Abstract

Background

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is considering whether schizophrenia may warrant inclusion in their new “Compassionate Allowance” process, which aims to identify diseases and other medical conditions that invariably quality for Social Security disability benefits and require no more than minimal objective medical information. This paper summarizes evidence on the empirical association between schizophrenia and vocational disability. A companion paper examines the reliability and validity of schizophrenia diagnosis which is critically relevant for granting a long-term disability on the basis of current diagnosis.

Methods

This is a selective literature review and synthesis, based on a work plan developed in a meeting of experts convened by the National Institute of Mental Health and the SSA. This review of the prevalence of disability is focused on the criteria for receipt of disability compensation for psychotic disorders currently employed by the SSA.

Results

Disability in multiple functional domains is detected in nearly every person with schizophrenia. Clinical remission is much more common than functional recovery, but most patients experience occasional relapses even with treatment adherence, and remissions do not predict functional recovery. Under SSA’s current disability determination process, approximately 80% of SSDI/SSI applications in SSA’s diagnostic category of “Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders” are allowed, compared to around half of SSDI/SSI applications overall. Moreover, the allowance rate is even higher among applicants with schizophrenia. Many unsuccessful applicants are not denied, but rather simply are unable to manage the process of appeal after initial denials.

Discussion

Research evidence suggests that disability applicants with a valid diagnosis of schizophrenia have significant impairment across multiple dimensions of functioning, and will typically remain impaired for the duration of normal working ages or until new interventions are developed.

I. BACKGROUND

Over the past three years, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the Social Security Administration (SSA) have discussed how to improve SSA's disability determination process for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). SSA first approached the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in August, 2007, to invite NIH’s input in identifying diagnostic science that might let SSA improve their disability determination process. In particular, SSA has a new "Compassionate Allowance" process (http://www.ssa.gov/compassionateallowances/), under which SSI/SSDI applicants whose disability can be definitely established can be awarded benefits rapidly. The current list of Compassionate Allowance Conditions is available at http://www.ssa.gov/compassionateallowances/newconditions.htm.

SSA initially indicated that it was hoping to identify valid “tests” - e.g., genetic tests or diagnostic imaging - that would allow rapid and accurate identification of disorders that plausibly confer a priori eligibility for disability. Such diagnostic technology does not currently exist for major mental disorders. However, SSA indicated an interest in reviewing other types of scientific evidence that might help improve disability determinations. For instance, many mental disorders, including schizophrenia, which represents around eight percent of the adult recipients of SSI/SSDI, are associated with significant cognitive impairment, across multiple domains of functioning. Because cognitive impairment often results in functional disability, SSA expressed interest in identifying appropriately validated benchmarks of cognitive impairment, with the possibility that standardized measures of cognitive impairment could be part of a Compassionate Allowance determination for schizophrenia and other relevant mental and physical conditions.

In the particular case of schizophrenia, the disorder itself may warrant being included in SSA’s “Compassionate Allowance” process, provided that strong and reliable links can be established between disease related cognitive impairment and functional disability. That is, in this case documentation of a valid diagnosis of schizophrenia may be sufficient for SSA to award disability benefits. In this context, NIMH commissioned the authors – all internationally known experts in schizophrenia and psychiatric disability – to prepared two scientific review papers: the current paper, which examines the empirical association between schizophrenia and disability; and a second, related paper that examines the nature of schizophrenia diagnosis, including the reliability and validity of current diagnostic criteria; what data/information, methods, and expertise are needed for valid diagnosis; and the stability of the diagnosis over time. These papers were intended to help SSA determine how schizophrenia might warrant being included in SSA’s Compassionate Allowance program.

Nosology/Diagnosis

Schizophrenia as currently defined is an outgrowth of the original Kraepelinian concept of “Dementia Praecox” (Kraepelin, 1919). This nosological entity was defined as a condition with features of dementia (notable cognitive and functional impairments), an early age of onset compared to Alzheimer’s dementia, and a variety of associated features. These features include changes in emotional functioning, reduced drive and motivation, verbal communication abnormalities, unusual behavior, delusional thinking, and perceptual abnormalities experienced as hallucinations. Thus, from the first conceptualization of schizophrenia, the illness has been seen to be persistent, heterogenous, and associated with chronicity, and disability. The current definition of schizophrenia is actually quite similar (American Psychiatric Association, 1980).

This paper supports the argument that schizophrenia is a condition in which disability is an intrinsic part of the illness. Thus, it is not surprising that the majority of people with schizophrenia are receiving some disability compensation (Rosenheck et al., 2006). Further, formal or informal disability-related financial support is often provided soon after the diagnosis of schizophrenia: in a large sample of people recently diagnosed with schizophrenia, 80% were found to be either receiving disability compensation or to be completely dependent on a relative for financial support within 18 months of their initial contact (Ho et al., 1997).

In our companion paper we demonstrate that the current diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia can be applied with adequate validity. In this paper we focus on the disability associated with validly diagnosed schizophrenia.

Social Security Disability Criteria

In the United States, the principal sources of public disability insurance are the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) programs. Eligibility for SSDI and SSI is governed by regulations, the most relevant of which for this paper is SSA’s Listing of Impairments (shared by SSDI and SSI). For all mental disorders, disability claimants must meet specific criteria relating to the presence of specific symptoms, to support a medical cause of disability (“A” disability criteria). Claimants must also meet specific criteria relating to impairment in at least two out of four domains of functioning (“B” disability criteria). For schizophrenia, claimants may meet an additional set of criteria relating to chronic disorder-related impairment (“C” disability criteria), instead of or in addition to the “B” disability criteria.

Table 1 lists all three sets of disability criteria.

Table 1.

Social Security Rating Criteria for the Presence of Disability Associated with Psychotic Conditions.

| A. | Medically documented persistence, either continuous or intermittent, of one or more of the following:

|

| B. | Resulting in at least two of the following:

|

| C. | Medically documented history of a chronic schizophrenic, paranoid, or other psychotic disorder of at least 2 years' duration that has caused more than a minimal limitation of ability to do basic work activities, with symptoms or signs currently attenuated by medication or psychosocial support, and one of the following:

|

In the next sections, we summarize evidence regarding the prevalence of multiple domains of impairments in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. There are several elements of outcome in schizophrenia that are central to the issues of Social Security disability. They include presence and severity of disability, the prevalence of incomplete response of psychotic symptoms, the severity of cognitive impairments, the presence of persistent negative symptoms, and occurrence of symptomatic relapse in people who have been stabilized. Disability, impaired cognition, and negative symptoms are not responsive to current treatments (Harvey and Bellack, 2009) and are central features of the illness (Heinrichs and Zakzanis, 1998). There are substantial data to suggest that cognition and negative symptoms are the primary causes of disability in everyday activities (Bowie et al., 2008, Bowie et al., 2010, Leifker et al., 2009,)

II. Strategies for the Review of Data

This review is based on the directions established at a meeting of experts convened by the SSA and NIH in the summer of 2009. Following that meeting, a smaller task force was constituted to develop the content for two white papers and a series of topics were selected for literature searching. This literature search was not designed to be exhaustive, because the focus of the review is limited to literature relevant to the SSA guidelines for disability associated with psychosis.

After the literature search was completed, the current and companion papers were drafted, reviewed by NIH and SSA representatives, then submitted for comments to the original group of experts invited to the NIH/SSA meeting. The resulting white paper and its companion are the product of this process.

The reason for the initiation of this entire process was the concern arising from the SSA and advocacy groups that the likelihood receiving a disability determination after completion of the extensive review process was so great that the process may be both unnecessary and may serve to delay needed assistance. In addition, the bureaucratic process of application and review may be especially difficult for cognitively and socially impaired persons, impeding the receipt of compensation for potentially eligible recipients. As a result, we substantiated this need with a survey.

III. NATURAL HISTORY OF SSDI/SSI ADJUDICATION

As part of developing this paper, we obtained data on the “natural history” of SSDI/SSI applicants with schizophrenia, particularly regarding how their applications have been adjudicated. The SSA provided such data from their Disability Research Files, for SSDI/SSI applicants who applied within a diagnosis category that SSA calls “Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders”. SSA also provided parallel data for SSDI/SSI applicants overall, across all diagnoses. Data are for applicant cohorts from 1998–2007, with SSDI and SSI applicants pooled.

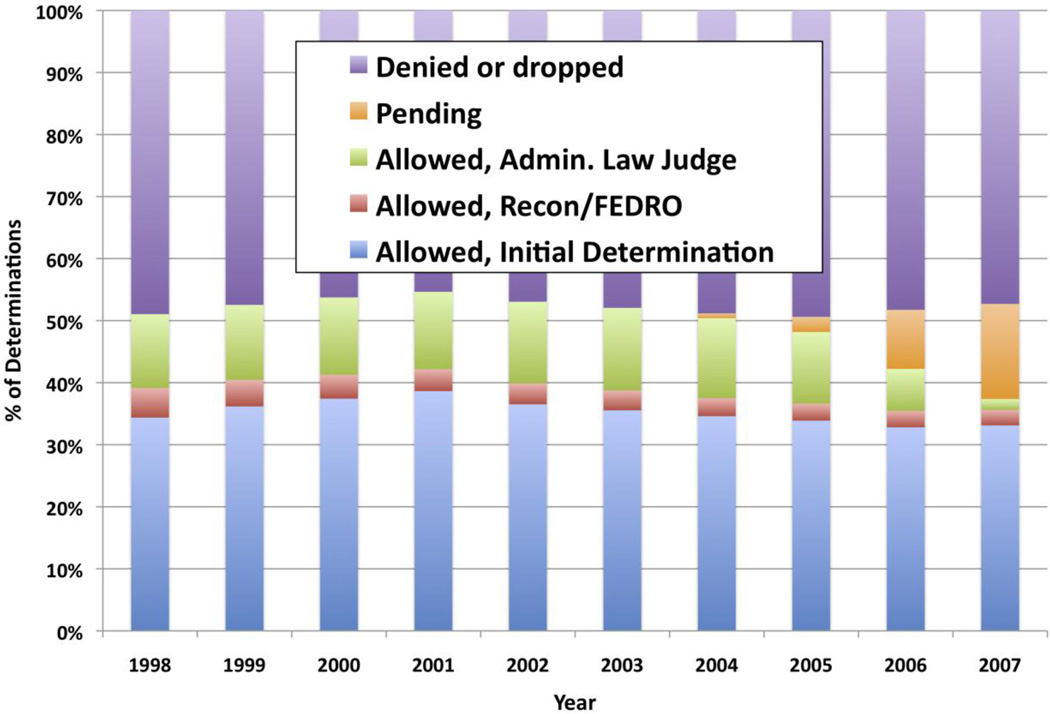

The total number of new applications, across all diagnosis categories, was 1,996,753 in 1998 and rose monotonically to 2,618,500 in 2007 (with the exception of 2004, which exceeded all other years with 2,681,689 applications). Figure 1 displays the fraction of each year’s cohort that was allowed, denied and/or dropped, or still pending at the time of the analysis. Overall, slightly more than half of applications were allowed (or pending, for the most recent years); the rate of denial ranged between 45.3% (2001) and 49.4% (2005). Most (~70%) of allowances were made at the point of initial determination; relatively few (<10%) were made at the point of first appeal; and the remainder (20–25%) were made at the point of second appeal.

Figure 1.

Disposition of SSI/SSDI Applicants - All Diagnoses

Source:SSA’s 2008 Disability Research File. Calculations conducted by SSA, and provided to the authors on July 13, 2010; reported with permission from SSA.

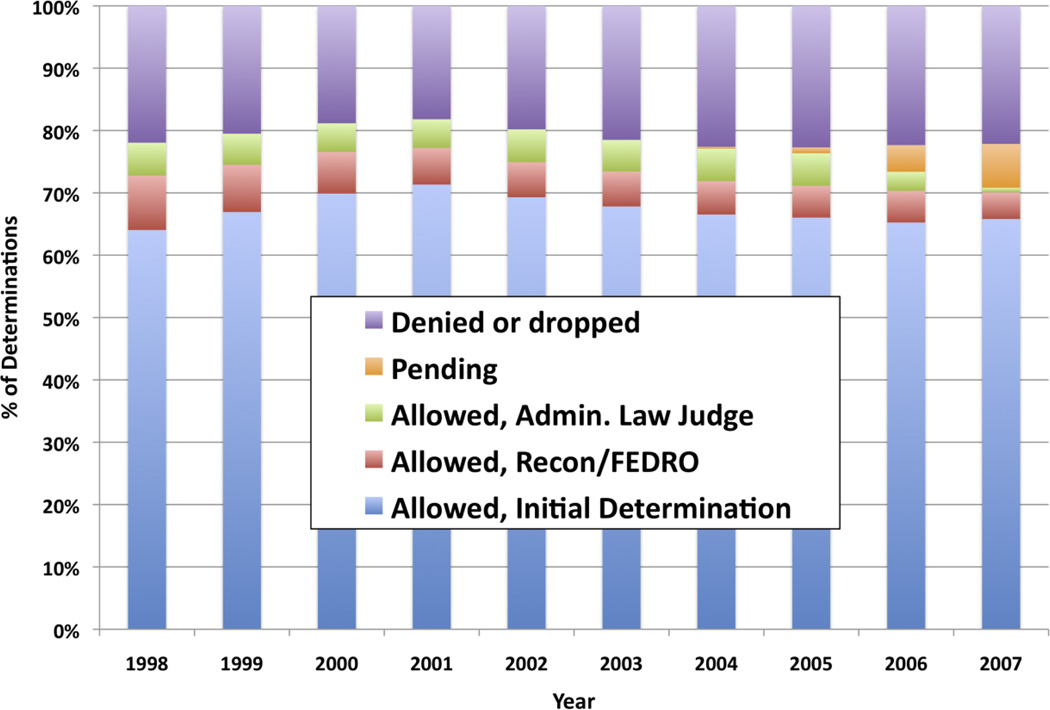

The total number of new applications in the “Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders” category was 45,807 in 1997, rose monotonically to 57,246 in 2004, and then declined monotonically to 50,585 in 2007. Figure 2 shows for each year the fraction of SSDI/SSI applications in this category that was allowed, denied/dropped, or pending at the time of analysis. In this diagnosis category, approximately 80% of applicants were awarded (or pending), and around 20% denied/dropped. Most (~80%) of determinations in favor of allowances were made at the point of initial review, with the rest roughly divided between the first and second points of appeal. Following this relatively high award rate, applications in the category “Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders” has accounted for around two percent of all SSDI/SSI applications, but around 3.5% of SSDI/SSI awards, between 1998 and 2007.

Figure 2.

Disposition of SSI/SSDI Applicants with Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders (SSA Diagnosis Code 2950)

Source:SSA’s 2008 Disability Research File. Calculations conducted by SSA, and provided to the authors on April 28, 2010; reported with permission from SSA.

These data indicate that most SSDI/SSI applications with “Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders” are ultimately allowed; moreover, they are allowed at a substantially higher rate, and earlier in the adjudication process, than SSDI/SSI applications overall. With regard to the 20% of applications in this category that are not allowed, the literature identifies several possible factors that we are currently unable to assess empirically. For instance, SSA’s diagnostic category includes applicants who do not claim to have schizophrenia. There is less scientific basis for a presumption of disability for other nonaffective psychotic disorders than for schizophrenia. Similarly, it seems very likely that some applicants in this category who claim to have schizophrenia would not actually meet the formal diagnostic criteria for this disorder, and thus fall outside the evidence we summarize in this paper. SSA’s electronic data systems do not currently enable analysis of the types or validity of diagnostic evidence submitted by applicants. It is quite possible, therefore, that the 80% final allowance rate for the SSDI/SSI category of “Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders” actually underestimates the rate for applicants with valid diagnoses of schizophrenia per se.

Finally, we note that it is difficult for us to assess how frequently applicants dropped initially unsuccessful SSDI/SSI applications, rather than pursuing them through all available appeals. This seems particularly relevant for applicants with schizophrenia, given the evidence described below that schizophrenia frequently impairs persistence and imposes various cognitive limitations that may impede disability application and appeal. The data reported by SSA do provide some indication that applicants with “Schizophrenia/Paranoid Functional Disorders” may drop initially unsuccessful applications more frequently than applicants overall. Specifically, of the approximately 20% of applications in this diagnostic category that are denied or dropped, only 10% (2% of all applications in this diagnostic category) were definitively denied, i.e., through initial adjudication and two rounds of appeal. Thus, 98% of applicants who persisted through two rounds of appeal eventually were awarded, in contrast to applicants overall of which closer to 15% (so around 6.5% of all applications) were definitely denied.

IV. SCHIZOPHRENIA AND EVERYDAY FUNCTIONING

Now that we have demonstrated that almost all applicants with schizophrenia who persist across multiple appeals eventually are awarded a disability, we now examine the evidence that this award has an empirical basis and should serve as the basis for a compassionate allowance. The majority of people with schizophrenia do not attain “normal” milestones in social functioning, productivity, residence, and self-care. Further, people with schizophrenia typically underperform compared to expectations based on the achievements of family members and their own functioning prior to diagnosis (Wilk et al. 2005). These impairments are present early in the illness (Reichenberg et al., 2009) and are clearly detectable at the time the diagnosis of schizophrenia is confirmed (Caspi et al., 2003). These impairments also are stable and are not produced in most cases by psychosis, per se, in that disability can be present even during periods when symptoms of psychosis are controlled (Keefe et al., 2006).

The functional outcomes of schizophrenia were essentially the same during the 50-year period prior to the introduction of antipsychotic medications as in the subsequent 30 years (Hegarty et al., 1994). An exception is extended inpatient treatment. In 1948, prior to the introduction of antipsychotic medications in the US, there were approximately 750,000 residents of long-stay psychiatric hospitals (Fisher et al., 2001) and now, 55 years after the introduction of these treatments, there are fewer than 1% of this number in long-stay institutional care. It is uncertain how much of this shift is attributable to medications, and/or to other factors such as changing public policies and societal norms. Moreover, functioning is poor among community-dwelling people who might have been hospitalized earlier, and the low rate of recovery from schizophrenia was estimated to be roughly the same in 1895 and 1985 (Hegarty et al., 1994). This suggests that management of psychosis rarely leads to true recovery, starting with the first episode (Robinson et al., 2004).

There are many ways to index disability. One way is to assess achievement of milestones, such as educational achievement, competitive employment and independent living. Poverty is a major correlate of schizophrenia, even in health care systems with little or no patient cost-sharing. For instance, nearly all of the 92,000 veterans with schizophrenia enrolled with the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in February, 2008, were either formally disabled and/or impoverished (Harvey and McClure, 2008). Furthermore, even this dismal statistic actually underestimates of the effect of schizophrenia related disability in the population as a whole, because of the exclusion from military service of people with early onset of psychosis. VA populations have been shown to be less disabled than non-veteran samples (Harvey et al., , 2000).

Cognitive Functioning

Cognitive impairments are the most consistent determinant of deficits in everyday functioning in schizophrenia, as demonstrated by the results of two large-scale meta-analyses (Green, 1996, Green, 2000). These impairments are present across the course of illness, occurring in the same time frame as disability, and are minimally affected by antipsychotic medications (Harvey, and Keefe, 2001). Especially relevant here is the prevalence of cognitive impairment; or, conversely, the low prevalence of “neuropsychological normality” in people with schizophrenia. If “neuropsychological normality” is defined as performance on a neuropsychological assessment battery greater than one standard deviation below the “healthy” mean, the number of cases across studies is about 20–30 at most% (Wilk et al., 2005, Reichenberg et al., 2009, Kremen et al., 2000, Mojtabai et al., 2000). This contrasts to 83% of the healthy population scoring at this level. The level of impairment seen, uncorrected for other factors, is consistent across studies of stabilized first-episode patients (Saykin et al., 1994, Reichenberg et al., 2009), as well as among people with chronic schizophrenia (Heaton et al., 2001). Although statistics about this are not available, the minority of people with schizophrenia diagnoses who do not have serious cognitive limitations and related functional disability are presumably less likely to apply for disability support (tending to self-select out of the applicant pool described above). As such, they arguably are of little relevance to the appropriateness of “Compassionate Allowance” status for disability applicants with schizophrenia.

Beyond the issue of cognitive impairment at any point in time, there is the question of how cognition is affected before onset of psychosis and hence is present at the first episode. Here, research suggests that schizophrenia is universally associated with reduced cognitive performance even during childhood, based on data such as IQ scores (Woodberry et al., 2008), other academic achievement scores (Palmer et al., 1997), or aspects of cognition that are unassociated with decline, such as reading ability (Harvey et al., 2000). Further, evidence for this type of cognitive limitation is also reliably observed even among patients whose overall performance is in the normal range (Wilk et al., 2005). These findings suggest that all individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia demonstrate have experienced limitations in cognitive functioning, relative to their own prior capacity and to normative standards.

Drive and Motivation

In addition to disease related cognitive impairments, schizophrenia is notable for the presence of reduced social and vocational motivation (Carpenter 1994). As many as 40% of people with schizophrenia are seen to have persistent reductions in social motivation and hedonic (pleasure-related) capacity (Kirkpatrick et al., 2001). These impairments are associated with reductions in the propensity to function in everyday settings (Tamminga et al., 1998). In addition, impairments in social outcomes in schizophrenia are highly correlated with reductions in social drive, which has been found to be more important for the prediction of social functioning than cognitive impairments or social competence/skills (Leifker et al., 2009).

As is the case with cognition in schizophrenia, these impairments in motivation and drive are not responsive to current treatments for the illness. They are also not the consequence of other aspects of the illness or treatments for the illness. These are commonly described as “primary negative symptoms” or “deficit” symptoms. In long-term studies of people with schizophrenia, the presence of severe negative symptoms was associated with long-term worsening in functioning and permanent disability (Fenton and McGlashan, 1991). Moreover, reduced drive does not represent a voluntary wish for inactivity or avoidance of work or social engagement; rather, these impairments result from primary defects in the brain systems supporting motivated behavior and reward reinforcement (Tamminga et al., 1992).

Activities of Daily Living

Schizophrenia is associated with impairment in the ability to perform activities of daily living, including self-care activities such as instrumental activities like financial management, shopping, cooking, cleaning, and managing medications and transportation.

Independent living

In the US, approximately 25–40% of people with schizophrenia are living independently and are responsible for paying their bills (Leung et al., 2008). However, this level of apparent independence in functioning may not have been possible in the absence of disability compensation; for instance, in two separate samples, over 75% of the independently residing patients received disability compensation (Harvey et al., 2009). Similarly, in a two-year follow-up of people with schizophrenia after their first episode, only those who were receiving disability compensation or were supported by their families were living independently (Ho et al., 1998). Deficits in cognition and functional capacity are also associated with level of residential independence (Mausbach et al., 2007, Mausbach et al., 2010).

Although a number of studies have shown that targeted interventions may improve certain functional skills (Patterson et al., 2006), it has yet to be shown that these changes lead to sustained improvements in residential status. Thus, it seems likely that these impairments are substantial, are present at of before the time of the first episode, and are not responsive to current treatments.

Health and medication management

People with schizophrenia typically have several co-morbid medical problems and a reduced life expectancy. In the baseline assessment of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) treatment study, over 50% of participants had multiple medical problems (McEvoy et al., 2005), which were found to generally be untreated (Nasrallah et al., 2006). These findings are consistent with a large body of data suggesting that people with schizophrenia have worse medical outcomes, often due to lack of appropriate medical care or interventions (Druss et al., 2001).

Management of medication is a major issue for people with schizophrenia. It has been shown that some cognitive deficits predict impairments in medication management (Jeste et al., 2003) and that failures to refill prescriptions are common (Weiden et al., 2004), that patients take incorrect doses, and generally fail to take medications as directed (Mahmoud et al., 2004). Medication management deficits are one of the contributors to relapse in people with schizophrenia.

Driving, cooking, travel, and shopping

Research suggests that only a minority of people with schizophrenia are fully capable of performing important self-care tasks. For instance, follow-up studies at the NIMH clinical research center found that only 20% of patients seen there were performing self-care activities (Breier et al., 1991). In another study, only 50% of people with schizophrenia had a valid driver’s license, and approximately 40% reported that they currently were drivers (Palmer et al., 2002). These numbers, collected on a sample in Southern California, contrast to 96% of a sample of demographically similar healthy controls. In that study, the best predictors of not being a driver were the overall severity of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments.

While existing data do not allow for direct assessment of activities such as cooking, travel, and shopping, a world-wide study of over 17,000 patients reported marked impairments in these domains (Karagianis et al., 2009). Further, the studies that examined the determinants of these impairments implicated cognitive impairments, sometimes more saliently than negative symptoms, as predictors.

Social Functioning

People with schizophrenia manifest multiple social impairments. They infrequently achieve traditional social milestones such as marriage or equivalently stable relationships (Harvey et al., 2009); they often have reduced social networks (Patterson et al., 1997); and their general patterns of socially oriented activities are restricted. Further, their social skills or abilities (“competence”) typically are impaired (Patterson et al., 2001) and these impairments in social competence may lead to an adverse impact on other aspects of functioning, such as employment (Evans et al., 2004).

An additional feature of social impairment in people with schizophrenia involves socially disruptive behavior, such as socially inappropriate comments, inappropriate or intrusive requests, impairments in tone or volume or speech, and impairments in judging appropriate interpersonal distance (Wykes and Stuart, 1986). While some of these impairments may fall under the “A” criteria of grossly disorganized behavior (e.g., walking in the middle of a busy street while screaming), most are not grossly disorganized, but may be inappropriate and make others uncomfortable. When the person who is rendered uncomfortable is a supervisor, co-worker, or customer, such problems can lead to job terminations (Becker et al., 1998).

A final general feature of social outcomes in schizophrenia is social motivation. As described above, there are particular reductions in sensitivity to social reinforcement, in the ability to experience pleasure, and in the interest to engage in activities involving other people.

Concentration, Persistence, and Pace

While there are many forms of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, those involving attentional processes and speed of information processing are among the most prevalent and disabling (Dickinson et al., 2004). Other research data have implicated substantial impairments in “episodic memory,” the ability to learn information and to retain it after a delay (Saykin et al., 1991). As noted above, virtually every individual with schizophrenia likely manifests such impairments when compared to expected or pre-illness levels of functioning. Concentration and persistence are often referred to as “vigilance”, which can also be referred to as “sustained attention”. This is defined as the ability to sustain effort and attention in an adaptive manner (Bryson and Bell, 2003).

People with schizophrenia also have notable impairments in “working memory” (Cannon et al., 2005), which describes the ability to keep information in conscious awareness and manipulate it over short periods of time. Finally, maintenance of pace is often referred to as “processing speed”. Processing speed is measured through tests of the ability to rapidly and efficiently complete various tests of coding, sorting, or matching stimuli (Dickinson et al., 2007) and such tests have been the cornerstone of assessments of vocational potential for decades (Gold et al., 2002). Processing speed is the single largest deficit seen in people with schizophrenia, based on large-scale meta-analyses (Dickinson et al., 2004), and is thought to underlie poor performance on other cognitive tests and global functional deficits in people with schizophrenia (Dickinson and Harvey, 2009).

Critically, cognitive impairments are present in the same severity at the time of the first episode of illness as among people who have had schizophrenia for many years (Mesholam-Gately, et al., 2009), not developing over time as a function of chronicity. Based on our assessment of the scientific literature, reports of “spontaneous improvement” in cognitive performance among people with schizophrenia either reflect changes that are clinically/substantively insignificant, or they may reflect inaccurate diagnosis.

V. SCHIZOPHRENIA TREATMENT RESPONSE

Persistent Symptoms Despite Treatment

While the vast majority of people with schizophrenia manifest a clinical response, including remission of symptoms, at the time of their first treatment with antipsychotic medications (Robinson et al., 2004), non-response develops over time. In longitudinal studies, the rate of clinical response drops from approximately 90% to 65% across the first two relapses (Leiberman et al., 1996). The rate of minimal response of psychotic symptoms to treatment appears to be approximately 30% (Kane et al., 1988), while about 40% of people with schizophrenia experience sustained clinical remission albeit not accompanied by functional recovery (De Hart et al., 2007). Persistent psychotic symptoms are known to interfere with employment, as individuals with schizophrenia who obtain and subsequently are discharged from a job are often psychotic at the time of their job loss.

Schizophrenia and Psychotic Relapse

Antipsychotic medication reduces the severity of psychotic symptoms in most people with schizophrenia, but has a minimal therapeutic effect on the cognitive impairments that are more closely linked to disability (Harvey and Keefe, 2001). In fact, across studies as many as 40% of people with schizophrenia can experience clinical remission (absence or minimal presence of all of the criterion “A” symptoms described above when treated successfully with antipsychotic medications). While some cross-sectional studies have suggested that clinical remission is associated with adequate performance of functional skills (De Hart et al., 2007), longitudinal studies have suggested that development or maintenance of clinical remission rarely correlates with cognitive improvements or improvements in primary negative symptom pathology which should predict functional changes (Buckley et al., 2007).

Regardless of the ability of medication to promote clinical remission, it is clear that the majority of people with schizophrenia who achieve remission subsequently experience relapse. This relapse is sometimes associated with treatment non-adherence. Non-adherence and partial adherence are extremely common and most people with schizophrenia experience periods of time when they are either completely or partially non-adherent. Relapse in non-adherent cases occurs at a rate of slightly more than 10% per month (Robinson et al., 1999).

Levels of non-adherence are likely no higher in people with schizophrenia than in individuals with medical conditions such as hypertension (Christensen et al., 2010). However, in schizophrenia the consequences of non-adherence are more immediate and obvious. Analyses of the causes of non-adherence in schizophrenia have suggested that illness-related causes such as limited clinical response to treatment, cognitive impairments, and unawareness of illness account for the majority of non-adherence (Velligan et al., 2009). In conclusion, relapse should be expected in the majority of people with schizophrenia, including some who are adherent and even among those who voluntarily accept long acting injectible medications (Conley et al., 2003).

SSA’s disability criteria in Subsection 12.03 of the Listings also refer to the concept of “repeated and lengthy decompensations”. Decompensation is a holdover term from previous conceptions of schizophrenia, wherein worsening psychotic symptoms was theoretically believed to be a failure of defense mechanisms. We have referred to these concepts above as “exacerbation,” which refers to worsening in symptoms, and relapse, which means substantial worsening. Patients who experience repeated exacerbation fall into two broad groups. The first group of patients includes those who have reasonable symptom control and subsequently worsen. The second group is the subset of people with schizophrenia whose symptoms fail to respond meaningfully to antipsychotic treatments. This is relatively rare at the time of first episode; as noted above, over 90% of the patients respond to antipsychotic treatment in their first year of treatment. But the non-response rate rises substantially over time, with at least one-third of people with schizophrenia developing treatment resistance within five years of illness onset (Lieberman et al., 1996). In the first episode study just mentioned, only five of over 100 patients had not experienced a relapse of their symptoms within five years (Robinson et al., 1999).

Thus, even patients with excellent initial treatment response routinely relapse. Indeed, after the first episode, the majority of people with schizophrenia are experiencing consistent psychotic symptoms, even if they are not severe enough to lead to acute psychiatric admissions. These people are chronically symptomatic and it has been shown that even low levels of on-going psychotic symptoms can be associated with impairments in real world functioning (Mohamed et al., 2008). Further, the majority of people with schizophrenia experience more than one relapse, indicating that repeated exacerbations should be viewed as an intrinsic part of the illness, and not limited to a subset of people with schizophrenia (let alone a readily identifiable subset).

Persistent or Recurrent Impairments Despite Initially Successful Treatment

This section focuses on the persistence of illness and functional impairment over extended periods despite initial treatment success. There are three components to these elements of thee SSA disability criteria. The first and second concern vulnerability to relapse: repeated relapses after clinical stabilization or vulnerability to relapse on the basis of inability to tolerate environmental demands. The third criterion, inability to live outside structured residential settings, is not related to relapse but rather to self-care and everyday living skills.

Repeated Exacerbations

This criterion appears related to criterion B4, but specifies that initial clinical stabilization must precede these episodic periods of decompensation. Given the data reviewed above regarding decompensation in schizophrenia, repeated decompensation and/or chronic levels of ongoing psychotic symptoms will be a feature of most individuals with schizophrenia, even with excellent initial treatment response.

Supported Residential Status

As reviewed above, one of the components of impaired everyday living skills in schizophrenia is impairment in the ability to live in an independent manner. As noted above, estimates of the rates of non-independent living range from 50% to 75% across different studies. The review above shows that the need for supported living is related to skills deficits and not reduced motivation or other factors. The vast majority of patients who are able to live outside of supported residential status are doing so with the assistance of disability compensation (McEvoy et al., 2005) , hence suggesting that this residential positive outcome is a consequence of disability compensation and is not likely to be effected until after compensation is awarded.

Supported Employment

Supported employment is an evidence-based process by which individuals with severe mental illness who are seeking employment are assisted in the process of obtaining and maintaining productive work. These processes include intensive interviewing, job coach accompaniment to interviews and work, and intensive support. Large scale multi-site randomized trials (Cook et al., 2005) have shown statistically significant effects of supported employment.

These results suggest that supported employment is beneficial for a portion of patients who desire to work and are not limited by other impairments or co-morbidities. It has been reported that patients with bipolar disorder are more likely to achieve steady work success than people with schizophrenia (Bush et al., 2009), but supported employment is regarded as an evidence-based intervention for people with schizophrenia.

Although supported employment is an intervention improves functional outcomes for a subset of patients with schizophrenia, it seems unlikely that supported employment interventions will eliminate the need for a compassionate allowance. This is because most patients with schizophrenia have no access to supported employment interventions and some of these intervention programs have a prerequisite of health insurance coverage, which again is associated with the receipt of SSA or SSD.

Prevalence and Correlates of Independent Functioning

Studies of recovery from the first episode of illness have estimated rates of adequate functioning across social and vocational domains of less than 15% after 5 years of illness (Robinson et al., 2004); moreover, such recoveries generally occurred quite early in the five-year period. It is likely that individuals who manifest functional recovery with current treatments are exceptions in other ways, such as having extremely supportive or resource-rich environments, and such people may correspondingly be unlikely to seek disability benefits.

VI. DISCUSSION

There are several conclusions from the data reviewed in this paper. Disability in multiple functional domains is detected in nearly every patient with schizophrenia. Clinical remission is rare and unstable, with most patients experiencing regular relapse even with adherence to oral or long-acting injectible medications. Symptomatic remissions do not predict functional recovery, and functional deficits are associated very poor occupational and residential outcomes. Reductions in motivation and reward sensitivity are common in schizophrenia, but these do not indicate that patients with schizophrenia make a volitional decision not to seek or sustain employment.

Our companion paper shows that the diagnosis of schizophrenia is persistent after the first episode, and that conclusion interfaces with the current conclusions. Schizophrenia is persistent from time of the first episode, and individuals who meet the duration criteria specified by the SSA will likely be disabled for the duration of typical working ages, at least pending the development and adoption of substantially more effective treatments for schizophrenia.

An Important Caveat

Although our literature review suggests that disability is an intrinsic feature of schizophrenia, we do not suggest that recovery is impossible. On the contrary, it is likely that the early receipt of disability compensation and related insurance benefits would facilitate recovery or at least optimal functional outcomes for the individual patient. There are several reasons that this is true. First, the availability of treatment early in the course of the illness is likely to lead to fewer relapses and reduced deterioration in the early course. Second, financial benefits that facilitate suitable residential functioning and diet (as well as the ability to pay for medications) are also likely to lead to increased potential for long term recovery or optimal functioning in people with schizophrenia. Third, insurance coverage may provide access to other services such as supported employment that may reduce morbidity. Finally, the ability to consistently receive mental health treatment services, facilitated by Medicare insurance, is a clear benefit compared to relying on our current fractured mental service delivery system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government. This was the result of a committee effort including other individuals not directly involved as authors, including Robert Drake, MD, Susan McGurk, PhD, and Howard Goldman, MD.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported via contract by the National Institute of Mental Health.

SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: The authors would like to thank Feea Leifker for her literature searching for this project.

A meeting convened by the NIMH served as the basis for this paper. All individuals who attended that meeting contributed to the discussions, but the writing of the paper was completed by the current authors. See special acknowledgement to Ms. Leifker.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

In the past 12 Months, the authors have the following activities to Disclose:

Dr. Harvey has received consulting fees for Abbott Labs, Boeheringer Engelheim, Genentech, Johnson and Johnson, Pharma Neuroboost, Roche Pharma, Shire Pharma, Sunovion Pharma, and Takeda Pharma.

Dr. Carpenter has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Lundbeck Pharma, and Merck and Company.

Dr. Green has been a Consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Cypress Bioscience, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sunovion, Sanofi-aventis, Takeda, Teva and been a Speaker for Janssen-Cilag, Otsuka, and Sunovion .

Dr. Gold has served as a consultant to Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck and Company, and Pfizer Pharma.

Drs. Heaton and Schoenbaum have no activities to disclose.

Conflict Of Interest Statement.

Contributions of the Authors.

All authors contributed equally to this review paper, through a series of conference calls and multiple revisions of this paper.

Contributor Information

Philip D. Harvey, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Robert K. Heaton, UCSD Medical Center.

William T. Carpenter, Maryland Psychiatric Research Institute.

Michael F. Green, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

James M. Gold, Maryland Psychiatric Research Institute.

Michael Schoenbaum, National Institute of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR, Xie H, Dain BJ, Harrison K. Job terminations among people with severe mental illness participating in supported employment. CommMent Health J. 1998;34:71–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1018716313218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Mausbach BT, Thornquist MH, et al. Prediction of Real World Functional Disability in Chronic Mental Disorders: A Comparison of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Am JPsychiat. 2010;167:1116–1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, et al. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measure. Biol Psychiatr. 2008;63:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D. National institute of mental health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia. Prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:239–246. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson G, Bell MD. Initial and final work performance in schizophrenia: cognitive and symptom predictors. J NervMent Dis. 2003;19:87–92. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000050937.06332.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PF, Harvey PD, Bowie CR, Loebel A. The relationship between symptomatic remission and neuropsychological improvement in schizophrenia patients switched to treatment with ziprasidone. Schizophr Res. 2007;94:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush PW, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Haslett WR. The long-term impact of employment on mental health service use and costs for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1024–1031. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Glahn DC, Kim J, Van Erp TG, Karlsgodt K, Cohen MS, et al. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity during maintenance and manipulation of information in working memory in patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2005;62:1071–1080. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT. The deficit syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:327–329. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Rabinowitz J, Kaplan Z, Knobler H, et al. Cognitive performance in schizophrenia patients assessed before and following the first psychotic episode. Schizophr Res. 2003;65:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, CHristrup LL, Fabricius PE, Chrostowska M, Wronka M, Narkiewicz K, et al. The impact of electronic monitoring and reminder device on patient compliance with antihypertensive therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2010;28:194–200. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328331b718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley RR, Kelly DL, Love RC, McMahon RP. Rehospitalization risk with second-generation and depot antipsychotics. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2003;15:23–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1023276509470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Leff HS, Blyler CR, Gold PB, Goldberg RW, Mueser KT, et al. Results of a multisite randomized trial of supported employment interventions for individuals with severe mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2005;62:505–512. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M, van Winkel R, Wampers M, Kane J, van Os J, Peuskens J. Remission criteria for schizophrenia: Evaluation in a large naturalistic cohort. Schizophr Res. 2007;92:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Harvey P. Systemic hypotheses for generalized cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a new take on an old problem. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:403–414. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Iannone VN, Wilk CM, Gold JM. General and specific cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. BiolPsychiatr. 2004;55:826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Ramsey ME, Gold JM. Overlooking the obvious: a meta-analytic comparison of digit symbol coding tasks and other cognitive measures in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2007;64:532–542. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2001;58:565–572. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD, Bond GD, Meyer PD, Kim HW, Lysaker PH, Gibson PJ, et al. Cognitive and clinical predictors of success in vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton WS, McGlashan TH. Natural history of schizophrenia subtypes, II: positive and negative symptoms and long-term course. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1991;48:978–986. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810350018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WH, Barreira PJ, Geller JL, White AW, Lincoln AK, Sudders M. Long stay patients in state psychiatric hospitals at the end of the 20th century. PsychiatrServ. 2001;52:1051–1056. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, Dixon LB, Lehman AF. Cognitive correlates of job tenure among patients with severe mental illness. Am J Psychiat. 2002;159:1395–1402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Bellack AS. Toward a terminology of functional recovery in schizophrenia: Is functional remission a viable concept? Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:300–306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Helldin L, Bowie CR, Heaton RK, Olsson AK, Hjarthag F, et al. Performance-based measurement of functional disability in schizophrenia: A cross-national study in the United States and Sweden. Am J Psychiat. 2009;166:821–827. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Jacobsen H, Mancini D, Parrella M, White L, Haroutunian V, et al. Clinical, cognitive and functional characteristics of long-stay patients with schizophrenia: A comparison of VA and state hospital patients. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Keefe RSE. Interpreting studies of cognitive change in schizophrenia with novel antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatr. 2001;158:176–184. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, McClure MM. Data accessed from VA Central office records. 2008 Feb [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Moriarty PJ, Friedman JI, White L, Parrella M, Mohs RC, et al. Differential preservation of cognitive functions in geriatric patients with lifelong chronic schizophrenia: less impairment in reading scores compared to other skill areas. Biol Psychiatr. 2000;47:962–968. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV. Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2001;58:24–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty JD, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, Waternaux C, Oepen G. One hundred years of schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of the outcome literature. Am J Psychiatr. 1994;151:1409–1416. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–444. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho BC, Andreasen N, Flaum M. Dependence on pubic financial support early in the course of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Serv. 1997;48:948–950. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.7.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho BC, Nopoulos P, Flaum M, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Two-year outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: predictive value of symptoms for quality of life. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1196–1201. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste SD, Patterson TL, Palmer BW, Dolder CR, Goldman S, Jeste DV. Cognitive predictors of medication adherence among middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer HY. Clozapine for the treatment resistant schizophrenia: a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagianis J, Novick D, Penecak J, Haro JM, Dossenbach M, Treuer T, et al. Worldwide-Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes(W-SOHO): baseline characteristics of pan-regional observational data from more than 17,000 patients. Int J ClinPrac. 2009;63(11):1578–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RSE, Bilder RM, Harvey PD, Davis SM, Palmer BW, Gold JM, et al. Baseline neurocognitive deficits in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2033–2046. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Ross DE, Carpenter WT. A separate disease within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:165–171. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin E. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia. Edinburgh: E.S. Livingstone; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Toomey R, Tsuang MT. The paradox of normal neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:743–752. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifker FR, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. The determinants of everyday outcomes in schizophrenia: Influences of cognitive impairment, clinical symptoms, and functional capacity. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung WW, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Functional implications of neuropsychological normality and symptom remission in older outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. J IntNeuropsycholSoc. 2008;14:479–488. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, ALvir JM, Koreen A, Geisler S, Chakos M, Sheitman B, et al. Psychobiologic correlates of treatment response in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:13S–21S. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00200-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud RA, Engelhart LM, Janagap CC, Oster G, Ollendorf D. Risperidone versus conventional antipsychotics for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder : symptoms, quality of life and resource use under customary clinical care. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:275–286. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Pulver AE, Depp CA, Wolyniec PS, Thornquist MH, et al. Relationship of the Brief UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B) to multiple indicators of functioning in people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. BipolDisord. 2010;12:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, Nasrallah HA, Davis SM, Sullivan L, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:315–336. doi: 10.1037/a0014708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Swartz M, Stroup S, Lieberman JA, Keefe RS. Relationship of cognition and psychopathology to functional impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatr. 2008;165:978–987. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Bromet EJ, Harvey PD, Carlson GA, Craig TJ, Fennig S. Neuropsychological differences between first admission schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, Stroup TS, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Evans JD, Patterson TL, Golshan S, et al. Heterogeneity in functional status among older outpatients with schizophrenia: employment history, living situation, and driving. Schizophr Res. 2002;55:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, Kuck J, Braff D, Harris MJ, et al. Is it possible to be schizophrenic and neuropsychologically normal? Neuropsychology. 1997;11:437–447. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Mausbach BT, McKibbin C, Goldman S, Bucardo J, Jeste DV. Functional adaptation skills training (FAST): A randomized trial of psychosocial intervention for middle-aged and older patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Davidson K, Jeste DV. Social skills performance assessment among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Shaw WS, Halpain M, Moscona S, Grant I, et al. Self-reported social functioning among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizopr Res. 1997;27:199–210. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Harvey PD, Bowie CR, Mojtabai R, Rabinowitz J, Heaton RK, et al. Neuropsychological function and dysfunction in schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:1022–1029. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, et al. Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM. Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatr. 2004;161:473–479. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins D, et al. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiat. 2006;163:411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozeley D, Mozeley LH, Resnick SM. Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: Selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1991;48:618–623. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniack P, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1994;51:124–131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020048005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Buchanan RW, Gold JM. The role of negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia outcome. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(Suppl 3):S21–S26. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199803003-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Thaker GK, Buchanan R, Kirkpatrick B, Alphs, et al. Limbic system abnormalities identified in schizophrenia using positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose and neocortical alterations with deficit syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:522–530. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820070016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, Scott J, Carpenter D, Ross R, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, Locklear J. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. PsychiatrServ. 2004;55:886–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk CM, Gold JM, McMahon RP, Humber K, Iannone VN, Buchanan RW. No, it is not possible to be schizophrenic yet neuropsychologically normal. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:778–786. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:579–587. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Stuart E. The measurement of social behavior in psychiatric patients: and assessment of the reliability and validity of the SBS schedule. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;148:1–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.148.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]