Abstract

Objectives:

Patients with hereditary bleeding disorders are at risk of viral infection such as hepatitis C due to frequent transfusion of blood and blood products. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of hepatitis C and associated risk factors in hemophilic patients in Isfahan, the second big province in Iran.

Methods:

In a descriptive study, patients with hemophilia in Isfahan province were enrolled. A questionnaire, including demographic and risk factors of hepatitis C was completed through a structured interview with closed questions by a trained interviewer for each patient and HCV-Ab test results were extracted from patient records.

Results:

In this study, 232 of 350 patients with hemophilia A and B (66%) were positive for hepatitis C. Based on Multivariate Logistic Regression model, no independent risk factor was found.

Conclusions:

Prevalence of hepatitis C in patients with haemophilia A and B in Isfahan is high. Since no independent risk factor for hepatitis C disease was found in this high risk group, it can be concluded that multitransfusion is the only predictor for hepatitis C.

Keywords: Hemophilia, Hepatitis C, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

HCV infection considered as an important health problem, worldwide. It is estimated that 170 million people are infected with HCV.[1] HCV infection has become the cause of the second major epidemic of viral infection after human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It can progress to chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Chronic hepatitis C is the second common cause of end-stage liver disease and the leading cause of liver transplants in Iran and many countries.[2,3]

Though it is estimated that the incidence of new HCV infection would be decreased over the next decade but its related mortality and costs will increase due to its longterm complications.[4,5]

HCV infection considered the most important cause of morbidity and mortality in multiply transfused patients due to hereditary bleeding disorders. Most of the patients with mentioned disease have been infected during receiving clotting factors before the introduction of virus-inactivation methods. The rate of infection decreased significantly after implementation of compulsory blood donors screening in Iran in 1997.[6,7]

Evidences indicated high prevalence of HCV infection among hemophilic patients and the risk of acquisition of HCV infection is higher in hemophilic than patients with other hereditary bleeding disorders. HCV seropositivity was significantly associated with longer history of transfusion. The prevalence of HCV infection has reported to be 15.6-76.7% among Iranian hemo-philic patients.[8,9]

Advances in factor replacement therapy and management of the disease especially appropriate treatment of infectious diseases led to improvement in the overall life expectancy and quality of life of hemophilic population. But this group of patients encounter many challenges which is not directly related to hemophilia.HCV infection considers one of these challenging factors due to its related complications such as increased risk of developing end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma.[9]

Considering that understanding the epidemiology of the infection and its related factors, would be useful in planning more effective programs for controlling the disease and its related complication, the aim of current study was to determine the prevalence of hepatitis C and associated risk factors in these patients in Isfahan, the second big province in Iran.

METHODS

In this cross sectional, descriptive study, patients with hemophilia A and B, diagnosed, treated and registered from 1996-2010, in Isfahan Hemophilic Society, were enrolled. The patients refer to Seyedolshohada hospital, affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical sciences, for follow up.

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Isfahan Infectious and Tropical Disease Research Center and Medical Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient with the assurance that all obtained information would be just for research purposes and would be remained confidential.

A questionnaire, including demographic and risk factors of hepatitis C was completed through a structured interview with closed questions by a trained interviewer for each patient and HCV-Ab test results were extracted from patient records.

Content validity and reliability of the questionnaire was approved by 10 experts and Cronbach's alpha 0.78, respectively.

Obtained data analyzed using SPSS (ver 15, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Multivariate Logistic Regression model was used to determine the independent risk factor for HCV infection.

RESULTS

In this study 350 (342 men and 8 women) patients with hemophilia A and B studied.

Median age of the patients and the duration of the disease were 24 (<1-60) and 20 (1-44), respectively. Among the participants, 5.3% had high risk sex behaviours and nobody had IDU history. Mean of injected blood product frequency and unit of blood products as units/month were 5.7 +/–6.4 times/month and 8.2 +/–9.3 unit /month, respectively. 231 patients (66%) were HVV infected.

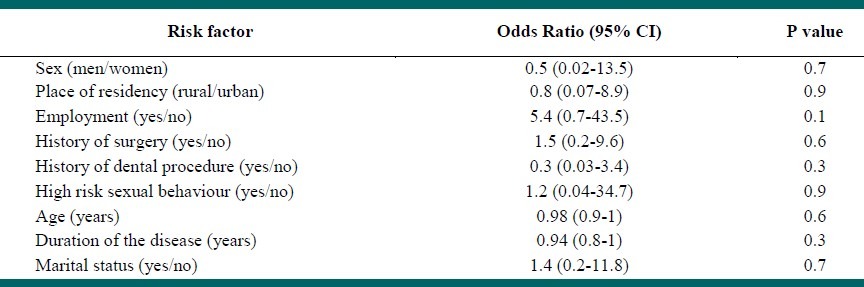

Based on Multivariate Logistic Regression model, no independent risk factor was found, Table 1.

Table 1.

Adjusted risk factors for HCV infection among hemophilic patients in Isfahan

CONCLUSION

In this study the prevalence of HCV infection among hemophilic patients of Isfahan province was determined. The findings indicated that 66% of our studied population was positive for anti-HCV antibody and there was not any independent risk factor for hepatitis C disease from studied risk factors. The findings indicated the role of multitranfusion in HCV infection among this high risk population.

Many studies have investigated the prevalence of HCV infection in hemophilic patients in Iran and worldwide. The reported prevalence of HCV infection varied in different cities in Iran and different countries in the world.

The prevalence of HCV infection in Iran ranged between 29%-83.3% in different cities or province of Iran. The lowest rate was in Zahedanand the highest in Tehran.[10–12]

The prevalence of HCV infection in different countries was varied also. The rate of HCV infection was similar to ours in one study in Brazil (63.3%) and Canada (63%). It was lower in Pakistan (36%) and higher in United Kingdom (76%), the USA (89.3%) and New Zeland (89.6%).[13–18]

The difference observed in different populations may be due to laboratory methods and selection methods.

Though HCV infection considered as an important issue among patients with congenital bleeding

disorders who need to receive regular blood products, but studies showed that the rate of infection is higher in hemophilic patients because of the frequent use of blood products and improving the life expectancy of the disorder, so in this research we determine HCV infection rate among hemophilic patients of Isfahan province.

In another study in Isfahan city, the rate of infection reported to be 22.6%.They concluded that using of FFP has less chance for HCV infection than cryoprecipitate.[19]

In a recent study in Tehran, Mousavian and colleagues[20] have reviewed the files of 1170 hemophilic patients in Iranian Hemophilia Society center in Tehran from 2003 to 2005 and showed that 802 (72.3%) of patients had positive anti-HCV antibody. They emphasize on the screening of hemophilic patients for HCV infection.

In current study we did not find any independent risk factor for hepatitis C infection and it seems that multitranfusion is the most important risk factor in this regard. Our results were similar to the results of Mojtabavi et al, in Isfahan and some other studies in Iran and other countries.[9,19,21] Whereas others have indicated the role of other factors such as age.[22]

The limitation of this study was that we did not determine the genotype of HCV infection among infected patients. Distribution of HCV genotype indicate the origin of infection and predict the treatment response.[23] Previous studies conducted by Keshvari et al,[24] showed that genotype 1a following by 3a and 1b are the most prevalent HCV genotypes among Iranian hemophilic patients which was similar to Western Europe and different from Middle East region.

In conclusion, our results indicated the high rate of HCV infection among hemophilic patients of Isfahan province. These results would be informative for planning future studies regarding screening of HCV infection in this high risk population and treatment protocols among them. However controlling the HCV infection among this high risk population would reduce the rate of the infection in whole community. Considering the fact that most of the infected hemophilic patients in developed countries are at cirrhotic phase but in developing countries such as Iran infected hemophilic patients have milder liver damage,[24,25] the findings of current study would be useful in early diagnosis and treatment of the infection, improving the quality of life of hemophilic patients and consequently in decreasing the burden of HCV infection and its related morbidity and mortality in our community, rate of nasocomial and intra-familial transmission.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health organization Hepatitis C. WHO fact sheet No 164. [Last accessed on 2012]. Available from: http://www.Whoint/inffs/en/fact 164 htm .

- 2.Sy T, Jamal MM. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3:41–6. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Saadany S, Coyle D, Giulivi A, Afzal M. Economic burden of hepatitis C in Canada and the potential impact of prevention.Results from a disease model. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6:159–65. doi: 10.1007/s10198-004-0273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Panel statement: management of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26(3Suppl 1):2S–10S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burattini M, Massad E, Rozman M, Azevedo R, Carvalho H. Correlation between HIV and HCV in Brazilian prisoners: evidence for parenteral transmission inside prison. Rev Saude Publica. 2000;34:431–6. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102000000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhubi B, Mekaj Y, Baruti Z, Bunjaku I, Belegu M. Transfusion-transmitted infections in haemophilia patients. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2009;9:271–7. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2009.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Editorial: Zendegi (Iran Hemophilia Society Quarterly) 1997;3:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alavian SM, Ardeshiri A, Hajarizadeh B. Seroprevalence of anti-HCVAb among Iranian hemophilia patients. Transfusion Today. 2001;49:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alavian SM. Prevalence of HCV, HBV and HIV infection among hemophiliacs patients. Hakim Res J. 2003;6:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharifi-Mood B, Eshghi P, Sanei-Moghaddam E, Hashemi M. Hepatitis B and C virus infections in patients with hemophilia in Zahedan, southeast Iran. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:1516–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahedi MJ, Darviesh Moghaddam S. Assessment of prevalence of hepatitis B and C in hemophilic patients in Kerman in 1383. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2008;3:131–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.NassiriToosi M, Lak M. Seroprevalence of Human Immunodificiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C Infection in Hemophilic Patients in Iran. Iran J Pathol. 2008;3:119–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbosa AP, Martins RM, Teles SA, Silva SA, Oliveira JM, Yoshida CF. Prevalence of hepatitis C Virus infection amonghemophiliacs in Central Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:643–4. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchette V, Walker I, Gill P, Adams M, Roberts R, Inwood M. Hepatitis C infection in patients with hemophilia: Results of a national survey 1994. Transfus Med Rev. 1994;8:210–7. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(94)70112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naghmi A, Tahira Z, Khalid H, Lubna N. Seroprevalence Anti HCV Antibodies, HCV- RNA and its Genotypes among Patients of Hemophilia, at Hemophilia Treatment Centre Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences, Islamabad. Int J Pathol. 2009;7:84–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Troisi CL, Hollinger FB, Hoots WK, Contant C, Gill J, Ragni M, et al. A multicenter study of viral hepatitis in a United States hemophilic population. Blood. 1993;81:412–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson SR, Carter JM, Jackson TW, Green GJ, Hawkins TE, Romeril K. Hepatitis C seroprevalence in bone marrow transplant recipients and haemophiliacs. N Z Med J. 1994;107:10–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed MM, Mutimer DJ, Elias E, Linin J, Garrido M, Hubscher S, et al. A combined management protocol for patients with coagulation disordersinfected with hepatitis C virus. Br J Haematol. 1996;95:383–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mojtabavi Naini M, Derakhshan F, Hourfar H, Derakhshan R, Makarian Rajab F. Analysis of the Related Factors in Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among Hemophilic Patients in Isfahan, Iran. Hepat Mon. 2007;7:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mousavian SA, Mansouri F, Saraei A, Sadeghei A, Merat S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C in hemophilia patients refering to iran hemophilia society center in Tehran. Govaresh. 2011;16:169–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brettler DB, Alter HJ, Dienstag JL, Forsberg AD, Levine PH. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody in a cohort of hemophilia patients. Blood. 1990;76:254–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva LK, Silva MB, Lopes GB, Rodart IF, Costa FQ, Santana NP, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and HCV genotypes among hemophiliacs in the State of Bahia, Northeastern Brazil: analysis of serological and virological parameters. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:496–502. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822005000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chevaliez S, Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus: Virology, diagnosis and management of antiviral therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2461–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keshvari M, Alavian SM, Behnava B, Miri SM, Karimi Elizee P, Tabatabaei SV, et al. Distribution of Hepatitis C Virus Genotypes in Iranian Patients with Congenital Bleeding Disorders. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2010;12:608–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassaian N, Nokhodian Z, Babak A, Ataei B, Adibi P. Hepatitis C in patients with multi blood transfusion. Journal of isfahan Medical School. 2011;28:1564–70. [Google Scholar]