Abstract

Trichotillomania (TTM) is an impulse-control disorder, in which patients chronically pull hair from the scalp and/or other sites. We herein report a 8-year-old male patient who developed TTM in the classical tonsure pattern ("Friar Tuck" sign). The diagnosis was confirmed by trichoscopy, which showed decreased hair density, broken hairs with different shaft lengths, black dots, signs of hemorrhage, and an absence of exclamation mark hairs.

Keywords: alopecia, dermoscopy, Friar Tuck sign, trichotillomania, trichoscopy

Case

An otherwise healthy 8-year-old boy presented with a 3-month history of bald patch on the scalp nonresponsive to empiric treatment with oral and topical antifungals. The child was living with his grandmother while his parents, immigrants in another country, had a conflicting relationship and were divorcing. At physical examination, a well-defined round patch of scarce hair was observed on the vertex. The hair covering this area presented differing lengths, some with blunt ends (broken hairs), and some with tapered ends (new growth). Eyelashes and eyebrows were uninvolved. Scalp dermoscopy revealed decreased hair density, broken hairs with different shaft lengths, short vellus hairs, black dots, signs of recent hemorrhage, and absence of exclamation mark hairs. The clinico-dermoscopic aspect, together with the psycho-familial background, suggested the diagnosis of trichotillomania. When confronted with the possibility of self-inflicted injury, the patient claimed responsibility for the habit of hair pulling when he was alone "thinking in things". He was referred for a child psychiatrist, for cognitive-behavioral intervention.

Figure 1.

(A) Round patch of incomplete alopecia on the vertex demonstrating the "tonsure pattern" or "Friar Tuck sign". No inflammation or scale was present on examination. (B) Detail of the alopecic area.

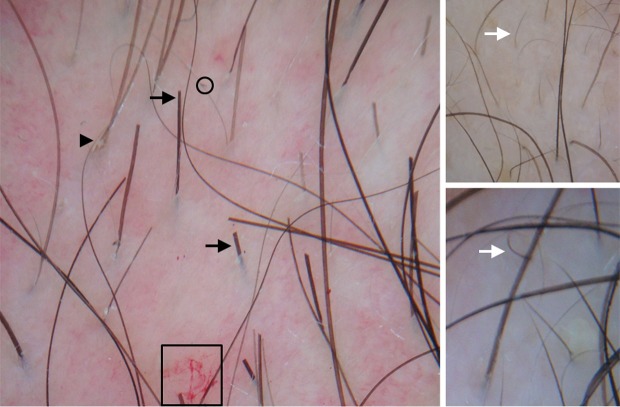

Figure 2.

Trichoscopy showing decreased hair density, broken hairs with different shaft lengths (black arrows), short vellus hairs (white arrows), black dots (circle), signs of hemorrhage (square box), and an absence of exclamation mark hairs. Note a recently fractured hair (arrow head).

Trichotillomania (TTM), or trichotillosis, is classified as an impulsecontrol disorder according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).[1] Although TTM was previously thought to be an uncommon condition, it is now believed to occur more frequently (1-4% of general population). It occurs in adult females (3.4%) more often than in adult males (1.5%).[2] Among children, both genders seem to be affected equally. The most common age of onset is in preadolescents to young adults. Young children often have a selflimited course of hair pulling. Stressful situations such as a new sibling, sibling rivalry, lack of parental affection, or infections may precede the onset of the disease in this age group.[3] In our patient, the divorce of parents, their conflicting relationship and the lack of their presence may have been the trigger factors. Adults frequently have associated psychiatric conditions and the course of TTM may be chronic or episodic. The diagnostic criteria for TTM are: (A) recurrent pulling out of one's hair, resulting in noticeable hair loss, (B) an increasing sense of tension immediately before pulling out the hair or when attempting to resist the behavior, (C) pleasure, gratification, or relief when pulling out the hair, (D) the disturbance is not better accounted for by another mental disorder and is not due to a general medical condition, and (E) the disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.[1]

Hair pulling can occur on any part of the body where hair grows, namely the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, axillary, body, and pubic area. The general morphology of an individual lesion showing a geometrical shape and incomplete nonscarring alopecia with broken-off hairs of varying lengths is typical of TTM. A common location for pulling hair is the crown of the head, leading some patients to develop a tonsure pattern, also referred to as the "Friar Tuck" sign.[3] Differentiation from other forms of hair loss, including alopecia areata (AA), androgenetic alopecia and tinea capitis, is crucial because treatment of TTM is quite different. Scalp and hair dermoscopy (trichoscopy) improves diagnostic accuracy beyond simple clinical inspection. It represents a useful tool for differentiating between TTM and other types of alopecia, especially patchy AA, thus avoiding scalp biopsy, which is particularly important in the case of children.[4]

Therapeutic approach to TTM is based on the age of onset. Treatment options include conservative attitude, especially in pre-school age children, cognitive-behavioral therapy (including habit reversal training), and psychopharmacological interventions (tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and others).[3,5]

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson GA, Pyle RL, Mitchell JE. Estimated lifetime prevalence of trichotillomania in college students. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:415–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah DE, Koo J, Price VH. Trichotillomania. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham LS, Torres FN, Azulay-Abulafia L. Dermoscopic clues to distinguish trichotillomania from patchy alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:723–726. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin ME, Zagrabbe K, Benavides KL. Trichotillomania and its treatment: a review and recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:1165–1174. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]