Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to rate the importance of primary healthcare (PHC) attributes in evaluations of PHC organizational models in Canada.

Methods:

Using the Delphi process, we conducted a consensus consultation with 20 persons recognized by peers as Canadian PHC experts, who rated the importance of PHC attributes within professional and community-oriented models of PHC.

Results:

Attributes rated as essential to all models were designated core attributes: first-contact accessibility, comprehensiveness of services, relational continuity, coordination (management) continuity, interpersonal communication, technical quality of clinical care and clinical information management. Overall, while all were important, non-core attributes – except efficiency/productivity – were rated as more important in community-oriented than in professional models. Attributes rated as essential for community-oriented models were equity, client/community participation, population orientation, cultural sensitivity and multidisciplinary teams.

Conclusion:

Evaluation tools should address core attributes and be customized in accordance with the specific organizational models being evaluated to guide health reforms.

Abstract

Objet :

L'objectif de cette étude était de classer selon leur importance différentes caractéristiques liées à l'évaluation des modèles organisationnels de soins de santé primaires (SSP) au Canada.

Méthode :

Au moyen du procédé Delphi, nous avons mené une consultation de consensus auprès de 20 personnes reconnues par leurs pairs comme des experts canadiens des SSP. Ils ont classé selon leur importance des caractéristiques des SSP au sein des modèles de SSP professionnels et axés sur la communauté.

Résultats :

Les caractéristiques classées comme essentielles pour tous les modèles ont été désignées comme caractéristiques centrales : accessibilité de premier contact, intégralité des services, continuité relationnelle, continuité d'approche (gestion), communication interpersonnelle, qualité technique des soins cliniques et gestion de l'information clinique. En général, bien qu'elles soient toutes importantes, les caractéristiques non centrales (à l'exception de l'efficience et de la productivité) ont été classées plus importantes pour les modèles axés sur la communauté que pour les modèles professionnels. Les caractéristiques classées essentielles pour les modèles axés sur la communauté sont : l'équité, la participation des clients et de la communauté, l'approche axée sur la population, la sensibilité aux aspects culturels et les équipes multidisciplinaires.

Conclusion :

Les outils d'évaluation devraient tenir compte des caractéristiques centrales et être adaptés en fonction des modèles organisationnels évalués, afin d'orienter les réformes de la santé.

Primary healthcare (PHC) has recently received substantial attention in many industrialized countries. In Canada, national and provincial commissions have identified problems in how PHC is organized (Romanow 2002; Kirby and LeBreton 2002; Clair 2000; Government of Ontario 2000; Government of Saskatchewan 2001; Government of Alberta 2001), and have suggested reform of the PHC system as a means of solving problems affecting the healthcare system as a whole. In particular, the accessibility and comprehensiveness of PHC services should be strengthened to better fulfill their mandate and maximize their contribution to the health of Canadians.

Most Canadian provinces have undertaken PHC reforms. Although most efforts focus on encouraging physicians and other health professionals to work collaboratively, in various jurisdictions reforms have involved specific organizational innovations in PHC models. It is thus crucial to develop frameworks and tools for ongoing evaluation of reforms that take into account the heterogeneity of organizational forms present in the health system.

This paper is part of a series of studies aimed at providing such a framework and tools, one of which was a consultation with Canadian PHC experts to establish operational (i.e., measurable) definitions of the attributes that should be evaluated in current and proposed models in Canada (Haggerty et al. 2007). In addition, experts rated the importance of different attributes within different models of PHC. In this paper, we report the results of this process.

We use “primary healthcare” to refer minimally both to services serving as first contact with the healthcare system and comprehensively to the place where a broad range of health-related needs are managed. We consider PHC organizational models to be those that provide at least general medical services by family physicians or generalists, who may or may not work with other health and social service professionals. Furthermore, we use a taxonomy (Lamarche et al. 2003) to classify PHC models as two archetypes, either professional or community-oriented. These two classes emerge based on an analysis of the vision, resources, governance structures and practices of PHC models worldwide, and they correspond roughly to what are often identified as “primary care” and “primary health care,” respectively.

Professional models are generally managed autonomously by family physicians, funded as small businesses through physician compensation. They provide general medical services, and their aim is to respond to medical needs of patients who present to, or have registered with, the PHC provider. This is the predominant model in Canada, but it encompasses a variety of sub-models such as single-physician practices, walk-in clinics and family medicine group practices. Recent reforms have seen a move towards the integration of primary care nurses and other disciplines and towards physician remuneration methods other than fee-for-service. Examples are family health teams (FHTs, Ontario), primary care networks (PCNs, Alberta) and primary health care organizations (PHCOs, British Columbia).

Community-oriented PHC models aim at improving the health of populations and are organized to meet health needs in the broader sense than just medical care. They are generally managed by public or community administrations and usually include a wide range of professionals who deliver a broad spectrum of health and social services. This model is less prevalent in Canada, although there is a long history with local community service centres (CLSCs) in Quebec and community health centres (CHCs) in Ontario and Saskatchewan. Recent reforms saw the establishment of similar models in New Brunswick and British Columbia.

Methods

We used the Delphi method for consensus-building. In this iterative process, documents pass through a series of revisions by a small group of experts, whose feedback each time is incorporated into successive rounds until consensus is achieved. This method has been described elsewhere (Haggerty et al. 2007) and is summarized here.

We used a snowball sampling technique to identify Canadian PHC experts. These were persons identified by at least two persons as having accumulated significant knowledge about PHC through clinical, managerial or academic activities. We identified 26 such experts, equally balanced among clinicians, academics and decision-makers from all regions in the country, of whom 20 were successfully contacted and 18 participated in at least two rounds. We conducted four rounds between June and October 2004, averaging 13 participants each.

In addition to identifying attributes and proposing operational definitions for them, the experts were asked to rank each attribute's importance for the two archetypes of PHC models. In the first round, they were asked to score the importance of attributes as (1) essential to core functions of PHC, (2) important but not essential or (3) relevant only to some forms of PHC organization. Attributes unanimously scored as 1 were designated core attributes and were no longer submitted to discussion.

In subsequent rounds, we asked experts to rank the importance of remaining attributes, this time within professional models and community-oriented PHC models. They were asked to score the importance of attributes for each model type as (1) essential to its core function, (2) important but not essential to its core function or (3) not relevant to this model. Again, attributes unanimously scored as 1 were considered core attributes for that model.

Based on the importance of the scores of the fourth round, we calculated the means and standard deviations of the scores. These were used to rank attributes within organizational models. In this way, we identified attributes that were essential (scores of 1.0–1.1), essential–important (1.2–1.3), very important (1.4–1.8), important (1.9) and somewhat important (2.0+).

Results

The Delphi process identified and defined 24 attributes of primary care (Haggerty et al. 2007). In the first round, seven attributes were scored unanimously as essential to core function and were thus identified as core attributes for all types of primary care organization. These are: first-contact accessibility; comprehensiveness of services; relational continuity; coordination (management) continuity; interpersonal communication; technical quality of clinical care; and clinical information management. Table 1 presents the 24 attributes and their operational definitions; core attributes are grouped together and listed first. The table also shows the best identified data source for evaluation. The remaining attributes are grouped within person-oriented, community-oriented, structural and system performance categories.

TABLE 1.

Operational definitions of attributes of primary healthcare to be evaluated and consensus on best data source for evaluation

| Core Attributes | Best Data Source |

|---|---|

| First-Contact Accessibility: The ease with which a person can obtain needed care (including advice and support) from the practitioner of choice within a time frame appropriate to the urgency of the problem. | Patient |

| Comprehensiveness of Services: The provision, either directly or indirectly, of a full range of services to meet patients' healthcare needs. This includes health promotion, prevention, diagnosis and treatment of common conditions, referral to other providers, management of chronic conditions, rehabilitation, palliative care and, in some models, social services. | Patient, provider, administrative data |

| Relational Continuity: A therapeutic relationship between a patient and one or more providers that spans various healthcare events and results in accumulated knowledge of the patient and care consistent with the patient's needs. | Patient |

| Coordination (Management) Continuity: The delivery of services by different providers in a timely and complementary manner such that care is connected and coherent. | Patient |

| Interpersonal Communication: The ability of the provider to elicit and understand patient concerns, to explain healthcare issues and engage in shared decision-making, if desired. | Patient |

| Technical Quality of Clinical Care: The degree to which clinical procedures reflect current research evidence and/or meet commonly accepted standards for technical content or skill. | Provider, chart audit |

| Clinical Information Management: The adequacy of methods and systems to capture, update, retrieve and monitor patient data in a timely, pertinent and confidential manner. | Provider |

| Person-Oriented Dimensions | |

| Advocacy: The extent to which providers represent the best interests of individual patients and patient groups in matters of health (including broad determinants) and healthcare. | Patient |

| Cultural Sensitivity: The extent to which a provider integrates cultural considerations into communication, assessment, diagnosis and treatment planning. | Patient |

| Family-Centred Care: The extent to which the provider considers the family (in all its expressions), understands its influence on a person's health and engages it as a partner in ongoing healthcare. | Patient |

| Respectfulness: The extent to which health professionals and support staff meet users' expectations about interpersonal treatment, demonstrate respect for the dignity of patients and provide adequate privacy. | Patient |

| Whole-Person Care: The extent to which a provider elicits and considers the physical, emotional and social aspects of a patient's health and considers the community context in the patient's care. | Patient |

| Community-Oriented Dimensions | |

| Client/Community Participation: The involvement of clients and community members in decisions regarding the structure of the practice and services provided (e.g., advisory committees, community governance). | Patient, provider |

| Equity: The extent to which access to healthcare and good-quality services is provided on the basis of health needs, without systematic differences on the basis of individual or social characteristics. | All |

| Intersectoral Team: The extent to which the primary care provider collaborates with practitioners from non-health sectors in providing services that influence health. (Note: This dimension is relevant only to community models of primary care.) | Provider |

| Population Orientation: The extent to which primary care providers assess and respond to the health needs of the population they serve. (In professional models, the population is the patient population served; in community models, it is defined by geography or social characteristics.) | Patient, provider |

| Structural Dimensions | |

| Accessibility–Accommodation: The way primary healthcare resources are organized to accommodate a wide range of patients' abilities to contact healthcare providers and reach healthcare services (e.g., the organization of characteristics such as telephone services, flexible appointment systems, hours of operation and walk-in periods). | Patient |

| Informational Continuity*: The extent to which information about past care is used to make current care appropriate to the patient. | (Not assessed) |

| Multidisciplinary Team: Practitioners from various health disciplines collaborate in providing ongoing healthcare. | Provider |

| Quality Improvement Process: The institutionalization of policies and procedures that provide feedback about structures and practices and that lead to improvements in clinical quality of care and provide assurance of safety. | Provider |

| System Integration: The extent to which the healthcare unit organization has established and maintains linkages with other parts of the healthcare and social services system to facilitate transfer of care and coordinate concurrent care among different healthcare organizations. | Provider |

| System Performance | |

| Accountability: The extent to which the responsibilities of professionals, management and governance structures are defined, their performance is monitored and appropriate information on results is made available to stakeholders. | Provider |

| Availability: The fit between the number and type of human and physical resources and the volume and types of care required by the catchment population served in a defined period of time. | Administrative data |

| Efficiency/Productivity: Achieving the desired results with the most cost-effective use of resources. (This definition is non-operational.) | Administrative data |

This definition and best data source were not submitted to the consensus process but are included for completeness by general agreement of the research team.

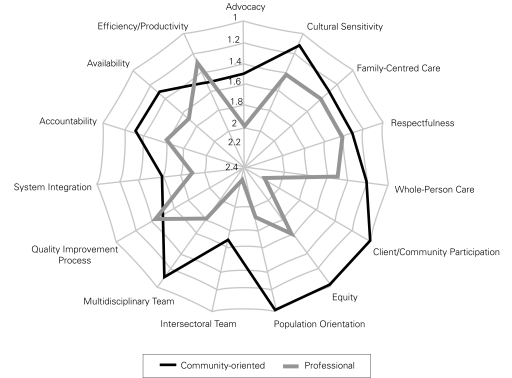

Figure 1 represents schematically the mean importance scores on non-core attributes for professional and community-oriented models (all core attributes are ranked as 1). Overall, attributes are assigned greater importance in the community-oriented than in the professional model. Ten attributes are classified as essential (rank 1.0–1.3) in the community-oriented model, compared to only one in the professional model (efficiency/productivity). No attributes ranked below important in community-oriented models, while three were judged only somewhat important for professional models (advocacy, intersectoral team and client/community participation). This is not to say that attributes did not rank high in the professional model. Nine were considered very important, but even those were rated as more important or essential to community models' performance. Two attributes (accessibility–accommodation and informational continuity) were added at the final face-to-face meeting with a subgroup of experts, and consequently were not scored for importance within organizational models of PHC. The others are ranked in order of importance first in the community-oriented model, then in the professional model. Three attributes – population orientation, client/community participation and equity – were unanimously ranked as essential in the community-oriented model. These would be considered core attributes of this model, with equity being very important also in professional models.

FIGURE 1.

Synthesis of ranking scores of non-core attributes across models

Table 2 highlights, for each of the attributes, the difference in importance between community-oriented and professional models. Attributes are ordered by the extent to which each was considered more important in the community-oriented model (determined by simple subtraction of the mean importance scores). A larger positive difference indicates that an attribute is relevant principally in community-oriented models, while negative values identify those more relevant in professional models; a score of zero indicates equal relevance in both (e.g., core attributes). From Table 2, we see that some attributes (such as client/community participation, population orientation, multidisciplinary team, equity, intersectoral team and advocacy) are relevant and of utmost importance in community-oriented models, and others (efficiency/productivity, quality improvement process) in professional models. Other attributes (such as system integration) are equally important in both.

TABLE 2.

Clustering of attributes according to discriminating power and relevance to both organizational models

| Ranking Difference between Models | Relevance to Both Models | |

|---|---|---|

| Client/community participation | 1.1 | − |

| Population orientation | 0.9 | − |

| Multidisciplinary team | 0.7 | + |

| Equity | 0.6 | + |

| Intersectoral team | 0.6 | − |

| Advocacy | 0.5 | − − |

| Availability | 0.4 | + |

| Cultural sensitivity | 0.3 | ++ |

| Accountability | 0.3 | ++ |

| Whole-person care | 0.3 | ++ |

| System integration | 0.3 | − |

| Family-centred care | 0.1 | ++ |

| Respectfulness | 0.1 | ++ |

| Quality improvement process | − 0.1 | + |

| Efficiency/productivity | − 0.2 | ++ |

| First-contact accessibility | 0 | +++ |

| Clinical information management | 0 | +++ |

| Technical quality of clinical care | 0 | +++ |

| Comprehensiveness of services | 0 | +++ |

| Continuity – coordination | 0 | +++ |

| Continuity − relational | 0 | +++ |

| Interpersonal communication | 0 | +++ |

Discussion and Conclusion

The experts identified seven core attributes that must be present in any model of primary care: first-contact accessibility, comprehensiveness of services, relational continuity, coordination (management) continuity, interpersonal communication, technical quality of clinical care and clinical information management. From an evaluation standpoint, it is critical to ensure we have appropriate tools to assess PHC performance in these core dimensions, which should always be assessed whatever model is under study or attribute is of interest. If an intervention's focus is, say, on multidisciplinary teams or accessibility–accommodation, then, in addition to examining improvement in that attribute, the evaluation process must ensure that this improvement does not occur at the expense of core attributes.

Our findings on the scoring of non-core attributes suggest that more is expected of community-oriented than professional models. Community-oriented models are expected to provide both a large scope of services and care that addresses health determinants and equity. Some person-oriented attributes (such as cultural sensitivity and whole-person care) and community-oriented attributes (such as equity and population orientation) ranked as truly essential to this model.

Interestingly, efficiency was not considered an essential attribute of community-oriented models. This is interesting because “[services] provided at a cost that communities can afford” – one of the most-repeated phrases from the Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care (WHO 1978) – is the inspiration for the community-oriented model. This result may reflect the Canadian experience with community health centres, which is that whatever they may achieve in community-oriented attributes, their productivity with respect to medical services is generally much lower than that of professional models (Pineault et al. 2009). On the other hand, a direct efficiency comparison with professional models may be inappropriate, given the community-oriented models' fundamentally different driving vision of achieving population health benefits rather than focusing on general medical services.

System performance attributes are very important in both models. Interestingly, accountability and availability of resources are seen as essential to community-oriented models, while efficiency/productivity and quality improvement process are more important in professional models.

The implication for evaluation of community-oriented PHC organizations is that a broad scope of measures is required to evaluate the full array of functions considered essential. Evaluation of professional models can address a narrower spectrum of attributes. This distinction further suggests that different standards of performance might be expected from community-oriented and professional models, and evaluative efforts should compare similar models on specific attributes that are most relevant to the model family, using specifically tailored measures. However, all models should be evaluated for core attributes. We mapped the operational definition of all 24 attributes to subscales in 13 unique instruments that evaluate care from the patient perspective (report available from the authors). We found that most core attributes – except technical quality of care – were well covered by these instruments, and this special issue of Healthcare Policy provides evaluators with valuable information to guide their choices between instruments.

Measuring achieved outcomes for expected attributes – and not measuring non-expected attributes – would provide an appropriate evaluation of performance. More specific attributes should be better at discriminating among organizations within each model, while attributes with similar rankings of relevance should be better at discriminating among models.

This work also highlights attributes that can be monitored as indicators of change during the process of shifting from one PHC model to another, as is currently occurring in many jurisdictions. This suggests that the aims of PHC reforms should inform the choice of attributes to measure. Attributes not traditionally seen as relevant to an organizational model should be measured if reforms involve moving away from traditional ways of organizing PHC.

We found that attributes, and consequently indicators, are not equally relevant for different organizational models. Therefore, current evaluative tools should be reviewed in accordance with the specific organizational models being evaluated to provide more relevant information to guide health reforms. In addition, targeting operational attributes of PHC that are core to all models, as well as at those that are specific to some models or that are the focus of model transformations or innovations, should be a guiding principle in the design of evaluation and performance assessment strategies.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on a presentation made during the North American Primary Care Research Group Conference in Quebec City on October 16, 2005. The authors, who accept full responsibility for the content of this paper, would like to thank anonymous participants for their comments and suggestions. Special thanks to Christine Beaulieu for research support throughout this survey.

This study was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Contributor Information

Jean-Frédéric Lévesque, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC.

Jeannie L. Haggerty, Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC.

Frederick Burge, Department of Family Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Marie-Dominique Beaulieu, Chaire Dr Sadok Besrour en médecine familiale, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC.

David Gass, Department of Family Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Raynald Pineault, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC.

Darcy A. Santor, School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON.

References

- Clair M. 2000. Les Solutions émergentes: Rapport et recommandations. Quebec, QC: Government of Quebec, Commission d'étude sur les services de santé et les services sociaux [Google Scholar]

- Government of Alberta 2001. A Framework for Reform: Report on the Premier's Advisory Council on Health. Don Mazankowski PC, OC, ed. ISBN 0-7785-1547-8 Report; ISBN 0-7785-1548-6 Appendices. 2001. Retrieved May 9, 2011. <http://www.assembly.ab.ca/lao/library/egovdocs/alpm/2001/132279.pdf>.

- Government of Ontario 2000. Looking Back, Looking Forward: The Ontario Health Services Restructuring Commission (1996–2000). A Legacy Report. Toronto: Ontario Health Services Restructuring Commission [Google Scholar]

- Government of Saskatchewan 2001. Caring for Medicare: Sustaining a Quality System. Regina: Saskatchewan Commission on Medicare [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty J., Burge F., Lévesque J.-F., Gass D., Pineault R., Beaulieu M.-D., Santor D. 2007. “Operational Definitions of Attributes of Primary Health Care: Consensus among Canadian Experts.” Annals of Family Medicine 5: 336–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby J.L., LeBreton M. 2002. The Health of Canadians – The Federal Role: Volume 6: Recommendations for Reform. Ottawa: Government of Canada, Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche P.-A., Beaulieu M.-D., Pineault R., Contandriopoulos A.-P., Denis J.-L., Haggerty J. 2003. Choices for Change: The Path for Restructuring Primary Healthcare Services in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation [Google Scholar]

- Pineault R., Lévesque J.-F., Roberge D., Hamel M., Lamarche P., Haggerty J. 2009. Accessibility and Continuity of Care: A Study of Primary Healthcare in Quebec. Research Report. Montreal: Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Public Health Department of the Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal and Charles LeMoyne Hospital Research Centre [Google Scholar]

- Romanow R.J. 2002. Building on Values – The Future of Health Care in Canada. Final Report. Ottawa: Government of Canada, Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 1978. Primary Health Care: Report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. Geneva: Author [Google Scholar]