Abstract

Background

Randomized clinical trials often encounter slow enrollment. Failing to meet sample size requirements has scientific, financial, and ethical implications.

Aims

We report interventions used to accelerate recruitment in a large multicenter clinical trial that was not meeting prespecified enrollment commitments.

Methods

The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST) began randomization in December 2000. To accelerate enrollment, multiple recruitment tactics were initiated, which included expanding the number of sites; hiring a Recruitment Director (May 2003); broadening eligibility criteria (April 2005); branding with a study logo, website, and recruitment materials; increasing site visits by study leadership; sending emails to the site teams after every enrollment; distributing electronic newsletters; and implementing investigator and coordinator conferences.

Results

From December 2000 through May 2003, 14 sites became active (54 patients randomized); from June 2003 through April 2005, 44 sites were added (404 patients randomized); and from May 2005 through July 2008, 54 sites were added (2044 patients randomized). During these time intervals, the number of patients enrolled per site per year was 1.5, 3.6, and 5.6. For the single years 2004 to 2008, the mean monthly randomization rates per year were 19.7, 38.1, 56.4, 53.0, and 54.7 (annualized), respectively. Enrollment was highest after recruitment tactics were implemented: 677 patients in 2006, 636 in 2007, and 657 in 2008 (annualized). The prespecified sample size of 2502 patients, 47% asymptomatic, was accomplished July 2008.

Conclusions

Aggressive recruitment tactics and investment in a full-time Recruitment Director who can lead implementation may be effective in accelerating recruitment in multicenter trials.

Keywords: Clinical trial, prevention, Carotid endarterectomy, Carotid stenosis, Carotid stenting, Stroke

Introduction

Successful randomized clinical trials (RCTs) require efficient organization, management, and marketing to ensure adequate enrollment.1–4 Failing to meet sample size requirements has scientific, financial, and ethical implications. Statistical power is compromised which undermines testing the trial’s primary hypothesis. Inefficient enrollment delays trial completion, leading to additional costs. Studies may be shut down by funding or regulatory entities before reaching meaningful conclusions.5, 6 Underenrollment can be unethical. Participants consent to the risks and inconveniences mandated by the study, and family members share in the inconveniences. If enrollment is not adequate for the study to achieve its aims, the participants have been subjected to the risks and inconveniences unnecessarily. These consequences can lead to mistrust of research by potential participants and so jeopardize enrollment in future studies.7

The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST) was designed to contrast the relative safety and efficacy of carotid artery stenting (CAS) versus carotid endarterectomy (CEA).8, 9 The protocol was approved by the institutional/ethics review boards (IRB) at participating sites. All participants provided written informed consent.

Aims

Enrollment in CREST was slower than required to achieve the predetermined sample size of 2500. Roadblocks included the extended process for credentialing of operators for the CAS procedure,10 delays by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to reimburse CAS,11 and suspension of enrollment from February to June 2002 due to a protection device failure. We describe recruitment tactics used in a large multicenter National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded stroke prevention trial that was not meeting prespecified enrollment commitments.8–11

Methods

In April 2003, the Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) was transferred to the CREST Administrative Center at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ). The IDE created the need for additional staff. Two Senior Clinical Research Associates were hired to carry out site start-up and management. In May 2003, a Recruitment Director was appointed to coordinate enrollment efforts across all centers. A Recruitment Center, composed of the study national Co-Principal Investigator (PI) and the Recruitment Director, was funded and established, centralizing the coordination of recruitment efforts.

CREST initially received NIH and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for 40 centers. Study leadership determined early in the enrollment phase that additional sites would be required. Approvals for 50 sites, then 60, 70, 110, 115, and 119 were obtained from October 2000 to June 2009. Development of a recruitment plan was required by each site.

In 2004, results of the Asymptomatic Carotid Stroke Trial (ACST)12 reported a benefit of CEA in asymptomatic patients similar to that shown in the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS).13 Because the majority of CEAs in the United States were being performed for asymptomatic disease, study leadership proposed to the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, NIH, and FDA and they approved that the CREST protocol be amended to include asymptomatic patients.8 The first asymptomatic patient was enrolled in April 2005. The Recruitment Director worked with each site to update recruitment tactics and materials for this new pool of potential patients.

Monitoring of enrollment was increased by the Recruitment Director. Status of low-enrolling sites, obstacles to recruitment, tactics for improvement, and timelines for enrollment targets were reported weekly to the Recruitment Committee. Action items for sites not meeting monthly recruitment goals for three consecutive months were discussed and implemented. Such actions might include telephone calls by the national PI to the local site PI followed by formal letters outlining the site’s enrollment rate and requesting a timeline for expected improvement. After six months of no improvement, a site could face suspension from enrollment until a written site-specific recruitment plan was presented to and approved by the committee.

The Recruitment Director and the Recruitment Committee developed new tactics (Table 1) that were tailored depending on the characteristics of the site (academic or a community-based), the medical specialty (and referral population) of the site PI, the size and location of the site (e.g. Canada), or upon the target population (e.g. women and minorities). Recruitment materials required approval of each site's IRB and the UMDNJ-IRB. The study logo was used on all CREST materials. Recruitment supply packages with enrollment tools (Table 1) such as the posters, study brochures, laminated pocket cards, and coordinator protocol fact sheets were developed and shipped to the sites on a monthly basis and/or as needed.

Table 1.

Summary of multiple tactics used simultaneously and repeatedly to accelerate recruitment.

| Enrollment Tactics |

|---|

|

The email congratulating individual CREST teams for each patient randomized was sent from the Recruitment Director and followed by an email from the national PI. The Recruitment Director also made personal calls on a rotating basis to coordinators to ascertain and address recruitment issues or obstacles. Over 120 site visits for the randomized phase of the study were made by either the national PI, the national Co-PI, the Recruitment Director, or the Senior Clinical Research Associates.

The Recruiter, a bimonthly newsletter, recognized enrollment achievements with photos of site teams. Updates regarding study protocol, training, data compliance, and additional recruitment tips were included. An enrollment summary report by site was attached, allowing sites to compare their randomization rates.

The planning of the annual CREST Principal Investigators’ conferences and the annual coordinator conferences as well as more frequent telephone conferences focused on protocol updates, protocol compliance, training, and the status of the trial. New recruitment tools, women and minority recruitment, issues or obstacles to enrollment, and patient retention were also included.

The CREST website included a section dedicated to the general public and provided a study overview. Participating sites with PI and Coordinator contact information were listed in a directory, allowing potential participants to locate centers closest to their area. Another section solely for investigators and coordinators required a login and password. The “Recruiting Tools” section provided links for download of recruitment materials such as the template letters, press releases and newspaper advertisements, slide sets, and the Coordinator Fact Sheet. Information regarding the informed consent process, recruitment tactics, tips for improving enrollment of women and minorities, and a product overview by the manufacturer of the carotid stent and embolic protection systems were also included.

Results

Patients were randomized from December 21, 2000 to July 18, 2008 (Table 2). From December 2000 through May 2003, the month the Recruitment Director was hired, 14 sites became active, and 54 patients were randomized. The mean monthly randomization rate was 1.8. From June 2003 through April 2005, the month asymptomatic patients became eligible, 44 active sites were added, and 404 patients were randomized. The mean monthly randomization rate was 17.6. From May 2005 through July 2008, 54 active sites were added, and 2044 patients were randomized. The mean monthly randomization rate was 52.4. During these three time periods, the number of patients enrolled per site per year was 1.5, 3.6, and 5.6. The costs of the enhanced enrollment activities from the beginning of 2003 until completion of enrollment were considerable with personnel costs exceeding $770,000 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Notable study activities influencing recruitment and number of active sites, yearly enrollment, monthly average rate of enrollment, and average enrollment per site per year from 2000 to 2008.

| Year | Activity | Number of Active Sites |

Yearly Enrollment | Monthly Average Rate of Enrollment |

Average Enrollment per Site per Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sx | Asx | Sx+Asx | Sx | Asx | Sx+Asx | Sx | Asx | Sx+Asx | |||

| 2000 | Randomization begins December 2000. |

1 | 2 | NA | 2 | 2 | NA | 2 | 2 | NA | 2 |

| 2001 | 1 | 8 | NA | 8 | 0.7 | NA | 0.7 | 8 | NA | 8 | |

| 2002 | Failure of protection device - study halted February 2002 to June 2002. |

8 | 14 | NA | 14 | 1.2 | NA | 1.2 | 1.8 | NA | 1.8 |

| 2003 | Full-time Recruitment Director begins May 2003. |

34 | 114 | NA | 114 | 9.5 | NA | 9.5 | 3.4 | NA | 3.4 |

| 2004 | 49 | 236 | NA | 236 | 19.7 | NA | 19.7 | 4.8 | NA | 4.8 | |

| 2005 | Inclusion of asymptomatic patients February 2005. |

85 | 246 | 211 | 457 | 20.5 | 17.6 | 38.1 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 5.4 |

| 2006 | Majority of enrollment mechanisms implemented (and highest enrollment for a 1-year period) December 2006. |

103 | 278 | 399 | 677 | 23.2 | 33.3 | 56.4 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 6.6 |

| 2007 | 111 | 265 | 371 | 636 | 22.1 | 31.0 | 53 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 5.7 | |

| 2008 | Enrollment of 2502 is achieved. |

112 | 290* | 367* | 657* | 24.2* | 30.6* | 54.7* | 2.6* | 3.3* | 5.9* |

Sx=Symptomatic; Asx=Asymptomatic; NA=not applicable (asymptomatic patients were not eligible for enrollment into CREST until April 2005).

Annualized

Table 3.

Selected Costs for Enrollment in CREST (May 2003 – July 2008).

| Total Costs | Estimated Costs for Enrollment Activities* No. (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Salaries and Fringe Benefits | ||

| Recruitment Director | 245,518.91 | 245,518.91 (100) |

| Research Associates | 1,571,060.34 | 314,212.06 (20) |

| Co-Principal Investigator | 426,838.24 | 213,419.12 (50) |

| Printing Materials | 6,000.00 | 6,000.00 (100) |

| Teleconferencing | 6,347.29 | 1,269.46 (20) |

| Website | 7,073.00 | 7,073.00 (100) |

| Total | 787,492.55 | |

The numbers in this column are estimates of selected costs for enrollment activities in CREST. They do not represent all enrollment costs.

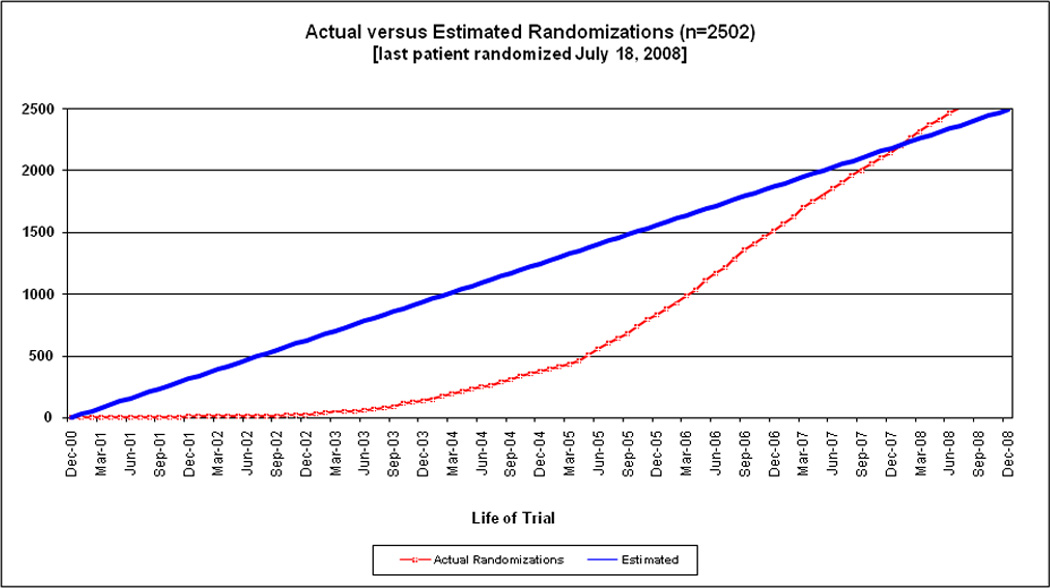

For the five years (2004–2008) following hiring of the Recruitment Director, the mean randomization rates per month were 19.7, 38.1, 56.4, 53.0, and 54.7 (annualized). Enrollment was highest during the years 2006 (n=677), 2007 (n=636), and 2008 (n=657, annualized), following implementation of new recruitment tactics and inclusion of asymptomatic patients. Actual versus estimated randomizations for the enrollment period are provided in the Figure. The maximum number of patients randomized in a single month was 76 in August 2006 (97 active sites). Ten subjects were enrolled in a single day on June 8, 2007 (108 active sites).

Figure.

CREST actual versus estimated randomizations (n=2502) (last patient randomized July 18, 2008).

Of the 119 approved sites, 117 enrolled at least one participant. The median number of enrollments per site was 16, interquartile range 6–27. Three sites individually enrolled >100 participants. The leading center was a university hospital (Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland OR, Wayne Clark, MD, PI), second was a community hospital (Central Baptist Hospital, Lexington, KY, William Brooks, MD, PI), and third was a city hospital in Canada (CHA, Hôpital de l'Enfant-Jésus, Québec QC, Ariane Mackey, MD, PI). Eight sites enrolled >50 participants. Forty-five sites enrolled < 10; as a result of site-recruitment monitoring, 59 sites received warning letters for underenrollment (28 received more than one warning letter), 11 sites were suspended (one site more than once), eight sites were reinstated after they provided a written plan to improve enrollment, and three sites were permanently suspended from further enrollment. Among the 2502 randomized participants, 1321 (53%) were symptomatic, 872 (34.9%) were female, and 234 (9.4%) were minority by race ethnicity or race-ethnicity.

Discussion

Our results suggest that increasing the number of clinical sites, establishing a full-time Recruitment Director, broadening study eligibility, and initiating multiple tactics to enhance enrollment were complementary and effective in achieving the required sample size of 2502 in CREST.

The expansion of approved sites from 40 to 119 was likely the most important tactic for successful enrollment. The original 40 sites were selected because they were thought to be the best with regard to quality and enrollment. The data (Table 2) suggest, however, that the addition of new sites never resulted in a decline in enrollment as judged by enrollment per site per month. The new sites were as productive as the original sites despite the rigorous site selection process in place in 2000. We suggest that the enthusiasm of new teams, the availability of a new treatment (CAS—reimbursable within CREST14), and the efforts and resources of the Recruitment Director and the CREST team combined for effective site expansion.

The effectiveness of a full-time Recruitment Director is also supported by the results (Table 2, Figure). The pace of enrollment increased shortly after the Recruitment Director was hired, and increasing enrollment continued before eligibility of asymptomatic patients could be established study-wide. In addition, site selection and start-up were accelerated, as well as IRB approval and site implementation of recruitment tools. Ongoing daily feedback to the sites following an enrollment became feasible. In CREST, the model was to centralize supplementary personnel and mechanisms for recruitment. In other trials, the utility of where such efforts should be concentrated will depend on the design of the trial. For example, in the NINDS tPA Stroke trial,15 there were a smaller number of sites, eight, and so it was feasible (and effective) to have a recruitment-dedicated professional at each site. In a trial with larger numbers of sites, resources may be insufficient for the NINDS tPA model, and so the centralized model may be more effective.

Widening eligibility in CREST to include asymptomatic patients also drove enrollment. The principle argument for inclusion was to increase the generalizability of the CREST results, to inform clinical decision-making for asymptomatic patients. Adding asymptomatic patients was expected to increase enrollment, and a rise in enrollment would have occurred even without increasing the number of sites or hiring a Recruitment Director. However, we were encouraged in that enrollment for symptomatic patients did not decline and the rate of enrollment of the asymptomatic patients increased after 2005, suggesting that site expansion and the Recruitment Director efforts continued to add value.

Multiplicity in tactics and tools is likely more important than the best tactics and tools. Many of the recruitment interventions we report are not unique, having been used in other trials. Rather, we suggest that our accelerating enrollment was due in substantial proportion to the number of tactics and tools that could be exported to the sites. Patients and sites from CREST, and in other RCTs, are heterogeneous. Individual tactics and tools will vary in effectiveness, so the more the better. We also suggest that implementation of multiple mechanisms for recruitment requires full-time personnel in a large multicenter RCT. Even a simple patient brochure is surprisingly time-consuming in inception, design, regulatory approval, and distribution.

Repeated communication to the centers in a multicenter trial is essential. Not uncommonly the individual centers are enrolling only one patient per month, or less. In that context, the personnel in the typical multi-shift clinic or hospital, and even some investigators, can forget enrollment criteria or that a particular trial is enrolling. The impression of the Recruitment Director, the CREST PI and co-PI, and other team members was that repetition was exceptionally effective. The message is also important. Recognizing individual investigators and coordinators at the sites for a job well done is not soon forgotten, particularly when that recognition is timely. Soliciting feedback from the sites, which can be followed by actions from study leadership, cements strong relationships. In CREST, protocol amendments were instituted, which were based upon feedback from the clinical sites, including changes to case report forms, follow-up visit schedules, and types of visits. Confidence that their concerns were being heard and acted upon allowed for candid discussions with investigators and coordinators regarding site-specific recruitment challenges and initiatives to improve enrollment.

Large RCTs commonly experience slow or underenrollment. A review of 114 trials reported that less than one-third were successful in obtaining targeted enrollment within the original prespecified enrollment period, and about one-third required extensions.16 Characteristics of the study site, whether academic or community-based, will often dictate the appropriate resources for effective enrollment.17 In CREST, sustaining an average yearly randomization rate of 607 over the last four years of the enrollment period attenuated the negative budgetary consequences of enrollment extending beyond mid-2008. More importantly, achieving the prespecified sample size maintained the scientific integrity of the trial. In so doing, successful enrollment also fulfilled the ethical obligations to the patients and to their family members for the risks and inconveniences of participation.

Of note, for trial design and peer review of grant proposals, the original estimates of site productivity provided by CREST leadership based upon the site estimates were inaccurate. For example, the annual rate of enrollment per site per year was projected to be 25 with 40 enrolling centers. The best annual rate of enrollment per site per year ever sustained for CREST was 6.6 with 103 active sites, only 26% of the predicted rate (Table 2). We hypothesize that over-estimating enrollment is a common limitation of RCT proposals to NIH and other funding institutions. The investigators initiating the proposals are likely to anticipate better peer review if they incorporate fewer sites, shorter enrollment periods, and less expensive total costs. Potential sites are likely to overestimate as well. The site investigators wish to be selected, particularly if participation is tied to CMS and other third-party reimbursement. Our results suggest that critical examination of recruitment methodology and capability should receive greater prioritization at peer review of large multicenter RCT proposals.

It should be noted that in CREST data regarding site-level or study-wide variables that may have affected recruitment were not systematically collected (e.g. turnover of approved personnel, temporary shut down of enrollment due to technical problems, availability of certified physicians to perform the procedure, times for IRB approval of protocol changes and recruitment materials). Screening logs were maintained early, but quality varied, and so the logs were not prioritized. Implementing CMS reimbursement varied considerably by region, state, and hospital. The dates for implementation of the inclusion of asymptomatic patients also varied considerably by site.

Conclusions

Increasing the number of enrolling centers, adding a Recruitment Director, widening eligibility, and expanding recruitment tactics were the drivers for achieving the prespecified sample size in CREST. From 1977 to 2007, the NINDS at the NIH funded 28 phase 3 stroke trials randomizing over 44,000 participants.18 Future trials may require greater numbers of participants.18 Scientific, ethical, and financial success will depend upon improved strategies and tactics to maximize enrollment into these RCTs.

Acknowledgments

None

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS 038384); supplemental funding from Abbott Vascular Solutions, Inc. (formerly Guidant).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Warlow C. How to do it. Organise a multicentre trial. BMJ. 1990;300:180–183. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6718.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrell B, Kenyon S, Shakur H. Managing clinical trials. Trials. 2010;11:78. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrell B. Efficient management of randomised controlled trials: nature or nurture. BMJ. 1998;317:1236–1239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis D, Roberts I, Elbourne DR, et al. Marketing and clinical trials: a case study. Trials. 2007;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroen AT, Petroni GR, Wang H, et al. Preliminary evaluation of factors associated with premature trial closure and feasibility of accrual benchmarks in phase III oncology trials. Clin Trials. 2010;7:312–321. doi: 10.1177/1740774510374973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, et al. Protected Carotid-Artery Stenting versus Endarterectomy in High-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1493–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpern SD, Karlawish JHT, Berlin JA. The Continuing Unethical Conduct of Underpowered Clinical Trials. JAMA. 2002;288:358–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brott TG, Hobson RW, II, Howard G, et al. Stenting versus Endarterectomy for Treatment of Carotid-Artery Stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheffet AJ, Roubin G, Howard G, et al. Design of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting Trial (CREST) Int J Stroke. 2010;5:40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins LN, Roubin GS, Chakhtoura EY, et al. The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial: Credentialing of Interventionalists and Final Results of Lead-in Phase. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobson RW, II, Howard VJ, Brott TG, et al. Organizing the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST): National Institutes of Health, Health Care Financing Administration, and Industry funding. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2001;2:160–164. doi: 10.1186/cvm-2-4-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1491–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive committee for the asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis study. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broderick JP. The Challenges of Intracranial Revascularization for Stroke Prevention. Editorial. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1108394. 10.1056/nejme1108394; published on September 7, 2011 at NEJM.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell MK, Snowdon C, Francis D, Elbourne D, et al. Recruitment to randomized trials: strategies for trial enrollment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:iii, ix–105. doi: 10.3310/hta11480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J. The Art and Science of Community-Based Clinical Trial Recruitment. MONITOR. 2007:21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marler JR. NINDS Clinical Trials in Stroke – Lessons Learned and Future Directions. Stroke. 2007;38:3302–3307. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.485144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]