Abstract

Objective: This pilot study tested the feasibility and impact of using mobile media devices to present peer health messages to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients. Subjects and Methods: A convenience sample of 30 adult patients from an outpatient HIV clinic serving a mostly rural catchment area in central Virginia volunteered for the study. Participants viewed short videos of people discussing HIV health topics on an Apple (Cupertino, CA) iPod® touch® mobile device. Pre- and post-intervention surveys assessed attitudes related to engagement in care and disease disclosure. Results: Participants found delivery of health information by the mobile device acceptable in a clinic setting. They used the technology without difficulty. Participants reported satisfaction with and future interest in viewing such videos after using the mobile devices. The majority of participants used the device to access more videos than requested, and many reported the videos “hit home.” There were no significant changes in participant perceptions about engagement in care or HIV disclosure after the intervention. Conclusions: This pilot study demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability of using mobile media technology to deliver peer health messages. Future research should explore how to best use mobile media to improve engagement in care and reduce perceptions of stigma.

Key words: human immunodeficiency virus, mobile media, peer health messages

Introduction

Mobile technologies are increasingly supplementing traditional healthcare services. The integration of healthcare with mobile phones and other mobile devices, known as m-health, has the potential to create efficiencies, expand services, and enhance patient–provider communications in clinical environments and beyond.1 In a system where patient time with providers is limited, m-health devices efficiently deliver and reinforce health messages.

m-Health may have particular relevance in the treatment of chronic diseases. Effective chronic disease management challenges both patients and providers.2 Patients with one or more chronic disease(s) must adhere to complex treatment regimens to control symptoms and to reduce future morbidity and mortality.3 Research has demonstrated successful applications of m-health in several chronic care settings, including diabetes4 and asthma.5

People living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (PLWH) and their providers implement one of the most challenging chronic care treatment plans.2,6 For populations living with HIV in the rural southern United States, barriers to care include confidentiality,7 stigma,8,9 and inequality.10–12 These populations suffer from increased social isolation,13 heightened risk of depression,14 and inadequate access to quality healthcare.15,16 However, there is emerging evidence that m-health interventions can help overcome both personal and systemic barriers.17,18 Using m-health interventions in HIV disease management facilitates the presentation of health messages in acceptable and user-friendly means. Personal digital assistants,19 short message service or text messages,20 and mobile phones21,22 are several devices showing evidence of feasibility and promise among PLWH.

Peer-to-peer sharing of HIV-specific experiences has proven successful for HIV prevention in high-risk populations23–25 and for coping with grief in individuals living with the disease.26 Given that patient attitudes and beliefs related to social support affect HIV medication adherence,8,27,28 we posited that they might be influenced by peer messages. Moreover, we wanted to explore whether using mobile media devices to deliver peer health messages would be feasible in a busy clinic setting. Therefore, this study explored the feasibility and potential impact of providing peer health messages using mobile technology in an academic medical center's HIV clinic serving a primarily rural southern U.S. patient population.

Subjects and Methods

The setting for the study was the University of Virginia Health System Infectious Disease Clinic in Charlottesville, VA. The clinic serves a semirural to rural population of approximately 650 HIV-positive patients from a large geographic area in central Virginia. A convenience sample of patients volunteered to complete the study during normal clinic hours. Participants completed the baseline survey, m-health intervention, and follow-up survey in the course of one clinic session. The University of Virginia Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Participants

Participants enrolled between November 2009 and February 2010. Eligibility criteria included being 18 years or older, having a confirmed diagnosis of HIV, and English proficiency. A brief overview of the project was presented to eligible participants; those who expressed interest provided written informed consent. Patients presenting for an initial clinic visit were not approached for participation. Participants received a $10 gift card upon study completion as compensation for their time.

Measures

Participants completed baseline surveys, which measured demographic characteristics, availability of Internet access, frequency of Internet use, residential environment, and years living with HIV. In addition, 11 survey items assessed baseline attitudes on engagement in HIV care and comfort with HIV disclosure. Follow-up surveys contained identical items supplemented by questions on the acceptability of, satisfaction with, and future interest in the video messages they had viewed. All items were rated using a Likert scale of 1 (“disagree”) to 5 (“agree”).

Intervention

After participants completed baseline surveys, a research team member presented brief instructions on how to navigate an Apple (Cupertino, CA) iPod® touch® preprogrammed with peer health videos. ThePositiveProject.org, an organization committed “to us[ing] the stories of people infected and affected by HIV/AIDS to raise awareness, reduce stigma, promote prevention, encourage testing, and enhance care and quality of life,” supplied peer health messages. Study participants were instructed to watch at least 2 and as many of the 40 videos as they wished. Participants indicated when they had finished watching the videos. Immediately following this, participants completed follow-up surveys.

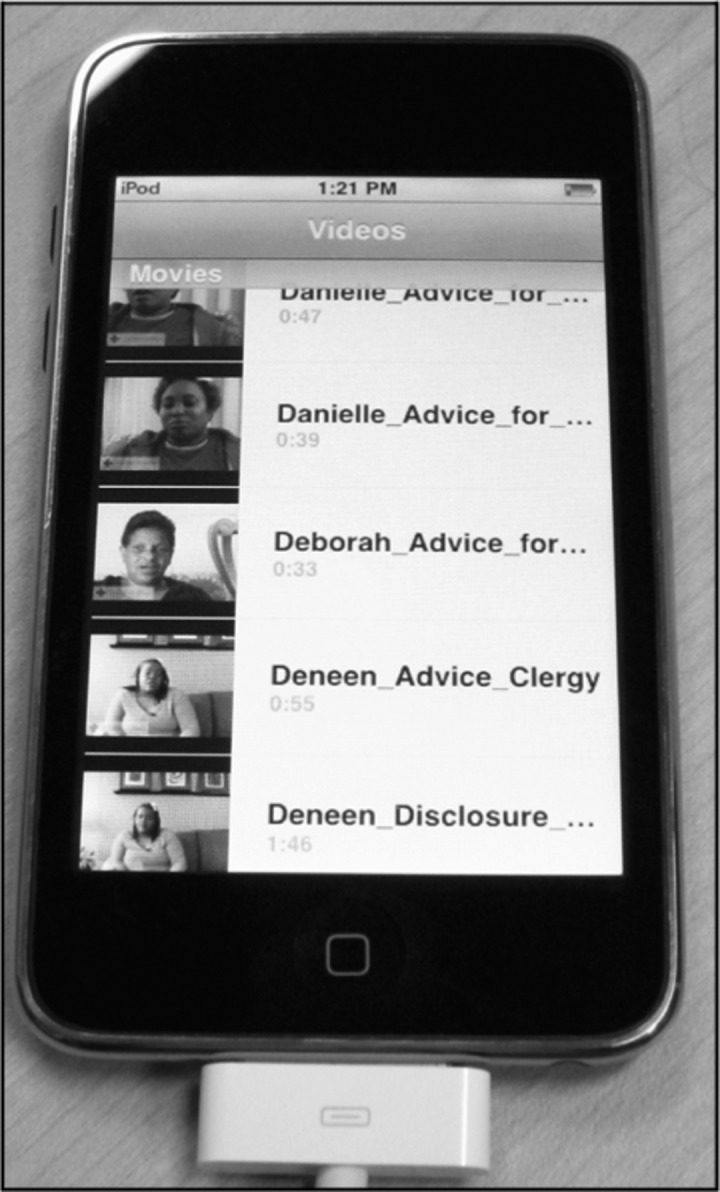

The video intervention was presented on a second-generation Apple iPod touch (110×61.8×8.5 mm, 89 mm multi-touch color display, weighing 115 g, 8GB, iPod touch version 3.1 software, with battery for 6 h of video) (Fig. 1). Videos ranged in length from 23 to 131 s; all 40 videos had a total running time of approximately 37 min. Individual videos display a person infected with HIV speaking on a specific issue related to their health (Fig. 2). Forty videos of the 1,400 available at the time were downloaded from the Web site onto the Apple iPod touch using Apple iTunes® software. Videos were selected to cover topics including stigma, HIV medication adherence, and disclosure. Speakers in videos were also selected to vary by age, gender, and ethnicity. Titles and pictures on the device's menu screen aided participants in selecting which videos to watch.

Fig. 1.

An iPod touch with video menu display.

Fig. 2.

Display of an iPod touch with ThePositiveProject.org video narrative.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed with SPSS version 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics characterized the participant population, and paired-sample t tests analyzed participant attitudes towards engagement in medical care and disease disclosure, comparing baseline and follow-up responses. The reliability of scales was tested with Cronbach's α. Scaled scores, combining three items each, were created to measure engagement in HIV care. Follow-up survey items were analyzed for participants' perceptions of the study intervention.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Thirty participants completed the study (Table 1). The majority were male (n=18, 60%), while most were between the ages of 41 and 50 years (n=16, 53%) and were living in a small town or more rural area (n=21, 70%). The mean time since HIV diagnosis was 11 years, while the range of time living with HIV was 1–23 years (SD=6.54). Study participants reflected the demographics of the clinic patient population. Most participants had over 5 days of Internet access per week (n=21, 70%), but a noteworthy minority had between 0 and 2 days of access (n=9, 30%).

Table 1.

Population Demographics

| POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 18–30 | 1 (3) |

| 31–40 | 4 (13) |

| 41–50 | 16 (53) |

| 51+ | 9 (30) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 18 (60) |

| Female | 11 (37) |

| Transgender | 1 (3) |

| Living situation | |

| Farm to small town | 21 (70) |

| Medium city | 8 (27) |

| Large city | 1 (3) |

| Days of Internet access per week | |

| 0–2 | 9 (30) |

| 3–4 | — |

| 5–7 | 21 (70) |

Feasibility

The mean number of videos watched was 10.7 with a range of 2–40 (SD=7.98). The mean length of time for the intervention including survey completion was 38.4 min with a range of 12–162 min (SD=29.59). For several of the participants, scheduled medical appointments interrupted the study. In those cases, time spent with the provider was included in the time of the intervention. Participants completed the study in various locations throughout the clinic, including 10 (33%) in clinic examination rooms, 10 (33%) in the clinic anteroom, and 6 (20%) in the clinic waiting room. Many participants changed location, carrying the device to their next clinic activity. Even though the majority of participants reported no previous use with the mobile media device, all participants were observed independently operating the iPod touch.

Acceptability

Participants' interest in viewing the videos was high (Fig. 3). The majority (n=21, 70%) of patients reported that the videos were somewhat to very “helpful and meaningful,” and 22 (73%) were interested in viewing more videos. Eighteen (60%) participants reported that the videos made clinic visits more enjoyable, but only half reported that the video messages made them feel stronger or made them more committed to attend clinic.

Fig. 3.

Post-intervention participant evaluation.

Impact on Attitudes

Survey items were combined to create scaled scores to measure engagement in HIV care (Cronbach's α values at baseline=0.76, follow-up=0.53) and comfort with HIV disclosure (α value baseline=0.82, follow-up=0.74). At baseline participants reported positive attitudes (mean of 4.2 out of 5) towards engagement in care but scored neutrally on HIV disclosure (Table 2). There were no statistically significant changes between baseline and follow-up attitudes for separate items or for scaled scores.

Table 2.

Survey Item Means and Paired-Sample t Tests

| SURVEY ITEMS AND SCALED SCORES | BASELINE MEAN | FOLLOW-UP MEAN | PAIRED-SAMPLE T TEST | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “I look for information on my diagnosis to learn more.” | 3.93 | 4.23 | −1.06 | 0.30 |

| “I feel alone.” | 2.73 | 2.90 | −0.87 | 0.39 |

| “I am not motivated to come to clinic.” | 1.55 | 1.83 | −1.25 | 0.22 |

| “I take my medicine regularly and on time.” | 4.25 | 4.29 | −0.16 | 0.88 |

| “I felt that my story could be supportive to others.” | 3.83 | 3.70 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| “I am comfortable talking to my doctors and nurses.” | 4.43 | 4.60 | −0.71 | 0.48 |

| “I am embarrassed of my diagnosis.” | 2.43 | 2.70 | −1.49 | 0.15 |

| “I feel emotionally drained.” | 3.23 | 3.00 | 1.19 | 0.24 |

| “I feel I have support for my HIV.” | 3.86 | 4.17 | −1.61 | 0.12 |

| “I feel that I must hide my diagnosis from others.” | 3.24 | 3.00 | 0.91 | 0.37 |

| “I am open to telling people about my HIV.” | 2.63 | 2.43 | 1.24 | 0.23 |

| Combined medical engagement itema | 4.20 | 4.39 | −0.95 | 0.35 |

| Combined disclosure itema | 3.19 | 3.24 | −0.56 | 0.58 |

Items were rated on a Likert scale of 1 ("disagree") to 5 ("agree").

Scaled scores.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Discussion

These preliminary results demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of delivering peer health messages using a mobile device. It is feasible to use a mobile device to deliver an intervention even in a busy clinic environment. The device's mobility allowed participants to watch the intervention videos across the stages of their clinic appointments, taking it with them as they transitioned from the waiting room to exam room. Participant “downtime” waiting for a provider was spent watching the peer health messages. Participants often continued viewing the videos in the clinic waiting room after the completion of their appointment, reflecting their continued interest. Although space is a limited resource in most clinic environments, the mobile device with headphone and speaker capabilities adapted to both participants listening confidentially in a busy area or sharing the videos with accompanying friends and/or family. Additionally, the technical requirements of an iPod user were not a barrier. Even though the majority of participants reported no prior experience with an iPod or other m-health device, after brief instruction, all were successful at independently navigating the intervention. From a logistical standpoint, implementing the mobile device was simple. None of the iPods were stolen or damaged.

The intervention was acceptable and appealing to the participants. Our findings that nearly all participants (n=28, 93%) viewed more than the two required videos and that participants watched a mean of 10.7 videos (SD=7.98; range, 2–40) imply that participants were actively engaged by the intervention. Consistent with watching more than the required number of videos, the majority of participants reported enjoyment and further interest in viewing additional narratives. Qualitatively, many participants reported identifying with the peer health messages (Fig. 4). One participant said, “[the message] hit home, exactly the same thing happened to me.” Another saw parallels in his own life, stating “this could just as easily be me speaking on this video.” One participant observed the benefits of the mobile media intervention “as a support group, [where] we can meet other people.”

Fig. 4.

Representative responses to peer health messages.

Limitations

This sample was a convenience sample of clinic patients attending regular appointments who may not represent the full range of patients in this clinic or HIV patients as a larger group. Because of the pilot nature of this exploratory study, the sample size was too small and the intervention too short to expect to detect changes in attitudes on treatment engagement or HIV disclosure. In addition, it is possible that a ceiling effect limited our ability to detect a change in participant attitudes because of the relatively positive attitude about HIV care endorsed by the participants at baseline. It is not surprising that participants, many of whom have been living with HIV for over 10 years, did not change their attitudes given that the length of time between measurements (baseline survey to follow-up survey) was generally minutes.

Conclusions

Rapidly evolving technology in the form of smart phones, tablets, and increasing access to Internet connections creates new opportunities for personal tailoring of health messages that can respond to patients' current interests. Moreover, it is important to explore which delivery methods appeal to different patient groups. This pilot study demonstrated that typical HIV clinic patients representing a semirural population have the capacity to use mobile technology even with minimal prior exposure and provider supervision. The results of this study show that using mobile media devices to present peer health messages to PLWH in a clinic setting is acceptable, feasible, and practical in a busy clinic with limited space, time, and privacy. This has implications for other HIV clinic settings seeking to add patient interventions or research studies without disrupting the clinic work flow or compromising confidentiality. In such cases, the intervention or study requires maximum flexibility, mobility, and brevity. The size and portability of the mobile media device meet these criteria. In addition, for patients who have not disclosed their HIV serostatus to family members or peers, this intervention offers a novel means to assess quality peer advice and experiences that may be superior to unfiltered or unreviewed content on the Internet. Finally, we believe that the peer health videos may enhance, supplement, and reinforce provider-delivered messages about HIV, self-care, adherence, and other relevant topics.

Future research should determine the potential of using technology-based delivery methods, and of delivering peer health messages, to enhance patient engagement in HIV care within the clinic environment. Although many m-health interventions are based outside the clinic setting and use patient mobile phones, the full range of technological methods of delivering interventions should be explored, as should their potential to become integrated within clinic visits to supplement clinician-delivered care. m-Health interventions may have a significant role in improving HIV care outcomes, especially for more rural or isolated subpopulations of patients. This style of intervention may also have great utility and impact by reducing stigma and increasing engagement in care for those with a lapse in their care or who are newly diagnosed.

Acknowledgments

Funding for effort of the Principal Investigator, R.D., was provided by grant K23 AI77339 and for K.I. by grant RO1 DA016554. Videos were provided by The Positive Project. We thank the University of Virginia Infectious Disease Clinic patients and staff who facilitated the implementation of this study, especially Karman Rodrigues-Torres and Bruce Ellsworth. We thank Barbara Winstead and Valerian Derlega of Old Dominion University for editorial assistance.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lester RT. van der Kop M. Taylor D. Alasaly K. m-Health: Connecting patients to improve population and public health. BCMJ. 2011;53:218. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giordano TP. Gifford AL. White AC. Suarez-Almazor ME. Rabeneck L. Hartman C. Backus LI. Mole LA. Morgan RO. Retention in care: A challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swendeman D. Ingram B. Rotheram-Borus MJ. Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: An integrative framework. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1321–1334. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrer-Roca O. Cardenas A. Diaz-Cardama A. Pulido P. Mobile phone text messaging in the management of diabetes. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10:282–285. doi: 10.1258/1357633042026341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strandbygaard U. Thomsen SF. Backer V. A daily SMS reminder increases adherence to asthma treatment: A three-month follow-up study. Respir Med. 2010;104:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simoni JM. Frick PA. Pantalone DW. Turner BJ. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: A review of current literature and ongoing studies. Top HIV Med. 2003;11:185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson J. Rural HIV/AIDS in the United States: Studies suggest presence, no rampant spread. JAMA. 2000;284:167–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golin C. Isasi F. Bontempi JB. Eng E. Secret pills: HIV-positive patients' experiences taking antiretroviral therapy in North Carolina. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:318–329. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.5.318.23870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowshen N. Binns HJ. Garofalo R. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:371–376. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mugavero MJ. Lin HY. Allison JJ. Giordano TP. Willig JH. Raper JL. Wray NP. Cole SR. Schumacher JE. Davies S. Saag MS. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: Do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olatosi BA. Probst JC. Stoskopf CH. Martin AB. Duffus WA. Patterns of engagement in care by HIV-positive adults: South Carolina, 2004–2006. AIDS. 2009;23:725–730. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328326f546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reif S. Geonnotti K. Whetten K. HIV infection and AIDS in the Deep South. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:970–973. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart K. Cianfrini L. Walker JF. Stress, social support and housing are related to health status among HIV-positive persons in the Deep South of the United States. AIDS Care. 2005;17:350–358. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331299780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uphold CR. Rane D. Reid K. Tomar SL. Mental health differences between rural and urban men living with HIV infection in various age groups. J Community Health. 2005;30:355–375. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-5517-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutton M. Anthony MN. Vila C. McLellan-Lemal E. Weidle PJ. HIV testing and HIV/AIDS treatment services in rural counties in 10 southern states: Service provider perspectives. J Rural Health. 2010;26:240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reif S. Golin CE. Smith SR. Barriers to accessing HIV/AIDS care in North Carolina: Rural and urban differences. AIDS Care. 2005;17:558–565. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy H. Kumar V. Doros G. Farmer E. Drainoni ML. Rybin D. Myung D. Jackson J. Backman E. Stanic A. Skolnik P. Randomized controlled trial of a personalized cellular phone reminder system to enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:153–161. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang X. Wang Q. Yang X. Cao J. Chen J. Mo X. Huang J. Wang L. Gu D. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: A meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brock TP. Smith SR. Using digital videos displayed on personal digital assistants (PDAs) to enhance patient education in clinical settings. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76:829–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lester RT. Mills EJ. Kariri A. Ritvo P. Chung M. Jack W. Habyarumana J. Karanja S. Barasa S. Nquti R. Estambale B. Ngugi E. Ball T. Thabane L. Kimani J. Gelmon L. Ackers M. Plummer F. The HAART cell phone adherence trial (WelTel Kenya1): A randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials. 2009;10:87. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curioso WH. Kurth AE. Access, use and perceptions regarding Internet, cell phones and PDAs as a means for health promotion for people living with HIV in Peru. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lester RT. Karanja S. Mobile phones: Exceptional tools for HIV/AIDS, health, and crisis management. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:738–739. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broadhead RS. Heckathorn DD. Weakliem DL. Anthony D. Madray H. Mills R. Hughes J. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: Results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Rep. 1998;113:42–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grinstead O. Zack B. Faigeles B. Reducing postrelease risk behavior among HIV seropositive prison inmates: The health promotion program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13:109–119. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.2.109.19737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin SS. O'Connell DJ. Inciardi JA. Surratt HL. Maiden KM. Integrating an HIV/HCV brief intervention in prisoner reentry: Results of a multisite prospective study. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:427–436. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sikkema KJ. Hansen NB. Kochman A. Tate DC. Difranceisco W. Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a group intervention for HIV positive men and women coping with AIDS-related loss and bereavement. Death Stud. 2004;28:187–209. doi: 10.1080/07481180490276544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remien RH. Hirky AE. Johnson MO. Weinhardt LS. Whittier D. Le GM. Adherence to medication treatment: A qualitative study of facilitators and barriers among a diverse sample of HIV+ men and women in four US cities. AIDS Behav. 2003;7:61–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1022513507669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beach MC. Keruly J. Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]