Abstract

Morphinans are a class of compounds containing the basic structure of morphine. It is well-known that morphinans possess diverse pharmacological effects on the central nervous system. This review will demonstrate novel neuroprotective effects of several morphinans such as, dextromethorphan, its analogs and naloxone on the models of multiple neurodegenerative disease by modulating glial activation associated with the production of a host of proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors, although dextromethorphan possesses neuropsycotoxic potentials. The neuroprotective effects and the therapeutic potential for the treatment of excitotoxic and inflammatory neurodegenerative diseases, and underlying mechanism of morphinans are discussed.

Keywords: Dextromethorphan and its analogs, Naloxone, Neuroprotective effects, Neuropsychotoxicity

INTRODUCTION

Morphinan derivatives, which include dextromethorphan (DM; 3-methoxy-17-methylmorphinan), its analogs and naloxone, belong to a chemical class related to the opiates. Accumulating evidence suggests that morphinans may play a role in neuronal modulation. DM is a common ingredient in more than 125 cough and cold remedies. Patented by Hoffmann-La Roche in 1954 as an antitussive agent, DM has strong safety and efficacy profiles with no sedative or addictive properties at the recommended doses (Bem and Peck, 1992). A potential advantage of DM is its lack of gastrointestinal side effects, such as constipation, and it causes less central nervous system (CNS) depression than opioids when used as antitussives at usual doses. In the past decade, investigators have documented that DM has an NMDA receptor antagonistic effect with neuroprotection. However, the DM dose for the neuroprotective effect is much higher than the cough suppressant dosage. Clinically, high doses of DM can produce psychotropic effects (Wolfe and Caravati, 1995; Desai et al., 2006). Furthermore, DM has been recognized as the object of drug-seeking behaviour in several countries (Cranston and Yoast, 1999; Chung et al., 2004). That hampers the development of DM as a useful neuroprotective agent. We will discuss DM analogs (incuding DM metabolites) with improved safety profiles in this review.

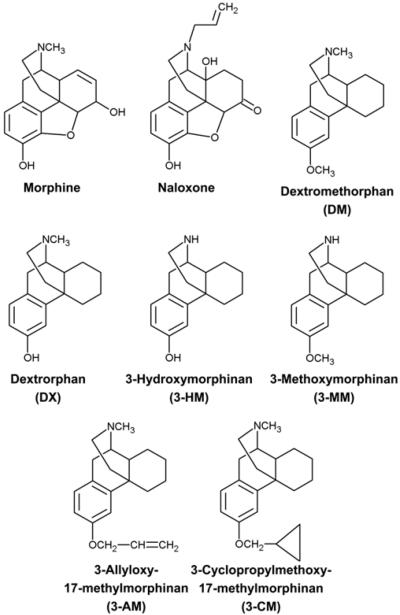

Endogenous opioid peptides are widely distributed in the central nervous system (CNS) and are important in regulating the development of neural cells (Knapp et al., 1998). They interact with related yet distinct G-protein coupled receptors to exert their physiological effects, including nociceptive/analgesic effects, respiration, ionic channel activity, and immune responses (Satoh and Minami, 1995; Roy and Loh, 1996). So far, at least three types of opioid receptors (μ, δ, and κ) have been identified (Satoh and Minami, 1995). Another morphinan, naloxone, in particular the (-)-stereoisomer, is a stereospecific yet non-selective antagonist of the three classical opioid receptors (Chien and VanWinkle, 1996). Accumulating evidence suggests that naloxone, which shares a basic opiate-like structure with DM, might also have neuroprotective effects in an opiate receptor-independent fashion (Chatterjie et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2002; Qin et al., 2005). Thus, studies have demonstrated that DM and its analogs are neuroprotective against neurodegeneration or inflammtion, at least in part through a mechanism similar to that of naloxone. The present review is designed to extend earlier understanding of negative and positive effects caused by DM or DM analogs (including DM metabolites), and to discuss the neuroprotective potential of naloxone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Structures of morphine, naloxone, dextromethorphan (DM), and DM analogs

METABOLIC PATHWAY OF DM

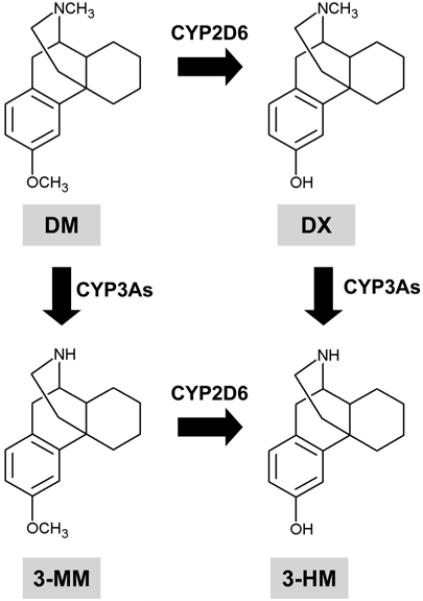

DM is metabolized primarily to dextrorphan (DX) by O-demethylation, and to a lesser extent to 3-methoxymorphinan (3-MM) by N-demethylation. Both meta-bolites are further demethylated to 3-hydroxymor phinan (3-HM) (Fig. 2). Urinary recovery studies in humans and rats indicate that DX and 3-HM are excreted largely (>95%) as glucuronide conjugates. The pharmacology of 3-MM is not significant, and it does not have major behavioral side effects. We have observed that 3-HM has antiparkinsonian effects with behavioral safety. The major metabolite, DX, has neuro-protective potential (Tortella et al., 1989b). DX has a lower affinity than DM at the [3H]DM binding site (Craviso and Musacchio, 1983), but has a higher affinity than DM at the phencyclidine (PCP) receptor (Murray and Leid, 1984) and produces PCP-like discriminative stimulus effects (Holtzman, 1980). The extent of the metabolic conversion of DM to DX is highly dependent on the route of administration (Wu et al., 1995). That is, considerable DX is formed when DM is administered intraperitoneally (i.p.), whereby it is absorbed into the hepatic portal circulation, while less DX may be formed when DM is administered subcutaneously (s.c.). However, Holtzman (1994) reported that DM (30 mg/kg, s.c.) has PCP-like discriminative effects of its own that are independent of conversion to DX. These are most easily appreciated in vitro when metabolism is not an important issue. In addition, ample evidence indicates that DM has effects of its own that are independent of its conversion to DX. Interestingly, DM (Holtzman, 1994) and DX (Holtzman, 1980) substituted completely for PCP in rats trained to distinguish PCP from saline, and DM also substituted for DX in pigeons trained to discriminate DX from saline (Herling et al., 1983). Therefore, the route of administration is an important determinant in the deposition of DM and its metabolites, as well as in its behavioral effects. Other factors should also be considered in any behavioral studies of DM, such as dosage, time of testing, and capacity for glucuronidation.

Fig. 2.

Metabolic pathway of DM. CYP = cytochrome P450

NEUROPROTECTION PROVIDED BY DM

Effects of DM on convulsive behaviours

DM has been reported to possess anticonvulsant activity against seizures induced by maximal electroshock (Tortella and Musacchio, 1986; Kim et al., 2003b), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) (Ferkany et al., 1988; Leander, 1989), sound (Chapman and Meldrum, 1989), amygdala kindling (Feeser et al., 1988; Takazawa et al., 1990), kainic acid (KA) (Kim et al., 1996, 1997b), BAY k-8644 (Kim et al., 2001b; Shin et al., 2004) and trimethyltin (Shin et al., 2007). Like DM, its meta-bolite DX (the dextrorotatory form of levorphanol), is reported to exert anticonvulsant activity against seizures induced by maximal electroshock (Kim et al., 2003b), NMDA (Ferkany et al., 1988), sound (Chapman and Meldrum, 1989), and BAY k-8644 (Kim et al., 2001b; Shin et al., 2004). Since in most studies DX was several-fold more potent as an anticonvulsant than DM, it was suggested that the metabolite in vivo significantly contributes to the anticonvulsant activity of the parent drug (Rogawski and Porter, 1990). However, the data indicated that metabolism to DX may not be necessarily required for DM to produce its effects in vivo (Kim et al., 2003a).

The mechanisms of anticonvulsant action of DM and DX remain to be further characterized. Both compounds show high affinity for σ-receptors of the σ1-type, but binding affinity? of DX is 2-5 times lower than that of DM (Quirion et al., 1992), which is not consistent with the greater anticonvulsant activity of DX.

In addition to interacting with σ-receptors, DM was shown to weakly block NMDA receptor-mediated responses (Aram et al., 1989; Kim et al., 1999), which seems to be mediated by binding to a non-competitive antagonist site of the NMDA receptor cation channel (Mendelsohn et al., 1984). Compared to DM, DX is several-fold more potent as an NMDA receptor antagonist (Cole et al., 1989), which is consistent with its higher anticonvulsant effects in vivo.

Feeser et al. (1988) reported that DM decreased seizure intensity in fully kindled rats, and proposed that clinical testing of this drug as an anticonvulsant is warranted, but Takazawa et al. (1990) demonstrated that DM has a narrow therapeutic window as an anticonvulsant on kindled seizures. Furthermore, the active metabolite DX was reported to be ineffective against amygdala-kindled seizures (Le Gal La Salle et al., 1977). Takazawa et al. (1990) also reported that, after 30-50 mg/kg DM, animals developed hindlimb ataxia and sedation in a dose-dependent manner without there being resting EEG changes. The proconvulsant activity of DM may depend on the amimal model used, since Echevarria et al. (1990) showed that DM was an anticonvulsant in the maximal electro-shock test, but was proconvulsant in the flurothyl test in rats.

Leander (1989) has argued that the antitussives have an anticonvulsant action separate from their PCP-like blockade of NMDA receptors. In this respect, another earlier finding that DM and DX, but not MK-801, are capable of potently blocking voltage-gated calcium and sodium inward currents of neurons (Netzer et al., 1993) is of considerable interest, since such effects could explain why the antitussives, but not more selective NMDA receptor antagonists such as MK-801, are anticonvulsants in kindling models. Indeed, it has been suggested that the primary mechanism of action of DM is simply blockade of certain ion channels (Tortella et al., 1989b). In addition to direct effects on voltage-gated cation channels, the binding of DM to σ-receptors could be involved in the anti-convulsant effect of this drug (Tortella et al., 1989b; Quirion et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2003b; Shin et al., 2005, 2007), although the role of this site in anticonvulsant drug actions remains to be determined. Both anticonvulsant and proconvulsant effects have been reported for σ-site ligands (Tortella et al., 1989b).

Radiolabeled DM binds to high affinity sites in the brain which show striking similarities in binding characteristics and regional distribution to σ-binding sites and are modulated by the antiepileptic drug phenytion (Tortella et al., 1989b; Rogawski and Porter, 1990). Indeed, at least one of the high-affinity binding sites of DM is identical to the σ-1 site (Zhou and Musacchio, 1991). Autoradiographic studies have shown that high-afifnity DM binding sites are different from the high-affinity DX site that is associated with the activated state of the NMDA receptor cation channel complex (Franklin and Murray, 1990). DX has a low affinity for DM binding sites in the brain, whereas DX is 8-fold more potent than DM in inhibiting [3H]DX binding (Franklin and Murray, 1990), which is consistent with its higher potency as an NMDA receptor antagonist. With respect to the high affinity DM (presumably σ1) site, in addition to σ1-site ligands, a variety of calcium channel antagonists compete for this site (Tortella et al., 1989b), raising the possibility of a relationship between DM and voltage-gated ion channels.

The fact that DM and DX exert biphasic effects on neural excitation as exemplified by their anticonvulsant and pro-convulsant effects seen in the same convulsive animals, predicts that these drugs, if they have any effect at all, will have only a narrow therapeutic window in epileptic patients. Earlier studies suggest that epileptogenesis renders the brain more susceptible to the PCP-like adverse effects of NMDA receptor antagonists (Loscher and Honack, 1991; Dziki et al., 1992). Many findings are not compatible with the idea that DM is just a prodrug for DX. Rather, they strongly indicate that the parent drug is primarily responsible for the anticonvulsant effects observed in vivo, at least in kindling and KA models.

Previous findings have demonstrated that DM prevents seizures, mortality and hippocampal cell loss in a dose-dependent manner. One interpretation for the neuroprotective effects of DM through its anticonvulsant effect is that it reduces the excitotoxicity exerted on the neurons by glutamate through the inhibition of NMDA receptors (Choi, 1987). DM has also been shown to attenuate kainic acid (KA)-induced increases in AP-1 binding activity and C-Jun/Fos-related antigen (FRA) expression in the hippocampus, collectively suggesting that DM is an effective antagonist of KA and a potent protectant for convulsants (Kim et al., 1996, 1999).

Effects of DM on the cerebral ischemia

It was shown in several in vivo models of ischemic brain injury that treatment with DM could protect the brain against infarction and related pathophysiological and functional consequences of ischemic injury (George et al., 1988; Tortella et al., 1989a). In addition, several in vitro (Klette et al., 1995) and in vivo studies (Britton et al., 1997; Tortella et al., 1999) have confirmed the neuroprotective actions of DM and have offered critical insights into its possible cellular mechanism of action. In particular, comprehensive studies undertaken with the rodent focal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury model showed the potent ability of DM to decrease the volume of cerebral infarction and improve functional recovery as postinjury therapy (Britton et al., 1997; Tortella et al., 1999).

DM attenuated the loss of vulnerable neuons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in global ischemia models (Bokesch et al., 1994). DM decreased cerebral infarct size in areas of severe neocortical damage after ischemia and reperfusion (Britton et al., 1997). In in vitro hypoxia models, DM reduced neuronal loss and dysfunction, which was manifest in decreased amplitude of the anoxic depolarization (Luhmann and Scheid, 1994). DM also attenuated in vitro degeneration induced by acute glucose deprivation (Monyer and Choi, 1988).

A comparable attenuation of post-ischemic hypoper-fusion was found with DM in incomplete global cerebral ischemia (Tortella et al., 1989a). Furthermore, there was strong evidence of a corrected improvement in brain function, as DM facilitated recovery of the somatosensory evoked potential (Steinberg et al., 1991) and attenuated EEG dysfunction in these and other ischemia studies (Tortella et al., 1989a). This is consistent with findings of improved neurologic function in focal ischemia (Tortella et al., 1999).

DM attenuates dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by MPTP

An earlier report demonstrated that DM showed significant protective effects in response to dopaminergic toxicity induced by MPTP in mice, in which the underlying mechanisms for the neuroprotective activity of DM were also investigated using wild-type and NADPH oxidase-deficient mice (Zhang et al., 2004). They found that wild-type mice that received daily MPTP injections showed significant loss of DA neurons in the subtantia nigra pars compacta. However, the MPTP-elicited neuronal loss was significantly attenuated in those mice receiving DM (Zhang et al., 2004).

NADPH oxidase is the primary enzyme producing extracellular superoxide in microglia, and it was proposed that NADPH oxidase may contribute to MPTP-induced neurotoxicity (Gao et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004). It was observed that NADPH oxidase-deficient mice exhibited significant resistance to MPTP-induced DA toxicity compared to wild-type mice. In addition, the neuroprotective effect of DM was only observed in wild-type mice, but not in NADPH oxidase-deficient mice, suggesting that NADPH-oxidase is a critical target mediating DM’s neuroprotective activity in the MPTP in vivo model.

Gao et al. (2003) have reported that reactive micro-gliosis is associated with MPTP-induced DA neurode-generation, and they further proposed that inhibition of reactive microgliosis underlies DM’s neuroprotective effect against MPTP toxicity. The initial damage of dead neurons elicited by MPTP induces reactive microgliosis, which in turn activates NADPH oxidase through the translocation of cytosolic subunits to the cell membrane and generation of superoxide in wild-type mice. The neuroprotective effect of DM is attributed to its blockade of reactive microgliosis induced by DA neuronal death through the inhibition of both extracellular superoxide and intracellular reactive oxygen species (iROS) (Zhang et al., 2004). However, in NADPH-deficient mice, reactive microgliosis fails to occur because of the lack of a gp91 membrane-binding subunit, and hence DM can not exert its neuroprotective action.

BEHAVIOURAL SIDE EFFECTS AND NEUROTOXICITY INDUCED BY DM

Complex effects of DM on animal behaviours

Based on studies in animals, it has been demonstrated that most symptoms observed in abusers of DM are caused by the major metabolite dextrorphan (DX), which binds to the same central nervous system receptors as PCP. In mice, prolonged exposure to an oral neuroprotective dose of DM produces behavioral suppression followed by behavioral tolerance. Prenatal exposure to DM produces hyperlocomotor activity in the offspring of mice. When these offspring receive additional DM, they demonstrate marked behavioral depression (Kim and Jhoo, 1995). Mice exposed to prolonged oral DM show impaired B cell function and natural killer cell cytotoxicity, which is similar to the immunosuppressive effects of PCP (Kim et al., 1995).

DM alters the behavioral response induced by several drugs of abuse, including morphine, methampheta-mine, and cocaine. DM (25 mg/kg, i.p.) decreases meth-amphetamine self-administration in rats, but does not affect the response to a food reward (Glick et al., 2001). In addition, the coadministration of DM (20 mg/kg, i.p.) with methamphetamine (2 mg/kg, i.p.) attenuates methamphetamine-induced psychological dependence [conditioned place preference (CPP)] and behavioral sensitization (Yang et al., 2006). Pretreatment with DM (20 mg/kg s.c.) potentiates the effects of acute morphine, while it attenuates the effects of chronic morphine on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Glick et al., 2001; Steinmiller et al., 2003).

Pulvirenti et al. (1997) demonstrated that DM (25 mg/kg, i.p.) reduces cocaine self-administration at various doses (0.12, 0.25, and 0.5 mg/kg/2 h infusion) in rats, which is in line with other findings (Kim et al., 1997a). However, Kim et al. (1997a) first reported that DM (40 mg/kg, p.o.) increases the rate of reinforced responses to lower doses of cocaine (0.06 and 0.03 mg/ kg/infusion). Therefore, DM shifts the dose-response curve for cocaine self-administration to the left, which suggests a sensitized response to the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Consistently, Jhoo et al. (2000) reported that DM (i.p.) has a biphasic effect on cocaine-induced psychological dependence [as evaluated by conditioned place preference (CPP)]. DM decreases the CPP for high doses of cocaine and increases the CPP for low doses (Jhoo et al., 2000). Furthermore, Kim et al. (2001a) found that DM exerts biphasic effects on the locomotor stimulation induced by cocaine, and the locomotor activities parallel the FRA immunoreactivity in the striatal complex of mice. Therefore, the cocaine-induced behavioral response is influenced by pre-exposure to DM, although the responses might be regulated by the route, period, or interval of administration, or by the animal model.

DM neurotoxicity might depend on the route of administration

It has been reported that a single treatment with non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonists such as MK-801, PCP or ketamine causes pathological damage in the posterior cingulate cortex and retrosplenial cortex of the rat brain (Olney et al., 1989), and these chemicals can induce heat shock protein HSP-70, which may play a role in cellular repair and/or protective mechanisms in the same regions (Sharp et al., 1994). Hashimoto et al. (1996) demonstrated that induction of HSP-70 protein in the posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortex of the rat brain was maximum at a DM dose of 75 mg/kg, i.p. In contrast, Carliss et al. (2007) demonstrated that oral administration of high doses of DM does not produce neuropathological changes as shown for other NMDA receptor antagonists, suggesting that there are route-specific effects on the disposition of DM and its metabolites in rat brain. However, according to our pilot study (data not shown), more study is required in the understanding of precise neuropathological mechanisms mediated by high doses of DM.

NEUROPROTECTION PROVIDED BY DM ANALOGS

Effects of DM analogs on convulsive behaviours

New analogs of DM also showed a promising anti-convulsant effect (Kim et al., 2001c, 2003b; Zapata et al., 2003). Kim et al. (2003b) investigated the effect of a series of synthesized DM analogs (that were modified in positions 3 and 17 of the morphinan ring system) on maximal electroshock convulsions (MES) in mice. They found that DM, DX, 3-allyloxy-17-methylmorphinan (3-AM), and 3-cyclopropylmethoxy-17-methylmorphinan (3-CM) had anticonvulsant effects against MES, while 3-methoxymorphinan (3-MM), and 3-hydroxymorphinan (3-HM) did not show any anticonvulsant effects (Kim et al., 2003b). According to these studies, DM, DX, 3-AM, and 3-CM were high-affinity ligands at σ-1 receptors, while they all had low affinity for σ-2 receptors. DX had relatively higher affinity for the phencyclidine (PCP) sites than DM. In contrast, 3-AM and 3-CM had very low affinities for PCP sites, suggesting that PCP sites are not required for their anticonvulsant actions (Kim et al., 2003b). The above suggests that the new DM analogs are promising anticonvulsants that are devoid of PCP-like behavioral side effects, and their anticonvulsant actions may be, at least in part, mediated via σ-1 receptors (Kim et al., 2003b; Shin et al., 2005, 2008).

Another study indicated that the anticonvulsant effects of the morphinans partially involve the L-type calcium channel (Trube and Netzer, 1994), and that DM is a more potent anticonvulsant than DX in both KA- and BAY k-8644-induced seizure models (Kim et al., 2001b). BAY k-8644 is an L-type Ca2+ channel agonist of the dihydropyridine class, which is recognized as a potent convulsant agent that can also potentiate seizures induced by KA (Kim et al., 2001b). The anticonvulsant effect of DM was reversed by BAY k-8644 in this model. In contrast, BAY k-8644 did not significantly affect the anticonvulsant effect from a higher dose of DM or DX. Furthermore, DM appeared more efficacious than DX in attenuation of KA- and BAY k-8644-induced seizures by decreasing KA-induced AP-1 DNA-binding activity and FRA-immuno-reactivity, as well as reducing neuronal loss in the hippocampus (Kim et al., 2001b).

3-Hydroxymorphinan (HM), a metabolite of DM attenuates dopaminergic toxicity induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or MPTP

Based on structure-activity studies designed to find more potent neuroprotective analogs, 3-HM, a DM metabolite missing methyl groups at the O and N sites, emerged as a novel candidate for the treatment of PD among a series of DM analogs (Zhang et al., 2006). Zhang et al. (2005 and 2006) showed that 3-HM was more potent in neuroprotection against LPS-induced neurotoxicity than its parent compound, DM. It was first found that 3-HM was neuroprotective against LPS-induced DA neurotoxicity and was also neurotrophic to DA neurons in primary mixed mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures (Zhang et al., 2005, 2006). The neurotrophic effect of 3-HM was glia dependent, and 3-HM failed to show any protective effect in neuron-enriched cultures. They subsequently demonstrated that it was the astroglia and not the micro-glia that contributed to the neurotrophic effect of 3-HM. This conclusion was based on reconstitution studies in which we added different percentages of microglia (10-20%) or astroglia (40-50%) back to the neuron-enriched cultures and found that 3-HM was neurotrophic after the addition of astroglia but not microglia (Zhang et al., 2006).

Furthermore, 3-HM-treated astroglia-derived conditioned media exerted a significant neurotrophic effect on DA neurons. It appeared likely that 3-HM caused the release of certain neurotrophic factors (i.e., EGF, GDNF, TGF-β1, TGF-α1 and ADNF) from astroglia, which in turn was responsible for the neurotrophic effect of 3-HM. As may be expected, there is also a considerable glial reaction in the substantia nigra pars compacta in PD that can potentially be protective in addition to the detrimental effect on DA neurons. Glial cells, especially astroglia, protect stressed DA neurons through production of neurotrophic factors that counteract oxidative stress. One potential therapeutic avenue will be to stimulate astroglia to produce these neurotrophic factors to rescue damaged or dying neurons. Furthermore, the identity of the neurotrophic factors (i.e., EGF, GDNF, TGF-β1, TGF-α1 and ADNF) released from astroglia induced by 3-HM was characterized (Zhang et al., 2006).

In addition to the neurotrophic effect, the anti-inflammatory mechanism was also important for the neuroprotective activity of 3-HM because the more microglia that were added back to neuron-enriched cultures, the more pronounced LPS-induced neurotoxi-city became and the more a 3-HM-mediated neuroprotection was the effect observed (Zhang et al., 2006). The anti-inflammatory mechanism of 3-HM was attributed to its inhibition of LPS-induced production of an array of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic factors. Thus, 3-HM provides potent neuroprotection by acting on two different cell targets: a neurotrophic effect mediated by astroglia and an anti-inflammatory effect mediated by inhibition of microglial activation. The higher potency of 3-HM is attributed to its additional neurotrophic effect in addition to the anti-inflammatory mechanism shared by both DM and 3-HM (Zhang et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2008).

Zhang et al. (2006) also found that 3-HM provided neuroprotection in the MPTP model, in both in vivo and in vitro studies. In the in vitro system, using primary mixed mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures, 1-5 μM 3-HM significantly and dose-dependently attenuated, reductions in DA uptake induced by MPTP or its active component MPP+; 1-5 μM 3-HM alone resulted in a significantly higher capacity for DA uptake compared with controls, confirming its neurotrophic effect. In vivo studies showed that administration of 3-HM significantly reduced MPTP-induced loss of nigral DA neurons, which is similar to the effect exerted by DM. In the striatum, significant depletion of DA and its metabolites 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA) was observed in MPTP-treated mice, and the levels of all of these biogenic amines were attenuated in lesioned mice that received 3-HM. Compared to DM, the advantage of 3-HM is its neurotrophic effect, which may enhance the sprouting of DA terminal fibers in the striatum, accelerate the formation of DA-containing vesicles, assist the resyn-thesis of DA after lesions, and eventually reestablish the return of the DA system to normal functioning. In addition to the neurotrophic effect, the anti-inflammatory effect exerted by 3-HM resulting from the inhibition of microgliosis generated from the damaged DA neurons induced by MPTP/MPP+ is another important mechanism of 3-HM. 3-HM inhibited the reactive microgliosis in primary mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures after MPTP/MPP+ treatment (Zhang et al., 2006).

Thus, administration of 3-HM in in vivo and in vitro PD models that employ MPTP is beneficial both in reducing DA neuronal degeneration in the substantia nigra pars compacta and reversing the depletion of biogenic amines in the striatum through dual mechanisms - a neurotrophic effect and reduction of reactive microgliosis, consequently providing significant neuro-protection. In contrast to these findings that DM exerts neuroprotection through the inhibition of microglial overactivation, other studies have supported a possible neurotrophic mechanism for DM. In addition, DM prevented the diethyldithiocarbamate [DDC; an inhibitor of superoxide dismutase (SOD)]-enhanced MPTP toxicity in mice (Vaglini et al., 2003). From a histological analysis, they found that the depletion of DA neurons induced by the combined DDC plus MPTP treatment was completely prevented by DM. DM was also effective in preventing the toxicity of glutamate in mesencephalic cell cultures, evaluated via [3H] DA uptake. DM showed the same pattern of protection as nicotine and MK801, both of which increase fibroblastic growth factor in the striatum. This indicates that DM might also work through a neurotrophic mechanism.

Negligible behavioural side effects of DM analogs

The repeated administration of DM or its major metabolite, phencyclidine (PCP)-like dextrorphan (DX), significantly increased locomotor activity and circling behavior, although these behavioral responses were less than those of PCP. 3-HM was the one which had the least behavioral responses mentioned above com pared with DM and DX. In terms of behavioral effects, DM, DX and PCP produced significant behavioral side effects (i.e., CPP and locomotor stimulation), but 3-HM showed very few behavioral side effects (as seen in DM- or DX-treated animals), suggesting that 3-HM has negligible psychotropic effects (Kim et al., 2003b; Zhang et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2008). Thus, it is important to note that the hydroxyl group at position-3 of the morphinan ring system does not always induce psychotropic effects. In addition, these studies did not support earlier reports that the hydroxyl group at position 3 of the morphinan ring system is critical for inducing behavioral side effects (psychotropic activity) as seen for DX (Newman et al., 1992; Tortella et al., 1994).

NALOXONE AS AN OPIOID RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST

Endogenous opioid peptides are recognized to exert their physiological effects through interaction with their respective opioid receptors. These peptides are important in regulating the development of neurons and in modulating a variety of cellular activities, such as the immune response, respiration, ion channel action, and nociceptive/analgesic effects (Chatterjie et al., 1996; Chien and Van Winkle, 1996; Liu et al., 2000a, 2000b; Qin et al., 2005). Naloxone is a potent nonselective antagonist of classic G protein-linked opioid receptors, which are widely expressed on cells in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Naloxone has a similar affinity for the μ-type opioid receptor, as has morphine (Knapp et al., 1995). The action of naloxone as an opiate receptor antagonist is stereospecific: only (-)-naloxone is effective, while the (+)-enantiomer is considered inert at opioid receptors (Iijima et al., 1978).

NEUROPROTECTION PROVIDED BY NALOXONE

Naloxone modulates convulsive behaviours

Earlier studies suggested a role of for inflammation in the pathogenesis of epilepsy (Vezzani and Granata, 2005). Rapid glial activation has been found in the adult and immature brain following seizure activity (Khurgel et al., 1995; Ravizza et al., 2005). Cytokine neosynthesis is induced by seizure in an age-dependent manner (Rizzi et al., 2003; Ravizza et al., 2005). At postnatal day 15 (P15), microglia and astrocytes can be activated after status epilepticus (SE), whereas IL-1 β and S100β are strongly induced (Rizzi et al., 2003; Somera-Molina et al., 2007). A detailed study by Somera-Molina et al. (2007) indicated that primed microglia and persistently activated astrocytes after P15 SE might be responsible for the enhanced vulunerablity to seizure in adulthood. According to these studies, drugs that reduce glial activation may be therapeutically effective in pediatric epilepsy. The influence of naloxone, a potent antagonist at opioid receptors, on seizure activity has been investigated broadly and the results suggest that naloxone may be epileptogenic (Snyder et al., 1980), anticonvulsive (Turski et al., 1985) or inactive (Chen et al., 1976), depending on which models and delivery methods were used. However, naloxone infusion itself did not provoke any seizure activity in normal rats. A continued infusion of naloxone could dose-dependently attenuate not only microglia activation, but also, astrocyte activation after early-life seizures. Naloxone should dose-dependently reduce the vulnerability of immature brain post-seizure. A recent study demonstrated that enhanced glial activation and increased de novo synthesis of glia-derived cytokines (IL-1β and S100β) after P15 SE could be attenuated by naloxone at optimal doses. The precise mechanism of glial activation due to seizures remains elusive. An earlier report demonstrated that naloxone might prevent an unknown mechanism for microglial activation and downstream IL-1β synthesis. IL-1β, produced mainly by activated microglia in the first hours after KA treatment, is one of several powerful inducers of reactive astrogliosis (Oprica et al., 2003). Thus, it is possible that decreasing the synthesis of IL-1β is one way in which naloxone attenuates astrocytic activation. IL-1β has been found to potentiate NMDA neurotoxicity by increasing its channel-gating properties (Viviani et al., 2003). Hence, it is plausible that naloxone can alleviate neuronal death after SE due to the lower level of IL-1β and down-regulation of NMDA activity. Attenuating chronic astrocyte activation is an important way in which naloxone decreases the brain’s vulnerability to SE. S100β is a calcium-binding protein synthesized and released by astrocytes (Donato, 2003). Increased extracellular S100β can stimulate proinflammatory cytokines, increase oxidative stress, and increase susceptibility to neurologic insults (Donato, 2003; Wainwright et al., 2004). Decreasing the S100β concentration by naloxone might contribute to the decreased vulnerability in response to SE, although it depends on experimental conditions.

Naloxone attenuates cerebral ischemia

The pathogenesis of cerebral I/R injury involves cytokine/chemokine production, inflammatory cell in-flux, astrogliosis, cytoskeletal protein degradation, and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (Chen et al., 2001). (-)-Naloxone is able to reduce infarct volume and has been used as a therapeutic agent for cerebral I/R injuries. After cerebral I/R, neuronal damage was strongly associated with gliosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and cytokine/chemokine overproduction. (-)-Naloxone pretreatment suppresses post-ischemia-induced inflammation and neuronal damage. Therefore, (-)-naloxone administration might be an effective therapeutic intervention for reducing ischemic injuries in which an anti-inflammatory mechanism may be involved (Chen et al., 2001). It was suggested that the attenuation of the disturbance of cellular functions following cerebral I/R via restoration of mitochondrial activities or energy metabolism is the mechanism underlying the neuroprotective effect of naloxone. Chen et al. (2001) found that both pre-treatment and post-treatment with naloxone by intracerebroventricular infusion significantly reduced cortical infarct volumes. Pre-treatment with naloxone reduced ischemia-induced suppression of extracellular pyruvate levels and enhancement of the lactate/pyruvate ratio.

Naloxone protects dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPS

Inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration of the DA system in the rat SN and in primary mesencephalic mixed neuronglia cultures resulting from the targeted injection and treatment with LPS is the basis of widely accepted and useful in vivo and in vitro models, respectively. These models can be used to gain further insight into the pathogenesis and therapy of PD.

Microglia, the first line of defense in the brain, produce free radicals such as superoxide, which contributes to neurodegeneration. Chang et al. (2000) studied the effects of naloxone on the production of superoxide from the murine microglial cell line, BV2, stimulated with LPS, as measured by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). The production of superoxide triggered by phobol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) resulted in SOD-inhibitable, catalase-uninhibitable 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) hydroxyl radical adduct formation. LPS enhanced the production of superoxide and triggered the formation of the nonheme iron/nitrosyl complex. Cells pretreated with naloxone showed significant reductions in superoxide production. However, the relationship between the neuroprotective effects of naloxone and microglial activation was not elucidated in this study.

Previous reports suggested that naloxone holds promise as a neuroprotective agent through inhibition of the neuro-inflammation that is characteristic of micro-glial activation (Liu et al., 2000a, 2000b). Treatment of rat mesencephalic mixed neuron-glia cultures with LPS activated microglia and caused them to release proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors (TNFα, NO, IL-10, superoxide, etc.), which subsequently caused damage to midbrain DA neurons. LPS-induced DAergic neurodegeneration was significantly reduced by naloxone. The underlying mechanism for this protective effect of naloxone on DA neurons was shown to be related to inhibition of the activation of microglia and their release of NO, TNFα, and IL-10, and, most importantly, to the superoxide free radical. Naloxone and its inactive stereoisomer (+)-naloxone protected DA neurons with equal potency. These results demonstrate that the underlying mechanism(s) of the neuroprotective effect of naloxone may be closely related to its ability to interfere with activation of microglia and their production of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic factors and that inhibition of microglial-generated superoxide free radicals best correlates with the neuro-protective effects of naloxone isomers (Liu et al., 2000a, 2000b).

In an in vivo model of inflammation-mediated neuro-degeneration, injection of LPS via an osmotic mini-pump into the rat substantia nigra led to the activation of microglia and degeneration of DA neurons: microglial activation was observed as early as 6 h, and loss of DA neurons was detected 3 days after LPS injection (Gao et al., 2002). Furthermore, the LPS-induced loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra was time- and LPS concentration-dependent. Systemic infusion of either (-)-naloxone or (+)-naloxone inhibited the LPS-induced activation of microglia and significantly reduced the LPS-induced loss of nigral DA neurons. These in vivo results, combined with previous observations in the mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures, confirmed that naloxone protected DA neurons against inflammation-mediated degeneration through inhibition of microglial activation and their release of pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic factors (NO, TNFα, IL-10, and superoxide free radicals; Liu et al., 2000a). Thus, these studies demonstrate that both stereoisomers of naloxone attenuate inflammation-mediated DA neurodegeneration in an opioid receptor-independent manner by inhibiting microglial activation both in vitro (Liu et al., 2000a) and in vivo (Liu et al., 2000b).

CONCLUSION

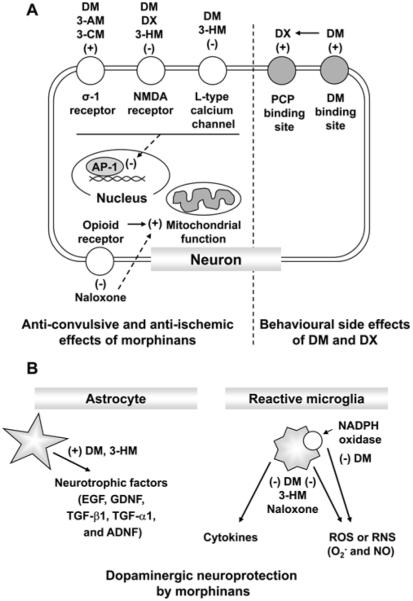

In this review, we demonstrated that DM, a well-known morphinan, produces neuropsychotoxic effects and abuse potential, although DM exhibits diverse positive effects. We showed here that DM shares the basic morphine-like structure with naloxone. In addi tion, we present evidence that morphinan compounds, including DM and its analogs and naloxone offer strong neuroprotection in multiple neurodegenerative disease models by exerting a neurotrophic effect and by modulating glial activation associated with the production of a host of proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors, Thus, morphinans may offer a new therapeutic direction as promising compounds for the treatment of excitotoxic and inflammatory neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Neuropharmacological actions mediated by morphinans

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Brain Research Center from 21st Century Frontier Research Program (# 2010K00812) funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Republic of Korea.

REFERENCES

- Aram JA, Martin D, Tomczyk M, Zeman S, Millar J, Pohler G, Lodge D. Neocortical epileptogenesis in vitro: studies with N-methyl-D-aspartate, phencyclidine, sigma and dextromethorphan receptor ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;248:320–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem JL, Peck R. Dextromethorphan. An overview of safety issues. Drug Saf. 1992;7:190–199. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199207030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokesch PM, Marchand JE, Connelly CS, Wurm WH, Kream RM. Dextromethorphan inhibits ischemia-induced c-fos expression and delayed neuronal death in hippocampal neurons. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:470–477. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199408000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton P, Lu XC, Laskosky MS, Tortella FC. Dextromethorphan protects against cerebral injury following transient, but not permanent, focal ischemia in rats. Life Sci. 1997;60:1729–1740. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carliss RD, Radovsky A, Chengelis CP, O’neill TP, Shuey DL. Oral administration of dextromethorphan does not produce neuronal vacuolation in the rat brain. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RC, Rota C, Glover RE, Mason RP, Hong JS. A novel effect of an opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone, on the production of reactive oxygen species by microglia: a study by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Brain Res. 2000;854:224–229. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AG, Meldrum BS. Non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists protect against sound-induced seizures in DBA/2 mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;166:201–211. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjie N, Alexander GJ, Sechzer JA, Lieberman KW. Prevention of cocaine-induced hyperactivity by a naloxone isomer with no opiate antagonist activity. Neurochem. Res. 1996;21:691–693. doi: 10.1007/BF02527726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Liao SL, Chen WY, Hong JS, Kuo JS. Cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat brain: effects of naloxone. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1245–1249. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105080-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CS, Gates GR, Reynoldson JA. Effect of morphine and naloxone on priming-induced audiogenic seizures in BALB/c mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1976;58:517–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb08618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien GL, Van Winkle DM. Naloxone blockade of myocardial ischemic preconditioning is stereoselective. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1996;28:1895–1900. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Dextrorphan and dextromethorphan attenuate glutamate neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1987;403:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Park M, Hahn E, Choi H, Lim M. Recent trends of drug abuse and drug-associated deaths in Korea. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1025:458–464. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole AE, Eccles CU, Aryanpur JJ, Fisher RS. Selective depression of N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated responses by dextrorphan in the hippocampal slice in rat. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:249–254. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranston JW, Yoast R. Abuse of dextromethorphan. Arch. Fam. Med. 1999;8:99–100. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craviso GL, Musacchio JM. High-affinity dextromethorphan binding sites in guinea pig brain. II. Competition experiments. Mol. Pharmacol. 1983;23:629–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Aldea D, Daneels E, Soliman M, Braksmajer AS, Kopes-Kerr CP. Chronic addiction to dextromethorphan cough syrup: a case report. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2006;19:320–323. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R. Intracellular and extracellular roles of S100 proteins. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2003;60:540–551. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziki M, Honack D, Loscher W. Kindled rats are more sensitive than non-kindled rats to the behavioural effects of combined treatment with MK-801 and valproate. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;222:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90866-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria E, Robles L, Tortella FC. Differential profiles of putative dextromrthorphan sigma ligands in experimental seizure models. FASEB J. 1990;4:A331. [Google Scholar]

- Feeser HR, Kadis JL, Prince DA. Dextromethorphan, a common antitussive, reduces kindled amygdala seizures in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;86:340–345. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferkany JW, Borosky SA, Clissold DB, Pontecorvo MJ. Dextromethorphan inhibits NMDA-induced convulsions. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;151:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90707-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin PH, Murray TF. Identification and initial characterization of high-affinity [3H]dextrorphan binding sites in rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;189:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(90)90233-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Jiang J, Wilson B, Zhang W, Hong JS, Liu B. Microglial activation-mediated delayed and progressive degeneration of rat nigral dopaminergic neurons: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:1285–1297. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Liu B, Zhang W, Hong JS. Critical role of microglial NADPH oxidase-derived free radicals in the in vitro MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2003;17:1954–1956. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0109fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CP, Goldberg MP, Choi DW, Steinberg GK. Dextromethorphan reduces neocortical ischemic neuronal damage in vivo. Brain Res. 1988;440:375–379. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM, Dickinson HA, Kitchen BA. Comparative effects of dextromethorphan and dextrorphan on morphine, methamphetamine, and nicotine self-administration in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;422:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Tomitaka S-I, Narita N, Minabe Y, Iyo M, Fukui S. Induction of heat shock protein HSP-70 in rat retrosplenial cortex following administration of dextromethorphan. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1996;1:235–239. doi: 10.1016/1382-6689(96)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herling S, Solomon RE, Woods JH. Discriminative stimulus effects of dextrorphan in pigeons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1983;227:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman SG. Phencyclidine-like discriminative effects of opioids in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1980;214:614–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman SG. Discriminative stimulus effects of dextromethorphan in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1994;116:249–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02245325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima I, Minamikawa J, Jacobson AE, Brossi A, Rice KC. Studies in the (+)-morphinan series. 5. Synthesis and biological properties of (+)-naloxone. J. Med. Chem. 1978;21:398–400. doi: 10.1021/jm00202a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhoo WK, Shin EJ, Lee YH, Cheon MA, Oh KW, Kang SY, Lee C, Yi BC, Kim HC. Dual effects of dextromethorphan on cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;288:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurgel M, Switzer RC, 3rd, Teskey GC, Spiller AE, Racine RJ, Ivy GO. Activation of astrocytes during epileptogenesis in the absence of neuronal degeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 1995;2:23–35. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1995.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Jhoo WK. Alterations in motor activity induced by high dose oral administration of dextromethorphan throughout two consecutive generations in mice. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1995;18:146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Jhoo WK, Kwan MS, Hong JS. Effects of chronic dextromethorphan administration on the cellular immune responses in mice. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1995;18:267–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Pennypacker KR, Bing G, Bronstein D, Mcmillian MK, Hong JS. The effects of dextromethorphan on kainic acid-induced seizures in the rat. Neurotoxicology. 1996;17:375–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Park BK, Hong SY, Jhoo WK. Dextromethorphan alters the reinforcing effect of cocaine in the rat. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 1997a;19:627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Suh HW, Bronstein D, Bing G, Wilson B, Hong JS. Dextromethorphan blocks opioid peptide gene expression in the rat hippocampus induced by kainic acid. Neuropeptides. 1997b;31:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(97)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Bing G, Jhoo WK, Ko KH, Kim WK, Lee DC, Shin EJ, Hong JS. Dextromethorphan modulates the AP-1 DNA-binding activity induced by kainic acid. Brain Res. 1999;824:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Bing G, Shin EJ, Jhoo HS, Cheon MA, Lee SH, Choi KH, Kim JI, Jhoo WK. Dextromethorphan affects cocaine-mediated behavioral pattern in parallel with a long-lasting Fos-related antigen-immunoreactivity. Life Sci. 2001a;69:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Ko KH, Kim WK, Shin EJ, Kang KS, Shin CY, Jhoo WK. Effects of dextromethorphan on the seizures induced by kainate and the calcium channel agonist BAY k-8644: comparison with the effects of dextrorphan. Behav. Brain Res. 2001b;120:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Nabeshima T, Jhoo WK, Ko KH, Kim WK, Shin EJ, Cho M, Lee PH. Anticonvulsant effects of new morphinan derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001c;11:1651–1654. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Bing G, Jhoo WK, Kim WK, Shin EJ, Im DH, Kang KS, Ko KH. Metabolism to dextrorphan is not essential for dextromethorphan’s anticonvulsant activity against kainate in mice. Life Sci. 2003a;72:769–783. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Shin CY, Seo DO, Jhoo JH, Jhoo WK, Kim WK, Shin EJ, Lee YH, Lee PH, Ko KH. New morphinan derivatives with negligible psychotropic effects attenuate convulsions induced by maximal electroshock in mice. Life Sci. 2003b;72:1883–1895. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klette KL, Decoster MA, Moreton JE, Tortella FC. Role of calcium in sigma-mediated neuroprotection in rat primary cortical neurons. Brain Res. 1995;704:31–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp PE, Maderspach K, Hauser KF. Endogenous opioid system in developing normal and jimpy oligodendrocytes: mu and kappa opioid receptors mediate differential mitogenic and growth responses. Glia. 1998;22:189–201. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199802)22:2<189::aid-glia10>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp RJ, Malatynska E, Collins N, Fang L, Wang JY, Hruby VJ, Roeske WR, Yamamura HI. Molecular biology and pharmacology of cloned opioid receptors. FASEB J. 1995;9:516–525. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.7.7737460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gal La Salle G, Calvino B, Ben-Ari Y. Morphine enhances amygdaloid seizures and increases inter-ictal spike frequency in kindled rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1977;6:255–260. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(77)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leander JD. Evaluation of dextromethorphan and carbetapentane as anticonvulsants and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid antagonists in mice. Epilepsy Res. 1989;4:28–33. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(89)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Du L, Hong JS. Naloxone protects rat dopaminergic neurons against inflammatory damage through inhibition of microglia activation and superoxide generation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000a;293:607–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Jiang JW, Wilson BC, Du L, Yang SN, Wang JY, Wu GC, Cao XD, Hong JS. Systemic infusion of naloxone reduces degeneration of rat substantia nigral dopaminergic neurons induced by intranigral injection of lipopolysaccharide. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000b;295:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Qin L, Wilson BC, An L, Hong JS, Liu B. Inhibition by naloxone stereoisomers of beta-amyloid peptide (1-42)-induced superoxide production in microglia and degeneration of cortical and mesencephalic neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;302:1212–1219. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscher W, Honack D. Responses to NMDA receptor antagonists altered by epileptogenesis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991;12:52. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90496-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann HJ, Scheid M. Dextromethorphan attenuates hypoxia-induced neuronal dysfunction in rat neocortical slices. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;178:171–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn LG, Kerchner GA, Kalra V, Zimmerman DM, Leander JD. Phencyclidine receptors in rat brain cortex. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984;33:3529–3535. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Choi DW. Morphinans attenuate cortical neuronal injury induced by glucose deprivation in vitro. Brain Res. 1988;446:144–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray TF, Leid ME. Interaction of dextrorotatory opioids with phencyclidine recognition sites in rat brain membranes. Life Sci. 1984;34:1899–1911. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer R, Pflimlin P, Trube G. Dextromethorphan blocks N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced currents and voltage-operated inward currents in cultured cortical neurons. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;238:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90849-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Bevan K, Bowery N, Tortella FC. Synthesis and evaluation of 3-substituted 17-methylmorphinan analogs as potential anticonvulsant agents. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:4135–4142. doi: 10.1021/jm00100a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Labruyere J, Price MT. Pathological changes induced in cerebrocortical neurons by phencyclidine and related drugs. Science. 1989;244:1360–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.2660263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprica M, Eriksson C, Schultzberg M. Inflammatory mechanisms associated with brain damage induced by kainic acid with special reference to the interleukin-1 system. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2003;7:127–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2003.tb00211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvirenti L, Balducci C, Koob GF. Dextromethorphan reduces intravenous cocaine self-administration in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;321:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Block ML, Liu Y, Bienstock RJ, Pei Z, Zhang W, Wu X, Wilson B, Burka T, Hong JS. Micro-glial NADPH oxidase is a novel target for femtomolar neuroprotection against oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2005;19:550–557. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2857com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirion R, Bowen WD, Itzhak Y, Junien JL, Musacchio JM, Rothman RB, Su TP, Tam SW, Taylor DP. A proposal for the classification of sigma binding sites. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13:85–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90030-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravizza T, Rizzi M, Perego C, Richichi C, Veliskova J, Moshe SL, De Simoni MG, Vezzani A. Inflammatory response and glia activation in developing rat hippocampus after status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 5):113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi M, Perego C, Aliprandi M, Richichi C, Ravizza T, Colella D, Veliskova J, Moshe SL, De Simoni MG, Vezzani A. Glia activation and cytokine increase in rat hippocampus by kainic acid-induced status epilepticus during postnatal development. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003;14:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogawski MA, Porter RJ. Antiepileptic drugs: pharmacological mechanisms and clinical efficacy with consideration of promising developmental stage compounds. Pharmacol. Rev. 1990;42:223–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Loh HH. Effects of opioids on the immune system. Neurochem. Res. 1996;21:1375–1386. doi: 10.1007/BF02532379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, Minami M. Molecular pharmacology of the opioid receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;68:343–364. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)02011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp FR, Butaman M, Aardalen K, Nickolenko J, Nakki R, Massa SM, Swanson RA, Sagar SM. Neuronal injury produced by NMDA antagonists can be detected using heat shock proteins and can be blocked with antipsychotics. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1994;30:555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EJ, Nabeshima T, Lee PH, Kim WK, Ko KH, Jhoo JH, Jhoo WK, Cha JY, Kim HC. Dime-morfan prevents seizures induced by the L-type calcium channel activator BAY k-8644 in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2004;151:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EJ, Nah SY, Kim WK, Ko KH, Jhoo WK, Lim YK, Cha JY, Chen CF, Kim HC. The dextromethorphan analog dimemorfan attenuates kainate-induced seizures via sigma1 receptor activation: comparison with the effects of dextromethorphan. Br. J. Pharm acol. 2005;144:908–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EJ, Nah SY, Chae JS, Bing G, Shin SW, Yen TP, Baek IH, Kim WK, Maurice T, Nabeshima T, Kim HC. Dextromethorphan attenuates trimethyltin-induced neurotoxicity via sigma1 receptor activation in rats. Neurochem. Int. 2007;50:791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EJ, Lee PH, Kim HJ, Nabeshima T, Kim HC. Neuropsychotoxicity of abused drugs: potential of dextromethorphan and novel neuroprotective analogs of dextromethorphan with improved safety profiles in terms of abuse and neuroprotective effects. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;106:22–27. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fm0070177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EW, Shearer DE, Beck EC, Dustmann RE. Naloxone-induced electrographic seizures in the primate. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1980;67:211–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00431258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somera-Molina KC, Robin B, Somera CA, Anderson C, Stine C, Koh S, Behanna HA, Van Eldik LJ, Watterson DM, Wainwright MS. Glial activation links early-life seizures and long-term neurologic dysfunction: evidence using a small molecule inhibitor of pro-inflammatory cytokine upregulation. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1785–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg GK, Lo EH, Kunis DM, Grant GA, Poljak A, Delapaz R. Dextromethorphan alters cerebral blood flow and protects against cerebral injury following focal ischemia. Neurosci. Lett. 1991;133:225–228. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90575-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmiller CL, Maisonneuve IM, Glick SD. Effects of dextromethorphan on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: Interactions with morphine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003;74:803–810. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takazawa A, Anderson P, Abraham WC. Effects of dextromethorphan, a nonopioid antitussive, on development and expression of amygdaloid kindled seizures. Epilepsia. 1990;31:496–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb06097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella FC, Musacchio JM. Dextromethorphan and carbetapentane: centrally acting non-opioid antitussive agents with novel anticonvulsant properties. Brain Res. 1986;383:314–318. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella FC, Martin DA, Allot CP, Steel JA, Blackburn TP, Loveday BE, Russell NJ. Dextromethorphan attenuates post-ischemic hypoperfusion following incomplete global ischemia in the anesthetized rat. Brain Res. 1989a;482:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella FC, Pellicano M, Bowery NG. Dextromethorphan and neuromodulation: old drug coughs up new activities. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1989b;10:501–507. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella FC, Robles L, Witkin JM, Newman AH. Novel anticonvulsant analogs of dextromethorphan: Improved efficacy, potency, duration and side-effect profile. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella FC, Britton P, Williams A, Lu XC, Newman AH. Neuroprotection (focal ischemia) and neurotoxicity (electroencephalographic) studies in rats with AHN649, a 3-amino analog of dextromethorphan and low-affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;291:399–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trube G, Netzer R. Dextromethorphan: cellular effects reducing neuronal hyperactivity. Epilepsia. 1994;35(Suppl 5):S62–S67. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb05972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turski L, Ikonomidou C, Cavalheiro EA, Kleinrok Z, Czuczwar SJ, Turski WA. Effects of morphine and naloxone on pilocarpine-induced convulsions in rats. Neuropeptides. 1985;5:315–318. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(85)90016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglini F, Pardini C, Bonuccelli U, Maggio R, Corsini GU. Dextromethorphan prevents the diethyldithiocarbamate enhancement of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine toxicity in mice. Brain Res. 2003;973:298–302. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02538-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A, Granata T. Brain inflammation in epilepsy: experimental and clinical evidence. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1724–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani B, Bartesaghi S, Gardoni F, Vezzani A, Behrens MM, Bartfai T, Binaglia M, Corsini E, Di Luca M, Galli CL, Marinovich M. Interleukin-1beta enhances NMDA receptor-mediated intracellular calcium increase through activation of the Src family of kinases. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:8692–8700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08692.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright MS, Craft JM, Griffin WS, Marks A, Pineda J, Padgett KR, Van Eldik LJ. Increased susceptibility of S100B transgenic mice to perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;56:61–67. doi: 10.1002/ana.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe TR, Caravati EM. Massive dextromethorphan ingestion and abuse. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1995;13:174–176. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Otton SV, Kalow W, Sellers EM. Effects of route of administration on dextromethorphan pharmacokinetics and behavioral response in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;274:1431–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang PP, Huang EY, Yeh GC, Tao PL. Co-administration of dextromethorphan with methampheta-mine attenuates methamphetamine-induced rewarding and behavioral sensitization. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006;13:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A, Gasior M, Geter-Douglass B, Tortella FC, Newman AH, Witkin JM. Attenuation of the stimulant and convulsant effects of cocaine by 17-substituted-3-hydroxy and 3-alkoxy derivatives of dextromethorphan. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003;74:313–323. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang T, Qin L, Gao HM, Wilson B, Ali SF, Hong JS, Liu B. Neuroprotective effect of dextromethorphan in the MPTP Parkinson’s disease model: role of NADPH oxidase. FASEB J. 2004;18:589–591. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0983fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Qin L, Wang T, Wei SJ, Gao HM, Liu J, Wilson B, Liu B, Kim HC, Hong JS. 3-hydroxymorphinan is neurotrophic to dopaminergic neurons and is also neuroprotective against LPS-induced neurotoxi-city. FASEB J. 2005;19:395–397. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1586fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Shin EJ, Wang T, Lee PH, Pang H, Wie MB, Kim WK, Kim SJ, Huang WH, Wang Y, Hong JS, Kim HC. 3-Hydroxymorphinan, a metabolite of dextromethorphan, protects nigrostriatal pathway against MPTP-elicited damage both in vivo and in vitro. FASEB J. 2006;20:2496–2511. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6006com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou GZ, Musacchio JM. Computer-assisted modeling of multiple dextromethorphan and sigma binding sites in guinea pig brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;206:261–269. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90108-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]