Abstract

The development of response inhibition was investigated using a computerized go/no-go task, in a lagged sequential design where 376 preschool children were assessed repeatedly between 3.0 and 5.25 years of age. Growth curve modeling was used to examine change in performance and predictors of individual differences. The most pronounced change was observed between 3 and 3.75 years. Better working memory and general cognitive ability were related to more accurate performance at all ages, but relations with speed changed with age, where better cognitive skills were initially related to slower responding, but faster responding at later ages. Boys responded more quickly and were more accurate on go trials, whereas girls were better able to withhold responding on no-go trials.

When working toward a goal, the most available or obvious course of action may not be the best one. Inhibitory processes play a key role in adaptive behavior under these circumstances, where suppressing a prepotent response allows activation of a less available, but more appropriate, response. This cognitive skill is most commonly referred to as response inhibition (Nigg, 2000), and the preschool period, from age three to six years, has been identified as key in its emergence (see Garon, Bryson, & Smith, 2008, for a review).

Most studies of preschool response inhibition have utilized cross-sectional comparisons of children in different age groups (e.g., Carlson, 2005; Diamond & Taylor, 1996; Dowsett & Livesey, 2000; Espy, Bull, Martin, & Stroup, 2006; Jones, Rothbart, & Posner, 2003; Klenberg, Korkman, & Lahti-Nuuttila, 2001; Tsujimoto, Kowajima, & Sawaguchi, 2007). In contrast, relatively little information is available concerning within-person growth of response inhibition, and factors that contribute to individual differences in growth. Among the few existing longitudinal studies, many have used different measures to assess response inhibition at different ages, permitting assessment only of stability in rank order and not within-child patterns of growth (e.g., Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000). Others have examined response inhibition in atypically developing populations rather than delineating variation in normative development (e.g., Altemeier, Abbott, & Berninger, 2008; Berlin, Bohlin, & Rydell, 2003). The overarching goal of the present study was to address this gap in the literature by elucidating the development of response inhibition across the preschool period using a single instrument, the go/no-go task, in order to characterize developmental trajectory of this emerging ability and its variation by identifying systematic predictors of children’s initial status and rate of growth.

The Development of Response Inhibition

The ability to inhibit a prepotent response emerges in infancy, as the inhibitory control of eye movements is possible as early as 4 months of age (Johnson, 1995), and inhibitory control of reaching emerges later in the first year (Diamond, 1990). It is not until the fourth year, concomitant with language development and better representation of abstract or arbitrary rules, that children can complete tasks more similar to those used to assess response inhibition in adults. Across the preschool period, children show improvements in the ability to suppress a motor response such as a button press (Carver, Livesey, & Charles, 2001; Simpson & Riggs, 2006) or verbal response (Espy et al., 2006), and the ability to produce a response that conflicts with prepotent tendencies, for example in Stroop-like tasks incorporating stimuli that afford multiple responses (Pasalich, Livesey, & Livesey, 2010) or in tapping or gesturing games based on Luria’s pioneering work, where the prepotent response tendency is to imitate the examiner’s actions (Diamond & Taylor, 1996). Response inhibition does not reach maturity until early adolescence, as evidenced by stable task performance with age (at age 12, in Levin et al., 1991; at age 14, in Luna, Garver, Urban, Lazar, & Sweeney, 2004). This timeline is consistent with findings that neural circuits that subserve response inhibition continue to develop into adolescence (Giedd et al., 1999).

Individual Differences in Response Inhibition

Cross-sectional studies have revealed normative age-related improvements in response inhibition, but children within an age group vary considerably in inhibitory capacity and, most likely, in their rate of change. Characterizing this variation is important for gaining a more complete understanding of response inhibition. As well, these early differences in response inhibition likely portend later differences in outcome, and thus characterizing the variables that contribute to this variation is important in identifying risk pathways. Deficits in response inhibition have been implicated in many behavioral disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Berlin et al., 2003) and childhood bipolar disorder (Leibenluft et al., 2007); as such, identification of factors that account for variability in children’s individual trajectories of response inhibition growth can provide insight into risk for problematic developmental pathways.

There is considerable evidence that girls are more capable of response inhibition than boys, evident as early as the second year (Kochanska et al., 2000). Across the preschool period, and across many different measures of response inhibition, boys tend to make more errors, reflecting poor response inhibition (Berlin et al., 2003; Carlson & Wang, 2007; Klenberg et al., 2001; although for exceptions finding no sex differences see Carlson, Moses & Breton, 2002; Davidson, Amso, Anderson, & Diamond, 2006). Wiebe, Espy, and Charak (2008) found sex difference in preschool latent executive control favoring girls, with indicator measures including putative measures of both inhibition and working memory, although in a follow-up study with a different sample composed only of 3-year-olds and a different task battery, sex differences were not evident (Wiebe, Sheffield, Nelson, Clark, Chevalier, & Espy, 2011). Sex differences in response inhibition favoring women are apparent in adulthood, both behaviorally and in patterns of neural activation (Li, Zhang, Duann, Yan, Sinha, & Mazure, 2009; Yuan, He, Qinglin, Chen, & Li, 2008). Thus, it is reasonable to predict that the course of response inhibition development may reach a higher level or proceed more quickly in girls than in boys.

Response inhibition is closely tied to the construct of self-regulation and related temperamental traits, both conceptually and empirically. Preschool response inhibition is correlated with temperament dimensions including approach or anticipation, inhibitory control, and attention focusing (Wolfe & Bell, 2006). Furthermore early temperament predicts later ability to inhibit prepotent responses. Aksan and Kochanska (2004) found that infants with more fearful temperaments went on to develop better response inhibition skills in the preschool years, suggesting that certain temperament traits may facilitate (or hinder) the later emergence of response inhibition. Similarly, better preschool self-regulation has been linked to better response inhibition in adolescence (Eigsti et al., 2006). Children’s ability to regulate behavioral responses is closely tied to more general behavioral tendencies throughout development.

Response inhibition also is related to other cognitive abilities, including working memory, another aspect of executive control (Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter, & Wager, 2000). Correlations between inhibitory and working memory measures are higher in preschool than later in childhood (Tsujimoto et al., 2007), and in fact putative working memory and inhibition measures appear to tap the same underlying construct in preschool (Wiebe et al., 2008, 2011). This relation may reflect the importance of keeping a goal in mind in order to exert inhibitory control of behavior. More generally, there is some evidence that response inhibition and intelligence, or general cognitive abilities, are related and some have argued for substantial overlap between general cognitive ability and executive skills (e.g., Dempster, 1991). Espy, McDiarmid, Cwik, Stalets, Hamby, and Senn (2004) found that preschool general cognitive ability was correlated with an inhibition composite score, although others have found no such relation later in childhood (Welsh, Pennington, & Groisser, 1991). It is reasonable to expect that the development of response inhibition is related to growth in other cognitive domains.

Finally, variation in children’s family environments, most notably socioeconomic status (SES), has been shown to predict individual differences in response inhibition, and executive control more broadly (Noble, McCandliss, & Farah, 2007; Noble, Norman, & Farah, 2005). Although a relatively new area of study, other studies have also found associations between SES and related constructs such as executive attention (Mezzacappa, 2004) and latent executive control (Hughes, Ensor, Wilson, & Graham, 2010; Wiebe et al., 2011). Although underlying mechanisms are as of yet poorly understood, these relations may be mediated by one or more proximal factors that covary with SES, such as parental disciplinary practices, enrichment of home environment, or exposure to linguistic complexity (Huston, 1999). It is clear that SES is an important variable to consider in elucidating the development of response inhibition.

The Go/no-go Task

A well-studied and sensitive task is critical in order to elucidate the development of response inhibition across the preschool years. The go/no-go task has been used to measure response inhibition across the lifespan (e.g., Rush, Barch, & Braver, 2006; Simpson & Riggs, 2006). In this paradigm, the participant is asked to respond to one stimulus or class of stimuli (i.e., the ‘go’ stimulus), typically presented on most trials to promote a prepotent tendency to respond. On some trials, the ‘no-go’ stimulus is presented, where the participant is instructed not to respond; successful non-response is considered to require inhibition of a prepotent response.

An advantage of this task is that its neural bases are well-mapped and support its validity as a measure of response inhibition. In neuroimaging studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in adults, response inhibition on no-go trials activates a network of brain areas including anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, pre-supplementary motor area, and inferior parietal lobule (Garavan, Ross, Murphy, Roche, & Stein, 2002; Mostofsky et al., 2003; Rubia et al., 2001), with some variation in regions of activation depending on the particular task variant used. A similar network of brain regions is activated by the stop signal task (Logan & Cowan, 1984), another commonly used response inhibition measure (Rubia et al., 2001). In developmental neuroimaging studies, the same network are activated in children and adolescents, although the degree or extent of activation is typically greater in children than adults (e.g., Booth et al., 2003; Durston et al., 2002; Tamm, Menon, & Reiss, 2002), likely reflecting less efficient processing in immature brain regions.

Many studies of preschool response inhibition have used non-computerized versions designed to follow the same logic as computerized tasks, for example, in “Simon Says”-like games (e.g., Aksan & Kochanska, 2004; Carlson, 2005) and search paradigms (Livesey & Morgan, 1991). Computerized go/no-go tasks have been used successfully with preschool children as young as 3 years (Dowsett & Livesey, 2000; Simpson & Riggs, 2006), demonstrating the feasibility of this approach and providing greater comparability of results with the broader literature. Relative to other response inhibition tasks, the go/no-go task requires relatively few trials: Dowsett and Livesey included 20 trials (50% no-go trials), whereas Simpson and Riggs included 24 trials (including either 25% or 75% go trials). The stop signal task—another commonly used response inhibition measure where sequential presentation of ‘go’ and ‘stop’ signals at different relative intervals used to determine length of time required to stop a programmed response—requires many more trials, where one successful adaptation of stop signal task for preschool children included 216 trials (Carver et al., 2001). As such, the go/no-go task seems well-suited to measure individual differences in preschool children, whose short attention spans make it difficult to administer longer tasks, particularly when in the context of more extensive task batteries. Stroop-like tasks also have been used to measure response inhibition, and are correlated with go/no-go performance (Simpson & Riggs, 2006). Stroop-like tasks are less ‘pure’ measures, as children must inhibit the correct response while controlling their attention to different stimulus dimensions to generate the correct response.

A number of task parameters have a demonstrated effect on response inhibition demands. Increasing the frequency of go trials increases the likelihood of errors of commission on no-go trials in early childhood (Simpson & Riggs, 2006), middle childhood, and adulthood (Ciesielski et al., 2004). Inhibitory demands appear to vary dynamically within a run of the task depending on the preceding trial context, in that a longer “run” of go trials results in more errors of commission in middle childhood and adulthood, as well as increased activation of the network of brain regions underlying response inhibition in adults only (Durston et al., 2002). For young children, the rate of stimulus presentation also affects inhibitory demands. Simpson and Riggs (2006) found that when children were given only 1 second to respond, poor task engagement resulted in high no-go performance for some children, as they responded to very few no-go and go stimuli. As such, no-go accuracy was not correlated with Day-Night Stroop performance. When children were given 3 seconds to respond, errors of commission were correlated strongly with Stroop performance, but children performed at or near ceiling on both go and no-go trials, suggesting weaker inhibitory demands. An intermediate condition, where children had 2 seconds to respond, appeared to provide an ideal balance for young preschoolers, as children had more difficulty on no-go than go trials, and no-go accuracy was correlated with Stroop performance.

The Present Study

The overarching goal was to elucidate the developmental trajectory of response inhibition in the preschool period. As part of a larger longitudinal study, children were assessed at four time-points from the ages of 3 through 5 years, using a lagged cohort-sequential design, where groups of children are enrolled at the later assessment ages to directly examine practice effects and disentangle them from developmental change. Concerns about practice effects may be particularly important for executive tasks, as when a task is familiar it is more likely to tap automatic rather than controlled processing, and does not call on executive or frontal processes to the same degree (Shallice & Burgess, 1991).

A preschool-appropriate go/no-go task was selected to measure response inhibition, with task design guided by the extant preschool literature. One key consideration was the pacing of trials. In order to compare performance across all time-points using growth curve modeling, task parameters needed to be identical throughout the study. However, because the study design included assessments of 4- and 5-year-olds, the preferred 2-second trial duration identified in Simpson and Riggs’ (2006) study of 3-year-olds was considered to provide insufficient time pressure to engage response inhibition in older children, but a 1-second trial duration clearly was too fast for the youngest assessment. Based on these considerations and validated by pilot testing, a 1500-millisecond trial duration was selected as suitable for all ages. Another consideration was the rule children needed to learn to distinguish go and no-go trials. Because the study’s focus was response inhibition, it was deemed important to minimize working memory demands by using transparent task rules based on familiar concepts. The task was framed as a fishing game, where children instructed to “catch the fish, but not the sharks.” Go and no-go stimuli (fish and sharks respectively) were selected to share many features, but were nevertheless easily differentiated and familiar to preschool children, in order to facilitate their learning the task rule. To increase the strength of the prepotent response, 75% of trials were go trials, with 40 trials presented in total, to allow for a broader range of variability in performance than in Simpson and Riggs (2006) or Dowsett and Livesey (2000). To permit exploration of inhibitory load induced by preceding trial context, no-go trials followed either 2 or 4 go trials.

Growth curve modeling was used to characterize developmental trajectories of response inhibition between 3 and 5 years (Singer & Willett, 2003). Broader information on child and family characteristics was incorporated into analyses to determine predictors of individual differences in growth. Based on previous research, key variables were sex, socioeconomic status, child temperament, general cognitive ability and working memory task performance.

Method

Participants

The sample included 376 preschool children (191 girls and 185 boys). Participants were recruited through birth announcements, local preschools, the local health department, and by word of mouth, from two Midwestern study sites, a small city and a rural tri-county area. Children were enrolled using a lagged sequential design (Schaie, 1965), with groups of children enrolled at multiple ages and followed to age 5.25 years, to evaluate practice effects that otherwise would be confounded with developmental change in a single cohort longitudinal design. The sample included 219 children who were enrolled at age 3.0 years, 57 at age 3.75, 53 at age 4.5, and 47 at age 5.25. Before enrollment in the study, parents completed a telephone screening, and children with diagnosed developmental or language delays or behavioral disorders, whose primary language spoken in the home was not English, or whose families planned to move out of the area within the study timeline, were not considered further for potential recruitment. Sampling was stratified by sex and sociodemographic risk, where children considered to be at-risk (defined by eligibility for public medical assistance) were oversampled (42% of the sample). Children who obtained standard scores of 70 or below on the Woodcock-Johnson III BIA (n =9), or parental rating t-scores of 70 or higher on the CBCL Externalizing Problems scale (n = 6), or who were diagnosed with developmental or language disorders during longitudinal follow-up (n = 12) were excluded from the present analyses. Three additional children could not be included because they were missing go/no-go data at all time points.

Children’s age at the 3-year assessment ranged from 2.92 to 3.00 years, with a mean of 2 years 11 months 22 days (SD = 13 days), at the 3.75-year assessment ranged from 3.67 to 3.83 years, with a mean of 3 years 8 months 16 days (SD = 16 days), at the 4.5-year assessment ranged from 4.42 to 4.50 years, with a mean of 4 years 5 months 13 days (SD = 15 days), and at the 5.25-year assessment ranged from 5.08 to 5.25 years, with a mean of 5 years 2 months 11 days (SD = 15 days). The sample included 283 non-Hispanic White, 18African American, 1 Asian American, 28 Hispanic, and 46 multi-racial children.

Because of the lagged sequential design, children recruited at later ages had missing data by design at all ages prior to their enrollment. From the 376 children, there were 79 missing observations. Data were missing due to equipment failure (1 observation), examiner error (1 observation), because they refused to complete the go/no-go task or pressed the button for fewer than 10% of both go and no-go stimuli (21 observations), pressed the button to over 90% of both go and no-go stimuli indicating that they did not learn or attend to the rule (13 observations), did not schedule the assessment because they were sick or too busy (15 observations), moved away (10 observations), dropped out of the study (4 observations), or could not be contacted by study staff (12 observations). Additionally, one child died during the course of the study (2 observations missing).

Procedures

Each child was tested individually in a child-friendly laboratory setting, by a trained research technician. The Fish-Shark go/no-go task and Nebraska Barnyard working memory task (described below) were administered as part of a battery of preschool executive control tasks, conducted in a fixed order to ensure that any potential carry-over effects were comparable among children. During the executive control battery, parents completed a packet of questionnaires and an interview about the child’s health, and family background, including maternal education, used as an indicator of SES. Adherence to experimental protocols was maintained by regular team meetings and session reviews with the first author. Children received a small toy and parents received a gift card as compensation for their time and travel expenses. Participants who completed all assessments received an additional gift card as a bonus.

Inhibitory Control Assessment

The Fish-Shark go/no-go task was administered on an IBM-compatible computer using E-Prime 1.2 (Psychological Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). Children used one button on an RB-530 button box (Cedrus Corporation, San Pedro, CA) to respond. Before beginning the task, children were instructed to press the button when they saw a fish, to catch it in their fishing net, but that they should not press the button when they saw a shark, because sharks would break through their net. In an initial training phase, children were presented with all fish and shark stimuli, and practiced pressing the button to catch fish and withholding the button press to avoid catching sharks. Finally, 40 test trials were administered (75% fish trials, 25% shark trials). On each trial, the stimulus (fish or shark) appeared on the screen for 1500 milliseconds or until the child pressed the button. On fish trials when the child correctly pressed the button, a picture of the fish caught in a net appeared on the screen for 1000 milliseconds, accompanied by a bubbling sound, indicating that the child “caught the fish.” On shark trials when the child erroneously pressed the button, a picture of the shark breaking through a net appeared, accompanied by the sound of a buzzer. No feedback was presented when the child did not press the button. There was a 1000 millisecond inter-stimulus interval between end of the previous trial stimulus or feedback and the onset of the next trial stimulus. Trials were block-randomized so that each block of eight trials included six fish trials and two shark trials (where one shark trial followed two fish, and the other shark trial followed four fish, in a manipulation of preceding trial context), and all exemplars (10 fish, three sharks) appeared with roughly equivalent frequency. Trials with responses faster than 200 milliseconds were eliminated from the analysis, as they were too quick to reflect responding to the current stimulus. Proportion correct was computed separately for go and no-go trials, and mean response times (RTs) were calculated for correct go trials. The proportion of hits (correct go trials) and false alarms (incorrect no-go trials) were used to calculate sensitivity (d′; the standardized difference between the hit rate and the false alarm rate, calculated by subtracting the z-score value of the hit rate right-tail p-value from the z-score value of the false alarm rate right-tail p-value; Macmillan & Creelman, 2005). The d′ sensitivity index is used routinely in the signal detection literature and reflects the degree to which a subject responds differentially to two classes of stimuli, where higher values reflect better discrimination.

Working Memory Assessment

The Nebraska Barnyard task (Wiebe et al., 2011; adapted from the Noisy Book task; Hughes et al., 1998) is a computerized working memory span task requiring children to remember a sequence of animal names and press corresponding buttons on a touch screen in the correct order. After an initial practice phase where children respond to the individual animal names, the sequence length is increased incrementally. Testing is discontinued after the child responds incorrectly to all three items for a sequence length. The dependent variable selected for analysis was a summary score. This score was calculated by first calculating the proportion of correct button presses for each span length by dividing correct presses by the total number of presses (e.g., if a child successfully recalled 2 two-item sequences and made one error on the third two-item sequence, the corresponding score would be 5/6 or .83), and then summing these “proportion correct” scores across all administered span lengths (e.g., if a child scored perfectly on one-item sequences, attained a score of .83 on two-item sequences, and did not press any buttons correctly on three-item sequences, the summary score would be 1.83). So that task performance for as many children as possible could be included at all time points, children who did not recall even a single animal on the practice trials (e.g., because of failure to understand the task or non-compliance) were assigned a score of 0 for the task for that timepoint (5 observations). Children with missing data due to audiovisual malfunction were assigned their memory span score (calculated online by the examiner; 3 observations), because the summary and span scores were highly correlated (r > .90), but the summary scores had a greater range of possible values.

Temperament ratings

At each assessment, the child’s parent (usually the mother) completed the very short form of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ-VS; Putnam & Rothbart, 2006). The CBQ Surgency, Effortful Control, and Negative Affect scales were used for these analyses. Scale reliability scores for this sample ranged from .71 and .74 (CBQ Surgency α = .74; CBQ Effortful Control α = .71; CBQ Negative Affect α = .71).

General cognitive ability

Children completed the Woodcock-Johnson Brief Intellectual Ability Assessment (BIA; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) at enrollment and study completion. This standardized test includes three subscales—vocabulary, concept formation, and visual matching—providing a broad assessment of cognitive ability. BIA standard scores from age 5.25 were selected as reflecting a more stable estimate of a child’s IQ. For those children who did not complete the BIA at study completion because of time constraints, noncompliance, or attrition, BIA at intake was substituted (n = 36).

Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Mean levels of performance and correlations among performance indicators were examined at each age. Growth curve modeling analyses were conducted using Proc Mixed to examine patterns of change across the preschool period, and predictors of individual variation in children’s level of performance and growth patterns, following procedures described by Singer and Willett (2003).

First, plots of individual and mean growth curves were examined. Next, the best fitting baseline growth model for each outcome was determined through a series of nested model comparisons, testing whether the fixed and random effects for growth parameters (intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope) differed significantly from 0. Time was coded so that the intercept reflected initial status (i.e., performance at age 3 years). After the best fitting growth model was determined, time-invariant covariates (sex, maternal education, and IQ) and cohort effects (dummy-coded, where each of the lagged cohorts were represented by a separate dummy variable) were entered as a block, and then trimmed using a backward selection criterion. Finally, time-varying covariates (working memory and maternal temperament ratings) were evaluated. Maternal education was centered at 12 years, IQ was centered at 100, and time-varying covariates were centered at the means of the 3-year timepoint to ease interpretation of growth parameters. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to permit statistical tests of both fixed and random effects (Singer & Willett, 2003); therefore, −2 log likelihood deviance difference tests were examined to determine retention of effects in nested models, and p-values were examined to determine retention of covariates, with a critical α of .05. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was examined as an index of relative model fit, where lower values indicate better fit.

Results

Initially, analyses were conducted examining the effect of preceding trial context (dividing no-go accuracy into two categories, no-go trials preceded by two go trials and no-go trials preceded by four go trials). No-go trial performance did not vary significantly as a function of preceding trial context at any age, and correlations between the two no-go variables and covariates were similar in magnitude and statistical significance. Thus, we collapsed across preceding trial context and the presented results are based on overall no-go performance.

Descriptive statistics for go/no-go task performance at each age are given in Table 1, and sample demographic characteristics and other potential covariates are summarized in Table 2. All measures of accuracy increased monotonically across the preschool period, whereas reaction time increased between 3.0 and 3.75 years, reflecting slower responding, then decreased across the remaining assessments, reflecting quicker responding. At the 4.5-year and 5.25-year assessments, some children attained ceiling levels of performance on go and no-go trial accuracy, resulting in higher skewness and kurtosis than are preferred (see Table 1). However, distributions of d′ scores and response times better approximated a normal distribution at all time-points, suggesting that these indices of performance were better suited for growth curve analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Go/No-Go Performance Indices.

| Dependent Measure | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age = 3 years (n = 196)

| |||||

| Go proportion correct | .62 | .212 | 0–1 | −0.92 | 0.48 |

| Go RT (milliseconds; n = 194) | 873 | 150.4 | 407–1294 | 0.13 | 0.29 |

| No-go proportion correct | .47 | .321 | 0–1 | 0.19 | −1.35 |

| Sensitivity (d′) | 0.27 | 0.845 | −1.73–2.39 | 0.45 | −0.23 |

|

| |||||

| Age = 3 years 9 months (n = 260)

| |||||

| Go proportion correct | .75 | .185 | .07–1.0 | −1.03 | 0.76 |

| Go RT (milliseconds) | 934 | 155.5 | 378–1300 | 0.03 | −0.29 |

| No-go proportion correct | .74 | .312 | 0–1 | −1.16 | 0.02 |

| Sensitivity (d′) | 1.54 | 1.114 | −1.27–3.77 | −0.44 | −0.45 |

|

| |||||

| Age = 4 years 6 months (n = 311)

| |||||

| Go proportion correct | .89 | .131 | .11–1 | −2.24 | 6.64 |

| Go RT (milliseconds) | 835 | 150.0 | 538–1292 | 0.41 | −0.36 |

| No-go proportion correct | .84 | .206 | 0–1 | −2.08 | 4.44 |

| Sensitivity (d′) | 2.53 | 0.889 | −0.62–3.77 | −1.10 | 1.42 |

|

| |||||

| Age = 5 years 3 months (n = 355) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Go proportion correct | .96 | .072 | 0.27–1.0 | −4.19 | 28.27 |

| Go RT (milliseconds) | 733 | 137.1 | 427–1280 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| No-go proportion correct | .89 | .137 | .10–1.0 | −2.03 | 5.87 |

| Sensitivity (d′) | 3.08 | 0.614 | 0.22–3.77 | −1.06 | 1.51 |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Covariates.

| Dependent Measure | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 376 | 49.2% boys | -- | -- |

| Maternal education (years) | 376 | 14.78 | 1.88 | 11–18 |

| General cognitive ability | 376 | 103 | 12.1 | 71–147 |

| CBQ Surgency | ||||

| Age 3 years | 196 | 4.63 | 0.718 | 1.92–6.42 |

| Age 3 years 9 months | 260 | 4.59 | 0.819 | 1.67–6.67 |

| Age 4 years 6 months | 311 | 4.68 | 0.798 | 2.33–6.83 |

| Age 5 years 3 months | 355 | 4.72 | 0.787 | 1.75–6.67 |

| CBQ Effortful Control | ||||

| Age 3 years | 196 | 5.32 | 0.650 | 3.38–6.92 |

| Age 3 years 9 months | 260 | 5.49 | 0.646 | 3.45–6.83 |

| Age 4 years 6 months | 311 | 5.56 | 0.625 | 3.67–6.92 |

| Age 5 years 3 months | 355 | 5.61 | 0.657 | 2.92–7.00 |

| CBQ Negative Affect | ||||

| Age 3 years | 196 | 3.84 | 0.760 | 1.67–5.75 |

| Age 3 years 9 months | 260 | 4.05 | 0.776 | 2.00–6.08 |

| Age 4 years 6 months | 311 | 4.05 | 0.790 | 1.83–6.42 |

| Age 5 years 3 months | 355 | 4.01 | 0.800 | 1.83–6.17 |

| Working Memory score | ||||

| Age 3 years | 196 | 1.11 | 0.578 | 0.00–3.06 |

| Age 3 years 9 months | 260 | 1.91 | 0.740 | 0.33–3.89 |

| Age 4 years 6 months | 311 | 2.70 | 0.957 | 0.00–5.16 |

| Age 5 years 3 months | 355 | 3.48 | 0.872 | 1.00–5.94 |

Correlations among go/no-go performance indices are shown in Table 3. Faster responding was related to more accurate performance on go trials at all time-points. This correlation was moderate in magnitude at age 3 years, and stronger at later ages. In contrast, faster responding was related to poorer performance on no-go trials, and this correlation was stronger at earlier ages. At age 3, there was a strong negative correlation between accuracy on go trials and no-go trials, but correlation did not differ from zero at the later three ages. Taken together, these findings suggest a tradeoff in young preschool children, where children who responded more quickly and accurately on go trials had greater difficulty inhibiting responding on no-go trials, but that this tradeoff was attenuated as children grew older. Consistent with this suggestion, at age 3, children who responded more slowly were better at discriminating go and no-go stimuli, as indexed by d′, but at age 3.75 there was no relation between mean RT and d′. At 4.5 and 5.25 years, faster responding was associated with better discrimination. As well, d′ was strongly correlated with no-go accuracy at all time-points, whereas a significant correlation between d′ and go accuracy was observed only from 3.75 years onward. Correlations among potential covariates, and between covariates and go/no-go performance, are shown in Table 4. Most correlations involving general cognitive ability and working memory, and response inhibition were significant, whereas only half of correlations involving sex differed from zero. Maternal education and temperament showed less consistent patterns of association.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Go/No-Go Performance Indices at Each Timepoint.

| Go/No-go Performance Indices | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Go RT | No-go Accuracy | Sensitivity (d′) | |

| Age = 3 years (n= 196)

| |||

| Go Accuracy | −.28*** | −.56*** | .12+ |

| Go RT (n = 194) | .46*** | .32*** | |

| No-go Accuracy | .75*** | ||

|

| |||

| Age = 3 years 9 months (n = 260)

| |||

| Go Accuracy | −.42*** | −.18* | .40*** |

| Go RT | .43*** | .13* | |

| No-go Accuracy | .82*** | ||

|

| |||

| Age = 4 years 6 months (n = 311)

| |||

| Go Accuracy | −.63*** | −.06 | .60*** |

| Go RT | .28*** | −.24*** | |

| No-go Accuracy | .74*** | ||

|

| |||

| Age = 5 years 3 months (n = 355)

| |||

| Go Accuracy | −.55*** | −.08 | .59*** |

| Go RT | .27*** | −.16** | |

| No-go Accuracy | .73*** | ||

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .10

Table 4.

Correlations Between Go/No-Go Performance Indices and Covariates.

| Go/No-go Performance | Time-invariant Covariates | Time-varying Covariates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Maternal Education | IQ | Surgency | Effortful Control | Negative Affect | Working Memory | |

| Age = 3 years (n= 196)

| |||||||

| Go Accuracy | .23** | .06 | .05 | .20** | −.11 | −.09 | −.02 |

| Go RT (n = 194) | −.04 | .11 | .21** | −.14+ | .07 | .06 | .32*** |

| No-go | −.25*** | .01 | .16* | −.17* | .20** | .11 | .16* |

| Accuracy Sensitivity | −.11 | .05 | .23** | −.04 | .16* | .03 | .17* |

|

| |||||||

| Age = 3 years 9 months (n = 260)

| |||||||

| Go Accuracy | .11+ | .05 | .22*** | .13* | .00 | −.10 | .13* |

| Go RT | −.11+ | .16* | .05 | −.04 | .05 | .10 | .04 |

| No-go | −.15* | .18** | .26*** | −.02 | .02 | −.07 | .19** |

| Accuracy Sensitivity | −.09 | .21*** | .37*** | .05 | .01 | −.12* | .27*** |

|

| |||||||

| Age = 4 years 6 months (n = 311)

| |||||||

| Go Accuracy | .16** | .00 | .17** | .03 | −.07 | −.06 | .12* |

| Go RT | −.15** | .04 | −.14* | −.11* | .07 | .05 | −.17** |

| No-go | −.14* | .10+ | .27*** | .06 | .14* | −.05 | .21*** |

| Accuracy Sensitivity | −.01 | .09 | .36*** | −.03 | .07 | −.09 | .27*** |

|

| |||||||

| Age = 5 years 3 months (n = 355)

| |||||||

| Go Accuracy | .10+ | .16** | .26*** | .05 | −.12* | .00 | .24*** |

| Go RT | −.13* | −.02 | −.29*** | −.09+ | .09+ | .04 | −.25*** |

| No-go | −.15** | .05 | .19*** | −.10+ | .14** | −.04 | .11* |

| Accuracy Sensitivity | −.04 | .16** | .35*** | −.04 | .02 | −.05 | .27*** |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p<.05;

p < .10

Growth curve analyses were conducted separately for d′ and go trial RTs. Table 5 summarizes the results of the unconditional growth models. For speed of responding on go trials, the best-fitting unconditional growth model included both linear and quadratic slopes, to capture the inverted U-shape apparent in the observed means (−2LL = 14289, AIC = 14303). There was significant variability among children in intercept and linear slope, modeled as random effects, but not in quadratic slope, modeled as a fixed effect. Intercept and linear slope were correlated (r = −.50, p < .001), where children who responded more slowly at age 3.0 showed more gradual linear change in response speed over the preschool period.

Table 5.

Results of the Unconditional Growth Models

| γ | SE | Estimated Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Go RT | |||

| Intercept | 882.2*** | 10.67 | 10131*** |

| Linear slope | 60.0*** | 12.77 | 2154*** |

| Quadratic slope | −37.1*** | 3.73 | - - - |

| Residual | 13979*** | ||

|

| |||

| Sensitivity (d′) | |||

| Intercept | 0.24*** | 0.058 | 0.234*** |

| Linear slope | 1.49*** | 0.073 | - - - |

| Quadratic slope | −0.18*** | .022 | - - - |

| Residual | 0.513*** | ||

Note. The intercept parameter represents values at age 3.0 years (initial assessment). The linear slope parameter represents the slope of the line tangent to the growth trajectory at age 3.0 years.

p < .001

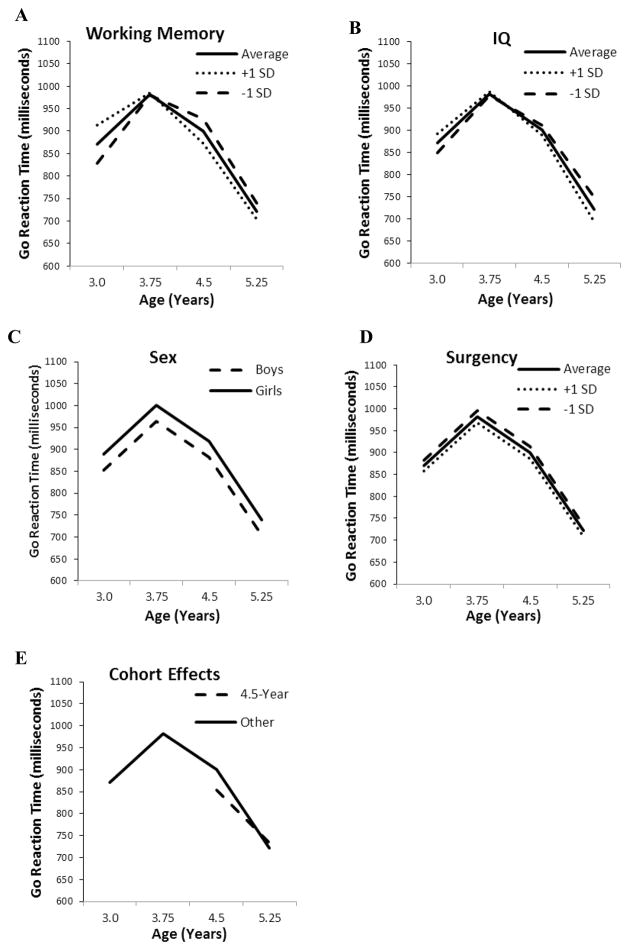

The final, conditional growth model for go trial RT is summarized in the left column of Table 6 (−2LL = 14181, AIC = 14213, ΔAIC = 76). Calculation of pseudo-R2 statistics (Singer & Willett, 2003) revealed that, together, the covariates accounted for 7.1% of the variability in intercepts, 30.6% of the variability in slopes, and 7.1% of the residual variability. Working memory (a time-varying predictor) was related to both intercept and linear slope, and interacted with quadratic change parameters. As illustrated in Figure 1, Panel A, children with better working memory performance responded more slowly at age 3.0, and evidenced a greater increase in their speed of responding, so that by age 5.25 better working memory was associated with quicker responding. There was a similar crossover effect for general cognitive ability, which predicted both intercept and slope (see Figure 1, Panel B). There were sex differences in intercept only, where boys responded more quickly than girls (see Figure 1, Panel C). Likewise, higher parent-rated surgency (also a time-varying predictor) was related to quicker responding (see Figure 1, Panel D), although negative affect and effortful control were unrelated to response speed. Generally, there were no differences among the cohorts in their growth parameters, with the exception of children in the 4.5-year cohort, who differed from other children in intercept and slope. Children in the 4.5-year cohort responded more quickly initially, with a compensatory decrease in linear slope, resulting in convergence with the other cohorts at age 5.25 years (see Figure 1, Panel E). Maternal education was unrelated to response speed growth parameters.

Table 6.

Results of the Conditional Growth Models

| Go RT | Sensitivity (d′) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| γ | SE | Estimated Variance | γ | SE | Estimated Variance | |

| Effects on intercept parameter | ||||||

| Intercept | 888.5*** | 11.72 | 9415*** | 0.211*** | 0.056 | 0.147*** |

| IQ | 1.8* | 0.85 | 0.017*** | 0.005 | ||

| Sex | −36.1*** | 10.61 | - - - | - - - | ||

| Working memory | 74.5*** | 16.65 | 0.096** | 0.035 | ||

| Surgency | −17.0** | 6.14 | - - - | - - - | ||

| Age 4.5 cohort | −160.5** | 62.00 | - - - | - - - | ||

|

| ||||||

| Effects on linear slope parameter | ||||||

| Linear slope | 90.5*** | 18.62 | 1494*** | 1.36*** | 0.078 | - - - |

| IQ | −1.4*** | 0.39 | 0.016* | 0.006 | ||

| Working memory | −90.3*** | 15.68 | - - - | - - - | ||

| Age 4.5 cohort | 57.3* | 24.37 | - - - | - - - | ||

|

| ||||||

| Effects on quadratic slope parameter | ||||||

| Quadratic slope | −39.2*** | 6.95 | - - - | −0.16*** | 0.022 | - - - |

| IQ | - - - | - - - | −0.006** | 0.0018 | ||

| Working memory | 19.5*** | 4.05 | - - - | - - - | ||

| Residual | 12992*** | 0.507*** | ||||

Note. All growth parameters are centered at age 3.0 years. Estimated IQ was centered at 100, cohort was dummy-coded (4.5-year cohort=1; other=0), sex was dummy-coded (girls=0; boys=1), and working memory were centered at their respective 3.0-year means.

p < .001;

p < .01;

p ≤ .05

Figure 1.

Effects of sex, general cognitive ability, working memory, surgency, and cohort on predicted developmental trajectories for response times. All predicted trajectories are calculated taking into account mean age-related changes in time-varying covariates.

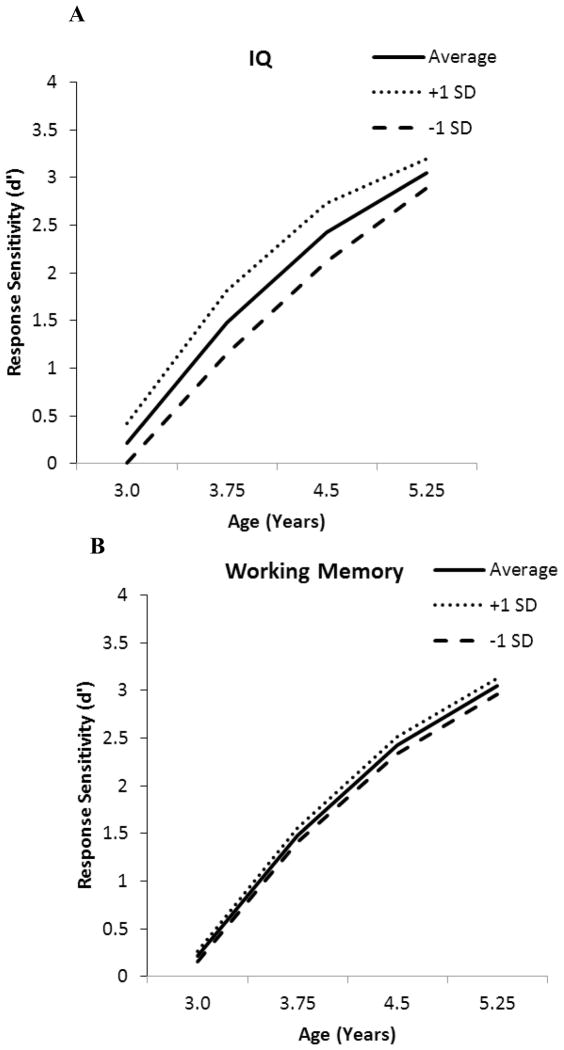

To characterize developmental change in accuracy, the same analytic approach was applied to the d′ sensitivity scores. For d′, the best-fitting growth curve also included linear and quadratic growth terms, indicating that children more accurately differentiated go and no-go stimuli with development, but growth decelerated over time (−2LL = 2745, AIC = 2755). Children varied in estimated initial status, modeled as a random effect, but children did not differ individually in estimated linear or quadratic growth, modeled as fixed effects. Among the covariates considered for inclusion in the model, the significant predictors were general cognitive ability and working memory (see Table 6, right column; −2LL = 2647, AIC = 2665, ΔAIC = 90). Together, these predictors accounted for 37.2% of the variability in intercept, and 1.2% of the residual variability. General cognitive ability was a significant predictor of intercept, and interacted with both the linear and quadratic slope terms, so that the overall influence of IQ on children’s go/no-go response sensitivity increased, then decreased, across the preschool period (see Figure 2, Panel A). Working memory, a time-varying predictor, was a significant predictor of intercept, and interacted with linear slope only. Children with better working memory skills were more accurate in their discrimination of go and no-go stimuli, and the influence of working memory increased with age (see Figure 2, Panel B). Temperament, maternal education, and cohort were unrelated to the growth parameters for d′.

Figure 2.

Effects of general cognitive ability and working memory on predicted developmental trajectory for sensitivity (d′). All predicted trajectories are calculated taking into account mean age-related changes in time-varying covariates.

To further examine children’s accuracy, considering performance on go relative to no-go trials, proportion correct scores were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), which is more robust to violation of normality assumptions, particularly with large sample sizes and similar variances (Boneau, 1960). ANOVAs were conducted using SAS’s Proc GLM, separately for each age, because the number of children differed substantially across assessments because of the lagged sequential design. At age 3.0 years, a 2 (sex: girl, boy) × 2 (trial type: go, no-go) ANOVA with repeated measures on trial type was computed. At later ages, cohort was also included as a between-subject factor. ANOVAs are summarized in Table 7; to facilitate comparisons across studies using within- and between-subjects designs, effect sizes are reported using the generalized eta-squared (η2G) measure, as recommended by Bakeman (2005).

Table 7.

Analysis of Variance for Accuracy on Go and No-Go trials, by age.

| 3.0 years (n = 196) | 3.75 years (n = 260) | 4.5 years (n = 311) | 5.25 years (n = 355) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| df | F | η2G | df | F | η2G | df | F | η2G | df | F | η2G | |

| Between subjects

| ||||||||||||

| Sex | 1 | 2.46 | .003 | 1 | 0.73 | .001 | 1 | 0.24 | .0004 | 1 | 2.55 | .003 |

| Cohort | - | -- | -- | 1 | 2.06 | .003 | 1 | 2.87 | .009 | 1 | 1.57 | .006 |

| Sex × Cohort | - | -- | -- | 1 | 0.17 | .0003 | 1 | 1.12 | .004 | 1 | 2.22 | .009 |

| Error | 194 | (0.035) | 256 | (0.009) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Within subjects

| ||||||||||||

| Trial type | 1 | 23.23** | .089 | 1 | 4.73* | .010 | 1 | 16.01** | .027 | 1 | 48.39** | .074 |

| Sex × Trial type | 1 | 15.10** | .058 | 1 | 2.69 | .006 | 1 | 12.08** | .020 | 1 | 12.18** | .019 |

| Cohort × Trial type | - | -- | -- | 1 | 9.62** | .021 | 2 | 3.62* | .012 | 3 | 1.02 | .005 |

| Sex × Cohort × Trial type | - | -- | -- | 1 | 1.53 | .003 | 2 | 0.62 | .002 | 3 | 0.79 | .004 |

| Error | 194 | (0.105) | 256 | (0.072) | 305 | (0.030) | 347 | (0.013) | ||||

Note: values enclosed in parentheses represent mean square errors. η2G = generalized effect size.

p < .01;

p < .05

At all ages, children were more accurate on go trials than no-go trials (for means, see Table 1). At all ages except 3.75 years, the main effect of trial type was qualified by an interaction with sex. Follow-up ANOVAs revealed that at each age, boys outperformed girls on go trials (at age 3.0, Mboy = 67%, SD = .160; Mgirl = 58%, SD = 24.2; at age 4.5, Mboy = 91%, SD = 9.8; Mgirl = 87%, SD = 15.3; at age 5.25, Mboy = 97%, SD = 6.3, Mgirl = 95%, SD = 8.0), but were less accurate than girls on no-go trials (at age 3.0, Mboy = 39%, SD = 30.9; Mgirl = 55%, SD = 31.5; at age 4.25, Mboy = 81%, SD = 23.0; Mgirl = 87.3, SD = 17.6; at age 5.25, Mboy = 87%, SD = 15.0, Mgirl = 91%, SD = 12.0). At the 3.75-year and 4.5-year assessments, cohort interacted with trial type. There were no cohort effects on go trial performance, but on no-go trials, children completing the task for the first time performed less accurately than children with previous experience (at age 3.75, M3.0 = 77%, SD = 29.6; M3.75 = 64%, SD = 35.0; at age 4.25, M4.5 = 77%, SD = 24.3; M3.75 = 86%, SD = 19.1; M3.0 = 86%, SD = 19.6). Notably, there were no significant main effects of sex or cohort.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to delineate the growth of response inhibition in the preschool years and to identify factors that contributed to individual differences in change over time. Children completed the go/no-go task, a commonly-used and validated measure, at multiple time points representing the preschool period. From ages 3 through 5.25 years, there were marked improvements in both accuracy and speed, but the trajectories were quite different, and showed distinct patterns of relations with predictors. Children generally had more difficulty with no-go trials than go trials, suggesting that the attempt to induce a prepotent tendency to respond was successful. For accuracy, as indexed by d′, which reflects children’s differential responding to go and no-go stimuli, growth was primarily linear, with a relatively small nonlinear component reflecting decelerating improvement in accuracy later in the preschool years; relations with predictors were straightforward, where better working memory and IQ predicted more accurate responding. The trajectory for response speed, in contrast, was primarily curvilinear, reflecting a slowing of children’s responding between 3 and 3.75 years of age, following by faster responding over the remaining assessments. Relations with predictors were complex, where male sex and higher surgency predicted faster responding throughout the preschool period, but better working memory and IQ predicted slower responding at younger ages, but faster responding in older preschool children.

In the present study, the same go/no-go task was administered at each age as required for growth curve analyses, but the manner in which children performed that task changed with age, where the most dramatic change was observed between 3 and 3.75 years. At age 3, children responded quickly but showed poor discrimination between the two classes of stimuli, in that the mean intercept of the growth curve for d′ index of accuracy (reflecting predicted initial status) did not differ significantly from 0. By age 3.75, children had improved in accuracy, coupled with slower responding, suggesting that children had become more strategic in deployment of response inhibitory skills. From 3.75 years onward, children showed progressive improvement in both speed and accuracy. Considered together, the mean trajectories for speed and accuracy may reflect both changing speed-accuracy tradeoffs and improvements in inhibitory control. This implies that, although the go/no-go typically is conceptualized as a simple response inhibition task, multiple aspects of children’s performance must be considered to understand how they deploy their abilities to result in a given level of task performance (e.g., a child may do well on no-go trials because of response inhibition or inattention; to differentiate these possibilities, go trial performance must be considered as well).

A key aim of this study was to identify predictors of individual differences in response inhibition growth and test their relative contribution. The strongest and most consistent relations with go/no-go outcomes were observed for cognitive covariates. General cognitive ability was related to both speed and accuracy, consistent with theoretical suggestions and previous empirical findings in preschool children. Working memory independently contributed to both outcome measures, highlighting the importance of keeping information in mind for accurately and efficiently inhibiting a prepotent response (e.g., remembering the rule). This finding converges with the notion of goal neglect as a problem in preschool executive control, where young children have difficulty maintaining a representation of task goals (Towse, Lewis, & Knowles, 2007). Because working memory task performance was modeled as a time-varying covariate in the growth curve models, it accounts for both intra- and interindividual variability, that is, working memory skills are associated with both age-related improvement and individual differences in response inhibition. The close coupling of response inhibition and working memory in this preschool sample is consistent with findings that executive control may be a unitary construct in early childhood (Wiebe et al., 2008, 2011). The relation between response speed and both general cognitive ability and working memory changed with age, where at age 3, better cognitive skills were related to slower responding, whereas at older ages, better cognitive skills were related to faster responding, possibly reflecting age differences in the ability to monitor performance and select the optimal response speed to maximize accuracy.

Girls and boys showed differed patterns of response inhibition development. Analyses of accuracy separated by trial type (go vs. no-go) revealed sex differences at most ages, where girls were more accurate than boys on no-go trials, reflecting better response inhibition, but were less accurate on go trials. Boys responded more quickly on average, which may have contributed to their greater go-trial accuracy and relative difficulty withholding responding on no-go trials. In general, boys have higher levels of activity (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974), which could contribute to greater difficulty in withholding a motor response. There also are sex-related differences in sensitivity to feedback that might have contributed to different response strategies (e.g., emphasis on avoiding errors of omission or commission), as girls have been found to have larger neural responses to negative feedback than boys (Carlson, Zayas, & Guthormsen, 2009). These differences in early childhood could contribute to sex differences in the risk for ADHD, which has been linked to altered reward sensitivity and related neural activation (Stark et al., 2011).

We expected that child temperament would be an important predictor of individual differences in children’s response inhibition development. Effortful control, the self-regulatory component of temperament, has considerable conceptual overlap with response inhibition, and has previously been found to relate to inhibitory task performance in preschoolers (Wolfe & Bell, 2004). In the present study, effortful control was significantly correlated with no-go performance at three of the four time-points, and with d′ and go performance at a single time-point. However, these correlations were small in size, and effortful control did not predict growth or age-related differences in response speed or d′ sensitivity in the growth curve analyses. The relatively weak relations between effortful control and response inhibition indicate that the two constructs do not fully overlap, and may be attributable to differences in the nature of what is regulated: response inhibition prototypically involves regulation of cognitive processes and motor responses, whereas effortful control typically involves the regulation of behavior in the socio-emotional context. Only one dimension of temperament, surgency, emerged as a significant predictor in the growth curve analyses, and was associated only with response speed.

Of note is the absence of relations with response inhibition for some covariates. Maternal education, an index of SES, was correlated with some aspects of go/no-go performance, but in the growth curve analyses, maternal education was no longer a significant predictor. Because the sample was enrolled to represent a broad spectrum of socioeconomic backgrounds, it is unlikely that this null result is due to a restricted range. Rather, other predictors in the model may have a more direct relation with response inhibition. Consistent with this suggestion, in supplementary analyses (available from the first author) when IQ was not included as a predictor, maternal education did predict accuracy, indicating its effect is likely mediated through other more proximal skills or variables.. Finally, unlike several previous studies (e.g., Durston et al., 2002; Eigsti et al., 2006), there was no effect of preceding trial context on no-go accuracy. Children in the present study were younger than those in previous studies, and fewer trials were administered, with only two levels of preceding trial context, in contrast with three levels used in the previous studies, which may have contributed to the null findings.

Several limitations must be kept in mind in considering the findings from this study. First, although we included a wide range of covariates, other unmeasured factors likely also contribute to growth in response inhibition. For example, speed of processing changes rapidly in the preschool years (Kail, 1991), and may contribute to the patterns of growth in reaction times, but was not assessed as a time-varying covariate in the present study. Second, the go/no-go task was selected because it is a commonly-used task with ample evidence for its validity as a measure of response inhibition, but future research should examine other measures of response inhibition (e.g., the stop signal task) to test whether developmental transitions and relations with covariates are similar to those identified in the present study. If the observed findings are indicative of growth in the underlying response inhibition construct, similar patterns would be predicted, whereas cross-task differences would indicate a larger role for task-specific factors.

There was clear evidence for rapid development in response inhibition at age 3, marked by curvilinear change in reaction times coupled with substantial increases in accuracy and changes in relations with cognitive covariates. The finding of a shift between 3 and 3.75 years dovetails with studies identifying transition points at age 3 in other domains including theory of mind (Carlson, Moses, & Breton, 2002) and set-shifting (Zelazo, Frye, & Rapus, 1996). It would be useful to conduct a more fine-grained longitudinal study of 3-year-old children, with closely-spaced sampling throughout the year. More frequent assessments would facilitate detailed characterization of response inhibition growth in this period of rapid transition, and concurrent measurement of predictors would enable better specification of relationships between predictors and response inhibition growth. However, such a study would need to carefully address the effects of repeated exposure on go/no-go performance. In the present study, there were no significant cohort effects for the d′ sensitivity measure providing a summary of accuracy across trial types, but at two (of three) follow-up time-points, children completing the task for the first time performed more poorly on no-go trials relative to children who were repeating the task. In the growth curve analyses, the only significant cohort effect was for the 4.5-year cohort (i.e., all other cohorts’ performance could be modeled using the same growth parameters), and only for response time. These results suggest that response inhibition is easier with previous exposure to a task context, and are consistent with the long-standing finding in the neuropsychological literature that task novelty maximizes executive demands (Shallice & Burgess, 1991).

Finally, future follow-up studies of the present sample will examine how individual differences in preschool growth of response inhibition relate to children’s outcomes later in development. We might expect that the profile of performance associated with risk for later adjustment problems may change over the preschool years, just as the relations between response inhibition and some predictors changed between ages 3 and 5. Furthermore, given that response inhibition was most strongly related to cognitive covariates, skills such as working memory are strong targets for early intervention. This line of research will build on a growing body of literature linking preschool response inhibition, and executive control more broadly, to important outcomes such as academic achievement (e.g., Altemeier et al., 2008; Bull, Espy, Wiebe, Sheffield, & Nelson, in press) and developmental psychopathology (e.g., Berlin et al., 2003; Espy, Sheffield, Wiebe, Clark, & Moehr, 2011).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants MH065668 and DA014661 to Kimberly Andrews Espy, DA024769 to Sandra Wiebe, and DA023653 to Kimberly Andrews Espy and Lauren Wakschlag. Portions of these data were presented at the meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, April 2010, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. We thank the members of the Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory for assistance with data collection and coding.

Contributor Information

Sandra A. Wiebe, University of Alberta

Tiffany D. Sheffield, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Kimberly Andrews Espy, University of Oregon and University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

References

- Aksan N, Kochanska G. Links between systems of inhibition from infancy to preschool years. Child Development. 2004;75:1477–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemeier LE, Abbott RD, Berninger VW. Executive functions for reading and writing in literacy development and dyslexia. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2008;30(5):588–606. doi: 10.1080/13803390701562818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R. Recommended effect size statistics for repeated measures designs. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37(3):379–384. doi: 10.3758/bf03192707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin L, Bohlin G, Rydell AM. Relations between inhibition, executive functioning, and ADHD symptoms: A longitudinal study from age 5 to 8 ½ years. Child Neuropsychology. 2003;9:255–266. doi: 10.1076/chin.9.4.255.23519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boneau AC. The effects of violations of assumptions underlying the t test. Psychological Bulletin. 1960;57(1):49–64. doi: 10.1037/h0041412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JR, Burman DD, Meyer JR, Lei Z, Trommer BL, Davenport ND, et al. Neural development of selective attention and response inhibition. NeuroImage. 2003;20:737–751. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00404-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull R, Espy KA, Wiebe SA, Sheffield TD, Nelson JM. Using confirmatory factor analysis to understand executive control in preschool children: Sources of variation in emergent mathematic achievement. Developmental Science. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01012.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM. Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28(2):595–616. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Moses LJ, Breton C. How specific is the relation between executive function and theory of mind? Contributions of inhibitory control and working memory. Infant and Child Development. 2002;11:73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Wang TS. Inhibitory control and emotion regulation in preschool children. Cognitive Development. 2007;22(4):489–510. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Zayas V, Guthormsen A. Neural correlates of decision making on a gambling task. Child Development. 2009;80(4):1076–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver AC, Livesey DJ, Charles M. Age related changes in inhibitory control as measured by stop signal task performance. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;107(1–2):43–61. doi: 10.3109/00207450109149756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Siegler RS. Across the great divide: Bridging the gap between understanding of toddlers’ and older children’s thinking. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2000;65(2):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski KT, Harris RJ, Cofer LF. Posterior brain ERP patterns related to the go/no-go task in children. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:882–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkum PV, Siegel LS. Is the continuous performance task a valuable research tool for use with children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1993;34(7):1217–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MC, Amso D, Anderson LC, Diamond A. Development of cognitive control and executive functions from 4 to 13 years: Evidence from manipulations of memory, inhibition, and task switching. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2037–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster FN. Inhibitory processes: A neglected dimension of intelligence. Intelligence. 1991;15(2):157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. Developmental time course in human infants and infant monkeys, and the neural bases, of inhibitory control in reaching. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1990;608:637–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb48913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Taylor C. Development of an aspect of executive control: Development of the abilities to remember what I said and to “do as I say, not as I do. Developmental Psychobiology. 1996;29:315–334. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199605)29:4<315::AID-DEV2>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett SM, Livesey DJ. The development of inhibitory control in preschool children: Effects of “executive skills” training. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;36:161–174. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(200003)36:2<161::aid-dev7>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durston S, Thomas KM, Yang Y, Ulug AM, Zimmerman RD, Casey BJ. A neural basis for the development of inhibitory control. Developmental Science. 2002;5:F9–F16. [Google Scholar]

- Eigsti IM, Zayas V, Mischel W, Shoda Y, Ayduk O, Dadlani MB, et al. Predicting cognitive control from preschool to late adolescence and young adulthood. Psychological Science. 2006;17(6):478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy KA, Bull R, Martin J, Stroup W. Measuring the development of executive control with the Shape School. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:373–381. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy KA, McDiarmid MM, Cwik MF, Stalets MM, Hamby A, Senn TE. The contributions of executive functions to emergent mathematics skills in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2004;26:465–486. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2601_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy KA, Sheffield TD, Wiebe SA, Clark CAC, Moehr MJ. Executive control and dimensions of problem behaviors in preschool children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:33–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Ross TJ, Murphy K, Roche RAP, Stein EA. Dissociable executive functions in the dynamic control of behavior: Inhibition, error detection, and correction. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1820–1829. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garon N, Bryson SE, Smith IM. Executive function in preschoolers: A review using an integrative framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(1):31–60. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2(10):861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Ensor R, Wilson A, Graham A. Tracking executive function across the transition to school: A latent variable approach. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35:1, 20–36. doi: 10.1080/87565640903325691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston AC. Effects of poverty on children. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda C, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press; 1999. pp. 391–411. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH. The inhibition of automatic saccades in early infancy. Developmental Psychobiology. 1995;28:281–291. doi: 10.1002/dev.420280504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LB, Rothbart MK, Posner MI. Development of executive attention in preschool children. Developmental Science. 2003;6:498–504. [Google Scholar]

- Kail R. Developmental change in speed of processing during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:490–501. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenberg L, Korkman M, Lahti-Nuuttila P. Differential development of attention and executive functions in 3- to 12-year-old Finnish children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2001;20:407–428. doi: 10.1207/S15326942DN2001_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(2):220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Rich BA, Vinton DT, Nelson EE, Fromm SJ, Berghorst LH, et al. Neural circuitry engaged during unsuccessful motor inhibition in pediatric bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):52–60. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.A52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, Culhane KA, Hargmann J, Evankovich K, Mattson AJ, Harward H, et al. Developmental changes in performance on tests of purported frontal lobe functioning. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1991;7(3):377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Li CSR, Zhang S, Duann JR, Yan P, Sinha R, Mazure CM. Gender differences in cognitive control: An extended investigation of the stop signal task. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2009;3:262–276. doi: 10.1007/s11682-009-9068-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey DJ, Morgan GA. The development of response inhibition in 4- and 5-year-old children. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1991;43:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: a theory of an act of control. Psychological Review. 1984;91(3):295–327. doi: 10.1037/a0035230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Garver KE, Urban TA, Lazar NA, Sweeney JA. Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Development. 2004;75(5):1357–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Jacklin CN. The psychology of sex differences. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection theory: A user’s guide. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa E. Alerting, orienting, and executive attention: Developmental properties and sociodemographic correlates in an epidemiological sample of young, urban children. Child Development. 2004;75(5):1373–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology. 2000;41(1):49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky SH, Schafer JGB, Abrams MT, Goldberg MC, Flower AA, Boyce A, et al. fMRI evidence that the neural basis of response inhibition is task-dependent. Cognitive Brain Research. 2003;17:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky SH, Simmonds DJ. Response inhibition and response selection: Two sides of the same coin. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20(5):751–761. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. On inhibition/disinhibition in developmental psychopathology: Views from cognitive and personality psychology and a working inhibition taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:220–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, McCandliss BD, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Developmental Science. 2007;10:464–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, Norman MF, Farah MJ. Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children. Developmental Science. 2005;8(1):74–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich DS, Livesey DJ, Livesey EJ. Performance on Stroop-like assessments of inhibitory control by 4- and 5-year-old children. Infant and Child Development. 2010;19:252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Rothbart MK. Development of Short and Very Short forms of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2006;87(1):103–113. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8701_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush BK, Barch DM, Braver TS. Accounting for cognitive aging: Context processing, inhibition or processing speed? Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2006;13(3–4):588–610. doi: 10.1080/13825580600680703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Russell T, Overmeyer S, Brammer MJ, Bullmore ET, Sharma T, et al. Mapping motor inhibition: Conjunctive brain activations across different versions of go/no-go and stop tasks. NeuroImage. 2001;13:250–261. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin. 1965;64:91–107. doi: 10.1037/h0022371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallice T, Burgess PW. Deficits in strategy application following frontal lobe damage in man. Brain. 1991;114:727–741. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A, Riggs KJ. Conditions under which children experience inhibitory difficulty with a “button-press” go/no-go task. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2006;94:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Bauer E, Merz CJ, Zimmermann M, Reuter M, Plichta MM, et al. ADHD related behaviors are associated with brain activation in the reward system. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:426–434. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm L, Menon V, Reiss AL. Maturation of brain function associated with response inhibition. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(10):1231–1238. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towse JN, Lewis C, Knowles M. When knowledge is not enough: The phenomenon of goal neglect in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2007;96:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto S, Kuwajima M, Sawaguchi T. Developmental fractionation of working memory and response inhibition during childhood. Experimental Psychology. 2007;54:30–37. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169.54.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MC, Pennington BF, Groisser DB. A normative-develomental study of executive function: A window on prefrontal function in children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1991;7(2):131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Espy KA, Charak D. Using confirmatory factor analysis to understand executive control in preschool children: Latent structure. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(2):575–587. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Sheffield T, Nelson JM, Clark CAC, Chevalier N, Espy KA. The structure of executive function in 3-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2011;108:436–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe CD, Bell MA. Working memory and inhibitory control in early childhood: Contributions from physiology, temperament, and language. Developmental Psychobiology. 2003;44:68–83. doi: 10.1002/dev.10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock R, McGrew K, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III Brief Intellectual Ability Assessment. Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, He Y, Qinglin Z, Chen A, Li H. Gender differences in behavioral inhibitory control: ERP evidence from a two-choice oddball task. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:986–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Frye D, Rapus T. An age-related dissociation between knowing rules and using them. Cognitive Development. 1996;11(1):37–63. [Google Scholar]