Abstract

Previous work has shown that older adults encode lexical and semantic information about verbal distractors and use that information to facilitate performance on subsequent tasks. In this study, we investigated whether older adults also form associations between distractors and co-occurring targets. In two experiments, participants performed a 1-back task on pictures superimposed with irrelevant words; 10 min later, participants were given a paired-associates memory task without reference to the 1-back task. The study list included preserved and re-paired (disrupted) pairs from the 1-back task. Older adults showed a memory advantage for preserved pairs and a disadvantage for disrupted pairs, whereas younger adults performed similarly across pair types. These results suggest the existence of a hyper-binding phenomenon in which older adults encode seemingly extraneous co-occurrences in the environment and transfer this knowledge to subsequent tasks. This increased knowledge of how events covary may be the reason why real-world decision-making ability is retained, or even enhanced, with age.

Keywords: inhibition, attention, associative memory, aging, binding

Many experimental tasks include distraction, either intentionally (e.g., in visual search and flanker tasks; Eriksen & Schultz, 1979; Treisman & Gelade, 1980) or unintentionally (e.g., in classic perceptual speed tasks; Lustig, Hasher, & Tonev, 2006). In either case, relative to younger adults’ performance, older adults’ performance on a concurrent target task is differentially influenced by the presence of distraction, which usually disrupts performance of the target task (Lustig et al., 2006; Rabbit, 1965) but occasionally facilitates it (May, 1999). Such findings are consistent with the idea that the bandwidth of attention (Jonides et al., 2008) is greater for older than younger adults. This phenomenon is due, at least in part, to reduced inhibitory regulation, which otherwise suppresses representations of nonrelevant information (Hasher, Zacks, & May, 1999; Wühr & Frings, 2008).

It is not surprising, then, that when words serve as distractors, older adults encode both lexical and semantic information about those items, which suggests that one result of reduced inhibitory regulation is excessive (or hyper-) encoding of nonrelevant information (Kim, Hasher, & Zacks, 2007; Rowe, Valderrama, Hasher, & Lenartowicz, 2006). An additional by-product of the failure to down-regulate nonrelevant information is that representations of distraction from a previous task are still accessible during subsequent tasks and may influence performance on them (Healey, Campbell, & Hasher, 2008). For example, one study showing transfer from previously seen distractors used as its encoding task a 1-back procedure in which participants were to respond whenever two identical pictures occurred in a row (Rowe et al., 2006); superimposed over each picture was an irrelevant letter string or word, which participants were told to ignore. Knowledge of some of the distracting words was tested 10 min later, using an implicit fragment-completion test. Although younger adults showed virtually no priming, older adults showed substantial priming from the distractors, a finding that is consistent with the view that reduced inhibitory regulation allows for the encoding of more information, and that once information is encoded, access to it is sustained even when tasks change (e.g., Hasher et al., 1999).

We note that the procedure used by Rowe et al. (2006) exposed a target and a distractor simultaneously and that older adults attended to both items, the very circumstance under which automatic binding is proposed to occur (Logan & Etherton, 1994; Moscovitch, 1994). Given that poor attentional control results in a sort of hyper-encoding, in which more irrelevant information than intended is encoded by older adults, this attentional deficit may also set the stage for hyper-binding, in which more information than intended may be bound together by older adults than by younger adults.

We investigated this possibility in two experiments, using a variant of the 1-back procedure employed by Rowe et al. (2006). After a brief delay, participants were given a paired-associates list to learn; some of the test pairs were preserved from the 1-back task, whereas other items were re-paired (disrupted pairs). We hypothesized that if older adults did not simply encode distractors but also bound them to their simultaneously presented targets, and if those bindings, like the distractors themselves, remained accessible, then older adults would show a memory advantage for preserved pairs over disrupted pairs. If, however, older adults had access only to the old distractor words, then performance on preserved and disrupted pairs would be equal. Younger adults, in contrast, were expected to perform similarly across pair types, because they were expected to be able to ignore the distractor words on the 1-back task, and therefore fail to bind them to the targets.

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we examined age differences in memory for preserved and disrupted pairs relative to new picture-word pairs that were not previously seen on the 1-back task.

Method

Participants

Participants were 24 younger adults (ages 17–29 years, M = 19.04, SD = 2.40; 3 males, 21 females) and 24 older adults (ages 60–73 years, M = 66.63, SD = 4.15; 7 males, 17 females). The younger adults were undergraduate students at the University of Toronto and received partial course credit for their participation; the older adults were recruited from the community and received monetary compensation for their participation. Data from 9 younger and 7 older participants were replaced, for a variety of reasons: Seven were aware of a connection between the critical tasks (5 young, 2 old); 6 did not understand task instructions (3 young, 3 old); 1 younger adult scored below the cutoff (< 20/40) on the vocabulary test; and 2 older adults were excluded because of experimenter error.

The younger adults had an average of 13.04 (SD = 1.49) years of education and a mean score of 29.48 (SD = 3.67) on the Shipley Vocabulary Test (Shipley, 1946). The older adults had more years of education than the younger adults did, M = 16.92, SD = 3.90, t(46) = 4.55, p < .01 (this is not uncommon in the literature; e.g., Chalfonte & Johnson, 1996), and the older adults scored higher on the vocabulary test than the younger adults did, M = 35.49, SD = 3.47, t(46) = 5.84, p < .01 (this is widely reported in the individual differences and cognitive aging literatures; Verhaeghen, 2003). All participants reported being in good health and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing.

Materials

Twenty-seven line drawings (12 critical items and 15 fillers) were selected from Snodgrass and Vanderwart (1980) and colored red. The critical pictures, which would later serve as cues on the paired-associates task, were divided into three lists of 4 pictures that were matched on familiarity, name agreement, Kucera-Francis frequency, and number of syllables. In addition, 52 two-syllable nouns (12 critical items and 40 fillers) were selected, with the critical items divided into three lists of 4 words that were matched on imagery, concreteness, and frequency. For the memory task, pictures and words from the critical lists were randomly paired to form four preserved, four disrupted, and four new pairs. Pairings were counterbalanced in such a way that each list was rotated through the three pair-type conditions. Input lists for the 1-back task (69 trials in total) consisted of the eight critical pairs for the later memory task (preserved and to-be-disrupted; shown three times each) randomly intermixed with the 15 filler pictures (shown three times each) and the 40 superimposed filler words (shown once each).

Procedure

First, participants viewed a series of pictures on which irrelevant words were superimposed. They were instructed to ignore the distracting words and to press the space bar on a computer keyboard whenever they saw the same picture twice in a row. Each picture-word pair was presented at the center of a computer screen for 1,000 ms; the interstimulus interval (ISI) was 500 ms. The presentation sequence was as follows: 5 pictures with no words superimposed, 8 pictures on which filler words were superimposed (primacy buffer), 48 trials with either filler picture-word pairs (total of 24 pairs) or critical picture-word pairs (8 pairs shown three times each, for a total of 24 pairs), and 8 pictures on which filler words were superimposed (recency buffer). Consecutive pictures occurred every 6 trials, on average (and never on critical-pair trials); critical-pair trials occurred randomly, but not consecutively, in the series.

After a 10-min interval during which participants completed nonverbal tasks, they were given the paired-associates task. No connection to the prior task was mentioned. Twelve picture-word pairs (i.e., words superimposed on the pictures) were presented in a random order for study. To avoid ceiling effects for younger adults and floor effects for older adults (e.g., Naveh-Benjamin, Brav, & Levy, 2007), we used presentation rates of 2,000 ms/pair for younger adults and 4,000 ms/pair for older adults (500-ms ISI for both).1 Immediately after studying the list, participants were shown the pictures one at a time (a different random order from study) and were asked to recall the corresponding words. Each cue was shown for 4,000 ms (500-ms ISI), and responses were given aloud. A graded awareness questionnaire followed; participants were asked if they had noticed a connection among the tasks and, if so, what the connection was. Finally, participants completed a background questionnaire and a vocabulary test.

Results and discussion

Accuracy and reaction times were analyzed for the nine pictures that were repeated on the 1-back task. Older adults were less accurate (M = .83, SD = .21) and slower to respond to repetitions (M = 631.83 ms, SD = 118.00) than younger adults (M = .98, SD = .05; M = 526.88 ms, SD = 87.06), F(1, 46) = 10.75, p < .01, prep = .98, ηp2 = .19, and F(1, 46) = 12.29, p < .01, prep = .99, ηp2 = .21, respectively. Although we did not have enough repetition trials to garner a stable measure of on-line distraction, these results suggest that older adults were more distracted by the superimposed words than younger adults were, as age differences in accuracy are rarely found on traditional 1-back tasks that do not include superimposed distraction (e.g., Mattay et al., 2006).

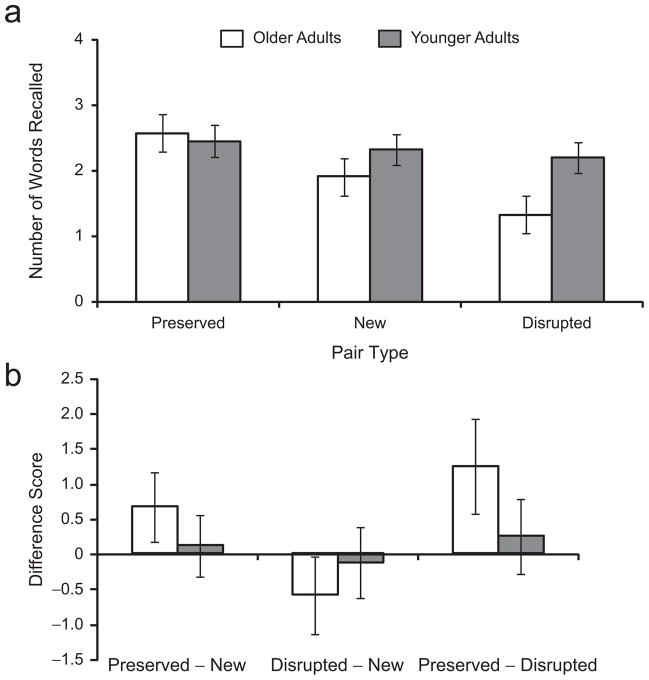

Figure 1a shows the mean number of words recalled by younger and older adults across pair type. Number of words recalled was submitted to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with age (young, old) as a between-subjects factor and pair type (preserved, new, disrupted) as a within-subjects factor. Older and younger adults did not differ in overall recall (M = 5.83, SD = 2.54, and M = 7.00, SD = 2.98, respectively), F(1, 46) = 2.09, p = .16, prep = .76, ηp2 = .04, and it is important to note that neither group performed at floor or ceiling. Participants’ recall performance was affected by pair type, F(2, 92) = 8.13, p < .01, prep = .97, ηp2 = .15, and this effect was qualified by a significant age-by-pair-type interaction, F(2, 92) = 3.62, p < .05, prep = .91, ηp2 = .07, which is illustrated in Figure 1b.

Fig. 1.

Results from Experiment 1: (a) mean number of words recalled by younger and older adults as a function of pair type and (b) mean difference in recall between pair types (preserved – new, disrupted – new, and preserved – disrupted) among younger and older adults. In (a), error bars represent 95% within-subjects confidence intervals (Masson & Loftus, 2003), which only speak to the main effect of pair type within each group. In (b), error bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the mean.

To further examine the effect of pair type, we ran separate analyses for older and younger adults. As shown in Figure 1, older adults’ recall differed across pair type, F(2, 46) = 9.55, p < .01, prep = .99, ηp2 = .29. They showed a memory advantage for preserved pairs (M = 2.58, SD = 1.25) relative to new pairs (M = 1.92, SD = 1.02), t(23) = 2.71, p < .05, prep = .95, d = 1.13, and a memory disadvantage for disrupted pairs (M = 1.33, SD = 1.27) relative to new pairs, t(23) = 2.12, p < .05, prep = .89, d = 0.88. In contrast, younger adults’ recall was not affected by pair type, F < 1; younger adults’ performance was similar for new (M = 2.33, SD = 1.31), preserved (M = 2.46, SD = 1.14), and disrupted (M = 2.21, SD = 1.14) pairs.

Although participants reported being unaware of a connection between the 1-back and paired-associates tasks, it remains a possibility that the learning effects in the older group were due to residual explicit memory for the critical 1-back pairs. To test this possibility, we ran a control experiment with two additional groups of 12 older adults (ages 62–73 years, M = 67.00, SD = 3.22; 3 males, 9 females) and 12 younger adults (ages 17–22 years, M = 19.50, SD = 1.73; 6 males, 6 females) sampled from the same pools as in Experiment 1. These participants performed the same 1-back and filler tasks as in the main experiment, and then completed two successive, explicit memory tests of association formation (in place of the paired-associates task).

The first memory test assessed cued recall of the distracting words, using the pictures from the eight critical 1-back pairs as cues. Only 1 participant from each age group was able to generate a single correct response (M = 0.08, SD = 0.29, for both groups). The cued-recall test was immediately followed by an associative matching test in which participants were given the eight critical pictures in one column and the eight corresponding words (arranged randomly) in a second column. Participants were asked to draw a line connecting each picture to its 1-back distractor. Even with this additional external support, neither older adults (M = 1.17, SD = 1.03) nor younger adults (M = 1.17, SD = 1.03) performed better than chance (1 correct match out of 8), ts < 1. Performance on these memory tests suggests that neither group had explicit memory for the 1-back pairs.

In sum, older adults’ performance on the paired-associates task was clearly influenced by their prior exposure to the picture-word pairs on the 1-back task: They showed a memory advantage for preserved pairs and a memory disadvantage for disrupted pairs. Younger adults, by contrast, were not affected by their prior experience with the pairs. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the age-by-pair-type interaction was driven by procedural differences between the groups, because study rates on the paired-associates task differed between older and younger adults. Experiment 2 was designed to solve this problem, as well as to provide a conceptual replication of the startling results of Experiment 1.

Experiment 2

In this experiment, we sought to replicate the critical hyper-binding effect of Experiment 1 using an identical procedure for younger and older adults. The major changes from Experiment 1 were on the paired-associates list that tested for binding effects. New pairs were excluded, leaving only preserved and disrupted pairs, which were presented at the same rate for older and younger participants.

As in Experiment 1, we expected older adults to inadvertently bind distracting words to target pictures on the 1-back task and thus to show a memory advantage for preserved over disrupted pairs on the paired-associates task. Younger adults, in contrast, were expected to successfully inhibit the distracting words on the 1-back task and to show no difference in memory performance across pair types.

Method

Participants

Participants were 20 younger adults (ages 18–27 years, M = 19.45, SD = 2.04; 10 males, 10 females) and 20 older adults (ages 60–75 years, M = 67.60, SD = 4.51; 8 males, 12 females) drawn from the same pools as in Experiment 1. Data from 3 older participants were replaced because of participants’ awareness of a connection between the critical tasks.

The younger adults had an average of 13.15 (SD = 1.90) years of education and a mean score of 31.64 (SD = 3.61) on the Shipley Vocabulary Test (Shipley, 1946). Once again, older adults had more years of education, M = 16.03, SD = 2.06, t(38) = 4.60, p < .01, and scored higher on the vocabulary test, M = 36.34, SD = 2.63, t(38) = 4.71, p < .01, than younger adults did. All participants reported being in good health and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing.

Materials and procedure

The picture and word materials were similar to those used in Experiment 1, except that 16 critical pictures and 16 critical words were each divided into two lists of 8 stimuli. These were randomly paired to form four sets of 8 preserved and 8 disrupted pairs for the memory task. Input lists for the 1-back task (total of 102 trials) consisted of the 16 critical pairs for the later memory task (preserved and to-be-disrupted; shown three times each) randomly intermixed with 18 filler pictures and words (shown three times each). Unlike in Experiment 1, filler words were also repeated three times each, although never with the same filler picture. We repeated filler words in an attempt to lessen participants’ awareness of a connection between the tasks by further reducing the distinction between critical and filler materials.

The procedure was the same as that used in Experiment 1, except that the presentation rate during the study phase of the paired-associates task was 4,000 ms/pair for both age groups.

Results and discussion

Accuracy and reaction times were analyzed for the 17 pictures that were repeated on the 1-back task. Older adults were again less accurate (M = .89, SD = .13) and slower to respond to repetitions (M = 599.91 ms, SD = 73.73) than younger adults were (M = .99, SD = .03; M = 543.39 ms, SD = 73.04), F(1, 38) = 9.51, p < .01, prep = .97, ηp2 = .20, and F(1, 38) = 5.93, p < .05, prep = .93, ηp2 = .14, respectively.

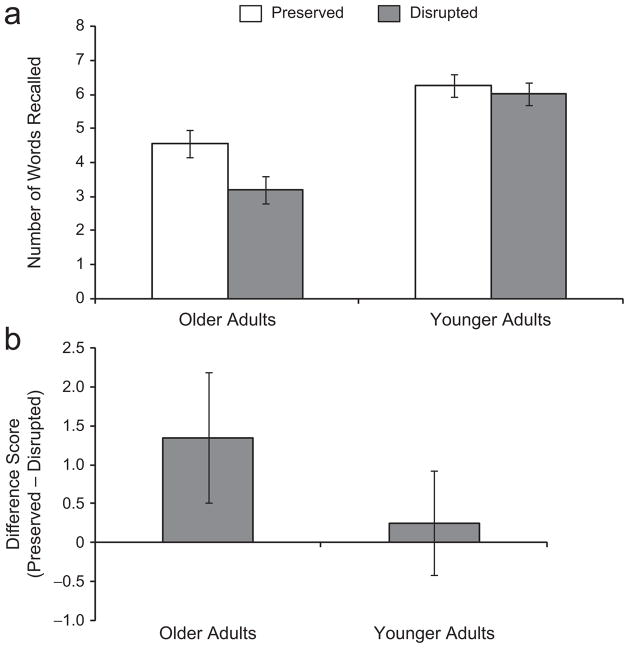

Figure 2a shows the mean number of words recalled by younger and older adults across pair types. Number of words recalled was submitted to an ANOVA with age (young, old) as a between-subjects factor and pair type (preserved, disrupted) as a within-subjects factor. Older adults (M = 7.75, SD = 4.45) recalled fewer words overall than younger adults did (M = 12.25, SD = 3.49), F(1, 38) = 12.67, p < .01, prep = .99, ηp2 = .25, a result reflecting younger adults’ typically superior paired-associates performance at this slower study rate. As in Experiment 1, recall performance was affected by pair type, F(1, 38) = 9.70, p < .01, prep = .97, ηp2 = .20, and this effect was qualified by a significant age-by-pair-type interaction, F(1, 38) = 4.58, p < .05, prep = .89, ηp2 = .11, as illustrated in Figure 2b.

Fig. 2.

Results from Experiment 2: (a) mean number of words recalled by younger and older adults as a function of pair type and (b) mean difference in recall between preserved and disrupted pairs among younger and older adults. Error bars represent 95% within-subjects confidence intervals for (a) and 95% confidence intervals of the mean for (b).

A separate analysis was then run for each age group. Once again, older adults’ memory performance differed across pair types, F(1, 19) = 11.44, p < .01, prep = .97, ηp2 = .38, as they recalled a greater number of preserved pairs (M = 4.55, SD = 2.52) than disrupted pairs (M = 3.20, SD = 2.26). In contrast, younger adults recalled a similar number of preserved (M = 6.25, SD = 2.00) and disrupted (M = 6.00, SD = 1.78) pairs, F < 1. As in Experiment 1, only the older group showed a memory advantage for preserved over disrupted pairs, which suggests that they alone possessed, and subsequently used, implicit knowledge of the associative link between the target pictures and distracting words.

General Discussion

Our results dramatically demonstrate that older adults form associations between target and distracting information and tacitly use this knowledge on a subsequent task. These findings suggest a hyper-binding phenomenon, whereby older adults actually associate too much information rather than too little, an effect tied to age-related reductions in the ability to suppress distraction.

Clearly, older adults encode distracting words and bind them to co-occurring targets, have access to these associations up to 10 min later, and tacitly use this information on a paired-associates memory task. Older adults’ knowledge of previously irrelevant associations boosted their memory for maintained pairs and, in Experiment 1, interfered with their ability to form new associations between disrupted pairs. The data from Experiment 2 are consistent in showing an advantage for preserved over disrupted pairs among older adults. Furthermore, these transfer effects seem to rely solely on implicit memory, because older adults were unable to explicitly recall or recognize the critical 1-back pairs. In contrast, younger adults’ memory performance was unaffected by pair type.

There are three possible reasons why younger adults failed to show the same effect as older adults: (a) They may not have encoded the distracting words; (b) they may have encoded the distracting words but not bound them to the target pictures; and (c) they may have formed associations between targets and distractors, but this implicit knowledge may have failed to affect explicit learning. Previous work suggests that the first option is the most likely, as younger adults who were tested with a similar picture-word, 1-back paradigm showed little implicit memory for the distracting words themselves on a later word-fragment completion task (Rowe et al., 2006). Younger adults are better at tuning out, or suppressing, irrelevant distraction than older adults are (e.g., May, 1999), and, as a result, they are less likely to form potentially superfluous associations between target and distracting information.

The findings for older adults are predicted by models of cognition that assume that for targets to be selected in the face of distraction, representations of familiar irrelevant items must be suppressed (Healey, Campbell, Hasher, & Ossher, 2009). The notion is that the ability to suppress is particularly compromised (Hasher et al., 1999) in older adults, in some young adult university students as a result of individual differences (Gazzaley, Cooney, Rissman, & D’Esposito, 2005; Healey, Zacks, Hasher, & Helder, 2009), and in other individuals with compromised attention abilities (e.g., Nigg, Carr, Martel, & Henderson, 2007). Hasher and her colleagues have argued that initial selection is compromised by inhibitory dysfunction, as is deselection whenever activated representations become irrelevant (as, e.g., in the face of new tasks). The present findings fit well within this theoretical framework.

These results suggest an additional consequence of poor inhibitory control, namely hyper-binding, or the obligatory formation of overly broad associations between events occurring in close temporal and spatial contiguity. If older adults have access to more irrelevant information (e.g., May, 1999), and if co-occurring items are automatically bound together (Logan & Etherton, 1994; Moscovitch, 1994), then older adults will bind too much information together rather than too little. Although these broad associations may sometimes prove useful, as with the preserved pairs in the current paradigm, at other times they will lead to disruption, as with the recombined pairs (relative to new pairs) in Experiment 1. The latter finding ties back to explicit learning and memory literature suggesting that older adults are deficient at forming new associations (e.g., Naveh-Benjamin, 2000; Chalfonte & Johnson, 1996). Our results make the unique suggestion that age differences in associative memory may be caused, in part, by interference from excessive binding, an effect similar to fan and cue overload effects seen in item memory (Anderson, 1974; Watkins & Watkins, 1975). The present results suggest that whatever binding resources older adults do have will often be misguided toward extraneous information. Traditional tests of associative memory are rife with the opportunity for formation of inappropriate associations (e.g., between a current target item and a previous or subsequent one), and older adults’ susceptibility to these associations may exaggerate the extent of their associative deficit.

Although the proposed hyper-binding effect may lead to greater interference on traditional tests of associative memory, it may also mean that older adults and other individuals with reduced attentional regulation will have greater knowledge of seemingly extraneous co-occurrences in the environment. Knowledge of how events covary in everyday life is thought to underlie people’s ability to determine cause and effect, playing a critical role in the ability to behave adaptively (for reviews, see Crocker, 1981; Sedlmeier, 2005). Further, even if this associative knowledge remains implicit, it can affect explicit learning processes. These observations suggest a means by which older adults’ tacit knowledge may surreptitiously serve everyday reasoning and problem solving, processes widely thought to rely on implicit knowledge and intuitive reasoning (Gigerenzer, 2008; Hogarth, 2005; McKenzie, 1994). The present findings lead to the exciting prediction that older adults may sometimes outperform younger adults in real-world decision-making scenarios that call upon knowledge of previously irrelevant co-occurrences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Howard and Lindsay McAlear for their assistance with data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP89769) and by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Grant R37 AGO4306).

Footnotes

Six younger adults who were initially given the 4,000-ms/pair study rate all performed at ceiling.

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interests with respect to their authorship and/or the publication of this article.

References

- Anderson JR. Retrieval of propositional information from long-term memory. Cognitive Psychology. 1974;6:451–474. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfonte BL, Johnson MK. Feature memory and binding in young and older adults. Memory & Cognition. 1996;24:403–416. doi: 10.3758/bf03200930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J. Judgment of covariation by social perceivers. Psychological Bulletin. 1981;90:272–292. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen CW, Schultz DW. Information processing in visual search: A continuous flow conception and experimental results. Perception & Psychophysics. 1979;25:249–263. doi: 10.3758/bf03198804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Cooney JW, Rissman J, D’Esposito M. Top-down suppression deficit underlies working memory impairment in normal aging. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1298–1300. doi: 10.1038/nn1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer G. Why heuristics work. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:20–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT, May CP. Inhibitory control, circadian arousal, and age. In: Gopher D, Koriat A, editors. Attention and performance XVII. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 653–675. [Google Scholar]

- Healey MK, Campbell KL, Hasher L. Cognitive aging and increased distractibility: Costs and potential benefits. In: Sossin WS, Lacaille JC, Castellucci VF, Belleville S, editors. Progress in brain research: Vol. 169. Essence of memory. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey MK, Campbell KL, Hasher L, Ossher L. Direct evidence for the role of inhibition in resolving interference. 2009. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey MK, Zacks RT, Hasher L, Helder E. Inhibition and the relationship between working memory and fluid intelligence. University of Toronto; Toronto, Ontario, Canada: 2009. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth RM. Deciding analytically or trusting your intuition? The advantages and disadvantages of analytic and intuitive thought. In: Betsch T, Haberstroh S, editors. The routines of decision making. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Lewis RL, Nee DE, Lustig CA, Berman MG, Moore KS. The mind and brain of short-term memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:193–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Hasher L, Zacks RT. Aging and a benefit of distractibility. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2007;14:301–305. doi: 10.3758/bf03194068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Etherton JL. What is learned during automatization? The role of attention in constructing an instance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1994;20:1022–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, Hasher L, Tonev ST. Distraction as a determinant of processing speed. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2006;13:619–625. doi: 10.3758/bf03193972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson MEJ, Loftus GR. Using confidence intervals for graphically based data interpretation. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2003;57:203–220. doi: 10.1037/h0087426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattay VS, Fera F, Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Berman KF, Das S, et al. Neurophysiological correlates of age-related changes in working memory capacity. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;392:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May CP. Synchrony effects in cognition: The costs and a benefit. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1999;6:142–147. doi: 10.3758/bf03210822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie CRM. The accuracy of intuitive judgment strategies: Covariation assessment and Bayesian inference. Cognitive Psychology. 1994;26:209–239. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch M. Memory and working with memory: Evaluation of a component process model and comparisons with other models. In: Schacter DL, Tulving E, editors. Memory systems 1994. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994. pp. 269–311. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh-Benjamin M. Adult age differences in memory performance: Tests of an associative deficit hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2000;26:1170–1187. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.5.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveh-Benjamin M, Brav TK, Levy O. The associative memory deficit in older adults: The role of strategy utilization. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:202–208. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Carr LA, Martel MM, Henderson JM. Concepts of inhibition and developmental psychopathology. In: MacCleod C, Gorfein D, editors. Inhibition in cognition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2007. pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbit PMA. An age deficit in the ability to ignore irrelevant information. Journal of Gerontology. 1965;20:233–238. doi: 10.1093/geronj/20.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe G, Valderrama S, Hasher L, Lenartowicz A. Attentional disregulation: A benefit for implicit memory. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:826–830. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlmeier P. From associations to intuitive judgment and decision making: Implicitly learning from experience. In: Betsch T, Haberstroh S, editors. The routines of decision making. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley WC. Institute of Living Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Vanderwart M. Norms for picture stimuli. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 1980;6:205–210. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.6.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman AM, Gelade G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology. 1980;12:97–136. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P. Aging and vocabulary scores: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:332–339. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins OC, Watkins MJ. Buildup of proactive inhibition as a cue-overload effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 1975;1:442–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wühr P, Frings C. A case for inhibition: Visual attention suppresses the processing of irrelevant objects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2008;137:116–130. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.137.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]