Abstract

Chronic wounds represent a rising health and economic burden to our society. Emerging studies indicate that miRNAs play a key role in regulating several hubs that orchestrate the wound inflammation and angiogenesis processes. Of interest to wound inflammation are the regulatory loops where inflammatory mediators elicited following injury, are regulated by miRNAs as well as regulate miRNA expression. Adequate angiogenesis is a key determinant of success in ischemic wound repair. Hypoxia and cellular redox state are among the key factors that drive wound angiogenesis. We provided first evidence demonstrating that miRNAs regulate cellular redox environment via a NADPH oxidase dependent mechanism in human microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs). We further demonstrated that hypoxia-sensitive miR-200b is involved in induction of angiogenesis by directly targeting Ets-1 in HMECs. These studies points towards a potential role of miRNA in wound angiogenesis. miRNA-based therapeutics represents one of the major commercial hot spots in today’s biotechnology market space. Understanding the significance of miRs in wound inflammation and angiogenesis may help design therapeutic strategies for management of chronic non-healing wounds.

Keywords: miRNA, Inflammation, angiogenesis, oxidants, redox

1. miRNA in wound healing

Wound healing is a physiological response to injury that is conserved across tissue systems. Chronic wounds that fail to heal in an orderly manner represent a major health problem in the United States and costing in excess of US$25 billion annually1. For example, patients with a diabetic foot ulcer are seen by their outpatient health care provider about 14 times per year and are hospitalized about 1.5 times per year. The cost of care for these patients is estimated at $33,000 annually2. The discovery of miRs and their significance in biology represents a major breakthrough in molecular biology3–6. miR represent a key mechanism executing post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS)7. The human genome encodes 1,048 microRNAs (miRNAs). As per estimates, 30–50% of the human protein-coding genes are regulated by miRs8–12. Key elements of tissue repair such as stem cell biology, inflammation, hypoxia-response, and angiogenesis are all under the fine control of a network of wound-sensitive miRNAs13,14. Dysregulated response of the miR system to injury is likely to perturb the function of coding genes resulting in compromised wound healing. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a clear understanding of miR responses to wounding and their significance in specific aspects of healing.

Work in our laboratory has led to the maiden observation that cutaneous wound healing process involves changes in the expression of specific miRNA at various phases of healing 13–21. We recently provided evidence on the significance of O2-sensitive miRs in regulating cutaneous wound healing17. We also proposed the existence of regulatory loops where cytokines and other inflammatory mediators elicited following injury, are regulated by miRNAs which in turn regulate the expression of specific miRNA13,18. Adequate angiogenesis is a key determinant of success in ischemic wound repair. We demonstrated that miRNAs fine-tune the cellular redox state as well as hypoxia-induced angiogenesis, key drivers of cell signaling in wound angiogenesis16. In this review article, we summarize the relevant literature that unveils the potential significance of miRNAs in the regulation of wound inflammation and angiogenesis.

2. miRNA in wound inflammation

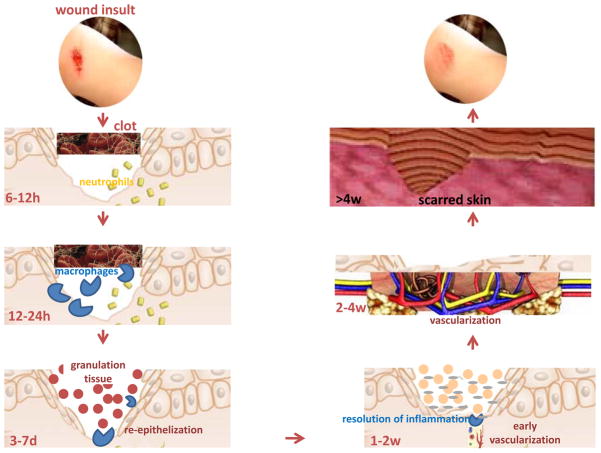

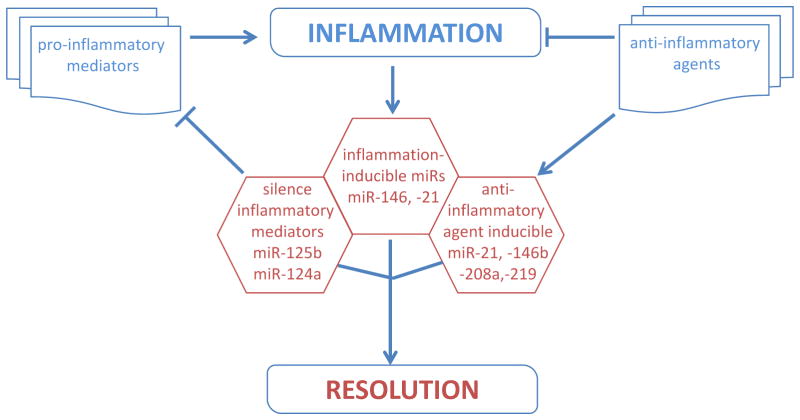

Wound-induced inflammatory response constitutes one of the earliest events that determine the fate and quality of healing (Figure 1)22. Cytokines, chemokines and growth factors produced by infiltrating immune cells during early inflammatory phase set the stage for tissue repair. The inflammatory response in wound is tightly regulated by signals that either i) initiate & maintain; or ii) resolve inflammation23. An imbalance between these signals may cause chronic inflammation derailing the healing cascade. Understanding the mechanisms that regulate the inflammatory response in wound repair will help design innovative strategies to address dysregulated inflammation as commonly noted in chronic ulcers. In the following section, we discuss evidences supporting that miRNAs regulate specific aspects of wound inflammation by targeting specific coding genes (Figure 2).

Fig. 1. Phases of cutaneous wound healing.

The process of wound healing for the ease of understanding is divided into specific functional phases, namely, hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. All these phases of healing take place in an overlapping series of programmed events to promptly reestablish barrier function of the skin.

Fig. 2. Potential role of miRNA in regulation of wound inflammation.

The inflammation response to wound is tightly regulated by signals that either i) initiate & maintain; or ii) resolve inflammation. An imbalance between these signals may cause chronic inflammation derailing the healing cascade. Of interest to wound inflammation are the regulatory loops where inflammatory mediators elicited following injury, are regulated by miRNAs as well as regulate miRNA expression.

2.1 MicroRNAs and inflammation related target genes

First, we discuss regulation of key cytokines and related factors by miRs (Table 1). TNF-α is known to be involved in tissue remodeling as well as mounting and sustenance of inflammation24. Depending on the concentration, length of exposure, and presence of other cytokines, the effect of TNFα can be beneficial or deleterious for tissue repair. Anti-TNF-α therapy directed towards attenuating TNF-α signaling in wounds restores diabetic wound healing25. Suppression of inflammation is desired in such setting where inflammation is excessive and long-term. On the other hand, inability to mount an appropriate inflammatory process after wounding hurts wound healing too. We have recently observed that agonists of TNFα production by wound macrophages can improve wound outcomes26. Post-transcriptional mechanisms impose a series of rate-limiting controls to modify the abundance of the TNF-α mRNA and the rate of its translation in response to inflammatory signals27. Such mechanisms consist of signaling networks converging on RNA-binding proteins as well as on miRNAs27. LPS-induced down-regulation of miR-125b is instrumental in bolstering the production of TNF-alpha28. miR-125b has been shown to bind to the 3′-UTR of TNF-α inhibiting the translation of this cytokine28. In addition, the genes regulated by TNFα i.e., E-selectin and ICAM-1 are direct targets of miR-31 and miR-17-3p, respectively 29.

Table 1.

miRNA regulation of major proteins involved with wound inflammation.

MCP-1

The CC chemokine macrophage chemoattractant protein (MCP-1/CCL2) is a major chemo-attractant for monocytes/macrophages. It also helps recruit a subset of T-cells and CCR3+ mast cells30. The expression of MCP-1 was highly upregulated (~70 fold) following wounding31. A putative consensus site for miR-124a binding in the 3′-UTR of MCP-1 mRNA has been identified. miR-124a specifically suppresses the reporter activity driven by the 3′-UTR of MCP-1 mRNA suggesting that miR-124a is directly implicated in the post-transcriptional silencing of MCP-132.

TLRs

Inflammatory cells, including macrophages and neutrophils, recognize invading microbial pathogens primarily through Toll-like receptors (TLRs)33. Depending on the adaptor molecules recruited to the TLR intracellular domain after ligand engagement, TLR-activated signaling events are largely defined as myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)-dependent or TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing IFN-β (TRIF)-dependent 34. MyD88-deficient mice exhibit severely impaired wound healing phenotype characterized by delayed granulation tissue formation and compromised blood vessel development independent of its role in host pathogen response35. miR-146a negatively regulates TLR signaling by targeting TRAF6 and IRAK-1, IRAK236. The microRNA-146 family (miR-146a/b) regulates TLR4 through a negative feedback loop mechanism37. IRAK1 and TRAF6 represent two prominent targets of miR-146a that enable negatively regulation of the release of IL-8 and RANTES 38. In addition to TRAF6 and IRAK-1, IRAK2 has been identified as another target of miR-146a which regulates IFNγ production39.

Lipid mediators

Lipid mediators such as eicosanoids consist of a family of biologically active metabolites, including prostaglandins (PG), prostacyclin (PC), thromboxanes (TX), leukotrienes (LT), and lipoxins (LX)40. Free arachidonic acid is metabolized through the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway, involving COX-1 and COX-2, along with terminal synthases, to generate PG, PC and TX. Eicosanoids are well known to initiate, amplify, and perpetuate inflammation in both acute as well as chronic wounds41. The ω-3 poly unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), eicosapentaenoic (EPA; i.e., ω-3, C20:5) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; i.e., ω-3, C22:6) are transformed, in a manner equivalent to arachidonic acid metabolism, by COX-2 and lipoxygenase (LOX) enzymes to generate novel classes of endogenous lipid autacoids with anti-inflammatory and protective function40. Induction of COX-2 represents one of the earliest responses following cutaneous injury42. miR-101a and miR-199a have been implicated in the inhibiting COX-2 expression in the murine uterus during embryo implantation43.

2.2 Resolution of inflammation

Cues and mechanisms that govern the resolution of inflammation play a key role in wound healing 23. TGFβ1 and IL-10 represent major anti-inflammatory factors that direct the inflammation response following injury towards a successful resolution23. As a physiological response to wounding, TGF-β1 is released in large amounts from platelets. TGFβ1 serves as a chemo-attractant for neutrophils, macrophages, and fibroblasts30. Signaling via active TGFβ involves recruitment of SMAD proteins44. SMAD proteins are now known to play a regulatory role in the processing of miRNA (miR biogenesis) into the nucleus45. Receptor-activated SMADs induce processing of a subset of miRNAs, particularly miR-2146. Furthermore, miR-128a targets TGFβR1 protein expression by binding to the 3′UTR region of this gene 47. IL-10 is another major suppressor of the inflammatory response. It does so by down-regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory genes such as TNFα 48. Current evidence show that insufficiency of IL-10 is a key factor underlying the exaggerated and sustained inflammatory response commonly noted in diabetic wounds49. In macrophages stimulated with TLR ligand, miR-466l can upregulate both mRNA and protein expression of IL-10 via competitive binding to the 3′ UTR that contains contain AU-rich elements (ARE). The RNA-binding protein tristetraprolin (TTP) mediates rapid degradation of IL-10 mRNA via binding to the ARE. Thus, binding of miR-466l to IL-10 ARE prevents TTP mediated IL-10 mRNA degradation extending the half-life of IL-10 mRNA50.

Lipid mediators, including lipoxins, resolvins, protectin, and maresins, have been identified as key factors that are implicated in resolution of inflammation response51. These mediators are endogenously synthesized from essential fatty acids such as arachidonic acid during acute inflammation51. Recently, the anti-inflammatory lipid mediator Resolvin D1 has been shown to modify the expression of miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-146b, miR-208a, and miR-219 52.

2.3 Expression and regulation of microRNAs in immune cells

miR-21, miR-155, miR-424, and miR-17-92, and their transcriptional regulatory control are directly implicated in monocytic differentiation53. The relative levels of PU.1 and C/EBPα determine cell fate between monocyte and granulocyte as end-products54,55. PU.1 activates the transcription of miR-424 stimulating monocyte differentiation through miR-424-dependent translational repression of the transcription factor NFIA. Ectopic expression of miR-424 in precursor cells enhances monocytic differentiation underscoring the significance of miR-424 in controlling the monocyte/macrophage differentiation program56. miR-223, preferentially expressed in myeloid cells57, also plays an essential role in modulating the myeloid differentiation response58. Over-expression of miR-223 significantly increased the number of cells committed to the granulocyte-specific lineage in a granulocyte differentiation model. The loss of function study shows that miR-223 had the opposite effects on the differentiation process58. Furthermore, miR-223 is involved in an auto-regulatory feedback loop to control its own expression and enhance granulocytic differentiation57. These evidences underscore the significance of miRNA in myeloid cell differentiation into active macrophages, a key driver of wound inflammation.

2.2 miRNA regulated by the inflammatory response

miR-146, miR-155 and miR-21 have been of particular interest for research associated with inflammatory and immune responses. These miRNAs are induced by pro-inflammatory stimuli such as IL-1β, TNFα and TLRs 59. The miR-146 family is composed of two members, miR-146a and miR-146b38. Promoter analysis studies recognized miR-146a as a NF-κB dependent gene36. Exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα or IL-1β, or the ligands of TLR-2, -4 or -5 ligands (e.g., bacterial and fungal components) potently induce miR-146 expression in myeloid cells28,36,60. The ligands of TLR -3, -7 or -9 (e.g., single or double stranded RNA and CpG motifs) fail to induce miR-14638. miR-155 represents a common target of a broad range of inflammatory mediators including TNFα, LPS, polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic (PI:PC) acid and IFNβ 60. miR-155 is encoded within an exon of the non-coding RNA known as bic (B-cell integration cluster). Bic null mice studies recognized miR-155 as a central regulator of lymphocyte differentiation61. Of note, IL-10 inhibits the LPS-inducible expression of miR-155 62 while miR-21 or miR-146a remain unaffected. IL-10 inhibits the transcription of miR-155 from the BIC gene in a STAT3-dependent manner thus allowing SHIP1 expression to recover and promote the conversion of PIP3 back to its inactive PIP2 state, switching off the pro-inflammatory response62. miR-21, initially described as “oncomir”, is known to be a common inflammation-inducible miR. The putative miR-21 promoter region contains three AP1 and one PU.1 binding sites63. Computational analyses predicted transcription repressor NFIB mRNA as a target for miR-21 and the miR-21 promoter itself contains a conserved binding site for the NFIB protein63,64. In silico analyses combined with experimental biology approaches have identified numerous target proteins whose expression is regulated by miR-21. PTEN represents major target of miR-2165. Using laser-capture microdissection technique we demonstrated that miR-21 signal was localized to cardiac fibroblasts of the infarcted region of the ischemia-reperfused heart. PTEN was identified as a direct target of miR-21 in cardiac fibroblasts66. Another target of miR-21 is pro-inflammatory PDCD4. A deceased level of PDDC4 is known to drive IL-10 production in response to LPS67.

Inflammatory response such as TLR4 activation induces the expression of miR-125b expression. miR-125b, in turn, directly targets and silences TNFα. This exemplifies a regulatory loop where inflammatory response induces a specific miRNA which in turn silences pro-inflammatory signals28.

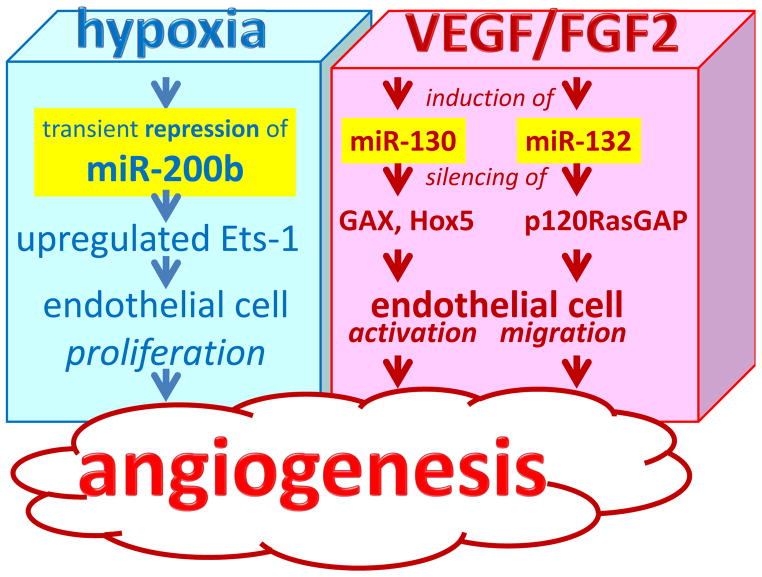

3.0 miRNA in Wound Angiogenesis

Wound vascularization is controlled by all phases of wound healing – hemostasis, inflammation, tissue formation as well as tissue remodeling (Figure 1). Early stages of wound vascularization include endothelial cell proliferation and migration followed by capillary formation where the sprouting of capillaries into the wound bed is critical to support the regenerating tissue. Initial observations establishing the significance of miRs in guiding vascularization came from experimental studies involved in arresting miRNA biogenesis by Dicer knockdown in vascular cells and tissues to deplete available mature miR pools 16,68–71. Dicer represents a key enzyme involved in miRNA biogenesis72. A key significance of miRNAs in the regulation of mammalian vascular biology was established from studies involved in blocking miRNA biogenesis to deplete the miRNA pools of vascular tissues and cell 68,69,73. The dicer gene is significantly expressed throughout the embryonic tissues as early as day 11 and remains constant through day 1773. Starting from embryonic day 11.5, virtually all homozygous dicerex1/2 (lacking the first two exons of dicer homozygous mutant mice) embryos were growth and developmentally retarded as compared with their wild type or heterozygous litter mates. The embryos that were still viable at this stage however, had thin and sub-optimally developed blood vessels providing evidence that miR are required for blood vessel development during embryogenesis 73. Profound dysregulation of angiogenesis-related genes in vitro and in vivo was noticed after Dicer knock down74,75. Several aspects of angiogenesis, such as proliferation, migration, and morphogenesis of endothelial cell are modified by specific miRNAs in an endothelial-specific manner (Figure 3)13. Endothelial miRs involved in angiogenesis, also referred to as angiomirs, include miR 17-5p, cluster 17–92, miR-15b, -16, -20, -21, -23a, -23b, -24, -27a, -29a,-30a, -30c, -31, -100, -103, -106, 125a and -b, -126, -181a, -191, -199a, -221, -222, -320, and let-7 family76. Angiomirs represent therapeutic targets which may be manipulated to improved tissue vascularization outcomes.

Fig. 3. microRNAs in wound angiogenesis.

Angiogenesis is a result of a cascade of events which begins with the production and release of angiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and FGF-2. Hypoxia also controls angiogenesis. Several aspects of angiogenesis, such as proliferation, migration, and morphogenesis of endothelial cell are modified by specific miRNAs. Endothelial miRs involved in angiogenesis are referred to as angiomirs.

3.1 miRNA control of redox and NADPH oxidase

Oxidants generated during in inflammation may play a central role in supporting tissue vascularization77. Decomposition of endogenous H2O2 at the wound site by adenoviral catalase gene transfer impaired wound tissue vascularization78. Consistently, impairment in healing responses was noted in both NADPH oxidase deficient mice as well as humans78,79. These and related studies point towards a central role of NADPH oxidase derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) as signaling messengers in driving wound angiogenesis80,81. We examined whether redox control of angiogenesis is subject to regulation by miRNA. A Dicer knockdown approach was used to test the significance of miRNA in controlling redox state and angiogenic response of human microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs). Dicer knockdown resulted in lowering of mature miRNA pool and diminished the angiogenic response of HMECs as determined by cell migration and Matrigel tube formation. Such impairment of angiogenic response in the Matrigel was rescued by exogenous low micromolar H2O2. Dicer knockdown in HMECs showed lower inducible production of ROS when activated with phorbol ester, TNFα, or VEGF. Limiting the production of ROS by antioxidant treatment or NADPH oxidase knockdown approaches impaired angiogenic responses. Lowered inducible ROS production following Dicer knockdown was associated with lower expression of p47phox protein in these cells. We identified that lowering of miRNA content by dicer knockdown resulted in the induced expression of the transcription factor HBP1, a suppressor transcription factor that negatively regulates p47phox expression. Knockdown of HBP1 restored the angiogenic response of miRNA-deficient HMECs 15,16. This study provided the first evidence that cellular redox state, a key driver of cell signaling, is controlled by miRNAs. Results of this study lead to the hypothesis that miRNA may modify wound angiogenesis and therefore influence wound healing outcomes.

3.2 Hypoxia-regulated miR expression in angiogenesis

The injured tissue often suffers from disrupted vasculature leading to insufficient oxygen supply or hypoxia. Hypoxia is widely recognized as a cue that drives angiogenesis as part of an adaptive response to vascularize the oxygen-deficient host tissue. We noted hypoxia-repressible miR-200b is involved induction of angiogenesis via directly targeting v-ets Erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1 (Ets-1)20. We reported that both hypoxia as well as HIF-1α stabilization inhibited miR-200b expression. In HMEC cells, miR-200b-knockdown using miR-200b inhibitors exhibited elevated angiogenesis as evidenced by Matrigel® tube formation and increased cell migration. Conversely, delivery of the miR-200b mimic in HMECs inhibited the angiogenic response. ETS-1, a crucial angiogenesis-related transcription factor, served as a novel direct target of miR-200b. Certain Ets-1-associated genes, namely matrix metalloproteinase 1 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, were silenced by miR-200b. Overexpression of Ets-1 rescued miR-200b-dependent impairment in angiogenic response and suppression of Ets-1-associated gene expression20. Taken together, the results demonstrate that transient down-regulation of miR-200b helps jump-start wound angiogenesis.

3.3 Proangiogenic stimuli

VEFG and FGF-2 represent two key stimuli that drive wound angiogenesis in a concerted manner. Immediately after injury, FGF-2 is released early, providing an early stimulus for endothelial cell proliferation. VEGF is produced as the FGF-2 levels decline. VEGF provides a more sustained stimulus for endothelial cell migration and differentiation into new capillary tubes82. VEGF-A has been shown to induce, in a time-dependent manner, the expression of miR-191, -155, -31, -17-5p, -18a, and miR-20a in HUVEC69. Both VEGF-A, and basic FGF-2 increased the expression of miR-130a, a pro-angiogenic miRNA, which directly targets GAX and HOXA583. VEGF-A and bFGF signaling phosphorylate CREB causing rapid transcription of miR-13284. miR-132 overexpression increased endothelial cell proliferation and in vitro networking by targeting p120RasGAP, a GTPase-activating protein84. miR-221 and miR-222 have been identified as modifying c-Kit expression as well as the angiogenic properties of the c-kit ligand Stem Cell Factor. The miR-221/2 and c-Kit interaction represents an integral component of a complex circuit that controls the ability of endothelial cells to form new capillaries 85. Inhibition of c-kit results in reduced VEGF expression86.

4.0 miRNA-based Therapeutics

The role of miRNAs in a complex biological event such as inflammation and angiogenesis during wound healing is unfolding and remains to be fully understood. miRs lends themselves to clinical therapeutics87,88 and are of extraordinary translational value13. Exploiting miRNAs for therapeutic purposes has great potential for two principal reasons: i) a single miRNA can regulate multiple functionally-convergent target genes thus acting as an amplifier, and ii) miRNAs are relatively stable small molecules the tissue levels of which can be successfully manipulated by a growing number of technologies. Broadly, two major options are available: over-expression or silencing of the select miRNA. For the former, delivery of corrective synthetic miRNA in the form of (siRNA-like) dsRNA may be productive. For a disease phenotype caused by abnormal miRNA-dependent inhibition of a specific subset of mRNA, oligonucleotides complementary to either the mature miRNA or its precursors can be designed such that the miRNA will be functionally arrested and will not be able to bind the target mRNA subset. Successful design of such oligonucleotide should include considerations such as successful in vivo delivery, resistance to degradation in tissues, and specificity/highbinding affinity to the specific miRNA in question. This can be achieved by chemical modification of the nucleotides, especially the addition of chemical groups to the 2′-hydroxyl group89. The delivery of antagonists or mimics using viral and non-viral methods for gene therapy is of current interest and significant advances have been achieved through nanotechnology. Several companies are now developing miRNA-based therapeutics. Santaris Pharmaceuticals has launched a phase I clinical trial for the treatment of hepatitis C. The focus is on liver-specific miRNA-122, which is involved in hepatitis C replication and cholesterol metabolism. Regulus Therapeutics is developing therapies based on miR-122 inhibition to treat hepatitis C infection71. Regulus Therapeutics is also targeting miR-155 with anti-miRs to treat inflammatory diseases. miRNA-based therapies are lucrative as they provide fine tools enabling precise and temporally controlled manipulation of cell-specific miRNAs. Treatment of skin wounds has lower barriers because it lends itself to local delivery of miRNA mimics and antagonizing agents13.

Acknowledgments

Wound healing research in the authors’ laboratory is funded by DK076566 (SR) and GM069589, GM 077185 and NS42617 (CKS).

Biographies

Sashwati Roy, PhD is an Associate Professor of Surgery at the Ohio State University Columbus Ohio. Her research interest include wound inflammation, mechanisms of resolution of diabetic wound inflammation, role of miRNA in tissue repair processes.

Chandan Sen, PhD is a Professor of Surgery at the Ohio State University (OSU). He serves as the Director for Comprehensive Wound Center at OSU. This center has over 1500 patient visits every month and is nationally known for its excellence in wound healing research. Dr. Sen’s research interest include role of oxygen, redox and miRNA in tissue repair and regeneration.

References

- 1.Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Human skin wounds: A major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margolis DJ, Malay DS, Hoffstad OJ, Leonard CE, MaCurdy T, Tan Y, Molina T, de Nava KL, Siegel KL. Economic burden of diabetic foot ulcers and amputations: Data points #3. 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobert O. Gene regulation by transcription factors and micrornas. Science. 2008;319:1785–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1151651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Check E. Rna interference: Hitting the on switch. Nature. 2007;448:855–858. doi: 10.1038/448855a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartel DP. Micrornas: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pressman S, Bei Y, Carthew R. Posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2007;130:570. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microrna targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. Rnahybrid: Microrna target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W451–454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sassen S, Miska EA, Caldas C. Microrna: Implications for cancer. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0532-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smalheiser NR, Torvik VI. Complications in mammalian microrna target prediction. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;342:115–127. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-123-1:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu W, Sun M, Zou GM, Chen J. Microrna and cancer: Current status and prospective. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:953–960. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen CK. Micrornas as new maestro conducting the expanding symphony orchestra of regenerative and reparative medicine. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:517–520. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00037.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sen CK, Roy S. Microrna in cutaneous wound healing. In: Ying S-Y, editor. Current perspectives in micrornas. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shilo S, Roy S, Khanna S, Sen CK. Microrna in cutaneous wound healing: A new paradigm. DNA Cell Biol. 2007;26:227–237. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shilo S, Roy S, Khanna S, Sen CK. Evidence for the involvement of mirna in redox regulated angiogenic response of human microvascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:471–477. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswas S, Roy S, Banerjee J, Hussain SR, Khanna S, Meenakshisundaram G, Kuppusamy P, Friedman A, Sen CK. Hypoxia inducible microrna 210 attenuates keratinocyte proliferation and impairs closure in a murine model of ischemic wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6976–6981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001653107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy S, Sen CK. Mirna in innate immune responses: Novel players in wound inflammation. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:557–565. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00160.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sen CK, Gordillo G, Khanna S, Roy S. Micromanaging vascular biology: Tiny micrornas play big band. J Vasc Res. 2009 doi: 10.1159/000226221. invited review - in revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan YC, Khanna S, Roy S, Sen CK. Mir-200b targets ets-1 and is down-regulated by hypoxia to induce angiogenic response of endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2047–2056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.158790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee J, Chan YC, Sen CK. Micrornas in skin and wound healing. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:543–556. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00157.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eming SA, Krieg T, Davidson JM. Inflammation in wound repair: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:514–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy S. Resolution of inflammation in wound healing: Significance of dead cell clearance. In: Sen CK, editor. Wound healing society year book. New Rochelle, NY: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers; 2010. pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sander AL, Henrich D, Muth CM, Marzi I, Barker JH, Frank JM. In vivo effect of hyperbaric oxygen on wound angiogenesis and epithelialization. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goren I, Muller E, Schiefelbein D, Christen U, Pfeilschifter J, Muhl H, Frank S. Systemic anti-tnfalpha treatment restores diabetes-impaired skin repair in ob/ob mice by inactivation of macrophages. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2007;127:2259–2267. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy S, Dickerson R, Khanna S, Collard E, Gnyawali U, Gordillo GM, Sen CK. Particulate beta-glucan induces tnf-alpha production in wound macrophages via a redox-sensitive nf-kappabeta-dependent pathway. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19:411–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stamou P, Kontoyiannis DL. Posttranscriptional regulation of tnf mrna: A paradigm of signal-dependent mrna utilization and its relevance to pathology. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2010;11:61–79. doi: 10.1159/000289197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, Costinean S, Dumitru CD, Adair B, Fabbri M, Alder H, Liu CG, Calin GA, Croce CM. Modulation of mir-155 and mir-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/tnf-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 2007;179:5082–5089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suarez Y, Wang C, Manes TD, Pober JS. Cutting edge: Tnf-induced micrornas regulate tnf-induced expression of e-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on human endothelial cells: Feedback control of inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:21–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:835–870. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy S, Khanna S, Rink C, Biswas S, Sen CK. Characterization of the acute temporal changes in excisional murine cutaneous wound inflammation by screening of the wound-edge transcriptome. Physiol Genomics. 2008;34:162–184. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00045.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamachi Y, Kawano S, Takenokuchi M, Nishimura K, Sakai Y, Chin T, Saura R, Kurosaka M, Kumagai S. Microrna-124a is a key regulator of proliferation and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 secretion in fibroblast-like synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1294–1304. doi: 10.1002/art.24475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Neill LA. How toll-like receptors signal: What we know and what we don’t know. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macedo L, Pinhal-Enfield G, Alshits V, Elson G, Cronstein BN, Leibovich SJ. Wound healing is impaired in myd88-deficient mice: A role for myd88 in the regulation of wound healing by adenosine a2a receptors. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1774–1788. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. Nf-kappab-dependent induction of microrna mir-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lederhuber H, Baer K, Altiok I, Sadeghi K, Herkner KR, Kasper DC. Microrna-146: Tiny player in neonatal innate immunity? Neonatology. 2010;99:51–56. doi: 10.1159/000301938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams AE, Perry MM, Moschos SA, Larner-Svensson HM, Lindsay MA. Role of mirna-146a in the regulation of the innate immune response and cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:1211–1215. doi: 10.1042/BST0361211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou J, Wang P, Lin L, Liu X, Ma F, An H, Wang Z, Cao X. Microrna-146a feedback inhibits rig-i-dependent type i ifn production in macrophages by targeting traf6, irak1, and irak2. J Immunol. 2009;183:2150–2158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gronert K. Lipid autacoids in inflammation and injury responses: A matter of privilege. Mol Interv. 2008;8:28–35. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broughton G, 2nd, Janis JE, Attinger CE. The basic science of wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:12S–34S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000225430.42531.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberyszyn TM. Inflammation and wound healing. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2993–2999. doi: 10.2741/2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chakrabarty A, Tranguch S, Daikoku T, Jensen K, Furneaux H, Dey SK. Microrna regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 during embryo implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15144–15149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705917104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakefield LM, Roberts AB. Tgf-beta signaling: Positive and negative effects on tumorigenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:22–29. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hata A, Davis BN. Control of microrna biogenesis by tgfbeta signaling pathway-a novel role of smads in the nucleus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:517–521. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu G, Friggeri A, Yang Y, Milosevic J, Ding Q, Thannickal VJ, Kaminski N, Abraham E. Mir-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1589–1597. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masri S, Liu Z, Phung S, Wang E, Yuan YC, Chen S. The role of microrna-128a in regulating tgfbeta signaling in letrozole-resistant breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0716-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annual Review of Immunology. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khanna S, Biswas S, Shang Y, Collard E, Azad A, Kauh C, Bhasker V, Gordillo GM, Sen CK, Roy S. Macrophage dysfunction impairs resolution of inflammation in the wounds of diabetic mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma F, Liu X, Li D, Wang P, Li N, Lu L, Cao X. Microrna-466l upregulates il-10 expression in tlr-triggered macrophages by antagonizing rna-binding protein tristetraprolin-mediated il-10 mrna degradation. J Immunol. 2010;184:6053–6059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serhan CN. Maresins: Novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J Exp Med. 2009;206:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Recchiuti A, Krishnamoorthy S, Fredman G, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Micrornas in resolution of acute inflammation: Identification of novel resolvin d1-mirna circuits. FASEB J. 2011;25:544–560. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-169599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmeier S, MacPherson CR, Essack M, Kaur M, Schaefer U, Suzuki H, Hayashizaki Y, Bajic VB. Deciphering the transcriptional circuitry of microrna genes expressed during human monocytic differentiation. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott EW, Simon MC, Anastasi J, Singh H. Requirement of transcription factor pu.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science. 1994;265:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.8079170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Radomska HS, Huettner CS, Zhang P, Cheng T, Scadden DT, Tenen DG. Ccaat/enhancer binding protein alpha is a regulatory switch sufficient for induction of granulocytic development from bipotential myeloid progenitors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4301–4314. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosa A, Ballarino M, Sorrentino A, Sthandier O, De Angelis FG, Marchioni M, Masella B, Guarini A, Fatica A, Peschle C, Bozzoni I. The interplay between the master transcription factor pu.1 and mir-424 regulates human monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19849–19854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706963104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sonkoly E, Stahle M, Pivarcsi A. Micrornas and immunity: Novel players in the regulation of normal immune function and inflammation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fazi F, Rosa A, Fatica A, Gelmetti V, De Marchis ML, Nervi C, Bozzoni I. A minicircuitry comprised of microrna-223 and transcription factors nfi-a and c/ebpalpha regulates human granulopoiesis. Cell. 2005;123:819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheedy FJ, O’Neill LA. Adding fuel to fire: Micrornas as a new class of mediators of inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(Suppl 3):iii50–55. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. Microrna-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turner M, Vigorito E. Regulation of b- and t-cell differentiation by a single microrna. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:531–533. doi: 10.1042/BST0360531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCoy CE, Sheedy FJ, Qualls JE, Doyle SL, Quinn SR, Murray PJ, O’Neill LA. Il-10 inhibits mir-155 induction by toll-like receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20492–20498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fujita S, Ito T, Mizutani T, Minoguchi S, Yamamichi N, Sakurai K, Iba H. Mir-21 gene expression triggered by ap-1 is sustained through a double-negative feedback mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jazbutyte V, Thum T. Microrna-21: From cancer to cardiovascular disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:926–935. doi: 10.2174/138945010791591403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meng F, Henson R, Lang M, Wehbe H, Maheshwari S, Mendell JT, Jiang J, Schmittgen TD, Patel T. Involvement of human micro-rna in growth and response to chemotherapy in human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2113–2129. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roy S, Khanna S, Hussain SR, Biswas S, Azad A, Rink C, Gnyawali S, Shilo S, Nuovo GJ, Sen CK. Microrna expression in response to murine myocardial infarction: Mir-21 regulates fibroblast metalloprotease-2 via phosphatase and tensin homologue. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:21–29. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheedy FJ, Palsson-McDermott E, Hennessy EJ, Martin C, O’Leary JJ, Ruan Q, Johnson DS, Chen Y, O’Neill LA. Negative regulation of tlr4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor pdcd4 by the microrna mir-21. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:141–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of dicer and drosha for endothelial microrna expression and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:59–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C, Yu J, Gerber SA, Harrison KD, Pober JS, Iruela-Arispe ML, Merkenschlager M, Sessa WC. Dicer-dependent endothelial micrornas are necessary for postnatal angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14082–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804597105. Epub 12008 Sep 14088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang Z, Wu J. Micrornas and regenerative medicine. DNA Cell Biol. 2007;26:257–264. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seto AG. The road toward microrna therapeutics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1298–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jaskiewicz L, Filipowicz W. Role of dicer in posttranscriptional rna silencing. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;320:77–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75157-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang WJ, Yang DD, Na S, Sandusky GE, Zhang Q, Zhao G. Dicer is required for embryonic angiogenesis during mouse development. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9330–9335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Targeting microrna expression to regulate angiogenesis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C, Pober JS, Sessa WC. Dicer dependent micrornas regulate gene expression and functions in human endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:1164–1173. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265065.26744.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Caporali A, Emanueli C. Microrna regulation in angiogenesis. Vascul Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arbiser JL, Petros J, Klafter R, Govindajaran B, McLaughlin ER, Brown LF, Cohen C, Moses M, Kilroy S, Arnold RS, Lambeth JD. Reactive oxygen generated by nox1 triggers the angiogenic switch. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022630199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roy S, Khanna S, Nallu K, Hunt TK, Sen CK. Dermal wound healing is subject to redox control. Mol Ther. 2006;13:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sen CK. The general case for redox control of wound repair. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2003;11:431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sen CK, Khanna S, Gordillo G, Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Roy S. Oxygen, oxidants, and antioxidants in wound healing: An emerging paradigm. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;957:239–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sen CK, Khanna S, Babior BM, Hunt TK, Ellison EC, Roy S. Oxidant-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human keratinocytes and cutaneous wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33284–33290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nissen NN, Polverini PJ, Koch AE, Volin MV, Gamelli RL, DiPietro LA. Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates angiogenic activity during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1445–1452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen Y, Gorski DH. Regulation of angiogenesis through a microrna (mir-130a) that down-regulates antiangiogenic homeobox genes gax and hoxa5. Blood. 2008;111:1217–1226. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anand S, Majeti BK, Acevedo LM, Murphy EA, Mukthavaram R, Scheppke L, Huang M, Shields DJ, Lindquist JN, Lapinski PE, King PD, Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Microrna-132-mediated loss of p120rasgap activates the endothelium to facilitate pathological angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2010;16:909–914. doi: 10.1038/nm.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Poliseno L, Tuccoli A, Mariani L, Evangelista M, Citti L, Woods K, Mercatanti A, Hammond S, Rainaldi G. Micrornas modulate the angiogenic properties of huvec. Blood. 2006 doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-012369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Litz J, Krystal GW. Imatinib inhibits c-kit-induced hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha activity and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1415–1422. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garofalo M, Croce CM. Micrornas: Master regulators as potential therapeutics in cancer. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:25–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Broderick JA, Zamore PD. Microrna therapeutics. Gene Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weiler J, Hunziker J, Hall J. Anti-mirna oligonucleotides (amos): Ammunition to target mirnas implicated in human disease? Gene Ther. 2006;13:496–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]