Abstract

Objectives:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the major cause of post-transfusion hepatitis infection (PTH). Patients with thalassemia major are at high risk of hepatitis C due to the blood transfusion from donors infected by HCV. The aim of this study was to detect the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies and risk factors in multitransfused thalassemic patients in Isfahan-Iran to establish more preventive strategies.

Methods:

This study was conducted to assess the patients with beta-thalassemia in Isfahan hospitals during 1996-2011 for HCV infection. A structured interview questionnaire was developed by the trained researcher to collect the demographic and risk factors. Statistical analysis was done by Chi-square test, Mann-Withney and multiple logistic regressions using SPSS software, version 15.

Results:

466 patients with major thalassemia participated in this study. The mean age of patients was 17.46 ± 8.3. Two hundred and seventy (58.3%) and 193 (41.7%) of participants were male and female, respectively. The prevalence of HCV was estimated 8% among thalassemia patients. History of surgery, history of dental procedure, number of units transfused per month, number of transfusion per month and duration of transfusion had significant association with HCV seropositivity in univariate analysis. There were no statistical significant risk factors for HCV seropositivity in multiple logistic regression models.

Conclusions:

Our findings revealed that blood transfusion was the main risk factors for HCV infection among beta-thalassemic patients. Therefore, more blood donor screening programs and effective screening techniques are needed to prevent transmission of HCV infection among beta-thalassemic patients.

Keywords: Beta-thalassemia, HCV infection, Iran

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the major cause of post-transfusion hepatitis infection (PTH). The virus infects liver cells and causes severe inflammation in liver with long-term problems.[1] Infection with HCV may lead to disabling symptoms, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.[2,3] It is said that from 2010–2019, HCV may cause to the loss of 1.83 million years of life among people less than 65 years of age.[4] WHO studies show that, 170 million of people are infected by HCV in the world.[5]

Thalassemia is an inherited disorder. Patients with thalassemia major are at high risk of hepatitis C due to the blood transfusion from donors infected by HCV.[6] Although, improvement in screening of blood products from 1980 to 1990 decreased the risk of transmission of blood-borne diseases, however, hepatitis C is still remained as an important problem in patients with thalassemia.[7,8] Chronic post transfusion hepatitis C lead to hepatocellular necrosis, fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with thalassemia and accepted as an important cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients.[9]

Iran has a high thalassemia carrier rate because it is located in the middle of the thalassemia belt.[10] It is documented that prevalence of HCV infection is higher among Iranian patients with beta-thalassemia as compared with HBV and HIV.[11]

In Iran, since 1995 routine screening for blood born diseases has been mainly conducted among blood and tissue donors and due to this program, prevalence of HCV in thalassemic patients decreased, significantly.[12]

Previous studies in Iran have reported the prevalence of HCV in beta-thalassemia patient at a wide range of 7-64%.[11]

According to limited information about sero-prevalence and associated factors of HCV infection in thalassemia patients in Isfahan, this study conducted to detect the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies and risk factors in these patients in Isfahan-Iran to establish more preventive strategies.

METHODS

This study was conducted to assess the patients with beta-thalassemia in Isfahan hospitals during 1996-2011 for HCV infection. A structured interview questionnaire was developed to collect the demographic and risk factors of hepatitis C including gender, age, marital status, job, education, surgical history, dentistry history, illegal sex, tattooing, cupping, piercing, prison history, duration of transfusion, number of units transfused per month and number of transfusion per month.

Interview was done by one member, who was educated and reliable with study participants after obtaining informed consent. Face and content validity of questionnaire was accepted by 10 expert persons. Questionnaire reliability was carried out by Chronbach Alpha.

Participation to study was voluntary for patients and the name of participants remained unknown. This study was approved by Ethical Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

The collected data was coded and entered in a data base file. After complete entry, data were transferred to the SPSS software version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The Chi-square test for categorical variables and nonparametric Mann-Withney test for quantitative variables were used to find significant associations between patient's characteristics and HCV positivity. Multiple logistic regression models were applied to estimate adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for risk factors of HCV positivity. Statistical tests were conducted at the P < 0.05 significance level.

RESULTS

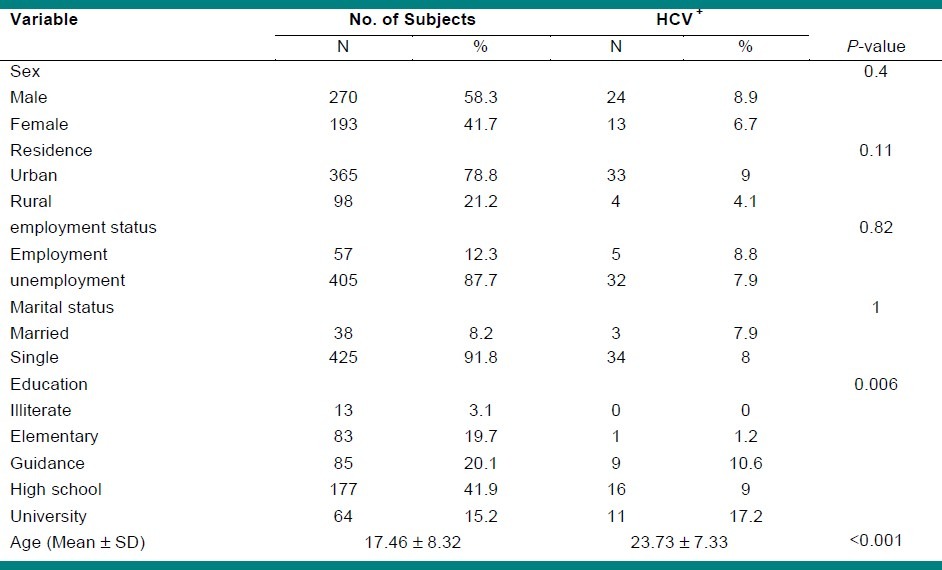

Four hundred and sixty six patients with major beta-thalassemia enrolled in this study. The mean age of patients was 17.46 ± 8.3. Two hundred and seventy (58.3%) and 193 (41.7%) of participants were male and female, respectively. Most of the participants had no job (87.7%) [Table 1]. The prevalence of HCV was 8% among the participants.

Table 1.

Univariate association between demographic characteristics and HCV seropositivity

As seen in Table 1, education and age had significant univariate association with HCV seropositivity.

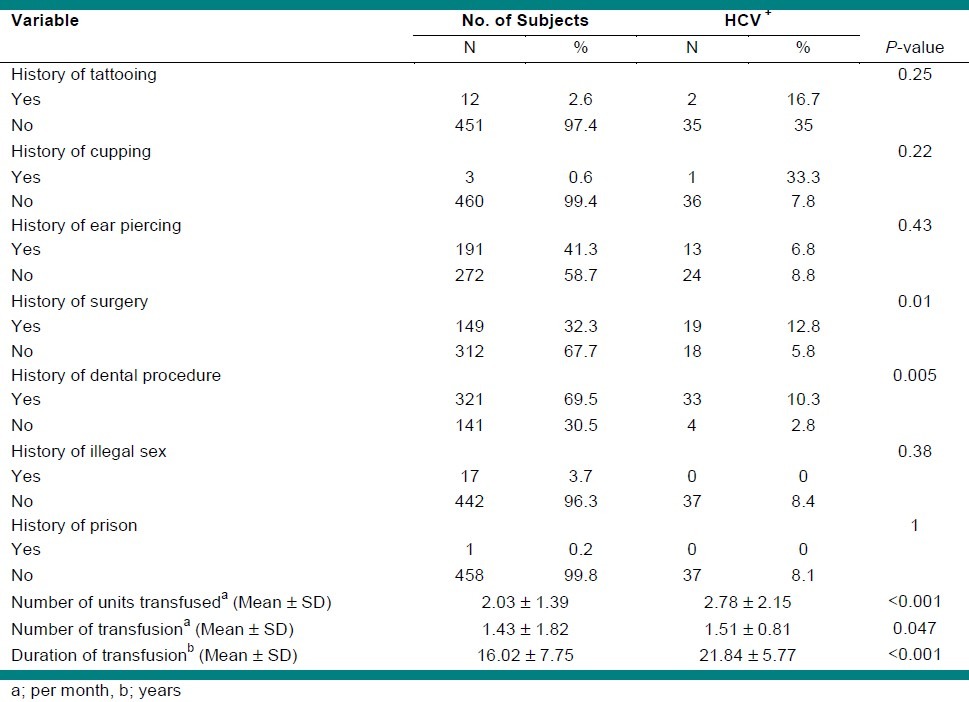

Table 2 described frequency and univariate association of some risk factors of HCV positivity. History of surgery, dental procedure, number of units transfused per month, number of transfusion per month and duration of transfusion were significant correlated variables with HCV prevalence.

Table 2.

Univariate association between potential risk factors and HCV seropositivity

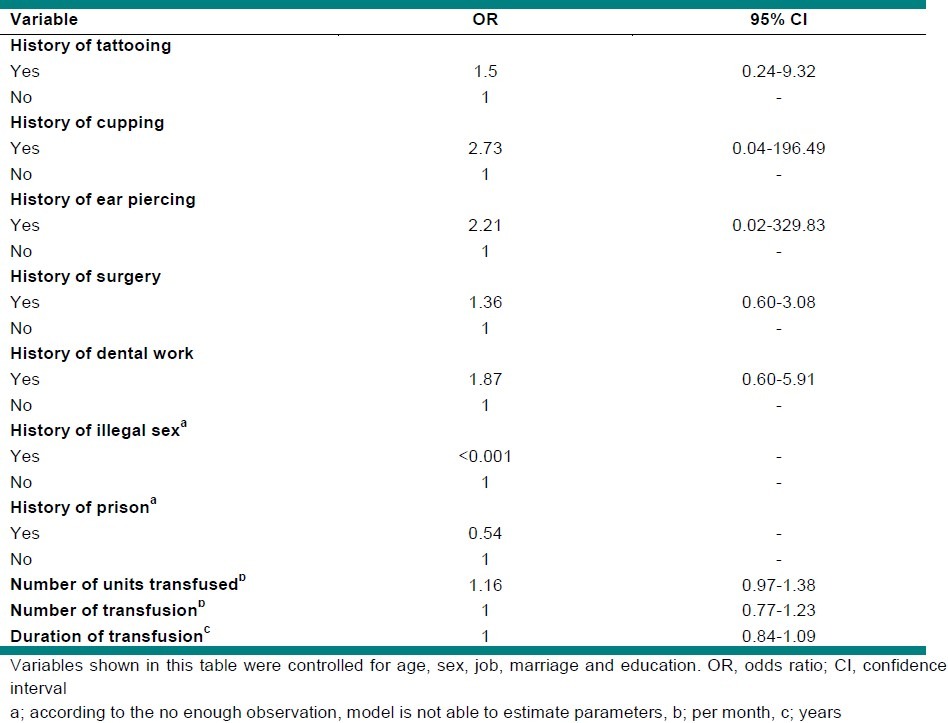

According to the multiple logistic regression model, there were no statistical significant risk factors for HCV seropositivity [Table 3].

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression of potential risk factors for HCV seropositivity

DISCUSSION

In this study, we revealed that 8% of beta-thalassemic patients were HCV infected. Previous studies on Iranian beta-thalassemic patients reported a wide range of 7-64% for HCV prevalence.[11] Alavi et al.[12] in Tehran showed the prevalence of HCV positive in beta-thalassemic patients as 11% in 2005. In Kerman, the prevalence was 31%.[10] It has been reported 64% in Rasht,[13] 28.1% in Khuzestan,[14] 25% in Shiraz,[15] 9% in Yazd,[16] 40% in Semnan,[17] 17% in Mazandaran,[18] 13% in Sistan and Baluchistan,[19] and 7% in Markazi[20] as well.

Therefore, the rate we found in this study does not appear to be very high, when compared with the HCV infection prevalence among beta-thalassemic patients in other provinces in Iran.

It can be due to our patients were transfused at the thalassemia management center of Seyed o Shohada hospital, where pre-transfusion screening of the transfused is regularly performed.

In 2006, Hariri et al.[21] in Isfahan revealed that the prevalence of HCV positive among thalassemic patients is 11%. In comparison with our study that reports prevalence of 8%, there is significance reduction in last 5 years.

The other studies from some countries reported an HCV infection rate of 40.5% in Jordan,[22] 30% in India,[23] 35% in Pakistan[24] and 33% in Kuwait.[25]

The reason of this wide range can be due to difference in type and sensitivity of testes, the prevalence of HCV in the relevant population and the time of screening. In comparison with other developing countries, the prevalence of HCV infection among beta-thalassemic patients is lower in Iran. The countries with a higher HCV prevalence in general population had a higher prevalence rate among thalassemia patients, too. For instance, in a study in Egypt the prevalence of HCV among thalassemic patients has been reported as 75% considering the fact that the prevalence in their blood donor population was 14.5%.[26] In Iran, HCV infection prevalence in general population is estimated to be less than 1%.[27] Furthermore, introduction of tests for screening of blood donors after 1995 has markedly reduced the risk of HCV transmission through blood product transfusion in our country.

This study also evaluated risk factors for HCV infection among beta-thalassemic patients. The results of univariate analysis demonstrated history of surgery, history of dental procedure, number of units transfused per month, number of transfusion per month and duration of transfusion had significant association with HCV seropositivity.

In accordance with other studies,[14,28] in this study mean age ± SD (23.73 ± 7.33) was significantly higher in patients with positive HCV-Ab compared to negative patients (17.46 ± 8.32). The results of our study showed HCV positive patients had a significantly more number of units transfused and more number of transfusion per month. These findings are in agreement with some earlier studies.[13,14,28–29] In addition, similar to other HCV seroprevalence studies among beta-thalassemic patients,[13,14] we found HCV positive patients had a significantly longer duration of transfusion compared with HCV negative cases.

Our findings highlighted blood transfusion as the main risk factors for HCV infection among beta-thalassemic patients. The higher rate of HCV infection in older patients, as well as patients with more number of units transfused, more number of transfusions per month and longer duration of transfusion display the importance of providing safe blood to decrease the incidence of HCV infection in thalassemia population and confirm the important role of blood donors screening in the prevention of viral transmission[30].

Remarkably, in our study history of surgery and dental procedure had significant association with HCV prevalence that has not been found in previous studies. Differences in quality of hospital care and health facilities or differences between education and training could attribute to difference in results.

In conclusion, beta-thalassemic patients are at risk of acquiring HCV infection and progression to liver failure and hepatocellular cancer. Therefore, blood donor screening protocol and effective screening techniques are likely to be needed to prevent speared of HCV infection among beta-thalassemic patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board. Hepatitis A, B and C: Defining workers at risk. Viral Hepat. 1995:3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong MJ, El-Farra NS, Reikes AR, Co RL. Clinical outcomes after transfusion-associated hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1463–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.di Bisceglie AM, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, Hoofnagle JH, Melpolder JJ, Alter HJ. Long-term clinical and histopathological follow-up of chronic post-transfusion hepatitis. Hepatology. 1991;14:969–74. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(91)90113-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong JB, McQuillan GM, McHutchison JG, Poynard T. Estimating future hepatitis C morbidity, mortality, and costs in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1562–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global surveillance and control of hepatitis C. Report of a WHO Consultation organized in collaboration with the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board, Antwerp, Belgium. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:35–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal M, Malkan G, Bhave A, Vishwanathan C, Billa V, Dube S, et al. Antibody to hepatitis-C virus in multi-transfused thalassaemics--Indian experience. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993;41:195–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ocak S, Kaya H, Cetin M, Gali E, Ozturk M. Sero-prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in patients with thalassemia and sickle cell anemia in a long-term follow-up. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:895–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prati D, Maggioni M, Milani S, Cerino M, Cianciulli P, Coggi G, et al. Clinical and histological characterization of liver disease in patients with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia. A multicenter study of 117 cases. Haematologica. 2004;89:1179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angelucci E, Pilo F. Treatment of hepatitis C in patients with thalassemia. Haematologica. 2008;93:1121–3. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abolghasemi H, Amid A, Zeinali S, Radfar MH, Eshghi P, Rahiminejad MS, et al. Thalassemia in Iran: Epidemiology, prevention, and management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;29:233–8. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3180437e02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirmomen S, Alavian SM, Hajarizadeh B, Kafaee J, Yektaparast B, Zahedi MJ, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus infecions in patients with beta-thalassemia in Iran: A multicenter study. Arch Iran Med. 2006;9:319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alavi S, Arzanian M, Hatami K, Shirani A. Frequency of hepatitis C in thalassemic patients and its association with liver enzymes, Mofid hospital, Tehran, 2002. J Shaheed Beheshti Univ Med Sci. 2005;29:213–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansar M, Kooloobandi A. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in thalassemia and haemodialysis patients in north Iran‐Rasht. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:390–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boroujerdnia MG, Zadegan MA, Zandian KM, Rodan MH. Prevalence of hepatitis-C virus (HCV) among thalassemia patients in Khuzestan Province, Southwest Iran. Pak J Med Sci Q. 2009;25:113–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akbari A, Imanieh MH, Karimi M, Tabatabaee HR. Hepatitis C virus antibody positive cases in multi-transfused thalassemic patients in South of Iran. Hepat Mon. 2007;7:63–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Javadzadeh H, Attar M, Yavari MT, SAVABIEH S. Study of the prevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV infection in hemophilia and thalassemia population of Yazd. Khoon) 2006;2:315–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faranoush M, Ghorbani R, Amin-Bidokhti M, Vosoogh P, Malek M, Yazdiha M. Prevalence of Hepatitis C resulted from blood transfusion in major Thalassemia patients in Semnan, Damghan and Garmsar, 2002. J Hormozgan Univ Med Sci. 2006;1:82–77. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ameli M, Besharati S, Nemati K, Zamani F. Relationship between elevated liver enzyme with iron overload and viral hepatitis in thalassemia major patients in Northern Iran. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:1611–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanei-Moghaddam E, Savadkoohi S, Rakhshani F. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C in patients with major Beta-thalassaemia referred to Ali-Asghar hospital In Zahedan, 2002. Blood Sci J Iran. 2004;1:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahdaviani F, Saremi S, Rafiee M. Prevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in thalassemic and hemophilic patients of Markazi province in 2004. Blood Sci J Iran. 2008;4:313–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Sheyyab M, Batieha A, El-Khateeb M. The prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immune deficiency virus markers in multitransfused patients. J Trop Pediatr. 2001;47:239–42. doi: 10.1093/tropej/47.4.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irshad M, Peter S. Spectrum of viral hepatitis in thalassemic children receiving multiple blood transfusions. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2002;21:183–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehman M, Lodhi Y. Prospects of future of conservative management of β-thalassemia major in a developing country. Pak J Med Sci. 2004;20:105–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Fuzae L, Aboolbacker KC, Al-Saleh Q. Betathalassemia major in Kuwait. J Trop Pediatr. 1998;44:311–2. doi: 10.1093/tropej/44.5.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Gohary A, Hassan A, Nooman Z, Lavanchy D, Mayerat C, El Ayat A, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus among urban and rural population groups in Egypt. Acta Trop. 1995;59:155–61. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(95)00075-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alavian SM, Ahmadzad-Asl M, Lankarani KB, Shahbabaie MA, Bahrami Ahmadi A, Kabir A. Hepatitis C infection in the general population of Iran: A systematic review. Hepat Mon. 2009;9:211–23. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alavian SM, Tabatabaei S, Lankarani K. Epidemiology of HCV infection among thalassemia patients in eastern Mediterranean countries: A quantitative review of literature. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2010;12:365–76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamaddoni A, Mohammadzadeh I, Ziaei O. Sero-prevalence of HCV antibody among patients with β-thalassemia major in Amirkola Thalassemia center, Iran. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;6:41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shahraki T, Shahraki M, Moghaddam ES, Najafi M, Bahari A. Determination of Hepatitis C Genotypes and the Viral Titer Distribution in Children and Adolescents with Major Thalassemia. Iran J Pediatr. 2010;20:75–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kassaian N, Nokhodian Z, Babak A, Ataei B, Adibi P. Hepatitis C in patients with multi Blood transfusion. JIMS. 2011;28:1560–1564. [Google Scholar]