Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the evidence regarding long-term prophylaxis in the prevention or reduction of attacks in hereditary angio-oedema (HAE).

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Electronic databases were searched up to April 2011. Two reviewers selected the studies and extracted the study data, patient characteristics and outcomes of interest.

Eligibility criteria for selected studies

Controlled trials for HAE prophylaxis.

Results

7 studies were included, for a total of 73 patients and 587 HAE attacks. Due to the paucity of studies, a meta-analysis was not possible. Since two studies did not report the number of HAE attacks, five studies (52 patients) were finally included in the summary analysis. Four classes of drugs with at least one controlled trial have been proposed for HAE prophylaxis. All those drugs, except heparin, were found to be more effective than placebo. In the absence of direct comparisons, the relative efficacies of these drugs were determined by calculating a RR of attacks (drug vs placebo). The results were as follows: danazol (RR=0.023, 95% CI 0.003 to 0.162), methyltestosterone (RR=0.054, 95% CI 0.013 to 0.163), ɛ-aminocaproic acid (RR=0.095, 95% CI 0.025 to 0.356), tranexamic acid (RR=0.308, 95% CI 0.195 to 0.479) and C1-INH 0.491 (95% CI 0.395 to 0.607).

Conclusions

Few trials have evaluated the benefits of HAE prophylaxis, and all drugs but heparin seem to be effective in this setting. Since there are no direct comparisons of HAE drugs, it was not possible to draw definitive conclusions on the most effective one. Thus, to accumulate evidence for HAE prophylaxis, further studies are needed that consider the dose–efficacy relationship and include a head-to-head comparison between drugs, with the active group, rather than placebo, as the control.

Article summary

Article focus

To find evidence regarding long-term prophylaxis in the prevention or reduction of attacks in HAE.

Key messages

Four classes of drugs have been proposed for HAE prophylaxis: androgen derivatives, antifibrinolytics, C1-inhibitor and heparin.

All, except heparin, have been shown to be more effective than placebo.

To accumulate evidence supporting HAE prophylaxis, further studies, including head-to-head comparisons between drugs, are needed, with the active group rather than placebo as the control.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first systematic review on this topic.

Only seven studies were retrieved, for a total of 73 patients and 587 HAE attacks; there were no direct comparisons between drugs.

It was not possible to draw definitive conclusions on the most effective drug.

Introduction

Hereditary angio-oedema (HAE) is a rare genetic disorder resulting from an inherited deficiency or dysfunction of C1 inhibitor (C1-INH). It is characterised by recurrent episodes of angio-oedema, without urticaria or pruritus, and primarily affects the skin or the mucosal tissues of the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. The inheritance of HAE is autosomal dominant, but only a few affected individuals are homozygous for the defect.1 The prevalence of the disease in the general population is estimated at one individual per 50 000, with reported ranges from 1:10 000 to 1:150 000 and no racial differences.2–5 The two most common forms of HAE (types I and II) result from either a deficiency or a dysfunction of C1-INH. In the former, antigenic and functional levels of C1-INH are below 50% of normal, while in the latter (ie, in type II), antigenic levels are normal to elevated, but function is low.6 7 Nearly 90% of patients suffer from both cutaneous and abdominal attacks, while 50% also experience laryngeal/pharyngeal oedema.8–10 Attacks typically involve one site at a time, but the simultaneous involvement of multiple sites is not common.10 Symptoms usually increase in severity over a period of 24 h and then subside over the next 24–72 h. The frequency of recurrences has an extremely high intrasubject and intersubject variability, ranging from less than once a year up to every 3–4 days.11 Laryngeal recurrences are less common, accounting for 6% of all angio-oedema episodes.12 The socioeconomic consequences of HAE are significant, as patients with frequent attacks may miss up to 100–150 days of work each year.10

Although HAE-induced swelling is self-limited, laryngeal involvement may cause asphyxiation. In fact, the mortality rate of patients not properly diagnosed or treated is reportedly as high as 30%. In addition to the risk of death, the burden of the disease is related to the symptom-derived disability, which, in turn, is a function of the frequency and severity of the attacks.

Two therapeutic strategies can ameliorate this burden: (1) prophylactic therapy, aimed at reducing the number of attacks, and (2) treatment of the attacks to reduce their severity and duration. Their common end point is a reduction of the duration of angio-oedema-related disability and the risk of asphyxiation induced by laryngeal oedema.

The controlled studies of HAE carried out thus far were designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of single drugs; none compared either the different drugs or the different therapeutic approaches (eg, prophylaxis vs treatment of attacks). To the best of our knowledge, there are no meta-analyses of these studies. Hence, existing consensus documents support treatment recommendations primarily based on expert opinion rather than on a systematic review of the evidence.4 Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically review the evidence regarding the efficacy of HAE long-term prophylaxis.

Methods

Data sources

Relevant primary studies were identified by searching the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases, the Cochrane Library and the http://Clinicaltrials.gov database (to identify ongoing trials yet to be reported in the literature) until April 2011. Both the reference lists included in the clinical guidelines and the proceedings of relevant meetings were also considered. The search strategy was based on the target disease (hereditary angioedema, C1 inhibitor and synonyms) and the type of study (controlled trial and synonyms according to the Cochrane collaboration guidelines). No language restrictions were applied.

Eligible studies were controlled trials evaluating long-term prophylactic therapies for HAE.

All the evaluated studies were included if they had a placebo or comparison group. Cross-over and parallel group designs were also included.

Observational studies, single-arm studies and studies with historical controls were excluded.

Two reviewers (GCo and IB) independently screened titles and abstracts to identify relevant publications. Full texts were retrieved and evaluated by the same two reviewers (GCo and IB), and a final decision regarding the inclusion or exclusion of the paper was made. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion; in case of disagreement, the final decision was made by a clinical expert (MC).

Data extraction

Two reviewers (IB and GCo) extracted the data, which were recorded in an electronic spreadsheet. Extracted data consisted of the study characteristics (first author, journal and year of publication, drug name, number of patients enrolled/included, primary end point with its statistical significance, study duration), some of the patient characteristics (mean age, proportion of men) and the outcome of interest.

Quality assessment of primary studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed based on the five-item Jadad score, which takes into account several of the methodological characteristics of clinical studies, such as blinding, randomisation and dropouts.13 Studies with a score <3 were considered of low quality.

Outcome of interest

The outcome of interest was the number of HAE attacks during prophylaxis treatment. In this study, two different end points were considered: the number of attacks per course of therapy and the number of attacks per month. Studies without at least one of these end points were not considered in the analysis.

Data analysis

For each included study in which the data were reported as number of courses with and without attacks, the attack rate was calculated by dividing the number of HAE attacks by the total number of courses of treatment. For studies in which the data were reported as the number of attacks and the number of months of treatment, the attack rate was defined as the ratio between the number of HAE attacks and the total number of months of treatment. The attack rate was calculated separately for the drug and the control groups. To obtain a summary measure of efficacy for use in the analysis, a RR with 95% CI was calculated as the ratio of the attack rates in the drug and control groups.14

Pooled RRs with their 95% CIs for the same type of drug were calculated, when appropriate, using a random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method) for RRs.15 Graphical representation of the study results was obtained by plotting RR estimates with their 95% CIs in a Forest plot.

In the absence of a direct comparison, an indirect comparison (for descriptive purposes) between drugs was done simply by comparing the estimates (95% CIs) of those drugs.16 All the analyses were performed with STATA software, release V.11.0.

Results

Descriptive analysis

From the 11 412 references identified by the search strategy, 11 344 were excluded after title/abstract review. Of the remaining 68 references, 61 were excluded after a full-text evaluation: 43 articles reported studies that were not trials, four studies were duplicate publications, three studies had no end point, one article was a trial with retrospective controls and the focus of 10 studies was on therapy only, not on prophylaxis. Thus, seven studies were eligible for descriptive analysis (figure 1). The total number of patients enrolled in the seven studies was 73 (range 4–22). The efficacy evaluation was based on HAE attack recurrences, with 587 recurrences registered by the studies. Two of the seven studies17 18 did not report the number of attacks; thus five studies (52 patients) were considered for the analysis.19–23

Figure 1.

Search history.

All the studies were designed to evaluate the efficacy of a single dose of a specific drug. The main characteristics of the included studies are summarised in table 1. The first study was published in 1972 and the last one in 2010. All were cross-over designed and the control group was placebo. In all but one study,17 a statistically significant result was achieved for the primary end point. Three different classes of drugs were evaluated: antifibrinolytics (one study with ɛ-aminocaproic acid and one with tranexamic acid), androgen derivatives (one study with danazol and one with methyltestosterone), plasma-derived C1-INH (one study with a vapour-heated preparation and one with a pasteurised, nanofiltered preparation) and heparin (one study). The duration of treatment ranged from a minimum of 1 month to a maximum of 16 months. No major side effects were reported in any of the studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| First author | Drug | Dose | Number of patients included | Mean age (years) | Minimum number attacks for month | Mean attacks for month controls | Primary end point | Randomised | Jadad score |

| Frank (1972)19 | Aminocaproic acid | 16 g/day | 5 | 35.6 | 1 | – | No. of courses with and without attacks in drug and placebo | No | 4 |

| Sheffer (1972)20 | Tranexamic acid | 3 g/day | 12 | 12–72 | – | 1.1 | No. of attacks for month | No | 1 |

| Gelfand (1976)21 | Danazol | 600 mg/day | 9 | 34.9 | 1 | – | No. of courses with and without attacks in drug and placebo | Yes | 5 |

| Sheffer (1977)22 | Methyltestosterone | 10 mg/day | 4 | – | 1 | 1.6 | No. of attacks for month | Yes | 3 |

| Weiler (2002)17 | Heparin | 400 U/kg/day | 15 | 32.6 | 1 | – | Average flare intensity | Yes | 5 |

| Waytes (1996)18 | V-H C1 inhibitor | 25 plasma unit/kg/every 3 days | 6 | – | 0.5 | – | Daily score for disease activity | Yes | 5 |

| Zuraw (2010)23 | C1 inhibitor | 1000 U/every 3–4 days | 22 | 38.1 | 2 | 4.24 | No. of attacks normalised for the number of days | Yes | 5 |

V-H, Vapour-heated.

Primary efficacy end points, against placebo, were the number of courses (a course terminated whenever an attack occurred or after 1 month) with and without attacks (two studies), the number of attacks per month (two studies), the average flare intensity (one study), the daily score of disease activity (one study) and the number of attacks normalised for the number of days (one study).

According to the Jadad score, six out of the seven trials were high-quality studies (Jadad score range: 1–5).

Summary of the results

Due to the paucity of studies retrieved and to the substantial heterogeneity between them (study design, definition of end points), it was not appropriate to perform any meta-analyses.

For the studies considered in the analysis, the number of enrolled patients, the end points and the frequency of attacks in the treatment and control groups are summarised in table 2 and figure 2.

Table 2.

Summary of results of the included studies

| Drug | No. of patients | Treatment |

Control |

RR treatment/control (95% CI) | ||

| No. of attacks/No. of courses | Ratio | No. of attacks/No. of courses | Ratio | |||

| Studies considering number of attacks per therapeutic course | ||||||

| Aminocaproic acid19 | 5 | 2/21 | 0.10 | 24/24 | 1.00 | 0.095 (0.025 to 0.356) |

| Danazol21 | 9 | 1/46 | 0.02 | 44/47 | 0.94 | 0.023 (0.003 to 0.162) |

| Drug | No. of patients | Treatment | Control | RR treatment/control (95% CI) | ||

| No. of attacks/No. of months | Ratio | No. of attacks/No. of months | Ratio | |||

| Studies considering number of attacks per months | ||||||

| Tranexamic acid20 | 12 | 32/94 | 0.34 | 63/57 | 1.11 | 0.308 (0.195 to 0.479) |

| Methyltestosterone22 | 4 | 4/46 | 0.09 | 19/12 | 1.61 | 0.054 (0.013 to 0.163) |

| C1 inhibitor23 * | 22 | 131/63 | 2.07 | 267/63 | 4.24 | 0.491 (0.395 to 0.607) |

Number of attacks (expressed as attacks per month) was derived from the attack rate (expressed as attacks per 12 weeks) as reported in the study.

Figure 2.

RR of drugs analysed compared with placebo.

Antifibrinolytics. Two antifibrinolytics were analysed in two separate studies (17 patients, 121 HAE attacks), with both drugs shown to be better than placebo. The estimates of RR differed greatly between studies (figure 2).

Androgens. Two studies compared androgen derivatives with placebo in 13 patients who registered five and 63 attacks, respectively. In both studies, the drugs were more effective than placebo and the RR values of the two studies were similar (figure 2).

C1-inhibitor. Data were available for only one study, which reported that in 22 patients C1-INH and placebo had an average period-specific normalised attack rate of 6.26 and 12.73, respectively. The estimated RR was 0.491 (95% CI 0.395 to 0.607).

Heparin. The only data provided by the one study were those for flare intensity, which did not significantly differ between active and control groups. While no data were published on the number of attacks, the authors did state that these numbers were not significantly different between the drug and the placebo groups.

Indirect comparison. In the absence of head-to-head comparisons and due to the very limited number of studies, the differences between the drugs were estimated in informal descriptive comparisons.

Based on the studies in which the number of attacks and the number of courses of treatment with drug or placebo were the primary end points, danazol (RR=0.023, 95% CI 0.003 to 0.162) seemed to be comparable to ɛ-aminocaproic acid (RR=0.095, 95% CI 0.025 to 0.356). In the studies that reported the number of attacks per month, methyltestosterone (RR=0.054, 95% CI 0.013 to 0.163) seemed to be better than tranexamic acid (RR=0.308, 95% CI 0.195 to 0.479). Finally, an indirect comparison between all treatments involving drugs of the same pharmacological class and not separated for end point suggested that androgen derivatives are more effective than C1-INH, while the efficacy of antifibrinolytics is midway between that of androgens and C1-INH.

Heterogeneity. As clearly seen in the Forest plot (figure 2), the point estimates of each study were very imprecise, with wide-ranging variability between the primary studies.

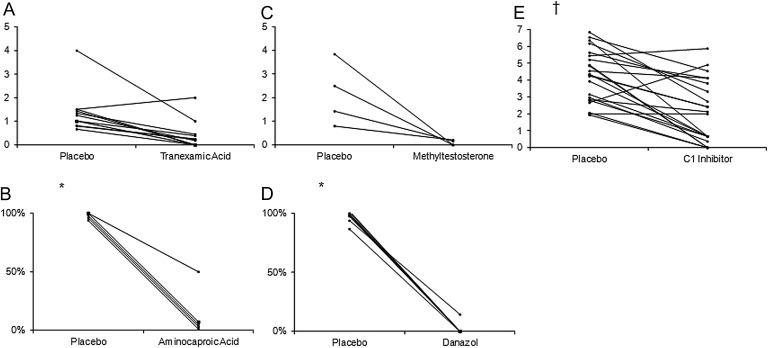

Figure 3 allows a quick visual comparison, for every study, of the number of attacks experienced by each patient during courses of treatment with placebo or with active drug. A reduction in the frequency of attacks was achieved during active treatment in all but four patients: one on tranexamic acid and three on C1-INH.

Figure 3.

(A) Single patient data of placebo versus tranexamic acid study (attacks per months); (B) single patient data of placebo versus aminocaproic acid study (cycle of therapy with attacks vs total number of cycles); (C) single patient data of placebo versus methyltestosterone study (attacks per months); (D) single patient data of placebo versus danazol study (cycle of therapy with attacks vs total number of cycles); (E) single patients data of placebo versus C1 inhibitor study (attacks per months). For explanation, see text. *For graphical purposes, some patients' values have been slightly modified. †Data retrieved from figure 2 of the original paper.

Discussion

This systematic review identified four classes of drugs used for HAE prophylaxis: androgen derivatives, antifibrinolytics, heparin and C1-INH. The drugs were tested in at least one controlled trial and, with the exception of heparin, all of them were shown to be better than placebo in reducing the frequency of attacks. The small number of patients in each trial explains the low precision of the estimates of RR (see figure 2), which, in turn, were at least partly responsible for the observed variability of the RRs between studies. As seen in figure 2, the RR point estimates are quite different, but almost all the 95% CIs overlap, indicating high interstudy and intrastudy variability. The observed heterogeneity could be due to several factors, the most important of which may have been the fact that five different primary end points were considered across the seven primary studies. Moreover, the year of publication ranged from 1972 to 2010. During this interval, there have been many changes in the diagnosis and management of HAE. The inclusion criteria also varied from study to study, but even when they were similar, as for average attack frequency, the respective placebo groups still behaved differently. The mean number of attacks for the placebo group was higher in the C1-INH study23 than in the other (four vs two attacks per month, respectively). This suggests that disease severity differed in the patients recruited for the examined studies. Finally, the large variability in follow-up duration (from 1 month to 16 months) is another relevant important difference that no doubt contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

All trials considered for this analysis were published in core medical journals, reflecting the high clinical interest in HAE. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the studies on androgens and antifibrinolytics were conducted in the 1970s. While no serious side effects were reported in the included trials, randomised clinical trials are not the best study design to investigate side effects, particularly for long-term treatments. Indeed, extensive clinical experience has since accumulated with attenuated androgens and antifibrinolytics, and side effects are well known from observational studies.3 C1-INH, used for 30 years in the treatment of attacks, was only recently recognised as indicated for prophylaxis. A close look at the early trials from the vantage point of current clinical experience reveals important side effects of androgens used at doses of 600 mg/day, as was the case in those clinical trials. Over time, clinical practice has shown that much lower doses maintain clinical efficacy and with fewer side effects, allowing treatment to be continued over the very long term.24 25 Nevertheless, the level of efficacy at these lower doses has never been quantified in a controlled study. In addition, while the efficacy of antifibrinolytics in long-term prophylaxis was confirmed, clinical experience showed that there are no doses that can lead a large number of patients to have significant benefit. Thus, today, only a small minority of patients with HAE continue to use these drugs. In fact, according to the most recently released consensus document on HAE treatment, antifibrinolytics are not considered as a relevant agent.26 Although we do not have large documented clinical experience with C1-INH, the available data suggest the importance of individually titrating effective doses in order to establish the ‘minimal effective dose’; this is current practice with danazol.27 28 The problem of effective dose has never been addressed in clinical trials. This is a major limitation particularly for prophylactic treatments in which the risk–benefit balance is crucial as the relevant drug is likely to be taken life-long. Increasing awareness of HAE can be expected to focus on this issue, but its resolution will require long-ranging clinical experience.

One of the aims of our systematic review was to compare therapies, which could only be done indirectly. However, we were unable to single out a superior therapy due to the small number of patients enrolled in the studies and the broad CIs of the point estimates. Indeed, an indirect comparison of the studies considering the same end point showed that while methyltestosterone seems to be more effective than tranexamic acid, danazol does not differ from ɛ-aminocaproic acid.19–22 For a more specific comparison of the different trials, the response of each patient in each trial, both in the placebo group and in the active group, was analysed (figure 3). The results showed that all 13 patients treated with androgens had a marked reduction in the number of attacks, suggesting a uniform efficacy of this drug among patients. By contrast, a reduction was not achieved by one of 17 patients in the antifibrinolytic group and three of 22 patients in the C1-INH group. A first and obvious explanation of these differences is the extremely small number of patients included in some of the studies, such that the variability of the HAE population could not be adequately determined. Another possibility, already highlighted, is that in the absence of convincing dose-finding studies, the respective drugs may have been overdosed or underdosed.

Limitations

The major limitation of our systematic review was the very small number of patients enrolled in the original studies and the heterogeneity between the studies considered. Moreover, there was no consensus on the definition of the primary end point, as in some studies it was the number of courses with and without attacks, and in others, it was the number of attacks per month or the average flare intensity.

Given the paucity of studies published in the literature, to obtain useful evidence we opted to compare results from different studies, irrespective of the heterogeneity arising from differences in the designs of the primary studies (ie, definition of primary end point, drugs considered).

Another limitation is related to the statistical analysis. In each original study, we considered the number of months (or courses) and the number of attacks in both the placebo and the active group as if they were independent. Since all were cross-over trials, with this analyses, the correlation within patients is ignored.

In conclusion, our systematic review supports the use of certain drugs in the prophylaxis of attacks in patients with HAE, but we were unable to determine whether one prophylactic therapy is better than another. Clearly, there is a compelling need for more trials, with head-to-head comparisons, to provide convincing evidence of the benefit and safety of a specific, potentially life-long prophylactic regimen.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Costantino G, Casazza G, Bossi I, et al. Long-term prophylaxis in hereditary angio-oedema: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000524. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000524

Contributors: GCo, GCa, PD and MC designed the study. GCa and PD wrote the statistical analysis plan and analysed the data. GCo and IB screened titles and abstracts to identify relevant publications and extracted the data. All authors participated in drafting the paper and in its subsequent revision.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from Telethon (No. GGP08223).

Competing interests: MC has a consultancy agreement and/or has been an invited speaker for the following companies that produce treatments for hereditary angio-oedema: CSL Behring, Shire, Dyax, Viro Pharma, Pharming. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Blanch A, Roche O, Urrutia I, et al. First case of homozygous C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118:1330–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez-Lera A, Favier B, Mena de la Cruz B, et al. A new case of homozygous C1-inhibitor deficiency suggests a role for Arg378 in the control of kinin pathway activation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:1307–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roche O, Blanch A, Caballero T, et al. Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency: patient registry and approach to the prevalence in Spain. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005;94:498–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen T, Cicardi M, Farkas H, et al. 2010 International consensus algorithm for the diagnosis, therapy and management of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2010;6:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bygum A. Hereditary angio-oedema in Denmark: a nationwide survey. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:1153–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tosi M. Molecular genetics of C1 inhibitor. Immunobiology 1998;199:358–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prada AE, Zahedi K, Davis AE., 3rd Regulation of C1 inhibitor synthesis. Immunobiology 1998;199:377–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, et al. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med 2006;119:267–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bork K, Staubach P, Eckardt AJ, et al. Symptoms, course, and complications of abdominal attacks in hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:619–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostoni A, Cicardi M. Hereditary and acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency: biological and clinical characteristics in 235 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1992;71:206–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gompels MM, Lock RJ, Abinun M, et al. C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus document. Clin Exp Immunol 2005;139:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanichelli A, Vacchini R, Badini M, et al. Standard care impact on angioedema because of hereditary C1 inhibitor deficiency: a 21-month prospective study in a cohort of 103 patients. Allergy 2011;66:192–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman & Hall, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context. London: BMJ Books, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, et al. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiler JM, Quinn SA, Woodworth GG, et al. Does heparin prophylaxis prevent exacerbations of hereditary angioedema? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;109:995–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waytes AT, Rosen FS, Frank MM. Treatment of hereditary angioedema with a vapor-heated C1 inhibitor concentrate. NEJM 1996;334:1630–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank MM, Sergent JS, Kane MA, et al. Epsilon aminocaproic acid therapy of hereditary angioneurotic edema. A double-blind study. NEJM 1972;286:808–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheffer AL, Austen KF, Rosen FS. Tranexamic acid therapy in hereditary angioneurotic edema. NEJM 1972;287:452–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelfand JA, Sherins RJ, Alling DW, et al. Treatment of hereditary angioedema with danazol. Reversal of clinical and biochemical abnormalities. NEJM 1976;295:1444–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheffer AL, Fearon DT, Austen KF. Methyltestosterone therapy in hereditary angioedema. Ann Intern Med 1977;86:306–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. NEJM 2010;363:513–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloane DE, Lee CW, Sheffer AL. Hereditary angioedema: safety of long-term stanozolol therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:654–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bork K, Bygum A, Hardt J. Benefits and risks of danazol in hereditary angioedema: a long-term survey of 118 patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;100:153–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicardi M, Bork K, Caballero T, et al. ; HAWK (Hereditary Angioedema International Working Group) Evidence-based recommendations for the therapeutic management of angioedema owing to hereditary C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus report of an International Working Group. Allergy 2012;67:147–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreuz W, Martinez-Saguer I, Aygören-Pürsün E, et al. C1-inhibitor concentrate for individual replacement therapy in patients with severe hereditary angioedema refractory to danazol prophylaxis. Transfusion 2009;49:1987–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agostoni A, Cicardi M, Martignoni GC, et al. Danazol and stanozolol in long-term prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1980;65:75–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.