Abstract

Variations in maternal care alter the developmental programming of some genes by creating lasting differences in DNA methylation patterns, such as the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) promoter region. Interestingly, mother rats preferentially lick and groom their male offspring more than females; therefore, we questioned whether the somatosensory stimuli associated with maternal grooming influences potential sex differences in DNA methylation patterns within the developing amygdala, an area important for socioemotional processing. We report a sex difference in the DNA methylation pattern of specific CpG sites of the ERα promoter region within the developing amygdala. Specifically, males have higher levels of ERα promoter methylation contrasted to females. Increasing the levels of maternal stimuli in females masculinized ERα promoter methylation patterns to male-like levels. As expected, higher levels of ERα promoter methylation were associated with lower ERα mRNA levels. These data provide further evidence that the early neonatal environment, particularly maternal care, contributes to sex differences and early programming of the neonatal brain via an epigenetic mechanism.

Keywords: Epigenetic, Maternal care, Sexual differentiation, Methylation, Estrogen receptor alpha, Amygdala, RT-PCR, Brain, Development

1. Introduction

Variations in early-life experience are known to produce lasting differences in gene expression, brain development, and ultimately changes in behavior (Szyf and Meaney, 2008). Epigenetic mechanisms, such as changes in DNA methylation patterns, have been shown to be modulated by differences in maternal care (Weaver et al., 2005). For example, it was shown that the amount of licking and grooming received by neonatal female rats created lasting modifications in DNA methylation patterns on the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) promoter region and corresponding changes in ERα expression within the hypothalamus (Champagne et al., 2006; Kurian et al., 2010). Therefore, variations in maternal stimuli alter the developmental programming of some genes during the neonatal period within brain regions important for reproductive behavior.

In light of the fact that ERα can be influenced by aspects of maternal care (Champagne et al., 2006; Kurian et al., 2010), it is important to recognize that ERα plays a significant role in sex differences within the brain. Many of the effects of testosterone on brain development are thought to occur through its aromatization to estradiol and subsequent binding to estrogen receptors (ERs, MacLusky and Naftolin, 1981). ERalpha (ERα) seems to be the dominant estrogen receptor during development where it plays a critical role in sexual differentiation (Kudwa et al., 2006). The organizational effects of estrogen include altering synaptic connections, cell number, neuronal survival, and neuronal migration (for review, see Simerly, 2002). These organizational effects last into adulthood and contribute to many of the behavioral and physiological differences between the sexes.

Since ERα promoter methylation is developmentally programmed by the amount of maternal care experienced, as well as by sex hormones (Kurian et al., 2010), it is important to note that mother rats will preferentially lick and groom their male offspring more than their female offspring (Moore and Morelli, 1979). Therefore, not only is there a difference in hormone levels between the sexes (Rhoda et al., 1984; Weisz and Ward, 1980), but also in the amount of maternal grooming experienced by male versus female rat pups. We recently investigated whether altering the somatosensory stimulation associated with licking and grooming would influence sex differences in ERα expression within the developing rat preoptic area. Indeed, giving neonatal females more simulated maternal grooming (SMG) resulted in male-typical expression of ERα mRNA and methylation patterns of the exon 1b ERα promoter region (Kurian et al., 2010). These data suggest that natural variations in maternal stimuli between the sexes further refine the epigenetic patterning of ERα expression and thereby sexual differentiation of the brain.

While it is clear that maternal stimuli can program ERα expression in brain regions important for adult reproductive behavior, it is not known if maternal stimuli alter DNA methylation programming of ERα expression with the developing amygdala. As the amygdala is important for social and emotional processing, the amygdala is a critical part of the neural network necessary for regulating a variety of behaviors in mammals. In fact, a recent study demonstrated that knockdown of ERα within the amygdala resulted in decreased social recognition and decreased anxiety-like behavior (Spiteri et al., 2010). Therefore, we examined whether somatosensory stimulation associated with licking and grooming alters ERα promoter methylation patterns in both males and females within the developing amygdala.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

2.1.1. General care

Adult Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories Inc., Wilmington, MA) were kept in our animal facility on a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. Adult female rats were mated and allowed to deliver normally. Cages were checked regularly to determine the day of birth. The day in which pups were born before 10 am was considered postnatal day 0 (P0). Each experimental group included animals from at least four litters and animals from each litter were mixed and then distributed equally among groups. Litters were culled to no more than 12 pups. On P0, one foot from each pup was tattooed with a small amount of India ink for identification purposes. This research was approved by the University of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1.2. Simulated maternal grooming (SMG) paradigm

Pups received simulated maternal grooming (SMG) or control handling three times per day, one in the light cycle and two in the dark cycle, until the day of sacrifice. During treatment, pups were removed from the dam immediately prior to treatment, kept under a warming lamp and on a warm heating pad while away from the dam, and immediately returned to the dam following treatment. SMG consisted of 3 rounds of 10 strokes to the anogenital region with a soft nylon-bristled brush. Control pups were handled in the same manner but did not receive stimulation from the paintbrush.

2.2. Tissue collection

Animals were sacrificed via rapid decapitation 2 h after the second round of SMG/control handling on either postnatal day 2 (P2) or postnatal day 10 (P10). On P2, group sizes consisted of 10 control females, 9 SMG females, 8 control males, and 11 SMG males. On P10, group sizes consisted of 7 control females, 9 SMG females, 11 control males, and 12 SMG males. The amygdala was microdissected with razor blades and immediately frozen in isopentane on dry ice. To dissect the amygdala, the whole brain was placed ventral side up on a cold surface. Using a razor blade, two coronal cuts, one caudal to the optic chiasm and one caudal to the hypothalamus, were made. Then, this section of tissue was placed rostral side up and a cut was made along the optic tract followed by another cut at approximately 60 deg to form an approximate triangle. Both sides of the amygdala were collected, pooled, and frozen. The tissue was stored at −80 °C until homogenization.

2.3. Quantification of DNA methylation

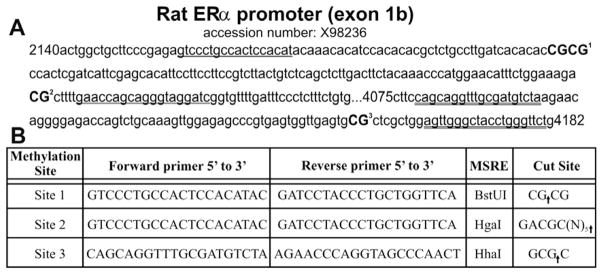

Genomic DNA was isolated using Qiagen’s AllPrep Mini Kit (Cat. #80204, Valencia, CA). DNA concentrations were determined using the Qubit Quantification Platform (Cat. #Q32857, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). We followed a previously published two-step method used to determine the quantification of the percent of cells that display methylation at a specific CpG site (Hashimoto et al., 2007). Samples of DNA were digested using one of three methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (MSRE); BSTUI, HgaI, or HhaI. In each case, control DNA received identical treatment, except without the enzyme. BSTUI (Cat. #R0518S, New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) recognizes CGCG sites and cleaves DNA between the G and the C if that C is not methylated (Fig. 1). To examine the methylation status of CpG sites sensitive to BSTUI cleavage, each sample was divided equally into two tubes which were incubated with either BSTUI enzyme or a control no enzyme solution for 1 h at 60 °C. Immediately following incubation, the BSTUI enzyme was extracted from the DNA using a GenElute Mammalian Genomic DNA Kit (Cat. #G1N350, Sigma). HgaI (Cat. #R0154, New England BioLabs) recognizes the sequence GACGC and cleaves five nucleotides downstream of the recognition site if the CG is not methylated (Fig. 1). HhaI (Cat. #R0139, New England BioLabs) recognizes GCGC sequences and cleaves the C away from GCG if the CG is not methylated (Fig. 1). To examine the methylation status of CpG sites sensitive to either HgaI or HhaI cleavage, each sample was divided equally into two tubes which were incubated with either MSRE enzyme (i.e., HgaI or HhaI) or a control no enzyme solution for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by 20 min at 65 °C to inactivate the enzyme.

Fig. 1.

Methodological details for CpG sites analyzed within the exon 1b ERα promoter. (A) Sequence for the portion of the exon 1b ERα promoter region (GenBank Accession No. X98236) examined. Primer annealing sequences used for examining methylation at site 1 and site 2 is underlined with a single line. Primer annealing sequences used for examining methylation at site 3 is double underlined. Each methylation site examined is bolded and numbered. (B) Forward and reverse primer sequences are shown that were used to investigate the methylation status of the three sites using a methyl-sensitive restriction enzyme (MSRE). The same primers were used for examining methylation at site 1 or site 2. The nucleotide sequence cut site for each MSRE is indicated by an arrow. Methylation at these CpG sites protects against enzyme digestion and allows for PCR amplification.

After the enzyme digest, the amount of amplification of each DNA sample was examined using real-time PCR performed in a Stratagene Mx3000P™ Real-Time PCR system. DNA was amplified using Sybr® Green I (S7563, Invitrogen), GoTaq Colorless Master Mix (Cat. #M7132, Promega, Madison, WI), and ROX as a reference dye (Cat. #12223012, Invitrogen). SYBR® Green emits fluorescence as it intercalates into double strand DNA (dsDNA). The sequence examined was the exon 1b ERα promoter region (GenBank Accession No. X98236). See Fig. 1 for the primers used for each CpG site examined. To note, one sample per group was removed from methylation analysis due to DNA processing error. All primer and sample concentrations were optimized to ensure efficiencies of near 100%. Real-time PCR data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Specifically, the ΔΔCT for each sample was determined by calculating the difference between the average CT of the reference sample (non-enzyme digested sample) and the average CT of the sample of interest (enzyme digested sample). The ΔCT of the internal calibrator, which has the lowest CT count, is subtracted from the ΔCT of each sample to determine the ΔΔCT. This value is then used to determine the amount of methylated DNA relative to the calibrator using the equation 2−ΔΔCT.

2.4. Quantification of mRNA

Total RNA was isolated along with genomic DNA from snap-frozen tissue using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Cat. #80004, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA concentrations were determined using the Qubit Quantification Platform (Cat. #Q32857, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and cDNA was generated with ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (Cat. #A3800, Promega) according to manufacturer recommendations in an Eppendorf MasterCycler Personal PCR machine. Samples were stored at −80 °C. Real-time RT-PCR was conducted with a Stratagene Mx3000P™ real-time PCR system. cDNA was amplified using Sybr® Green I (S7563, Invitrogen), GoTaq Colorless Master Mix (Cat. #M7132, Promega), and ROX as a reference dye (Cat. #12223012, Invitrogen). The amplification protocol is as follows: an initial melting step at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of a 95 °C melting step for 30 s, a 60 °C annealing step for 30 s, and a 72 °C elongation step for 30 s. The primer sequences for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) mRNA are 5′–3′ as follows: Forward – TCCGGCACATGAGTAACAAA, Reverse – TGAAGACGATGAGCATCCAG. The primer sequences for the housekeeping gene, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1) mRNA are 5′–3′ as follows: Forward – GCAGACTTTGCTTTCCTTGG, Reverse – CCGCTGTCTTTTAGGCTTTG. These mRNA primers were synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Recent publications indicate that HPRT1 might be one of the best broad application qPCR housekeeping genes, especially when considering genes that could be influenced by hormones (Bonefeld et al., 2008; Filby and Tyler, 2007; de Kok et al., 2004). To date, we have not observed sex differences in HPRT1 expression in any region, treatment, or time point in any of our studies. Primer and sample concentrations were optimized to ensure efficiencies of near 100%. Following amplification, a dissociation melt curve analysis was performed to ensure the purity and identity of PCR products. Data were analyzed with the following program term settings based on invitrogen recommendations: (1) amplified based threshold, (2) adaptive baseline set v1.00 to v3.00 algorithm and (3) smoothing moving average with amplification averaging three points. Relative cDNA levels were calculated using the ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Samples were normalized to HPRT1.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made between the four treatment groups using a two-way analysis of variance using SigmaPlot v11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). All post hoc tests were conducted using Student–Newman–Keuls (SNK).

3. Results

3.1. Variations in maternal stimuli alter the DNA methylation patterns of some CpG sites within the ERα promoter region in a sex and time dependent manner

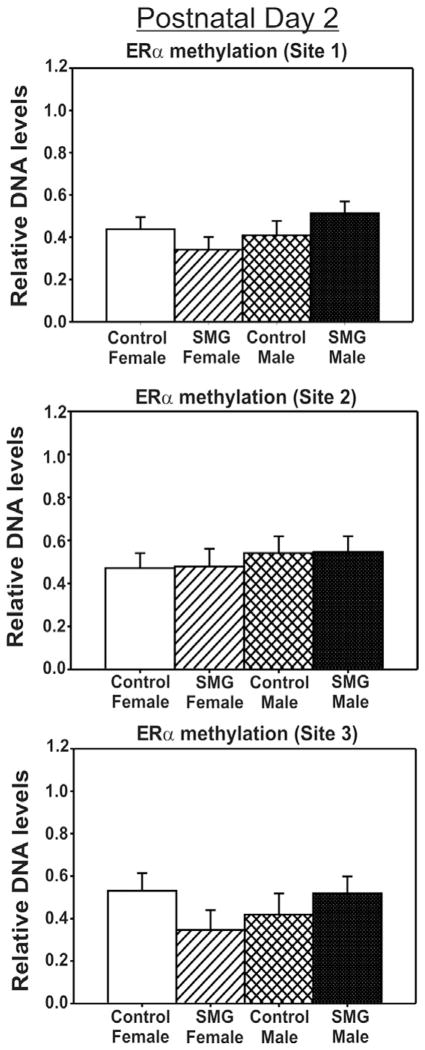

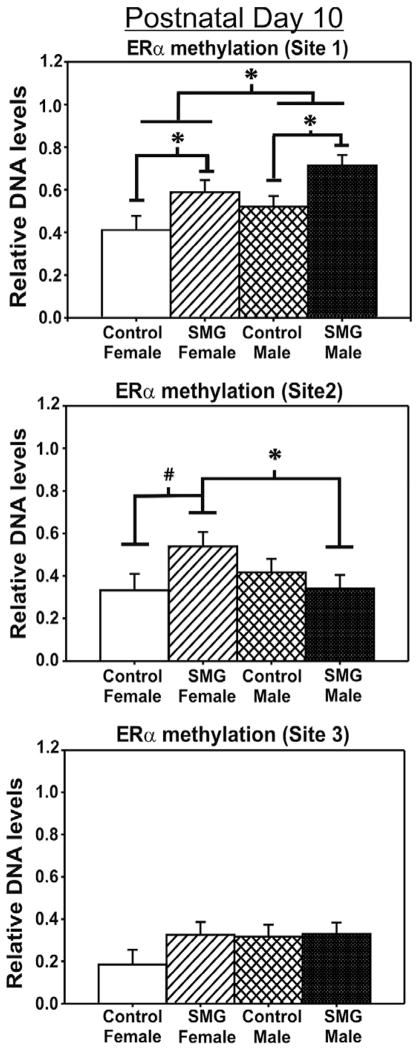

To examine if maternal stimuli alters DNA methylation patterns within the ERα promoter region within the developing amygdala, we examined the impact of SMG in both males and females at two time points. To do this, we examined methylation patterns at three CpG sites within the exon 1b ERα promoter region on postnatal days 2 and 10. The first and second CpG sites are near the consensus signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 5 binding region that has been shown to regulate ERα transcription. The third CpG site is over a 1000 bp downstream (Fig. 1). At P2, no significant difference of sex or SMG were apparent at any of the CpG sites investigated (p > 0.05, Fig. 2). However, by P10, there is both an effect of sex and group. Specifically, at the first CpG site investigated, males had significantly more methylation than females (F(1, 31) = 4.46, p < 0.05, Fig. 3). There was also an overall effect of SMG, where rats given more somatosensory stimuli had more methylation than rats given control handling (F(1, 31) = 11.11, p < 0.01, Fig. 3). At the second CpG site, there was a significant interaction of sex by group (F(1, 28) = 4.27, p < 0.05, Fig. 3). Post hoc analysis using Student–Newman–Keuls revealed that SMG females had significantly more methylation than SMG males (p < 0.05). SMG females appeared to have higher levels of methylation than control females, but this did not reach statistical significance (Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc, p = 0.055, Fig. 3). Importantly, there were no significant differences found at the third CpG site that is located over a 1000 bases away from the STAT5 binding site (p > 0.05, Fig. 3), suggesting a level of specificity of altered methylation patterns induced by SMG.

Fig. 2.

ERα promoter methylation is not altered by simulated maternal grooming or sex on P2. No significant differences in CpG methylation were found at either of the CpG sites examined (p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

ERα promoter methylation is altered by simulated maternal grooming and sex on P10. At site1, there is a sex difference in methylation where males have more methylation than females (*p < 0.05). Additionally, SMG-treated females have significantly more methylation than control-handled females (*p < 0.05) and are not statistically different than males. Interestingly, SMG also altered DNA methylation in males. At site 2, SMG-treated females had significantly more methylation than SMG-treated males (*p < 0.05). A strong trend towards SMG females having more methylation than control females was observed (#p = 0.055). There were no significant differences found at the third CpG site (p > 0.05).

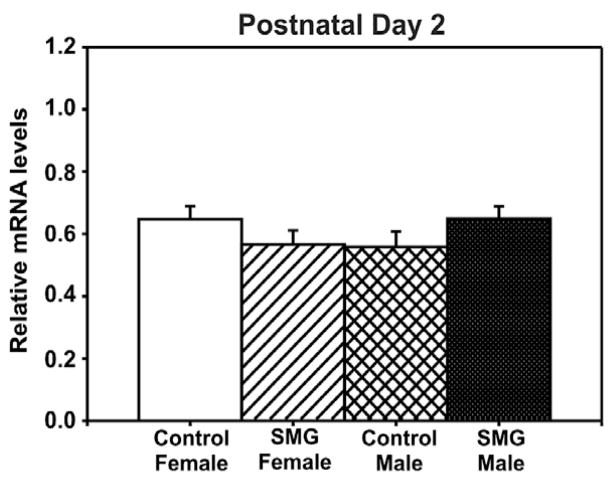

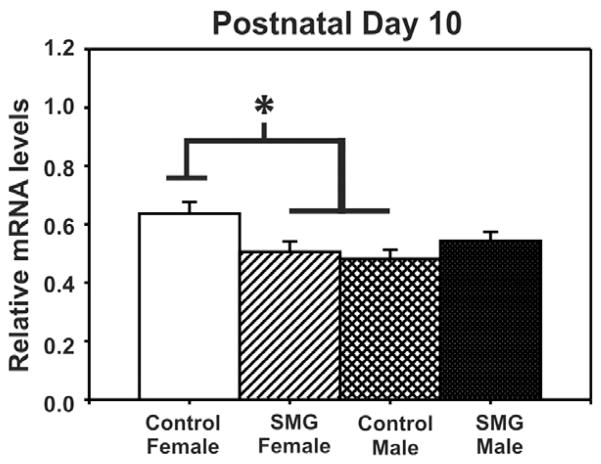

To examine whether the methylation patterns of these CpG sites are associated with gene expression, we also examined mRNA in the same samples. Consistent with the lack of changes in ERα promoter methylation at P2, no significant difference of sex or SMG was found in ERα mRNA levels at this time point (p > 0.05, Fig. 4). In contrast, changes in mRNA levels were observed by P10 that inversely corresponded with the changes in ERα promoter methylation. Specifically, there was a significant interaction of sex by group (F(1, 34) = 7.44, p = 0.01, Fig. 5). Post hoc analysis using Student–Newman–Keuls revealed that control males and SMG females had significantly lower ERα mRNA expression than control females (p < 0.01, <0.05, respectively). This expression pattern is consistent with the idea that methylation of some CpG sites is associated with gene repression.

Fig. 4.

ERα mRNA levels are not altered by simulated maternal grooming or sex on P2. No significant difference in ERα mRNA levels was observed (p > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

ERα mRNA levels are altered by simulated maternal grooming and sex on P10. Control females expressed more ERα mRNA than SMG-treated females (*p < 0.05) or control males (*p < 0.01). There is no statistical difference between SMG-treated females and males.

4. Discussion

We report that variations in somatosensory stimuli associated with maternal grooming during the neonatal period can modify sex differences in DNA methylation patterns of the ERα promoter within the developing amygdala. As neonatal males receive more maternal grooming than females (Moore and Morelli, 1979), we examined the consequences of increased maternal stimuli on ERα promoter methylation and mRNA expression. Intriguingly, we found that sex differences in DNA promoter methylation and ERα gene expression is modulated by the neonatal environment, as SMG influenced both expression and methylation patterns. That is, providing females with more somatosensory stimulation associated with maternal grooming resulted in male-typical patterns of ERα mRNA levels and methylation of certain CpG sites in the exon 1b ERα promoter region within the developing amygdala. As the amygdala is important for numerous socioemotional behaviors, these data suggest that differences in mother–infant interactions may program lasting changes in gene expression that impact social or emotional processes that occur within the amygdala. These data also suggest that somatosensory stimuli associated with maternal care may further refine sex differences in the brain via an epigenetic mechanism.

To the best of our knowledge, no other studies have examined ERalpha promoter methylation within the amygdala. Sex differences in DNA methylation in the ERalpha promoter have been examined in the preoptic area (Champagne et al., 2006; Kurian et al., 2010; Schwarz et al., 2010), the mediobasal hypothalamus (Schwarz et al., 2010), and the isocortex (Westberry et al., 2010).

A study by Kuhnemann et al. examined estrogen receptors in the amygdala and preoptic area for sex differences using in vitro autoradiographic analysis of estrogen binding (Kuhnemann et al., 1994). While sex differences were found in the hypothalamus, there was only a strong trend for more estrogen binding in females than males on postnatal day 10 within the amygdala. Therefore, it is possible that sex differences in ERalpha expression is more robust in the preoptic area compared to the amygdala.

While previous literature has demonstrated that gonadal hormones are responsible for shaping many sex differences in the brain, the current study lends support to the growing literature indicating that the environment can also play a critical role in sexual differentiation (Auger et al., 2010). Mechanisms for sexual differentiation of the brain now extend to ligand-independent activation of steroid receptors (Olesen et al., 2005), chromosomal contributions (De Vries et al., 2002), and brain synthesis of neurosteroids (Amateau et al., 2004). As SMG programming of sex differences in the developing amygdala appear to occur independent of changes in gonadal hormones (Kurian et al., 2010), this suggests that maternal behavior is an additional factor that can modify sexual differentiation of the brain. The functional significance of an environmental stimuli (like SMG) altering sex differences remains unclear, but this may serve to prepare the offspring for the type of environment it will encounter as an adult. For example, adult offspring that received more licking and grooming performed better during a low-stress condition and worse in a high-stress environment compared to offspring that received less licking and grooming (Champagne et al., 2008). This implies that the amount of maternal care an offspring receives may convey information about the environment to the offspring during the sensitive period of brain development. This information may shape neural networks in order to allow the offspring to perform more efficiently under specific environmental situations by altering reproductive function, social interactions, and anxiety-like behavior later in life.

The precise meaning of methylation at specific CpG sites is unclear; however, it seems like the importance of the methylation status of a CpG site in some cases correlates with its proximity to binding sites of key regulatory factors. In the current study, the two CpG sites that were sensitive to sex and environment are near the consensus STAT5b binding site (TTCTAGGAA, Galsgaard et al., 1999). As STAT5b has been shown to stimulate ERα transcription using this binding sequence (Frasor and Gibori, 2003), methylation of this STAT5b binding site within the ERα promoter region may decrease ERα gene expression. Indeed, a previous study reported that more methylation within this consensus STAT5 binding site was associated with decreased STAT5 binding and decreased ERalpha expression within the medial preoptic area of the brain (Champagne et al., 2006). In the current study, we found that increased methylation at two CpG sites near this STAT5 binding region was associated with decreased ERα mRNA levels within the amygdala. Taken together, methylation at these CpG sites may alter ERα mRNA levels by regulating key regulatory factors, such as this STAT5 binding sequence. Although the third CpG site was over a 1000 bp downstream of this STAT5 binding sequence, it was near another STAT5 site (TTCAGGGAA, Barclay et al., 2011). However, it is unclear whether this particular STAT5 binding sequence is important for regulating estrogen receptor alpha levels within the brain. In the current study, no significant difference in methylation status at the third CpG site was found.

The differences in ERα methylation and expression found in this study seem to be established between P2 and P10, as no difference was apparent by P2. The fact that methylation patterns had not yet been influenced by sex or SMG at P2 is intriguing. Although further research is needed to fully elucidate the reason behind this time-course, this result could be suggestive of a few things. It may indicate a critical threshold in the amount of environmental stimulus received. Perhaps a chronic stimulus (i.e., many days of altered maternal care) is required to adjust DNA methylation patterns, suggesting that programming of ERα is tightly regulated during development. On the other hand, the time-course could be indicative of the time required to change the expression of regulatory factors that alter DNA methylation (e.g., DNMTs) or the time needed to accumulate enough methyl marks for a difference in cell population to be accurately measured. Finally, the methylation patterns at P2 and P10 may be a result of sensitivity to SMG manipulation. Neonatal rats demonstrate characteristic responses to somatosensory stimuli to the anogenital region, including leg extension and suckling behavior (Moore and Chadwick-Dias, 1986). While conducting SMG, it appears that although leg extension is displayed from P0 to P10, the response to SMG peaks around P4–P5. Therefore, the time-course of methylation at the ERα promoter region may correlate with the peak response to SMG.

The current study indicates that maternal stimuli can modify sex differences and gene expression within the developing amygdala, a brain region known to be critical for juvenile social interactions, in particular social play behavior (Auger and Olesen, 2009; Meaney, 1989). Recent data have shown that variations in maternal care can alter play fighting behavior in male rats (Parent and Meaney, 2008). Taken together, these data lend support to the idea that the somatosensory stimuli associated with maternal care may alter the developmental programming of the amygdala and result in modified social interactions.

The early maternal environment has been shown to have profound effects on the offspring. Manipulating the early environment can alter the development of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, maintenance of the stress hypo-responsive period, and immune function (Groer et al., 2002; Levine, 2000; Liu et al., 1997; Shanks and Lightman, 2001). Importantly, postnatal somato-sensory stimulation seems to inhibit many of the brain-related changes that occur as a result of maternal separation, including the rise of adrenocorticotropic hormone and the reduction of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH, Levine, 2002; van Oers et al., 1998). As estrogens have been shown to increase CRH levels within the amygdala (Jasnow et al., 2006), and our manipulation alters the availability of estrogen receptors, it is likely that maternal stimulation also alters adult stress responses via its actions on estrogen receptor levels. Additionally, a recent study demonstrated that knockdown of ERα within the amygdala resulted in decreased social recognition and decreased anxiety-like behavior (Spiteri et al., 2010). Therefore, tactile stimulation may alter socioemotional function and stress effects on immune response via epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression.

In summary, these data indicate that variations in maternal stimuli are an additional mechanism regulating sexual differentiation of the amygdala. Specifically, somatosensory stimuli associated with maternal grooming can alter DNA methylation patterns of certain CpG sites in the ERα promoter resulting in changes in ERα mRNA levels. This suggests that early-life experiences impact epigenetic programming of steroid responsive genes in the developing amygdala that may ultimately lead to lasting differences in social, emotional, or physiological processes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01MH072956 and the University of Wisconsin Neuroscience Training Program Grant T32 GM007507. We also like to thank Dr. Kris Olesen, Dr. Nina Hasen, and Heather Jessen.

References

- Amateau SK, Alt JJ, Stamps CL, McCarthy MM. Brain estradiol content in newborn rats: sex differences, regional heterogeneity, and possible de novo synthesis by the female telencephalon. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2906–2917. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger AP, Jessen HM, Edelmann MN. Epigenetic organization of brain sex differences and juvenile social play behavior. Horm Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.06.017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger AP, Olesen KM. Brain sex differences and the organisation of juvenile social play behaviour. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:519–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay JL, Nelson CN, Ishikawa M, Murray LA, Kerr LM, McPhee TR, Powell EE, Waters MJ. GH-dependent STAT5 signaling plays an important role in hepatic lipid metabolism. Endocrinology. 2011;152:181–192. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonefeld BE, Elfving B, Wegener G. Reference genes for normalization: a study of rat brain tissue. Synapse. 2008;62:302–309. doi: 10.1002/syn.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne DL, Bagot RC, van Hasselt F, Ramakers G, Meaney MJ, de Kloet ER, Joels M, Krugers H. Maternal care and hippocampal plasticity: evidence for experience-dependent structural plasticity, altered synaptic functioning, and differential responsiveness to glucocorticoids and stress. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6037–6045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0526-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Weaver IC, Diorio J, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2909–2915. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kok JB, Roelofs RW, Giesendorf BA, Pennings JL, Waas ET, Feuth T, Swinkels DW, Span PN. Normalization of gene expression measurements in tumor tissues: comparison of 13 endogenous control genes. Lab Invest. 2004;85:154–159. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries GJ, Rissman EF, Simerly RB, Yang LY, Scordalakes EM, Auger CJ, Swain A, Lovell-Badge R, Burgoyne PS, Arnold AP. A model system for study of sex chromosome effects on sexually dimorphic neural and behavioral traits. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9005–9014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09005.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filby A, Tyler C. Appropriate ’housekeeping’ genes for use in expression profiling the effects of environmental estrogens in fish. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasor J, Gibori G. Prolactin regulation of estrogen receptor expression. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:118–123. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galsgaard ED, Nielsen JH, Moldrup A. Regulation of prolactin receptor (PRLR) gene expression in insulin-producing cells, Prolactin and growth hormone activate one of the rat prlr gene promoters via STAT5a and STAT5b. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18686–18692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groer MW, Hill J, Wilkinson JE, Stuart A. Effects of separation and separation with supplemental stroking in BALb/c infant mice. Biol Res Nurs. 2002;3:119–131. doi: 10.1177/1099800402003003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Kokubun S, Itoi E, Roach HI. Improved quantification of DNA methylation using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes and real-time PCR. Epigenetics. 2007;2:86–91. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.2.4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasnow AM, Schulkin J, Pfaff DW. Estrogen facilitates fear conditioning and increases corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA expression in the central amygdala in female mice. Horm Behav. 2006;49:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudwa AE, Michopoulos V, Gatewood JD, Rissman EF. Roles of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in differentiation of mouse sexual behavior. Neuroscience. 2006;138:921–928. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnemann S, Brown TJ, Hochberg RB, MacLusky NJ. Sex differences in the development of estrogen receptors in the rat brain. Horm Behav. 1994;28:483–491. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, Olesen KM, Auger AP. Sex differences in epigenetic regulation of the estrogen receptor-{alpha} promoter within the developing preoptic area. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2297–2305. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Influence of psychological variables on the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;405:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in the neonatal rat: the role of maternal behavior. Neurotox Res. 2002;4:557–564. doi: 10.1080/10298420290030569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal responses to stress. Science. 1997;277:1659–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-[Delta][Delta]CT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, Naftolin F. Sexual differentiation of the central nervous system. Science. 1981;211:1294–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.6163211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. The sexual differentiation of social play. Psychiatr Dev. 1989;7:247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CL, Chadwick-Dias AM. Behavioral responses of infant rats to maternal licking: variations with age and sex. Dev Psychobiol. 1986;19:427–438. doi: 10.1002/dev.420190504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CL, Morelli GA. Mother rats interact differently with male and female offspring. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1979;93:677–684. doi: 10.1037/h0077599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen KM, Jessen HM, Auger CJ, Auger AP. Dopaminergic activation of estrogen receptors in neonatal brain alters progestin receptor expression and juvenile social play behavior. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3705–3712. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent CI, Meaney MJ. The influence of natural variations in maternal care on play fighting in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 2008;50:767–776. doi: 10.1002/dev.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoda J, Corbier P, Roffi J. Gonadal steroid concentrations in serum and hypothalamus of the rat at birth: aromatization of testosterone to 17 beta-estradiol. Endocrinology. 1984;114:1754–1760. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-5-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Nugent BM, McCarthy MM. Developmental and hormone-induced epigenetic changes to estrogen and progesterone receptor genes in brain are dynamic across the life span. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4871–4881. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks N, Lightman SL. The maternal–neonatal neuro-immune interface: are there long-term implications for inflammatory or stress-related disease? J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1567–1573. doi: 10.1172/JCI14592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB. Wired for reproduction: organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiteri T, Musatov S, Ogawa S, Ribeiro A, Pfaff DW, Agmo A. The role of the estrogen receptor alpha in the medial amygdala and ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in social recognition, anxiety and aggression. Behav Brain Res. 2010;210:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetics, behaviour, and health. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4:37–49. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-4-1-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oers HJ, De Kloet ER, Whelan T, Levine S. Maternal deprivation effect on the infant’s neural stress markers is reversed by tactile stimulation and feeding but not by suppressing corticosterone. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10171–10179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-10171.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver ICG, Champagne FA, Brown SE, Dymov S, Sharma S, Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Reversal of maternal programming of stress responses in adult offspring through methyl supplementation: altering epigenetic marking later in life. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11045–11054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J, Ward IL. Plasma testosterone and progesterone titers of pregnant rats, their male and female fetuses, and neonatal offspring. Endocrinology. 1980;106:306–316. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-1-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberry JM, Trout AL, Wilson ME. Epigenetic regulation of estrogen receptor alpha gene expression in the mouse cortex during early postnatal development. Endocrinology. 2010;151:731–740. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]