Primary neoplasia involving a joint is uncommon in the dog, but synovial sarcomas do occur, most frequently in the stifle joint (1,2,3). The clinical significance of these tumors is that they can masquerade as cranial cruciate ligament disease (CCLD), as illustrated by the following cases.

Case #1

A 6-year-old male golden retriever was presented with a 1-month history of progressive lameness in the left hind limb. Apparently, the dog had been diagnosed with rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) in the right hind limb at 5 mo of age and had undergone 2 surgical procedures to correct it. Examination of the left hind limb showed pain on stifle manipulation, joint effusion, but no joint instability. Radiographs of the left stifle showed no bony changes; however, obliteration of the infrapatellar fat pad shadow due to joint effusion was evident on the lateral projection (Figure 1). Exploratory arthrotomy revealed proliferative tissue in and around the stifle joint associated with the synovium. Histopathologic examination of this tissue led to a diagnosis of anaplastic neoplasia consistent with synovial sarcoma. The owners opted to euthanize the dog.

Figure 1. Lateral projection of the stifle from case #1. Note the obliteration of the shadow of the infrapatellar fat pad due to joint effusion and proliferative synovial tissue.

Case #2

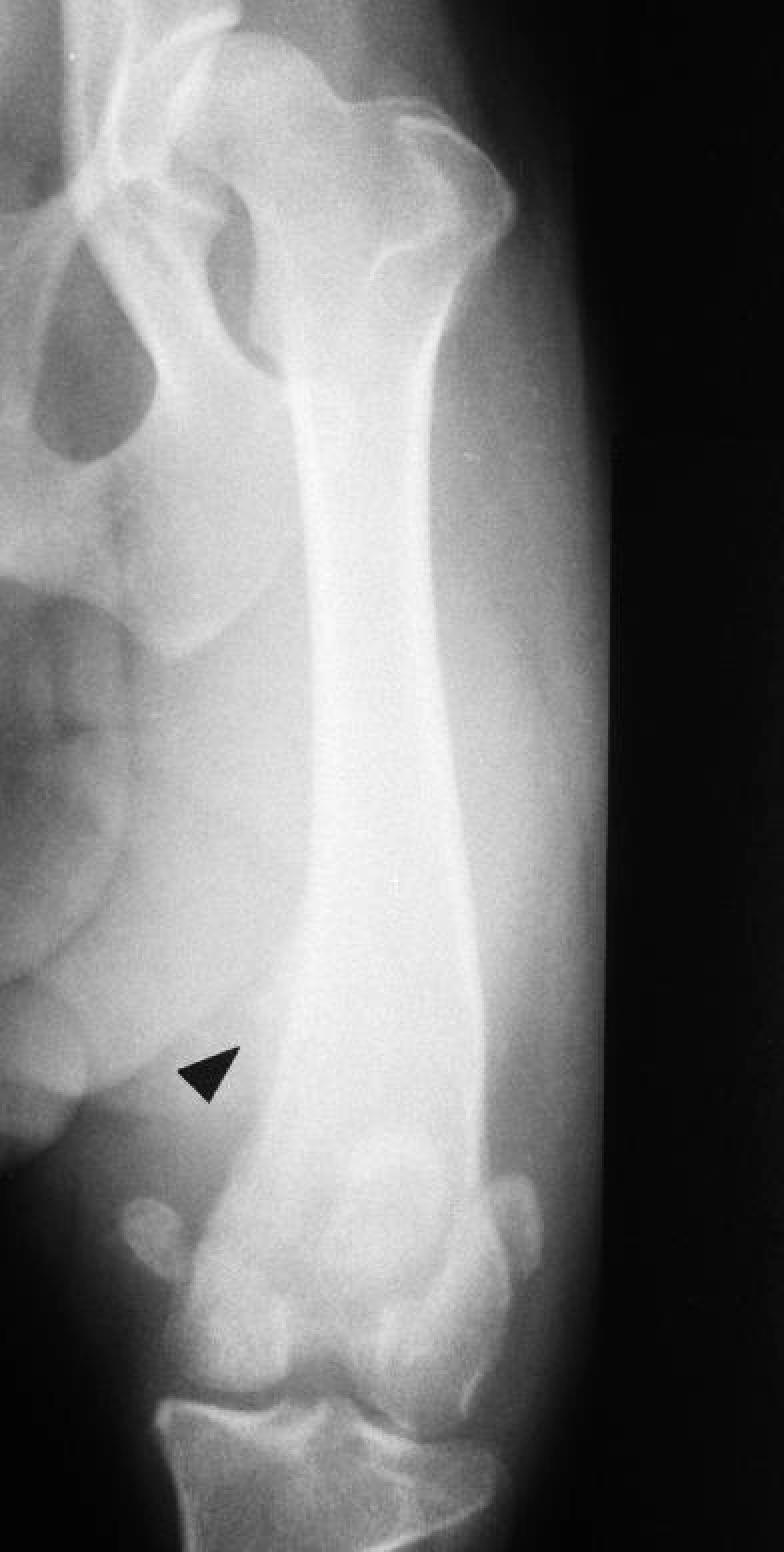

An 18-month-old, female English springer spaniel was referred by a colleague for evaluation of a suspected CCL injury. The dog had been lame in the left hind limb for about 1 mo. The lameness had become worse recently, such that the dog was completely nonweight bearing. Examination revealed significant pain on stifle manipulation, a thickened joint, and moderate atrophy of the quadriceps muscle. Under general anesthesia, a cranial drawer sign could not be elicited, but a soft tissue mass, 2 to 3 cm in diameter, could be palpated caudal to the stifle joint. Radiographs showed bone lysis and a periosteal reaction associated with the caudal aspect of the medial femoral condyle (Figures 2, 3). The soft tissue mass and medial femoral condyle were biopsied, and a swab for culture and sensitivity testing was taken. The only significant findings came from histopathologic examination of the soft tissue mass, which was categorized as an undifferentiated sarcoma of mesenchymal origin. The dog was euthanized.

Figure 2. Craniocaudal projection of the stifle from case #2. The arrow points to the periosteal reaction associated with the neoplasm in the caudal aspect of the stifle joint.

Figure 3. Lateral projection of the stifle from case #2. Note the lytic lesion involving the medial femoral condyle.

Primary joint tumors are seen most often in large breed dogs with a mean age of about 8 y and a range of 12 mo to 12 y (1,2). Most such tumors are malignant and are thought to arise from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells in the area of large joints; most often the stifle and elbow (1,2,3,4). In many cases, these mesenchymal cells differentiate into synovioblasts, resulting in a synovial cell sarcoma; however, many other histologic tumor types are possible (1).

Joint tumors involving the stifle can give the clinical appearance of CCLD: to wit, a large breed dog with a chronic hind limb lameness and a thickened stifle. The history and a physical examination may highlight some important differences however. Joint tumors are characterized by a chronic, slowly progressive lameness, while dogs with CCL injury are initially very lame and improve to some degree with time. Perhaps the most important “red flag” to differentiate the 2 conditions is pain. While dogs with CCL injury may be somewhat in pain, particularly in the first few days after their injury or if the joint is firmly manipulated, dogs with joint tumors are markedly in pain and often progress to complete nonweight bearing in the affected limb. In the absence of a distinct soft tissue mass, other findings on physical examination may be equivocal. Periarticular thickening and joint effusion are common in patients with CCL injury, and although no joint instability will be detected in cases with neoplasia, this may also be the case with partial tears of the CCL. Radiographically, changes may be minimal but can progress to soft tissue swelling, periosteal reaction, and bony lysis if the tumor cells invade cancellous bone from the articular margins (1). Bony lysis, on both sides of a joint in an older, large breed dog is strongly suggestive of synovial cell sarcoma (1,3,4).

The presence of chronic hind limb lameness with gross or radiographic stifle changes, or both, warrants an exploratory arthrotomy. In the face of abnormal bone or soft tissue and a normal CCL, biopsy will usually supply a diagnosis. Differential diagnoses include septic and immune-mediated arthridities.

Management of malignant joint tumors begins with the very significant challenge of analgesia. Adequate analgesia may be difficult to maintain with anything less than narcotic analgesics. Indeed, amputation is the recommended therapy, not only in trying to arrest tumor spread, but also to relieve pain. Chemotherapy and radiation protocols have been described as an adjunct to amputation (3,4,5).

The prognosis for most malignant joint tumors, while marginally better than primary appendicular bone neoplasias, such as osteosarcoma, is guarded to poor. Metastasis to lung or lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis is estimated at only 25% to 30%, but local spread and recurrance is common, and the survival rate past 1 y has been reported at only 25% (3,4).

Figure.

References

- 1.Whitelock RG, Dyce J, Houlton JEF, Jefferies AR. A review of 30 tumors affecting joints. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 1997;10:146–152.

- 2.Bellah JR, Patton CS. Nonweightbearing lameness secondary to synovial sarcoma in a young dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986; 188:730–732. [PubMed]

- 3.Denny HR, Butterworth SJ. A Guide to Canine and Feline Orthopedic Surgery, 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Sci 2000:77–80.

- 4.Dyce J. Neoplastic and neoplasia-like conditions of joints. In: Houlton JEF, Collinson RW, eds. Manual of Small Animal Arthrology. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire: British Small Anim Vet Assoc 1994:136.

- 5.Page RL. Musculoskeletal neoplasia: biology and clinical management. In: Olmstead ML, ed. Small Animal Orthopedics. St. Louis: Mosby 1995:417–426.