Abstract

Transmission of HIV-1 and drug resistance continue to occur at a considerable level in Italy, influenced mainly by changes in modality of infection. However, the long period of infectivity makes difficult the interpretation of epidemiological networks, based on epidemiological data only. We studied 510 naive HIV-1-infected individuals, of whom 400 (78.4%) were newly diagnosed patients with an unknown duration of infection (NDs), with the aim of identifying sexual epidemiological networks and transmitted drug resistance (TDR) over a 7-year period. Clusters were identified by Bayesian methods for 412 patients with B subtype; 145 individuals (35.2%) clustered in 34 distinct clades. Within epidemiological networks males were 93.1% (n=135); the same proportion of patients has been infected by the sexual route; 62.1% (n=90) were men having sex with men (MSM) of whom 67.8% (n=61) were NDs. Among heterosexuals (n=44), males were predominant (79.5%, n=35) and 77.3% (n=34) were NDs. TDR in clusters was 11.7 % (n=17), of whom 76.5% (n=13) was found in MSM. TDR was predominantly associated with NRTI resistance in individuals with chronic infection (n=11). A high prevalence of epidemiological networks has been found in the metropolitan area of Milan, indicating a high frequency of transmission events. The cluster analysis of networks suggested that the source of new infections was mainly represented by males and MSM who have long lasting HIV-1 infection. Notably, the prevalence of resistance-conferring mutations was higher in chronically infected patients, carrying mainly resistance to thymidine analogs, the backbone of first antiretroviral (ARV) generation. Intervention strategies of public health are needed to limit HIV-1 transmission and the associated TDR.

Introduction

Despite the effort to control the transmission of HIV-1 through antiretrovirals (ARVs) and prevention strategies, HIV infection remains a major public health issue in Europe, with evidence of relevant epidemic transmission of HIV in several European countries. Overall, despite incomplete reporting, the rate of newly diagnosed cases of HIV registered per million population has more than doubled from 44 per million in 2000 to 89 per million in 2008.1

Furthermore, the extensive usage of ARVs in regimens with limited potency or in scarcely adherent patients has allowed the emergence of a very high prevalence of secondary resistance for nucleoside and nonnucleoside reverse transciptase (70–78% NRTIs and 31–40% NNRTIs) and 37–47% protease inhibitors (PIs) as documented by several population-based studies.2–4 Although ARV-experienced patients carrying resistant variants are thought to be the main source for naive subjects, seroconverters, infected in turn with resistant variants, may contribute substantially to the transmission of such strains.5

Recent estimates of transmitted drug resistance (TDR) in newly infected individuals are about 10% in Europe and the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy in these patients is compromised when first line regimens contain drug(s) to which HIV-1 has a reduced susceptibility.6,7

The spread of viral variants carrying resistance mutations is highly dependent on several variables that define the demography of local HIV-1 epidemics and their evolution over time.8 Among these, risk-taking behaviors of both infected and uninfected individuals, interactions between transmission groups (i.e., prostitution, bisexuality, and transexuality), and increasing prevalence of non-B subtypes among newly diagnosed cases seem to be important variables.9–12 The most recent Italian data (2008) from the Centro Operativo AIDS indicates that more than 2000 new diagnoses have occurred, equivalent to an incidence of 6.7 per 100000 residents and characterized by a marked decrease of proportions of injecting drug users (IDUs) and a corresponding increase in sexual transmission, either in heterosexuals (HETs) or in men having sex with men (MSM).13

We first assessed the prevalence of TDR, as well as non-B subtypes, in newly diagnosed individuals and their association with the main epidemiological variables to characterize the HIV-1 epidemic structure within a dense sample of an Italian urban population (Milan and surrounding areas) in recent years.

As epidemiological patterns can be inferred by HIV-1 pol sequence data,9 we then used phylogenetic clustering methods for HIV-1 subtype B to trace potential contact chains, identify their risk behaviors, and date their occurrence. The impact of epidemiological networks on TDR frequency may explain its persistence in newly diagnosed individuals and its understanding may help clinicians in the selection of a first ARV regimen based on resistance screening, as well as the health policymakers, in designing prevention strategies.

Materials and Methods

Study population

We consecutively enrolled 510 patients who received a new diagnosis of HIV-1 infection between 2002 and 2008, who were naive to antiretroviral therapy, and had a genotypic resistance test performed within 1 month after diagnosis. These patients represent a consecutive series of individuals followed at the Clinic of Infectious Diseases and Immunopathology, ‘L. Sacco’ Hospital, Milan, Italy.

A questionnaire was used to collect demographic (gender, age, ethnicity), epidemiological (date of HIV-1 diagnosis, modality of infection), clinical (CDC stage), immunological (CD4 and CD8 count, and CD4/CD8 ratio), and virological data (HIV-1 RNA levels in plasma) collected at the time of diagnosis. All subjects signed an informed consent to allow the input of these parameters in a dedicated database. The Ethic Committee of ‘L. Sacco’ Hospital has approved the study. Among patients, seroconverters (SCs) were defined on the basis of an estimated date of seroconversion (midpoint between the last negative and the first positive HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay within the past 18 months) or the presence of an acute retroviral syndrome. For the remaining newly diagnosed individuals (NDs) the duration of infection was undefined.

Drug resistance testing

The genotypic resistance tests were performed at two sites, regularly taking part in external quality control programs, on plasma samples collected before the initiation of antiretroviral therapy through commercially available assays [ViroSeq v2 kit, Abbott Diagnostics (n=127) and Trugene System (n=383)]. Protease and reverse transcriptase (RT) pol sequences were generated after RNA extraction, RT-PCR amplification, and automated sequencing. Drug-related resistance was defined by the presence of at least one resistance mutation from the WHO-recommended SDRM (Surveillance Drug Resistance Mutations) list. This list has 93 mutations including 34 NRTI-associated resistance mutations at 15 reverse transcriptase positions, 19 NNRTI-associated resistance mutations at 10 reverse transcriptase positions, and 40 PI-associated resistance mutations at 18 protease positions (available at http://hivdb.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/AgMutPrev.cgi; 08 July 2011, date last accessed).

Subtyping of protease and RT sequences

Protease and RT sequences generated by resistance testing were trimmed to equivalent length (863 bp) and aligned with representative sequences available in the Los Alamos database (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov) using the CLUSTAL algorithm implemented in BioEdit version 5.0.9 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/page2.html). Two to five strains representative of each of the 9 pure subtypes (A–D, F–H, J, and K) and 49 known circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) were chosen as references. Subtype or CRF assignment was performed using SEQBOOT, DNADIST, NEIGHBOR, and CONSENSE programs implemented in the PHYLIP package version 3.67 (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html). Phylogenetic trees were generated with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method based on the Kimura two-parameter distance model. The empirical transition/transversion ratio was estimated for the sequence dataset with software TreePuzzle version 5.0 (http://www.tree-puzzle.de/). Bootstrap support (1000 replicates) for the different taxas of the NJ tree was calculated. For bootstrap values under 85, the SimPlot software version 2.5 (http://www.med.jhu.edu/deptmed/sray/download) was used to generate similarity plots and bootscans to check for possible unique recombinants.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on 412 sequences of B subtype. One patient sequence was excluded because of insufficient length. The Bayesian phylogenetic tree was reconstructed by means of MrBayes14 using a general-time reversible (GTR) model of nucleotide substitution, a proportion of invariant sites, and gamma distributed rates among sites. A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) search was made for 10×106 generations using tree sampling every 100th generation and a burn-in fraction of 50%. Statistical support for specific clades was obtained by calculating the posterior probability of each monophyletic clade, and a posterior consensus tree was generated after a 50% burn-in. Clades with a posterior probability of 1 were considered epidemiological clusters. The posterior consensus tree obtained by means of MrBayes was used as the starting tree.

Dated tree, evolutionary rates, and population growth were coestimated by using a Bayesian MCMC approach (Beast version 1.4.8. http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk)15 implementing a GTR+Invariant+Gamma model. Different parametric demographic models (a constant population size, exponential and logistic growth) and a nonparametric Bayesian skyline plot (BSP) were compared under strict and relaxed clock conditions. The best model was selected by means of a Bayes factor (BF, using marginal likelihoods) implemented in Beast.15,16 In accordance with Kass and Raftery,17 the strength of the evidence against Hypothesis 0 (H0) was evaluated as follows: 2 ln BF <2 no evidence, 2–6 weak evidence, 6–10 strong evidence, and >10 very strong evidence. A negative value indicates evidence in favor of H0. Only values ≥6 were considered significant. Chains were conducted for at least 30×106 generations, and sampled every 3000 steps. Convergence was assessed on the basis of the effective sampling size (ESS) after a 10% burn-in, using Tracer software version 1.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/). Only parameter estimates with ESS >200 were accepted. Uncertainty in the estimates was indicated by 95% highest posterior density (95% HPD) intervals. The trees were summarized in a target tree by the Tree Annotator program included in the Beast package by choosing the tree with the maximum product of posterior probabilities (maximum clade credibility) after a 50% burn-in.

To exclude false clustering due to convergent evolution we confirmed the analysis in a codon-stripped dataset where 43 amino acids associated with major HIV-1 drug resistance mutations, according to the SDRM list, were removed.

Statistical methods

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and comparisons between groups were performed using the χ2 or the Fisher exact test. The Cochrane–Armitage test was used to analyze temporal trends. For all the analyses an α error of 5% was considered. Analyses were performed using the SAS software package v.9.1.

Results

Characteristics of population

We studied 510 patients who received a diagnosis of HIV-1 infection between 2002 and 2008. Patient distribution was 8.2%, 12.2%, 12.7%, 18.8%, 15.5%, 19%, and 13.5% in the study interval.

Overall, 110 individuals (21.6%) seroconverted within 18 months before the diagnosis; a proportion of 82.9% (n=421) were of white descent; MSM, HETs, IDUs, and other or unknown risk were 50.2% (n=256), 42.4% (n=216), 2.9% (n=15), and 4.5% (n=23), respectively. Male-to-female ratio was 5.1 (427: 83). Demographic, virological, and immunological data of this population are shown in Table 1 according to B and non-B subtype carriage and duration of infection.

Table 1.

Demographic, Virological, and Immunological Data on Newly Diagnosed HIV-1 Individuals in the 2002–2008 Period

| |

Patients with B variants (n=413) |

Patients with non-B variants (n=97) |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | SCsa(n=98) | NDsb(n=315) | SCsa(n=12) | NDsb(n=85) | Total (n=510) |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | |||||

| White | 93.9 (92) | 83.5 (263) | 91.7 (11) | 67.1 (57) | 82.9 (423) |

| Otherc | 6.1 (6) | 16.5 (52) | 8.3 (1) | 32.9 (28) | 17.1 (87) |

| Risk factors, % (n) | |||||

| Men having sex with men | 69.4 (68) | 52.1 (164) | 50 (6) | 21.2 (18) | 50.2 (256) |

| Heterosexual contacts | 25.5 (25) | 39.4 (124) | 41.7 (5) | 72.9 (62) | 42.4 (216) |

| Injecting drug users | 2 (2) | 3.5 (11) | 0 | 2.4 (2) | 2.9 (15) |

| Otherd | 1 (1) | 1.3 (4) | 8.3 (1) | 1.2 (1) | 1.4 (7) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 3.8 (12) | 0 | 2.3 (2) | 3.1 (16) |

| Gender, % (n) | |||||

| Male | 90.8 (89) | 85.7 (270) | 83.3 (10) | 68.2 (58) | 83.7 (427) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (min-max) | 35 (19–62) | 38 (19–77) | 40 (30–64) | 36 (25–70) | 37 (19–77) |

| (25th–75th percentile) | 29–41 | 31–435 | 31–42 | 31–43 | 31–43 |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) | |||||

| Median (min-max) | 467 (17–1305) | 292 (2–1870) | 283 (60–977) | 234 (3–1404) | 326 (2–1870) |

| (25th–75th percentile) | 350–607 | 88–499 | 221–539 | 93–438 | 113–519 |

| HIV RNA (copies/ml) | |||||

| Median (min-max) | 4.7 (2.6–6.5) | 4.7 (1.7–5.7) | 5.2 (3.8–5.7) | 4.7 (2.9–5.7) | 4.7 (1.7–6.5) |

| (25th–75th percentile) | 4.2–5.3 | 4.1–5.2 | 4.7–5.7 | 4.2–5.2 | 4.2–5.3 |

SCs, subjects with a seroconversion date defined by HIV antibody testing in the past 18 months or with an acute retroviral syndrome.

NDs, newly diagnosed individuals with an undefined duration of infection.

Black Africans, Asians, Latin Americans.

Other, transfusion, vertical transmission, unknown risk.

Epidemiological correlates of HIV-1 infection

The proportion of nonwhite patients differed significantly in NDs and SCs (80/400, 20% and 7/110, 6.4%, respectively; p<0.0001). Distribution of MSM was prevalent among SCs (74/110, 67.3%), while HETs were predominant among NDs (186/400, 46.5%) (p=0.0003). Male gender was comparable in NDs and SCs (328/400, 82% vs. 99/110, 90%). Four-hundred and thirteen individuals (81%) carried a B subtype as established by the analysis of the pol gene.

The distribution of non-B variants was higher in NDs compared to SCs (85/400, 21.2% vs. 12/110, 10.9%; p=0.0135). The detection of non-B variants was associated with an ethnicity other than white as 33.3% (29/87) compared to 16.1% (68/423) of non-B strains were carried by subjects classified according to ethnicity (p=0.0002). The modality of infection was distributed differently in patients carrying a B or non-B clade. Among individuals with B subtype, MSM accounted for 56.2% (232/413), while among those with variants other than B, HETs were predominant (69.1%, 67/97; p<0.0001). Woman with non-B variants were higher compared to those with B strains (29/97, 29.9% vs. 54/83, 13.1% ; p<0.0001).

Overall, the age of patients did not differ according to the clade (median 37 and 36 years, min-max: 30–77 and 31–70 years for B and non-B strains, respectively). Median CD4 cell counts were lower in patients with non-B variants (253, min-max: 3–1404) compared to those carrying B strains (346, min-max: 2–1870), while HIV-1 RNA was comparable in the two groups of subjects (4.7 and 4.7, min-max: 1.7–6.5 and 2.8–5.7 for B and non-B subtypes, respectively). Two significant temporal trends were observed in the overall population. SCs decreased from 42.9% (18/42) to 11.6% (8/69) (p<0.0001) and individuals carrying non-B subtype increased from 9.5% (4/42) to 23.2% (16/69) (p=0.039) in the study period.

Among the 413 patients carrying the B subtype, the comparison of the ethnicity and time from infection indicated that the proportion of SCs in whites was higher compared to nonwhites (25.9%, 92/355 vs. 10.3%, 6/58; p=0.0098). The distribution of MSM was higher in SCs (68/98, 69.4%) compared to NDs (164/315, 52.1%) (p=0.010). No differences were observed in SCs compared to NDs regarding gender distribution and median HIV-1 RNA levels, while age was lower (p=0.0084) and CD4 absolute counts were higher (p<0.0001) in SCs compared to NDs (Table 1).

Transmitted HIV-1 resistance

Overall, TDR was detected in 66/510 subjects (12.9%). Mutations associated with NRTI, NNRTI, and PI resistance were 8.0% (n=41), 4.7% (n=24), and 2.5% (n=13), respectively. Resistance to two or three classes of antiretrovirals was 1.2% (6/510, 4 for NRTIs+NNRTIs, 1 for NRTIs+PIs, and 1 for NNRTIs+PIs) or 0.6% (n=3).

Of the 66 patients with resistance mutations, 65.1% (43/66) carried one mutation for NRTIs (n=19) or NNRTIs (n=16) or PIs (n=8), 21.2% (n=14) two or three mutations, and 13.6% (n=9) more than three mutations. Among these the most common were T215 Y/F and revertants (36.4 %), followed by M41L (21.2%) and K103N (19.7%).

Resistance to any antiretroviral was higher in SCs (19/110, 17.3%) compared to NDs (47/400, 11.8%); however this difference was significant only for NNRTI (10/110, 9.1% vs. 13/400, 3.3%, respectively; p=0.016).

Globally, no trend for an increase or a decrease of TDR was observed over time either in the overall population or in individuals carrying the B clade. However, the prevalence of resistance to any antiretroviral was higher in patients carrying the B (60/413, 14.5%) vs. non-B clade (6/97, 6.2%) (p=0.033). The proportions of class resistance for patients with B subtype did not differ from those of patients carrying non-B strains: 9% (n=37) vs. 4.1 (n=4) for NRTIs, 5.1% (n=21) vs. 3.1% (n=3) for NNRTIs, and 2.7% (n=11) vs. 2.1% (n=2) for PIs, respectively.

No association was found between resistant strains and ethnicity (TDR was 57/421, 13.5% and 9/87, 10.3% in whites vs. nonwhites). A trend for an association between primary resistance and homosexual modality of infection was observed as resistant variants were 16.4% (42/256) in MSM and 8.8 % (19/216) in HETs, p=0.069; men with resistance were 14.3% (61/427) compared to women (5/83, 6%), thus male gender was weakly associated with TDR (p=0.047) in the whole population.

Class-related substitutions were detected at comparable levels in patients with B or non-B subtypes either SCs or NDs (data not shown).

No predictors of TDR were identified by a logistic regression model evaluating time of infection, ethnicity, mode of infection, gender, and subtype in the whole population (data not shown).

Among the 413 patients carrying the B subtype no differences were observed in the proportion of resistant mutations and time from infection, ethnicity, risk factor, and gender (data not shown).

Phylogenetic analysis of B subtype isolates

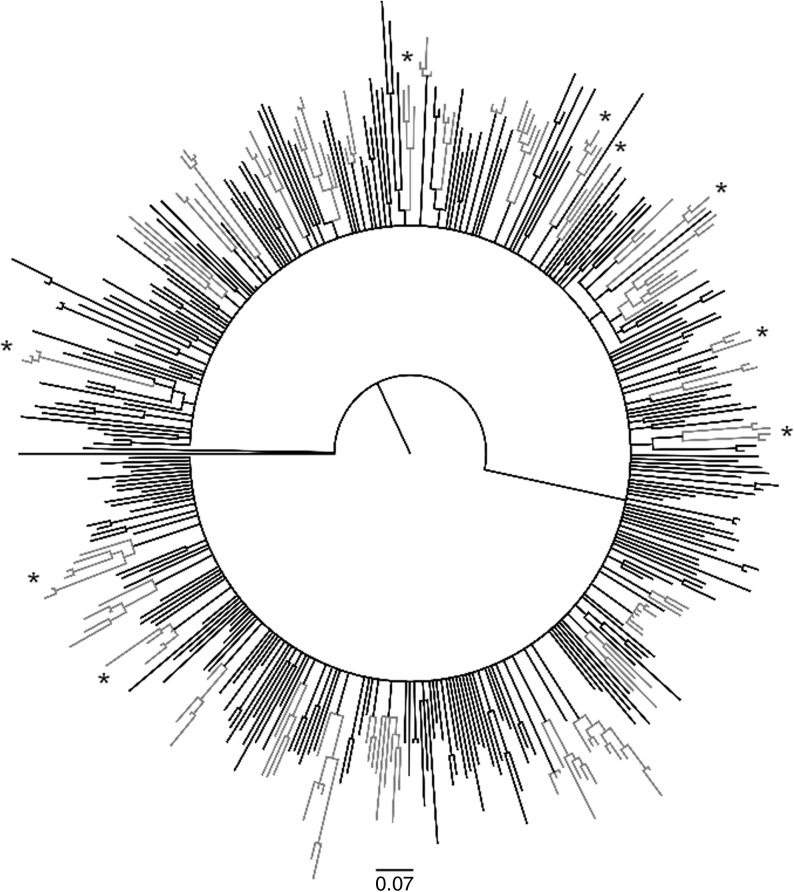

The phylogenetic tree of 412 HIV-1 B sequences is shown in Fig. 1. On the basis of MrBayes starting tree we identified 34 transmission clusters with a posterior probability of 1. Clusters, containing at least three sequences, involved 145 (145/412, 35.2%) patient isolates. The number of sequences in clusters ranged from 3 to 8.

FIG. 1.

Starting tree obtained with the MrBayes program showing 34 identified clusters (gray color). Clusters involving sequences carrying mutations associated with resistance to antiretrovirals (ARV) are marked with an asterisk.

The tree topology indicated that of the 145 clustering patients 41 were seroconverters (28.3%). We did not found a significant association between subjects within clusters and the year of diagnosis either considering the entire population or patients with unknown duration of infection and seroconverters. Only one (1/34, 2.9%) cluster was represented entirely by SCs, while 12 (12/34, 35.3%) clades included only NDs (data not shown). As a consequence, a highly significant association was found between newly diagnosed subjects and homogeneous clusters (n=43, 41.3% NDs vs. n=3, 7.3% SCs; p<0.0001).

Of the 58 patients of nonwhite descent with B strains 14 patients were present in 10 different clusters (14.7%, 14/145). The comparison between patients according to ethnicity indicated that a higher frequency of whites could be found within clusters (24.1%, 14/58 vs. 37%, 131/354), although this difference was not significant (p=0.07).

Regarding the modality of infection, we detected a significantly higher proportion of MSM than HETs in clusters (n=98, 67.6% MSM vs. n=44, 30.4% HETs; p=0.03). Ten clusters (10/34, 29.4%) involved only MSM, while only two clades (2/34, 5.9%) included HETs only (data not shown). A trend for the association of MSM (n=36) and homogeneous clusters was detected (36.7% MSM vs. 20.5% HETs, n=9; p=0.07). A significantly higher proportion of males (37.7%, 135/358 males vs. 18.5%, 10/54 females, p=0.005) was found in clusters.

HIV-1 clustering lineages with antiretroviral resistant mutations

Among the 145 patients involved in epidemiological clusters, 18 subjects (12.4%) carried transmitted resistant strains. Twelve patients, three patients, and one patient carried NRTI, NNRTI, and PI mutations alone. Two individuals had NRTI+NNRTI changes or NNRTI+PI substitutions. These data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Epidemiological Networks of Patients Carrying Antiretroviral-Associated Mutations

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Drug resistance mutations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Sampling date | Time of infection | Ethnicity | Mode of infection | Gender | NRTIsa | NNRTIsa | PIsa |

| 4 | 2007 | NDb | White | MSMc | M | — | — | — |

| 4 | 2007 | ND | Nonwhite | MSM | M | — | G190A | V82VA |

| 4 | 2008 | ND | Nonwhite | MSM | M | — | G190A | — |

| 9 | 2007 | ND | White | — | M | — | — | — |

| 9 | 2007 | ND | White | HETd | F | — | — | — |

| 9 | 2003 | ND | White | — | M | V75AV | — | — |

| 13 | 2008 | ND | White | MSM | M | — | — | — |

| 13 | 2006 | ND | White | MSM | M | — | — | — |

| 13 | 2007 | ND | White | HET | M | — | — | — |

| 13 | 2003 | SCe | White | MSM | M | T215D | — | — |

| 14 | 2003 | ND | White | HET | M | — | — | V82FLV |

| 14 | 2007 | ND | Nonwhite | MSM | M | — | — | — |

| 14 | 2002 | ND | White | HET | F | — | — | — |

| 16 | 2007 | ND | White | HET | M | — | — | — |

| 16 | 2008 | ND | White | MSM | M | M184V | — | — |

| 16 | 2005 | SC | White | HET | M | — | — | — |

| 18 | 2008 | SC | White | MSM | M | — | — | — |

| 18 | 2005 | SC | White | MSM | M | — | G190A | — |

| 18 | 2004 | SC | White | MSM | M | — | G190A | — |

| 19 | 2007 | ND | Nonwhite | MSM | M | T215D | — | — |

| 19 | 2008 | ND | Nonwhite | MSM | M | T215E | — | — |

| 19 | 2006 | ND | White | MSM | M | T215D | — | — |

| 19 | 2005 | ND | White | MSM | M | — | — | — |

| 31 | 2003 | SC | White | HET | M | — | — | — |

| 31 | 2005 | SC | White | HET | F | — | — | — |

| 31 | 2007 | ND | Nonwhite | HET | F | — | — | — |

| 31 | 2003 | SC | White | MSM | M | — | — | — |

| 31 | 2006 | ND | White | MSM | M | M184V | K101KE | — |

| 34 | 2007 | ND | White | MSM | M | K219Q | — | — |

| 34 | 2003 | ND | White | MSM | M | K219Q | — | — |

| 34 | 2007 | ND | White | HET | F | K219Q | — | — |

| 34 | 2006 | ND | White | MSM | M | D67N, K219Q | — | — |

| 34 | 2006 | ND | White | MSM | M | D67N, K219Q | — | — |

| 34 | 2007 | ND | White | OTHf | M | K219KQ | — | — |

NRTIs, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTIs, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PIs, protease inhibitors.

NDs, newly diagnosed individuals with an undefined duration of infection.

MSM, men having sex with men.

HET, heterosexuals.

SCs, subjects with a seroconversion date defined by HIV antibody testing in the past 18 months or with an acute retroviral syndrome.

Other, transfusion, vertical transmission, unknown risk.

Of clusters 26.5% (9/34) involved sequences carrying mutations associated with resistance to ARV, as shown in Fig. 1. No difference could be seen in the distribution of SCs or NDs in clusters of sequences carrying resistant mutations (n=3, 7.3% SCs vs. n=15, 14.4% NDs). The proportions of whites and nonwhites with resistant variants differed slightly (14/131, 10.7% vs. 4/14, 28.6%, respectively; p=0.07).

Among patients carrying TDR a trend toward involvement in epidemiological clusters for MSM (n=15) compared to HETs (n=2) was detected (15.3% vs. 4.5%, respectively; p=0.08), while the gender did not correlate with resistant clusters (17/135, 12.6% males vs. 1/10, 10% females).

Dating of epidemiological networks

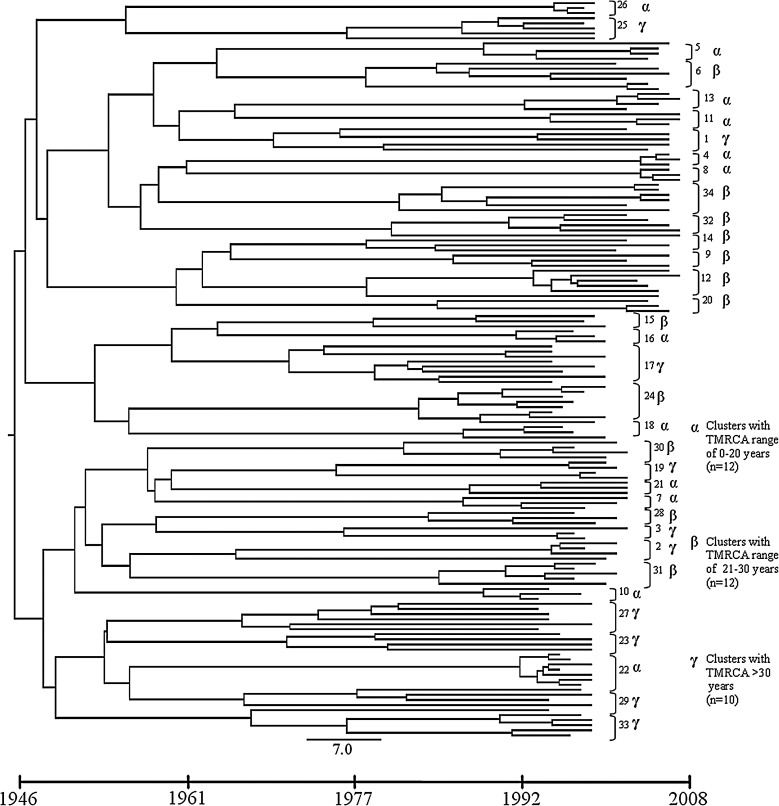

By using the Beast program, we next performed a phylodynamic analysis of the clustering sequences. The dated tree is shown in Fig. 2. A mean evolutionary rate of 1.22×10−3 (range 1.82×10−3–7.32×10−4). Substitutions/site/year was estimated for the HIV-1 pol sequences under evaluation. On the basis of this evolutionary rate we estimated the time of the most common recent ancestor (TMRCA) of the entire tree. The root of the tree was about 66.5 years before 2008 (95% HPD 32.2–82). Although the tree topology seemed to suggest multiple introduction events, sustained by two subclusters with two subsubclusters each, no significant posterior probability supported this observation.

FIG. 2.

Dated tree showing clustering sequences. Cluster numbers are shown on the right. The time line scale is displayed underneath the tree.

Based on TMRCA indicated by the tree (26.5 years mean, range 3.7–41.7), patient sequences were almost equally distributed over the past 40 years. On the temporal time scale, three sets of clusters were observed. The first set (α) ranged from 0 to 20 years and encompassed 12 clusters, the second (β) including 12 clusters ranged from 21 to 30 years, and the third (γ) included 10 clusters more than 30 years old (Fig. 2).

Patients carrying transmitted resistance had a significantly lower median TMRCA compared to those with a wild-type virus (26.3 years, range 11.9–41.7 vs. 27, range 3.7–32.3; p=0.04), implying that these subjects acquired HIV infection more recently.

We then looked for possible associations between estimated time of sequences and ethnicity, risk factor, gender, age of patients, and TDR. No significant associations were found between the TMRCA and these factors.

The 18 patients carrying transmitted resistant strains were involved in nine significant clusters (9/34, 25.5%, Fig. 3). The mean TMRCA for resistant clusters was 20.7 years (range 3.7–32.3). According to the estimated time, the nine clusters originated between 1976 [95% HPD 14.4–43.2 (cluster #19)] and 2004 [95% HPD 1.4–6.6 (cluster #4)].

FIG. 3.

Clusters involving resistant variants. Cluster numbers are shown on the right. The time line scale is displayed underneath the clusters.

Six out of nine clusters involved NDs only; NRTI mutations alone were present in five of them. The most frequently detected mutations were those related to NRTIs (six 219Q, four 215 revertants, two 184V, one 75V), dated from 1976 to 1992, followed by those associated with NNRTIs (four 190A and one 101E). Interestingly, patients in the same cluster could either carry or not carry the same mutations or the same substitution profile; in only one clade, strains with the 219Q mutation were present in all patients and two of them also carried the 67N (cluster #34). This cluster included samples enrolled from 2003 to 2007 from six drug-naive patients with chronic infection. The persistent 215 D/E revertants were carried by three out of four patients in clade #19, one of the oldest among resistant clusters. Two 184V were identified in clade #16 and #31; the first was found in a patient with an unknown duration of infection previously treated with lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B and the second in a seroconverter. Sequences of a cluster encompassing only seroconverters (#18) harbored an NNRTI-associated change (190A). A single PI-related mutation (82 F/L) was detected in cluster #14, which being dated in 1977 may be a consequence of HIV-1 natural variation.

Discussion

We analyzed a set of sequences from drug-naive recently or chronically HIV-1-infected individuals to characterize ethnicity, modality of infection, gender distribution, main circulating subtype, and primary drug resistance occurring for the HIV-1 epidemic in the highly prevalent Italian area of Milan since the early 2000s. By means of phylogenetic approaches we studied in detail the potential epidemiological chains, including the transmission of resistant variants, in a dense sample of patients living in a restricted geographic area, who acquired HIV-1 through sexual transmission in more than 90% of cases. Among the epidemiological correlates of the overall newly diagnosed subjects three significant temporal trends could be highlighted, indicating (1) a decline of patients diagnosed at seroconversion over time, (2) a considerable increase in nonwhite ethnicity, (3) a marked spread of non-B subtypes in Italian individuals, and (4) a stable burden of TDR (about 10%) despite the large ARV usage of recent years. These findings are in agreement with those reported in several European studies where limited initiatives are taken to prevent the spread of HIV-1 infection, leading to a large proportion of individuals unaware that they are infected, and migration flows that continue to occur from HIV-1 endemic areas.18–20 The incomplete effect of ARVs at the population level may account for the considerable levels of primary resistance due to some extent to patients experiencing therapy failure. However, the decrease of seroconversions may be explained by the new potent drugs that are used in first line regimens at present.4

Despite the decrease of seroconversion detection, among patients carrying the B subtype about one of four had a recent infection, of whom about 70% were MSM. Noteworthy, MSM were prevalent either among seroconverters or individuals with a chronic infection indicating a peculiar trait of sexual transmission in our case file.

The prevalence of TDR in patients infected with subtype B, comparable to that detected in recent European and national studies, was associated with recent infection for the NNRTI class and, to a lesser extent, with the homosexual modality of infection.

The phylogenetic structure of the epidemics in the relatively closed metropolitan area of Milan indicated that more than one-third of patients could be identified in contact networks implying a strong signal for a cluster distribution as previously reported for the spread of HIV-1 subtype B in Western Europe and North America.21,22 According to the demographic characteristics of our case file, most clustering patients had mainly an unknown duration of infection and were white males with a homosexual modality of infection. The frequency of contact networks was high despite the probable underestimation related to incomplete data due to intervening individuals not sampled. Nevertheless, as drug resistance may represent a molecular tracer, our finding of a comparable proportion of strains with resistant mutations among clustering (12.4%) and nonclustering patients (14.2 %) supports our analysis.

The tree topology, showing some degree of internal structure, coupled with the time scale estimation, suggested that multiple events of viral introduction occurred since the early 1970s. Moreover, dated phylogeny reconstruction provided insights into the occurrence of resistance transmission. Based on the time-scaled phylogenies, clades originated between 1968 (cluster #33) and 2004 (cluster #4) in concert with the introduction of HIV-1 in Europe, as was the case for the United Kingdom and France.9,23

Of note, one out of four clusters encompassed patients with resistant variants. Interestingly, a large cluster (cluster #34), dated around 1981 and mainly including MSM, showed the same resistance mutation (219Q) in all of the lineages. This finding reflects the wide usage of thymidine analogs in suboptimal regimens that led to the emergence and persistence of such variants.

According to the time-scaled phylogenies, we found that three of nine drug-resistant lineages originated between the mid-1990s and late 2000s (clusters #13, #4, and #16), which corresponds to the early years of ARV usage and to the time when the transmission of drug-resistant mutations was at its highest level in Europe and in the United States.24

We found that the prevalence of transmitted drug resistance was not significantly lower in recently infected individuals compared to patients with chronic infection, not supporting a reduction in transmitted resistance in the metropolitan area of Milan. A possible bias can be due to the disproportionate frequency of patients with chronic infection in our case file; however, the considerable number of patients and the relatively high density of sample supported this finding. Moreover, our results are in agreement with recent reports on TDR from several European cohorts.11,25,26,6,27,28

Several reports indicate that the number of new diagnoses of HIV infection is either stable or increasing in some developed countries with a rising incidence in MSM.1,2 This epidemic among MSM continues despite the widespread availability of effective antiretroviral therapy and requires specific interventions.

A number of factors such as changes in ethnicity and risk categories, time of infection, and ARV efficacy confer a complex picture to TDR, although a larger case file could identify additional associations between TDR and epidemiological correlates. Our data on contact networks of HIV-1 transmission seem, at least in part, driven by the same determinants. Overall, our findings provide new insights to strengthen the surveillance system for HIV-1 and the planning of prevention programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients included in the study. This work has been partially supported by PRIN (Programmi di Ricerca Scientifica di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale), grant 2005064042 and Programma Nazionale AIDS 2006, grant 30G.44 to C.B.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.ECDC: Surveillance Report. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe. 2008. http://www.eurohiv.org/ http://www.eurohiv.org/

- 2.Scott P. Arnold E. Evans B, et al. Surveillance of HIV antiretroviral drug resistance in treated individuals in England: 1998–2000. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:469–473. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caramma I. Violin M. Velleca R, et al. Study of antiretroviral resistance in treated patients with virological failure (START study) Temporal trends of class resistance evaluated in patients failing last HAART. XVI International HIV Drug Resistance Workshop. Jun 12–16, 2007. Barbados, West Indies. Abstract 53.

- 4.Di Giambenedetto S. Bracciale L. Colafigli M, et al. Declining prevalence of HIV-1 drug resistance in treatment-failing patients: A clinical cohort study. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:835–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner BG. Roger M. Routy JP, et al. High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:951–959. doi: 10.1086/512088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The SPREAD programme. Transmission of drug-resistant HIV-1 in Europe remains limited to single classes. AIDS. 2008;22:625–635. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f5e062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little SJ. Holte S. Routy JP, et al. Antiretroviral-drug resistance among patients recently infected with HIV. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:385–394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pillay D. Current patterns in the epidemiology of primary HIV drug resistance in North America and Europe. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:695–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hueé S. Pillay D. Clewley JP. Pybus OG. Genetic analysis reveals the complex structure of HIV-1 transmission within defined risk groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4425–4429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407534102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis F. Hughes GJ. Rambaut A. Pozniak A. Leigh Brown AJ. Episodic sexual transmission of HIV revealed by molecular phylodynamics. PLoS Med. 2008;5:392–402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouyos RD. von Wyl V. Yerly S, et al. Molecular epidemiology reveals long-term changes in HIV type 1 subtype B transmission in Switzerland. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1488–1497. doi: 10.1086/651951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yerly S. Junier T. Gayet-Ageron A, et al. The impact of transmission clusters on primary drug resistance in newly diagnosed HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2009;23:1415–1423. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d40ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Not Ist Super Sanità. www.iss.it 2007;23(Suppl 1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huelsenbeck JP. Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drummond AJ. Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suchard MA. Weiss RE. Sinsheimer JS. Bayesian selection of continuous-time Markov chain evolutionary models. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1001–1013. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kass RE. Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Statist Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riva C. Lai A. Caramma I, et al. Transmitted HIV Type 1 drug resistance and non-B subtypes prevalence among seroconverters and newly diagnosed patients from 1992 to 2005 in Italy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26:41–49. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balotta C. Facchi G. Violin M, et al. Increasing prevalence of non-clade B HIV-1 strains in heterosexual men and women, as monitored by analysis of reverse transcriptase and protease sequences. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:499–505. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200108150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai A. Riva C. Marconi A, et al. Changing patterns in HIV-1 non-B clade prevalence and diversity in Italy over three decades. HIV Med. 2010;11:593–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker PR. Pybus OG. Rambaut A. Holmes EC. Comparative population dynamics of HIV-1 subtypes B and C: Subtype-specific differences in patterns of epidemic growth. Infect Genet Evol. 2005;5:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callegaro A. Svicher V. Alteri C, et al. Epidemiological network analysis in HIV-1 B infected patients diagnosed in Italy between 2000 and 2008. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paraskevis D. Pybus O. Magiorkinis G, et al. Tracing the HIV-1 subtype B mobility in Europe: A phylogeographic approach. Retrovirology. 2009;6:49. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant RM. Hecht FM. Warmerdam M, et al. Time trends in primary HIV-1 drug resistance among recently infected persons. JAMA. 2002;288:181–188. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masquelier B. Bhaskaran K. Pillay D, et al. CASCADE Collaboration. Prevalence of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance and the role of resistance algorithms: Data from seroconverters in the CASCADE collaboration from 1987 to 2003. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:505–511. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000186361.42834.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bracciale L. Colafigli M. Zazzi M, et al. Prevalence of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance in HIV-1-infected patients in Italy: Evolution over 12 years and predictors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:607–615. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.UK Collaborative Group on HIV Drug Resistance: UK Collaborative HIV Cohort Study. UK Register of HIV seroconverters: Evidence of a decline in transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance in the United Kingdom. AIDS. 2007;21:1035–1039. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280b07761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yerly S. von Wyl V. Ledergerber B, et al. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Transmission of HIV-1 drug resistance in Switzerland: A 10-year molecular epidemiology survey. AIDS. 2007;21:2223–2229. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f0b685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]