Abstract

Objectives:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the major public health problems worldwide which is transmitted through contact with infected blood or blood products. One of the most prevalent modes of HCV transmission is injecting drug with unclean needles or syringes. Therefore intravenous drug users (IVDUs) are the most important group who should be considered. The aim of this study was to evaluate seroprevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus in IVDUs population.

Methods:

The cross-sectional study was carried out on intravenous drug users who attended health and social care Drop-in centers during November 2008 to February 2009 in Isfahan province, Iran. Data was gathered using interviewer-administered questionnaire including demographic characteristics and main risk factors for HCV infection. 5ml venous blood sample was obtained from each subject. The HCV-Ab test was performed on all blood samples by ELISA. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistical methods and multiple logistic regressions by SPSS software, version 15.

Results:

The mean age of participants was 31.77 ± 8.51. 503 (94.7%) were men and 28 (5.3%) were women. HCV seroprevalence was 47.1% (95% CI: 42.9, 51.3). The multiple logistic regressions demonstrated that history of tattooing (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.02-2.90), history of imprisonment (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.40-4.42) and sharing needles/syringes (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.54-4.95) are significant predictors of risk of HCV in IVDU population.

Conclusions:

In conclusion, according to the high prevalence of HCV infection among IVDUs and high adds of HCV infection from tattooing, sharing of needles/syringes and imprisonment, effective harm reduction programs should be expanded among IVDUs to prevent new HCV infections.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, High-risky behaviors, Intravenous drug users, Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the major public health problems worldwide which is transmitted through contact with infected blood or blood products. HCV infection causes critical medical consequence such as cirrhosis and liver diseases.[1] Among individuals with HCV infection, 85% will acquire chronic HCV infection.[2] WHO has reported a prevalence of 3% for HCV in the world and more than 170 million persons have been infected with this virus globally.[3] Countries in Africa, Asia and Southern Europe have demonstrated high prevalence of HCV infection.[4] There is no overall estimate of hepatitis C infection in Iran. A systematic review study on HCV which assessed general population in Iran, has estimated prevalence of 0.16% for HCV infection. The prevalence ranged from 0% in Khuzestan and Tahren province to 1.3% in Guilan province.[5] HCV infection can be transmitted through many routes. Due to the most prevalent mode of HCV transmission is injecting drug with unclean needles or syringes, intravenous drug users (IVDUs) are the most important group who should be considered.[1] It has been estimated 2-4 million people in developing countries possess HCV infection driven by unsafe injection drug use each year that is extending to other population.[4] There is wide range of prevalence estimates around the world. Considering a systematic review study's results, prevalence of HCV infection among IVDUs ranged from 1.9% to 100%.[6] Identification of HCV infection epidemiology is important to perform proper harm reduction program to control and prevent infection transmission and chronic liver diseases.[4] Therefore the seroprevalence and main way of HCV transmission in developing countries should be accessible.[7] There aren’t enough appropriate epidemiological studies of HCV in developing countries. A number of studies have evaluated HCV prevalence in IVDUs population in Iran. More recent studies among IVDUs have indicated HCV prevalence of 11.2-88.9%.[2,8–18]

Those observations raised concern about IVDUs and high risky behaviors among them and as a result transmission and spread of HCV.[19] Therefore it is considerable to prevent HCV and decrease its dire consequences like liver diseases by decrease of infection among IVDUs and assessing other high-risky behaviors among them to control extension of infection from them to other groups and public population eventually.[4]

According to lack of information on HCV prevalence among IVDUs in Isfahan province, Iran, this study evaluated the prevalence and risk factors for HCV infection among IVDUs referred drop in centers (DICs) in that province. DICs are one of the important centers where present services to social vulnerable individuals. They conduct harm reduction programs with aim to prevent transmission of infection diseases and reduce spread of them in public community. The harm reduction programs include exchanging needles or syringes, distribution of condoms and providing methadone maintenance treatment among IVDUs who refer there. Therefore DICs are one of the places of IVDUs aggregation. The main aim of this study is to provide worth information about prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C in IVDUs population and it will be helpful for prevention and therapeutic interventions.

METHODS

The cross-sectional study was carried out on intravenous drug users who attended health and social care Drop-in centers during November 2008 to February 2009 in Isfahan province, Iran. Required information was gathered using interviewer-administered questionnaire including demographic characteristics and main risk factors for HCV infection. For each participant an educated interviewer, who was social worker and had been working with our target population and was trusty for them, filled out questionnaires with face-to-face interview. All IVDUs who referred to DICs were requested to take part in the study after being informed about the goal and process of the study and promised all data were kept private. According to ethical issues the individual took part in the study voluntary and they were not encouraged for participation. After that they filled out a consent form. Also the subjects were allowed to leave out any question which they weren’t satisfied about answering to it. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Face and content validity of questionnaire was confirmed by eight experts. Cronbach Alpha indicated reasonable reliability (r = 0.78).

After completion of questionnaire, 5 ml venous blood sample was obtained from each subject. Serum samples were transferred to the Isfahan infectious diseases research center laboratory and stored at –20 °C. The HCV-Ab test was performed on all blood samples by Italian Diasorin enzymelinked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) kits.

The collected data was analyzed by SPSS software, version 15. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus was estimated using descriptive statistical methods. Bivariate associations between risk factors and HCV were assessed by Chi-square test.

Multiple logistic regressions were applied to calculate adjusted odds Ratio for risk factors related to HCV. A probability of <0.05 was considered as statistical significant. All variables that were found to be significant in the bivariate analysis were taken into logistic regression. According to the multicollinearity is a statistical phenomenon in which two or more predictor variables in a multiple regression model are highly correlated and it affects parameter estimations. We include one of variables in those groups that had association with each other into regression model after consultation with clinicians. For example among history of imprisonment, duration of being in prison and number of imprisonment, we only involved history of imprisonment into regression model to avoid collinearity.

RESULTS

Of 539 intravenous drug users who participated in this study, the sample blood of 531 individuals could be tested for HCV positivity. Therefore 531 subjects were analyzed according to the obtained information. We found HCV seroprevalence was 47.1% (95% CI: 42.9, 51.3) among IVDUs.

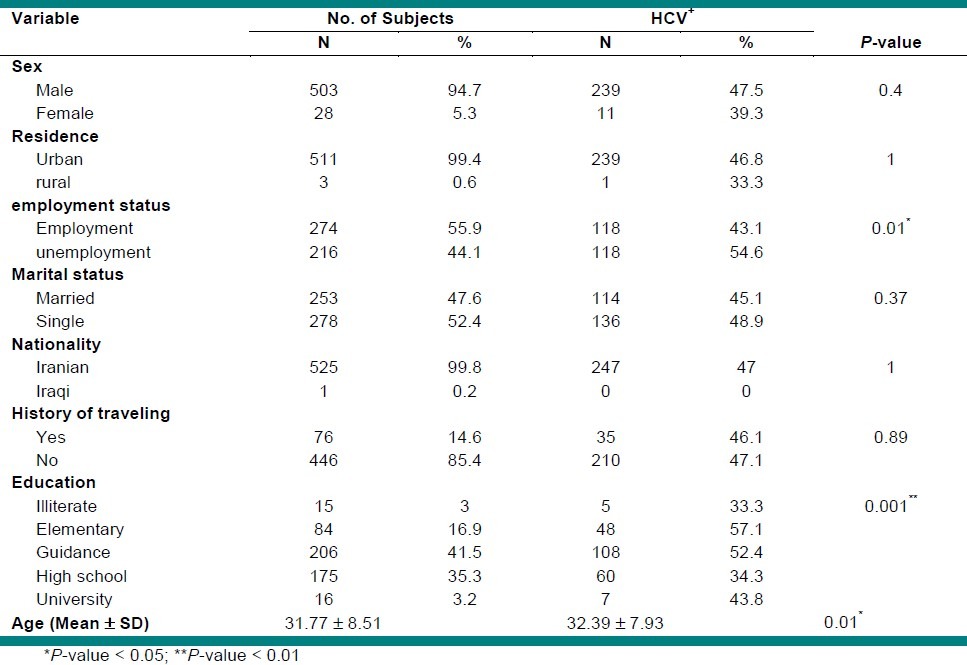

The mean age of participants was 31.77 ± 8.51. 503 (94.7%) were men and 28 (5.3%) were women. 274 (55.9%) of subjects were employed and 278 (52.4%) were single. Regarding education, most of the participants (66.3%) had low level of education (under Diploma). Table 1 describes the distribution of HCV prevalence within each demographic characteristics and their bivariate association. As seen in this table age, employment status and education had significant association with HCV seropositivity.

Table 1.

Bivariate association between demographic characteristics and HCV seropositivity

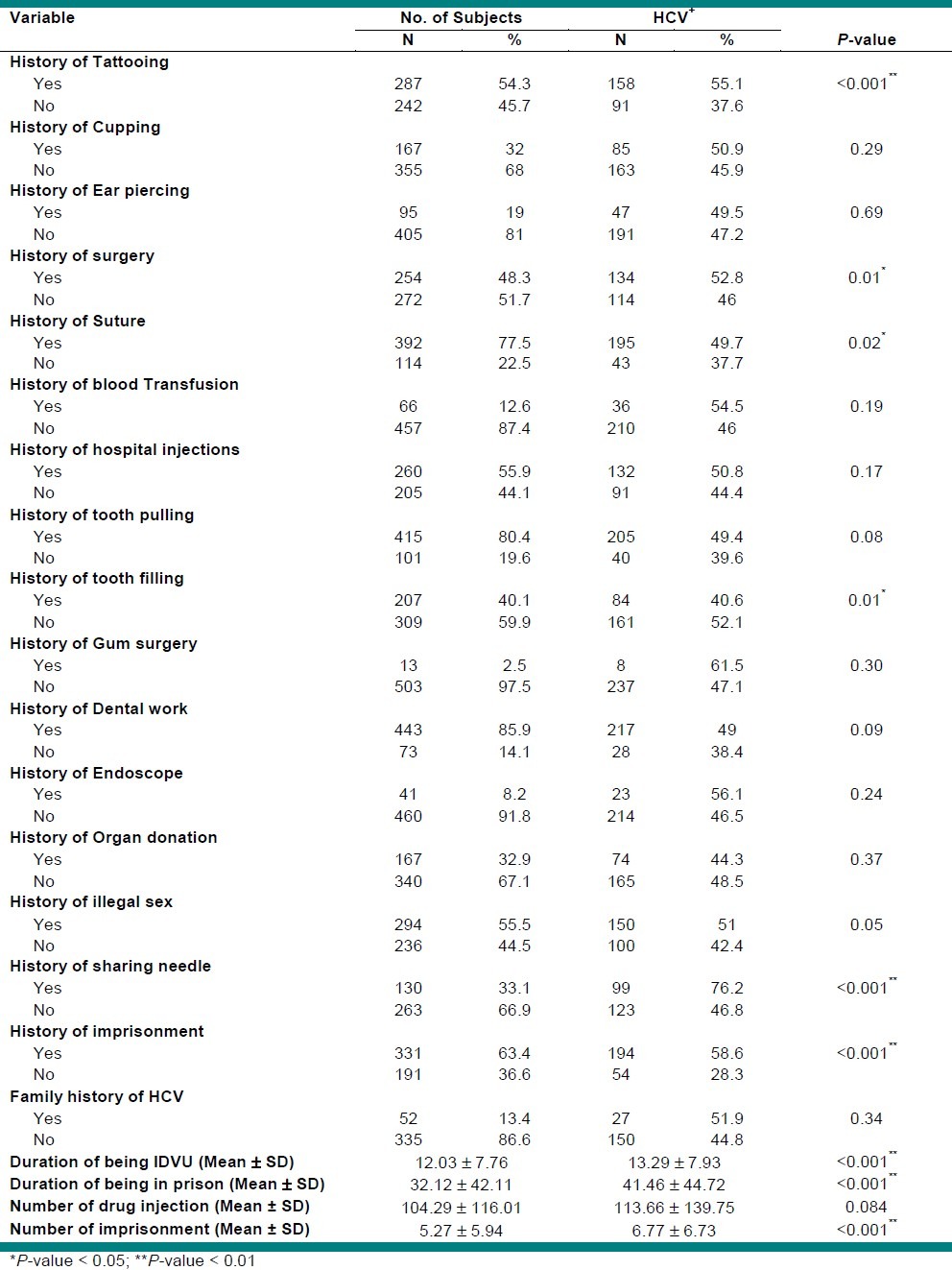

Some potential risk factors for HCV were shown in table 2. Sharing needles/syringes and history of illegal sex had been reported by 130 (33.1%) and 294 (55.5%) subjects respectively. Among male participants who had history of illegal sexual activity, 228 (79.7%) had heterosexual contact, 95 (33.2%) had experience of homosexual contact, 136 (48.4%) had reported using condom in their contact and 127 (44.3%) had practiced sexual contact with female sex workers. Of sexual active participants, 47 (18.7%) had one sexual partner, 97 (38.6%) two to nine sexual partners, 106 (42.2%) more than nine sexual partners and 70 (30%) reported sexual practice with IVDUs. There were no significant association between sexual behaviors and HCV prevalence.

Table 2.

Bivariate association between potential risk factors and HCV seropositivity

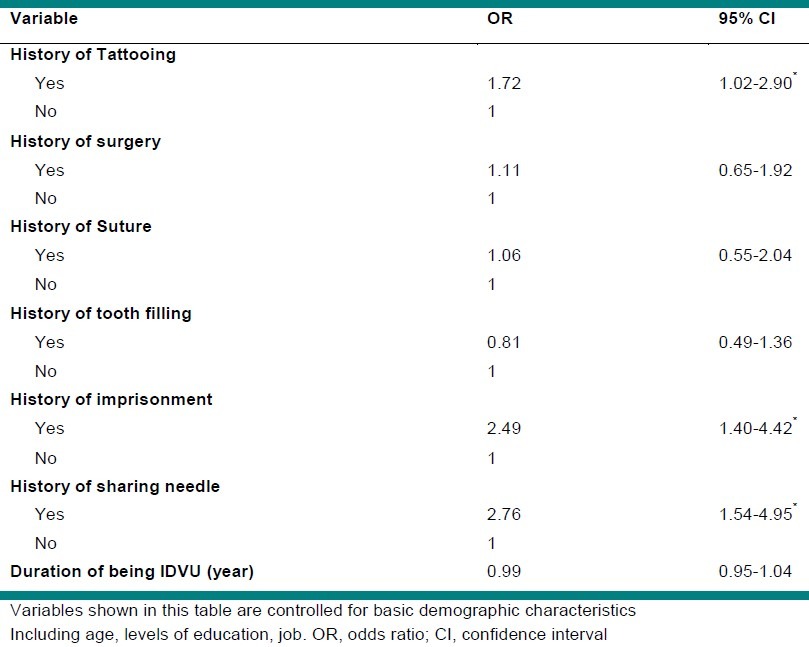

As depicted in table 2, variety of risk factors were associated with HCV prevalence such as history of tattooing, surgery, suture, tooth filling, sharing needles/syringes, history of imprisonment, duration of being IDVU, duration of being in prison and number of imprisonment. The multiple logistic regressions demonstrated that history of tattooing, history of imprisonment and sharing needles/syringes are significant predictors of risk of HCV in IVDU population. The other variables which had been significant in bivariate analysis were not statistically significant in multiple logistic regression [Table 3].

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression of potential risk factors for HCV seropositivity

DISCUSSION

In this study we assessed the seroprevalence of HCV infection among intravenous drug users. Prevalence of HCV positivity was 47.1%. Different studies have estimated the seroprevalence of HCV among IVDUs. Similar studies around the world have shown wide range. In a systematic review study which was done by Aceijas et al.,[6] prevalence of HCV was evaluated among injecting drug users between 1998 and 2005. They have reported various estimates, 10-96% in Eastern Europe and central Asia, 10-100% in South and South-East Asia, 34-93% in East-Asia and the Pacific, 5-60% in North Africa and the Middle East, 2-100% in Latin America, 8-90% in North America, 25-88% in Australia and New Zealand and 2-93% in Western Europe. But in Colombia and Lebanon, HCV prevalence was less than 20%. In Studies which were conducted in the population of IVDUs in Iran, high HCV prevalence was observed (11.2% to 88.9%)[2,8–18]. Except for study in Shahr-e-Kord (11.2%), all of studies have reported HCV prevalence of at least 30%. According to the high seropositivity of HCV among IVDUs, they play significant epidemiological role in the transmission of HCV infection. Therefore this population is the most important group who should be considered to control and decrease the spread of HCV among them.[20]

Since the high-risky behaviors in intravenous drug users frequently happen, we evaluated some risk factors associated with HCV positivity. The result of multiple logistic regression showed subjects who had history of tattooing, sharing needles/syringes and imprisonment, were more likely to be positive for HCV.

Our findings displayed compare with non-needle-sharing, participants who shared needles /syringes had significant higher odds of having HCV infection. Odds of getting HCV infection among this group was 2.76 times more than non-needle–sharing participants. This finding is in agreement with some earlier studies.[3,10,13,17–19,21,22] Thus, conducting proper harm reduction programs such as exchange needles/ syringes among IVDUs are urgently needed.

Tattooing is one of the fashionable human activities these days. In our study there was significant association between history of tooting and HCV positivity. Having experience of tattooing increases odds of infection by 72%. In the United States, Samuel et al.[23] have observed doing tattoo inside prison was related with HCV prevalence (OR = 3.4). In Australia and Italy it was also significant independent risk factor for HCV positivity among a group of prisoners (OR = 2.7 and 1.91 respectively).[24,25] A number of studies among IVDUs in Iran have also found significant association between being tattooed and HCV prevalence.[8,11,18] Also Pourahmad et al.[3] have reported tattooing as significant risk factors of HCV positivity in sample of prisoners. Two other studies[12,26] found this relationship among addicted prisoners. Since the tattooing is common in Iran prisons and most of the people who attend this behavior, do it in illegal places, it is probably being done using unsteril equipments. As a result, contact with infections blood can be occurred through unsafe tattooing.[3]

Consistent with previous investigations,[2,10,14,18,22] we found that imprisonment is another significant independent factor for HCV seropositivity. Odds of being HCV positive among IVDUs with history of incarceration was 2.49 times more than odds of carrying the infection among IVDUs without history of being in prison. Prisons are substantial places where the prisoners experience high-risky behaviors there such as sharing of injection equipments, tattooing and unprotected sexual behaviors. There-fore imprisonment may accompany with risky behaviors that increase risk of infection transmission in prison and prisons should be considered as a priority site to make decision concerning harm reduction strategies among prisoners.[14]

Similar to another study in Iran,[14] we found no statistical association between sexual activity and prevalence of HCV. This finding is not consistent with previous reports.[21,22] It may be because of religious beliefs that affect answering to sexual activities questions.

Ultimately, this study has some limitations. First, the sample is not representative of intravenous drug users as subjects took part in the study from only health and social care centers (DICs) in Isfahan province. Furthermore, our data was gained based on self-reported information through interview and participants were allowed to skip any questions which they weren’t satisfied about answering to them. Therefore, there were some unanswered questions especially about sexual behaviors.

In conclusion, according to the high prevalence of HCV infection among IVDUs and high adds of HCV infection from tattooing, sharing of needles/syringes and imprisonment, effective harm reduction programs should be expanded among IVDUs to prevent new HCV infections. In addition it is important that potential affection of prison on spread of HCV infection throughout the community be taken into consideration in order to control transmission of HCV infection society.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This paper is extracted from the research project No.287167 research chancellor, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Holtzman D, Barry V, Ouellet LJ, Jarlais DC, Vlahov D, Golub ET, et al. The influence of needle exchange programs on injection risk behaviors and infection with hepatitis C virus among young injection drug users in select cities in the United States, 1994–2004. Prev Med. 2009;49:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alizadeh AH, Alavian SM, Jafari K, Yazdi N. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and its related risk factors in drug abuser prisoners in HamedanIran. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4085–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pourahmad M, Javady A, Karimi I, Ataei B, Kassaeian N. Seroprevalence of and risk factors associated with hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus among prisoners in Iran. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2007;15:368–372. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jatapai A, Nelson KE, Chuenchitra T, Kana K, Eiumtrakul S, Sunantarod E, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among young Thai men. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:433–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alavian SM, Ahmadzad-Asl M, Lankarani KB, Shahbabaie MA, Bahrami Ahmadi A, Kabir A. Hepatitis C infection in the general population of Iran: a systematic review. Hepat Mon. 2009;9:211–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aceijas C, Rhodes T. Global estimates of prevalence of HCV infection among injecting drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:352–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–67. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zali MR, Aghazadeh R, Nowroozi A, Amir-Rasouly H. Anti-HCV antibody among Iranian IV drug users: is it a serious problem. Arch Iran Med. 2001;4:115–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahbar AR, Rooholamini S, Khoshnood K. Prevalence of HIV infection and other blood-borne infections in incarcerated and non-incarcerated injection drug users (IDUs) in Mashhad, Iran. Int J Drug Policy. 2004;15:151–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirnaseri S, Poustchi H, Naseri Moghadam S, Nouraei S, Tahaghoghi S, Afshar P, et al. HCV in intravenous drug users. Govaresh J. 2005;10(2):80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamani S, Ichikawa S, Nassirimanesh B, Vazirian M, Ichikawa K, Gouya MM, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among injecting drug users in Tehran. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:359–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amiri ZM, Rezvani M, Shakib RJ, Shakib AJ. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and risk factors of drug using prisoners in Guilan province. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imani R, Karimi A, Rouzbahani R, Rouzbahani A. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infection among intravenous drug users in Shahr-e-Kord, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:1136–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alavi SM, Alavi L. Seroprevalence study of HCV among hospitalized intravenous drug users in Ahvaz, Iran (2001-2006) J Infect Public Health. 2009;2:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirahmadizadeh A, Majdzadeh R, Mohammad K, Forouzanfar M. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections and related behavioral determinants among injecting drug users of drop-in centers in Iran. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2009;11:325–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahimi-Movaghar A, Razaghi EM, Sahimi-Izadian E, Amin-Esmaeili M. HIV, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus co-infections among injecting drug users in Tehran, Iran. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alavi SM, Behdad F. Seroprevalence study of hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus among hospitalized intravenous drug users in Ahvaz, Iran (2002-2006) Hepat Mon. 2010;10:101–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ataei B, Babak A, Yaran M, Kassaian N, Nokhodian Z, Meshkati M, et al. Hepatitis C in Intravenous Drug Users: Seroprevalence and Risk Factors. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2011;28:1537–1545. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todd CS, Abed AMS, Strathdee SA, Scott PT, Bo-tros BA, Safi N, et al. HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B infections and associated risk behavior in injection drug users, Kabul, Afghanistan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1327–31. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.070036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu N, Ge Q, Feng Q, Zhang J, Liu X, Sun C, et al. High Prevalence of Hepatitis C virus Among Injection Drug Users in Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, China. Indian J Virol. 2011;22:77–83. doi: 10.1007/s13337-011-0041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Lum PJ, Bourgois P, Stein E, Evans JL, et al. Hepatitis C virus seroconversion among young injection drug users: relationships and risks. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1558–64. doi: 10.1086/345554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stark K, Bienzle U, Vonk R, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I. History of syringe sharing in prison and risk of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus infection among injecting drug users in Berlin. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:1359–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.6.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuel M, Doherty P, Bulterys M, Jenison S. Association between heroin use, needle sharing and tattoos received in prison with hepatitis B and C positivity among street-recruited injecting drug users in New Mexico, USA. Epidemiol Infect. 2001;127:475–84. doi: 10.1017/s0950268801006197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellard M, Hocking J, Crofts N. The prevalence and the risk behaviours associated with the transmission of hepatitis C virus in Australian correctional facilities. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:409–15. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803001882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babudieri S, Longo B, Sarmati L, Starnini G, Dori L, Suligoi B, et al. Correlates of HIV, HBV, and HCV infections in a prison inmate population: Results from a multicentre study in Italy. J Med Virol. 2005;76:311–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zakizad M, Salmeh F, Yaghoobi T, Yaghoubian M, Nesami M, Esmaeeli Z, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C infection and associated risk factors among addicted prisoners in Sari-Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12:1012–8. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2009.1012.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]