Abstract

Importance of the field

Recent advances in understanding the oncogenesis of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) have revealed multiple dysregulated signaling pathways. One frequently altered axis is the EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. This pathway plays a central role in numerous cellular processes including metabolism, cell growth, apoptosis, survival and differentiation, which ultimately contributes to HNSCC progression.

What the reader will gain

This article reviews the current understanding of EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in HNSCC, including the impact of both genetic and epigenetic alterations. This review further highlights the potential of targeting this signaling cascade as a promising therapeutic approach in the treatment of HNSCC.

Areas covered in this review

Books, journals, databases and websites have been searched to provide a current review on the subject.

Take home message

Genetic alterations of several nodes within this pathway, including both genetic and epigenetic changes, leading to either oncogene activation or inactivation of tumor suppressors, have frequently been implicated in HNSCC. Consequently, drugs that target the central nodes of this pathway have become attractive for molecular oriented cancer therapies. Numerous preclinical and clinical studies are being performed in HNSCC, however, more studies are still needed to better understand the biology of this pathway.

Keywords: Akt, EGFR, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, mTOR, PI3K, targeted therapy

1. Introduction

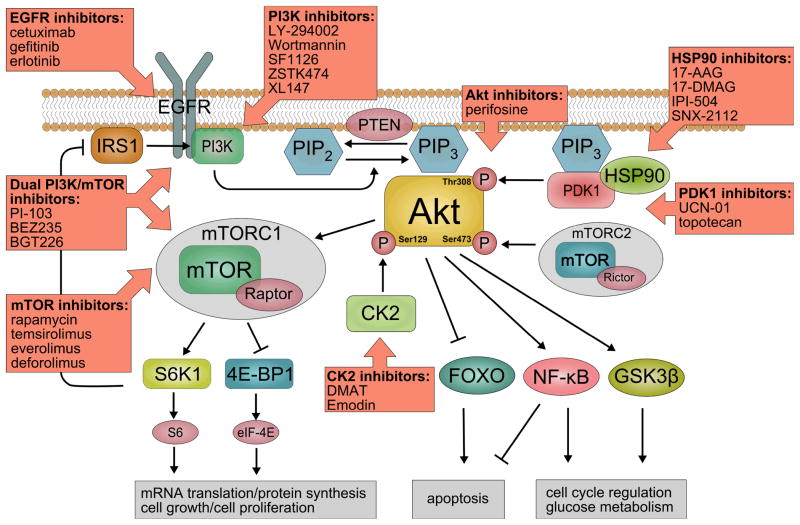

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common type of cancer with an annual incidence of approximately 600,000 worldwide and a five year survival rate of 50%, showing only little improvement over the last 20 years 1. HNSCC comprises cancers arising from five major anatomical sites: oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx. Recent studies have focused on the genetic and epigenetic alterations of HNSCC 2, providing better understanding of the molecular events underlying the pathogenesis of HNSCC. One of the most frequently altered signaling pathways in HNSCC is the EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR cascade (Figure 1). Several genetic and epigenetic mechanisms contribute to these alterations, providing multiple targets for molecular oriented therapy in HNSCC (Table 1). This review focuses on central nodes within this pathway including EGFR, PI3K, PTEN, PDK1, Akt and mTOR, revealing their common alterations in HNSCC and their potential role for targeted molecular therapy.

Figure 1.

Current Understanding of EGFR-PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas and potential drugs for Molecular-Oriented Therapy.

Table 1.

Overview of clinical trials with molecular oriented therapies targeting key nodes in the EGFR-PI3K-Akt-mTor pathway. Due to multiple ongoing studies using cetuximab, only two key clinical trials are listed, which led to the FDA approval for cetuximab as single-agent therapy for platinmum-refractory recurrent/metastatic HNSCC and for the combination of cetuximab and RT for the treatment of unresectable HNSCC.

| EGFR inhibitors | |||||

| Cetuximab | Combination with radiation therapy | Phase III | Bonner et al. 26 | Stage III/IV HNSCC | |

| Single agent | Phase III | Vermorken et al. 28 | Recurrent or metastatic HNSCC | ||

| Combination with radiation therapy and cisplatin | Phase III | NCT00265941 | Stage III/IV HNSCC | ||

| Gefitinib | Combination therapy with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib | Phase I | Wirth et al. 115 | Recurrent or metastatic HNSCC | |

| Combination therapy with radiation therapy ± cisplatin | Phase I | Chen et al. 116 | Locally advanced HNSCC | ||

| Single agent | Phase II | Cohen et al. 31 | Recurrent or metastatic HNSCC | ||

| mTor inhbitors | |||||

| Temsirolimus (CCI-779) | Combination therapy with EGFR inhibitor erlotinib | Phase II | NCT01009203 | Platinum-Refractory or -Ineligible, advanced, HNSCC | |

| Combination therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin | Phase I/II | NCT01016769 | Recurrent or metastatic HNSCC | ||

| Combination therapy with cisplatin and cetuximab | Phase I/II | NCT01015664 | Recurrent or metastatic HNSCC | ||

| Everolimus (RAD001) | Combination therapy with docetaxel and cisplatin | Phase I | NCT00935961 | Local-regional advanced HNSCC | |

| Combination therapy with intensity modulated radiation therapy and cisplatin | Phase I | NCT00858663 | Head and Neck Cancer | ||

| Akt inhibitors | Perifosine | Single agent | Phase II | Argiris et al. 96 NCT00062387 | Recurrent or metastatic HNSCC |

| HSP90 inhibitors | 17-DMAG | Single agent | Phase I | NCT00089362 | Metastatic or unresectable Head and Neck cancer |

2. EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling

Multiple ligands activate epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), including epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), amphiregulin, heregulin, and heparin binding-EGF 3, leading to the activation of Class I phosphoinositide – 3 kinases (PI3K). Once activated, PI3K phosphorylates phosphotatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate [PtdIns(4,5)P2] generating phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate [PtdIns(3,4,5)P3] 4. PTEN (phosphate and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10), an important tumor suppressor, antagonizes PI3K function by dephosphorylating PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to PtdIns(4,5)P2 5. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 initiates Akt activation by its translocation to the plasma membrane, leading to a conformational change in Akt. Subsequently, Akt is phosphorylated at three regulatory sites: Thr308 in the activation loop of the catalytic domain by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) 6, Ser473 in the COOH-terminal domain by mTOR-RICTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin-rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR) complex 7 and a recently discovered Ser129 by casein kinase 2 (Di Maira et al. 2005). Once activated, Akt phosphorylates multiple downstream targets involved in key cellular processes including apoptosis, metabolism, cell proliferation and cell growth. Akt promotes cell survival by blocking the function of pro-apoptotic proteins and promoting the induction of cell survival proteins 8. Akt can also activate the anti-apoptotic NF-κB pathway through phosphorylation and activation of IKKα which with IKKβ then phosphorylates the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα 9. Furthermore, Akt phosphorylates the FOXO family members: FOXO, FOXO3a and FOXO4, inducing their export from the nucleus preventing FOXO-mediated transcription of pro-apoptotic targets 10. Another major downstream effector of Akt is mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Activation of mTORC1 is initiated by Akt-mediated phosphorylation and sequential inactivation of the tuberous sclerosis complex. The tuberous sclerosis complex consists of tumor-suppressor protein TSC2 (tuberin) associated with another tumor-suppressor protein TSC1 (hamartin) 11. Once phosphorylated, the tuberous sclerosis complex loses its ability to suppress Rheb1, which subsequently activates mTORC1 12.

2.1 Targeting EGFR

One extensively studied receptor tyrosine kinase upstream of PI3K/Akt signaling is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, also known as HER-1 or ErbB-1). Overexpression of EGFR has been identified in many cancers from epithelial origins, including HNSCC, where overexpression of EGFR is found in over 95% of all tumors 13,14,15,16. Overexpression and mutation of EGFR have been associated with a more aggressive malignant phenotype, including increased resistance to treatment, and poorer clinical outcome 3,17. One reason for this overexpression is chromosomal amplification. Cytogenetic analysis of oral squamous cell carcinomas showed increased copy numbers of 7p12 (the locus for EGFR) in 30–47% of samples 18,19 and this EGFR amplification was associated with poor survival 20. In addition, truncation of the complete, wild-type EGFR gene is a common event in HNSCC, leading to a truncated 150 kDa protein lacking exons 2–7 (EGFRvIII). This in-frame deletion is within the ligand-binding domain, causing constitutive phosphorylation and activation of EGFR, independent of ligand presence 21. This constitutively active mutation is reportedly found in ~42% of HNSCC tumors, and has been shown through in vitro and mouse xenograft models to enhance tumor growth and confer resistance to EGFR-blocking antibodies 21,22. Another common alteration of EGFR in HNSCC is a variable deletion of a CA dinucleotide repeat within intron 1. This region varies from 9–21 repeats, and correlations have been made between length of repeats and decreased mRNA and protein expression 23,24.

Therapeutic approaches for interrupting EGFR signaling include monoclonal antibodies targeting the ligand binding domain of the receptor and small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) 25. The most studied monoclonal antibody is cetuximab (Erbitux™, ImClone Systems, New York, NY, USA), which received FDA approval in 2006 for the treatment of locally or regionally advanced HNSCC in combination with radiotherapy 26 , based on a phase III trial where the median duration of overall survival was 49.0 month among patients treated with combined therapy and 29.3 month among those treated with radiotherapy alone. Overall, 5-year overall survival was 45.6% in the cetuximab-plus-radiotherapy group and 36.4% in the radiotherapy-alone group. 27. However, the improvement in response rate attributable to cetuximab was primarily seen in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma, a subsite associated with Human Papilloma Virus etiology and better prognosis among HNSCCs 28. In addition, treatment of platinum-refractory recurrent or metastatic HNSCC with cetuximab as a single-agent showed response rates of 13% and disease control rates (complete response/partial response/stable disease) of 46%, which led to the FDA approval of cetuximab as a single-agent for the treatment of platinum-refractory recurrent/metastatic HNSCC 29.Thus far, no study showed that combination of cetuximab and radiation is as or more effective than concurrent cisplatin-based chemoradiation, which is currently a standard of care for locally advanced HNSCC. An ongoing multi-institutional Phase III trial comparing cisplatin-based chemoradiation with or without cetuximab will elucidate whether cetuximab combined with chemoradiation is equivalent to concurrent cisplatin-based chemoradiation.

Several tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been developed that competitively bind to the ATP pocket of EGFR leading to the inhibition of phosphorylation and the subsequent activation of the receptor’s tyrosine kinase activity 30. The most clinically advanced EGFR TKIs are gefitinib and erlotinib which both selectively and reversibly inhibit tyrosine kinase activity. Gefitinib (Iressa™, AstraZeneca, London, UK), the first of such inhibitors with oral bioavailability, has been studied as monotherapy for patients with recurrent HNSCC, with an observed response rate of 10.6% and a disease control rate of 53% 31. The median time to progression and survival were 3.4 and 8.1 months, respectively. In addition, Gefitinib has been used in combination with paclitaxel (Taxol™) and radiation in patients with local-regionally advanced HNSCC by our group, demonstrating molecular inhibition of the EGFR-AKT axis in only 1/7 on-treatment tumors sampled 32. For both, gefitinib and elotinib, combination therapies with other chemotherapeutic agents or radiation showed better results than in monotherapy 33,34,35. Recently, Hughes et al. showed that Cyp1A1 and 1A2 induction by tobacco smoking reduced erlotinib exposure in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, as steady-state trough plasma concentrations in smokers treated with 300 mg erlotinib were comparable to non-smokers at 150mg 36. As tobacco consumption is common in HNSCC patients, dose escalations of erlotinib may need to be considered in current smokers. Interestingly, resistance to EGFR inhibitors seems to be associated with over-activation of PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling 37; Gefitinib-resistant MDA-468 breast cancer cells showed increased Akt activation due to loss of PTEN, however, when PTEN was reintroduced, gefitinib treatment reduced Akt activity, induced apoptosis and promoted cell cycle delay 38. In addition, loss of PTEN might be predictive of resistance to cetuximab plus irinotecan in Colorectal Cancer 39. Further studies are needed to confirm if activation of Akt-PI3K-mTOR signaling predicts resistance to EGFR inhibitors.

2.2 Targeting PI3K

So far eight PI3K proteins have been identified and grouped into three subclasses (I–III) of which Class I is implicated to play the most important role in cancer biology 40. Class I PI3Ks are comprised of an 85-kDa regulatory subunit, which mediates receptor binding, activation and localization of the enzyme, and one of four 110-kDa catalytic subunits (α, β, δ: class IA; γ : class IB) 6. Common mutations of the PIK3CA gene, which encodes p110α, are E542K, E545K and H1047R 41. These mutations, as well as another novel mutation (Y343C) within exon 4 are found in HNSCC, with an overall mutation-rate for the PIK3CA gene in HNSCC of 11–40% 42,43,44. In addition, 3q26 copy number gain has been reported as a common and early oncogenic event in ~40–50% of HNSCC18,45, which has been correlated with transition to a more invasive phenotype 46, vascular invasion 47, and a higher probability of lymph node metastasis 45.

The two well studied first-generation PI3K inhibitors are wortmannin, a natural compound isolated from Talaromyces (Penicillium) wortmannii, and LY294002, the first synthetic drug-like small molecule inhibitor 4. While wortmannin irreversibly inhibits PI3K by forming a covalent bond with a conserved lysine residue in the ATP binding pocket of PI3K 48, LY294002 is an ATP-competitive PI3K inhibitor 49. Due to toxic side effects, poor pharmacological properties and lack of selectivity for Class I PI3K isoforms50, their application has been primarily restricted to preclinical studies.

A novel Arg-GIy-Asp-Ser-(RGDS)-conjugated LY294002 prodrug, named SF1126 (Semafore Pharmaceuticals Inc.) with favorable pharmacokinetics, has already shown both antitumor and antiangiogenic activity in preclinical studies 51 and has recently entered phase I clinical trials. In addition, the wortmannin analog, PX-866, with improved stability and decreased hepatoxicity, compared to wortmannin, exhibits significant antitumor activity in human ovarian cancer, colon cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer xenografts 52,53,54. In contrast to these pan-PI3K inhibitors, current research has already focused on developing inhibitors that preferentially target Class I isoforms. Those selective Class I PI3K inhibitors, including ZSTK474 (Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research) and XL147 (Exelixis Inc.), demonstrated potent antitumor effects in human xenograft models 55 and have recently entered clinical trials for patients with solid tumors.

2.3 Targeting PTEN Inactivation

Some reports indicate a decreased PTEN function in HNSCC due to several genetic and epigenetic alterations, including Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH), microsatellite instability (MSI), and gene inactivation by promoter hypermethylation. LOH at chromosome 10q, the chromosomal region of PTEN, has been correlated with poor prognosis in HNSCC 56. Shin et al. showed mutations within codon 222–267 of the PTEN gene in three of five samples with MSI and MSI has been reported in the 10q region in about 10–15% of HNSCC samples 57. More recently, promoter hypermethylation has been implicated in the downregulation of PTEN in HNSCC cell lines 58. These studies were carried out using 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (a known demethylating agent) to restore protein expression in cell lines lacking PTEN.

2.4 Targeting PDK1

One agent reported to inhibit PDK1 is UCN-01 (7-hydroxystaurosporine). UCN-01 was isolated from the broth of Streptomyces species N-126 59 and exhibited potent anti-tumor effects in both in vitro and in vivo tumor models 60,61,62. In addition, Amornphimoltham et al. showed that UCN-01 inhibited the AKT pathway in HNSCC cell lines 63 and the growth of HNSCC xenografts 64. Several phase I and II clinical trials have already investigated effects of UCN-01 in advanced cancer patients, both as single agent and combined with conventional chemotherapeutic agents. However, significant antitumor activities have not yet been reported 65.

Another potent drug, which may exert its cytotoxic effects through inhibition of PDK1, is topotecan. Topotecan [10-hydroxy-9-dimethylaminomethyl-(S)-camptothecin], a water-soluble camptothecin analogue, is a novel topoisomerase I inhibitor that shows activity in a number of solid tumors and hematological malignancies 66. Interestingly, Nakshio et al. showed that topotecan inhibited PDK1 kinase activity in lung cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner 67. Irinotecan, another topoisomerase I inhibitor, demonstrated single-agent activity in patients with metastatic or recurrent HNSCC 68. However, further elucidation is needed to ascertain if these effects were due to inhibition of AKT signaling.

In addition, Hsp90 inhibitors were shown to decrease Akt signaling by affecting PDK1. Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a molecular chaperone that interacts with and stabilizes many client substrates involved in modulating cell proliferation, survival, and apoptosis. When Hsp90 is inhibited, client proteins are degraded through a proteasomal-dependent pathway 69. Hsp90 inhibitors can also antagonize EGFR.

Recently, several reports documented the down-regulation of phospho-Akt and Akt signaling by HSP90 inhibitors 70,71. Fujita et al. showed that PDK1 is bound to Hsp90 via its kinase domain, thus maintaining PDK1 in a soluble and active conformational state. Hsp90 inhibitors abrogated that binding, leading to proteasomal degradation of PDK1 72. The first Hsp90 inhibitors identified were benzoquinone ansamycins (i.e., geldanamycin) isolated from fermentation broth of Streptomyces hygroscopicus 73. Preclinical evaluation of geldanamycin showed severe hepatotoxicity in animals at doses producing concntrations that were active in vitro doses 74, preventing further clinical development. Additional screening of derivatives of geldanamycin led to the identification of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG). In several animal models, 17-AAG has similar anti-tumor activity to that of geldanamycin with less toxicity 75–77. 17-AAG has entered several phase I and II clinical trials 78, 79, and has been generally well-tolerated with hepatotoxicity occurring at more aggressive dosing schedules 80. Wu et al. showed that Hsp90 is abundantly expressed in human esophageal cancer and that 17-AAG effectively inhibited cell proliferation of esophageal carcinoma cell lines and increased radiosensitivity 81. These effects of 17-AAG were correlated with its ability to downregulate signal transduction, notably in Akt-signaling 81. One limitation with 17-AAG is its poor water solubility and formulation issues, which have led to the development of 17-(Dimethylaminoethylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG) and IPI-504. Both compounds are more water soluble in comparison to 17-AAG, and have entered into clinical trials 78, 79. In 2001, Chiosis et al. 82 described the first-generation synthetic Hsp90 inhibitor, PU3, a purine-based analog with a relative binding affinity of 15–20 μM. More recently, synthetic small molecule inhibitors AUY922A 83 and SNX-2112 84 are being investigated. SNX-2112 which has a binding affinity for Hsp90 at 30 ηM, caused degradation of Hsp90 client proteins such as HER2 and Akt in the BT-474 breast cancer line in a fashion similar to that of 17-AAG. Pharmacodynamic studies with a single dose of a SNX-2112 prodrug (SNX-5422) revealed substantial decline of HER2, p-Akt, and p-Erk levels along with increased levels of cleaved PARP 84.

2.5 Targeting CK2

Casein kinase II (CK2) can activate Akt by phosphorylating Ser129 located in the linker region between the pleckstrin homolog (PH) and catalytic domains CK2 is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase that exists as a tetramer consisting of two catalytic subunits (α and α’) and two regulatory subunits (β). Although CK2 is constitutively active and located in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, elevated levels have been associated with a variety of solid tumors including HNSCC 85,86. Of note, increased CK2 activity is associated with the malignant transformation of normal mucosa to HNSCC, and furthermore, the increased activity is associated with poorer clinical outcomes in patients with HNSCC 87,88 which makes CK2 a prime candidate for targeted therapy. Although there are commercially available cell permeable CK2 inhibitors such as TBB (4,5,6,7-Tetrabromobenzotriazole) and DMAT (2-dimethylamino-4,5,6,7-tetrabromo-1H-benzimidazole), more selective inhibitors are needed for clinical investigation. One example is Emodin, an anthraquine derivative (1,3,8-trihydroxy-6-methylanthraquinone) extracted from the rhizomes of Rheum palmatum. In vitro, Emodin treatment resulted in downregulation of Akt kinase activity through dephosphorylation of the Ser473 and Thr308 residues 89. Although Emodin is as effective in inhibiting CK2 as DMAT, cells treated with DMAT did not decrease Akt phosphorylation to the extent of Emodin treatment. Further analysis showed that Emodin also directly inhibits mTOR, selectively inhibits PI3K by influencing PDK1 phosphorylation, and inhibits the phosphorylation of PTEN. A more selective CK2 inhibitor is hematein and it has been demonstrated in A548 lung cancer cells treated with this compound that CK2 kinase activity as well as Akt phosphorylation at Ser129 decrease in a dose dependent manner, ultimately leading to cell apoptosis 90.

2.6 Targeting Akt

Three isoforms of the serine-threonine kinase Akt have been described – Akt1, Akt2 and Akt3, which are encoded by the genes PKBα, PKBβ and PKBγ, respectively 6. Recent studies showed an overall increased activity of Akt signaling, including gene amplification and other alterations in HNSCC tumor specimens and cell lines, respectively 63,43,91,92. Activation of Akt is an integral step in the progression of alterations occurring in skin carcinogenesis 93. Furthermore, overexpression of Akt leads to a more aggressive phenotype with decreased apoptosis and differentiation 93. The activation status of Akt correlates well with disease progression, showing significant differences between dysplasia, carcinoma in situ and HNSCC tissue 63. As the most crucial node downstream of PI3K, Akt presents an attractive therapeutic target. A well established lipid–based Akt inhibitor is perifosine, which interacts with the pleckstrin homology domain of Akt preventing Akt from binding to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, and consequently, from activation 4. In preclinical studies, perifosine displayed potent antiproliferative activity against several in vitro and in vivo human tumor models 94, and an antiproliferative effect of perifosine in HNSCC cell lines was observed by blocking cell cycle progression at G1-S and G2-M 95. However, in a Phase II study, Perifosine lacked antitumor activity as a single agent in recurrent or metastatic HNSCC 96

2.7 Targeting mTOR

One major downstream effector of Akt is the atypical serine/threonine kinase, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which regulates cell growth by coordinating growth factor and nutrient signaling 97. Two mTOR-containing complexes have been described: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), a rapamycin-sensitive complex which interacts with the protein regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (RAPTOR); and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), a rapamycin-insensitive complex which interacts with rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR) 98, which phosphorylates Akt on Ser473 99. MTORC1 phosphorylates key eukaryotic translation regulators, including S6 kinase 1 (S6K1, also known as p70S6K) and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF-4E)-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), which plays an important role in cell growth 100. In HNSCC, eIF-4E facilitated tumor progression through the expression of angiogenic factors b-FGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) 101 and can be used as an independent predictor of recurrence in histologically “tumor-free” surgical margins of HNSCC 101.

Amornphimoltham et al. showed that the mTOR pathway plays a central role in HNSCC, as the phosphorylated active form of S6K1 is frequently accumulated in clinical specimens from HNSCC patients and in HNSCC-derived cell lines 102,103. Hence, mTOR has become an attractive target for molecular-oriented drug development. The first mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin (sirolimus; Rapamune; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), a natural product, was originally used because of its antifungal properties 104 before its immunosuppressive and, more recently, antineoplastic effects were discovered 98. Rapamycin associates with FK506-binding protein, which subsequently binds directly to mTORC1 suppressing the phosphorylation of its downstream substrates S6K1 and 4E-BP1 98. No other proteins beside mTOR have been identified as rapamycin targets, making this drug unique. Thus far, three rapamycin analogues (rapalogues) have been developed which exhibit desirable pharmacological characteristics, including oral or IV bioavailability, prolonged half-life, and reduced immunosuppressive effects compared to rapamycin. These include temsirolimus (CCI-779; Torisel, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), everolimus (RAD001, Novartis) and deforolimus (AP23573, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Merck & Co., Inc.).

In preclinical models, rapamycin and its derivates have shown antitumor activity in a variety of malignancies including HNSCC both in vitro and in vivo. Amornphimoltham et al. showed that rapamycin reduced level of activated S6 protein, a downstream effector of mTOR in HNSCC cell lines and in HNSCC xenograft models at clinically relevant doses 102. A pilot study of neoadjuvant rapamycin for evaluation of clinical and molecular activity prior to surgery has received IRB approval at the NIH.

Nathan et al. showed that CCI-779, a more water-soluble analogue of rapamycin, inhibited growth of HNSCC cell lines and xenograft models through inactivation of mTOR, as shown by decreased levels of the mTOR downstream targets S6K1 and 4E-BP1, leading to reduced production of VEGF and FGF-2 105. Preliminary reports from a phase I trial of neoadjuvant CCI-779 with radiation therapy provided evidence for tumor reduction or stabilization. In addition, Jimeno et al. studied the effect of temsirolimus alone and in combination with the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib in two HNSCC xenograft models, one resistant and the other sensitive to EGFR inhbitors 106. The growth inhibitory effect of temsirolimus monotherapy superseded erlotinib monotherapy due to abrogation of the mTOR pathway. As a negative-feedback loop exists in which S6K1 directly phosphorylates IRS1 (insulin receptor substrate protein 1) and blocks IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) signaling to PI3K 107, a major drawback of selectively inhibiting mTOR is the consequent activation of PI3K, which can ultimately enhance tumor growth 108. Thus, it is reasonable to develop compounds targeting both PI3K and mTOR. PI-103, a selective dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor showed antitumor activity in a broad range of human tumor xenografts 109, however, application of PI-103 was restricted to preclinical studies because of adverse pharmacological characteristics. Other dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors including BEZ235 (Novartis) and BGT226 (Novartis), with promising results from preclinicals studies 110, have recently entered clinical trials and may prove useful towards treatment of HNSCC.

3. Expert opinion

EGFR-PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling plays a crucial role in the tumorigenesis of various human malignancies including HNSCC. Many up- and downstream components of this pathway including EGFR, PI3K and mTOR have been shown to be highly activated in a majority of HNSCC samples, due to genetic and epigenetic alterations, which makes this pathway very attractive for molecular oriented drug therapies. While targeting EGFR has become an integral part in the therapy of HNSCC and cetuximab is used in clinical practice for HNSCC patients with locally advanced tumors and recurrent or metastatic disease, many preclinical and clinical studies are continuing to evaluate the role of other specific inhibitors of this pathway in the treatment of HNSCC patients (Table 1). Despite promising preclinical results, some of them did not show the expected effects in clinical trials, which might be due to the complexity of this pathway with multiple nodes, feedback loops, crosstalk and redundancy with other pathways. So, it seems reasonable that targeting this pathway at several points simultaneously may be more effective and may also decrease the possibility of chemotherapy resistance.

A major challenge in targeted therapies is matching the correct therapy to the patient. Hence, efforts have already been made in the search for biomarkers to identify those patients who may benefit from certain inhibitors. In several cases, patients with activated EGFR-PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling have been reported to be more sensitive to selective pathway inhibitors. Three relevant examples include: loss of PTEN, which may predict sensitivity to everolimus in patients with endometrial cancer 111; pretreatment p-AKT Ser473 and total AKT levels towards predicting response to Gefitinib treatment 32; and, EGFR CA dinucleotide repeat (based on In vitro data) towards predicting sensitivity toward erlotinib, a specific RTK inhibitor 112.

In order to evaluate the efficacy of molecular oriented therapy, it is important to develop biomarkers which can be used to verify that a specific inhibitor is reaching its desired target. Commonly used biomarkers for measuring the efficacy of PI3K inhibition are levels of phosphorylated Akt and phosphorylated S6K1. A common side effect of EGFR targeted agents, used as a correlative biomarker is a distinctive skin rash, as studies have revealed that rash severity was significantly associated with survival in HNSCC 113. Phospho-protein biomarkers for EGFR and downstream signal pathway components modulated by these inhibitors have been defined in HNSCC by immunohistochemistry and reverse phase protein microarray 32, 114.

In conclusion, future molecular oriented therapy for HNSCC should take into account the activation status of the desired target found in each individual tumor. Furthermore, the chosen agent should alter the activation of the target(s) and the altered activation should be associated with clinical benefit for the patient.

Highlights.

HNSCC is the sixth most common cancer worldwide

5 year survival rate at 50%, with little to no improvement in the last 20 years

recent studies have focused on the molecular interactions within the EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway

many genetic alterations in this pathway are found to be subsets of different oncogenic populations in HNSCC

studies have shown increased chemo- and radiosensitivity with treatment of specific genetic alterations

there are relatively few specific targets being exploited in the treatment of HNSCC, with many promising possibilities either being explored, or yet to be explored

the ultimate goal of targeted therapy is to correlate the correct course of treatment with the patient whose oncogenesis is most susceptible to therapy

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDCD Intramural Research Project ZIA-DC-000073.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

Gefitinib (Astra Zeneca) and PI3K-mTOR inhibitors (Pfizer) have been provided for research and clinical trials through material transfer and clinical trials agreements between these companies and the National Cancer Institute or National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Dr. Van Waes and the other authors declare no financial conflict of interest and have received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao L, Hong W, Papadimitrakopoulou V. Focus on head and neck cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004 Apr;5(4):311–6. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers SJ, Harrington KJ, Rhys-Evans P, O-Charoenrat P, Eccles SA. Biological significance of c-erbB family oncogenes in head and neck cancer. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2005;24(1):47–69. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts T, Zhao J. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009 Aug;8(8):627–44. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5*.Cully M, You H, Levine A, Mak T. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006 Mar;6(3):184–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc1819. This review reveals the crosstalk between PI3K pathway and othe tumorigenic signaling pathways. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6**.Vivanco I, Sawyers C. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002 Jul;2(7):489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. Excellent review on significance of PI3K signaling in cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Sarbassov D, Guertin D, Ali S, Sabatini D. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005 Feb;307(5712):1098–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. This paper demonstrated for the first time that the rictor-mTor comple directly phosphorylates Akt on Ser473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carnero A, Blanco-Aparicio C, Renner O, Link W, Leal J. The PTEN/PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in cancer, therapeutic implications. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008 May;8(3):187–98. doi: 10.2174/156800908784293659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9*.Ozes O, Mayo L, Gustin J, Pfeffer S, Pfeffer L, Donner D. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999 Sep;401(6748):82–5. doi: 10.1038/43466. This paper exhibited that Akt is involved in NF-κB activation bei TNFα. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran H, Brunet A, Griffith E, Greenberg M. The many forks in FOXO's road. Sci STKE. 2003 Mar;2003(172):RE5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.172.re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan D, Dong J, Zhang Y, Gao X. Tuberous sclerosis complex: from Drosophila to human disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2004 Feb;14(2):78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12**.Inoki K, Corradetti M, Guan K. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005 Jan;37(1):19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. A complete overview of the present dysregulations of mTor signaling described so far. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandis J, Tweardy D. Elevated levels of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor messenger RNA are early markers of carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1993 Aug;53(15):3579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thelemann A, Petti F, Griffin G, Iwata K, Hunt T, Settinari T, et al. Phosphotyrosine signaling networks in epidermal growth factor receptor overexpressing squamous carcinoma cells. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2005;4(4):356–76. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400118-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santini J, Formento JL, Francoual M, Milano G, Schneider M, Dassonville O, et al. Characterization, quantification, and potential clinical value of the epidermal growth factor receptor in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Head and Neck. 1991;13(2):132–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880130209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dassonville O, Formento J, Francoual M, Ramaioli A, Santini J, Schneider M, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor and survival in upper aerodigestive tract cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993 Oct;11(10):1873–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalyankrishna S, Grandis JR. Epidermal growth factor receptor biology in head and neck cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(17):2666–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin C, Reshmi S, Ried T, Gottberg W, Wilson J, Reddy J, et al. Chromosomal imbalances in oral squamous cell carcinoma: examination of 31 cell lines and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2008 Apr;44(4):369–82. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gollin S. Chromosomal alterations in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck: window to the biology of disease. Head Neck. 2001 Mar;23(3):238–53. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200103)23:3<238::aid-hed1025>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temam S, Kawaguchi H, El-Naggar A, Jelinek J, Tang H, Liu D, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor copy number alterations correlate with poor clinical outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun;25(16):2164–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Sok J, Coppelli F, Thomas S, Lango M, Xi S, Hunt J, et al. Mutant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRvIII) contributes to head and neck cancer growth and resistance to EGFR targeting. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Sep;12(17):5064–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0913. This study prrofs that EGFRvIII is expressed in HNSCC and contributes to enhanced growth and resistance to targeting wild-type EGFR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Loeffler-Ragg J, Schwentner I, Sprinzl G, Zwierzina H. EGFR inhibition as a therapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008 Oct;17(10):1517–31. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.10.1517. Excellent overview on current understanding of EGFR as a therapeutic target in HNSCC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Etienne-Grimaldi M, Pereira S, Magné N, Formento J, Francoual M, Fontana X, et al. Analysis of the dinucleotide repeat polymorphism in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene in head and neck cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2005 Jun;16(6):934–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki M, Kageyama S, Shinmura K, Okudela K, Bunai T, Nagura K, et al. Inverse relationship between the length of the EGFR CA repeat polymorphism in lung carcinoma and protein expression of EGFR in the carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2008 Nov;98(6):457–61. doi: 10.1002/jso.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: The complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5(5):341–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26**.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, Azarnia N, Shin DM, Cohen RB, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(6):567–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. This study led to the FDA approval for the combination of cetuximab and RT for the treatment of unresectable HNSCC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonner J, Harari P, Giralt J, Cohen R, Jones C, Sur R, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010 Jan;11(1):21–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Posner M, Wirth L. Cetuximab and radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006 Feb;354(6):634–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Vermorken J, Trigo J, Hitt R, Koralewski P, Diaz-Rubio E, Rolland F, et al. Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun;25(16):2171–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7447. This study led to the FDA approval for cetuximab as single-agent therapy for platinmum-refractory recurrent/metastatic HNSCC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. Semin Oncol. 2006 Aug;33(4):369–85. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen EEW, Rosen F, Stadler WM, Recant W, Stenson K, Huo D, et al. Phase II trial of ZD1839 in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(10):1980–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Pernas F, Allen C, Winters M, Yan B, Friedman J, Dabir B, et al. Proteomic signatures of epidermal growth factor receptor and survival signal pathways correspond to gefitinib sensitivity in head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Apr;15(7):2361–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1011. Evidence that p-Akt and p-Stat3 expression correlates with Gefitinib sensitiviy in HNSCC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soulieres D, Senzer NN, Vokes EE, Hidalgo M, Agarvala SS, Siu LL. Multicenter phase II study of erlotinib, an oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(1):77–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wirth LJ, Haddad RI, Lindeman NI, Zhao X, Lee JC, Joshi VA, et al. Phase I study of gefitinib plus celecoxib in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(28):6976–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C, Kane M, Song J, Campana J, Raben A, Hu K, et al. Phase I trial of gefitinib in combination with radiation or chemoradiation for patients with locally advanced squamous cell head and neck cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(31):4880–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes A, O'Brien M, Petty W, Chick J, Rankin E, Woll P, et al. Overcoming CYP1A1/1A2 mediated induction of metabolism by escalating erlotinib dose in current smokers. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar;27(8):1220–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Ratushny V, Astsaturov I, Burtness B, Golemis E, Silverman J. Targeting EGFR resistance networks in head and neck cancer. Cell Signal. 2009 Aug;21(8):1255–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.021. Comprehensive review on the role of EGFR as a therapeutic target in HNSCC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bianco R, Shin I, Ritter C, Yakes F, Basso A, Rosen N, et al. Loss of PTEN/MMAC1/TEP in EGF receptor-expressing tumor cells counteracts the antitumor action of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2003 May;22(18):2812–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loupakis F, Pollina L, Stasi I, Ruzzo A, Scartozzi M, Santini D, et al. PTEN expression and KRAS mutations on primary tumors and metastases in the prediction of benefit from cetuximab plus irinotecan for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jun;27(16):2622–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Domin J, Waterfield M. Using structure to define the function of phosphoinositide 3-kinase family members. FEBS Lett. 1997 Jun;410(1):91–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ligresti G, Militello L, Steelman L, Cavallaro A, Basile F, Nicoletti F, et al. PIK3CA mutations in human solid tumors: role in sensitivity to various therapeutic approaches. Cell Cycle. 2009 May;8(9):1352–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.9.8255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu W, Schönleben F, Li X, Ho D, Close L, Manolidis S, et al. PIK3CA mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Mar;12(5):1441–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia Pedrero JM, Garcia Carracedo D, Muñoz Pinto C, Herrero Zapatero A, Rodrigo JP, Suarez Nieto C, et al. Frequent genetic and biochemical alterations of the PI 3-K/AKT/PTEN pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;114(2):242–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murugan A, Hong N, Fukui Y, Munirajan A, Tsuchida N. Oncogenic mutations of the PIK3CA gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2008 Jan;32(1):101–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fenic I, Steger K, Gruber C, Arens C, Woenckhaus J. Analysis of PIK3CA and Akt/protein kinase B in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2007 Jul;18(1):253–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woenckhaus J, Steger K, Werner E, Fenic I, Gamerdinger U, Dreyer T, et al. Genomic gain of PIK3CA and increased expression of p110alpha are associated with progression of dysplasia into invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol. 2002 Nov;198(3):335–42. doi: 10.1002/path.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Estilo C, O-Charoenrat P, Ngai I, Patel S, Reddy P, Dao S, et al. The role of novel oncogenessquamous cell carcinoma-related oncogene and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110alpha in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Clin Cancer Res. 2003 Jun;9(6):2300–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wymann M, Bulgarelli-Leva G, Zvelebil M, Pirola L, Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield M, et al. Wortmannin inactivates phosphoinositide 3-kinase by covalent modification of Lys-802, a residue involved in the phosphate transfer reaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996 Apr;16(4):1722–33. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knight Z, Gonzalez B, Feldman M, Zunder E, Goldenberg D, Williams O, et al. A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110alpha in insulin signaling. Cell. 2006 May;125(4):733–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)- 8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(7):5241–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garlich J, De P, Dey N, Su J, Peng X, Miller A, et al. A vascular targeted pan phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor prodrug, SF1126, with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Cancer Res. 2008 Jan;68(1):206–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howes A, Chiang G, Lang E, Ho C, Powis G, Vuori K, et al. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor, PX-866, is a potent inhibitor of cancer cell motility and growth in three-dimensional cultures. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007 Sep;6(9):2505–14. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ihle N, Williams R, Chow S, Chew W, Berggren M, Paine-Murrieta G, et al. Molecular pharmacology and antitumor activity of PX-866, a novel inhibitor of phosphoinositide-3-kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004 Jul;3(7):763–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ihle N, Paine-Murrieta G, Berggren M, Baker A, Tate W, Wipf P, et al. The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibitor PX-866 overcomes resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor gefitinib in A-549 human non-small cell lung cancer xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005 Sep;4(9):1349–57. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yaguchi S, Fukui Y, Koshimizu I, Yoshimi H, Matsuno T, Gouda H, et al. Antitumor activity of ZSTK474, a new phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Apr;98(8):545–56. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gasparotto D, Vukosavljevic T, Piccinin S, Barzan L, Sulfaro S, Armellin M, et al. Loss of heterozygosity at 10q in tumors of the upper respiratory tract is associated with poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 1999 Aug;84(4):432–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990820)84:4<432::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Field J, Kiaris H, Howard P, Vaughan E, Spandidos D, Jones A. Microsatellite instability in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Br J Cancer. 1995 May;71(5):1065–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurasawa Y, Shiiba M, Nakamura M, Fushimi K, Ishigami T, Bukawa H, et al. PTEN expression and methylation status in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2008 Jun;19(6):1429–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi I, Saitoh Y, Yoshida M, Sano H, Nakano H, Morimoto M, et al. UCN-01 and UCN-02, new selective inhibitors of protein kinase C. II. Purification, physico-chemical properties, structural determination and biological activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1989 Apr;42(4):571–6. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akinaga S, Gomi K, Morimoto M, Tamaoki T, Okabe M. Antitumor activity of UCN-01, a selective inhibitor of protein kinase C, in murine and human tumor models. Cancer Res. 1991 Sep;51(18):4888–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seynaeve C, Stetler-Stevenson M, Sebers S, Kaur G, Sausville E, Worland P. Cell cycle arrest and growth inhibition by the protein kinase antagonist UCN-01 in human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1993 May;53(9):2081–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Sato S, Fujita N, Tsuruo T. Interference with PDK1-Akt survival signaling pathway by UCN-01 (7-hydroxystaurosporine) Oncogene. 2002 Mar;21(11):1727–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205225. This study provides evidence that UCN-01 directly inhibit PDK1 upstream of Akt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amornphimoltham P, Sriuranpong V, Patel V, Benavides F, Conti CJ, Sauk J, et al. Persistent activation of the Akt pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A potential target for UCN-01. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(12 I):4029–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel V, Lahusen T, Leethanakul C, Igishi T, Kremer M, Quintanilla-Martinez L, et al. Antitumor activity of UCN-01 in carcinomas of the head and neck is associated with altered expression of cyclin D3 and p27KIP1. Clinical Cancer Research. 2002;8(11):3549–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Welch S, Hirte H, Carey M, Hotte S, Tsao M, Brown S, et al. UCN-01 in combination with topotecan in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer: a study of the Princess Margaret Hospital Phase II consortium. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Aug;106(2):305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rothenberg M. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: review and update. Ann Oncol. 1997 Sep;8(9):837–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1008270717294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakashio A, Fujita N, Rokudai S, Sato S, Tsuruo T. Prevention of phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase-Akt survival signaling pathway during topotecan-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2000 Sep;60(18):5303–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murphy B. Topoisomerases in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent squamous carcinoma of the head and neck. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005 Jan;6(1):85–92. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whitesell L, Mimnaugh EG, De Costa B, Myers CE, Neckers LM. Inhibition of heat shock protein HSP90-pp60v-src heteroprotein complex formation by benzoquinone ansamycins: essential role for stress proteins in oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Aug 30;91(18):8324–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hostein I, Robertson D, DiStefano F, Workman P, Clarke P. Inhibition of signal transduction by the Hsp90 inhibitor 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin results in cytostasis and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2001 May;61(10):4003–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nimmanapalli R, O'Bryan E, Bhalla K. Geldanamycin and its analogue 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin lowers Bcr-Abl levels and induces apoptosis and differentiation of Bcr-Abl-positive human leukemic blasts. Cancer Res. 2001 Mar;61(5):1799–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fujita N, Sato S, Ishida A, Tsuruo T. Involvement of Hsp90 in signaling and stability of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002 Mar;277(12):10346–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DeBoer C, Meulman PA, Wnuk RJ, Peterson DH. Geldanamycin, a new antibiotic. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1970 Sep;23(9):442–7. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.23.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Supko JG, Hickman RL, Grever MR, Malspeis L. Preclinical pharmacologic evaluation of geldanamycin as an antitumor agent. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;36(4):305–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00689048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kelland LR, Sharp SY, Rogers PM, Myers TG, Workman P. DT-Diaphorase expression and tumor cell sensitivity to 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin, an inhibitor of heat shock protein 90. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Nov 17;91(22):1940–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Banerji U, Walton M, Raynaud F, Grimshaw R, Kelland L, Valenti M, et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for the heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitor 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in human ovarian cancer xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Oct 1;11(19 Pt 1):7023–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schulte TW, Neckers LM. The benzoquinone ansamycin 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin binds to HSP90 and shares important biologic activities with geldanamycin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42(4):273–9. doi: 10.1007/s002800050817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78**.Banerji U. Heat shock protein 90 as a drug target: some like it hot. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Jan 1;15(1):9–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0132. An excellent overview on HSP90 as a potent target in cancef theapie. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim HL, Cassone M, Otvos L, Jr, Vogiatzi P. HIF-1alpha and STAT3 client proteins interacting with the cancer chaperone Hsp90: therapeutic considerations. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008 Jan;7(1):10–4. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.1.5458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sausville EA, Tomaszewski JE, Ivy P. Clinical development of 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2003 Oct;3(5):377–83. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu X, Wanders A, Wardega P, Tinge B, Gedda L, Bergstrom S, et al. Hsp90 is expressed and represents a therapeutic target in human oesophageal cancer using the inhibitor 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin. Br J Cancer. 2009 Jan;100(2):334–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chiosis G, Timaul MN, Lucas B, Munster PN, Zheng FF, Sepp-Lorenzino L, et al. A small molecule designed to bind to the adenine nucleotide pocket of Hsp90 causes Her2 degradation and the growth arrest and differentiation of breast cancer cells. Chem Biol. 2001 Mar;8(3):289–99. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eccles SA, Massey A, Raynaud FI, Sharp SY, Box G, Valenti M, et al. NVP-AUY922: a novel heat shock protein 90 inhibitor active against xenograft tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2008 Apr 15;68(8):2850–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Ye Q, Scott A, Silinski M, Huang K, et al. SNX2112, a synthetic heat shock protein 90 inhibitor, has potent antitumor activity against HER kinase-dependent cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Jan 1;14(1):240–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gapany M, Faust RA, Tawfic S, Davis A, Adams GL, Ahmed K. Association of elevated protein kinase CK2 activity with aggressive behavior of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Mol Med. 1995 Sep;1(6):659–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Faust RA, Gapany M, Tristani P, Davis A, Adams GL, Ahmed K. Elevated protein kinase CK2 activity in chromatin of head and neck tumors: association with malignant transformation. Cancer Lett. 1996 Mar 19;101(1):31–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(96)04110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Faust RA, Tawfic S, Davis AT, Bubash LA, Ahmed K. Antisense oligonucleotides against protein kinase CK2-alpha inhibit growth of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in vitro. Head Neck. 2000 Jul;22(4):341–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200007)22:4<341::aid-hed5>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guerra B, Issinger OG. Protein kinase CK2 in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(19):1870–86. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olsen BB, Bjorling-Poulsen M, Guerra B. Emodin negatively affects the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT signalling pathway: a study on its mechanism of action. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(1):227–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hung MS, Xu Z, Lin YC, Mao JH, Yang CT, Chang PJ, et al. Identification of hematein as a novel inhibitor of protein kinase CK2 from a natural product library. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mandal M, Younes M, Swan EA, Jasser SA, Doan D, Yigitbasi O, et al. The Akt inhibitor KP372–1 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and anoikis in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncology. 2006;42(4):430–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Segrelles C, Moral M, Fernanda Lara M, Ruiz S, Santos M, Leis H, et al. Molecular determinants of Akt-induced keratinocyte transformation. Oncogene. 2006;25(8):1174–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Perez P, Murga C, Santos M, Budunova IV, et al. Functional roles of Akt signaling in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21(1):53–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hideshima T, Catley L, Yasui H, Ishitsuka K, Raje N, Mitsiades C, et al. Perifosine, an oral bioactive novel alkylphospholipid, inhibits Akt and induces in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006 May;107(10):4053–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Patel V, Lahusen T, Sy T, Sausville E, Gutkind J, Senderowicz A. Perifosine, a novel alkylphospholipid, induces p21(WAF1) expression in squamous carcinoma cells through a p53-independent pathway, leading to loss in cyclin-dependent kinase activity and cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 2002 Mar;62(5):1401–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Argiris A, Cohen E, Karrison T, Esparaz B, Mauer A, Ansari R, et al. A phase II trial of perifosine, an oral alkylphospholipid, in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006 Jul;5(7):766–70. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shamji A, Nghiem P, Schreiber S. Integration of growth factor and nutrient signaling: implications for cancer biology. Mol Cell. 2003 Aug;12(2):271–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98**.Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E. Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006 Aug;5(8):671–88. doi: 10.1038/nrd2062. Excellent review on mTor inhibitors in Cancer therapy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307(5712):1098–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004 Aug;18(16):1926–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nathan C, Franklin S, Abreo F, Nassar R, De Benedetti A, Glass J. Analysis of surgical margins with the molecular marker eIF4E: a prognostic factor in patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Sep;17(9):2909–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Amornphimoltham P, Patel V, Sodhi A, Nikitakis NG, Sauk JJ, Sausville EA, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin, a molecular target in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Research. 2005;65(21):9953–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Clark C, Shah S, Herman-Ferdinandez L, Ekshyyan O, Abreo F, Rong X, et al. Teasing out the best molecular marker in the AKT/mTOR pathway in head and neck squamous cell cancer patients. Laryngoscope. 2010 Jun;120(6):1159–65. doi: 10.1002/lary.20917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vézina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal S. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975 Oct;28(10):721–6. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nathan CAO, Amirghahari N, Rong X, Giordano T, Sibley D, Nordberg M, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors as possible adjuvant therapy for microscopic residual disease in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Cancer Research. 2007;67(5):2160–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jimeno A, Kulesza P, Wheelhouse J, Chan A, Zhang X, Kincaid E, et al. Dual EGFR and mTOR targeting in squamous cell carcinoma models, and development of early markers of efficacy. British Journal of Cancer. 2007;96(6):952–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Huang J, Manning B. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009 Feb;37(Pt 1):217–22. doi: 10.1042/BST0370217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Research. 2006;66(3):1500–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Raynaud F, Eccles S, Clarke P, Hayes A, Nutley B, Alix S, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of a potent inhibitor of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases. Cancer Res. 2007 Jun;67(12):5840–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Maira S, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, Furet P, Schnell C, Fritsch C, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008 Jul;7(7):1851–63. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Slomovitz BM, Lu KH, Johnston T, Munsell M, Ramondetta LM, Broaddus RR, et al. A phase II study of oral mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, RAD001 (everolimus), in patients with recurrent endometrial carcinoma (EC) J Clin Oncol. 2008 May 20;26(suppl):abstr 5502. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Amador M, Oppenheimer D, Perea S, Maitra A, Cusatis G, Cusati G, et al. An epidermal growth factor receptor intron 1 polymorphism mediates response to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2004 Dec;64(24):9139–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pérez-Soler R. Can rash associated with HER1/EGFR inhibition be used as a marker of treatment outcome? Oncology (Williston Park) 2003 Nov;17(11 Suppl 12):23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Van Waes C, Allen CT, Citrin D, Gius D, Colevas AD, Harold NA, et al. Molecular and clinical responses in a pilot study of gefitinib with paclitaxel and radiation in locally advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Jun 1;77(2):447–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wirth L, Haddad R, Lindeman N, Zhao X, Lee J, Joshi V, et al. Phase I study of gefitinib plus celecoxib in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct;23(28):6976–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen C, Kane M, Song J, Campana J, Raben A, Hu K, et al. Phase I trial of gefitinib in combination with radiation or chemoradiation for patients with locally advanced squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Nov;25(31):4880–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]