Abstract

Introduction

The liability crisis may affect residency graduates' practice decisions, yet structured liability education during residency is still inadequate. The objective of this study was to determine the influence of medical liability on practice decisions and to evaluate the adequacy of current medical liability curricula.

Methods

All fourth-year residents (n = 1274) in 264 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited allopathic and 25 osteopathic US obstetrics and gynecology residency training programs were asked to participate in a survey about postgraduate plans and formal education during residency regarding liability issues in 2006. Programs were identified by the Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology directory and the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists residency program registry. Outcome measures were the reported influence of liability/malpractice concerns on postresidency practice decision making and the incidence of formal education in liability/malpractice issues during residency.

Results

A total of 506 of 1274 respondents (39.7%) returned surveys. Women were more likely than men to report “region of the country” (P = .02) and “paid malpractice insurance as a salaried employee” (P = .03) as a major influence. Of the respondents, 123 (24.3%) planned fellowship training, and 229 (45.3%) were considering limiting practice. More than 20% had been named in a lawsuit. Respondents cited Pennsylvania, Florida, and New York as locations to avoid. In response to questions about medical liability education, 54.3% reported formal education on risk management, and 65.2% indicated they had not received training on “next steps” after a lawsuit.

Discussion

Residents identify liability-related issues as major influences when making choices about practice after training. Structured education on matters of medical liability during residency is still inadequate.

Editor's Notes: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument (1.6MB, pdf) used in this study.

What was known

The liability crisis may affect residency graduates' practice decisions, particularly in specialties with high liability exposure, such as obstetrics-gynecology.

What is new

Nearly a quarter of fourth-year obstetrics-gynecology residents planned fellowship training, and nearly one-half considered limiting their practice, potentially due to liability concerns. Although 20% of respondents had already been named in a lawsuit, many programs did not offer education on medical liability.

Limitations

Survey research, 39.7% response rate.

Bottom line

Residents reported that liability-related issues significantly influence their decisions about posttraining practice.

Introduction

Concerns about medical malpractice and the medical liability crisis are not new. Their impact on the field of obstetrics and gynecology has been discussed since the 1970s and 1980s.1 Evaluations of the specific bearing of the liability crisis on obstetricians and gynecologists have demonstrated regional influence on providers.2,3 Nationally, more than 60% of obstetricians and gynecologists have made one or more changes to their practices as a result of the affordability or availability (or both) of professional liability insurance or because of the perceived risk or fear of professional liability claims or litigation.4

To date, few studies have investigated the influence of the liability crisis on the decision patterns of residents. Mello and Kelly5 surveyed Pennsylvania residency program directors and senior residents in anesthesiology, general surgery, emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, orthopedics, and radiology to assess the effect of the liability crisis on practice decisions. Obstetrics and gynecology residents were least represented (11%) in this study, yet obstetrics and gynecology residents were most likely to cite malpractice costs as a strong influence on choice of practice location. Among those obstetrics and gynecology residents who planned to leave their state of training, more than 65% cited malpractice costs as the primary reason. Becker et al6 reported that 35% of obstetrics and gynecology residents surveyed (including residents in all 4 years of training) reported they were pursuing fellowship or a practice limited solely to gynecology because of concerns about malpractice.

This study was prompted by concern about the impact of the liability crisis on residents and their outlook on the future of the specialty of obstetrics and gynecology and, ultimately, the accessibility and availability of specialty care for women as a result of an unfavorable liability environment. We sought to determine the influence of medical liability concerns on practice decisions and to evaluate the adequacy of current medical liability curricula in obstetrics and gynecology residency training.

Methods

Survey Design and Distribution

The study was undertaken by the Junior Fellow College Advisory Council (JFCAC) of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). The questionnaire was developed by a subcommittee of the ACOG JFCAC, with the aim of collecting demographic data and the perceptions of graduating fourth-year obstetrics and gynecology residents on the liability crisis and its impact on practice decisions. The questionnaire underwent extensive review and modification by the entire 23 members of the ACOG JFCAC to ensure construct, content, linguistic, and internal validity. The survey tool was validated through pilot testing with a selected group of residents in training (not fourth-year residents), and the final questionnaire was approved by the entire 2005–2006 ACOG JFCAC before distribution.

The survey was mailed in March 2006 to all fourth-year residents (n = 1274) in 264 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited allopathic and 25 osteopathic US training programs in obstetrics and gynecology residency. Residency programs were identified by the Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology (CREOG) directory and the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists residency program registries. Surveys were sent to each program's residency director and coordinator, with a cover letter requesting that the surveys be distributed to all fourth-year residents in the program. Reminders/requests for participation were announced at the 2006 CREOG and APGO Annual Meeting, through the American Residency Coordinators in Obstetrics and Gynecology listserv, and via correspondence by the ACOG JFCAC members to their respective Junior Fellow District Advisory Councils. The aim was to survey fourth-year residents during the narrow window of opportunity during which they were making practice decisions (the latter half of their final year of training). To maintain confidentiality, individual respondents were not tracked. Completed surveys were returned by mail or fax to the ACOG Office of Junior Fellow Activities, in Washington, DC. An exemption was granted by the ACOG Institutional Review Board.

Survey Content

Residents were queried regarding their plans to pursue postresidency training, type of posttraining practice setting, plans to limit type and scope of postresidency practice due to liability concerns, and whether they had been named in a medicolegal lawsuit related to the practice of obstetrics and gynecology during residency. Survey respondents identified states being considered for postresidency employment in obstetrics and gynecology, as well as those states in which residents planned to avoid practicing due to liability concerns. On a 5-point scale (5 = major influence, 3 = minor influence, 1 = no influence), residents were asked to rate factors influencing their choice of posttraining practice setting (specific institution, location, income potential, liability parameters, teaching opportunity, proximity to family). The survey also inquired about the role medical liability played when first deciding to pursue training in obstetrics and gynecology and, subsequently, when deciding on type of postresidency practice. Additionally, residents were asked about their experiences regarding formal training and education on medical liability issues during residency and whether they had been given advice to avoid practice in their current geographic location.

Statistics

As we were not able to specifically track nonresponders, we used the national ACOG database as our “control” to assess demographics of those who did respond as compared to those in the known national database of ACOG residents. Although the national database is/was not limited to fourth-year residents, the demographics were thought to be representative of the surveyed group. Demographic characteristics of the survey population were described using ranges, means, and percentages. Questions using a 5-point scale were reported with means and standard deviations. Student t test and χ2 analyses were performed to evaluate effects of age and sex on factors noted to influence practice decisions and the effects of curriculum and advice on subsequent plans to limit practice. All other questions were described using percentages.

Results

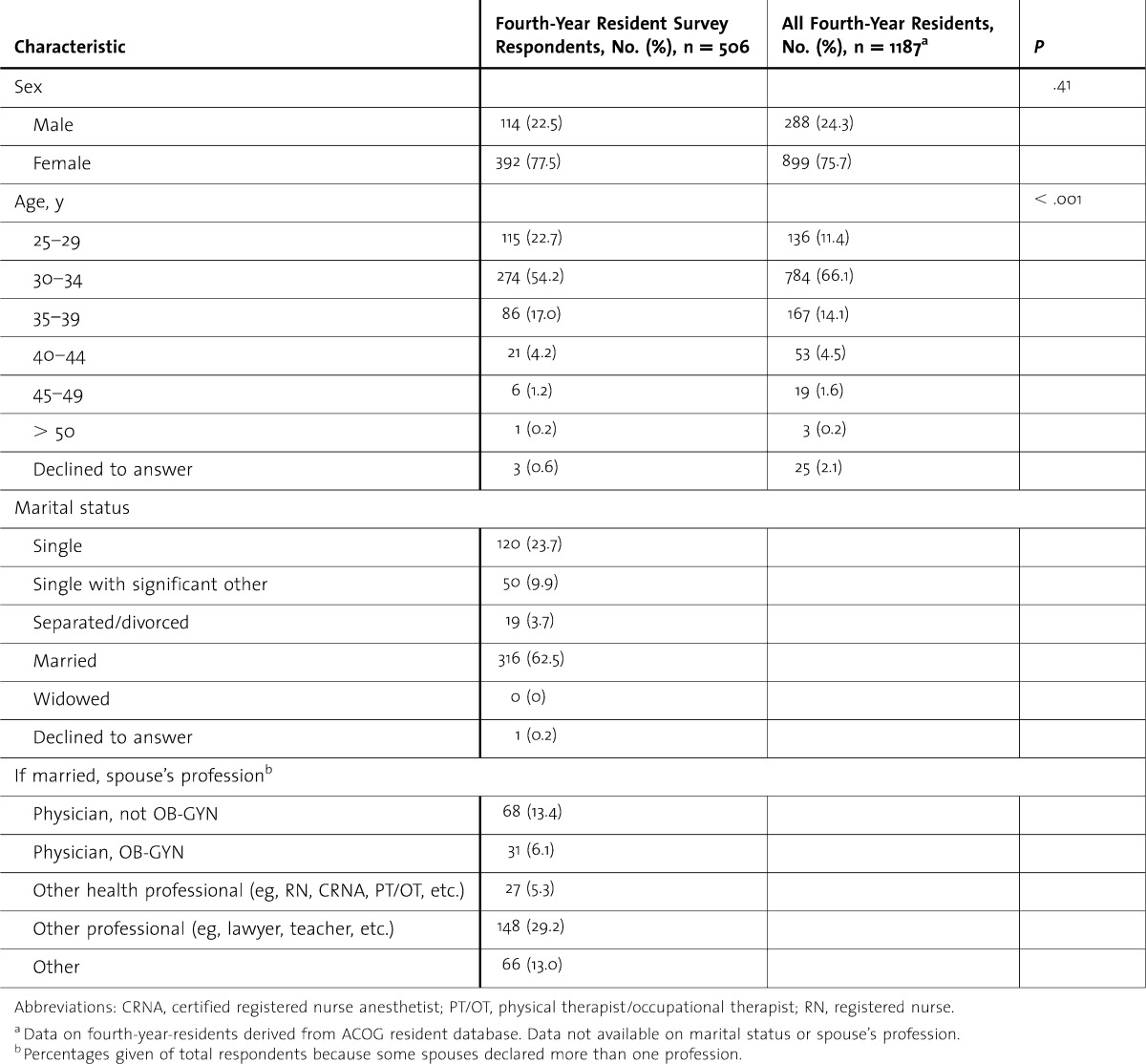

A total of 506 fourth-year residents (39.7%) returned surveys. There was no difference in distribution of respondents and the distribution of fourth-year residents in the 2006 ACOG's membership database (table 1). There was a significant difference in the age of survey participants as compared with the general fourth-year resident population (P < .001), with a greater proportion of respondents in the youngest (25–29 years) age group. Nearly half (48.2%) of respondents were in training programs in the states of New York, California, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, and most (91.3%) were receiving training in an urban setting, whether university or community based. A large portion (70.2%) were planning to pursue practice directly; 24.3% were planning to pursue postresidency training (subspecialty fellowship), and 5.5% were undecided.

TABLE 1.

Fourth-Year Obstetrics-Gynecology Resident Characteristics: Survey Respondents Versus Entire Cohort

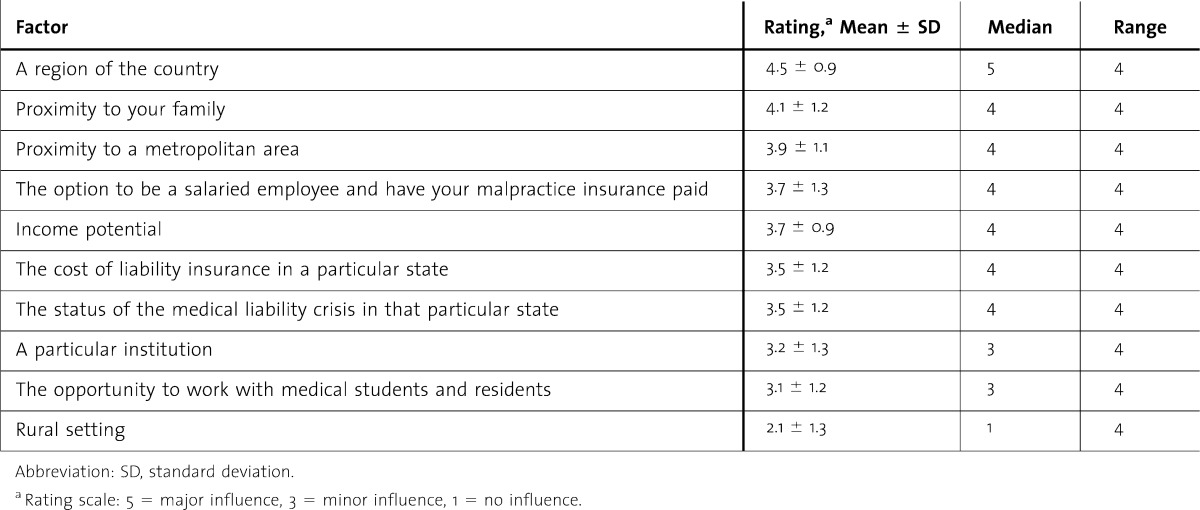

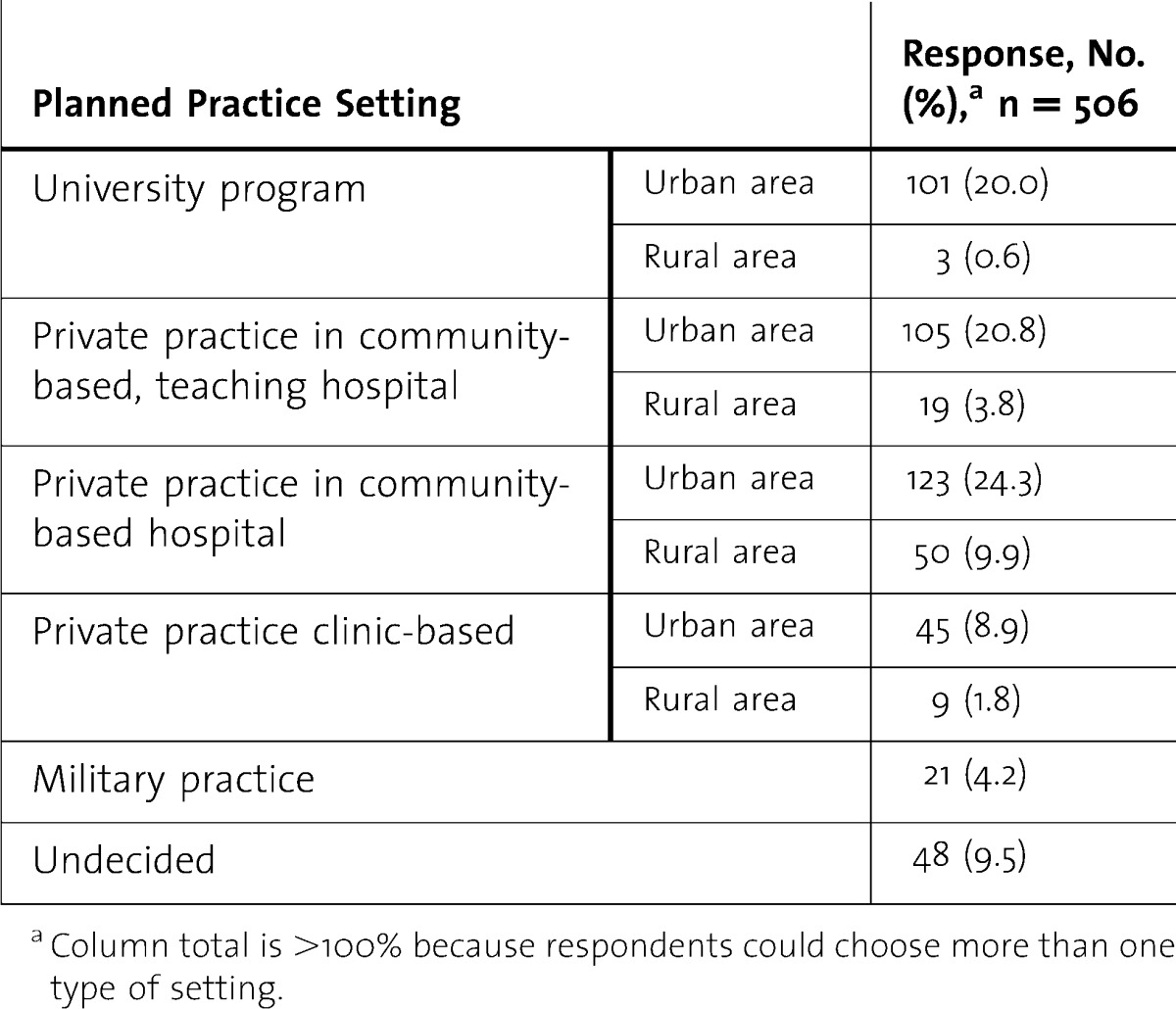

Using a 5-point scale (5 = major influence, 3 = minor influence, 1 = no influence), residents rated the extent that medical liability was an issue at the time of deciding to pursue residency training in obstetrics and gynecology (2.34 ± 1.16) and currently, when deciding on the type of postresidency practice (3.13 ± 1.45). Respondents commonly planned to practice in an urban area (65.1%) after completion of training (table 2). The factors with the reported greatest influence on choice of posttraining practice were the region of the country, proximity to family, liability concerns, and income issues (table 3). Paid malpractice insurance as a salaried employee was viewed as more important than income potential. Subgroup analysis by sex revealed female respondents were more likely than males to say that “region of the country” (P = .02) and “paid malpractice insurance as a salaried employee” (P = .03) were major influences. Male residents surveyed were more likely to say that “rural setting” was a major influence (P = .009).

TABLE 2.

Respondent's Reported Planned Practice Setting After Completion of Training

TABLE 3.

Respondent's Rated Importance of the Practice Factors on Practice Choice After Training

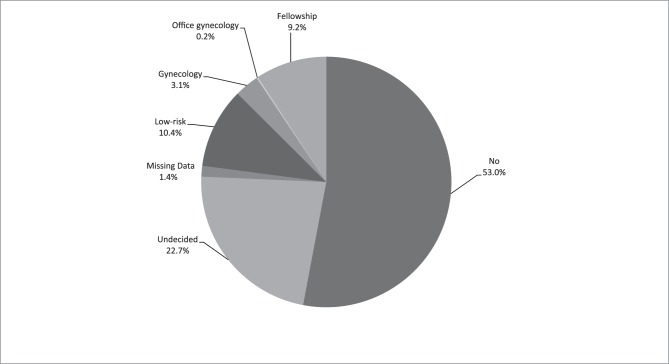

When asked about plans to limit type and scope of practice because of the current medicolegal liability environment, 229 (45.3%) residents responded “Yes” or “Undecided,” with plans for limiting practice to low-risk obstetrics and gynecology being most frequently stated (figure). Specifically identifying “based on medical liability concerns,” residents were surveyed regarding states they were avoiding for postresidency practice in obstetrics and gynecology. Pennsylvania (12.6%) and Florida (8.7%) were the 2 most frequently identified, followed by New York (3.6%), Nevada (3.4%), and West Virginia (3.2%), all Red Alert liability “crisis”7 states. Additionally, one-third (34.2%) of respondents had been “warned or advised” not to practice in their current location (most commonly Ohio [13.9%], Pennsylvania [13.9%], and New York [11.0%]), with “medical liability concerns” (85.5%) most frequently cited as the reason. Whether residents were “warned” had no effect on their plans to limit practice (P = .34).

FIGURE.

Plans to Limit Practice—Participants Responded to the Following Question: Are You Planning on Limiting the Type and Scope of Your Practice Due to the Current Medicolegal Liability Environment? If Yes, How?

In response to questions about litigation experience, 20.7% of residents reported that they had been named in a lawsuit related to events during training. Of those who were named, 83.1% of cases were still ongoing. In response to the question asking whether they had received formal education regarding medical liability risk management during training, more than half (54.3%) responded “Yes,” but a greater number of respondents (65.2%) reported that they had never received any formal training regarding “next steps” once named in a lawsuit. Formal training in medical liability issues had no effect on plans to limit practice (P = .05).

Discussion

Residents identify liability-related issues as major influences when making choices about posttraining practice. Structured education on matters of medical liability during residency is still inadequate.

Our study is unique in that it focused specifically on residents presently in training in obstetrics and gynecology, arguably one of the specialties most conspicuously affected by the medical liability crisis. Furthermore, there was broad geographic representation among the respondents, including residents from 39 states, military training, and the District of Columbia, as compared with previous evaluation of residents from multiple specialties located in just one state.5

According to the 2003 Socioeconomic Survey of ACOG Fellows8 “Profile of Ob-Gyn Practice,” 18% of respondents identified themselves as subspecialists. In comparison, 24.3% of survey respondents planned to pursue postresidency subspecialty fellowship training. The current survey respondents were divided on the issue of plans to limit practice based on liability concerns. However, the percentage of respondents who reported they considered limiting practice immediately upon completing residency (45.3% responding either “yes” or “undecided”) is surprising; one might have predicted that residents newly completing training would have been less willing to restrict their practice at the outset. Nevertheless, this may be reflective of caution, bred by the new culture of training under a system of relatively constant supervision and limited autonomy of the resident, or of pragmatism, when observing the negative liability climate. Today's residents are savvy to the realities of the current liability crisis and are aware of the state-to-state variations in the liability environment, as evidenced by their reports of avoiding practice in certain states based on medical liability concerns. Neither factors of formal training in medical liability issues nor warnings to avoid practice in a given state had significant effects on plans to limit practice. It is uncertain whether this lack of effect was because of the inadequacy of widespread formal education (54.3% received formal education on liability during residency) or because of warnings primarily to avoid practice in a particular location (compared with warnings to limit practice). Geography and proximity to family were most important in choice of practice, but the stability of income as provided by a salaried position, particularly with liability insurance paid by an employer, was more important than potential income. These ratings may reflect a shift in priorities of today's young physician, whether because of generational predilections toward protected personal (nonworking) time or because of risk aversion and lower expectations for lucrative compensation.

Respondents in our study demonstrated that 1 in 5 obstetrics and gynecology residents are graduating with the experience of already having been involved in a lawsuit. There has been limited data published previously regarding the rate at which residents are named in lawsuits. This is compounded by residents often being named then dropped, but the stress and trauma of being named in the first place are not erased when the resident is no longer a named defendant. Claims reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank between 1991 and 2003 involved residents (or fellows) as defendants in less than 1% of cases. However, claims reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank are specific to those where payment was made9 and do not reflect the frequency at which residents are initially named in lawsuits, particularly in the teaching hospital setting. Previous reports indicate that, according to one large malpractice insurer's experience in the graduate medical education setting in the northeastern United States, resident physicians were named in 22% of claims between 1994 and 2003.10

Our study has several limitations. First, our survey response rate was only 39.7%. Although this is an incomplete sampling, the characteristics of the survey respondents are consistent with the overall population of fourth-year residents and the generalizability of our study results should be relatively robust. Second, the study data presented is from 2006, and 5 years have elapsed since the study was conducted. We do not believe that there has been significant change in tort reform nationally or in most states since 2006, particularly in the states highlighted to be of concern by survey respondents. Further, liability concerns remain a top national issue for obstetrician-gynecologists, and thus, the overall impact on postresidency decisions for training and practice are not likely to have changed significantly.

Conclusions

Graduating residents in obstetrics and gynecology identify liability “crisis” states (ie, Pennsylvania, Florida, New York, Nevada, and West Virginia) as places to avoid for postresidency practice. More than 20% of residents have already been named as a defendant while still in training, but less than half of respondents reported ever receiving formal education regarding medical liability risk management or “next steps” after being named in a lawsuit, underscoring a deficiency in resident education curricula.

Footnotes

May Hsieh Blanchard, MD, is Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Ob-Gyn Residency Program Director at the University of Maryland; Patrick S. Ramsey, MD, MSPH, is Adjunct Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and the School of Public Health at University of Texas; Rajiv B. Gala, MD, is a Clinical Instructor and Ob-Gyn Residency Program Director at Ochsner Medical Center; Cynthia Gyamfi- Bannerman, MD, is Associate Clinical Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Columbia UniversityMedical Center; Sindhu K. Srinivas, MD, is Assistant Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania; Armando E. Hernandez-Rey, MD, is Associate Director of the Fertility and IVF Center of Miami.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Presented in part at the 2007 CREOG and APGO Annual Meeting, in Salt Lake City, UT, on March 7–10, 2007.

The authors wish to recognize Mary Behneman, BS, Ms Christine Himes, and LaShawn Jordan, BS, for administrative assistance in the production, tracking, and collection of the surveys. Special thanks to Andrea M. Carpentieri, MA, for assistance in data collection and analysis, and to Sterling Williams, MD, MS, for aid in the creation and conceptual development of the project. Mss Behneman, Himes, Jordan, and Carpentieri and Dr Williams receive no compensation for their contributions.

References

- 1.Rosenblatt RA, Hurst A. An analysis of closed obstetric malpractice claims. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74(5):710–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedetti TJ, Baldwin LM, Skillman SM, Andrilla CH, Bowditch E, Carr KC, et al. Professional liability issues and practice patterns of obstetric providers in Washington State. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1238–1246. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000218721.83011.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donlen J, Puro JS. The impact of the medical malpractice crisis on OB-GYNs and patients in southern New Jersey. N J Med. 2003;100(9):12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson NS, Strunk AL. Overview of the 2006 ACOG survey on professional liability. ACOG Clin Rev. 2007;12(2):1, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mello MM, Kelly CN. Effects of a professional liability crisis on residents' practice decisions. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(6):1287–1295. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000163255.56004.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.[ACOG] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG mobilizes women to support medical liability legislative reform. ACOG Today. 2003;47:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.[ACOG] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2003 Economic Survey Results. http://www.acog.org. Accessed March 4, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Practitioner Data Bank. Public Use Data File. http://www.npdbhipdb.com/npdb.html. Accessed June 26, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051–1056. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]