Abstract

Telaprevir, a novel hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3-4A serine protease inhibitor, has demonstrated substantial antiviral activity in patients infected with HCV. However, drug-resistant HCV variants were detected in vivo at relatively high frequency a few days after drug administration. Here we use a two-strain mathematical model to explain the rapid emergence of drug resistance in HCV patients treated with telaprevir monotherapy. We examine the effects of backward mutation and liver cell proliferation on the preexistence of the mutant virus and the competition between wild-type and drug-resistant virus during therapy. We also extend the two-strain model to a general model with multiple viral strains. Mutations during therapy only have a minor effect on the dynamics of various viral strains, although they are capable of generating low levels of HCV variants that would otherwise be completely suppressed because of fitness disadvantages. Liver cell proliferation may not affect the pretreatment frequency of mutant variants, but is able to influence the quasispecies dynamics during therapy. It is the relative fitness of each mutant strain compared with wild-type that determines which strain(s) will dominate the virus population. This study provides a theoretical framework for exploring the prevalence of preexisting mutant variants and the evolution of drug resistance during treatment with other HCV protease inhibitors or polymerase inhibitors.

Keywords: Telaprevir, mutation, fitness, quasispecies, direct-acting antiviral agents, mathematical model

1 Introduction

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) has caused an epidemic with approximately 130 to 170 million people infected worldwide and 3 to 4 million individuals newly infected each year [1]. About 80% of newly infected patients develop chronic infection. Of those chronically infected, 60 – 70% develop chronic liver disease, 5 – 20% develop cirrhosis, and 1 – 5% die from cirrhosis or liver cancer [1]. A combination of pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN), administered once weekly, and daily oral ribavirin (RBV) has been used to treat HCV infection for 24 or 48 weeks [2]. Although the combination exerts synergistic antiviral effects [3, 4], it leads to sustained viral elimination in only some treated patients. The HCV genotype appears to be an important factor in predicting response. In patients infected with genotypes 2 and 3, about 80–90% of patients achieve a sustained viral response (SVR), defined as the absence of detectable serum HCV RNA 24 weeks after completion of treatment. In patients infected with genotype 1, the major genotype affecting North America, Europe and Japan, only about 40% of treated individuals achieve SVR [2]. Lack of a complete response, viral relapse following treatment, and premature termination of therapy due to adverse events that occur during dosing all contribute to this unsatisfactory response rate observed among HCV genotype 1 infected patients. Therefore, new antiviral drugs with higher efficacy, shorter treatment duration, and a more favorable side-effect profile as a monotherapy or in combination with other antivirals are highly desirable.

New treatment options are focused on the development of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) that target different steps of the HCV life cycle [5–7]. An important target is the HCV-encoded NS3-4A serine protease. In clinical trials HCV protease inhibitors have been used to treat HCV genotype 1 infected patients. They have shown an impressive capacity to block the NS3-4A protease-dependent cleavage of the HCV polyprotein, which is an essential step in viral replication (HCV replication will be discussed in detail later). The first protease inhibitor, BILN 2061 (ciluprevir; Boehringer-Ingelheim), showed potent antiviral activity in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 [8], but clinical development was halted due to drug-induced cardiotoxicity [9]. Boceprevir (SCH 503034; Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals), another oral HCV protease inhibitor, also demonstrated substantial antiviral effects when used in combination with PEG-IFN-alpha-2b in HCV genotype 1 infected patients, who were previously nonresponders to PEG-IFN-alpha-2b with/without RBV therapy [10]. Telaprevir (VX-950; Vertex Pharmaceuticals) is a reversible, selective, and specific peptidomimetic inhibitor of NS3-4A that is effective in inhibiting viral replication in HCV replicon cells [11]. It had a favorable pharmacokinetic profile with high exposure in the liver in several animal models [12], and in monotherapy induced a profound decline of plasma HCV RNA levels of the order of 3–4 logs in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 treated for 14 days [13]. Both boceprevir and telaprevir have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat HCV infection when used in combination with PEG-IFN and RBV. The addition of either of them to therapy with PEG-IFN and RBV has significantly increased the rates of SVR [14–18].

Emergence of drug-resistant mutations is a problem challenging the development of direct-acting antiviral drugs. Like most RNA viruses, HCV evolves rapidly because of high-level viral replication through an error-prone RNA polymerase that lacks associated proofreading capacity. As a consequence, the viral population exists as a complex mixture of genetically distinct, but closely related, variants commonly referred to as a quasispecies, whose composition is subject to continuous change due to the competition between newly generated mutants and existing variants with different phenotypes and fitness [19]. During antiviral therapy pre-existing minor viral populations with reduced susceptibility to the administered drug or drugs will gain a growth advantage over wild-type and become the dominant genotype. The amino acid substitutions selected by protease inhibitors that confer drug resistance have been characterized in vitro in the HCV replicon system [20–22].

The initial selection and kinetics of telaprevir-resistant HCV variants have been further described in patients given the protease inhibitor alone [13, 23] or in combination with PEG-IFN-alpha-2a [24, 25]. Although 14 days of treatment resulted in substantial decreases in HCV RNA levels, there was evidence of viral breakthrough in some patients during the dosing period, which was believed to be associated with the selection of HCV variants with reduced sensitivity to telaprevir [13]. Using a highly sensitive sequencing assay, Sarrazin et al. [23] identified mutations that confer resistance to telaprevir in the NS3 protease catalytic domain and correlated them with virologic response. These mutations were further investigated in a subsequent study [25] that provides a detailed kinetic analysis of HCV variants in patients treated with telaprevir alone or in combination with PEG-IFN-alpha-2a for 14 days. The four HCV genotype 1a infected patients in the telaprevir monotherapy group all exhibited viral load rebound during the dosing period. Virus isolated from these patients at day 2 contained low levels (5%–20%) of single-mutant resistant variants, which increased in the population of virus isolated at days 6 and 10, and were replaced by more resistant double-mutant variants by day 13 and during the first follow-up week with PEG-IFN plus RBV [25]. Why drug-resistant viral variants emerged so rapidly following treatment with telaprevir is not fully understood.

In this paper, we study HCV quasispecies and drug resistance in patients treated with the protease inhibitor telaprevir. We begin with a simple two-strain model in which liver cells, e.g., hepatocytes, infected with wild-type virus are able to produce not only wild-type virus but also a small amount of drug-resistant variants. The two-strain model was studied numerically and was shown to fit the observed dynamics of both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant viruses in patients treated with telaprevir [26]. Here we study this model analytically. With reasonable simplifications, we obtain an analytical solution for the mutant frequency in patients given telaprevir alone, which is capable of explaining the rapid selection of pre-existing drug resistant variants after therapy initiation. We study the competition between wild-type and drug-resistant virus during treatment. We also examine the effects of backward mutation and hepatocyte proliferation on the pre-existing mutant frequency and the evolution of viral variants during therapy. Extending the two-strain model, we then develop a multi-strain model in which drug-resistant HCV variants that differ at more than one site are incorporated. We calculate the expected frequency of each viral strain in untreated patients. The results of the competition between multiple viral variants during therapy with telaprevir are also provided. Because telaprevir and boceprevir inhibit the same HCV protease, the analysis in this study with telaprevir can be applied to boceprevir or to other HCV protease inhibitors under development.

2 Rapid emergence of drug resistance

2.1 Model description

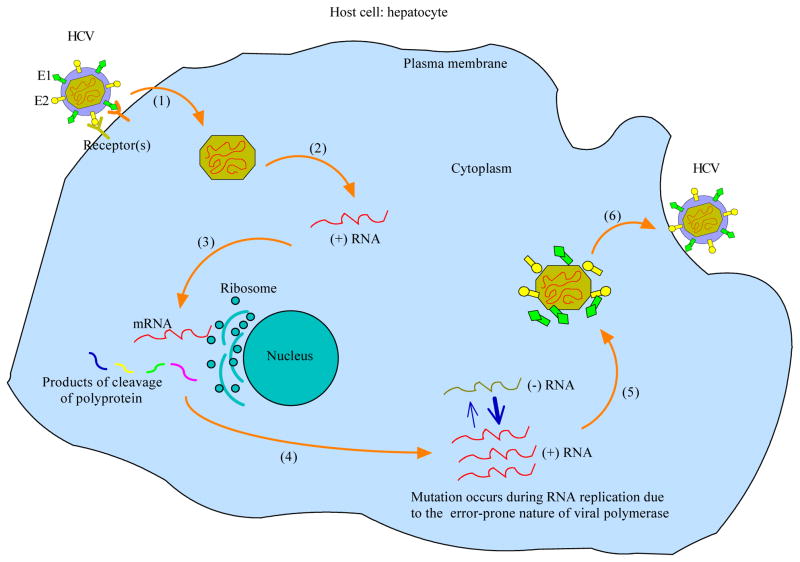

Before describing the model, we use a diagram of the HCV life cycle (Figure 1) as a framework for discussing our current knowledge of virus replication. The exact mechanism by which HCV enters hepatocytes, the primary targets of infection, is still largely unknown. It is presumably receptor-mediated and involves CD81 [27], the human scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1) [28], and other molecules such as claudin-1 [29] and occludin [30]. Following fusion of the viral and cellular membranes, nucleocapsid enters the cytoplasm of the host cell and releases a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome (uncoating). This genome serves, together with newly synthesized RNAs, multiple roles within the HCV life cycle: as a messenger RNA (mRNA) for translation to produce a large polyprotein, as a template for HCV RNA replication, and as a nascent genome that is packaged in progeny virus particles. The generated polyprotein is then cleaved by several enzymes including the NS3-4A serine protease to produce 10 viral proteins: the structural proteins (the core protein C, glycoproteins E1 and E2), a small integral membrane protein p7, and the nonstructural (NS) proteins NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B. This is followed by RNA replication that occurs in a specific cytoplasmic membrane alteration, termed the “membranous web”, whose formation is induced by the integral membrane protein NS4B [31]. The process of RNA synthesis is not fully characterized, but is likely to be semi-conservative and asymmetric [32]: the positive-strand genome RNA serves as a template for the synthesis of a negative-strand intermediate; the negative-strand RNA then serves as a template to produce multiple nascent genomes. Both of these steps are catalyzed by the NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). In the meantime, structural proteins E1, E2 and C have matured. Together with progeny positive-strand genomes, they assemble and are ready for vesicle fusion at the host cell plasma membrane, after which new virions are released into the extracellular milieu by exocytosis.

Figure 1. HCV life cycle.

(1) Following viral binding, receptor-mediated endocytosis and membrane fusion, nucleocapsid enters into the cytoplasm of the host cell; (2) Uncoating of nucleocapsid exposes a positive-strand RNA genome; (3) Internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-mediated translation of the viral genome generates a large polyprotein, which is then proteolytically cleaved by enzymes such as the NS3-4A serine protease to produce 10 viral proteins; (4) Viral polymerase, a product of cleavage, participates in the synthesis of both positive- and negative-strand RNA genomes; (5) Packaging and assembly of progeny virions; (6) Vesicle fusion at the plasma membrane and viral release.

The viral RdRp is an important enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of both positive- and negative-strand RNAs. However, the HCV RdRp has a high error rate, with a misincorporation rate of 10−4–10−5 per copied nucleotide [33]. Furthermore, since the RdRp is devoid of proofreading capacity and other postreplicative repair mechanisms, it cannot correct misincorporations that occur randomly during replication [19]. The high mutation rate, together with rapid HCV replication [34] and the large viral population size, results in progressive diversification of viral genotypes and subtypes in geographically or epidemiologically-linked populations, and in the quasispecies nature of the virus population in a given infected individual [19].

We adapt a mathematical model, which was used to study HIV-1 infection and drug resistance [35], to examine the quasispecies dynamics of HCV before and during treatment. Based on the error-prone nature of the HCV polymerase, hepatocytes infected with wild-type virus are expected to produce both wild-type virus and mutant variants. A simple model including two strains, wild-type and drug-resistant (assuming a single mutation confers a certain level of drug resistance), is described by the following equations:

| (1) |

where T is the number of target cells; Is and Ir are the numbers of cells infected with wild-type and drug-resistant virus, respectively; Vs and Vr represent the numbers of wild-type and drug-resistant virus, respectively. Target cells are produced at rate s and die at rate d. Cells become infected with wild-type virus at rate βs, and infected with drug-resistant virus at rate βr. Once infected, cells die with death rate δ. HCV virions are produced at different rates, ps and pr, by infected cells, Is and Ir, respectively, while the two strains have the same virion clearance rate c. Taking a single mutation into account, we assume that Is with a probability μ produces drug-resistant virus. μ is about 10−4–10−5 per copied nucleotide. We note that model (1) is different from the two-strain model developed during HIV treatment [35] because mutation in HCV occurs during the production of virus rather than at infection like HIV-1. Thus, an infected cell can produce a spectrum of viral variants (a model with multiple viral strains is discussed later). Backward mutation from mutant to wild-type is neglected here, but will be incorporated into the model for comparison later.

2.2 The frequency of the mutant virus before treatment

There are 3 possible steady states (T̄, Īs, V̄s, Īr, V̄r) of model (1): the infection-free steady state E0 = (s/d, 0, 0, 0, 0), the boundary steady state

, and the coexistence steady state

, where

, r =

/

/

,

,

= sβsps/(dcδ) and

= sβsps/(dcδ) and

= sβrpr/(dcδ) are the basic reproductive ratios of the wild-type strain and the drug-resistant strain, respectively. The ratio r represents the relative fitness of drug-resistant to wild-type virus. The steady state Er exists if and only if

= sβrpr/(dcδ) are the basic reproductive ratios of the wild-type strain and the drug-resistant strain, respectively. The ratio r represents the relative fitness of drug-resistant to wild-type virus. The steady state Er exists if and only if

> 1 and Ec exists if and only if

> 1 and Ec exists if and only if

> max(1/(1 − μ),

> max(1/(1 − μ),

/(1 − μ)).

/(1 − μ)).

The above existence conditions also provide threshold conditions for the stability of the steady states. Indeed, we can show that (i) when

< 1/(1 − μ) and

< 1/(1 − μ) and

< 1, E0 is locally asymptotically stable; (ii) when

< 1, E0 is locally asymptotically stable; (ii) when

> 1 and r > 1 − μ, Er is locally stable; and (iii) when

> 1 and r > 1 − μ, Er is locally stable; and (iii) when

> 1/(1 − μ) and r < 1 − μ, Ec is locally stable. The predominance of wild-type virus before treatment suggests

> 1/(1 − μ) and r < 1 − μ, Ec is locally stable. The predominance of wild-type virus before treatment suggests

> 1 and resistance-associated loss of fitness implies

> 1 and resistance-associated loss of fitness implies

<

<

, i.e., r < 1 [23]. These observations suggest that the conditions in (iii) are satisfied because μ is very small. As a consequence, the solutions of model (1) typically converge to the steady state Ec, i.e., both wild-type and drug-resistant viral strains coexist in infected individuals before therapy, as has been shown experimentally [36].

, i.e., r < 1 [23]. These observations suggest that the conditions in (iii) are satisfied because μ is very small. As a consequence, the solutions of model (1) typically converge to the steady state Ec, i.e., both wild-type and drug-resistant viral strains coexist in infected individuals before therapy, as has been shown experimentally [36].

We calculate the frequency of the pre-existing drug-resistant variants in the total virus population from the coexistence steady state Ec. The mutant frequency is given by Φ = Ṽr/(Ṽs + Ṽr), where Ṽs and Ṽr are the steady states of wild-type and drug-resistant virus, respectively. Φ can be simplified to Φ = μ/(1 − r), where r =

/

/

. Therefore, the mutant frequency before therapy depends only on the mutation rate and the relative fitness between mutant and wild-type virus. Since μ is small, the mutant variant remains at a very low level, although it coexists with wild-type in patients before treatment. We also note that the mutant frequency obtained above is equivalent to the result in population genetics where the mutant frequency is derived by mutation-selection balance [37], i.e., the frequency of a deleterious allele is approximately equal to the mutation rate (μ) divided by the selection coefficient (equivalent to 1 − r in the expression of Φ). If the mutant frequency is very low then stochastic models rather than this deterministic model would be needed. Here we only deal with mutants at frequencies that are high enough that deterministic models should be applicable.

. Therefore, the mutant frequency before therapy depends only on the mutation rate and the relative fitness between mutant and wild-type virus. Since μ is small, the mutant variant remains at a very low level, although it coexists with wild-type in patients before treatment. We also note that the mutant frequency obtained above is equivalent to the result in population genetics where the mutant frequency is derived by mutation-selection balance [37], i.e., the frequency of a deleterious allele is approximately equal to the mutation rate (μ) divided by the selection coefficient (equivalent to 1 − r in the expression of Φ). If the mutant frequency is very low then stochastic models rather than this deterministic model would be needed. Here we only deal with mutants at frequencies that are high enough that deterministic models should be applicable.

2.3 Increase of the mutant frequency following treatment

The HCV NS3-4A serine protease plays an important role in viral polyprotein processing, cleaving at the NS3-4A junction and all downstream sites. Telaprevir, a new protease inhibitor, has been developed to block this step in the viral life cycle [12] and has been shown to profoundly reduce the plasma viral load in infected individuals [13, 23]. This is not surprising since the products of polyprotein cleavage are needed to mediate viral RNA replication and virion assembly (Figure 1). Assuming εs and εr are the drug efficacies of telaprevir in blocking viral production for wild-type and drug resistant virus, respectively, where 0 ≤ εs, εr ≤ 1, the model under treatment with the protease inhibitor becomes

| (2) |

Assuming T remains at the pretreatment steady state level, T0 = cδ/[(1−μ)psβs], over a short period of time after drug administration, and ignoring the term μ(1 − εs)psIs in the Vr equation (because μ is ~ 10−4–10−5 [33] and εs is close to 1 [38]), we can reduce Eq. (2) to a simpler system. The solution of the simplified system is Vs(t) = C1eλ1t + C2eλ2t, Vr(t) = C3eλ3t + C4eλ4t, where λi, i = 1, 2, 3, 4, are the eigenvalues of the system, given by and , with Δ1 = (c + δ)2 − 4[cδ − (1 − εs)(1 − μ)psβsT0] and Δ2 = (c + δ)2 − 4[cδ − (1 − εr)prβrT0], which using the expression of T0 can be simplified to Δ1 = (c + δ)2 − 4εscδ and . In Appendix A, we show that λi < 0 and Ci > 0 for i = 1, 2, 3, 4.

The mutant frequency following treatment is then given by the following function of t,

| (3) |

which depends on c, δ, μ, εs, εr, r, and the time t since therapy began.

To study the change of the mutant frequency Φ(t) after drug administration, we have to determine the drug efficacy of telaprevir for each strain. The effectiveness of a drug against wild-type virus can be approximated by a simple function [39] , where C(t) is the drug concentration, IC50 is the concentration of drug needed to inhibit viral production by 50%, and h is the Hill coefficient. Based on the pharmacodynamics of telaprevir, the drug efficacy for the wild-type strain was calculated to be 0.9997 (median) [40], which is consistent with the 3–4 log first-phase drop of plasma HCV RNA levels when telaprevir was administered in monotherapy [13]. Similarly, for the mutant virus with n-fold resistance, i.e., an n-fold increase in IC50, we have . From the equations of εs(t) and εr(t), we obtain . Because the protease inhibitor is given frequently, we assume both εs and εr are constants, which are used in the following simulations.

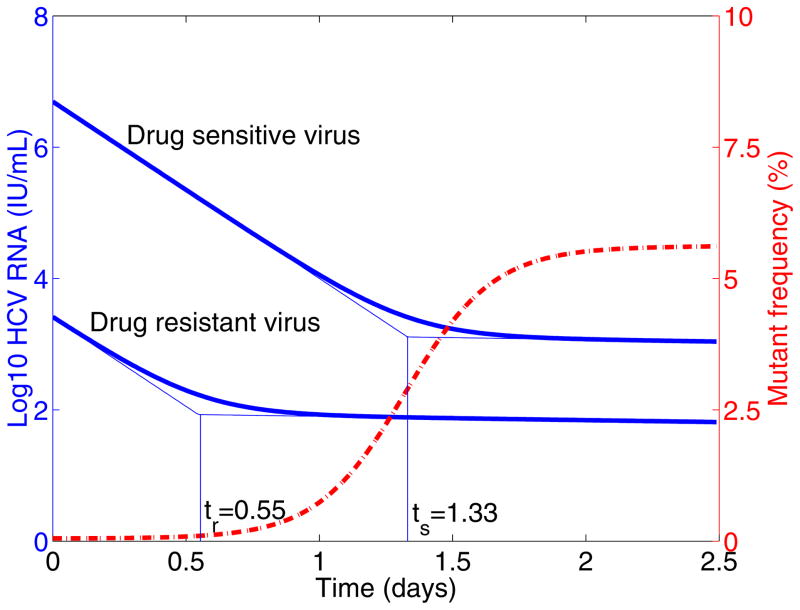

Plotting Φ(t) with typical parameter values and constant drug efficacy shows that the mutant frequency increases substantially from the pre-existing low level (< 1%) to > 5% within ~ 2 days following treatment (Figure 2). This is in agreement with the results in [25]. The rapid increase in mutant frequency does not necessarily mean that the drug-resistant viral variant grows this rapidly following the telaprevir treatment. In fact, taking a close look at the eigenvalues of the system, we find λ3 < λ1 < λ2 < λ4 < 0 (Appendix A). This implies that both wild-type and drug resistant viruses experience a two-phase decline when we assume T = T0 over a short time interval following treatment (see below for a time-varying population of target cells). Furthermore, the drug-resistant strain decreases slightly more rapidly than the wild-type strain during the first phase because λ3 < λ1 < 0 and the difference between λ1 and λ3 is small (Appendix A) as εs is close to 1, whereas it decreases slightly slower than wild-type strain in the second-phase viral decline (λ2 < λ4 < 0 and λ4 − λ2 is small). An interesting result is that the duration of the first-phase viral decline of drug-resistant virus is shorter than that of wild-type virus (Figure 2). Denoting by ts the time at which the second-phase decline of wild-type virus begins and tr the time at which the second-phase decline of drug-resistant virus begins, we show that tr < ts in Appendix A. Consequently, the increase of the mutant frequency following treatment is not due to the rapid growth of drug-resistant viral variant. Rather, it is due to a longer first-phase decline of wild-type virus, unveiling the pre-existing mutant variant.

Figure 2. Mutant frequency and virus dynamics after treatment.

The target cell level is assumed to be the pre-treatment steady state T0. Thick solid line is the viral load and dashed line is the mutant frequency after therapy. ts is the time at which the second-phase decline of wild-type virus begins, and tr is the time at which the second-phase decline of drug resistant virus begins. Model parameters are: c = 6.2 day−1 [34], δ = 0.14 day−1 [34], μ = 10−4 per copied nucleotide [33], εs = 0.9997 [38], the Hill coefficient is h = 2 [69]. We assumed the mutant, for example T54A, confers 12-fold resistance and

/

/

=0.81 [23]. We obtained the eigenvalues λ1 = −6.2, λ2 = −0.14, λ3 = −6.2048, λ4 = −0.1352, and ts = 1.33 day, tr = 0.55 day.

=0.81 [23]. We obtained the eigenvalues λ1 = −6.2, λ2 = −0.14, λ3 = −6.2048, λ4 = −0.1352, and ts = 1.33 day, tr = 0.55 day.

2.4 Competition between the two strains during therapy

In the above, successful suppression of the pre-existing mutant virus regardless of its drug resistance level is due to the assumption that the number of susceptible target cells remains at a constant baseline level, T0 = cδ/[(1 − μ)psβs], following telaprevir treatment. If we describe the dynamics of target cells as in model (2), then drug-resistant virus is able to emerge and dominate the virus population under certain conditions.

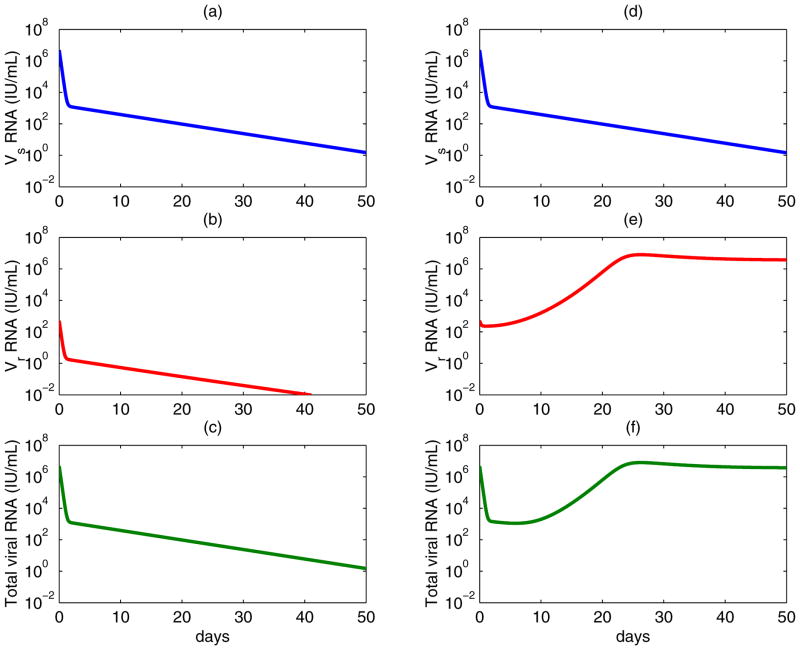

Considering model (2), we define the reproductive ratios under treatment, and . Before treatment, both strains coexist, but resistant virus remains at a very low level (Rs > Rr > 1). During treatment, becomes less than 1 because of the efficiency of the protease inhibitor in blocking production of wild-type virus. Consequently, wild-type virus is usually successfully suppressed. If mutation only confers a low level of drug resistance (εr is large), then drug-resistant virus will also be suppressed (Figure 3, left column). However, if mutation confers high-level drug resistance (εr is small), may be greater than 1. Therefore, the pre-existing drug-resistant virus will outcompete wild-type and dominate the virus population under this condition (Figure 3, right column).

Figure 3. Competition between wild-type (upper panels) and drug-resistant virus (middle panels) during therapy (Eq. (2)).

The total viral levels are plotted in the lower panels. Left column: assuming the mutant, for example V36A/M, confers 3.5-fold resistance and

/

/

=0.98 [23]. Both wild-type and drug-resistant virus are suppressed. Right column: assuming the mutant, for example A156V/T, confers 466-fold resistance and

=0.98 [23]. Both wild-type and drug-resistant virus are suppressed. Right column: assuming the mutant, for example A156V/T, confers 466-fold resistance and

/

/

=0.45 [23]. Wild-type virus is suppressed, whereas drug-resistant virus arises and dominates the virus population, which results in a viral rebound in the total viral level. The values of parameters used are [26, 34]: s = 7.5 × 105 cells mL−1 day−1, d = 0.01 day−1, βs = βr = 10−7 mL day−1 virions−1, μ = 10−4 per copied nucleotide, c = 6.2 day−1, δ = 0.14 day−1, ps = 10 virions cell−1 day−1, εs = 0.9997, and the Hill coefficient is h = 2.

=0.45 [23]. Wild-type virus is suppressed, whereas drug-resistant virus arises and dominates the virus population, which results in a viral rebound in the total viral level. The values of parameters used are [26, 34]: s = 7.5 × 105 cells mL−1 day−1, d = 0.01 day−1, βs = βr = 10−7 mL day−1 virions−1, μ = 10−4 per copied nucleotide, c = 6.2 day−1, δ = 0.14 day−1, ps = 10 virions cell−1 day−1, εs = 0.9997, and the Hill coefficient is h = 2.

2.5 The effect of backward mutation

In addition to forward mutation, a backward mutation may occur that restores the original viral sequence. We compare model (1) (no backward mutation) with the following model (before treatment, i.e., εs = εr = 0) including both forward and backward mutations. Here we are assuming a single nucleotide change confers resistance, such as the G→A change that mediates the V36M mutation (i.e., the codon changes from GTG to ATG [41]), so that back mutation occurs at the same rate as forward mutation.

| (4) |

Before drug therapy (εs = εr = 0), patients have relatively constant levels of viremia which we assume corresponds to being at the infected steady state, in which the two viral strains coexist. In Appendix B, we derive the steady states and calculate the mutant frequency before treatment. The mutant frequency can be approximated by , which is less than the mutant frequency in the absence of backward mutation, Φ = μ/(1 − r). However, the difference between them is minuscule since μ is small. Numerical results also suggest that including backward mutation in model (1) only has minor effects on the steady state viral loads and the pre-treatment mutant frequency (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of backward mutation on the steady states and the mutant frequency before treatment*

| Model | Steady state of the wild-type virus V̄s | Steady state of the resistant virus V̄r | Mutant frequency Φ = V̄r/(V̄s + V̄r) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without backward mutation (Eq. (1)) | 4.9386 × 106 IU/mL | 1.2350 × 103 IU/mL | 2.5000 × 10−4 |

| With backward mutation (Eq. (4)) | 4.9386 × 106 IU/mL | 1.2348 × 103 IU/mL | 2.4996 × 10−4 |

Model parameters used to obtain the steady states of Vs and Vr are [26, 34]: d = 0.01 day−1, ps = 10 virions cell−1 day−1, μ = 10−4, c = 6.2 day−1, δ = 0.24 day−1. Assuming T (0) is about 1.5 × 106 cells/mL and Vs(0) is about 5 × 106 IU/mL at the baseline before treatment, we have βs = 10−7 mL day−1 virions−1 and s = 7.5 × 105 cells mL−1 day−1. For simplicity, we assume that wild-type and resistant viruses differ only in their replication capacities. We choose βr = βs = 10−7 mL day−1 virions−1 and pr = 6 virions cell−1 day−1 (supposing that a single-mutant variant, for example R155K/T, confers ~10-fold resistance and has a relative fitness of ~0.6 compared with wild-type virus [23]).

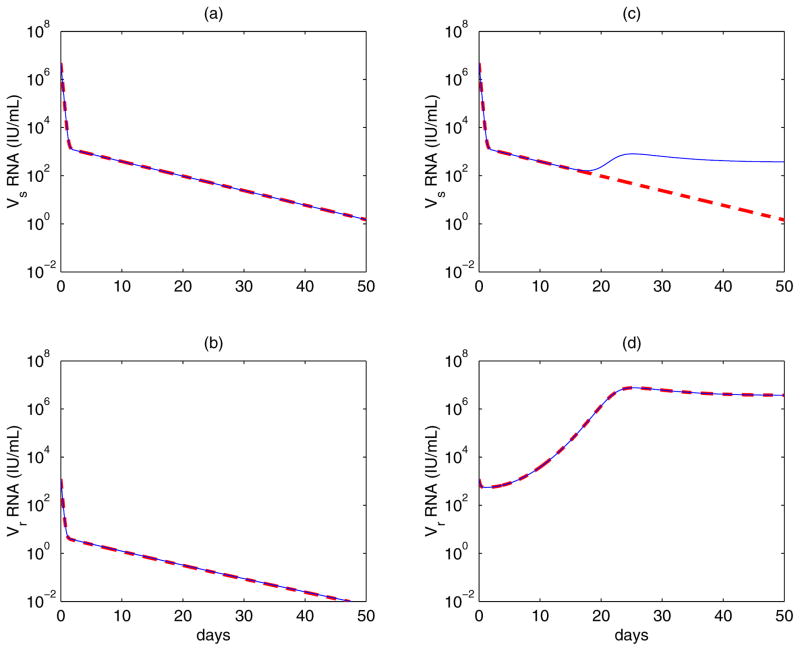

It is interesting to study the contribution of mutation to the dynamics of virus during therapy. Supposing that wild-type and mutant virus are both at their pretreatment baseline levels, we compare virus dynamics of the model given by Eq. (4) with the model in which both forward and backward mutations are ignored (μ = 0 in (4)). Figure 4 shows the dynamics of both wild-type and drug-resistant viruses during therapy. For a mutation that confers a low level of drug resistance (for example, the mutant V36M/A confers 3.5-fold resistance [23]), inclusion of mutation has a negligible effect on the dynamics of both viral strains (Figure 4, left column). Even if mutation confers high-level resistance (for example, the A156V/T mutant confers 466-fold resistance [23]), the contribution of mutation to the level of the drug-resistant viral variant is still minor. However, in this case, wild-type virus can be maintained by backward mutation at a low level rather than being completely suppressed (Figure 4, right column). These observations are not surprising because in the presence of effective therapy targeted against wild-type virus the mutation from wild-type to drug-resistant strain makes a negligible contribution to the mutant viral load since it occurs at rate μ(1 − εs). Therefore, mutations only play a minor role in the dynamics of drug resistant virus during treatment.

Figure 4. Contribution of mutation to the dynamics of wild-type and drug-resistant virus during treatment.

Assuming there is no mutation during treatment (thick dashed line) and there exist both forward and backward mutations during therapy (thin solid line). Left column: assuming the mutant confers 3.5-fold resistance and

/

/

=0.98 [23]. The solid and the dashed lines almost overlap, which suggests that mutation has a negligible effect on the evolution of both strains when the mutation confers a low level of drug resistance. Right column: assuming the mutant confers 466-fold resistance and

=0.98 [23]. The solid and the dashed lines almost overlap, which suggests that mutation has a negligible effect on the evolution of both strains when the mutation confers a low level of drug resistance. Right column: assuming the mutant confers 466-fold resistance and

/

/

=0.45 [23]. Mutation still does not contribute much to the evolution of drug-resistant virus, which emerges and dominates the virus population. However, wild-type virus is maintained at a low level by backward mutation rather than being completely suppressed. The values of parameters used are [26, 34]: s = 7.5× 105 cells mL−1 day−1, d = 0.01 day−1, βs = βr = 10−7 mL day−1 virions−1, μ = 10−4 per copied nucleotide, c = 6.2 day−1, δ = 0.14 day−1, ps = 10 virions cell−1 day−1, εs = 0.9997, and h = 2.

=0.45 [23]. Mutation still does not contribute much to the evolution of drug-resistant virus, which emerges and dominates the virus population. However, wild-type virus is maintained at a low level by backward mutation rather than being completely suppressed. The values of parameters used are [26, 34]: s = 7.5× 105 cells mL−1 day−1, d = 0.01 day−1, βs = βr = 10−7 mL day−1 virions−1, μ = 10−4 per copied nucleotide, c = 6.2 day−1, δ = 0.14 day−1, ps = 10 virions cell−1 day−1, εs = 0.9997, and h = 2.

Without mutation (μ = 0), Eq. (4) represents a standard two-strain model in which the two strains of virus compete for the same resource (susceptible target cells). Thus, the competitive exclusion principle applies—when the drug-resistant strain has a higher fitness under treatment ( ), it outcompetes the wild-type strain.

2.6 The model with hepatocyte proliferation

Hepatocyte proliferation is important in liver regeneration [42] and can compensate for loss of hepatocytes during HCV infection. It can generate new target cells and has been included in mathematical models [43, 44]. Models with proliferation can explain complex HCV RNA profiles, such as the triphasic viral decay observed during treatment of some patients [43]. Here we incorporate proliferation of both uninfected and infected hepatocytes into model (1) and study the effects on the pretreatment mutant frequency and the evolution of drug resistance during therapy. The model with hepatocyte proliferation is

| (5) |

where uninfected hepatocytes (i.e. target cells), hepatocytes infected with wild-type virus, and hepatocytes infected with drug resistant virus can proliferate with maximum proliferation rates ρT, ρs, and ρr, respectively. Tmax is the maximum level of the total hepatocyte population. It should be noted that the value of the target cell recruitment rate, s, is different from that in model (1) because of the inclusion of proliferation in the T equation. Also, s ≤ dTmax so that in the uninfected liver T ≤ Tmax. Another version of this model presented elsewhere [26] includes a constant population of cells in the liver that are not susceptible to infection in the density-dependent terms of Eq. (5). This does not affect the behavior of the model but does affect parameter estimates when the model is compared with data [26].

We are interested in the pretreatment mutant frequency. In Appendix C, we show that the mutant frequency is the same as that of model (1) if ρs = ρr, which we expect to be the case since it is unlikely that a drug resistance mutation would affect the growth rate of an infected cell.

If we ignore mutations during treatment, then the model with hepatocyte proliferation becomes

| (6) |

This is not a standard two-strain competition model because the two strains can coexist under certain conditions. Substituting V̄s = (1− εs)psĪs/c and V̄r = (1− εr)prĪr/c into the Is and Ir equations, respectively, we obtain

| (7) |

and

| (8) |

If ρs = ρr, then it is obvious that the two strains cannot coexist because (1 − εs)βsps < (1 − εr)βrpr. If ρs ≠ r, then it is possible that the two strains coexist. In this scenario, from (7) and (8) we have , which yields . Combining (7) or (8) with the T equation in Eq. (6), we can obtain the steady states Īs and Īr. Since their expressions are complicated, we do not present them here.

Although the two strains can coexist under certain conditions, wild-type virus is in general successfully suppressed because the inhibitor telaprevir is very effective against wild-type virus. Whether drug-resistant virus will also be suppressed depends on its reproduction capacity, proliferation potential of cells infected with resistant virus, and the drug efficacy εr.

3 A multi-strain model and quasispecies dynamics

3.1 Model formulation

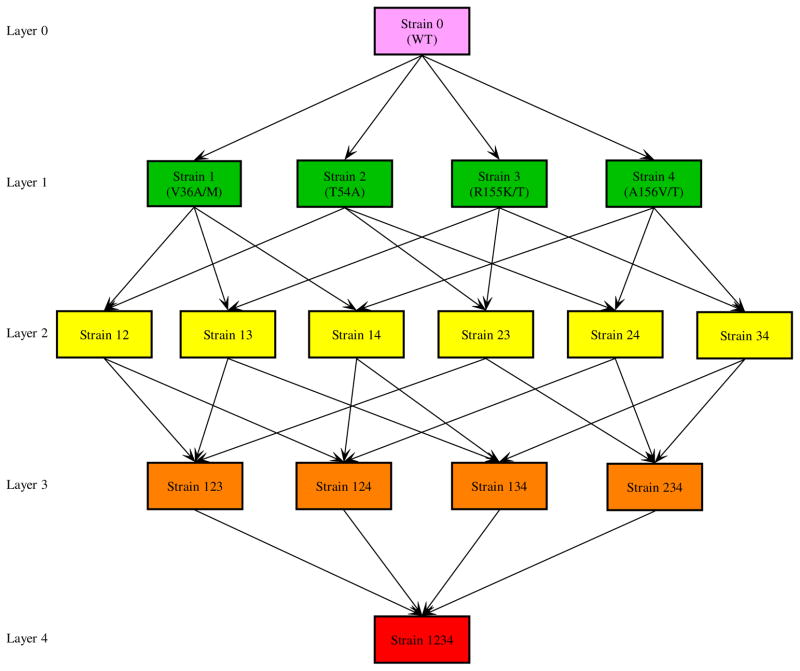

During treatment with telaprevir, mutations mainly occur at 4 positions in the HCV NS3 protease catalytic domain, i.e., at amino acids: 36, 54, 155, and 156 [23, 25]. Here we consider the mutations occurring at these 4 positions and develop a multi-strain viral dynamic model. We assume that there is no backward mutation and that the probability of a forward mutation occurring at each amino acid is identical, denoted by μ. A schematic diagram of the mutations between these viral variants is given in Figure 5. A different multi-variant viral dynamic model was used by Adiwijaya et al. [45] to quantify the antiviral response to telaprevir and the in vivo fitness of different variants in HCV patients.

Figure 5. Mutation diagram.

From the topmost (layer 0) to the bottommost (layer 4) are the wild-type, single-mutant, double-mutant, 3-mutant, and 4-mutant strains. Backward mutation is not considered. Mutations between strains that lead to transitions beyond one layer are not shown but are considered in the multi-strain model. For example, the mutation from the wild-type (layer 0) to strain 12 (layer 2) or strain 123 (layer 3) is not plotted in the diagram.

The full model with 4 positions where mutation is possible, without considering backward mutations (i.e., once a position mutates it can not mutate again), is given by

| (9) |

In the first two equations, the strain index j is in the set Ω (j ∈ Ω), where Ω={0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 12, 13, 14, 23, 24, 34, 123, 124, 134, 234, 1234}. Strain 0 represents wild-type virus; strains 1, 2, 3, 4 represent the viral strains with mutations occurring at positions 36, 54, 155, and 156, respectively. Strains ij, i, j = 1, 2, 3, 4 and i < j, are the strains with double mutations occurring at positions i and j. Strains ijk, i, j, k = 1, 2, 3, 4 and i < j < k, and strain 1234 can be defined similarly (Figure 5). In this model, there is conservation of viruses as they mutate within the self-contained system of 16 strains.

The basic reproductive ratio for each strain is

= βipis/(dcδ), i ∈ Ω, and we define the ratio ri =

= βipis/(dcδ), i ∈ Ω, and we define the ratio ri =

/

/

, i ∈ Ω\{0}. ri represents the relative fitness between mutant and wild-type virus. In the absence of selective drug pressure, ri falls within the interval [0, 1].

, i ∈ Ω\{0}. ri represents the relative fitness between mutant and wild-type virus. In the absence of selective drug pressure, ri falls within the interval [0, 1].

3.2 The frequency of the pre-existing viral variants before therapy

A tedious but straightforward calculation yields the mutant frequency of the pre-existing viral variants before treatment. The viral load of each strain is

| (10) |

where V0 is the steady state of wild-type virus before treatment.

The above defines a recursive scheme, which allows us to orderly calculate the pretreatment steady states of the double-mutant variants (Vij), 3-mutant variants (Vijk), and 4-mutant variant (V1234):

| (11) |

It follows that the pretreatment steady state level of an m-mutant viral variant is of the order of μmV0. The ratio of the m-mutant variant to wild-type virus, Vm-mutant/V0, depends on the mutation rate μ, the relative fitness of the m-mutant strain and all the strains with fewer mutations. The ratio does not depends on the relative fitness of the strains with more mutations because we did not consider backward mutation in the model.

The frequency of the pre-existing viral strain i (i ∈ Ω) before treatment is then Φi = Vi/Vtotal, where . The frequency Φi depends on the mutation rate μ and the relative fitness of all mutant strains, ri, i ∈ Ω\{0}.

The above formulation of the multi-strain model and the calculation of the pre-existing mutant frequency can be extended to include n possible mutations without difficulty. For example, suppose that mutations occur mainly at n positions and an m-mutant variant, Vm–mutant, has mutations occurring at the first m positions. Then the pre-existing steady state of this strain is

In the above expression, the steady states of the other viral variants with fewer mutations can be obtained recursively as in the scheme of equation (10). In this way, we can calculate the frequency of all pre-existing variants in a general model with n possible mutations.

The multi-strain model (Eq. 9) includes all possible viral strains that bear mutations at the four positions. However, only a few mutant strains were detected during treatment with telaprevir [23–25]. Specifically, of all the strains with two or more mutations, only strain 13 (36/155) and strain 14 (36/156) were frequently observed. Considering only these observed strains, the strain index set Ω becomes Θ = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 13, 14}. Setting the appropriate ri to 0 in Eqs. (10) and (11), the pretreatment steady states of the mutant strains are

| (12) |

where V0 is the pretreatment steady state of the wild-type virus and ri =

/

/

, i ∈ Θ\{0}, represents the relative fitness of strain i.

, i ∈ Θ\{0}, represents the relative fitness of strain i.

Using the in vitro estimates of the relative fitness (assuming the fitness of wild-type virus is 1) of each mutant strain in [23], we obtain the mutant frequency of the pre-existing viral variants before therapy (Table 2). For the single-mutant variant, the frequency is determined by its relative fitness —the larger the relative fitness, the higher the frequency. For the strain with two mutations, the frequency also relies on the relative fitness of those single-mutant strains that can mutate to the double-mutant strain. Although various mutant variants may exist before drug treatment [36], they only account for a very small fraction of the entire virus population. New technologies such as pyrosequencing [46] may allow one to determine the frequency of rare mutants, but to our knowledge this has not been done for the patients in the study we have analyzed [25].

Table 2.

Estimated mutant frequency of the pre-existing viral variants before therapy*

| Mutant viral variants | Relative fitness** | Pretreatment frequency |

|---|---|---|

| V36A/M | 0.98 | 5.00 × 10−3 |

| T54A | 0.81 | 5.23 × 10−4 |

| R155K/T | 0.62 | 2.62 × 10−4 |

| A156V/T | 0.45 | 1.81 × 10−4 |

| 36/155 | 0.82 | 2.87 × 10−6 |

| 36/156 | 0.67 | 1.54 × 10−6 |

A typical HCV infected patient has a viral load > 106 per ml or > 1010 virions in the total extracellular body water. Thus, the total number of each pre-existing viral variant is sufficiently large (> 104 virions) that prediction via a deterministic model is justified.

Relative fitness is from the in vitro estimates in [23].

3.3 Quasispecies dynamics during therapy

As shown in previous sections, mutation during treatment has a minor effect on the dynamics of viral variants. Mutation is capable of generating low levels of viral variants that would otherwise be completely suppressed due to their fitness disadvantage, but mutation itself cannot determine which strain(s) will dominate the virus population during therapy. Here we neglect all the mutations generated during therapy. Then the multi-strain model under treatment becomes

| (13) |

where i ∈ Θ = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 13, 14}.

The reproductive ratio for each strain under therapy is: , i ∈ Θ. The above model represents a multi-strain competition system. The competitive exclusion principle also applies here. Any two viral strains cannot coexist ultimately unless they have the same reproductive ratio. Furthermore, only the viral strain with the largest reproductive ratio will persist during therapy. All the other strains with lower reproductive ratios will die out. Mathematically, if , for any j ∈ Θ and j ≠ i, then the solution of the system will converge to the steady state Ei, in which only strain i is present. If two or more strains have the same reproductive ratio, then they can coexist ultimately during therapy if their reproductive ratios are greater than 1 and also greater than the reproductive ratios of other strains.

4 Conclusions and discussions

Much of the recent HCV drug discovery effort has been focused on generating new therapies for HCV genotype 1 infection because of its prevalence and relatively poor response to therapy with PEG-IFN and RBV. Direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV have been suggested to be an attractive strategy whose objective is to achieve a greater response rate, with shorter treatment duration and better tolerability. However, the development of drug resistance has been a major limitation for such treatment options. The high HCV replication rate and the error-prone nature of viral RNA polymerases generate a large number of mutant viral variants, termed a quasispecies, from which variants resistant to specific drugs can be selected during treatment. Since these drug-resistant viral variants have a fitness advantage against wild-type virus in the presence of drug pressure, they are able to evolve quickly and dominate the virus population.

The HCV NS3-4A serine protease is not only involved in viral polyprotein processing but also contributes to HCV persistence by helping HCV escape the IFN antiviral response through its ability to block retinoic acid-inducible gene I and toll-like receptor-3 signaling [47, 48]. Therefore, the NS3-4A protease has become an ideal target for the development of new anti-HCV agents. Telaprevir, a new protease inhibitor, has demonstrated substantial antiviral activity in clinical studies [13, 23–25]. Administration of telaprevir even in monotherapy resulted in ~ 4-log reduction of the plasma viral load in HCV genotype 1 infected patients after 14 days [13]. However, drug-resistant viral variants were detected at high frequencies within a few days during the dosing period. The exact mechanisms underlying emergence of viral variants such a short time after initiation of therapy is not fully characterized.

This paper studies the prevalence of the pre-existing HCV variants and the evolution of drug resistance in patients treated with a direct-acting antiviral agent such as telaprevir. We began with a simple model including two viral strains: wild-type and drug-resistant. The host cell infected with wild-type virus can produce both wild-type virus and a small fraction of drug-resistant virus due to mutations. The two strains coexist before treatment, although drug-resistant virus only accounts for a very small proportion of the virus population. The pre-existing mutant frequency, defined as the ratio of the number of the mutant virus to the total virus before treatment, is Φ = μ/(1 − r), which is dependent only on r, the relative fitness between drug-resistant and wild-type virus, and μ, the mutation rate. Using a simplified two-strain model, we obtained an analytical solution of the mutant frequency following treatment with telaprevir. We showed that the rapid increase in the mutant frequency during therapy may not reflect the rapid replication of the pre-existing viral variants, but rather could be a consequence of the rapid and profound decline of wild-type virus, which uncovers the pre-existing mutant virus.

We studied the effects of mutation and hepatocyte proliferation on the pre-treatment mutant frequency and the evolution of drug resistance during therapy. Using the two-strain model, we showed that backward mutation has a negligible effect on the pretreatment mutant frequency. Because the protease inhibitor is highly effective against wild-type virus, both forward and backward mutations do not have a noticeable impact on the dynamics of drug-resistant virus. However, when drug-resistant virus dominates the virus population, backward mutation is able to maintain the wild-type virus at a very low level. Therefore, mutations during therapy do not contribute much to the dynamics of HCV variants. They cannot determine which strain will dominate the virus population. The dynamics of each viral strain are primarily determined by its relative fitness. Specifically, they are determined by the tradeoff between the reduced susceptibility to the protease inhibitor and resistance-associated fitness loss of the mutant virus. When hepatocyte proliferation is included in the models, the analysis becomes more complicated. In a specific case, we showed that the mutant frequency before treatment was not altered. During treatment, wild-type virus is usually suppressed by the effective agent. Whether drug-resistant virus will also be suppressed depends on the proliferation potential of cells infected with resistant virus, relative fitness of the mutant, as well as the drug efficacy. Even if the infection persists, the infected steady state can be unstable and periodic solutions may exist for an open set of parameter values [49].

We also developed a general multi-strain viral dynamic model that considers mutations among various viral strains. We derived the frequency of the pre-existing mutant variants before therapy. Without backward mutation, the frequency depends on the relative fitness of all strains that have fewer mutations. Even though including all the mutations can generate low levels of viral variants that would otherwise be significantly suppressed because of fitness disadvantage in the presence of drug pressure, the quasispecies dynamics are principally determined by the relative fitness of each strain. Mathematically, as De Leenheer and Pilyugin showed in [50], the steady state corresponding to the fittest strain in the model without mutations is globally asymptotically stable. With small perturbations due to mutations, global stability of this steady state is still preserved [50]. A few issues need also to be kept in mind when one discusses the dynamics of various viral variants during therapy. First, although only a few of all possible variants are frequently detected in clinical studies, failure to observe the other viral strains during treatment does not imply that they are not present. Indeed, even if certain viral strains are predicted to die out from the above analysis, in reality they may be present because they can be generated by mutation. However, such strains should remain at very low levels and may exist below the detection limit of assays. Second, when we say a viral strain will die out or survive, we are referring to its steady state level (a long-term behavior). During the short dosing period of telaprevir in clinical trials, even the viral variant with the lowest fitness might be observed.

The emergence of HCV variants at high frequencies is faster than that seen in HIV. This difference can be explained by several factors related to our calculations. (1) Preexistence of drug-resistant variants. The fidelity of reverse transcriptase for HIV may be higher than that of RdRp for HCV [51, 52]. Thus, the intrinsic HCV mutation rate may be higher than that of HIV [53]. The frequency of pre-existing HCV mutants (which is proportional to μm for m-mutants, see calculations in Section 3.2) in the total virus population is higher than that of HIV. (2) Effectiveness of therapy. HCV protease inhibitors such as telaprevir are very effective in inhibiting the replication of wild-type virus. As we showed in Section 2.3 and Figure 2, a long and profound first-phase decline of wild-type virus uncovers the pre-existing mutant variants very fast. (3) Room for drug-resistant virus growth. Homeostatic hepatocyte proliferation can compensate for loss of liver cells during HCV infection. This generates new target cells and provides room for growth of pre-existing resistant HCV variants after therapy initiation. Some other factors such as the viral reading frames and the different turnover of the viral nucleic acid acting as a source of new viral genomes may also contribute to the rapid emergence of HCV drug resistance [54].

The prevalence of the pre-existing HCV variants has been observed in experiments. McPhee et al. [55] examined the baseline prevalence of HCV variants resistant to protease inhibitors using a highly sensitive assay (limit of detection < 0.1% of the total population). In three of eight patients, they detected the A156T variant at a frequency of 0.36%-0.75%. Cubero et al. [56] reported a similar mutant frequency (0.78%) of the A156T mutant in a chronic hepatitis C patient never treated with NS3-protease inhibitors. This frequency is higher than what we obtained in Table 2. The discrepancy can be explained either by a larger in vivo fitness than that in Table 2 estimated from in vitro experiments or by compensatory mutations (not considered in our models, see [57] that studies how compensatory mutations affect the emergence of drug resistance), which allow partial fitness recovery of the mutant variants. It has been reported that three second-site mutations, P89L, Q86R, and G162R, were able to partially reverse A156T-associated defects in polyprotein processing and/or replicon fitness without significantly reducing resistance to the protease inhibitor SCH6 [58]. In the study of Cubero et al. [56], they also detected changes at positions 89 and 86 (P89Q and Q86P) along with the A156T mutant. The presence of these mutations might compensate for the A156T-associated fitness loss and result in a higher frequency in untreated patients. The contribution of compensatory mutations to the preexistence of HCV variants and the evolution of drug resistance during treatment requires more in vitro and in vivo studies.

Our calculations may have implications for developing treatment strategies for HCV infection. From expression (11), the steady state viral level of an m-mutant strain is of the order of μm, which implies that a mutant variant will have a very low frequency if it carries more mutations conferring resistance to multiple drugs. In fact, in clinical trials, HCV viral variants with three or more drug-resistant mutations have seldom been identified so far. This raises the chance of success of a strategy that combines several specific HCV inhibitors targeting different steps of the HCV life cycle. The combination treatment strategy is, in theory, the same as for hepatitis B virus (HBV) [59] and HIV treatment [60]. This idea has been recently confirmed in in vitro studies [61–63]. When replicon cells were treated with a nucleoside HCV polymerase inhibitor in combination with either HCV-796, a non-nucleoside polymerase inhibitor, or telaprevir, the number of drug-resistant viruses was largely reduced [61], suggestive of a lack of cross resistance among the evaluated inhibitors. The data from a chimpanzee model of chronic HCV infection in which one chimp treated with HCV protease and polymerase inhibitors was cured also support further investigation of combination therapy using only direct-acting antiviral agents [64]. Recent clinical trial results have shown that in principle patients can be cured using combinations of direct-acting antiviral agents [65, 66]. Therefore, combination of direct-acting antiviral drugs might one day be the standard therapy for HCV patients.

By calculating the fraction of all possible mutants produced per day, we estimated the number of mutations a combination of direct antivirals would need to overcome to be successful [26]. More clinical data on toxicity and drug-drug-interactions are needed in order to design combination therapies. In addition, in vitro data indicate that telaprevir and IFN act synergistically to inhibit HCV RNA replication and facilitate viral RNA clearance in replicon cells [67]. In clinical studies [25, 68], telaprevir was combined with PEG-IFN-alpha-2a and caused a continued antiviral response during the dosing period. More recent clinical trials [14, 15] showed that treatment with a telaprevir-based regimen significantly improved the SVR rate in patients with genotype 1 HCV. Even in patients with viral breakthrough following telaprevir alone, follow-up treatment with PEG-IFN-alpha-2a and RBV could inhibit growth of both wild-type and resistant variants [25]. These results suggest that HCV variants with reduced sensitivity to telaprevir may remain sensitive to IFN plus RBV. Based on this, both telaprevir and boceprevir were only approved by the FDA for use in combination with PEG-IFN and RBV. If we assume that IFN lowers the viral production rate by a factor (1 − εIF N), then the model including combination therapy of IFN and a protease inhibitor is the same as the model with the protease inhibitor monotherapy except that εr and εr are replaced with and , respectively, where and represent the total drug effectiveness against drug-sensitive and drug-resistant virus, respectively. Thus, the theory presented in this study can be used to also analyze combination therapy data.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were done under the auspices of the US Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-06NA25396, and supported by NIH grants P30-EB011339, P20-RR018754, AI028433, OD011095, and NSF grant DMS-1122290. We also thank the reviewers for their comments that improved the manuscript.

Appendix A: Several inequalities used in the analysis of the two-strain model

1. λ3 < λ1 < λ2 < λ4 < 0

From Δ1 = (c + δ)2 − 4εscδ, it is clear that (c + δ)2 > Δ1 > (c − Δ)2. Thus, we have

and

. Next we show that Δ2 > Δ1. Calculating the difference, we obtain

, where

and

are the reproductive ratios of the resistant and wild-type strains during therapy, respectively. Since we assume that drug-resistant virus is more fit than wild-type virus during therapy, we have that

. Thus, Δ2 > Δ1. Lastly, we show that (c + δ)2 > Δ2. It suffices to show that

, i.e.,

, which holds because wild-type virus is more fit than drug-resistant virus before treatment (

<

<

) and μ is very small (typically μ ≪ εr). Therefore, (c + δ)2 > Δ2 > Δ1 > (c − δ)2. It follows that

and

. Furthermore, from

, we have that λ3 < λ1 < λ2 < λ4 < 0.

) and μ is very small (typically μ ≪ εr). Therefore, (c + δ)2 > Δ2 > Δ1 > (c − δ)2. It follows that

and

. Furthermore, from

, we have that λ3 < λ1 < λ2 < λ4 < 0.

2. Ci > 0, i = 1, 2, 3, 4

-

Notice that and

Δ1 = (c + δ)2 − 4εscδ. C1 > 0 is equivalent to . Thus, for C1 > 0 it suffices to prove that . If the right hand side is less than 0, then the inequality automatically holds. If the right hand side is greater than 0, then we only need to show that Δ1 > (c + δ −2cεs)2, which is equivalent to εs < 1. Hence, Δ1 > (c + δ − 2cεs)2 and C1 > 0.

Because , we have . Thus, .

For simplicity, we introduce a new parameter θ, defined as . Thus, θ < 1. Then C3, C4, and Δ2 can be simplified to , and Δ2 = (c + δ)2 − 4θcδ, which have similar forms to C1, C2, and Δ1, respectively. Following the same arguments as in (i) and (ii), we can prove that C3 > 0 and C4 > 0.

3. tr < ts and tr is an increasing function of εr

Since ts is the time at which two curves C1eλ1t and C2eλ2t intersect, we obtain that . Similarly, we have . Calculating the difference between and , we obtain

| (14) |

where .

Using the common denominator to combine the two fractions in (14), we obtain the numerator

which can be simplified to

| (15) |

Because drug-resistant virus is more fit than wild-type virus during treatment, we have (1 − εs)

< (1 − εr)

< (1 − εr)

. Thus,

since μ is very small. It follows from (15) that

. Thus,

since μ is very small. It follows from (15) that

The last inequality holds because telaprevir is very effective in blocking production of wild-type virus (εs is close to 1) and virus has much faster dynamics than infected hepatocytes (c ≫ δ). Therefore, . Also considering that , we have ts > tr.

Furthermore, we can prove that tr is an increasing function with respect to εr, the efficacy of the protease inhibitor against the drug-resistant strain. As εr decreases (corresponding to a more resistant viral strain), decreases and Δ2 = (c + δ)2 −4θcδ increases. Rearranging , we have , where . Taking derivative of f(θ) with respect to θ, we obtain

The numerator of the above fraction can be simplified to 2c2(2θδ − c − δ), which is less than 0 because θδ < c and θδ< δ. Thus, as θ decreases, f(θ) increases. Consequently, C3/C4 decreases and decreases. This shows that tr is an increasing function of εr. Thus, for a mutant strain with high-level drug resistance (a small εr), tr is small.

Appendix B: The mutant frequency in the model with backward mutation

There are two possible steady states of Eq. (4) before treatment: the infection-free and infected (coexistence) steady states. We are interested in the latter one. From the Is and Vs equations, we obtain μprβrT̄V̄r = [cδ − (1 − μ)psβs T̄]V̄s, where T̄, V̄s and V̄r represent the steady states of uninfected target cells, wild-type and drug-resistant virus, respectively. Similarly, from the Ir and Vr equations, we obtain μpsβsT̄V̄s = [cδ − (1 − μ)prβrT̄]V̄r. Thus, the two strains coexist only when (1 − μ)psβsT < cδ and (1 − μ)prβrT̄ < cδ. From the above two equations, we obtain an equation that the steady state of uninfected hepatocytes, T̄, must satisfy (1 − 2μ)psβsprβrT̄2 − (1 − μ)cδ(psβs + prβr)T̄ + (cδ)2 = 0, which has two solutions:

| (16) |

Ignoring μ, we have two approximate solutions: (choosing “+” in (16)) and (choosing “−” in (16)). Because of the conditions for the existence of the coexistence steady state and the assumption that βr < βs and pr < ps, only T̄2 is feasible. Thus, the mutant frequency before treatment is , where

Using T̄2, Φ can be further simplified to

| (17) |

where r =

/

/

. It is clear that Φ depends only on μ and r.

. It is clear that Φ depends only on μ and r.

It follows from (17) that F can be approximated by

| (18) |

which is less than

, the mutant frequency in the model without considering backward mutation. In fact, it can be proved rigorously that Φw < Φwo, where Φw represents the mutant frequency with backward mutation (defined in (17)) and

is the mutant frequency without backward mutation. For the proof, it suffices to show that

. This inequality is equivalent to r < 1, which holds because resistant virus is less fit than wild-type virus in the absence of treatment (

<

<

). Therefore, Φw < Φwo. However, from the approximation of Φw (Eq. (18)), we observe that the difference between Φw and Φwo is miniscule. This shows that backward mutation only plays a minor role in the pre-treatment mutant frequency.

). Therefore, Φw < Φwo. However, from the approximation of Φw (Eq. (18)), we observe that the difference between Φw and Φwo is miniscule. This shows that backward mutation only plays a minor role in the pre-treatment mutant frequency.

Appendix C: The pretreatment mutant frequency in the model with hepatocyte proliferation

From the Vs and Vr equations of model (5), we have

and

. Substituting into the Is and Ir equations, we obtain

and

. If ρs = ρr, from the above two equations we have

, which yields

. Substituting into

, we have

, where r denotes the ratio

/

/

.

.

Considering V̄s = (1 − μ)psĪs/c, we obtain the mutant frequency , which is the same as the mutant frequency in the model without hepatocyte proliferation. It should be noted that although the mutant frequency is the same as that in the model without hepatocyte proliferation, the steady states of wild-type and resistant virus are not necessarily the same as the previous ones. They depend on ρT, ρs, ρr, and other parameters.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. Fact sheet No 164. Revised June 2011. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/index.html.

- 2.Foster GR. Past, present, and future hepatitis C treatments. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24(Suppl 2):97–104. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Rustgi V, Hoefs J, Gordon SC, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1493–1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fusco DN, Chung RT. Novel therapies for hepatitis C: insights from the structure of the virus. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:373–387. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042010-085715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dore GJ, Matthews GV, Rockstroh J. Future of hepatitis C therapy: development of direct-acting antivirals. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:508–513. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834b87f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jazwinski AB, Muir AJ. Direct-acting antiviral medications for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:154–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamarre D, Anderson PC, Bailey M, Beaulieu P, Bolger G, et al. An NS3 protease inhibitor with antiviral effects in humans infected with hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2003;426:186–189. doi: 10.1038/nature02099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanwolleghem T, Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, Roskams T, De Vos R, et al. Ultra-rapid cardiotoxicity of the hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor BILN 2061 in the urokinase-type plasminogen activator mouse. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1144–1155. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarrazin C, Rouzier R, Wagner F, Forestier N, Larrey D, et al. SCH 503034, a novel hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor, plus pegylated interferon alpha-2b for genotype 1 nonresponders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1270–1278. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin K, Perni RB, Kwong AD, Lin C. VX-950, a novel hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3-4A protease inhibitor, exhibits potent antiviral activities in HCV replicon cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1813–1822. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1813-1822.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perni RB, Almquist SJ, Byrn RA, Chandorkar G, Chaturvedi PR, et al. Preclinical profile of VX-950, a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3-4A serine protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:899–909. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.3.899-909.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reesink HW, Zeuzem S, Weegink CJ, Forestier N, van Vliet A, et al. Rapid decline of viral RNA in hepatitis C patients treated with VX-950: a phase Ib, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:997–1002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hezode C, Forestier N, Dusheiko G, Ferenci P, Pol S, et al. Telaprevir and peginterferon with or without ribavirin for chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1839–1850. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski M, et al. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1827–1838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, Nelson DR, Sulkowski MS, et al. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1014–1024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poordad F, McCone JJ, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus population dynamics during infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;299:261–284. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26397-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin C, Gates CA, Rao BG, Brennan DL, Fulghum JR, et al. In vitro studies of cross-resistance mutations against two hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitors, VX-950 and BILN 2061. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36784–36791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu L, Pilot-Matias TJ, Stewart KD, Randolph JT, Pithawalla R, et al. Mutations conferring resistance to a potent hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitor in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2260–2266. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2260-2266.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong X, Chase R, Skelton A, Chen T, Wright-Minogue J, et al. Identification and analysis of fitness of resistance mutations against the HCV protease inhibitor SCH 503034. Antiviral Res. 2006;70:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarrazin C, Kieffer TL, Bartels D, Hanzelka B, Muh U, et al. Dynamic hepatitis C virus genotypic and phenotypic changes in patients treated with the protease inhibitor telaprevir. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1767–1777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forestier N, Reesink HW, Weegink CJ, McNair L, Kieffer TL, et al. Antiviral activity of telaprevir (VX-950) and peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46:640–648. doi: 10.1002/hep.21774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kieffer TL, Sarrazin C, Miller JS, Welker MW, Forestier N, et al. Telaprevir and pegylated interferon-alpha-2a inhibit wild-type and resistant genotype 1 hepatitis C virus replication in patients. Hepatology. 2007;46:631–639. doi: 10.1002/hep.21781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rong L, Dahari H, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS. Rapid emergence of protease inhibitor resistance in hepatitis C virus. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:30ra32. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science. 1998;282:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, Roccasecca RM, Acali S, et al. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. Embo J. 2002;21:5017–5025. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM, Syder AJ, Panis M, et al. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature. 2007;446:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nature05654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ploss A, Evans MJ, Gaysinskaya VA, Panis M, You H, et al. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature. 2009;457:882–886. doi: 10.1038/nature07684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger D, Wolk B, Gosert R, Bianchi L, Blum HE, et al. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J Virol. 2002;76:5974–5984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5974-5984.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartenschlager R, Frese M, Pietschmann T. Novel insights into hepatitis C virus replication and persistence. Adv Virus Res. 2004;63:71–180. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(04)63002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Domingo E. Biological significance of viral quasispecies. Viral Hepatitis Rev. 1996;2:247–261. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, et al. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103–107. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rong L, Feng Z, Perelson AS. Emergence of HIV-1 drug resistance during antiretroviral treatment. Bull Math Biol. 2007;69:2027–2060. doi: 10.1007/s11538-007-9203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartels DJ, Zhou Y, Zhang EZ, Marcial M, Byrn RA, et al. Natural prevalence of hepatitis C virus variants with decreased sensitivity to NS3.4A protease inhibitors in treatment-naive subjects. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:800–807. doi: 10.1086/591141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillespie J. Population Genetics: A Concise Guide. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu H, Herrmann E, Reesink H, Forestier N, Weegink C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of VX-950, and its effect on hepatitis C viral dynamics. Hepatology. 2005;42(Suppl 1):S694. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen L, Peterson S, Sedaghat AR, McMahon MA, Callender M, et al. Dose-response curve slope sets class-specific limits on inhibitory potential of anti-HIV drugs. Nat Med. 2008;14:762–766. doi: 10.1038/nm1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khunvichai A, Chu H, Garg V, McHutchison J, Lawitz E, et al. Predicting HCV treatment duration with an HCV protease inhibitor co-administered with PEG-IFN/RBV by modeling both wild-type virus and low level resistant variant dynamics. Digestive Disease Week; Washington DC. May 19–24, 2007.2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y, Bartels DJ, Hanzelka BL, Muh U, Wei Y, et al. Phenotypic characterization of resistant Val36 variants of hepatitis C virus NS3-4A serine protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:110–120. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00863-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michalopoulos GK, DeFrances MC. Liver regeneration. Science. 1997;276:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dahari H, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS. Triphasic decline of hepatitis C virus RNA during antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2007;46:16–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.21657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reluga TC, Dahari H, Perelson AS. Analysis of hepatitis C virus infection models with hepatocyte homeostasis. SIAM J Appl Math. 2009;69:999–1023. doi: 10.1137/080714579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adiwijaya BS, Herrmann E, Hare B, Kieffer T, Lin C, et al. A multi-variant, viral dynamic model of genotype 1 HCV to assess the in vivo evolution of protease-inhibitor resistant variants. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elahi E, Ronaghi M. Pyrosequencing: a tool for DNA sequencing analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;255:211–219. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-752-1:211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foy E, Li K, Wang C, Sumpter JR, Ikeda M, et al. Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science. 2003;300:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1082604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, et al. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;437:1167–1172. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Li MY. Mathematical analysis of the global dynamics of a model for HIV infection of CD4+ T cells. Math Biosci. 2006;200:44–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Leenheer P, Pilyugin SS. Multistrain virus dynamics with mutations: a global analysis. Math Med Biol. 2008;25:285–322. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqn023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duffy S, Shackelton LA, Holmes EC. Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: patterns and determinants. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:267–276. doi: 10.1038/nrg2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powdrill MH, Tchesnokov EP, Kozak RA, Russell RS, Martin R, et al. Contribution of a mutational bias in hepatitis C virus replication to the genetic barrier in the development of drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20509–20513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105797108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanjuan R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R. Viral mutation rates. J Virol. 2010;84:9733–9748. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00694-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soriano V, Perelson AS, Zoulim F. Why are there different dynamics in the selection of drug resistance in HIV and hepatitis B and C viruses? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McPhee F, Hernandez D, Zhai G, Friborg J, Yu F, et al. Pre-existence of substitutions conferring resistance to HCV NS3 protease inhibitors. 1st International Workshop on Hepatitis C Resistance and New Compounds; Boston, MA. October 25–26, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cubero M, Esteban JI, Otero T, Sauleda S, Bes M, et al. Naturally occurring NS3-protease-inhibitor resistant mutant A156T in the liver of an untreated chronic hepatitis C patient. Virology. 2008;370:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Handel A, Regoes RR, Antia R. The role of compensatory mutations in the emergence of drug resistance. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yi M, Tong X, Skelton A, Chase R, Chen T, et al. Mutations conferring resistance to SCH6, a novel hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitor. Reduced RNA replication fitness and partial rescue by second-site mutations. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8205–8215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Pawlotsky JM, Benhamou Y. Chronic hepatitis B: preventing, detecting, and managing viral resistance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeni PG, Hammer SM, Carpenter CC, Cooper DA, Fischl MA, et al. Antiretroviral treatment for adult HIV infection in 2002: updated recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2002;288:222–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCown MF, Rajyaguru S, Le Pogam S, Ali S, Jiang WR, et al. The hepatitis C virus replicon presents a higher barrier to resistance to nucleoside analogs than to nonnucleoside polymerase or protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1604–1612. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01317-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wyles DL, Kaihara KA, Schooley RT. Synergy of a hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS4A antagonist in combination with HCV protease and polymerase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1862–1864. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01208-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]