered in these matrices, including two metabolites which are regulated by modulators of PPAR-α (nicotinamide and cinnamoylglycine) (Fig. 4b). These findings suggest modulation of specific pathways by the presence of the tumor and thus identification of potential therapeutic targets (see below).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of metabolites across matrices

- using raw p-values

- using FDRs

Validation of tissue pathways supports veracity of the metabolomics data

In any high-throughput metabolomics study, key metabolic pathways, as suggested by statistical significance, need to be validated in benchtop experiments to ensure the veracity of the metabolomics data and to identify biological correlates. Rationales for selection of metabolites in the discovery stage for further validation can include statistical significance and/or biological evidence, such as the relative changes of metabolite expression in cancer compared to control, or functional relevance of the metabolites as evidenced by their involved in the same pathway. For such validation, we have chosen two separate pathways or metabolites based on the findings as discussed above: (1) the PPAR-α pathway which is associated with the metabolites which were significantly altered in tissue and serum at FDR<0.05 and in urine using less stringent FDR<0.1 and raw p-value <0.01 (cinnamoylglycine and nicotinamide); and (2) the tryptophan degradation pathway in which we have seen significant changes in metabolites in human urine [2] as well as in the mouse tissue described here.

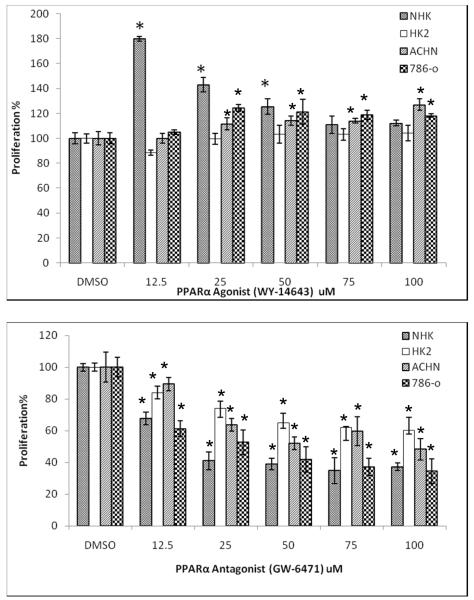

PPAR-α modulation results in alteration of cell growth

As mentioned above, nicotinamide and cinnamoylglycine were 2 of the 5 significantly and concordantly changed (attenuated) in association with the cancer state in all 3 matrices (by FDR<0.05 in tissue and blood and by FDR<0.1 in urine; Fig. 4), and these compounds are altered by peroxisome proliferators.. The PPAR-α pathway is known to regulate key enzymes of the tryptophan pathway (10) which leads, through quinolinate (found elevated in a previous study (1)), to production of NAD+. NAD+ is a strong reducing agent and is involved to a large degree with cellular energetics and other electron donor processes. Animals fed the PPAR-α agonist Wy-14,643 showed altered urinary levels of nicotinamide and cinnamoylglycine (11). Relevant to RCC, other investigators utilized siRNA to attenuate PPAR-α in Caki-1 cells to demonstrate that this receptor regulates genes involved in fatty acid metabolism (12). These findings suggested that PPAR-α may be involved in tumor promotion or attenuation and prompted us to explore this nuclear receptor as a possible target in RCC. When incubated with several RCC cell lines, as well as a “normal” renal tubular epithelial cell line (HK-2), and primary RTE cells (NHK), the PPAR-α agonist Wy-14,643 increased cell proliferation, whereas the PPAR-α antagonist GW6471 had the opposite effect and was considerably more pronounced (Fig. 5). To recapitulate these data in cells, we utilized the Caki-1 cell line and showed the expected effects of the PPAR-α agonist Wy-14,643 upon tryptophan and nicotinamide levels (11, 13)(Supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, PPAR-α may be a viable target for RCC therapy with PPAR-α antagonism resulting in significant inhibition of cell proliferation.

Fig. 5.

PPAR-α modulation affects RCC and other renal epithelial cell lines

The indicated cell lines (NHK = primary human renal tubular epithelial cells) were grown to confluence and incubated continuously with the indicated concentrations (10-100 μM) of the PPAR-α agonist Wy-14,643 or antagonist GW6471An MTT assay was performed as described in Experimental ProceduresThe experiment shown is representative of 3 experimentsAsterisks indicate significance at a p-value<0.05 when compared to the DMSO treated control for that cell line.

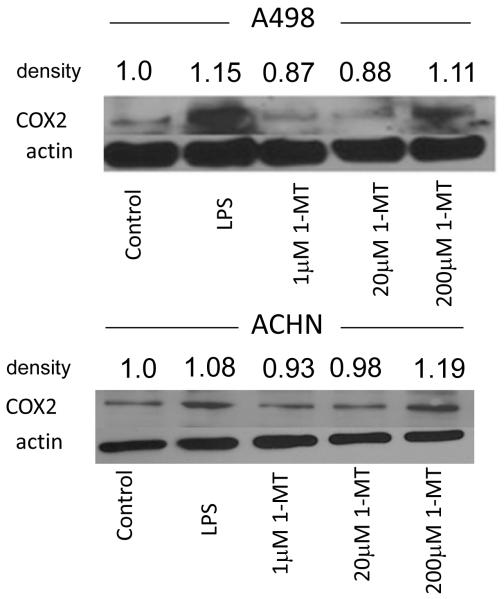

Attenuation of the tryptophan degradation pathway results in higher levels of inflammatory markers and may contribute to immune escape

By metabolomics analysis of tumor tissue, the tryptophan level was significantly lower (0.69 fold, FDR= 0.0024), and the downstream metabolite kynurenine was significantly elevated (2.78 fold, FDR=0.0008) compared to controls. Our previous study utilizing human urine showed that quinolinate, another downstream metabolite in addition to kynurenine, was elevated in human RCC (1). Taken together, these data indicate that tryptophan metabolism is increased in RCC, resulting in the decrease of tryptophan and the accumulation of downstream metabolites in xenograft tumor tissue and serum, and the accumulation of such metabolites in human urine.

In our earlier metabolomics and proteomics studies, we have frequently observed altered tryptophan metabolism (1, 7). It has been shown that increased tryptophan metabolism is associated with both decreased proliferation of T cells and a reduced immune response, mediated by the enzyme indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (14, 15); patients with ovarian, endometrial, hepatocellular, and colorectal carcinomas have all been shown to have chronically activated IDO (14). Thus, to further validate the metabolomics data (in addition to our previously published work cited above), we reduced the accumulation of the downstream metabolites by inhibiting IDO and assessed the inflammatory response in the tumor cells. RCC cell lines were treated with the specific IDO inhibitor 1-MT, and COX2 induction, as a measure of inflammation (16), was detected by immunoblot (Fig. 6). A dose of 200μM of 1-MT significantly induced COX2 expression in A498 and ACHN cancer cells, thus decreased tryptophan metabolism mediated by IDO promotes inflammation. In addition, using a ACHN cell culture model, we showed a slight dose-dependent increase in tryptophan in cells treated with 1-MTT (Supplemental Fig.2), supporting the importance of this pathway in RCC. The changes in the cell lines were less pronounced than in the tissue given the considerably lower number of cells in the former compared to the latter. These results in aggregate suggest RCC tumors prevent an inflammatory response by increasing tryptophan metabolism, a means by which RCC is able to evade immune surveillance.

Fig. 6.

1-methyltryptophan increases an inflammatory marker in cancer cells

The RCC cell lines A498 and ACHN were grown to confluence and treated for 72 hours with 1-methyltryptophan as indicatedWhole cell protein extracts were then run using 10% SDS-PAGE and incubated with the indicated antibodiesActin is a loading control and LPS is a positive controlThe experiments shown are representative of 3 independent experimentsDensitometry measurements are shown for this blot: incubation of both cell lines with 1-MT at 200 μM was significant (p=0.015 for A498 and p=0.034 for ACHN).

DISCUSSION

The clinical use of omics technologies in cancer research has evolved from the direct evaluation of tumor tissue searching for prognostic markers to the use of biofluids as proxies for changes in the cancer of interest. While it is clear that the latter approach is more readily translatable to the clinical setting, there are no currently available studies demonstrating the utility or accuracy of biofluids as a reflection of metabolomic changes within tumor tissue. That a specific biofluid can reflect metabolic changes in a cancer is a reasonable assumption, since the concept behind the use of the clinical laboratory for blood chemistries assumes that tests for liver and kidney function, for example, accurately reflect changes that are occurring in these organs. Consistent with this concept, recent metabolomics studies, including some from our laboratory, have assumed that changes in the blood and urine metabolomes accurately reflect alterations in metabolic processes which are occurring in the tumor itself (as well as in any systemic effects of the malignancy), but prior to the current study, this assumption has not been validated. For these reasons, we have undertaken a comprehensive metabolomics analysis of tissue, blood, and urine taken simultaneously from an anatomically accurate RCC mouse xenograft model. In light of the data obtained from this study, it is evident that blood is a decent proxy of tumoral metabolomic changes, whereas urine is less reflective of such changes.

Some of the suite of metabolomic changes seen here can be correlated to changes in metabolic pathways. In particular, glycolysis and the citric acid cycle are involved in the Warburg effect, and the examination of individual metabolites in these pathways shows that citrate, which is 21-fold increased in cancer tissue (FDR p-value=0.0005), is also increased in urine (although non-significantly in the current study) as a possible tissue proxy. It is highly likely that, while tissue glycolysis is elevated in our analysis consistent with the Warburg effect, it is being shunted into biosynthetic pathways rather than through the citric acid cycle as is evidenced by significantly lower tumor levels of fumarate (0.6525-fold, FDR=0.0029; see Supplemental Table 2a). In addition, the acylcarnitines, which we have shown to be increased in the urine of RCC patients (17), were found to be increased consistently in tissue (e.g. acetylcarnitine increased 3.2016-fold, FDR=0.0005; butyrylcarnitine increased 19.2149-fold, FDR=0.0005) but not in serum and urine in the xenograft model, highlighting a difference between mouse and human. Nonetheless, the data from this study support our earlier data (17) and indicate that human urinary acylcarnitines are excellent proxies of tissue changes, and for this reason could be developed further as potential biomarkers.

Among all measured metabolites, the compound which had the highest magnitude of change was tissue cysteine-glutathione disulfide (CSSG), which was 232.4 times higher in cancer (FDR=0.0005). While also identified in serum, this compound was not significantly changed in that matrix and was below the detection limit in urine. Elevated levels of CSSG and GSSG are a signature of oxidative stress and, in light of the finding of significant changes in CSSG, GSSG and GSH in the xenograft tissue, implicate the oxidative stress pathway as being important in kidney cancer, as has been reported by others in RCC cell lines in general (18). However, in urine and serum these signature metabolites were below the limit of detection and thus, while an important pathway in cancer, glutathione and the oxidative stress pathways are unlikely capable of being biofluid proxies of tumor tissue events or biomarkers or RCC.

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) belong to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily and are involved in the transcriptional activation of many target genes regulating energy metabolism, adipogenesis, angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and inflammation (19). The PPAR family consists of three subunits (α, β/δ, and γ) that heterodimerize with the retinoic acid receptor (RXR) and bind to DNA to either activate or repress expression of a variety of inflammation-related genes (19). PPAR-α is expressed in many tissues, but it is found at particularly high levels in tissues that require fatty acid oxidation as a source of energy such as liver, kidney, and heart, consistent with its known physiological role (20); its signature was detected in all three matrices in our study. Consistent with our findings that a PPAR-α agonist increases RCC cell growth, administration of the agonist WY-14,643 has been shown to significantly induce proliferation of the breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231(21). It has also been proven that long-term feeding of Wy-14,643 caused a 100% incidence of liver tumors in wild-type mice, whereas PPAR-α-null mice was refractory to the same treatment (22). Other PPAR-α agonists such as chlorinated paraffin (C12), cinnamyl anthranilate, perchloroethylene, and trichloroethylene also caused kidney tumors in rats (23). In accordance with the previous studies, our results parallel effects with a PPAR-α agonist and antagonist. A previous study with humans showed that administration of Wy-14,643 significantly attenuated urinary cinnamoylglycine (9-fold) (11), a finding which is in agreement with our observations concerning this metabolite. Attenuation of the PPAR-α pathway may therefore present a novel therapy in treating not only kidney cancer as evidenced by our data but also other solid tumors.

The metabolites in the tryptophan and nicotinamide pathways were well represented in the tumor tissue and intersect at the metabolite quinolinate. We have regularly observed tryptophan metabolites and an altered tryptophan metabolism pathway in our RCC metabolomics and proteomics studies (1, 7), and other investigators have observed a decrease in serum tryptophan in RCCs of all grades (24) similar to we have observed in the present study. In addition to being elevated in mouse tissue and human urine, one of these metabolites, quinolinate, stimulates proliferation of some ccRCC cell lines (1). Perhaps more importantly, IDO, which catalyzes in early step in tryptophan metabolism, regulates conversion of tryptophan to immunosuppressive metabolites which could work to the tumor’s advantage (15). Here we show that inhibition of IDO produces an inflammatory response in ccRCC cell lines, likely by increasing tryptophan metabolites, as evidenced by increased COX2 levels in two RCC cell lines. Thus, the tryptophan metabolites that we have observed in urine and tissue could have mechanistic functions in addition to being potential biomarkers. The mechanism of immune suppression by tryptophan metabolites has been extensively studied in immune cells in pregnancy (25) and to a lesser extent in solid tumors (26). A very recent study in mouse GIST tumors showed that imatinib therapy induced apoptosis within GIST tumors by reducing tumor-cell expression of IDO (15), an event likely associated with decreased immunosuppressive metabolites. Even though our data show that tryptophan metabolism appears to be increased in ccRCC tissue, nicotinamide metabolism is decreased. This could be attributed to utilization of nicotinamide as an electron scavenger (27) and/or to its function to promote cell viability and reduce inflammation (28).

There is always justifiable concern that any study in rodents may have limited applicability to human medicine. We have tried to mitigate these concerns in several ways. Most importantly, our xenograft model is based on subcapsular implantation of a human RCC cell line; such placement recapitulates the anatomy of the human tumor and would be expected to have similar access to blood and urine as would occur in RCC patients. In addition, the control animals were subjected to sham surgery and kidneys from these animals, rather than contralateral kidneys from the cancer animals, were used as controls in order to minimize systemic tumor effects that would likely be seen in the contralateral tissue. For the metabolomics analyses, we have utilized identical platforms as was used in our previous studies in human urine (1, 2) allowing relationships to be accurately made between species.

In summary, this study represents for the first time a comprehensive metabolomics evaluation of cancer, including tumor tissue as well as the 2 most significant and commonly accessed biofluids, serum and urine. Data presented here demonstrate that, not unexpectedly, in kidney cancer blood is a better proxy for tumoral changes than is urine. Furthermore, we have used pathway and network analysis to discover and validate several important metabolic processes which may result in the discovery of novel diagnostic targets and therapeutic approaches for ccRCC.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants 5UO1CA86402 (Early Detection Research Network), 1R01CA135401-01A1, and 1R01DK082690-01A1, and the Medical Service of the US Department of Veterans’ Affairs (all to R.H.W.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ccRCC

(clear cell) renal cell carcinoma

- GC-MS

gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- CSSG

cysteine-glutathione disulfide

- IDO

indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

- 1-MT

1-methyltryptophan

- FDR

false discovery rate

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Reference List

- (1).Kim K, Taylor SL, Ganti S, Guo L, Osier MV, Weiss RH. Urine Metabolomic Analysis Identifies Potential Biomarkers and Pathogenic Pathways in Kidney Cancer. OMICS. 2011;15:293–303. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kim K, Aronov P, Zakharkin SO, Anderson D, Perroud B, Thompson IM, et al. Urine metabolomics analysis for kidney cancer detection and biomarker discovery. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:558–70. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800165-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Sreekumar A, Poisson LM, Rajendiran TM, Khan AP, Cao Q, Yu J, et al. Metabolomic profiles delineate potential role for sarcosine in prostate cancer progression. Nature. 2009;457:910–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- (4).Bathe OF, Shaykhutdinov R, Kopciuk K, Weljie AM, McKay A, Sutherland FR, et al. Feasibility of identifying pancreatic cancer based on serum metabolomics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:140–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Weiss RH, Kim K. Metabolomics in the study of kidney diseases. Nat Rev Nephrology. 2011;8:22–33. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Perroud B, Lee J, Valkova N, Dhirapong A, Lin PY, Fiehn O, et al. Pathway analysis of kidney cancer using proteomics and metabolic profiling. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Perroud B, Ishimaru T, Borowsky AD, Weiss RH. Grade-dependent proteomics characterization of kidney cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;8:971–85. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800252-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Inoue H, Hwang SH, Wecksler AT, Hammock BD, Weiss RH. Sorafenib attenuates p21 in kidney cancer cells and augments cell death in combination with DNA-damaging chemotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011:12. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.9.17680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Evans AM, DeHaven CD, Barrett T, Mitchell M, Milgram E. Integrated, nontargeted ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry platform for the identification and relative quantification of the small-molecule complement of biological systems. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6656–67. doi: 10.1021/ac901536h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Shin M, Ohnishi M, Iguchi S, Sano K, Umezawa C. Peroxisome-proliferator regulates key enzymes of the tryptophan-NAD+ pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;158:71–80. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhen Y, Krausz KW, Chen C, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ. Metabolomic and genetic analysis of biomarkers for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha expression and activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2136–51. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Tachibana K, Anzai N, Ueda C, Katayama T, Kirino T, Takahashi R, et al. Analysis of PPAR alpha function in human kidney cell line using siRNA. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2006:257–8. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrl128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ohta T, Masutomi N, Tsutsui N, Sakairi T, Mitchell M, Milburn MV, et al. Untargeted metabolomic profiling as an evaluative tool of fenofibrate-induced toxicology in Fischer 344 male rats. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37:521–35. doi: 10.1177/0192623309336152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Opitz CA, Litzenburger UM, Opitz U, Sahm F, Ochs K, Lutz C, et al. The indoleamine-2,3- dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitor 1-methyl-D-tryptophan upregulates IDO1 in human cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Balachandran VP, Cavnar MJ, Zeng S, Bamboat ZM, Ocuin LM, Obaid H, et al. Imatinib potentiates antitumor T cell responses in gastrointestinal stromal tumor through the inhibition of Ido. Nat Med. 2011;17:1094–100. doi: 10.1038/nm.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Tafani M, Di VM, Frati A, Pellegrini L, De SE, Sette G, et al. Pro-inflammatory gene expression in solid glioblastoma microenvironment and in hypoxic stem cells from human glioblastoma. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ganti S, Taylor S, Kim K, Hoppel CL, Guo L, Yang J, et al. Urinary acylcarnitines are altered in kidney cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ijc.26274. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Tew KD, Monks A, Barone L, Rosser D, Akerman G, Montali JA, et al. Glutathione-associated enzymes in the human cell lines of the National Cancer Institute Drug Screening Program. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:149–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Pyper SR, Viswakarma N, Yu S, Reddy JK. PPARalpha: energy combustion, hypolipidemia, inflammation and cancer. Nucl Recept Signal. 2010;8:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauca M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137:354–66. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Conzen SD. Minireview: nuclear receptors and breast cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2215–28. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Peters JM, Cattley RC, Gonzalez FJ. Role of PPAR alpha in the mechanism of action of the nongenotoxic carcinogen and peroxisome proliferator Wy-14,643. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:2029–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.11.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Klaunig JE, Babich MA, Baetcke KP, Cook JC, Corton JC, David RM, et al. PPARalpha agonist- induced rodent tumors: modes of action and human relevance. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2003;33:655–780. doi: 10.1080/713608372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lin L, Huang Z, Gao Y, Yan X, Xing J, Hang W. LC-MS based serum metabonomic analysis for renal cell carcinoma diagnosis, staging, and biomarker discovery. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1396–405. doi: 10.1021/pr101161u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Munn DH, Zhou M, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Conway SJ, Marshall B, et al. Prevention of allogeneic fetal rejection by tryptophan catabolism. Science. 1998;281:1191–3. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Uyttenhove C, Pilotte L, Theate I, Stroobant V, Colau D, Parmentier N, et al. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase. Nat Med. 2003;9:1269–74. doi: 10.1038/nm934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:1446–54. doi: 10.2337/db08-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Galli M, Van GF, Rongvaux A, Andris F, Leo O. The nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase: a molecular link between metabolism, inflammation, and cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.