Abstract

Background

The standard clinical approach for reducing cardiovascular disease risk due to dyslipidemia is to prescribe changes in diet and physical activity. The purpose of the current study was to determine if, across a range of dietary patterns, there were variable lipoprotein responses to an aerobic exercise training intervention.

Methods

Subjects were participants in the Studies of a Targeted Risk Reduction Intervention through Defined Exercise (STRRIDE I), a supervised exercise program in sedentary, overweight subjects randomized to 6 months of inactivity or one of 3 aerobic exercise programs. To characterize diet patterns observed during the study, we calculated a modified z-score that included intakes of total fat, saturated fat, trans fatty acids, cholesterol, omega-3 fatty acids and fiber as compared to the 2006 AHA diet recommendations. Linear models were used to evaluate relationships between diet patterns and exercise effects on lipoproteins/lipids.

Results

Independent of diet, exercise had beneficial effects on LDL-cholesterol particle number, LDL-cholesterol size, HDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol size, and triglycerides (P<0.05 for all). However, having a diet pattern that closely adhered to AHA recommendations was not related to changes in these or any other serum lipids or lipoproteins in any of the exercise groups.

Conclusions

We found that even in sedentary individuals whose habitual diets vary in the extent of adherence to AHA dietary recommendations, a rigorous, supervised exercise intervention can achieve significant beneficial lipid effects.

Lifestyle factors, including diet and exercise, are well recognized as important modifiable determinants of risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and are often the first to be recommended in the outpatient setting. Plasma levels of lipids linked with elevated (LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides) and reduced (HDL-cholesterol) CVD risk are known to be responsive to changes in both diet and physical activity level. Thus, clinical advice for individuals with dyslipidemia typically includes two oft-repeated recommendations: (1) adopt a lipid-lowering diet pattern and (2) increase the level of physical activity. In reality, these goals are not uniformly applied or achieved. Some clinicians may choose to emphasize one treatment option more than the other or may be better at explaining one modality versus the other. Patients also differ in their likelihood of achieving these recommendations. Some may be more successful at modifying their diet patterns while others encounter fewer barriers to instituting a regular exercise program.

Important advantages could result from a better understanding of diet and exercise interactions, permitting clinicians to target lifestyle recommendations to achieve the therapeutic goal while minimizing the behavioral burden on the patient. Yet, few clinical studies have carefully examined the interaction of diet intake patterns with the effects of exercise on lipid-related CVD risk. In many exercise studies, detailed diet data are simply not collected and/or diet instructions are lacking or non-specific.1 Further, the intentional combination of diet and exercise interventions often obscures individual effects.2

Using data from the first Studies of a Targeted Risk Reduction Intervention through Defined Exercise (STRRIDE I: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00200993) trial, we sought to determine the influence of diet patterns on lipid responses to a supervised exercise intervention targeting CVD risk. As previously described 3, the treatment groups were low amount /moderate intensity (L/M), low amount /vigorous intensity (L/V) and high amount/vigorous intensity (H/V) aerobic exercise training. All STRRIDE I subjects were instructed not to change their baseline diet composition and body mass during the trial. Diet records were carefully and consistently collected during the intervention and analyzed for nutrient composition, enabling us to explore the interaction of diet with lipid changes. We hypothesized that diet pattern effects would be small or absent in the H/V group but that diet patterns would be more influential on lipid outcomes in the L/M and L/V groups.

A secondary aim in this study was to find results applicable for clinical use by characterizing the diets by pattern, rather than considering each nutrient individually. Thus, we derived a single diet pattern z-score that characterized the degree to which the diet of each STRRIDE I subject conformed to recommendations from the American Heart Association (AHA) for CVD risk reduction. We then examined the influence of these diet pattern z-scores on lipid responses to exercise.

Methods

Funding

This work was supported by the NHLBI (NIH) R01HL-57354 and NIH/NIAMS K23AR054904.

Subjects and Experimental Design

STRRIDE I study design, hypotheses, recruitment strategies, methods, preliminary results, and the initial findings for exercise effects on serum lipids are published elsewhere 3,4Written, informed consent was obtained from all subjects. In this analysis, we report on the 204 subjects for whom full nutrition and lipid information was available. There were no significant differences (P<0.05 for all) in age, gender, race, or BMI between the subjects not included (n=23) and thoseindividuals included in this analysis.

The study group came from a population at high risk of developing CVD. Recruited from Durham and Greenville, North Carolina and surrounding communities, subjects were inactive men and women (postmenopausal by self-report)aged 40 to 65 years, were overweight or mildly obese (BMI 25 to 35 kg/m2) and had mild to moderate lipid abnormalities (either LDL-cholesterol 130 to 190 mg/dl or HDL-cholesterol < 40 mg/dl for men, or < 45 mg/dl for women). .

Institution of the Intervention and Measurement of Outcomes

Exercise training

Participants were randomly assigned, with blocking by gender, race, and study site, to either a six month non-exercising control group (C) or one of the three exercise training groups: 1) H/V, the caloric-equivalent of approximately 20 miles per week for a 90 kilogram person at 65 to 80% peak-VO2; 2) L/V, approximately 12 miles per week at 65 to 80% peak-VO2; and 3) L/M, approximately 12 miles per week at 40 to 55% peak-VO2. For H/V, the specific prescription was to expend 23 kilocalories per kilogram body weight per week; the prescription was 14 kilocalories per kilogram per week for L/V and L/M. There was an initial ramp period of two to three months to allow subjects to adapt to their exercise prescription, followed by six additional months of training at the appropriate exercise prescription. Exercise compliance was carefully monitored by direct supervision and the use of downloadable heart rate monitors (Polar Electro, Inc; Woodbury, NY).

Dietary Assessment

At the beginning of the trial, participants were trained on techniques for accurately reporting food characteristics and portion size estimations. Participants recorded all foods and beverages consumed over three days, including one weekend day in a 3-day diet record (3-DDR). Dietary records are often used as a standard for the validation of other diet assessment methods; they provide quantitatively precise information on foods consumed during a specific recording period. Participants were also interviewed in person or by telephone and asked to recall all foods/beverages consumed for an unannounced 24-hour time period (24-HrDR). The interviewer utilized a modified 5-step pass method; during the initial pass, the participant was asked to give an uninterrupted list of the foods consumed during the designated period. Next, the interviewer asked probing questions to elicit commonly forgotten foods, then inquired about the time and occasion of each eating occurrence, and then about the exact amount of foods eaten. Lastly, a review of the foods eaten was completed to prompt any forgotten eating occasions or foods. The multiple pass approach restricts under-reporting by providing repeated memory cues and opportunities to recall and report food intake. Food Processor Nutrition Analysis Software (Version 7.1, 1996, ESHA Research, Salem, OR) was utilized to analyze the information gathered from the 3-day records (3-DDR) and 24-hour recalls (24-HrDR). Using data from the initial 3-DDR and 24-HrDR, a nutritionist generated an initial dietary profile, and subjects were counseled to maintain this diet composition for the trial duration. Dietary data (24-HrDR and 3-DDR) were also collected at three additional points, the end of the ramp period (exercisers only), mid-intervention (3 months of control or training), and post-intervention (6 months of control or training). Based on 24-HrDR and 3-DDR results, an average intake for each dietary component (e.g., saturated fat, trans fat, etc.) was computed for each participant at each time point and over the course of the trial; these average intakes were then used in the diet pattern analysis as described in the next section.

Characterization of Diet Patterns with Respect to AHA Recommendations

Rather than the effects of individual diet components, we wished to investigate the overall impact of diet intake patterns on lipoprotein/lipid responses. Table 1 illustrates how we compared diet intake results to the respective 2006 AHA Diet and Lifestyle Recommendations for total, saturated, and trans fat, cholesterol, omega 3 fatty acids and fiber by calculating a modified z-score 6–8. While not applicable at the time the diet data were collected in this study, the AHA has recently released new recommendations for lipid-related diet components.9 The recommendations are the same for fat, saturated fat, trans fat, and omega-3 fatty acids, and high fiber intakes continue to be encouraged; the cholesterol recommendation is now <150 mg/day, reduced from <300 mg/day.10

Table I.

Scoring Criteria for “AHA-Type” Diet Z-Score, Values for STRIDE Subjects by Diet Parameter, and Comparison to National Survey Findings

| Diet Parameter | AHA* | Std. for z- score |

Sample Median |

Range | Inter- quartile Range |

Typical Population Intake† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat, % of kcal | 25–35 | 30 | 33.8 | 11.9– 56.3 |

30.7–37.0 | 32.7 |

| Saturated fat (% kcal) |

<7 | 7 | 11.6 | 2.1–19.4 | 9.9–13.0 | 11.2 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | <300 | 300 | 273 | 25–1123 | 211.0–360.4 | 265 |

| Trans fat (g) | <2.2† | 1‡ | 1.9 | 0–15.0 | 1.2–3.3 | 5.3 |

| Omega-3 FA (g/d) | 0.5 to 1.8 g§ | 1.6, 1.1 |

0.8, 0.8 |

0.2–4.2 | 0.6–1.2, 0.6–1.1 |

1.44 |

| Soluble Fiber (g/d) | 5–10 | 7.5 | 2.8 | 0.5–8.2 | 2.1–3.7 | 2.4 |

AHA: American Heart Association diet recommendations, 2006.

Obtained from NHANES III adult population, 1999–2000 (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/, accessed 10 February 2008); for trans fat, from the CS FII survey23(1989–1991); and, for soluble fiber, from the NHANES Follow-up study,24 expressed per 1735 kcal.

The AHA recommendation is that less than 1% of kcal come from trans fat, which for a 2000 kcal diet translates to about 2.2 grams/day. However, at the time of this analysis, food data bases were very incomplete for trans fat and yet food content of trans fat was reasonably high. Therefore we used an arbitrary standard of 1 g or less of trans fat per day as the standard for our z score calculations.

The AHA recommends an intake of 0.5 to 1.8 grams per day of EPA plus DHA 7 In order to have a specific quantity for comparison, we used the Adequate Intake (AI) recommended by the Institute of Medicine, Dietary Reference Intakes, 2005, for men and women, respectively and listed results separately.

Z-scores were created for each dietary item as follows: Diet item value for an individual – AHA ideal value)/study population standard deviation and (for items where lower reported concentrations were considered deleterious) AHA ideal value – individual’s diet item value)/study population standard deviation. Because of the AHA recommendations for omega-3 fatty acids differ by gender, separate scores were computed for men and women. For each individual, a composite diet z-score was derived as the average of the z scores for each of the six diet constituents:

Diet Z scorewomen = [((Fat % kcal - 30)/5.8753) + ((Saturated Fat % kcal - 7)/2.6286) + ((Cholesterol mg - 300)/127.58) + ((Trans fat daily grams - 1)/2.0504) + ((1.1 - Omega-3 FA daily grams)/0.5423) + ((7.5 - Soluble fiber daily grams)/1.3524)]/6

Diet Z scoremen = [((Fat % kcal - 30)/5.8753) + ((Saturated Fat % kcal - 7)/2.6286) + ((Cholesterol mg -300)/127.58) + ((Trans fat daily grams - 1)/2.0504) + ((1.6 - Omega-3 FA daily grams)/0.5423) + ((7.5 - Soluble fiber daily grams)/1.3524)]/6

Statistical Methods

Mixed models were used to determine whether diet z scores changed significantly over time while controlling for age, gender, intervention group, and the repeated effect of time. Change scores were calculated for all lipid variables by subtracting pre-training values from post-training values. Linear models were used to evaluate the effects of diet pattern (as represented by the overall diet z-score), exercise, and the interaction between diet pattern and exercise on lipoproteins/lipids. Specifically, we examined the main effect of diet (the impact of diet on lipids, after taking into account exercise, and assuming that this impact is the same for each of the exercise groups) and the main effect of exercise (the impact of exercise on lipids, after taking into account diet, and assuming that this impact is the same regardless of diet). We then used the diet-by-exercise interaction to quantify the degree to which the impact of diet on lipids depended on the exercise group to which subjects were assigned. Full models with interaction terms (diet z-score*exercise group) were initially evaluated. If the interaction term was not significant, it was removed and the model was refit. Statistical significance was established at P<0.05, except for interaction terms where P<0.10 was considered signficant.. All analyses were adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and baseline lipoprotein level. Statistics were performed with Enterprise guide 4.1 (SAS, Cary, NC).

Results

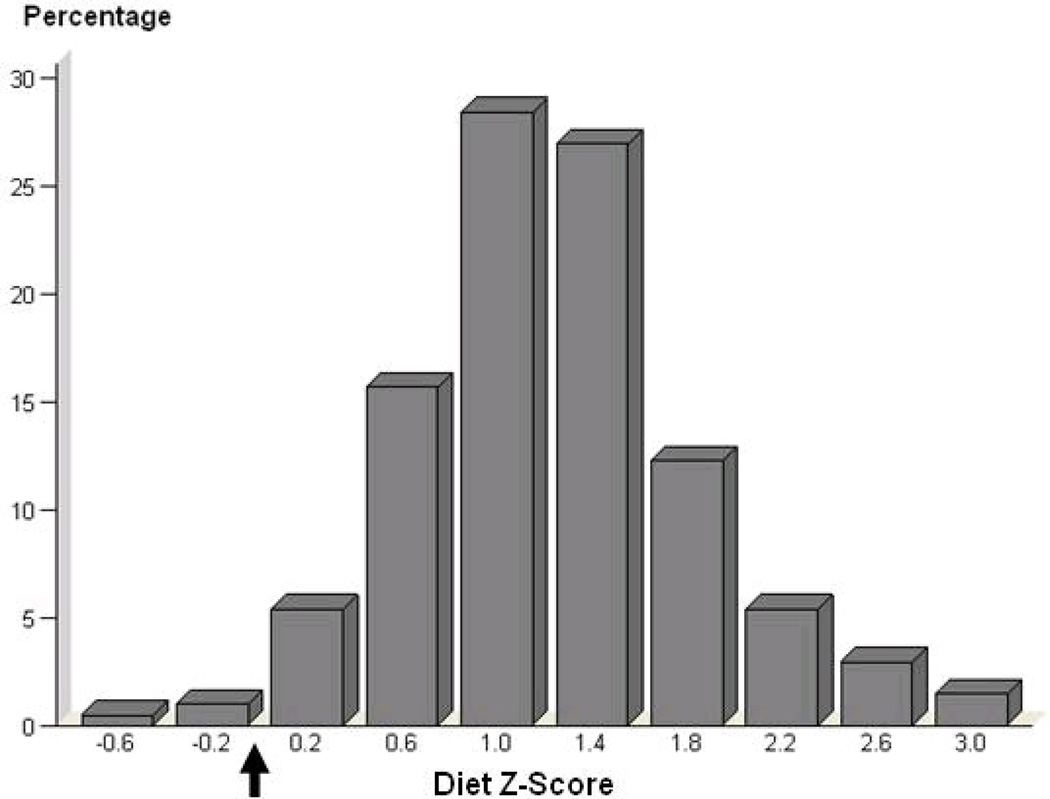

Median intakes of the target nutrients were similar to those reported in representative national studies (Table II). Intakes of fat and saturated fat tended to exceed, and intakes of omega-3 fatty acids and fiber fall to short of, recommended standards. Diet patterns (Diet z scores) and reported calorie intakes [2009 (± 433), 2029 (± 481), 2012 (± 497), and 2119 (± 519) kcal for the control, L/M, L/V, and H/V groups, respectively] did not vary significantly between treatment groups (P=0.61, P=0.64, respectively) or over the course of the trial (P=0.52, P=0.28, respectively), which permitted us to calculate a single average diet pattern Z score for each individual. As illustrated in Figure 1, most diet pattern z-scores deviated from the ideal AHA recommended diet score of zero. There was considerable variability in diet z-scores between participants (−0.65 to 3.11), providing power for evaluations over a wide range of diets. Over the 9 month study period, relative to the control group that had a slight increase in body weight (mean ± SD change of 0.8 ± 2.5 kg), body weights of subjects in the treatment groups decreased significantly, although the effect sizes were modest (L/M: −0.7 ± 2.4 kg, L/V: −0.6 ± 2.1 kg, and H/V: −1.9 ± 2.7 kg; P<0.05 for all).

Table II.

Baseline values, change scores, and diet (AHA diet pattern) effects for LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides

| Control | Low Amount/Moderate | Low Amount/Vigorous | High Amount/Vigorous | Exercise and Diet Effects |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=51) | (n=46) | (n=52) | (n=55) |

Grou p effect P- value |

Diet effect P- value |

Diet X group P- value |

|||||

| Variable | Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | |||

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 123.4 (106.3– 141) |

4.7±18.9 | 128.65 (109.50– 143.00) |

0.0±18.8 | 128.5 (113.6– 146.0) |

1.3±16.5 | 122 (111–143) |

−0.5±18.7 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.73 |

|

Concentration LDL- C particles (nmol/L) |

1385 (1158– 1615) |

92.4±288.5 | 1349.15 (1222.00– 1538.30) |

−0.1±225.8 | 1381.5 (1183.5– 1571.3) |

−1.6±202.0 | 1319 (1194– 1518) |

−49.2±260.1 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.86 |

| LDL-C size (nm) | 21.0 (20.3–21.4) |

−0.1±0.5 | 21.0 (20.4–21.6) |

0.1±0.4 | 21.1 (20.5–21.6) |

0.1±0.4 | 21.1 (19.8–21.5) |

0.2±0.4 | 0.009 | 0.19 | 0.68 |

|

Concentration small LDL-C (mg/dl) |

10.0 (0.0–37.7) |

6.7±33.7 | 9.3 (0.0–35.9) |

1.9±22.5 | 5.9 (0.0–33.9) |

−0.4±17.9 | 15.7 (0.0–52.3) |

−5.5±23.0 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.39 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 42.3 (34.9–53.0) |

0.2±6.1 | 44.2 (37.7–54.7) |

0.1±5.1 | 41.8 (36.0–53.5) |

1.3±5.7 | 41.0 (34.0–51.3) |

3.2±6.8 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.69 |

| HDL-C size (nm) | 8.8 (8.5–9.1) |

0.0±0.3 | 8.85 (8.60–9.00) |

0.1±0.2 | 8.8 (8.7–9.2) |

0.0±0.2 | 8.8 (8.6–9.0) |

0.1±0.2 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.88 |

|

Concentration large HDL-C particles (mg/dl) |

24.7 (16.9–34.7) |

0.7±7.2 | 24.85 (18.30– 36.60) |

−0.5±6.6 | 26.5 (14.7–35.3) |

1.0±6.9 | 23.3 (14.7–33.4) |

3.2±7.6 | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.86 |

| IDL-C (mg/dl) | 0 (0–6) |

0.0±3.5 | 0 (0–6) |

−1.2±4.5 | 0.0 (0.0–4.1) |

−0.3±3.8 | 0.2 (0.0–7.4) |

−2.3±4.2 | 0.07 | 0.58 | 0.44 |

|

Triglycerides (mg/dl) |

118.9 (94.1–194) |

4.9±48.6 | 141.9 (108.0– 199.0) |

−39.9±71.8 | 126 (89–182) |

−8.2±51.0 | 131.8 (92.0– 206.0) |

−23.7±45.7 | 0.002 | 0.64 | 0.94 |

HDL= high density lipoprotein; LDL= low density lipoprotein; IDL= intermediate density lipoprotein

Change is mean absolute change between baseline and study end, ± SD.

Full models were performed, and interaction terms from full models are displayed above. Interaction terms were removed and main effects models were rerun; group and diet effects displayed above represent those from main effects models. All analyses were adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and baseline lipoprotein level.

Figure 1. Distribution of Diet Z-Scores in STRRIDE.

Black arrow denotes the z-score for an ideal American Heart Association diet.

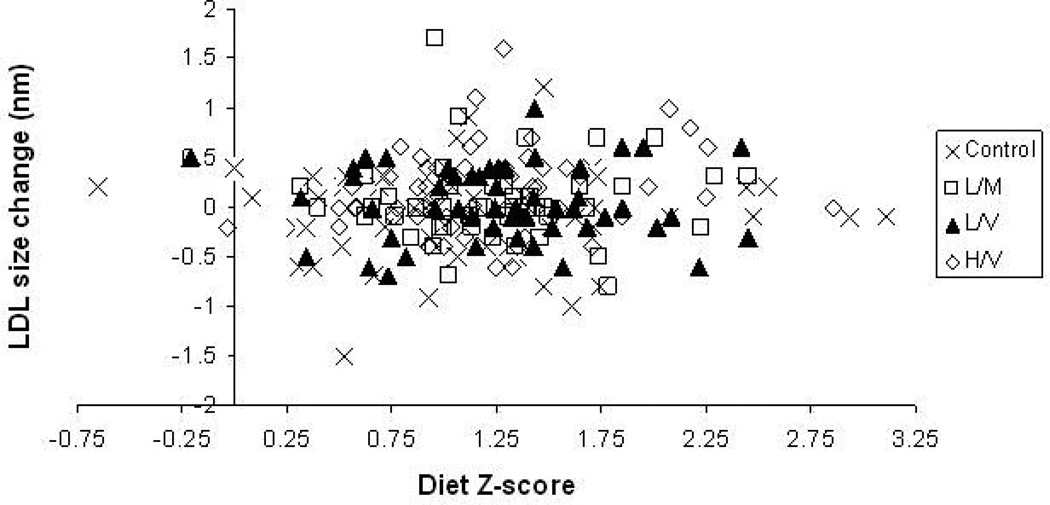

Table 2 provides the baseline values, change scores, group (exercise treatment) effects, and diet pattern effects for fasting plasma lipids and lipoproteins. Independent of diet z-score, beneficial group (exercise) effects were seen for the concentration and average size of LDL particles (P=0.03; P=0.009 ), concentration of HDL-cholesterol (P=0.03), average size of HDL particles (P=0.05), and triglycerides (P<0.001). Trends towards significant exercise group effects were also seen for concentration of large HDL-cholesterol (P=0.06) and IDL-cholesterol (P=0.07). However, no influence of dietary intakes with respect to AHA recommendations was observed for these or any other of the lipid components. Likewise, the diet by group analysis showed that there was no interaction of diet z-scores with the responses of any of these lipids to exercise (P>0.10 for all). As an example, Figure 2 depicts the lack of main diet z-score effect or of a diet z-score*group interaction on LDL particle size change during the six month intervention.

Figure 2. Relationship between Diet Z-Score and Low Density Lipoprotein Particle Size Change by STRRIDE Exercise Group.

Control/Inactive group is represented by cross-hairs; Low-Amount Moderate-Intensity represented by open squares; Low-Amount Vigorous Intensity represented by filled triangles; and, High-Amount Vigorous-Intensity represented by open diamonds.

Discussion

As previously published from STRRIDE I findings, we observed that an aerobic exercise intervention, in the absence of clinically significant weight loss, improves lipoprotein profiles.4 Here, we extend these findings by reporting that exercise-mediated improvements in lipoprotein profiles are independent of the extent to which participants adhered to an AHA recommended diet pattern. Our findings suggest that when an exercise regimen is instituted to improve lipoprotein profiles, at least within the range of diet patterns evaluated in this study, diet composition does not need to be modified in order to achieve beneficial lipid responses to exercise training in previously overweight, sedentary middle-aged individuals.

Our findings do not in any way undermine the importance of diet as a determinant of CVD risk. A comprehensive body of literature has already established that, individually, the dietary components we studied can influence CVD outcomes. In particular, the impact of dietary fat intakes on CVD risk is well characterized. Accordingly, an extensive body of evidence supports a positive linear relationship of dietary saturated fat, as well as cholesterol intake, with levels of serum total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) and CVD risk. Also, a high predominance of trans fatty acids can adversely affect both LDL- and HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) and increase the risk of developing CVD While evidence for the effects of dietary omega-3 fatty acids is more preliminary than for other fats, current findings from epidemiologic and clinical trials links intakes in the range of 0.53 to 2.8g/day with decreased risk of CVD.8 The lipids-modifying and beneficial cardiovascular effects of consuming generous amounts of dietary fiber are also well-recognized.

In contrast to the strong body of literature on diet components considered individually, few prospective studies have examined the combined impact of these factors on changes in CVD risk factors such as lipoprotein profiles. This is unfortunate since, for “real world” applicability, it is important to consider the impact of the diet in total. Nutrients and foods are not eaten in isolation but in complex combinations that can be interactive or synergistic. Diet cluster analysis is one method recently used to examine relationships between nutrient intake patterns and future health outcomes.15 For example, Millen et al. linked a heart-healthy dietary pattern with lower odds of subclinical heart disease in 1,423 women in the Framingham Offspring Study as examined at the 12-yr follow-up.16 This confirms similar findings in women from the Nurses’ Health Study17 and in men from the prospective Professional Health cohort study.18 While these large population studies allow for sophisticated statistical analyses of diet patterns, they are limited by the fact that the diet information usually comes from a single food frequency questionnaire. Multiple measures of dietary intake and assessments to characterize dietary patterns over time in the context of well-controlled, randomized clinical trials are needed to evaluate cause and effect relationships. In one of few such studies, Lichtenstein et al. examined the efficacy of the TLC/Step 2 diet in 36 moderately hypercholesterolemic subjects.19 These investigators fed a controlled diet providing 30% of kcal from fat and 75 mg cholesterol per 1000 kcal. This diet produced changes in some (e.g., LDL-C, HDL-C) and but not in all (e.g., triglycerides, TC: HDL-C ratio) CVD risk factors. Flynn et al.20 also studied the Step 2 diet in 20 hypercholesterolemic subjects (10 men, 10 postmenopausal women) for 4 weeks and found that compared to a high-fat and high-saturated fat “baseline” diet, the step II diet reduced TC and LDL-C ( as well as HDL-C) and increased VLDL-cholesterol and the TC: HDL-C ratio. When these same investigators combined the step II diet with an energy restriction to produce weight loss, the lipoprotein response was improved.

While Flynn et al. studied the combination of the AHA-recommended diet with energy reduction (weight loss), we could find no previously published clinical trials that examine the combined effects of the AHA Step 2-type diet with exercise on CVD-related lipid responses. Our analysis is based on results from two dietary instruments administered multiple times to characterize diet patterns in the context of and over the duration of an exercise intervention, an approach considerably superior to using a single food frequency questionnaire. We observed that, even with diet patterns that were far from the AHA “ideal”, previously sedentary, overweight subjects were able to achieve widespread beneficial improvements in their “at risk” lipid profiles when they participated in a comprehensively applied program of aerobic exercise. In contrast to our hypothesis, this was true for all three of the exercise treatment levels in STRRIDE I.

Again we underscore that our findings should not be interpreted to mean that exercise negates the importance of a good diet in lipid management. It is likely that sufficiently poor dietary choices (worse than those we observed in this population) could overwhelm some or all of the exercise benefits. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that the AHA diet offers a number of health benefits in addition to effects on plasma lipids. Nonetheless, the clinically important implication of our “negative” finding is that even when limiting themselves to one major lifestyle change (in this case, exercise), at-risk individuals can still achieve a sustained reduction of lipid-related CVD risk.

We recognize the limitations of our study, which was not designed to examine a specific dietary intervention but, rather, to track nutritional patterns during an intense exercise intervention. There was a very slight amount of weight loss in the exercise groups (range of 0.6 to 1.8 kg); however, this change was attributed to exercise because we found no relationship between weight change and caloric intake change over time (P=0.42, data not shown). Moreover, this amount of weight loss would be very unlikely to produce any physiologically important change in lipid profiles. Further, while the dietary z-score used here was based on AHA recommendations and major dietary lipid influences recognized consistently in randomized trials, we recognize that this score does not account for every dietary influence on lipids, such as amounts of sweetened drinks, fruits and nuts, or the glycemic index of carbohydrates21. Additionally, our findings are based on dietary self-report measures that are not perfect and might be susceptible to under-reporting22. Nonetheless, the use of multiple assessments and two measures of dietary patterns should minimize these effects and serves as a strength of this investigation. We also recognize that our sample size was moderate and that in a larger sample we might have detected small diet effects. However, in this sample of 204 individuals with approximately 50 participants per group, we had power to detect moderate-size, and what we believe to be clinically significant, diet pattern influences. Given the inherent difficulty of controlling calorie intake, diet composition, and exercise dose/intensity in a single study, our examination of a range of carefully monitored exercise interventions paired with detailed, longitudinal recordings of diet patterns provides valuable information about diet-exercise interactions in a population commonly prescribed to such interventions for the sake of improving lipid outcomes.

In conclusion, while it is possible to achieve beneficial changes in lipid patterns with combined dietary and physical exercise interventions, our findings challenge the assumption that a combination of the two is always required for beneficial modifications in serum lipids and lipoproteins. It seems prudent to recommend that lifestyle interventions to improve lipoprotein profiles be individualized to address the most important therapeutic goals and that interventions targeting exercise alone can achieve significant effects on a broad range of lipids, even in the presence of a suboptimal diet pattern.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the STRRIDE I participants and the rest of the STRRIDE research team at Duke University Medical Center and East Carolina University. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents. The manuscript was drafted by KMH and CWB and edited by all authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures and Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Kodama S, Tanaka S, Saito K, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise training on serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(10):999–1008. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Franklin B. Aerobic exercise and lipids and lipoproteins in patients with cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006;26(3):131–139. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200605000-00002. quiz 140–1, discussion 142–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraus WE, Torgan CE, Duscha BD, et al. Studies of a targeted risk reduction intervention through defined exercise (STRRIDE) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(10):1774–1784. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200110000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraus WE, Houmard JA, Duscha BD, et al. Effects of the amount and intensity of exercise on plasma lipoproteins. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(19):1483–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2008

- 6.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006;114(1):82–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. Epub 2006 Jun 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Summary of American Heart Association Diet and Lifestyle Recommendations revision 2006. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(10):2186–2191. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000238352.25222.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: new recommendations from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(2):151–152. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000057393.97337.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women–2011 update: a guideline from the american heart association. Circulation. 2011;123(11):1243–1262. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Horn L, McCoin M, Kris-Etherton PM, et al. The evidence for dietary prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(2):287–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, et al. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1601–1613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckel RH, Borra S, Lichtenstein AH, et al. Understanding the complexity of trans fatty acid reduction in the American diet: American Heart Association Trans Fat Conference 2006: report of the Trans Fat Conference Planning Group. Circulation. 2007;115(16):2231–2246. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.181947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown L, Rosner B, Willett WW, et al. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(1):30–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wirfalt AK, Jeffery RW. Using cluster analysis to examine dietary patterns: nutrient intakes, gender, and weight status differ across food pattern clusters. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(3):272–279. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(97)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millen BE, Quatromoni PA, Nam BH, et al. Dietary patterns, smoking, and subclinical heart disease in women: opportunities for primary prevention from the Framingham Nutrition Studies. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(2):208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fung TT, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, et al. Dietary patterns and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1857–1862. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu FB, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Prospective study of major dietary patterns and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(4):912–921. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtenstein AH, Ausman LM, Jalbert SM, et al. Efficacy of a Therapeutic Lifestyle Change/Step 2 diet in moderately hypercholesterolemic middle-aged and elderly female and male subjects. J Lipid Res. 2002;43(2):264–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flynn MM, Zmuda JM, Milosavljevic D, et al. Lipoprotein response to a National Cholesterol Education Program step II diet with and without energy restriction. Metabolism. 1999;48(7):822–826. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L. Components of a cardioprotective diet: new insights. Circulation. 2011;123(24):2870–2891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang TT, Roberts SB, Howarth NC, et al. Effect of screening out implausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. Obes Res. 2005;13(7):1205–1217. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison DB, Egan SK, Barraj LM, et al. Estimated intakes of trans fatty and other fatty acids in the US population. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(2):166–174. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00041-3. quiz 175–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bazzano LA, He J, Ogden LG, et al. Dietary fiber intake and reduced risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(16):1897–1904. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.16.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]