Abstract

Introduction

Physical activity programs have health benefits for cancer survivors, but little is known about factors that influence cancer survivors' actual choices between different physical activity programs. To address this knowledge gap, we examined factors associated with selecting between two group physical activity programs.

Methods

The present study is nested in a non-randomized trial. After attending an orientation to learn about the programs offered, cancer survivors (n=133) selected between a dragon boat paddling team and group walking program. We measured the association between physical activity program chosen and demographic, clinical, physical and psychosocial characteristics.

Results

Roughly equal proportions chose to participate in dragon boat paddling or walking (55% versus 45%). Of the many variables studied, few were associated with program selection. Compared to those who chose the walking program, those who chose the dragon boat paddling team were more likely to be Caucasians (p = .015) and younger (p= .027), and marginally signifantly more like to have cancers other than breast cancer (p=.056) and have greater lower body strength (.062).

Discussions/Conclusions

Among a cohort of cancer survivors who were interested in physical activity programs who chose between two markedly different group physical activity programs, the two programs attracted groups of approximately the same size and with remarkably similar characteristics overall. The two most notable associations were that Caucasians and younger adults were significantly more likely to choose the dragon boat paddling program.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

To meet the needs of cancer survivors, a menu of physical activity program options may be optimal.

Keywords: Cancer, Oncology, Physical Activity, Quality of Life, Physical Fitness, Selection

INTRODUCTION

Physical activity improves both emotional and physical functioning of cancer patients. Interventions to increase exercise during cancer treatment are associated with improvements in patients' functional capacity, strength, and sleep patterns and lessened cancer and treatment-induced symptoms such as nausea, fatigue, and pain [1]. By reducing negative mood [2, 3] and fatigue [4–6], and increasing functional capacity and physical fitness [7–9], exercise interventions may enhance cancer survivors' quality of life [10] and survival [11, 12].

Seventy percent or more of cancer survivors express interest in participating in physical activity programs [13–20]. Evidence is needed about factors that influence choices between different types of physical activity programs so that physical activity interventions are offered that can satisfy this demand. To date, most research in this area has assessed cancer survivors' hypothetical preferences for physical activity programs [13–20]. Most survivors prefer a program of moderate intensity to start during or shortly after their primary cancer treatment [13, 14, 16, 17]. Most also prefer to engage in physical activity independently or with those they know, but 5% to 27% would prefer to exercise with other cancer survivors [13–17, 19, 21].

To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined cancer survivors' actual choices of program participation and factors associated with those choices. The purpose of the present report was to address this evidence gap, taking advantage of a parent study, a non-randomized intervention trial designed to compare two types of physical activity programs, a team-oriented dragon boating program (intervention group) and a group-based walking program (comparison group). Dragon boating is a competitive team sport in which 22 paddlers sit two abreast in colorful 48-foot vessels while paddling to the beat of a drummer, the heartbeat of the dragon. A non-randomized procedure was used in the present study due to concerns regarding randomization to a water sport until more was learned about potential barriers associated with participating in a water-based activity. This study milieu offered an ideal opportunity to study factors associated with choosing between participation in two distinct physical activity programs.

The rationale for the physical activity programs offered was based on both conceptual and practical grounds. First, dragon boating is a team-based sport that has become increasingly popular among cancer survivors since 1996, when there was one cancer survivor dragon boat team in British Columbia, to the present day, when hundreds of cancer survivor dragon boat teams race throughout North America. Second, physical activity in a team environment has unique elements that may benefit cancer survivors. Third, competitive team sports have rarely been included in studies of physical activity in cancer survivors. For example, using search terms “neoplasms” or “cancer” AND “team sports” or “team” or “group,” we searched seven bibliographic databases. Only five articles related to competitive/team sports among adult cancer survivors were ascertained; all were related to dragon boating [22–26].

The rationale for offering a walking program as a comparison intervention was that it was a group-based physical activity program, but with the key difference that it is not a team-based competitive sport. Walking has consistently been observed to be the favorite exercise choice for cancer survivors [13–18, 20]. In contrast to the dragon boat paddling team, walking requires no special expertise or equipment and can be done almost anywhere.

By virtue of being a non-randomized trial, the parent study provided an opportunity to generate needed evidence concerning cancer survivors' choice between two different physical activity programs. The focus of the present report is not on the outcomes of the parent study, but studying factors associated with cancer survivors' choice between the dragon boat paddling team and group-based walking program.

METHODS

Design and Participants

Study Design

The parent study was a non-randomized intervention trial to compare the physical and quality-of-life effects of participation in an 8-week team-oriented dragon boat paddling program versus a group oriented walking program. The paddling and walking programs were designed to be as similar as possible (See Figure 1). Both programs met for one hour twice weekly during an 8 week period. The paddling and walking program sessions were also structured as similarly as possible by being one hour long, having period for warm-up, practicing specific skills, and cool-down, and were led by experienced coaches or trainers. Paddling sessions initially focused on technique and timing. To maintain group contact while allowing for individually-paced walking cadence, the walking groups took place at a track or park with a looped walking path. The similarly designed programs allowed inferences to be based on selection of the actual physical activity program rather than logistical details of the programs. We implemented the physical activity interventions in three separate rounds: fall, 2007; spring, 2008; and fall, 2009. During each intervention round, the same protocol was followed. After being presented with information about the dragon boating and walking program, cancer survivors interested and physically able to participate selected one of the two programs.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Paddling and Walking Physical Activity Groups

Study Population

Participants were male and female adult cancer survivors who resided in the Charleston, South Carolina metropolitan area. Inclusion criteria were (a) age 18 years or older, (b) diagnosis of cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) regardless of time since diagnosis, and (c) sufficient functional status to engage in an exercise program. Exclusion criteria were (a) inability to obtain physician clearance to participate, (b) inability to commit to at least 13 out of 16 physical activity sessions, (c) inability to read/write English, and (d) previous participation in dragon boating. It was not possible to preclude previous experience with walking, but participants had no previous involvement with the walking program designed for the current study. All study procedures, including written informed consent, were reviewed and approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board. Participants received an honorarium for their participation.

Recruitment

A multi-pronged survivor recruitment strategy was used for each of the three separate rounds of recruitment. Advertisements were targeted to a diverse community population including cancer support organizations, academic and community cancer centers, and earned media. Study advertisements encouraged interested cancer survivors to contact the study coordinator, who described the study and screened potential participants for eligibility. Interested and eligible participants were scheduled to attend an in-person study orientation session. At the orientation meeting, the principal investigator (CLC) provided detailed study information, eligibility criteria, and requirements for participation in both the paddling and walking programs. Participants were provided an opportunity to ask questions which were then addressed by the investigator in an open format. As the orientation meeting concluded, attendees who chose to participate were asked to select one of the two exercise programs by marking a corresponding box provided on program materials. Participants were required to provide physician clearance before beginning their participation.

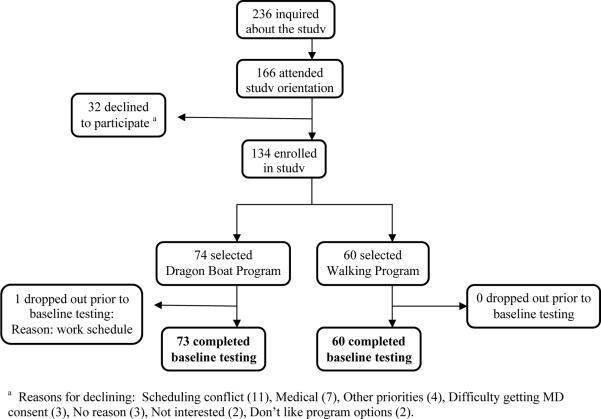

An overview of recruitment is presented in Figure 2. A total of 236 individuals inquired about the study, and 166 attended a study orientation meeting. Of these, 134 (81%) chose to participate and selected an exercise program (paddling or walking). Among the thirty-two attendees who opted not to participate in the program, scheduling barriers were provided as the primary reason for non-participation, with only two citing a dislike of program options as a reason for not joining the study. Of the 134 who chose to participate, one person dropped out prior to baseline testing. The remaining 133 (73 paddlers, 60 walkers) form the study population for the present report.

Figure 2.

Study Recruitment Summary

Measurement

Following the recruitment orientation meeting, informed consent was obtained from participating survivors at the first of two baseline evaluation sessions. The first evaluation assessed baseline measurements of aerobic capacity. Participants were also asked to complete a take-home, self-report questionnaire assessing socio-demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables and to return their questionnaire at their second baseline (strength testing) session scheduled two days later. Aerobic capacity and strength testing sessions were divided by two days to ensure that fatigue from the aerobic evaluation did not impede accurate strength testing.

Demographic Factors

Demographic information included age, race, gender, marital status, level of education, level of income, and work status.

Clinical Factors

Patient self-reported health history included type and stage of cancer at diagnosis, date of diagnosis, recurrence status, current treatment (yes/no), type of treatment if currently in treatment (surgery, radiation, surgery), and tobacco use during the past month (use of cigarettes, cigars, pipes, smokeless tobacco) (yes/no).

Previous Team and Group Participation

Previous group participation in the past 12 months (yes/no), previous team participation in the past 12 months (yes/no) and previous team participation in one's lifetime (yes/no) were assessed.

Physical Factors

Supervised by an exercise physiologist, each participant completed a baseline aerobic capacity evaluation. The Modified Bruce Walk Test, a graded walking exercise comparing pre-post performance, was used to assess aerobic fitness [27]. Strength was evaluated on Cybex isotonic weight machines, using a seated row procedure and a leg press machine for upper and lower body strength, respectively. For both, the maximal weight that a participant could resist one time was estimated by the amount of weight that they could resist between 1–10 times. As generally recommended for a population who may be aging, sedentary or ill, aerobic and strength tests were conducted using sub-maximal testing [28].

Psychosocial Factors

Outcome measures for the trial were conceptualized according to both global and cancer-specific quality-of-life, as well as measures of fatigue, benefit finding, depression, and spirituality as described below.

The MOS 36-Item Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-36) consists of 36 questions divided into 8 sub-scales: 1) physical functioning, 2) role physical, 3) bodily pain, 4) general health, 5) vitality, 6) social functioning, 7) role emotional, and 8) mental health. Two component summary measures, mental health and physical health, were calculated from the sub-scales [29, 30]. The Cronbach's alpha obtained in the current population were .89 for physical functioning, .88 for role functioning, .88 for bodily functioning, .77 for general health, .89 for vitality, .64 for social functioning, .84 for role functioning, and .74 for mental health.

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), a cancer-specific quality-of-life instrument, contains 27 likert-scale items that can be combined to calculate an overall composite score. Responses range from 0 to 4 (“not at all,” “very much,” “a little bit”, “somewhat”, “quite a bit” and “very much”) and items comprise 4 subscales: 1) physical well-being, 2) social/family well-being, 3) emotional well-being and 4) functional well-being [31]. The Cronbach's alpha in the current study population was .83 for physical well-being, .87 for social/family well-being, .75 for emotional well-being, and .85 for functional well-being.

Fatigue was assessed using the Piper Fatigue Scale. Twenty-two questions rated on a scale from 1 to 10 with higher scores representing more fatigue measured 4 dimensions of fatigue: 1) behavioral/severity, 2) affective meaning, 3) sensory and 4) cognitive/mood; an overall fatigue score was calculated [32]. The Cronbach's alphas were .96 for behavioral/severity, .97 for affective meaning, .95 for sensory, and .92 for cognitive/mood.

The Benefit Finding Scale is composed of 17 items measuring perceived benefits arising from the cancer experience [33, 34]. Each question is scored on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher values representing higher benefit (Cronbach's alpha = .96).

Depression was measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CESD) consisting of 20 items, each measured on a scale from 0 to 3 [35]. Positive items were reversed so that a higher score represented greater level of distress (Cronbach's alpha = .91).

Spirituality and Religion were measured using the Spirituality Scale, along with measures of religious affiliation, terms of spirituality or religious identity and level of religiousness as described below. The Spirituality Scale is comprised of 23 questions on a scale from 1 to 6 with higher values indicating higher spirituality [36]. Three subscales and a composite score were calculated. (Cronbach's alpha = .87 for self-discovery, .83 for relationship and .93 for eco awareness). Religious affiliation (none, Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, other), terms of spiritual or religious identify (neither, spiritual, religious, both), and level of religiousness (low/very low, medium, very high/high) were assessed.

Reasons for Program Selection

An open-ended format was used to assess respondents' reasons for choosing one of the physical activity programs and not choosing the alternate physical activity program offered. Participants could provide more than one answer.

Statistical Analysis

For purposes of this report, the study outcome was the physical activity program selected, dragon boat paddling team or group walking program. The independent variables included the demographic, clinical, physical (aerobic and strength) and quality of life measurements. For each intervention group we present descriptive statistics for the independent variables, such as means and standard deviations for the continuous variables and percentages for the categorical variables. We used generalized linear mixed models allowing for intervention-specific round to identify relationships between variables of interest (demographic and clinical factors, previous group and team participation, physical and psychological factors) and program selection. These models were implemented in SAS using the glimmix procedure with a binary distribution for the outcome and a logit link function for the relationship with the predictor variables. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participants' characteristics according to program selected are presented in Table I. Overall, the study participants were approximately 80% female and 80% Caucasian. The two programs attracted nearly equal proportions of men and women, and other demographic variables that did not differ between the two physical activity program participants were income, education, marital and work status. Differences were present for age and race. On average, those who selected the paddling program were younger than those who selected the walking program (54.2 versus 58.2 years, respectively; p= .027). Caucasians were more likely than African Americans to select the dragon boat paddling team (p = .015). Overall, 47% of the total sample reported having participated in a group within the previous year. Previous team and group participation was not associated with the physical activity program selected.

Table I.

Characteristics of Program Participants by Physical Activity Program Selected

| Characteristics | Paddling % (n=73) | Walking % (n=60) | Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Demographic Factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age Mean(SD) | 54.2 (9.7) | 58.2 (10.3) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.995) | 0.027 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| % White | 87.7 | 70.0 | Ref. | 0.015 |

| % Black | 12.3 | 30.0 | 0.33 (0.13,0.80) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| % Male | 21.9 | 18.3 | Ref. | 0.62 |

| % Female | 78.1 | 81.7 | 0.80 (0.34, 1.91) | |

|

| ||||

| Marital Status | ||||

| % Single | 9.6 | 16.7 | Ref. | 0.48 |

| % Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 21.9 | 20.0 | 1.98 (0.57, 6.83) | |

| % Married/Have Partner | 68.5 | 63.3 | 1.88 (0.65, 5.45) | |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| % Less than College | 34.7 | 36.7 | Ref. | 0.42 |

| % College Graduate | 40.3 | 30.0 | 1.40 (0.61, 3.21) | |

| % Some Graduate + | 25.0 | 33.3 | 0.79 (0.33, 1.87) | |

|

| ||||

| Income | ||||

| % $0–$44,999 | 37.3 | 27.3 | Ref. | 0.48 |

| % $45,000–89,999 | 38.8 | 47.3 | 0.60 (0.26, 1.40) | |

| % $90,000 or more | 23.9 | 25.5 | 0.69 (0.26, 1.81) | |

|

| ||||

| Work Status | ||||

| % Not Employed | 34.3 | 48.3 | Ref. | 0.10 |

| % Employed | 65.8 | 51.7 | 1.80 (0.88, 3.65) | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical Factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Years since Diagnosis Mean (SD) | 5.0 (5.7) | 6.6 (8.3) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 0.19 |

|

| ||||

| Type of Cancer | ||||

| % Breast | 49.3 | 66.1 | 050 (0.24, 1.02) | 0.056 |

| % Other | 50.7 | 33.9 | Ref. | |

|

| ||||

| Stage at Diagnosis | ||||

| % Stage I/II | 56.2 | 68.3 | Ref. | 0.28 |

| % Stage III/IV | 26.0 | 15.0 | 2.10 (0.84, 5.23) | |

| % Unknown | 17.8 | 16.7 | 1.08 (0.41, 2.85) | |

|

| ||||

| Currently in Treatment | ||||

| % No | 74.0 | 78.3 | Ref. | 0.59 |

| % Yes | 26.0 | 21.7 | 1.25 (0.55, 2.83) | |

|

| ||||

| Recurrence History | ||||

| % No | 82.2 | 91.7 | Ref. | 0.13 |

| % Yes | 17.8 | 8.3 | 2.37 (0.78, 7.15) | |

|

| ||||

| Tobacco Use | ||||

| % No | 93.2 | 96.6 | Ref. | 0.39 |

| % Yes | 6.9 | 3.4 | 2.09 (0.38, 11.37) | |

|

| ||||

| Previous Team and Group Participation | ||||

|

| ||||

| Group Participation-Past 12 Months | ||||

| % No | 56.2 | 48.3 | Ref. | 0.39 |

| % Yes | 43.8 | 51.7 | 0.74 (0.37, 1.48) | |

|

| ||||

| Team Participation-Past 12 Months | ||||

| % No | 91.8 | 98.3 | Ref. | 0.12 |

| % Yes | 8.2 | 1.7 | 5.64 (0.64, 49.82) | |

|

| ||||

| Team Participation-Ever | ||||

| % No | 43.8 | 55.0 | Ref. | 0.21 |

| % Yes | 56.2 | 45.0 | 1.56 (0.78, 3.12) | |

Odds ratio for being a paddler

P-values were computed using univariate random effects logistic regression models allowing for round specific intercept;

a P-value <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

In our study sample, participants had breast (57%), prostate (8%), female reproductive organ (7%), hematological (6%), colorectal (5%), head and neck (5%), and other cancer types (14%). Breast cancer survivors were marginally significantly less likely than survivors of other malignancies to select the dragon boat paddling program (p = .056). There was no significant difference in program selection by years since diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, or treatment status. Choice of physical activity program was not significantly associated with aerobic capacity, upper body strength, BMI, or self-rated fitness level; but those with greater lower body strength were marginally significantly more likely to choose the dragon boat paddling program (p=.062) (Table II).

Table II.

Physical Status of Program Participants by Physical Activity Program Selected

| Physical Health Measurement | Paddlinga (n=73) | Walking a (n=60) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) b | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Aerobic Capacity (in minutes) | 10.6 (2.8) | 10.0 (3.3) | 1.072 (0.948, 1.213) | 0.26 |

|

| ||||

| Upper Body Strength (in lbs.) | 90.8 (30.4) | 84.7 (36.5) | 1.006 (0.995, 1.017) | 0.31 |

|

| ||||

| Lower Body Strength (in lbs.) | 295.2 (108.2) | 256.3 (122.7) | 1.003 (1.000, 1.006) | 0.062 |

|

| ||||

| Fitness Level (Self-assessed) | ||||

| % Not very fit | 26.0 | 35.0 | Ref. | 0.33 |

| % Somewhat fit | 72.6 | 61.7 | 1.65 (0.77, 3.54) | |

| % Extremely fit | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.54 (0.04, 6.62) | |

|

| ||||

| Body Mass Index | ||||

| % Underweight | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.35 (0.03, 4.34) | 0.71 |

| % Normal | 31.5 | 26.7 | Ref. | |

| % Overweight | 34.3 | 30.0 | 0.97 (0.40, 2.36) | |

| % Obese | 32.9 | 40.0 | 0.70 (0.30, 1.66) | |

Means and standard deviations presented unless otherwise specified.

Odds ratio for being a paddler

P-values were computed using univariate random effects logistic regression models allowing for round specific intercept;

a P-value <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

SF-36 standardized and normed scores for our sample reflected average levels typically found in the general population (Table III). Program choice was not significantly associated with either global (SF-36) or cancer-specific (FACT-G) quality of life subscales or component scores. In addition to overall quality-of-life measures, physical activity program selection was also similar with respect to fatigue, benefit finding, depression and spirituality.

Table III.

Psychosocial Factors of Program Participants by Physical Activity Program Selected

| Psychosocial Measurement | Paddling a (n=73) | Walking a (n=60) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) b | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| SF-36 Quality of Life | ||||

|

| ||||

| Physical Functioning | 83.4 (16.7) | 82.2 (19.7) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.63 |

|

| ||||

| Role Physical | 72.3 (38.1) | 76.7 (36.2) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.51 |

|

| ||||

| Bodily Pain | 70.2 (22.3) | 71.1 (23.3) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.81 |

|

| ||||

| General Health | 68.4 (20.4) | 67.8 (19.5) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.83 |

|

| ||||

| Vitality | 57.2 (21.5) | 58.4 (20.3) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.76 |

|

| ||||

| Social Functioning | 81.9 (22.3) | 86.6 (18.0) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.24 |

|

| ||||

| Role Emotional | 81.7 (32.9) | 83.0 (33.4) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.84 |

|

| ||||

| Mental Health | 78.5 (13.9) | 78.4 (13.5) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 0.94 |

|

| ||||

| FACT-G Quality of Life | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall FACT-G | 85.9 (15.2) | 88.2 (13.8) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.36 |

|

| ||||

| Physical | 23.1 (4.5) | 23.1 (4.6) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 0.95 |

|

| ||||

| Social | 21.6 (5.4) | 22.3 (5.5) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04) | 0.50 |

|

| ||||

| Emotional | 20.2 (3.6) | 20.6 (3.0) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.07) | 0.46 |

|

| ||||

| Functional | 21.0 (5.1) | 22.3 (4.9) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.02) | 0.14 |

|

| ||||

| Fatigue | ||||

|

| ||||

| % Not Fatigued | 40.3 | 51.7 | 0.64 (0.32, 1.30) | 0.21 |

|

| ||||

| Fatigue Behavioral | 3.1 (2.3) | 2.6 (2.2) | 1.10 (0.94, 1.30) | 0.23 |

|

| ||||

| Fatigue Affective Meaning | 3.4 (2.5) | 3.2 (2.7) | 1.02 (0.89, 1.17) | 0.77 |

|

| ||||

| Fatigue Sensory | 4.4 (2.1) | 4.1 (2.3) | 1.06 (0.90, 1.25) | 0.45 |

|

| ||||

| Fatigue Cognitive | 3.8 (1.9) | 3.4 (1.7) | 1.14 (0.94, 1.39) | 0.19 |

|

| ||||

| Benefit Finding | ||||

|

| ||||

| Benefit Finding | 3.58 (0.9) | 3.85 (0.9) | 0.74 (0.51, 1.08) | 0.11 |

|

| ||||

| Depression | ||||

|

| ||||

| Depression in Past Week | 10.4 (9.3) | 10.1 (8.5) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.94 |

|

| ||||

| Spirituality and Religion | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall Spirituality | 108.3 (19.2) | 112.1 (17.9) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.53 |

|

| ||||

| Self Discovery | 19.4 (3.8) | 20.0 (3.6) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 0.61 |

|

| ||||

| Relationships | 30.9 (3.7) | 31.9 (3.2) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.05) | 0.40 |

|

| ||||

| Eco-Awareness | 58.0 (13.4) | 60.7 (13.9) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.44 |

|

| ||||

| Religious Affiliation | ||||

| % None | 11.1% | 10.2% | Ref. | 0.96 |

| % Catholic | 18.1% | 15.3% | 1.16 (0.29, 4.59) | |

| % Protestant | 44.4% | 50.9% | 0.82 (0.25, 2.66) | |

| % Jewish | 4.2% | 3.4% | 1.16 (0.14, 9.56) | |

| % Other | 22.2% | 20.3% | 1.02 (0.28, 3.80) | |

|

| ||||

| Terms of Spiritual or Religious Identify | ||||

| % Neither | 11.0% | 16.7% | Ref. | 0.019 |

| % Spiritual | 57.5% | 30.0% | 2.95 (0.99, 8.80) | |

| % Religious | 4.1% | 11.7% | 0.55 (0.10, 2.88) | |

| % Both | 27.4% | 41.7% | 1.02 (0.33, 3.10) | |

|

| ||||

| Level of Religiousness | ||||

| % Low/Very Low | 19.2% | 16.7% | Ref. | 0.75 |

| % Medium | 35.6% | 31.7% | 0.97 (0.35, 2.68) | |

| % Very High/High | 45.2% | 51.7% | 0.75 (0.29, 1.96) | |

Means and standard deviations presented unless otherwise specified.

Odds ratio for being a paddler

P-values were computed using univariate random effects logistic regression models allowing for round specific intercept;

a P-value <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Participants' reasons for selecting a particular physical activity program are summarized in Table IV. The most commonly reported reasons for selecting the dragon boat paddling program included 1) want to learn a new skill; 2) paddling is fun and exciting; 3) enjoy being outside on the water and 4) enjoy paddling/boating activities. The most commonly reported reasons for selecting the walking program were 1) enjoyment of walking; 2) need an exercise program, 3) appreciate the health benefits, and 4) confident that I can walk. Dragon boat paddlers' most commonly reported reasons for not selecting the walking program included 1) already walk; 2) don't need to join group to walk; 3) want to try something new; 4) physical limitations prevent walking, and 5) walking is boring. Walkers' most common reasons for not selecting the paddling program included 1) discomfort around water; 2) physical limitations prevent paddling; 3) scheduling conflicts and 4) think paddling will be too strenuous.

Table IV.

Percentage of Study Participants Citing Reasons for their Program of Choice

| Dragon Boat Participants (n=73) % | Walking Participants (n=60) % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Most Common Reasons for Choosing Program a | |||

|

| |||

| Learn a new skill/activity | 27 | Enjoy walking | 25 |

| Dragon Boating is fun and exciting | 23 | Need an exercise routine | 15 |

| Dragon Boating is outside on the water | 22 | Health benefits/fitness | 12 |

| Like paddling/boating sports | 16 | Able to walk | 10 |

| Need an exercise routine | 12 | Scheduling | 8 |

| Meet other survivors/social interaction | 12 | Injury/chronic conditions prohibit paddling | 3 |

| Increase upper body/core strength | 10 | Wanted to lose weight | 3 |

| Dragon Boating is a team sport | 10 | Walking easier than Dragon Boating | 3 |

| Wanted to Dragon Boat | 8 | Can maintain walking after program | 3 |

| Health benefits/fitness | 8 | Regain strength after cancer | 3 |

| Already walk | 7 | ||

| Dragon Boating seems challenging | 5 | ||

| Regain strength after cancer | 4 | ||

| Scheduling | 3 | ||

| Wanted to overcome fear of water | 3 | ||

| Wanted to lose weight | 3 | ||

|

| |||

| B. Most Common Reasons for Not Choosing Alternate Program a | |||

|

| |||

| Already walk | 27 | Not comfortable around water | 20 |

| Don't need to join group to walk | 21 | Injury/chronic conditions prohibit paddling | 18 |

| Wanted to try something new | 15 | Scheduling | 12 |

| Injury/chronic conditions prohibit walking | 12 | Not strong enough to paddle | 10 |

| Walking is boring | 12 | Unable to swim | 8 |

| Scheduling | 8 | Don't like to paddle | 5 |

| Paddling more fun than walking | 7 | Too hot/too cold to Dragon Boat | 3 |

| Wanted a challenge | 3 | Dragon Boating is too group-oriented | 3 |

Consented participants allowed to select multiple reasons why they chose/did not choose each program only responses noted 2+ times included in table.

Of the total of 134 men and women who chose to join the study and made a choice between the two programs, 133 (99.3%) attended the subsequent baseline testing and 128 (96.2%) actually attended at least one physical activity program session (1 paddler and 4 walkers did not participate in any sessions). Of the 133 individuals who enrolled in the physical activity interventions the combined average attendance was 11.9 of 16 sessions (74%), and on average paddlers had significantly better attendance than walkers (p-value 0.0059).

DISCUSSION

Among cancer survivors who were interested in participating in a group physical activity program and were given a choice between two different programs, we observed roughly equal proportions chose each program. Furthermore, those who selected a team-oriented paddling sport tended to be similar to those who chose a group-based walking program across measures of socio-demographic status, physical fitness, and quality of life. Of the 46 different comparisons in our analyses, the two statistically significant differences were for the demographic characteristics of race and age: those who selected the dragon boat paddling program were more likely to be younger and Caucasian. Overall, these results indicate that few factors were strong determinants of program choice, and the demographic characteristics of the survivor population may the most important factors to consider when evaluating program options.

The predilection of older survivors for the walking program mirrors the observation in the general population that walking becomes more of a preferred activity with age . In the present study, reasons for selecting the walking program tended to reflect a sense of comfort and enjoyment with walking and confidence in ability to perform the activity. Conversely, the affinity of younger cancer survivors for the paddling program may reflect a desire on the part of younger participants to develop new skills and experience novel activities, as reasons for selecting it often included words such as “exciting” and “novel.”

Breast cancer survivors currently represent the preponderance of cancer survivors' involvement in dragon boating [39], so the finding that breast cancer survivors were marginally more likely to select the walking program than the paddling program was surprising and attests to the lack of research about what cancer survivors will select when presented with a choice. Our findings raise the possibility that survivors of other cancer types may have a strong interest in taking part in dragon boat paddling teams.

Compared to those who chose the walking program, those who chose dragon boat paddling tended to have higher measures of strength and aerobic capacity, but the differences were not statistically significant. However, these results hint at the possibility that more physically fit cancer survivors may have been more likely to select the dragon boat paddling team. Further, 10% of those who chose the walking program indicated an aversion to the paddling program due to being “not strong enough” or “worried about their ability” to paddle.

The present study provides useful information to advance what is known about cancer survivors' choices in selecting between two different physical activity programs. The study population was comprised of both sexes and survivors of a diverse group of malignancies. To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine factors associated with selection between two group-based physical activity programs. The fact that one program was team-oriented (dragon boat paddling) and the other was not (walking program) adds to the value of the comparisons. However, the study has limitations to consider when drawing inferences. The study population was heterogeneous because physical activity programs were offered to survivors of any cancer type and at any point in the cancer trajectory from initial diagnosis to post-treatment. While one could argue the heterogeneity of the study population is a strength that enhances the external validity of the study findings, this heterogeneity could also be viewed as a weakness. Among our sample, the average time since diagnosis was 5.7 years with most participants not currently in active treatment. The choice between physical activity programs may differ according to where one is in the cancer survivorship continuum. However, studying survivor's choices along the treatment continuum is relevant because substantial proportions of survivors report wanting to start a physical activity program at different points along this continuum [14–17, 20]. As with the majority of physical activity studies, our inferences are limited to those who were healthy enough and interested enough to participate in an exercise program. Our results do not address the question of physical activity programs that could entice an unmotivated cancer survivor's participation in a physical activity program. Consequently, our results may not be representative of survivors experiencing more advanced stages of disease or lower functional status. Women, Caucasians, and breast cancer survivors represented the majority of the study participants, limiting more in-depth analyses of sex, ethnicity, and type of cancer.

Despite cancer survivors' high rate of reported interest in participating in physical activity programs, activity levels of most cancer survivors remain low during and after treatment [40–42]. The low rates of physical activity among cancer survivors may be impacted by the exercise choices available to choose from. Exercise adherence is a significant challenge even in the general population, making it important to learn more about the types of interventions that will be most successful in promoting exercise among cancer survivors. Of those who actually selected a program 96% went on to participate at all and attendance over 16 sessions was relatively high (74%) in this study population. Interestingly, adherence was significantly greater in those who participated in the dragon boat paddling team compared to the walking program. This preliminary finding suggests a potentially important characteristic of participating in dragon boat paddling is improved adherence. The extent to which this degree of adherence may generalize to cancer survivors in general is uncertain, as our study population was comprised of those who were already motivated enough to attend an information session about participating in a physical activity program, and so more likely to actually participate than a less selected population.

The relationship between cancer survivors' selection of a specific physical activity program and actual adherence to the program selected is an important topic. The present study was a non-randomized trial, so participants were allowed to choose between two available physical activity programs and then participate in the program of their choice. Previous studies have been carried out in which participants indicated a preference but then were randomized, regardless of preference, to a physical activity program. The results have been mixed concerning the importance of aligning physical activity program preferences with the actual program [43, 44]. In a study of breast cancer patients, those assigned to a physical activity program that matched their preferences had similar adherence to those not assigned to their preferred program [43]; interestingly, the overall program adherence in the previous study was in a similar range (67–76%) to the adherence in the current study. On the other hand, in a study of health club members, adherence was significantly better among those who received their preferred program compared to those who did not [44].

Conclusions

Two distinct physical activity programs were selected in approximately equal proportions, underscoring the importance of learning more about factors that affect cancer survivors' choices between types of physical activity programs. Cancer survivors who selected a team-oriented paddling program or a group walking program tended to be similar, except for the demographic characteristics of race and age. These results indicate that a menu of physical activity program options may be needed to optimize cancer survivors' physical activity levels.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Support for this project provided by the National Cancer Institute #1R03CA128482 (PI Dr. Carter).

REFERENCES

- 1.Courneya KS. Exercise interventions during cancer treatment: biopsychosocial outcomes. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2001;29:60–64. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto BM, Maruyama NC, Engebretson TO, Thebarge RW. Exercise participation, mood and coping in early-stage breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1998;16:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segar ML, Katch VL, Roth RS, Garcia AW, Portner TI, Glickman SG, Haslanger S, Wilkins EG. The effect of aerobic exercise on self-esteem and depressive and anxiety symptoms among breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimeo FC, Stieglitz RD, Novelli-Fischer U, Fetscher S, Keul J. Effects of physical activity on the fatigue and psychologic status of cancer patients during chemotherapy. Cancer. 1999;85:2273–2277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porock D, Kristjanson LJ, Tinnelly K, Duke T, Blight J. An exercise intervention for advanced cancer patients experiencing fatigue: a pilot study. J Palliat Care. 2000;16:30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz AL. Daily fatigue patterns and effect of exercise in women with breast cancer. Cancer Pract. 2000;8:16–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.81003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheema BS, Gaul CA. Full-body exercise training improves fitness and quality of life in survivors of breast cancer. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:14–21. doi: 10.1519/R-17335.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz AL, Mori M, Gao R, Nail LM, King ME. Exercise reduces daily fatigue in women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2000;33:718–723. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200105000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, Jones LW, Field CJ, Fairey AS. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1660–1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Quinney HA, Fields AL, Jones LW, Fairey AS. A randomized trial of exercise and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2003;12:347–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, Chan AT, Chan JA, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3527–3534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holick CN, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Titus-Ernstoff L, Bersch AJ, Stampfer MJ, Baron JA, Egan KM, Willett WC. Physical activity and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:379–386. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones LW, Courneya KS. Exercise counseling and programming preferences of cancer survivors. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:208–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.104003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karvinen KH, Courneya KS, Campbell KL, Pearcey RG, Dundas G, Capstick V, Tonkin KS. Exercise preferences of endometrial cancer survivors: a population-based study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29:259–265. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200607000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevinson C, Capstick V, Schepansky A, Tonkin K, Vallance JK, Ladha AB, Steed H, Faught W, Courneya KS. Physical activity preferences of ovarian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18:422–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karvinen KH, Courneya KS, Venner P, North S. Exercise programming and counseling preferences in bladder cancer survivors: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Jones LW, Reiman T. Exercise preferences among a population-based sample of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006;15:34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers LQ, Markwell SJ, Verhulst S, McAuley E, Courneya KS. Rural breast cancer survivors: exercise preferences and their determinants. Psychooncology. 2009;18:412–421. doi: 10.1002/pon.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones LW, Guill B, Keir ST, Carter K, Friedman HS, Bigner DD, Reardon DA. Exercise interest and preferences among patients diagnosed with primary brain cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers LQ, Malone J, Rao K, Courneya KS, Fogleman A, Tippey A, Markwell SJ, Robbins KT. Exercise preferences among patients with head and neck cancer: prevalence and associations with quality of life, symptom severity, depression, and rural residence. Head Neck. 2009;31:994–1005. doi: 10.1002/hed.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Shah P, Dunnington G, Hopkins-Price P. Exercise stage of change, barriers, expectations, values and preferences among breast cancer patients during treatment: a pilot study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16:55–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenzie DC. Abreast in a boat--a race against breast cancer. Cmaj. 1998;159:376–378. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell TL, Yakiwchuk CV, Griffin KL, Gray RE, Fitch MI. Survivor dragon boating: a vehicle to reclaim and enhance life after treatment for breast cancer. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28:122–140. doi: 10.1080/07399330601128445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unruh AM, Elvin N. In the eye of the dragon: women's experience of breast cancer and the occupation of dragon boat racing. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71:138–149. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Culos-Reed SN, Shields C, Brawley LR. Breast cancer survivors involved in vigorous team physical activity: psychosocial correlates of maintenance participation. Psychooncology. 2005;14:594–605. doi: 10.1002/pon.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane K, Jespersen D, McKenzie DC. The effect of a whole body exercise programme and dragon boat training on arm volume and arm circumference in women treated for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14:353–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ACSM's Health-Related Physical Fitness Assessment Manual (Paperback) 2nd Edition edn Williams & Wilkins; Lippincott: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noonan V, Dean E. Submaximal exercise testing: clinical application and interpretation. Phys Ther. 2000;80:782–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware JEJ, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Quality Metric Incorporated; Lincoln, RI: 1993. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware JEJ, Kosinski M. SF-36 Physical & Mental Health Summary Scales: A Manual for Users of Version 1. 2nd Edition edn Quality Metric Incorporated; Lincoln, RI: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairclough DL, Cella DF. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G): non-response to individual questions. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:321–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00433916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piper B, Lindsey A, Dodd M, Ferketich S, Paul S, Weller S. The development of an instrument to measure the subjective dimension of fatigue. In: Funk ET S, Champagne M, Wiese R, editors. Key aspects of comfort: Management of pain, fatigue, and nausea. Springer; New York, New York: 1989. pp. 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Yount SE, McGregor BA, Arena PL, Harris SD, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2004;23:16–23. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delaney C. The Spirituality Scale: development and psychometric testing of a holistic instrument to assess the human spiritual dimension. J Holist Nurs. 2005;23:145–167. doi: 10.1177/0898010105276180. discussion 168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilcox S, King AC, Brassington GS, Ahn DK. Physical activity preferences of middle-aged and older adults: a community analysis. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 1997;5:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myers AM, Weigel C, Holliday PJ. Sex- and age-linked determinants of physical activity in adulthood. Can J Public Health. 1989;80:256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Federation USDB 2010.

- 40.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Fairey AS. Managing the side effects of cancer and its treatments with exercise. American Journal of Medicine & Sports. 2003;5:132–136. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irwin ML, Ainsworth BE. Physical activity interventions following cancer diagnosis: methodological challenges to delivery and assessment. Cancer Investigation. 2004;22:30–50. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120027579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galvao DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention studies in cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:899–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Courneya KS, McKenzie DC, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Friedenreich CM, Ladha AB, Proulx C, Vallance JK, Lane K, et al. Moderators of the effects of exercise training in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2008;112:1845–1853. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson CE, Wankel LM. The effects of perceived activity choice upon frequency of exercise behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1980;10:436–443. [Google Scholar]