Abstract

Objectives

To describe the risk factors associated with death in pregnant women with severe pandemic H1N1 infection.

Design

Case–control study.

Setting

Anhui, China.

Participants

A total of 46 pregnant women with severe pandemic H1N1 infection were studied during June 2009–April 2011.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

All the cases were confirmed by the clinicians and epidemiologists together based on the positive laboratory result.

Results

Of the seven pregnant women who died of the pandemic H1N1 infection, five (70%) cases were in their third trimester. Twenty-nine (63%) cases from the surviving group were admitted to hospital within 3 days after the onset of symptoms, while only one (2%) case from the death group took the earliest admission 2 days after the onset. There was a significant difference on how soon to be admitted between the death and the surviving groups (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.68). The median time of administrating corticosteroids was 5 days after the onset in the death group and 3 days in the surviving group showing no significant difference between them (p=0.056).

Conclusions

For the pregnant women with severe p(H1N1) infection, the risk factors associated with death were as follows: the delay of antiviral treatment and being in the third trimester. The corticosteroids therapy appeared to have no effects on preventing the cases from death.

Article summary

Article focus

Early antiviral treatment might decrease the mortality of the pregnant women with severe p(H1N1) infection.

Being in the third trimester is a risk factor associated with death of the severe p(H1N1)-infected pregnant women.

Corticosteroid therapy appeared to have no effect on preventing the severe p(H1N1)-infected pregnant women from death.

Key messages

The results showed that the pregnant women with severe p(H1N1) infection who took earlier antiviral treatment would more likely reduce the possibility of death.

Most of the pregnant women who died of the pandemic H1N1 infection were in their third trimester.

Whether to be given corticosteroids therapy showed no significant influence on the prognosis of the pregnant women with severe p(H1N1) infection.

Strengths and limitations of this study

All the severe cases with p(H1N1) infection were confirmed carefully by a panel consisting of the experts from hospitals, CDCs on the basis of laboratory detection so the confirmation of the cases was credible.

However, our estimates may not be generalised to the rest of the severe pregnant cases infected by pandemic H1N1 as the relatively small sample and lack of the cases' underlying medical conditions limited the ability of extrapolation.

Introduction

As in the documented influenza epidemics and pandemics, particularly the 2009 pandemic A (H1N1), pregnant women appear to be at increased risk of severe diseases.1–8

The effects of influenza during pregnancy have been noted in previous pandemics, particularly the increased mortality in pregnant women compared with the general population.9

Health Ministry of China issued ‘Diagnosis and Treatment of Pandemic Influenza A(H1N1) (Trial Second Edition)’ on 10 July 2009 declaring that the pregnant women belonged to the highest risk group of pandemic influenza A(H1N1) infection.

From 19 June 2009 to 25 April 2011, 43% of the total cases with severe p(H1N1) infection reported to a web-based Anhui provincial influenza surveillance system were pregnant. Fifteen per cent of the severe p(H1N1) cases during pregnancy or puerperium died.

How to decrease the mortality of the p(H1N1) severe cases, in particular to the pregnant women, has been a crucial problem, even though the authority of public health in China had adjusted the control measures and administrative strategies for controlling the p(H1N1) epidemics based on the different stages of the pandemic. However, the global H1N1 influenza pandemic disproportionately affected pregnant women, drawing attention to the fact that although they need safe and effective medical treatment, they have always been a marginalised study population.10 To know more about the risk factors associated with pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection, we conducted an individual investigation to all the cases reported to the Anhui provincial influenza surveillance system from 19 June 2009 to 25 April 2011.

This article aimed to describe the characteristics of the pregnant women with severe p(H1N1) infection and the possible risk factors associated with their death.

Methods

Data sources and participants

Since the Health Ministry of China declared the first p(H1N1) case reported occurring in mainland of China on 11 May 2009, the national influenza surveillance system had been further enhanced and expanded to more areas all over the country. Until June 2009, China had set up 282 national sentinel hospitals in southern China and 274 in northern China. Anhui province, located in southern China, had established 25 (9% of all the southern provinces in China) national sentinel hospitals in all 17 prefecture cities since June 2009.

All the professionals in the sentinel hospitals and Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDCs) of Anhui were trained on the field epidemiological investigation by using the uniform questionnaire designed by the China CDC. Cases diagnosed by the local sentinel hospitals were reported to the local CDC, and their samples, collected by the clinicians, were submitted to the network laboratory of the national influenza surveillance system to perform the laboratory test. The severe case needed to be confirmed by a panel consisting of the local sentinel hospital's clinicians and CDC's epidemiological experts. The severe cases were investigated by the local CDC epidemiologists using the uniform questionnaire in the appendix of ‘National p(H1N1) influenza surveillance guideline (the second edition)’ and then submitted to ‘the Chinese Influenza Surveillance Information System’.

A review was conducted for all the severe cases of p(H1N1), pregnant or postpartum, reported to Anhui provincial influenza surveillance system from 19 June 2009 to 25 April 2011. However, the pregnant women's underlying medical conditions, particularly of the dead cases, could not have been collected.

Case definition

A case of p(H1N1) infection was defined as a patient with influenza-like symptoms confirmed by one or more of the following: reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) or real-time PCR; isolation of p(H1N1) virus; fourfold or more increase of the specific antibody of the case's double blood serum.

A severe case of p(H1N1) infection was defined as a case with at least one of the following symptoms: high fever more than 3 days; purulent blood-stained sputum or chest pain; dyspnoea or cyanotic lips; alerted mental (unresponsive, lethargy, restlessness or eclampsia); severe vomiting, diarrhoea and dehydration; pneumonia by imaging examination; quick increase of cardiac enzyme, such as creatine kinase, creatine kinase isozymes; respiratory failure; infective toxic shock; multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; admission to intensive care unit.

A fatal case of p(H1N1) infection was defined as confirmed p(H1N1) infection in a severe case who died or whose death certificate listed p(H1N1) influenza as a major or underlying cause of death.

A severe pregnant case was a severe case during pregnancy. Patients were excluded if they had been treated as outpatients or in emergency rooms, had duration of hospitalisation <24 h or there was an incomplete record of clinical outcome.11

All the pregnant cases were divided into two groups: death and surviving groups. The case–control studies were conducted between the two groups to know their difference in characteristics and treatment.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted using SPSS V.15.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for Windows. The median was calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test, a Fisher's exact test or an independent sample t test.

Results

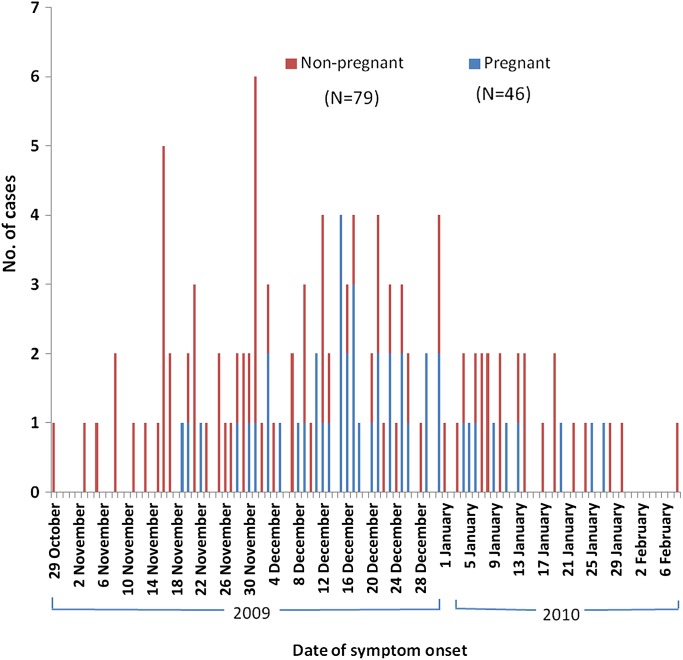

Of 3436 cases reported from 19 June 2009 to 25 April 2011, 126 (3.7%) were severe cases, including 46 (37%) pregnant women, one (1%) postpartum woman and 79 (63%) non-pregnant cases. Of the total 126 severe cases, seven (15%) pregnant cases and seven (9%) non-pregnant cases died. Dates of symptom onset for all the severe cases ranged from 29 October 2009 to 8 February 2010 and are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Numbers of women who were hospitalised with or died of p(H1N1) influenza, as reported to Anhui Provincial CDC, during the period from 19 June 2009 to 25 April 2011 according to the pregnancy status and date of symptom onset.

The severe cases with p(H1N1) infection reported from 29 October 2009 through 8 February 2010 peaked on 1 December 2009 with a decrease, mainly occurring in the mid-November 2009 through the end of December 2009, and the pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection were reported mainly in December 2009.

Association between mortality and trimester

Of the 46 pregnant women, six (13%) were in the first trimester, five (11%) in the second trimester and 35 (76%) in the third trimester. Of the seven pregnant women who died of the p(H1N1) infection, five (70%) were in the third trimester.

Association between mortality and age

The age of pregnant women varied from 18 to 31 years in the death group and from 18 to 27 years in the surviving group, and no significant difference in age was found between the two groups (p=0.12). The median age was 21 years in either death or surviving group showing no significant difference between them (p=0.96). The results are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Association between characteristic, treatment and mortality of 46 pregnant cases with severe p(H1N1) infection

| Variable | Group |

Value |

||

| Death (N=7) | Surviving (N=39) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Characteristic | ||||

| Age in years, n (%) | ||||

| 18–25 | 5 (11) | 34 (74) | 2.72* (0.41 to 18.10) | |

| 26–32 | 2 (4) | 5 (11) | ||

| Median age (range) | 21 (18–31) | 21 (18–27) | 0.96† | |

| Days from onset to hospital admission, n (%) | ||||

| 0–3 | 1 (2) | 29 (63) | 0.09‡ (0.01 to 0.68) | |

| 4–7 | 6 (13) | 10 (22) | ||

| Median days (range) | 4 (2–7) | 2 (0–7) | 0.004† | |

| Antivirus use | ||||

| Days from onset to first dose of antiviral therapy, n (%) | 0.06‡ (0.01 to 0.41) | |||

| 0–3 | 1 (2) | 32 (70) | ||

| 4–8 | 6 (13) | 7 (15) | ||

| Median days (range) | 5 (2–8) | 3 (0–7) | 0.0054§ | |

| Days of antiviral therapy | 0.95* (0.21 to 4.30) | |||

| 1–3 | 2 (4) | 11 (24) | ||

| 3–11 | 5 (11) | 26 (57) | ||

| Median days (range) | 5 (1–11) | 5 (2–11) | 0.32‡ | |

| Hormone | ||||

| Days from onset to hormone use, n (%) | 0.25‡ (0.03 to 1.86) | |||

| 1–3 | 1 (4) | 11 (41) | ||

| 4–9 | 5 (19) | 10 (38) | ||

| Median days (range) | 5 (1–9) | 3 (0–9) | 0.056§ | |

The p value was calculated by a two-sided Fisher's exact test.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

One-sided Fisher's exact test.

One-sided independent sample t test.

Association between mortality and admission time

The time interval from onset to death ranged from 6 to 31 days and the median was 18 days in the death group, while in the surviving group, the duration of onset to recovery varied from 5 to 39 days and the median was 14 days.

Twenty-nine (63%) cases in the surviving group were admitted to hospital within 3 days after the onset, while only one (2%) case in the death group took the earliest admission 2 days after the onset. There was a significant difference on how soon to be admitted between the death and the surviving groups (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.68). Median time of admission to hospital in the death group was 4 days after the onset and in the surviving group was 2 days. The difference between them was significant (p=0.004) and is shown in table 1.

Association between mortality and antiviral treatment

The pregnant women who died of the severe p(H1N1) infection were given antiviral treatment 2–8 days after the onset, and the surviving pregnant cases were prescribed antiviral drugs on the first day of onset to 7 days after the onset. Seventy per cent of surviving cases were given antiviral drugs within 3 days after the onset, but only 2% of the death cases were treated by antiviral drugs over the same time period and the other death cases were all treated more than 3 days after the onset. There was a significant difference in time for being given antiviral drugs between the death and surviving groups (OR 0.06, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.41). The median of time interval from onset to antiviral treatment was 5 days in the death group and 3 days in the surviving group showing a significant difference (p=0.0054).

Antiviral drugs were given in a range of 1–11 days in the death cases and 2–11 days in the surviving cases. Four per cent of the death cases and 24% of the surviving cases took the antiviral drugs no more than 3 days. There was no significant difference of time duration from onset to antiviral treatment between the death and the surviving groups (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.21 to 4.30), and the median was 5 days either in the death group or in the surviving group. No significant difference appeared between the death and the surviving groups in the median of time duration for antiviral treatment (p=0.32). The results are shown in table 1.

Associations between mortality and corticosteroids therapy

Corticosteroids therapy was given in a range of 1–9 days after the onset in the death cases and on the first day of onset to 9 days after the onset in the surviving cases. One (4%) death case and 11 (41%) surviving cases took corticosteroids within 3 days after the onset, and there was no significant difference in time duration from onset to corticosteroids therapy between the death and the surviving groups (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.86). The median of time duration from onset to corticosteroids therapy was 5 days in the death group and 3 days in the surviving group showing no significant difference between them (p=0.056).

Corticosteroids therapy was given in a range of 2–17 days in the death cases and 1–5 days in the surviving cases. Three (7%) death cases and 14 (30%) surviving cases were treated by corticosteroids therapy in time ranging from 3 to 5 days. There was no significant difference in time duration from onset to corticosteroids therapy between the death and the surviving groups (p=0.44). The medians of time duration of corticosteroids therapy were 3 days either in the death group or in the surviving group showing no significant difference between them (p=0.55).

Discussion

Since the first case with p(H1N1) infection was reported on 19 June 2009 in Anhui province, China, a total of 126 severe cases of p(H1N1) had been reported till 30 April 2010, including 46 (37%) pregnant cases. And the case–death rate of pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection was around 15%, which was 4% higher than the mortality of the severe cases of p(H1N1). Pregnant women were considered to be at the highest risk group during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.12

Compared with the non-pregnant cases, the pregnant cases were more likely to develop complications, such as pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). As for the pregnant cases, the decreasing adjuvanticity T cells and the falling activity of NK cell can result in compromising the immune response system. Furthermore, the increscent womb and uplifted diaphragm can weaken the capacity of cleaning the secretion of respiratory track and decrease the lung's remaining air as well. Nevertheless, the pregnant women need more oxygen, but their lungs are filled with more liquid. All these could cause the pregnant cases more susceptible to complication. In addition, the severity and the time course of pneumonia occurred in the pregnant cases were nine times more than and three times longer than the non-pregnant cases.13

In the southern China, the influenza epidemic season starts from December to March of next year. Severe cases of p(H1N1) were reported in October 2009 and peaked on December 2009 in Anhui province.

When pandemic influenza A(H1N1) occurred, the Health Ministry of China responded to it quickly and formulated the emergency vaccination plan. The highest risk people in Anhui province had been vaccinated since the end of October 2009. So people could have obtained enhanced immune system to p(H1N1) virus through vaccine or the antibody level set up in natural infection.14 This maybe accounts for the less cases reported after December 2009. Vaccination during pregnancy is not contraindicated and therefore can be considered.15

Of 46 pregnant patients, 35 (76%) were in their third trimester. Among the seven pregnant women who died of the p(H1N1) infection, five (70%) cases were in their third trimester. So the third trimester was at the highest risk time period for the pregnant women to p(H1N1) infection or suffer from more severe outcomes. This is consistent with the observation of influenza-associated with excess deaths among pregnant women during the previous pandemics, with risk increasing with advancing stages of pregnancy.16

In the third trimester, the rapidly developing fetus overburdens its mother consuming more oxygen. In addition, pregnant women in the third trimester were more concerned on having x-ray tests so there are possibility of misdiagnosing them.13 Consequently, the pregnant women in the third trimester probably face the higher risk than the first two trimesters.

In the death group, the median of the time interval from onset to death was 18 days. In the surviving group, the time duration from onset to recovery varied from 5 to 39 days and the median was 14 days. It shows that if the pregnant women with severe infection of pandemic H1N1 cannot be cured after 2-week treatment, we need to pay much more attention to preventing them from dying in the next several days.

The pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection showed no significant difference in age between the death group and the surviving group and the median age in two groups was 21 years. However, in the review of a large number of hospitalised and fatal cases of pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in California, the median age was 27 years.17 The difference of median age between Anhui and California probably needs to be studied further.

The pregnant women in the surviving group were admitted to hospital significantly earlier than the death group, showing an early admission was critical for the severe pregnant cases to reduce the possibility of death. During our investigation, we asked the cases or their family members the reasons of the pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection to delay their admission to hospital and knew several possible reasons, which are as follows: first, they were afraid that they would more likely be exposed to the respiratory infectious diseases by close contacts with the patients while visiting a doctor of respiratory medicine. Second, they were concerned with the possible side effects on their baby while taking some Western medicine so they would rather seek help from a local Chinese traditional medicine expert. Lastly, they presented the influenza-like symptoms resembling the common cold so they did not think that it was really necessary to seek medical care immediately.

In this study, the pregnant cases who finally recovered from the severe p(H1N1) infection were given the antiviral drugs earlier than the pregnant cases who died, but there was no significant difference in the time duration of treatment. Probably, to give antiviral treatment as soon as possible was critical to prevent the pregnant cases from death. This is in accordance with the previous studies showing that antiviral therapy is the most beneficial when treatment is initiated within 48 h after the onset of illness.18 However, according to our results, a time course of antiviral treatment was enough and there was no need to extend the extra time of treatment. Considering the limitations of our report, this should be further studied to confirm it.

In terms of corticosteroids therapy, no significant difference was seen between the death group and the surviving group either in how soon or how long to use it so may be it is unnecessary to be chosen for treating the pregnant cases with severe p(H1N1) infection. Additionally, in the concerns of the side effect of corticosteroids on the human health—compromising the immune system—the corticosteroids treatment probably should not be recommended to the severe pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection for shrinking the possibility of death.

Limitations

Our estimates may not be generalised to the rest of the severe pregnant cases infected by pandemic H1N1 as the relatively small sample limited the ability of extrapolation. Also, the severe pregnant women who did not undergo routine prenatal screening or who visited the other hospitals that were not our sentinel hospitals were not represented. Additionally, comorbidity records were not generally available, particularly for fatal cases.

Conclusions

For the pregnant cases with severe p(H1N1) infection, the risk factors associated with death were as follows: the delayed use of antiviral drug and being in the third trimester. The corticosteroids use appeared to have no effect on preventing the severe pregnant cases from dying. And, vaccination is an effective measure to prevent the pregnant women from getting p(H1N1) infection.

This article adds confirmatory data to that reported in previous studies,19 20 which suggests that early admission and antiviral drug treatment are to be recommended and that more than one course of antiviral treatment and corticosteroids might be unhelpful in reducing the possibility of a fatal outcome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following institutions that allowed access, analysis and reporting of the survey data: Xuancheng City CDC, Huangshan City CDC, Ma Anshan City CDC, Wuhu City CDC, Hefei City CDC, Tongling City CDC, Bengbu City CDC, Huainan City CDC, Anqing City CDC, Suzhou City CDC, Fuyang City CDC, Bozhou City CDC, Chuzhou City CDC, Huaibei City CDC, Lu'anCity CDC, Chizhou City CDC. The authors also thank Lauren Boettler for correcting errors of English expression. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the above-mentioned institutions.

Footnotes

To cite: Li F, Chen G, Wang J, et al. A case–control study on risk factors associated with death in pregnant women with severe pandemic H1N1 infection. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000827. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000827

Contributors: FL and JWa designed the case–control study on the pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection. GC performed the statistical analysis. FL, GC, JWu and HL interpreted and drafted the manuscript. JWa and HL revised critically for some important contents. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by China-WHO Influenza Surveillance Cooperative Project.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This research did not get involved in any clinical trial. The cases were tested just for confirming their diagnosis and received the regular treatment. We just did the questionnaire investigation of the cases after they consented. So there are no ethics issues.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No further data are available.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infections in three pregnant women — United States, April–May 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:497–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009;58:1–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman DW, Barno A. Deaths from Asian influenza associated with pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1959;78:1172–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris JW. Influenza occurring in pregnant women. JAMA 1919;72:978–80 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet 2009;374:451–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Bresee JS. Pandemic influenza and pregnant women. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:95–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saleeby E, Chapman J, Morse J, et al. H1N1 influenza in pregnancy: cause for concern. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:885–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minerva CG, Odile L. Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in pregnant women: impact of early diagnosis and antiviral treatment. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;111:217–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The ANZIC Influenza Investigators and Australasian Maternity Outcomes Surveillance System Critical illness due to 2009 A/H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women: population based cohort study. BMJ 2010;340:c1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sara FG, Leyla S, Beverly G. Enrolling pregnant women in research-lessons from the H1N1 influenza pandemic. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2241–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang SG, Cao B, Liang LR, et al. Antiviral therapy and outcomes of patients with pneumonia caused by influenza A pandemic(H1N1) Virus. PLoS One 2012;7:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, et al. ; Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus investigation Team Emergence of a Novel Swine-Origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in Humans. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2605–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao Y, Wang W, Wang J, et al. Clinical analysis of 9 severe pregnant women with p(H1N1) infection. Chin J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;9:234–8 [Google Scholar]

- 14.http://ah.anhuinews.com/system/2009/10/31/002379545.shtml

- 15.Santiago EZ, Juan MM, Alvaro JM, et al. Infection and death from influenza A H1N1 virus in Mexico: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2009;374:2072–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet 2009;374:451–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janice KL, Meileen A, Kathleen W, et al. Factors associated with death or hospitalization due to Pandemic 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) Infection in California. JAMA 2009;302:1896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Updated interim recommendations for the use of antiviral medications in the treatment and prevention of influenza for the 2009-2010 season Atlanta. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/recommendations.htm (accessed 19 Oct 2009).

- 19.Alicia MS, Sonja AR, Margaret AH, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA 2010;303:1517–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seth JS, Robert MJ, Walter RD, et al. 2009 H1N1 influenza. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:64–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.