Abstract

The cause of biliary atresia (BA) is unknown and in the past few decades the majority of investigations related to pathogenesis have centered on virus infections and immunity. The acquired or perinatal form of BA entails a progressive, inflammatory injury of bile ducts, leading to fibrosis and obliteration of both the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts. Theories of pathogenesis include viral infection, chronic inflammatory or autoimmune-mediated bile duct injury and abnormalities in bile duct development. This review will focus solely on human studies pertaining to a potential viral trigger of bile duct injury at diagnosis and provide insight into the interplay of the innate and adaptive immune responses in the pathogenesis of disease.

Keywords: biliary atresia, adaptive immunity, Innate immunity, neonatal cholestasis

Introduction

Biliary atresia (BA) is a bewildering cause of neonatal cholestasis, occurring in approximately 1 out of 10,000–15,000 live births in the United States. Broadly, there are thought to be two forms of BA - the acquired/perinatal form and the embryonic/congenital form. The rarer embryonic form is associated with other congenital anomalies including, but not limited to, polysplenia and situs inversus. Greater than 80% of patients with BA are of the acquired/perinatal form and it is this form of BA that will be discussed in this review. The acquired/perinatal form of BA entails a progressive, inflammatory injury of bile ducts, leading to fibrosis and obliteration of both the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts.[1, 2] Despite surgical intervention with the Kasai portoenterostomy, the intrahepatic bile duct injury progresses, leading to biliary cirrhosis in the majority of children. Therefore, BA is the indication for greater than 50% of all pediatric liver transplants. Only 15–20% of children with BA will enter adulthood with their native liver and the majority of those patients will have evidence of chronic liver disease or cirrhosis.[3]

The etiology of BA is unknown and theories of pathogenesis include viral infection, chronic inflammatory or autoimmune-mediated bile duct injury and abnormalities in bile duct development.[1, 2, 4, 5] A recent study identified mild direct hyperbilirubinemia in BA patients at birth (1.4 ± 0.43 mg/dL) compared to normal infants (0.19 ± 0.43).[6] This suggests that the initiation of biliary injury in BA has begun prior to birth. One theory to explain this would be an in utero cholangiotropic virus infection, most likely late in the third trimester. A leading hypothesis in the pathogenesis of BA is that the bile duct injury is initiated by a virus infection followed by an exaggerated inflammatory or autoimmune response targeting bile duct epithelia, resulting in progressive bile duct damage and obliteration. This review will focus on human studies (PubMed search) pertaining to a potential viral trigger of bile duct injury at diagnosis and provide insight into the interplay of the innate and adaptive immune responses in the pathogenesis of disease.

Perinatal Virus Infection and Biliary Atresia

In 1974, Benjamin Landing first proposed that BA and other infantile obstructive cholangiopathies were caused by viral infection of the liver and hepatobiliary tree.[7] This theory has been supported by the recent observation that the innate immune response in BA at diagnosis is similar to that seen with viral infections, with up regulation of MxA proteins and Toll-like receptors 3 and 7 (detailed below under innate immunity).[8–10] Candidate viruses that may trigger the bile duct injury include human papillomavirus,[11] Epstein-Barr virus,[12] cytomegalovirus (CMV),[13, 14] rotavirus,[15] and reovirus.[16] The majority of the investigations pertaining to infection and BA have concentrated on reovirus, rotavirus, and CMV.

Reovirus

Many groups have examined liver and bile duct tissue for reovirus nucleic acids using RT-PCR. Tyler et al.[16] found reovirus L1 gene amplification products in frozen liver and biliary tissues from 11 out of 20 (55%) patients with BA. Steele et al.[17] however, did not detect reovirus RNA in formalin fixed liver tissue from 14 BA patients using nested primers specific to the M3 gene segment of reovirus serotype 3. Technical differences that may have contributed to the opposing results found in these two studies include the fixation method of tissue analyzed (frozen versus formalin-fixed) and the reoviral genome segment analyzed (L1 versus M3). Most recently, Rauschenfels et al.[10] utilized nested primers specific to the L3 gene segment of reovirus and found evidence of this in 21 out of 64 (33%) BA samples.

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is also a dsRNA virus of the Reoviridae family. Like reovirus, this virus has been shown to infect hepatocytes as well as bile duct epithelia.[18] Riepenhoff-Talty et al.[15] detected group C rotavirus RNA in 50% of infant BA liver specimens and none of other cholestatic disease controls. By comparison, Bobo et al.[19] did not detect rotavirus (groups A, B or C) RNA from infant BA liver specimens or controls. A more recent study by Lin et al.[20] found a significant decrease in the incidence of BA in Taiwan following introduction of a rotavirus vaccination. The authors proposed that although rotavirus vaccination is initiated at 2 months of age, later than the usual age of onset of BA, herd immunity might have decreases rotavirus infection during pregnancy or the neonatal period. Further longitudinal studies will be necessary to confirm this finding.

Cytomegalovirus

The greatest body of research entails investigations of CMV at the time of diagnosis of BA. CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Herpesviridae family that infects biliary epithelia, as demonstrated by CMV inclusion bodies within the epithelia.[21–23] Fischler’s group from Sweden has shown higher prevalence of CMV antibodies in the mothers of BA infants, higher serum CMV-IgM levels in infants with BA, and greater amounts of immunoglobulin deposits on the canalicular membrane of the hepatocytes in infants with BA with ongoing CMV infection.[14, 24] Subsequent work by this group revealed no difference in long-term survival with regard to early CMV infection. However, this study was limited by a small sample size and larger studies may be needed to detect a difference.[25] In contrast, a Chinese study demonstrated a lower rate of clearance of jaundice, a higher incidence of cholangitis, and a more severe degree of liver fibrosis and inflammation after Kasai in BA infants with a history of perinatal CMV infection, suggesting that CMV infection may correlate with a worse prognosis.[26] Strong evidence for a perinatal CMV infection associated with BA was recently described by Xu et al.[27] Liver tissue obtained at the time of portoenterostomy on 85 infants with BA was analyzed by real-time PCR for the presence of the following viruses: HSV, EBV, VZV, CMV and adenovirus. The majority of the specimens were positive for CMV (51 of 85; 60%) and a few were positive for adenovirus (5/85) and EBV (3/85). Studies confirming the presence of CMV in PCR positive liver samples were performed with immunocytochemical detection of CMV-pp65 antigens within liver bile duct epithelia and hepatocytes.[27]

One could theorize that if the newborn was exposed to low levels of virus in the perinatal period, the neonatal immune system could elicit a Th1 cellular response with production of virus-specific memory T cells that, upon restimulation with virus, would become activated and secrete Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ). Brindley et al.[28] analyzed the liver memory T cell response to a variety of viruses from infants with newly diagnosed BA in order to ascertain if a recent hepatobiliary virus infection had occurred. Liver T cells from BA and control patients were cultured with antigen presenting cells in the presence of a variety of viral proteins including CMV, Epstein-Barr virus, reovirus and rotavirus. Fifty-six percent of BA patients had significant increases in IFN-γ-producing liver T cells in response to CMV homogenate and CMV-pp65 antigen, compared to minimal/no BA responses to other viruses or the control group CMV response. The robust liver T cell memory response to CMV suggested that perinatal CMV infection had occurred and that CMV infection was a plausible initiator of the bile duct damage in BA.

In summary, many viruses have been proposed to cause BA, with the strongest evidence gained from studies involving CMV. However, there continues to be conflicting reports of the detection of virus infection at the time of diagnosis. Discrepancies may be related to techniques used to store tissue (fresh, snap-frozen vs. formalin-fixed), the viral genome segment analyzed and the age of the patient at the time of analysis. Nonetheless, in the studies that identified molecular evidence of a pathogen, reovirus, rotavirus or CMV were found in up to 60% of specimens tested. If one extrapolates from the mouse model data outlined by Claus Petersen (pp XX – XX) in this journal, it is possible that the virus is cleared quickly from the liver in the first few weeks of life, and testing at that time for virus would be negative. An interesting observation from these studies is the ability of all three viruses to infect and damage bile duct epithelia, lending support to a primary cholangiotropic viral infection as the initiating event in the pathogenesis of BA.

Immunology Overview

The innate and adaptive immune responses are intricately intertwined and are separated here only for the convenience of discussing the investigations specific to each arm of immunity. The innate immune system is the first line of defense against pathogens and key players in innate immunity include macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells and neutrophils. Dendritic cells and macrophages link the innate system to adaptive immunity, as they are essential for the execution of adaptive immune responses. Dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells function as professional antigen presenting cells and are responsible for presenting antigens (peptides or proteins) to T cells with subsequent activation. Adaptive immunity entails immune responses that are stimulated by repeat exposure to pathogens or non-microbial antigens. The defining characteristics of adaptive immunity include the fine specificity for distinct molecules and memory that evokes the ability to respond to repeat exposures. There are two types of adaptive immune responses: cellular immunity mediated by T cells with the generation of cytokines, and humoral immunity mediated by B cells that produce antibodies.

Activation of Innate Immunity in Biliary Atresia

The innate immune system responds to infection or irritation by producing a rapid, non-specific inflammation with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6. Cells of the innate immune system possess two major classes of receptors: membrane-bound Toll-like receptors (TLR) and cytosolic nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLR), collectively known as pattern recognition receptors (PRR). [29] Importantly, not only innate immune cells express PRRs, but also bile duct epithelial cells.[30] PRRs recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on infected cells, which are conserved molecular patterns that are invariant among an entire class of pathogens. Examples of PAMPs include bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipoproteins, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and single-stranded viral RNA (ssRNA). Each TLR subtype recognizes and binds to a particular PAMP. For example LPS is detected by TLR4, dsRNA by TLR3 and ssRNA by TLR7/TLR8.[31] It has also been suggested that not only pathogens but also endogenous ligands from necrotic cells can activate TLR signaling, pointing to a possible contribution of TLRs in the development of autoimmunity. [32] PRR-PAMP interactions result in a cascade of inflammatory mediators, leading to pathogen (and sometimes host cell) death. It is plausible that failure to regulate TLR signaling results in a chronic inflammatory disease.

Toll-like receptor signaling has recently been investigated in BA. Saito et al.[33] found upregulation of TLR8 in livers from BA patients at diagnosis compared to controls. Outcome analysis revealed significantly increased levels of hepatic TLR3 and TLR7 at diagnosis in those BA patients who required transplant (versus no transplant). Interestingly, all of the identified TLRs are receptors for either dsRNA or ssRNA (virus components). Huang et al.[9] also analyzed hepatic RNA from BA patients at diagnosis and found increased levels of TLR7 compared to choledochal cyst controls. Immunohistochemistry analysis revealed strong expression of TLR7 in bile duct epithelia, Kupffer cells and neutrophils. Based on the fact that TLR7 is the receptor for ssRNA viruses and subsequently activates type 1 interferons through the signaling molecule MxA, analysis of MxA levels also revealed significant increases in BA samples compared to controls, suggesting stimulation of type 1 interferons.[9] Harada et al.[34] demonstrated that bile duct epithelial cells from BA patients expressed TLR 3, which is able to recognize viral dsRNA, such as reovirus. When the bile epithelial cells were stimulated by a synthetic analog of viral dsRNA, [poly(I:C)], they produced MxA and interferon-β1, up-regulated tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression, and induced biliary apoptosis. Thus, bile duct epithelial cells appear to play an active role in stimulating innate immunity through the dsRNA virus-TLR3 pathway, generating an apoptotic response that leads to obstructive cholangiopathy.

As mentioned above, macrophages are part of both innate and adaptive immune responses. Many investigators have identified increased numbers of macrophages/Kupffer cells in BA at the time of diagnosis.[35–39] Urushihara et al.[36] identified significantly increased number and size of Kupffer cells in the liver and increased levels of serum IL-18. IL-18 (IFN-γ–inducing factor) is a macrophage-derived cytokine that works in concert with IL-12 to promote Th1 cell differentiation in the inflammatory setting (discussed below under adaptive immunity). Our group also described significant increases in the number and size of macrophages infiltrating the portal tracts in BA and showed that these cells produced high levels of TNF-α.[39] In addition, marked CD68+ macrophage infiltrates in the portal tracts correlated with a worse outcome in BA patients.[37] Other areas of innate immunity research in BA have focused on identifying polymorphisms of macrophage-associated genes that could result in altered macrophage function. Genomic DNA analysis from 90 BA patients identified significantly increased frequencies of T allele and T/T homozygosity of the CD14/-159 promoter polymorphism. The T/T homozygote has been associated with increased expression of CD14 in monocytes. CD14 is a macrophage cell surface glycoprotein that recognizes endotoxin (LPS) and activates TNF-α. CD14 has also been found to be important in controlling virus infections.[40] This study also found that the promoter polymorphism correlated with depressed levels of plasma soluble CD14 (sCD14) and poorer outcome. Circulating sCD14 is an important mediator in neutralizing LPS. The authors concluded that exaggerated activation of macrophages through CD14 promoter polymorphisms resulted in excess stimulation of innate immunity and contributed to bile duct damage. A study from Turkey showed an increased frequency of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)-173C allele in BA patients compared to controls.[41] MIF is a pleiotrophic lymphocyte and macrophage cytokine that plays an important role in innate immunity. Promoter polymorphisms of the MIF gene have been associated with over-production of MIF and increased susceptibility to chronic inflammatory diseases.[42, 43]

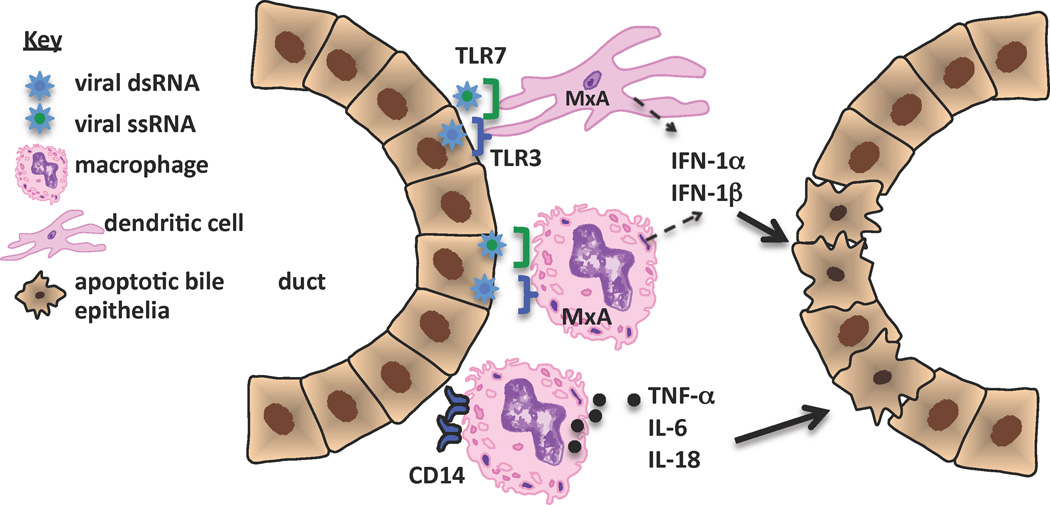

To date, the investigations into the workings of innate immunity in BA suggest a sustained induction of the innate response, without the development of tolerance, resulting in chronic inflammation and destruction of bile duct epithelia.[44] The contribution of innate immune responses to bile duct injury in BA, based on the literature presented in this review is outlined in Figure 1. There is a paucity of research on the role of dendritic cells, NK cells and neutrophils in human BA and should be the focus of future research efforts.

Figure 1. Contribution of innate immune responses to bile duct injury in biliary atresia.

This figure summarizes human investigations to date that pertain to innate immunity in BA. Virus infection of bile duct epithelia activates TLRs on dendritic cells, macrophages and bile duct epithelia (not shown), leading to upregulation of MxA transcription factor and downstream stimulation of type 1 interferons (IFN). Concurrently, macrophages are activated, with increased expression of CD14 and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Both type 1 IFNs and inflammatory cytokines play a direct role in bile duct epithelial injury and apoptosis. It is theorized that a sustained induction of the innate response, without the development of tolerance, could explain the chronic inflammation and bile duct destruction found in BA.

Evidence for Dysregulation of Adaptive Immunity in Biliary Atresia

Cellular Immunity

The predominant cellular immune response in BA at diagnosis encompasses activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within portal tracts that produce Th1 cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ) and macrophages secreting TNF-α[38, 39, 45–47] These lymphocytes have been found invading between bile duct epithelia, leading to degeneration of intrahepatic bile ducts.[48] The T cells are highly activated, expressing the proliferation cell surface marker CD71 and activation markers CD25 and LFA-1.[38] In addition, the T cells displayed increased expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3, which binds ligands that support Th1 cellular differentiation.[47] Analysis of the T cell receptor variable region of the β-chain (TCR Vβ) within BA liver and extrahepatic bile duct remnants revealed that the T cells were oligoclonal in nature, with a limited TCR Vβ repertoire, suggesting antigen-specific activation. The CD4+ TCR expansions were limited to Vβ3, 5, 9 and 12 T cell subsets and the CD8+ TCR Vβ expansions were predominantly Vβ20. The oligoclonal expansions suggest that the T cells in BA are proliferating in response to a specific antigen(s) such as viral proteins or “self” bile duct epithelial proteins.[49]

Cytokine production and activity is usually localized within the target organ, however with increased severity of inflammation and cytokine production, the cytokines may enter the circulation and can be detected within the sera or plasma. Narayanaswamy et al.[50] performed a thorough analysis of plasma Th1(IL-2, IFN-γ), Th2 (IL-4, IL-10), and macrophage (IL-18, TNF-α) cytokines and adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, with the goal of identifying plasma biomarkers of disease. Plasma levels were assessed at the time of Kasai and serially thereafter for 6 months. All cytokines (except IL-10) and adhesion molecules increased over the 6 month period, suggesting that the inflammatory process is progressive and not ameliorated by portoenterostomy. Importantly, sICAM-1 was identified as a probable biomarker of disease severity, as plasma sICAM-1 correlated positively with serum bilirubin and a high sICAM-1 level predicted need for transplantation in the first year of life. Importantly, ICAM-1 expression has previously been shown to be upregulated within BA liver tissue[51] and a recent study from Egypt identified elevated sICAM-1 levels in BA patients compared to controls.[52] In addition, analysis of polymorphisms of the ICAM-1 gene in BA discovered that the ICAM G241R polymorphism was significantly associated with BA, suggesting that this polymorphism plays a role in disease pathogenesis.[53] ICAM-1 is an adhesion molecule that is expressed on cells of multiple lineages at sites of inflammation and mediates leukocyte and granulocyte migration through endothelial cells as well as promotes antigen-specific T cell proliferation. Serum cytokine analysis has also been performed in older BA patients (median 9 years of age), where significant elevations in serum IL-18 and IFN-γ in BA patients were identified, with IL-18 levels correlating with severity of jaundice.[54] As mentioned above, IL-18 (produced by macrophages) works in concert with IL-12 to promote Th1 cell differentiation and therefore IFN-γ production.

Bezerra et al.[45] utilizing gene expression microarray techniques to analyze BA liver biopsies, observed upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes including IFN-γ and osteopontin. Osteopontin is a Th1 cytokine that is secreted by a variety of cell types and plays a key role in immune cell recruitment to sites of inflammation as well as extracellular matrix formation and fibrosis. Whitington et al.[55] showed increased levels of osteopontin in BA liver tissue that localized to bile duct epithelia and correlated with bile duct proliferation and fibrosis. These finding were reproduced by Huang et al.[9], whereby osteopontin expression localized to bile duct epithelia and positively correlated with severity of fibrosis by trichrome stain in BA livers at diagnosis. In addition, a positive correlation was identified between osteopontin and both NF-κB (upstream transcription factor activating osteopontin) and TGF-β downstream effector molecule associated with fibrosis). The upregulation of osteopontin persists in BA, as older BA patients (mean age 8.2 years) also had significantly increased levels of plasma osteopontin compared to controls, with the BA patients with persistent jaundice or portal hypertension expressing the highest levels of osteopontin.[56]

Cellular Autoimmunity in Biliary Atresia

A plausible theory that could explain the progression of biliary tract injury that predominates in BA is that of an autoimmune-mediated attack on biliary epithelia. After the initial viral insult to the biliary tree, the damaged bile duct epithelial cells may express previously sequestered “self” antigens that are recognized as foreign and elicit autoreactive Th1 cell-mediated inflammation and B cell production of autoantibodies directed at duct epithelia. This mechanism of viral-induced autoimmunity is known as the “bystander activation pathway.” Alternatively, viral proteins may be structurally similar to bile duct epithelia proteins and could elicit cellular and/or humoral autoimmunity based on molecular mimicry. Molecular mimicry entails T or B cell activation in response to microbial antigens with concurrent cross-reactivity to “self” antigens.[57] The strongest evidence for this theory has been gained from murine studies, where autoreactive T cells and autoantibodies targeting bile duct epithelia have been identified. [58–60] In humans, only circumstantial evidence exists for the role of autoimmunity in BA pathogenesis.[2] Rose and Witebsky [61] have put forward the following for categorizing a disease as autoimmune in nature and include: (i) Familial increased incidence of autoimmunity: this question will be answered shortly through data presently being collected within the nationwide Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network (ChiLDREN), a multicentered consortium investigating many aspects of the pathogenesis and treatment of BA. (ii) Lymphocytic infiltrate of the target organ, especially if there is restricted TCR-Vβ usage: this has been clearly established in BA liver tissue (see above, adaptive immunity). (iii) A statistical association with human leukocyte antigen genotype or aberrant expression of HLA class II antigens on the affected organ: normal bile duct epithelium express HLA class I but not class II, which is usually present on professional antigen presenting cells (i.e. B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells) and vascular endothelium. Bile duct epithelium from BA patients aberrantly expresses MHC class II, with strong expression of class II HLA-DR on liver bile duct epithelia.[62, 63] One of the strongest genetic associations with autoimmunity is with the HLA genes. HLA associations with BA have been reported with conflicting results. A European study analyzed the HLA genotypes in 101 BA children and found no significant differences compared to controls.[64] In contrast, a Japanese study of 392 BA patients found significant association between BA and HLA-DR2 as well as a linkage disequilibrium with a high frequency of HLA-A24-B52-DR2.[65] In the United States, through support from ChiLDREN, high resolution genotyping of all HLA class I and class II alleles is nearing completion on 180 BA patients and 360 controls in order to determine if there are any HLA associations with BA.

Humoral Autoimmunity in Biliary Atresia

Humoral immune responses are initiated by the recognition of antigens by B cells specific for a particular antigen. This leads to activation and proliferation of clones of B cells which, in the effector phase, secrete antibodies that may eliminate the antigen. In humans, nearly all of the IgG at birth is maternal in origin. During the first 3–6 weeks of age there is an exponential decrease in IgG with a nadir between 1.5 and 3 months of age. This is the time point when IgG synthesis by the newborn begins, albeit slowly, with adult IgG levels not attained until 5 years of age.[66] Conversely, IgM levels rise rapidly during the first months of life, attaining 75% of adult levels by 1 year of age. An intriguing study on the presence of IgM autoantibodies to defined self molecules in newborn humans was recently reported.[67] Termed “natural autoantibodies”, these neonatal IgMs reacted to a selective set of self antigens, many of which were among the target self antigens associated with autoimmune diseases. The authors concluded that because of the inclusion of some major disease-associated self antigens within the IgM repertoire, pathologic autoimmune disease could arise through a lapse in the regulation of otherwise benign, “natural” autoimmunity. Causes of a “lapse in benign autoimmunity” would include virus infections or environmental toxins.

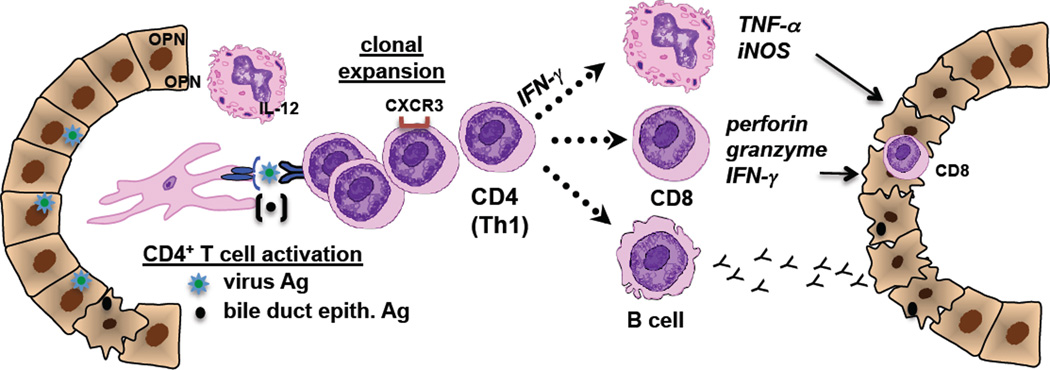

There is sparse information available with regard to humoral autoimmunity in human BA. Over two decades ago Hadchouel et al.[68] described both IgM and IgG immunoglobulin deposits along the basement membrane of bile duct epithelial cells from the extrahepatic remnant of 44 of 128 infants with BA. Periductal IgG deposits were also identified in the majority of liver samples analyzed in older children with BA[60]. Data on the presence of serum autoantibodies are also scant. In preliminary work, Vasiliauskas et al.[69] reported that 10 of 11 patients with BA were positive for serum IgG and IgM antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), with higher levels of the IgM-ANCA in BA patients compared with children and adults with other liver diseases. Lu et al.[60] recently showed that serum samples from ~40% of BA patients had significant elevations in anti-enolase IgM and IgG autoantibodies. Interestingly, anti-enolase antibodies have been found in other autoimmune diseases including autoimmune liver diseases, suggesting that this antibody may be a non-specific marker of autoimmunity.[70–72] Limitations to the human sera analyses included a small number of samples analyzed and the use of rabbit muscle enolase (instead of human enolase) as the source of antigen for ELISA studies (~80% homology between species). Investigations centered on identifying potentially pathogenic, bile-duct specific autoantibodies should be pursued. The potential contribution of adaptive immune and autoimmune responses to bile duct injury in BA is represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Contribution of adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of biliary atresia.

This figure summarizes human investigations pertaining to the role of adaptive immunity in bile duct injury and offers a theory on the role of autoimmune responses in the pathogenesis of disease. Bile duct injury is initiated by virus infection (i.e. CMV) with clonal expansion of virus-specific CD4+ T cells. IL-12, osteopontin (OPN) and CXCR3 chemokine receptors all promote Th1 cell differentiation. These Th1 cells activate effector cells including: 1. macrophages (via CD4+ IFN-γ stimulation) with subsequent generation of TNF-α and iNOS; 2. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells that directly invade epithelia and release cytotoxic molecules; 3. B cells that mature into antibody-producing plasma cells with release of IgM and IgG targeting bile duct epithelia. Over time, proteins from apoptotic bile duct epithelia may be presented and seen as “foreign”, eliciting autoreactive T cell-mediated inflammation that perpetuates the bile duct injury.

Contributors of Dysregulated Immunity in Biliary Atresia

Regulatory T cell (Treg) Deficits

The Treg subset of CD4+ T cells is responsible for controlling the immune response in order to prevent “bystander damage” of healthy cells or tissue. Furthermore, Tregs are necessary to prevent activation of autoreactive T cells. In neonates, the percentage of Tregs increases significantly in the first 5 days of life, reaching adult levels at that time. [73] In BA, deficits in the number or function of Tregs would allow for inflammation to flourish unchecked. In the above mentioned viral immunity study by Brindley et al.[28] the investigators also determined if the presence of virus infection in BA was associated with quantitative changes in Tregs. Peripheral blood Treg quantification revealed significant deficits in Tregs frequencies in BA patients compared to controls, with the most marked deficits in those BA patients who were positive for CMV. The authors concluded that loss of adequate numbers of Tregs in BA would result in decreased inhibition of inflammation or autoreactivity, potentially allowing for exaggerated bile duct injury. Future research should include functional assays of Tregs in both infants and older children with BA as well as quantitative studies in older BA patients in order to determine if Treg deficits persist over time. Novel therapies aimed at expanding Treg populations in BA patients may prove beneficial.

DNA Hypomethylation: a Potential Mechanism Propagating the Inflammatory Response in Biliary Atresia

Changes in DNA methylation can be elicited by drugs, viruses or genetic factors, leading to repression of gene expression.[74] DNA hypomethylation has been implicated as playing a role in autoimmune diseases [75] and in inhibiting lymphocyte differentiation.[76] Importantly, a previous array study identified a set of genes that are known to be regulated by DNA methylation that were significantly increased in BA patients.[76] Based on this knowledge, Matthews et al.[78] hypothesized that DNA hypomethylation may be involved in the pathogenesis of BA. A novel model of BA was utilized in order to test this hypothesis: the zebrafish model of biliary obstruction. The effects of complete inhibition of DNA methylation on the biliary system was assessed using the zebrafish mutant duct-trip (dtp) which contains a mutation in the gene for S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase, resulting in global reduction of DNA methylation. Secondly, wild type larvae were treated with the DNA methylation inhibitor, azaC. Both models showed diminished biliary excretion and poorly defined intrahepatic bile ducts on histology, suggesting a role of DNA hypomethylation in bile duct obstruction. Analysis of hepatic gene expression from the larvae that had received azaC revealed upregulation of genes involved in IFN-γ and NF-κB signaling, antigen processing and presentation and down regulation of Hnf6 pathway, which is known to be important in biliary development. Administration of glucocorticoid to azaC-treated zebrafish resulted in improved biliary flow associated with attenuation of IFN-γ target genes. In addition, the investigators analyzed human BA liver tissue and found a significant decrease in DNA methylation based on bile duct cell nuclear methylcytosine levels compared to controls, providing further significance to the potential role of DNA hypomethylation in BA.

A complimentary study performed by Dong et al.[79] assessed the DNA methylation patterns within IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells from BA patients and found that certain genes were hypomethylated compared to healthy controls. Down-regulation of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT1), DNMT3a and methyl-DNA-binding domain (MBD1) mRNA levels in BA CD4+ T cells was identified. Based on previous reports suggesting an important role of IFN-γ in bile duct injury, the investigators next addressed the question of whether or not the IFN-γ pathway was altered due to DNA hypomethylation. Similar to prior studies, IFN-γ mRNA expression levels in BA patients was significantly increased. Importantly, the IFN-γ gene promoter region was hypomethylated in BA CD4+ T cells, resulting in unchecked regulation of IFN-γ expression. The authors concluded that methylation changes in CD4+ T cells may contribute to bile duct injury in BA by affecting the expression of genes associated with inflammation and autoimmunity.

The Relationship of Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in the Pathogenesis of Biliary Atresia

In this era of genome-wide association studies, a group from China genotyped nearly half a million SNPs in 200 BA patients and 481 controls.[80] The 10 SNPs most highly associated with BA were then analyzed with an independent set of 124 BA patients and 90 controls. The validation study revealed a strong association of BA with the SNP rs17095355 on chromosome 10q24. Two genes in the region of this SNP include X-prolyl aminopeptidase P1(XPNPEP1) and adducin 3 (ADD3). XPNPEP1 is expressed in biliary epithelia and is involved in the metabolism of inflammatory mediators. Genetic defects of XPNPEP1 could result in dysregulation of control of the inflammatory response present in BA. ADD3 is expressed in hepatocytes and biliary epithelia and is involved in the assembly of spectrin-actin membrane protein networks at sites of cell to cell contact. Defective ADD3 could result in excessive deposition of actin and myosin, contributing to biliary fibrosis. The SNP rs17095355 identified in this Chinese study should be investigated in BA patients in the United States and Europe in order to determine if the gene defect spans all ethnicities. In addition, GWAS should be performed in the U.S. and Europe in order to identify novel SNP associations with BA.

Conclusion

Biliary atresia is a devastating disease that leads to liver transplantation in the majority of children. It is essential to decipher the role of both innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of bile duct injury. Understanding the immune-mediated mechanisms of disease will lead to targeted therapies aimed at slowing the progression of disease and delaying (or negating) the need for transplant.

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

National Institutes of Health, NIDDK 1 R01 DK078195 (Mack)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sokol RJ, Mack C. Etiopathogenesis of biliary atresia. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:517–524. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-19032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack CL. The pathogenesis of biliary atresia: evidence for a virus-induced autoimmune disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:233–242. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lykavieris P, et al. Outcome in adulthood of biliary atresia: a study of 63 patients who survived for over 20 years with their native liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:366–371. doi: 10.1002/hep.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreiber RA, Kleinman RE. Genetics, immunology, and biliary atresia: an opening or a diversion? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:111–113. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezerra JA. Potential etiologies of biliary atresia. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:646–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harpavat S, Finegold MJ, Karpen SJ. Patients with biliary atresia have elevated direct/conjugated bilirubin levels shortly after birth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1428–e1433. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landing BH. Considerations of the pathogenesis of neonatal hepatitis, biliary atresia and choledochal cyst - the concept of infantile obstructive cholangiopathy. Prog Pediatr Surg. 1974;6:113–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.al-Masri AN, Werfel T, Jakschies D, von Wussow P. Intracellular staining of Mx proteins in cells from peripheral blood, bone marrow and skin. Mol Pathol. 1997;50:9–14. doi: 10.1136/mp.50.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YH, Chou MH, Du YY, et al. Expression of toll-like receptors and type 1 interferon specific protein MxA in biliary atresia. Lab Invest. 2007;87:66–74. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rauschenfels S, Krassmann M, Al-Masri AN, et al. Incidence of hepatotropic viruses in biliary atresia. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:469–476. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drut R, Drut RM, Gómez MA, et al. Presence of human papillomavirus in extrahepatic biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:530–535. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199811000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahjoub F, Shahsiah R, Ardalan FA, et al. Detection of Epstein Barr virus by chromogenic in situ hybridization in cases of extra-hepatic biliary atresia. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domiati-Saad R, Dawson DB, Margraf LR, et al. Cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus 6, but not human papillomavirus, are present in neonatal giant cell hepatitis and extrahepatic biliary atresia. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2000;3:367–373. doi: 10.1007/s100240010045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischler B, Ehrnst A, Forsgren M, et al. The viral association of neonatal cholestasis in Sweden: a possible link between cytomegalovirus infection and extrahepatic biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:57–64. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199807000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riepenhoff-Talty M, Gouvea V, Evans MJ, et al. Detection of group C rotavirus in infants with extrahepatic biliary atresia. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:8–15. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyler KL, Sokol RJ, Oberhaus SM, et al. Detection of reovirus RNA in hepatobiliary tissues from patients with extrahepatic biliary atresia and choledochal cysts. Hepatology. 1998;27:1475–1482. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steele MI, Marshall CM, Lloyd RE, Randolph VE. Reovirus 3 not detected by reverse transcriptase-mediated polymerase chain reaction analysis of preserved tissue from infants with cholestatic liver disease. Hepatology. 1995;21:697–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilger MA, Matson DO, Conner ME, et al. Extraintestinal rotavirus infections in children with immunodeficiency. J Pediatr. 1992;120:912–917. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81959-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bobo L, Ojeh C, Chiu D, Machado A, et al. Lack of evidence for rotavirus by polymerase chain reaction/enzyme immunoassay of hepatobiliary samples from children with biliary atresia. Pediatr Res. 1997;41:229–234. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199702000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin YC, Chang MH, Liao SF, et al. Decreasing rate of biliary atresia in Taiwan: a survey, 2004–2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e530–e536. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko HM, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: three autopsy case reports. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:337–342. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martelius T, Krogerus L, Höckerstedt K, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with increased inflammation and severe bile duct damage in rat liver allografts. Hepatology. 1998;27:996–1002. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans PC, Coleman N, Wreghitt TG, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection of bile duct epithelial cells, hepatic artery and portal venous endothelium in relation to chronic rejection of liver grafts. J Hepatol. 1999;31:913–920. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischler B, Woxenius S, Nemeth A, Papadogiannakis N. Immunoglobulin deposits in liver tissue from infants with biliary atresia and the correlation to cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischler B, Svensson JF, Nemeth A. Early cytomegalovirus infection and the long-term outcome of biliary atresia. Acta Paediatrica. 2009;98:1600–1602. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen C, Zheng S, Wang W, Xiao XM. Relationship between prognosis of biliary atresia and infection of cytomegalovirus. World J Pediatr. 2008;4:123–126. doi: 10.1007/s12519-008-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Y, Yu J, Zhang R, et al. The perinatal infection of cytomegalovirus is an important etiology for biliary atresia in China. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51:109–113. doi: 10.1177/0009922811406264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brindley SM, Lanham AM, Karrer FM, et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific T-cell reactivity in biliary atresia at the time of diagnosis is associated with deficits in regulatory T cells. Hepatology. 2012;55:1130–1138. doi: 10.1002/hep.24807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane T, Lachmann HJ. The emerging role of interleukin-1beta in autoinflammatory diseases. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:361–368. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Cholangiopathy with respect to biliary innate immunity. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:793569. doi: 10.1155/2012/793569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuang JH, Chou MH, Wu CL, Du YY. Implication of innate immunity in the pathogenesis of biliary atresia. Chang Gung Med J. 2006;29:240–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovgren T, Tarantolo SR, Evans C, et al. Induction of interferon-alpha production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells by immune complexes containing nucleic acid released by necrotic or late apoptotic cells and lupus IgG. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1861–1872. doi: 10.1002/art.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saito T, Hishiki T, Terui K, et al. Toll-like receptor mRNA expression in liver tissue from patients with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:620–626. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182307c9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harada K, Sato Y, Itatsu K, Isse K, et al. Innate immune response to double-stranded RNA in biliary epithelial cells is associated with the pathogenesis of biliary atresia. Hepatology. 2007;46:1146–1154. doi: 10.1002/hep.21797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tracy TF, Jr, Dillon P, Fox ES, Minnick K, Vogler C. The inflammatory response in pediatric biliary disease: macrophage phenotype and distribution. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urushihara N, Iwagaki H, Yagi T, et al. Elevation of serum interleukin-18 levels and activation of Kupffer cells in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:446–449. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(00)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi H, Puri P, O'Briain DS, et al. Hepatic overexpression of MHC class II antigens and macrophage-associated antigens (CD68) in patients with biliary atresia of poor prognosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:590–593. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90714-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davenport M, Gonde C, Redkar R, et al. Immunohistochemistry of the liver and biliary tree in extrahepatic biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1017–1025. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.24730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mack CL, Tucker RM, Sokol RJ, et al. Biliary atresia is associated with CD4+ Th1 cell-mediated portal tract inflammation. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:79–87. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000130480.51066.FB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shih HH, Lin TM, Chuang JH, et al. Promoter polymorphism of the CD14 endotoxin receptor gene is associated with biliary atresia and idiopathic neonatal cholestasis. Pediatrics. 2005;116:437–441. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arikan C, Berdeli A, Ozgenc F, et al. Positive association of macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene-173G/C polymorphism with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:77–82. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000192247.55583.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donn R, Alourfi Z, Zeggini E, et al. A functional promoter haplotype of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is linked and associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1604–1610. doi: 10.1002/art.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nohara H, Okayama N, Inoue N, et al. Association of the-173 G/C polymorphism of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene with ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:242–246. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glaser SS. Biliary atresia: is lack of innate immune response tolerance key to pathogenesis? Liver Int. 2008;28:587–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bezerra JA, Tiao G, Ryckman FC, et al. Genetic induction of proinflammatory immunity in children with biliary atresia. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1653–1659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmed AF, Ohtani H, Nio M, et al. CD8+ T cells infiltrating into bile ducts in biliary atresia do not appear to function as cytotoxic T cells: a clinicopathological analysis. J Pathol. 2001;193:383–389. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::aid-path793>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shinkai M, Shinkai T, Puri P, Stringer MD. Increased CXCR3 expression associated with CD3-positive lymphocytes in the liver and biliary remnant in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:950–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohya T, Fujimoto T, Shimomura H, Miyano T. Degeneration of intrahepatic bile duct with lymphocyte infiltration into biliary epithelial cells in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:515–518. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mack CL, Falta MT, Sullivan AK, et al. Oligoclonal expansions of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in the target organ of patients with biliary atresia. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:278–287. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Narayanaswamy B, Gonde C, Tredger JM, et al. Serial circulating markers of inflammation in biliary atresia--evolution of the post-operative inflammatory process. Hepatology. 2007;46:180–187. doi: 10.1002/hep.21701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dillon P, Belchis D, Tracy T, Cilley R, et al. Increased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in biliary atresia. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:263–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghoneim EM, Sira MM, Abd Elaziz AM, et al. Diagnostic value of hepatic intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in Egyptian infants with biliary atresia and other forms of neonatal cholestasis. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:763–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arikan C, Berdeli A, Kilic M, et al. Polymorphisms of the ICAM-1 gene are associated with biliary atresia. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2000–2004. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9914-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vejchapipat P, Poomsawat S, Chongsrisawat V, et al. Elevated serum IL-18 and interferon-gamma in medium-term survivors of biliary atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2012;22:29–33. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitington PF, Malladi P, Melin-Aldana H, et al. Expression of osteopontin correlates with portal biliary proliferation and fibrosis in biliary atresia. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:837–844. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000161414.99181.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Honsawek S, Vejchapipat P, Chongsrisawat V, et al. Association of circulating osteopontin levels with clinical outcomes in postoperative biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:283–288. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oldstone MB. Molecular mimicry, microbial infection, and autoimmune disease: evolution of the concept. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;296:1–17. doi: 10.1007/3-540-30791-5_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mack CL, Tucker RM, Lu BR, et al. Cellular and humoral autoimmunity directed at bile duct epithelia in murine biliary atresia. Hepatology. 2006;44:1231–1239. doi: 10.1002/hep.21366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shivakumar P, Sabla G, Mohanty S, et al. Effector role of neonatal hepatic CD8+ lymphocytes in epithelial injury and autoimmunity in experimental biliary atresia. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:268–277. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu BR, Brindley SM, Tucker RM, et al. Alpha-enolase autoantibodies cross-reactive to viral proteins in a mouse model of biliary atresia. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1753–1761. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rose NR, Bona C. Defining criteria for autoimmune diseases (Witebsky's postulates revisited) Immunol Today. 1993;14:426–430. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90244-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Broome U, Nemeth A, Hultcrantz R, Scheynius A. Different expression of HLA-DR and ICAM-1 in livers from patients with biliary atresia and Byler's disease. J Hepatol. 1997;26:857–862. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80253-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feng J, Li M, Gu W, Tang H, Yu S. The aberrant expression of HLA-DR in intrahepatic bile ducts in patients with biliary atresia: an immunohistochemistry and immune electron microscopy study. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1658–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donaldson PT, Clare M, Constantini PK, et al. HLA and cytokine gene polymorphisms in biliary atresia. Liver. 2002;22:213–219. doi: 10.1046/j.0106-9543.2002.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yuasa T, Tsuji H, Kimura S, et al. Human leukocyte antigens in Japanese patients with biliary atresia: retrospective analysis of patients who underwent living donor liver transplantation. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Holladay SD, Smialowicz RJ. Development of the murine and human immune system: differential effects of immunotoxicants depend on time of exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):463–473. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Merbl Y, Zucker-Toledano M, Quintana FJ, Cohen IR. Newborn humans manifest autoantibodies to defined self molecules detected by antigen microarray informatics. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:712–718. doi: 10.1172/JCI29943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hadchouel M, Hugon RN, Odievre M. Immunoglobulin deposits in the biliary remnants of extrahepatic biliary atresia: a study by immunoperoxidase staining in 128 infants. Histopathology. 1981;5:217–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1981.tb01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vasiliauskas E, Cobb L, Vidrich LA, et al. Biliary atresia- an autoimmune disorder? Hepatology. 1995;22(87) [Google Scholar]

- 70.Akisawa N, Maeda T, Iwasaki S, Onishi S. Identification of an autoantibody against alpha-enolase in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:845–851. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orth T, Kellner R, Diekmann O, et al. Identification and characterization of autoantibodies against catalase and alpha-enolase in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roozendaal C, de Jong MA, van den Berg AP, van, et al. Clinical significance of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in autoimmune liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2000;32:734–741. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grindebacke H, Stenstad H, Quiding-Järbrink M, et al. Dynamic development of homing receptor expression and memory cell differentiation of infant CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:4360–4370. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kruger DH, Schroeder C, Santibanez-Koref M, Reuter M. Avoidance of DNA methylation. A virus-encoded methylase inhibitor and evidence for counterselection of methylase recognition sites in viral genomes. Cell Biophys. 1989;15:87–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02991582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogasawara H, Okada M, Kaneko H, et al. Possible role of DNA hypomethylation in the induction of SLE: relationship to the transcription of human endogenous retroviruses. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee PP, Fitzpatrick DR, Beard C, et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 2001;15:763–774. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang DY, Sabla G, Shivakumar P, et al. Coordinate expression of regulatory genes differentiates embryonic and perinatal forms of biliary atresia. Hepatology. 2004;39:954–962. doi: 10.1002/hep.20135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Matthews RP, Eauclaire SF, Mugnier M, et al. DNA hypomethylation causes bile duct defects in zebrafish and is a distinguishing feature of infantile biliary atresia. Hepatology. 2011;53:905–914. doi: 10.1002/hep.24106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dong R, Zhao R, Zheng S. Changes in epigenetic regulation of CD4+ T lymphocytes in biliary atresia. Pediatr Res. 2011;70:555–559. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318232a949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garcia-Barcelo MM, Yeung MY, Miao XP, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a susceptibility locus for biliary atresia on 10q24.2. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2917–2925. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]