Abstract

Purpose

Femoral shaft fracture following birth in newborns is a very rare injury. However, the risk factors for, mechanism of and management of these injuries remain a matter of debate. We describe our observations in a tertiary centre.

Methods

Ten cases of femoral shaft fracture encountered during a study period from January 2005 to December 2009 were evaluated. The demographic details, risk factors during birth, systemic illness, mode of delivery, type of fracture and management used were documented, and an analysis was performed.

Results

Mean gestational age was 37.2 weeks. Mean time to diagnose was 4 days. Two patients had subtrochanteric fracture, and eight patients had mid-shaft fracture. Most patients had breech presentation and had been born by Caesarean section. All patients showed complete union at the end of 4 weeks. No residual angulation or limb length discrepancy was noted after mean follow-up of 5 years.

Conclusions

Thorough clinical examination and proper orthopaedic consult in the event of doubtful presentation help in early diagnosis and management. These fractures have good prognosis at long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Neonate, Birth injuries, Femoral shaft fracture, Caesarean, Breech

Introduction

Birth injuries occurring due to trauma during the process of childbirth are very rare [1]. They are a cause of significant neonatal morbidity despite improved obstetric and perinatal care, more so in developing countries. The spectrum of birth injuries includes a simple bruise, swelling, forceps scar or loss of nerve and motor function or rarely a fracture. An estimated three-quarters of all long-bone fractures during birth are ascribed to vaginal breech deliveries [2]. Other risk factors include low birth weight and large foetus. The role of Caesarean delivery in reducing the outcome of these injuries is a matter of debate [3, 4]. Though numerous reports regarding femoral shaft fracture have been published, the associated risk factors, characteristics and treatment modalities have not been well elucidated. Our present study, consisting of a case series of ten newborns with fracture of femur, aims to throw light on its associated factors and treatment strategies.

Methods

We encountered ten cases of fracture femur in newborns at our institute from January 2005 to December 2009. Six of them were born in our obstetric department and were detected when an expert orthopaedic consult was made. The other four cases were referred to our outpatient department from peripheral hospitals for further medical care. These ten cases were analyzed from the data recorded. The collected data included demographic specifics such as gender, birth weight, gestational age, presentation and mode of delivery, site of the fracture, other injuries suffered, coexisting medical disease along with treatment modality followed (Fig. 1).

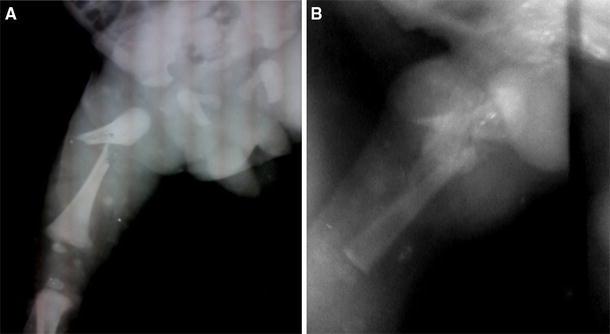

Fig. 1.

Radiographs of a 3-day-old child showing a subtrochanteric spiral fracture (a) sustained following a difficult Caesarean delivery. Radiograph after 3 weeks showing abundant callus formation (b) after strapping the thigh to abdomen

Results

The cohort of ten cases with birth-related fracture femur included six male and four female infants. Mean gestational age was 37.2 weeks (range 34–42 weeks). We had one child born as post-term baby at 42 weeks and one pre-term birth at 34 weeks. The mean birth weight of the infants was 2,691 g (range 2,050–3,850 g). Mean time duration to diagnosis was 4 days (1–14 days). All six cases born in our obstetric department were diagnosed before the second day. Two patients had fractures in the subtrochanteric region, and eight patients had fracture in the middle one-third of the shaft of femur. There was one newborn who had suffered a fractured humerus along with the femur. One infant was provisionally diagnosed to have osteogenesis imperfecta suggested by blue sclera and family history of multiple fractures in siblings and his father. Two infants were born to mothers with diabetes, one mother was aged >40 years, two mothers were multipara with 3 and 4 children, respectively. No history of drug abuse or use of medications other than for diabetes was present. No child had a precipitous delivery.

Regarding mode of delivery, four infants had vaginal delivery and six were delivered by Caesarean section. In the cases delivered vaginally, presentation of the foetus was cephalic in two and breech in two. One case which required the assistance of forceps had suffered a fractured humerus along with the fracture of the femur. In the six infants delivered by Caesarean section, presentation was breech in five and cephalic in one. Five of them were planned for elective C section and one underwent emergency C section because of obstructed labour.

Treatment modality was decided depending on the site of fracture and angulation at the site. Femoral fractures in the subtrochanteric region were managed by strapping of the thigh to abdomen, while fractures of the shaft were managed in a toe–groin cast. The fracture of humerus in one newborn was managed by limb–body strapping (keeping the arm by the side of the body with a strap). All patients were followed on a weekly basis in the outpatient department. All of them were pain free by 4 weeks, and healing had occurred by then (Table 1). There was no limb length discrepancy or residual angulation noted at further follow-up with mean duration of 60 months (range 24–84 months).

Table 1.

Demographic details of the newborns

| Infant | Gender | Time to diagnosis (days) | Birth weight (g) | Gestational age (weeks) | Presentation | Mode of delivery | Site of fracture | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 14 | 2,050 | 34 | Cephalic | Vaginal | Mid-shaft | Cast |

| 2 | Female | 1 | 2,200 | 38 | Breech | Vaginal | Mid-shaft | Cast |

| 3 | Male | 1 | 2,650 | 36 | Breech | Vaginal | Mid-shaft | Cast |

| 4 | Male | 2 | 2,120 | 36 | Cephalic | Vaginal | Mid-shaft | Cast |

| 5 | Female | 2 | 2,900 | 38 | Breech | Caesarean | Subtrochanteric | Strapping |

| 6 | Female | 6 | 2,450 | 36 | Breech | Caesarean | Mid-shaft | Cast |

| 7 | Male | 4 | 2,750 | 37 | Breech | Caesarean | Mid-shaft | Cast |

| 8 | Female | 1 | 3,850 | 42 | Breech | Caesarean | Subtrochanteric | Strapping |

| 9 | Male | 2 | 3,100 | 37 | Breech | Caesarean | Mid-shaft | Cast |

| 10 | Male | 7 | 2,840 | 38 | Cephalic | Caesarean | Mid-shaft | Cast |

Discussion

Fractures may occur due to significant mechanical forces at any point of time in the series of events in childbirth. The most common fracture usually encountered is that of clavicle. Fracture of femur is considered rare in newborns and has been described with difficult deliveries. The reported incidence varies between 0.13 and 0.077 per 1,000 deliveries [3, 4]. The earliest case of femoral shaft fracture in a newborn was reported in 1922 following a difficult breech delivery [5]. Since then, much literature has been published regarding the possible aetiology, risk factors and management of this injury.

The mechanisms of injury to femur have been well described with vaginal delivery. It may happen in the context of malpresentation, low birth weight, macrosomic baby and difficult or precipitous delivery [4]. Caesarean section is presumed to reduce the risk of fractures. This consideration has been catechized in many reports in the literature [3]. The prevalent use of low segment vertical incision to reduce maternal morbidity compounded by difficult indications such as breech presentation or obstructed labour may increase the incidence of neonatal injuries in Caesarean section [3]. This is even obvious from the evidence in our study, with 60 % incidence in Caesarean section, being particularly predominant with breech presentation.

Other risk factors associated with this injury include osteogenesis imperfecta, disuse osteoporosis following prolonged immobilization and osteopaenia of prematurity [4]. We had one patient with osteogenesis imperfecta who had a fracture of shaft of femur, who was treated with toe–groin cast and had complete union. He was then treated with intravenous pamidronate. This patient has been under our follow-up for 3 years and had one episode of fracture shaft humerus. We, however, could not analyze the role of maternal comorbid factors on the risk of fracture in view of the small sample size.

The role of gender in fracture risk has not been assessed in the published literature. In the study of 11 cases published by Givon et al. [6], most of the neonates were female (n = 7). However, we had more males (n = 6) than females (n = 4). Therefore, we could not draw any conclusions on the possible role of gender on fracture risk.

The mean gestational age at diagnosis in our patients was 37.2 weeks. We had only one post-term and one pre-term baby, the rest being full term. The mean birth weight of the babies was 2,691 g. Of the ten, four of them were <2.5 kg, considered to be low birth weight. Thus, earlier speculated risk factors such as macrosomic post-term or pre-term babies might have less bearing whereas low birth weight in full-term pregnancies might prove to be influential in our country.

Diagnosis of femoral fracture was made after a mean period of 4 days (range 1–14 days) in our study. This is similar to the time period in other tertiary institutes [3, 4]. However, we had one patient who was delivered outside and presented to our outpatient department after a period of 14 days. Detailed history revealed that neglect due to ignorance of the parents and lack of hospital nearby in their locality was the cause of the delay.

The mechanism of injury has been postulated to be most commonly torsional injury leading to spiral fracture of the shaft of femur [4]. Most of the fractures in our series were of the same type. In the case of vaginal delivery, excessive traction on the leg when the breech is fixed at the pelvis can lead to fracture of the femoral shaft. Though Caesarean section was postulated initially to decrease this pattern of injury [7], many contrary reports have shown a reverse incidence [3, 4]. One reason could be the decreased space for manoeuvrability of obstetric procedures in these patients [8]. Other causes may include poor relaxation, poor delivery techniques and small incision.

Several treatment modalities were used for treatment in this study. The basic principle underlying these is strict immobilization of the femoral shaft. The proximal fragment is flexed, abducted and externally rotated in case of subtrochanteric fracture of femur. Simple strapping of the thigh to the trunk used in our case functions in the same way as a Pavlik harness to achieve reduction by bringing the distal fragment in alignment with the proximal one. Strapping thus has advantages of low cost, ease of application, adjustability and ease of reduction. Fractures of the shaft of femur are usually encountered with minimal angulation and will be managed with toe–groin cast until the fracture becomes sticky. All patients showed good healing with callus formation and showed evidence of union after an average of 4 weeks. This definitely exemplifies the good prognosis of these fractures and lack of long-term disability.

Our study does have some limitations. Most of our cases were diagnosed only when a consult was sent to us by the neonatologists based on suspicion, leading to a possibility of missing an occult fracture. A thorough screening protocol by the neonatologist in the event of a difficult delivery would be quite helpful. Being a tertiary institute with a selective admission policy, our patient sample size was not representative of the general population. Combined with a small patient sample size, our findings may not be generalized.

In conclusion, femoral fractures following delivery, though rare on presentation, should be looked out for, especially in difficult Caesarean sections. Thorough clinical examination and proper orthopaedic consult in the event of doubtful presentation would help. These fractures have very good prognosis and show complete healing following immobilization.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Cunningham FG, Leveno KL, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC III, Wenstrom KD (eds) (2005) Section IV. Labor and delivery, chapter 25: CESAREAN delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. In: Williams Obstetrics, 22nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, 589–599

- 2.Curran JS. Birth associated injury. 5. Clin Perinatol. 1981;8:111–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toker A, Perry ZH, Cohen E, Krymko H. Cesarean section and the risk of fractured femur. IMAJ. 2009;11:416–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris S, Cassidy N, Stephens M, McCormack D, McManus F. Birth associated femoral fractures: incidence and outcome. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(1):27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrenfest H. Birth injuries of the child. New York: Appleton Century Crofts; 1922. p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Givon U, Sherr-Lurie N, Schindler A, Blankstein A, Ganel A. Treatment of femoral fractures in neonates. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9(1):28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes AD, Van Geem TA. Fractured femur of the newborn at caesarian section. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1985;30:203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rijal L, Ansari T, Trikha V, Yadhav CS. Birth injuries in caesarian sections: cases of fracture femur and humerus following caesarian section. Nepal Med Coll J. 2009;11(3):207–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]