Abstract

Background:

Constipation is physically and mentally troublesome for many patients and has adverse effects on their quality of life. The aim of the present study was to systematically review previous studies on the epidemiology of constipation in Iran.

Methods:

Bibliographic databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, and Iranian databases including Scientific Information Database, Iran Medex, and Magiran were searched to select studies that reported the prevalence of constipation in Iran.

Results:

Overall, 10 articles met the inclusion criteria of the current study. The prevalence of constipation in Iran ranged from 1.4-37%, and the prevalence of functional constipation was reported to be 2.4-11.2%. Gender, age, socioeconomic status and educational level seem to have major effects on this condition.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of constipation is high in Iran. There are very few data available regarding the natural history, quality of life and risk factors of constipation in our country. Conducting population-based studies is necessary to explore different epidemiological aspects of constipation in Iran.

Keywords: Constipation, epidemiology, Iran, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) include a variety of symptom-based conditions, which cannot be adequately explained by organic findings. FGIDs affecting the lower gastrointestinal tract include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional constipation, functional bloating, functional diarrhea and unspecific functional bowel disorders.[1] Functional constipation is a common bowel disorder and presents as “persistently difficult, infrequent, or incomplete defecation”, which does not meet the criteria to be considered as IBS. Functional constipation occurs in up to 27% of the general population and affects all age groups, but seems to be more prevalent in women than men.[2]

Previous studies investigating the prevalence of functional constipation have reported a wide range of prevalence rates, which is a result of differences in the definition of criteria used, sampling methods, and the studied populations. The prevalence of constipation in North America ranged from 1.9% to 27.2%.[2,3] In one systematic review, in the general population of Europe and Oceania, the mean value of the reported constipation rates were 17.1% and 15.3%, respectively.[4] In a Canadian survey, employing the Rome I and Rome II criteria, the prevalence of functional constipation was reported to be 16.7% and 14.9%, respectively.[5] In a systematic review in China, functional constipation had a prevalence of 6% and was more prevalent among women.[6] In a population–based study on bowel habits in Korea, the prevalence was 16.5% for self-reported constipation and 9.2% for functional constipation. The prevalence of constipation was observed to increase with age and decrease with higher levels of education and economic status.[7]

The impact of constipation on the quality of life may vary across nations but is generally believed to be of high significance. According to a multinational survey carried out in France, Germany, Italy, UK, South Korea, Brazil and USA, Brazilians had the highest prevalence of constipation which was considered to be due to their “social functioning and general health perception”.[8]

The prevalence of constipation and functional constipation was estimated to be 2.4%-11% in Tehran.[9–12] In a study conducted by Adibi et al. in Isfahan, the prevalence of constipation was reported to be 32.9%.[13] In Tabriz, located in northwest of Iran, the prevalence of constipation was 3.6%[14] but it was 27% in the victims of the catastrophic earthquake of Bam.[15]

Because of its high prevalence and strong impact on the quality of life, productivity and resources, the burden of FGIDs seems to be relatively high in developing countries such as Iran.[16–18] In a cross-sectional population-based study in Iran, the mean of 6-months-total medical expenses was estimated to be approximately 147 PPP$ for functional constipation (purchasing power parity dollars).[17] Total costs per year of IBS and functional constipation for the urban adult population of Iran was roughly estimated at 2.94 billion PPP$ and 89.2 million PPP$, respectively, in a burden analysis study .[18]

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review investigating the epidemiology of constipation and functional constipation in Iran. In addition, this review provides background knowledge for the “Study on the Epidemiology of Psychological, Alimentary Health and Nutrition” (SEPAHAN).[19] The data of SEPAHAN will explore the epidemiology of FGIDs in the Isfahan province and will be published later by the same study group.

METHODS

This was a systematic review study investigating all published studies on the epidemiology of constipation in Iran.

Search strategy and citations library

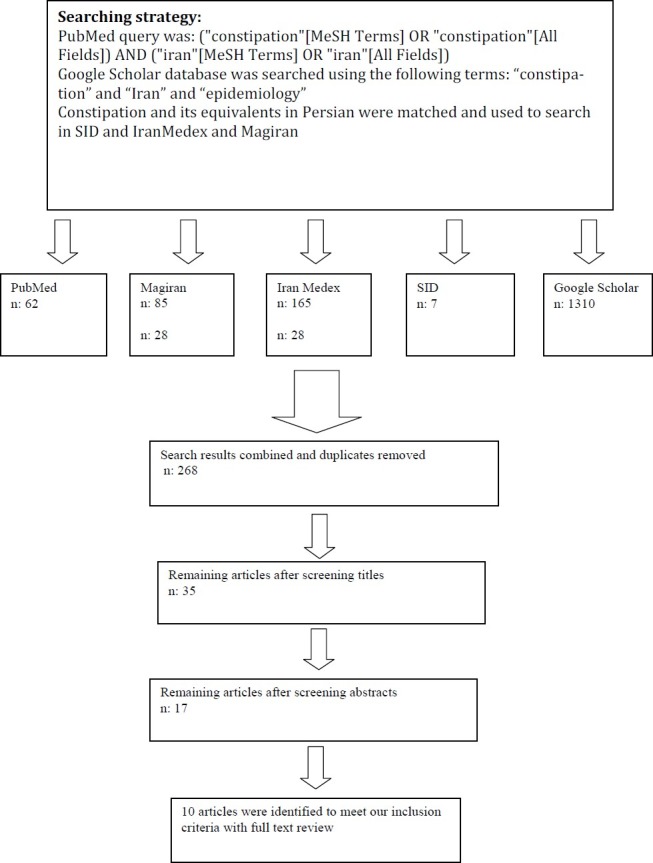

In March 2012, we used a computer-assisted searching method to identify articles in five electronic bibliographic databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, Scientific Information Database (www.sid.ir), IranMedex (www.iranmedex.com), and Magiran (www.magiran.com). The three latter databases were searched, to find articles published in local journals. Reference lists of potentially relevant articles were also hand-searched to identify additional articles. Details of the key words used to search the above mentioned databases are presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram of search strategies and screening for articles to be included in the systematic review of constipation in Iran

Study selection criteria

Two reviewers conducted the primary review and study selection. First, the titles of all collected articles were reviewed and those related to the subject were selected. Then, abstracts of the selected articles were reviewed, and relevant articles were selected to have their full texts retrieved and reviewed in the next step. Those articles that fulfilled the following selection criteria were included in our study: 1) Presenting an estimation of constipation prevalence, 2) Conducted in an adult age group, and 3) Published in full manuscript form. Studies conducted in highly selective populations (e.g. medical conations) were excluded (Figure 1).

Data extraction

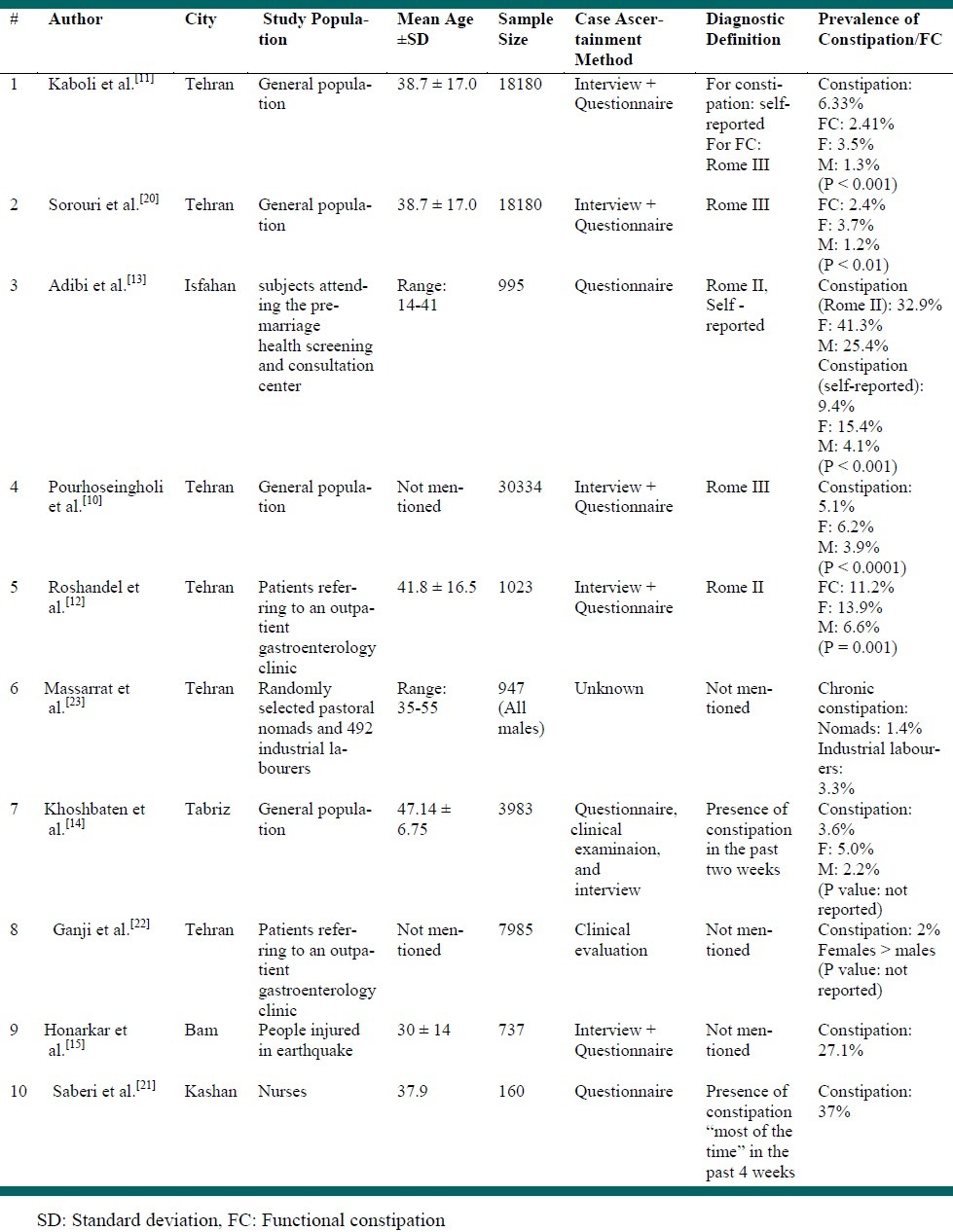

Eligible articles were reviewed by two reviewers. From these studies, data on the prevalence of reported constipation, gender distribution, and the mean age of the study population were extracted, if available. Data on the district of the study, diagnostic definition and criteria used, study population, sample size, and case ascertainment methods to define constipation and demographic factors were also extracted (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of constipation and functional constipation in Iranian studies

RESULTS

In our research, using specific key words and the above-mentioned method, 1629 articles were identified in PubMed, Scientific Information Database, IranMedex, Google Scholar and Magiran (Figure 1). A number of articles were indexed in two or more of the searched databases, but only one version of these articles was included in this review. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 10 studies were found to fulfill the selection criteria.[10–15,20–23] Although two articles represented an identical study, we had to include them in the present review as the prevalence of constipation was reported in one article[11] and the prevalence of functional constipation was reported in both articles.[11,20]

Three of the 10 included studies used the Rome II criteria,[[12–[14] and four employed the Rome III criteria[10,11,20] for the diagnosis of constipation. In four studies, no definition or criteria was mentioned for the diagnosis of constipation.[15,21–23] The reported prevalence ranged from 1.4% to 37% for constipation and 2.4% to 11.2% for functional constipation.[10–15,20–23] Massarrat et al. who conducted a survey on constipation in pastoral nomads and industrial labourers reported a prevalence of 1.4% in nomads and 3.3% in industrial labourers.[23] Saberi et al. reported the prevalence of constipation to be 37% among hospital personnel.[21] In most Iranian studies the prevalence of constipation was higher amongst women than men.[10–14,22]

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review identified 10 studies that reported the prevalence of constipation according to available data collected from different provinces in Iran. The prevalence of constipation in Iran ranged from 1.4% to 37% and the prevalence of functional constipation ranged from 2.4% to 11.2%.[10–15,20–23]

The prevalence of constipation in the general worldwide population, is stated to range from 0.7% to 79%.[24] Constipation is generally less prevalent in Iran, compared to the western countries. One possible reason for the lower prevalence of functional constipation in Iran compared to western countries could be the architecture of Iranian toilets that allows more flexing of the hip joints. Full flexion of the hips stretches the anal canal in an antero-posterior direction and straightens the anorectal angle, which in turn promotes the emptying of the rectum.[25] Moreover, several dietary factors such as the higher consumption rate of vegetables and fruits by Iranians could be the cause of the lower prevalence of constipation.[26]

The results of this review showed remarkable differences between the prevalence of constipation in men and women. In the majority of the studies, the prevalence of constipation was higher in the female gender. This is in accordance with a review conducted in North America; which reported the prevalence of constipation to be consistently higher in women.[27] Factors that may contribute to higher constipation rates in females include the fact that women are more likely to report the symptoms, and that they tend to respond to surveys more than men. Additionally, women are at a higher risk of injury to the pelvic floor muscles and nerves.[27–30] The effect of sex hormones in promoting GI motility and the autonomic nervous system may also be the reason of the female predominance in constipation.[13,28] Some studies have focused on female sex hormones, because in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, when plasma progesterone levels rise, gastrointestinal transit time elevates.[31,34]

Age effects on the prevalence of constipation were frequently reported in Iranian studies. The prevalence of anatomic abnormalities, such as rectocele, rectal intussusceptions or prolapse, or pelvic floor dyssynergia, is higher in the older population, and this is suggested to contribute to constipation symptoms. The higher prevalence of constipation in the elderly might also be due to the lower dietary and energy intake. A low dietary intake, leads to reduction of the fecal volume and weight, and hence causes constipation. Multiple medication use might be another explanation.[27] In the study conducted by Adibi et al. however, there was no report of a significant difference regarding the age of participants. This could be due to the fact that their study recruited young adults.[13]

An increased prevalence of constipation was found to be in correlation with low socioeconomic status and low educational levels in several studies. The differences in constipation rates by educational level could be due to differences in dietary habits.[11]

There are other factors that have been reported in Iranian studies. Honarkar et al. showed that anorexia, early satiety, distention and constipation were significantly more prevalent among patients with major fractures including: pelvic and limb fractures. They also demonstrated a significant association between the severity of physical injury, and the prevalence and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms.[15] In the study conducted by Kaboli et al. a greater percentage of obese individuals were observed to have functional constipation, compared to non-obese subjects.[11] In a study in the US on the other hand, no significant relation was found between body mass index (BMI) and constipation; although constipation was somewhat more frequent in obese patients.[35] Saberi et al. demonstrated that, in a population of nurses in Iran, the prevalence of GI symptoms was higher in shift-work nurses compared with day-working nurses.[20] Their finding is in agreement with previous studies.[36,37]

The wide range of the prevalence rates reported in Iranian studies is most likely the result of different demographic factors, sampling methods, and diagnostic definitions employed in these studies.[2] For instance, the study of Massarrat et al. on two populations of pastoral nomads and industrial labourers resulted in the report of a prevalence of 1.4% in nomads and 3.3% in industrial labourers.[23] Saberi et al. conducted a study on the personnel of a hospital in Kashan and reported the prevalence of 37% for constipation.[21] Honarkar et al. conducted a study in Bam, after the Bam earthquake. The prevalence of constipation in this city was 27.1%.[15] Moreover, in several studies, the criteria of Rome II was employed whilst some applied the Rome III criteria. None of the studies were nationwide and study populations only involved a proportion of the population of a city or province.

This systematic review showed the high prevalence of constipation in Iran. Few studies explored the risk factors of constipation. Scarce data are available regarding the natural history and quality of life in patients with constipation, and future effort should be focused on research on these subjects. Since, constipation is related to the decreased quality of life and also has major economic consequences, it is also highly suggested that further population-based studies be carried out in different provinces of Iran, to give an estimation of the prevalence of constipation and its related risk factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

This study was carried out by a grant from the Vice Chancellery for Research and Technology, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Walsh K, McWilliams SR, Maher MM, Quigley EM. The spectrum of functional gastrointestinal disorders in a tertiary referral clinic in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci. 2012;181(1):81–6. doi: 10.1007/s11845-011-0756-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):750–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peppas G, Alexiou VG, Mourtzoukou E, Falagas ME. Epidemiology of constipation in Europe and Oceania: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(11):3130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao YF, Ma XQ, Wang R, Yan XY, Li ZS, Zou DW, et al. Epidemiology of functional constipation and comparison with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome :the Systematic Investigation of Gastrointestinal Diseases in China (SILC) Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(8):1020–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jun DW, Park HY, Lee OY, Lee HL, Yoon BC, Choi HS, et al. A population-based study on bowel habits in a Korean community: prevalence of functional constipation and self-reported constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(8):1471–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wald A, Scarpignato C, Kamm MA, Mueller-Lissner S, Helfrich I, Schuijt C, et al. The burden of constipation on quality of life: results of a multinational survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(2):227–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarghi A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Habibi M, Haghdost AA, Solhpour A, Moazezi M, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and the influence of demographic factors. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102(S2):S426–S458. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pourhoseingholi A, Safaee A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Habibi M, Vahedi M, et al. Prevalence and demographic risk factors of gastrointestinal symptoms in Tehran province. JPH. 2010;7(1):42–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaboli SA, Pourhoseingholi MA, MoghimiDehkordi B, Safaee A, Habibi M, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Factors associated with functional constipation in Iranian adults: a population-based study. Gastroenterology and Hepatology From Bed to Bench. 2010;3(2):83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roshandel D, Rezailashkajani M, Shafaee S, Zali MR. Symptom patterns and relative distribution of functional bowel disorders in 1,023 gastroenterology patients in Iran. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21(8):814–25. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adibi P, Behzad E, Pirzadeh S, Mohseni M. Bowel habit reference values and abnormalities in young Iranian healthy adults. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(8):1810–3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoshbaten M, Hekmatdoost A, Ghasemi H, Entezariasl M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and signs in northwestern Tabriz, Iran. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23(5):168–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honarkar Z, Baladast M, Khorram Z, Akhondi Sh, Antikchi M, Masoodi M, et al. An analysis of gastrointestinal symptoms in causalities of catastrophic earthquake of Bam, Iran. Shiraz E-Medical Journal. 2005;6(1, 2) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohaghegh SH, Soori H, Khoshkrood MB, Vahedi M, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Pourhoseingholi MA, et al. Direct and indirect medical costs of functional constipation: a population-based study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(4):515–22. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Vahedi M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Khoshkrood MB, Safaee A, Habibi M, et al. Economic burden attributable to functional bowel disorders in Iran: a cross-sectional population-based study. J Dig Dis. 2011;12(5):384–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roshandel D, Rezailashkajani M, Shafaee S, Zali MR. A cost analysis of functional bowel disorders in Iran. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(7):791–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adibi P, Keshteli AH, Esmaillzadeh A, Afshar H, Roohafza H, Bagherian-Sararoudi H, et al. The study on the epidemiology of psychological, alimentary health and nutrition (SEPAHAN): overview of methodology. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(5) In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorouri M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Functional bowel disorders in Iranian population using Rome III criteria. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(3):154–60. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.65183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saberi HR, Moravveji AR. Gastrointestinal complaints in shift-working and day-working nurses in Iran. J Circadian Rhythms. 2010;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganji A, Malekzadeh F, Safavi M, NassriMoghaddam S, Nourie M, Merat Sh, et al. Digestive and liver disease statistics in Iran. Middle East Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2009;1(2):52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massarrat S, Saberi-Firoozi M, Soleimani A, Himmelmann GW, Hitzges M, Keshavarz H. Peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome and constipation in two populations in Iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7(5):427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di LC. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(1):3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien MD, Camilleri M, von der Ohe MR, Phillips SF, Pemberton JH, Prather CM, et al. Motility and tone of the left colon in constipation: a role in clinical practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(12):2532–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davudi K, Volkova LI. Structure of nutrition in Iranian population. Vopr Pitan. 2007;76(3):56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCrea GL, Miaskowski C, Stotts NA, Macera L, Varma MG. A review of the literature on gender and age differences in the prevalence and characteristics of constipation in North America. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):737–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Wijk CM, Kolk AM. Sex differences in physical symptoms: the contribution of symptom perception theory. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(2):231–46. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sloots CE, Felt-Bersma RJ, Meuwissen SG, Kuipers EJ. Influence of gender, parity, and caloric load on gastrorectal response in healthy subjects: a barostat study. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(3):516–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1022584632011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teff KL, Alavi A, Chen J, Pourdehnad M, Townsend RR. Muscarinic blockade inhibits gastric emptying of mixed-nutrient meal: effects of weight and gender. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(3 Pt 2):R707–R714. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.3.R707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wald A, Van Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, et al. Gastrointestinal transit: the effect of the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology. 1981;80(6):1497–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonenne J, Esfandyari T, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Stephens DA, Baxter KL, et al. Effect of female sex hormone supplementation and withdrawal on gastrointestinal and colonic transit in postmenopausal women. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(10):911–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tagart RE. The anal canal and rectum: their varying relationship and its effect on anal continence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1966;9(6):449–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02617443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walter S, Hallbook O, Gotthard R, Bergmark M, Sjodahl R. A population-based study on bowel habits in a Swedish community: prevalence of faecal incontinence and constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(8):911–6. doi: 10.1080/003655202760230865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delgado-Aros S, Locke GR, III, Camilleri M, Talley NJ, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Obesity is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal symptoms: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(9):1801–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sveinsdottir H. Self-assessed quality of sleep, occupational health, working environment, illness experience and job satisfaction of female nurses working different combination of shifts. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(2):229–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhen LW, Ann GK, Yu HK. Functional bowel disorders in rotating shift nurses may be related to sleep disturbances. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18(6):623–7. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]