Summary

The embryonic tentorial sinus usually regressses during postnatal development, but its typical prenatal drainage patterns and intradural anastomoses can be depicted as various developmental phenotypic representations. Here, we tried to clarify the variant types of the superficial middle cerebral vein (SMCV) associated with the embryonic tentorial sinus.

Total 41 patients and 82 hemispheres were included in this study. CT angiography was performed in all patients as screening for cerebrovascular disease or other intracranial disorders. A separate workstation and 3D software were used to evaluate the cranial venous systems with 3D volume rendering techniques, thin-slice MIP images, and MPR techniques for the analysis of its complicated angioarchitecture. Variations of the SMCV were classified according to the developmental alterations of the embryonic tentorial sinus, including sphenoparietal sinus (cranial remnant of tentorial sinus), basal sinus (floor of middle cranial fossa), petrosal and caudal remnant of the tentorial sinus. Secondary intradural anastomoses of cavernous and superior petrosal sinuses were also evaluated for the efferent pathways.

The most frequent type of remnant tentorial sinus, sphenoparietal sinus was present in 49% (40/82) of hemispheres examined. Other regressed patterns of embryonic tentorial sinus were also identified in 38% (31/82): nine caudal remnant type around the transverse sinus, 12 petrosal type, one basal type, five unclassified cases, and mixed type were found in four cases. Secondary intradural cavernous sinus anastomosis was seen in 44% (36/82), however the most prevalent pattern was no anastomosis (46/82) with cavernous sinus. Only one case of superior petrosal sinus anastomosis was found in this series associated with basal sinus type.

Anatomic variations of SMCV can be clearly demonstrated with embryologic aspects of the tentorial sinus according to its developmental regression and postnatal secondary adaptations of cerebral venous drainage.

Key words: superficial middle cerebral vein, embryology, tentorial sinus

Introduction

The superficial middle cerebral vein (SMCV) often has common anatomic variations and has also been classified with various definitions by several authors1-4. So it is still confusing to describe the SMCV considering areas of its venous drainage and anastomoses precisely. The possibility to understand anatomic variations should based its embryologic anatomy.

Anatomic visualization of cerebral venous systems can be obtained with three-dimensional (3D) CT angiography5 which can also analyze the morphologic characteristics of SMCV and its anatomic relationships with bone and cerebral arteries6. Following volume acquisition of CT angiography, computerized manipulations of the data will readily allow the simulation of various anatomical structures performed with strenuous cadaveric dissections and also make it possible to stand inside or outside the space with virtual imaging tools using CT angiography data.

We present our findings concerning the patterns of SMCV as seen on 82 hemispheres of CT angiography, focusing on the embryologic anatomy of the embryonic regressed tentorial sinus as it may normally appear in routine clinical practice.

Material and Methods

The drainage patterns of the SMCV were prospectively evaluated on 50 consecutive diagnostic CT angiography studies performed between July and November at the hospital. All the patients included were screened for any cerebrovascular diseases or other intracranial diseases. A total 41 patients and 82 hemispheres were included in this study protocol of cerebral CT angiography. Fourteen men and 27 women, aged from 30 to 77 years (mean age, 56 years) were examined. Among them, eight patients had intracranial atherosclerotic diseases with variable degrees of stenosis. Four patients with incidental small aneurysms were detected (two had mirror aneurysms of the MCA bifurcation). One patient with a small acute ischemic infarction in the basal ganglia was suggested, and one patient had suggestive findings of vertebrobasilar dissection. No other intracranial abnormalities were detected.

Three-dimensional CT angiography was initiated 22-28 seconds after the start of intravenous bolus administration of non-ionizing contrast material, injected at a rate of 4-5 mL/s for 20-25 seconds, for a total volume of 100 mL. The sections were 1.25 mm thick with 0.6 mm slice spacing. The FOV was 180 mm in each dimension and covered a brain region of 60 mm in a caudal to cranial scan direction. The angle of CT gantry axis was adjusted before the scan for visualization of the circle of Willis and the cerebral venous system. The raw image data of CT were transferred to PACS monitors and also to a separate PC workstation. We used the volume rendering method for 3D reconstruction with various tools including MPR, MIP, SSD, and virtual endoscopy in the software program (Rapidia 2.7, Infinitt, Seoul, Korea).

Variations of the SMCVs in the patients were classified according to alterations occurring during venous development in the embryo, as described in the following figures (figure 1).

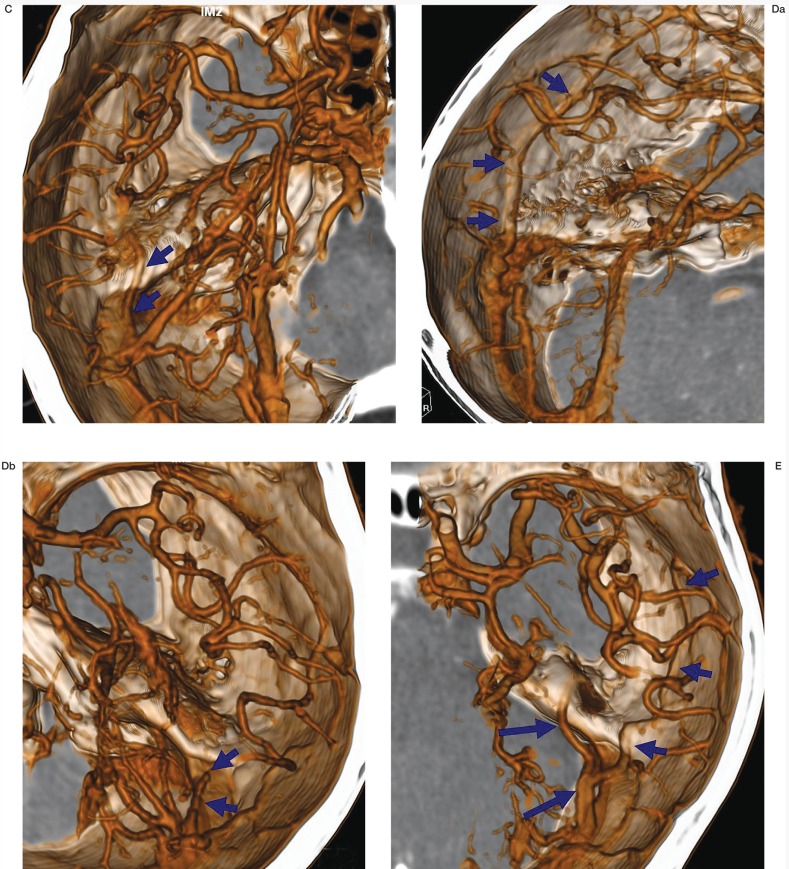

Figure 1.

Classifications of the SMCV (Superficial Middle Cerebral Vein) related to the remnant embryonic tentorial sinus. A) Sphenoparietal sinus (cranial remnant type of tentorial sinus) type: the SMCV (arrows) runs along the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone to enter/or not enter the cavernous sinus. B) Basal sinus type: the SMCV (arrows) runs along the lesser wing, turns downward along the floor of the middle cranial fossa, and runs over the petrous bone to enter the transverse sinus. C) Petrosal type of tentorial sinus: the SMCV (arrows) fails to connect to the sphenoparietal sinus anteriorly, and directed backward over the petrous pyramid and runs posteriorly to join the transverse sinus. D) Caudal remnant type: the SMCV is absent or underdeveloped and the venous drainage of middle cerebral vein is largely directed to the cortical vein (a, cortical caudal remnant type) draining into the transverse sinus, or with small residual venous channels (b) attached to the transverse sinus. E) Mixed type: the SMCV shows mixed appearances of remnant regressed tentorial sinus.This figure shows small a superior petrosal sinus and petrosal type (long arrows) and cortical caudal remnant type (short arrows) draining to the mid-portion of transverse sinus.

Results

The most frequent type of remnant tentorial sinus, sphenoparietal sinus was present in 49% (40/82) of examined hemispheres. Other regressed patterns of embryonic tentorial sinus were also identified in 38% (31/82): nine caudal remnant type around the transverse sinus including three (3/9) cortical caudal remnant type (figure 1, Da) draining into transverse sinus, 12 petrosal type, one basal type, five unclassified cases and any combination of the above (mixed type) were found in four cases.

Secondary intradural cavernous sinus anastomosis was seen in 44% (36/82), but the most prevalent pattern was no anastomosis (46/82) with cavernous sinus. Only one case of superior petrosal sinus anastomosis was found in this series associated with basal sinus type.

Discussion

Embryologic aspects of regressed tentorial sinus with the SMCV

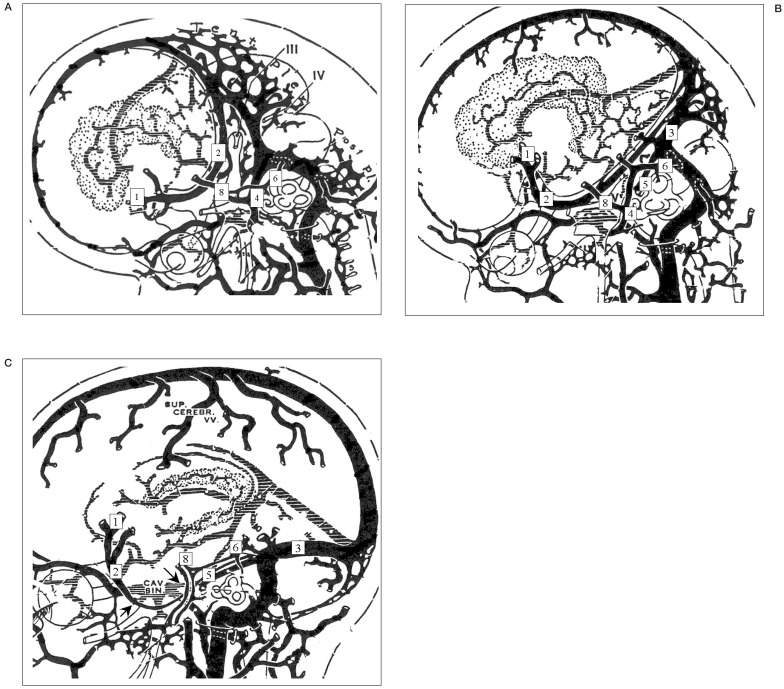

The cerebral venous dispositions in adult configuration are still a matter of debate, especially on the SMCV. The embryonic tentorial sinus, which drains cortical blood coming from the SMCV, migrates medially toward the cavernous sinus region during the eighth week of gestation7. The SMCVs with pial tributaries are still directly continuous with the tentorial sinus in this stage and this has been elongated by the growing hemispheres to join the primitive transverse sinus distally 8. In Stage 7a (60-80 mm), the cerebral growth and expansion of the otic capsule leads to formation of the superior petrosal sinus that is the dural end of the ventral metencephalic (great anterior cerebellar) vein. At this point, the primitive transverse sinus has been swung backward on the sigmoid sinus, and receives blood flow from the elongated tentorial sinus continuous with the SMCVs. The prootic sinus which develops in the otic capsule region is continuous with the definitive petrosquamosal sinus caudally and constitutes the flow into the cavernous sinus medially. The petrosquamosal sinus and remnant of the prootic sinus drain the dura and bone to become diploic in the adult and continue through the foramen ovale. The middle meningeal sinuses accompanied by the middle meningeal artery can be connected with the remnant of the prootic sinus and can also be drained through the foramen ovale and temporal emissary veins (figure 2). Two secondary intradural anastomoses involving the cavernous sinus have generally developed before the adult stage: one is between the tentorial sinus in the position of sphenoparietal sinus and the anterior end of the cavernous sinus (figure 2C,G, arrows). Whereas the caudal part of the dwindled tentorial sinus drains into the transverse sinus, the other is between the cavernous sinus and the superior petrosal sinus (figure 2C,G, arrows). The adult configuration of the SMCV is based on the relative development of the pathway from pial veins through the tentorial sinus towards the transverse sinus and the development of the anastomosis between the cavernous sinus to the pterygoid plexus (future correspondence of the remnant prootic sinus) and petrosal sinuses.

Figure 2.

Embryologic developmental stages of the cerebral veins related to the tentorial sinus and prootic sinus by Padget DH8. A) Stage 7, 40-mm stage. The SMCV with pial tributaries are directly continuous with the tentorial sinus and this has been elongated by the growing hemispheres and joins the primitive transverse sinus. B) Stage 7a, 6080 mm stage. The tentorial sinus, constituting the primary drainage of the middle cerebral veins, often follows the edge of the lesser sphenoid wing. Expansion of the otic capsule leads to the formation of the superior petrosal sinus that is the dural end of the great anterior cerebellar vein. The prootic sinus is continuous with the definitive petrosquamosal sinus. C) Infant or adult stage. The petrosquamosal sinus and the remnant of the prootic sinus draining the dura and bone, become diploic in adult life. Remnants of the tentorial sinus frequently persist and may anastomose with the cavernous sinus, also with the superior petrosal sinus. D & E) Stage 7a, 60-80 mm stage. The tentorial sinus constituting primary drainage of the SMCVs often follows the edge of the sphenoid wing to become plexiform caudally as it is shifted towards the sigmoid sinus. F) Infant or G) adult stage. The SMCVs drain through the remnants of the tentorial sinus, which has a variable position, or secondarily anastomose with the cavernous sinus. The typical lateral wing of the cavernous sinus, just below the mandibular nerve root, is a remnant of the prootic sinus, and extends to the foramen ovale. The opthalmomeningeal sinus accompanies the artery of the MMA and ophthalmic lachrymal artery also being diploic, and continues towards the superior ophthalmic vein along the sphenoid ridge, towards the remnant prootic sinus.

1, SMCV;

2, tentorial sinus;

3, transverse sinus;

4, prootic sinus;

5, superior petrosal sinus;

6, petrosquamosal sinus;

7, cavernous sinus and inferior pet rosal sinus;

8, middle meningeal sinus

9, ophthalmomeningeal sinus;

10,superior ophthalmic vein; arrows (in figure 2C,G), site of secondary anastomoses.

The sphenoparietal sinus, the cranial remnant of the tentorial sinus is the most frequent type of anatomic variation of the SMCV in the adult stage regardless of the presence of anastomosis with the cavernous sinus. The hypothesis of the formation of sphenoparietal sinus is that the embryonic tentorial sinus should be entirely regressed by the growing hemispheres except only in the preservation of the cranial remnant.

In our series, the absence of anastomosis with the cavernous sinus was slightly more prevalent than the presence of anastomosis. The cavernous sinus drains prenatally only to the ophthalmic vein via the inferior petrosal sinus through the internal jugular vein, while the cerebral veins have no connections with the cavernous sinus, but converge into the transverse sinus8. In most infants this is still the case, but in the typical adult configuration connections to the cavernous sinus have developed via the medial extension of the sphenoparietal sinus9. The laterocavernous sinus in the lateral dural layers of the cavernous sinus could also participate in the formation of anastomosis with sphenoparietal sinus7. The SMCV is then connected to the cavernous sinus directly via the sphenoparietal sinus. Therefore the cavernous sinus anastomosis would be considered for venous outflow from the sphenoparietal sinus coming from the SMCVs.

On the contrary, no cavernous sinus anastomosis could be postulated as the sphenoparietal sinus from the SMCVs will constitute either the venous outflow toward the deep middle cerebral veins or the venous reservoir. The basal sinus type of SMCVs acquires the typical venous disposition of the embryonic tentorial sinus itself as the adult configurations (figure 1). The incidence of this pattern seems to be quite rare assuming that the basal sinus type is the fully persisted venous route of the SMCVs through the tentorial sinus at 60-80 mm stage. The human tentorial sinus, lying in the path of the tentorial nerve in the adult, often has the appearance of a vein that is attached to or lies just within the innermost layer of tentorial dura, after following the edge of the lesser sphenoid wing 8. Padget also pointed out that the tentorium, which is embryologically attached to the cartilaginous anterior clinoid process, arises at the site of the future temporal fossa. Therefore, she suggested that the term sphenotemporal sinus is appropriate for the postnatal position of the tentorial sinus. In our case, the SMCVs constituted the pattern of basal sinus type routed via the sphenoparietal sinus and turned laterally along the floor of the temporal fossa, running along the petrous pyramid and terminating in the transverse sinus. This case also depicted the rare pattern of anastomosis with the superior petrosal sinus from the regressed tentorial sinus.

The petrosal type of the SMCVs manifested as the most frequent regressed pattern of the tentorial sinus other than the sphenoparietal sinus. This configuration was also described in the previous literature as temporal/or petrosal bridging veins 10. The caudal remnant type of the SMCVs has two subtypes; one is the large cortical venous structure directed into the transverse sinus along the squamosal part of temporal bone, and the other is the small remnant type of the SMCVs only attached to the transverse sinus. Several authors described the large, cortical caudal remnant type as the squamosal type and sphenopetrosal sinus, respectively 3,10. Compared with the basal sinus type, the cortical caudal remnant type has an undeveloped/or underdeveloped sphenoparietal sinus. The small remnant type of the SMCVs has attached into the transverse sinus and is often difficult to discriminate from adjacent cerebellar veins. The groups of anterior and posterior cerebellar veins empty into the superior petrosal and transverse sinuses, respectively. In many cases, the posterior cerebellar veins are collected by a channel constituting a cerebellar tentorial sinus, superiorly and inferiorly. This lacuna, sometimes duplicated, lies in the tentorium near the torcular, and may be confluent with the caudal end of the cerebral tentorial sinus in prenatal life 8. Therefore, the course of this small caudal remnant type of the SMCVs should be parallel with the tentorium, terminate in the transverse sinus and the tapered remnant of the tentorial sinus should face towards the petrous pyramid bone.

The emissary type of the SMCVs has been described by some authors 1-3. Those large sphenoid emissary veins, so-called "rete" of the foramen ovale, connect the lateral wing of the cavernous sinus and also the middle meningeal sinus into the pterygoid plexus8. This type of venous drainage from the SMCVs typically shows the persistence of ophthalmomeningeal sinuses in prenatal life. In our cases of unclassified types, some hemispheres had the small venous tributaries taking the direction into the foramen ovale, but without scan coverage it was not possible to document this type of variation.

Clinical implications of SMCV variations

The anatomy and pathophysiology of the cerebral venous system have been underestimated due to theoretical preoccupations with the arterial blood supply and circulation of CSF 9. The understanding of the development of the vascular system in relation to its territories and adjacent structures facilitates the anticipation of possible anatomic variations and clinical syndromes.

The importance of cerebral venous anatomy in interventional neuroradiology is still fundamental and should be reemphasized considering the potential understanding of various cerebral venous diseases. The variations of SMCVs should be assessed, especially the dural AV fistulas (dAVF) with cortical venous congestions. The explanations of the non-benign neurologic symptoms due to venous congestion in dAVF could be described with the development of venous collaterals and venous reroutings11,12. The signs and symptoms of retrograde venous congestion could be predicted by dAVF drainage into the superior petrosal sinus, which then drains into cortical veins and tortuous and dilated cortical veins draining away from the cavernous sinus dAVF 12. These findings suggest that postnatal secondary anastomosis between the superior petrosal sinus and any possible remnant variations of the SMCVs could be a potential route of venous rerouting or collaterals. From a neurosurgeon's perspective, preoperative understanding of the variant venous anatomy is more critical to minimize complications resulting from venous outflow obstruction during a combined petrosal approach involving the temporal lobe. The variant types of the SMCVs, mostly basal sinus type and cortical caudal remnant type, can be matched with the previous results of the sphenopetrosal type of temporal venous drainage on angiographic study 10. This type of venous drainage limits temporal lobe mobility in the subtemporal approaches because the vein is tightly adhered to the middle cranial fossa. In this situation, the collateral venous outflow patterns must be evaluated and a different operative approach should be considered to reduce the likelihood of possible venous complications.

Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the venous drainage patterns including SMCV variations, the vein of Labbe, and dural sinuses in preoperative CT venograms for preservation of normal venous drainage planning lateral cranial base surgery.

References

- 1.Wolf BS, Huang YP, Newman CM. The superficial sylvian venous drainage system. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;89:398–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.San Millan Ruiz D, Gailloud P, et al. Laterocavernous sinus. Anat Rec. 1999;254:7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990101)254:1<7::AID-AR2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki Y, Matsumoto K. Variations of the superficial middle cerebral vein: classification using three-dimensional CT angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:932–938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott JN, Farb RI. Imaging and anatomy of the normal intracranial venous system. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2003;13:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5149(02)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casey SO, Alberico RA, et al. Cerebral CT venography. Radiology. 1996;198:163–70. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.1.8539371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaminogo M, Hayashi H, et al. Depicting cerebral veins by three-dimensional CT angiography before surgical clipping of aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:85–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gailloud P, San Millan Ruiz D, et al. Angiographic anatomy of the laterocavernous sinus. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1923–1929. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padget DH. The cranial venous system in man in reference to development, adult configuration, and relation to the arteries. Am J Anat. 1956;98:307–355. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000980302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andeweg J. The anatomy of collateral venous flow from the brain and its value in aetiological interpretation of intracranial pathology. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:621–628. doi: 10.1007/s002340050321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakata K, Al-Mefty O, Yamamoto I. Venous consideration in petrosal approach: microsurgical anatomy of the temporal bridging vein. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:153–160. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200007000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willinsky R, Goyal M, et al. Tortuous, engorged pial veins in intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas: correlations with presentation, location, and MR findings in 122 patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1031–1036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stiebel-Kalish H, Setton A, et al. Cavernous sinus dural arteriovenous malformations: patterns of venous drainage are related to clinical signs and symptoms. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1685–1691. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]