Abstract

Precision is the ultimate aim of stereotactic technique. Demands on stereotactic precision reach a pinnacle in stereotactic functional neurosurgery. Pitfalls are best avoided by possessing in-depth knowledge of the techniques employed and the equipment used. The engineering principles of arc-centered stereotactic frames maximize surgical precision at the target, irrespective of the surgical trajectory, and provide the greatest degree of surgical precision in current clinical practice. Stereotactic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides a method of visualizing intracranial structures and fiducial markers on the same image without introducing significant errors during an image fusion process. Although image distortion may potentially limit the utility of stereotactic MRI, near-complete distortion correction can be reliably achieved with modern machines. Precision is dependent on minimizing errors at every step of the stereotactic procedure. These steps are considered in turn and include frame application, image acquisition, image manipulation, surgical planning of target and trajectory, patient positioning and the surgical procedure itself. Audit is essential to monitor and improve performance in clinical practice. The level of stereotactic precision is best analyzed by routine postoperative stereotactic MRI. This allows the stereotactic and anatomical location of the intervention to be compared with the anatomy and coordinates of the intended target, avoiding significant image fusion errors.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, precision, stereotactic

INTRODUCTION

In 1906, Clarke and Horsley published a landmark paper describing a topographical method of precise navigation within the brain of an experimental animal.[10] Their mechanical frame allowed precise delivery of a probe to deep-seated structures in 1-mm steps in all three planes. This powerful tool was initially hampered by the lack of in vivo imaging that could visualize relevant anatomy within the stereotactic space defined by the frame. Punctate electrolytic lesions were created to mark the locations of unipolar or bipolar stimulation sites. The observed physiological responses were then linked with the precise anatomical location after the animal was sacrificed some weeks later.

Since these early beginnings, numerous technological advancements have been adopted to improve accuracy and precision of stereotactic interventions. Ventriculography[14] was combined with the stereotactic technique by Spiegel and Wycis to estimate the location of specific intracranial structures in patients.[57] Various surrogate markers were then introduced in an effort to refine initial surgical targeting. These included recognition of neural firing patterns recorded with microelectrode techniques[21] as well as characteristic electrical impedance patterns recorded from the tip of a probe as it traveled through diverse brain tissues.[50,72]

Technological advances have culminated in the advent of stereotactic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a tool that permits in vivo stereotactic localization of visualized pathological and anatomical structures, both before and after the surgical intervention.

SURGICAL ACCURACY AND PRECISION

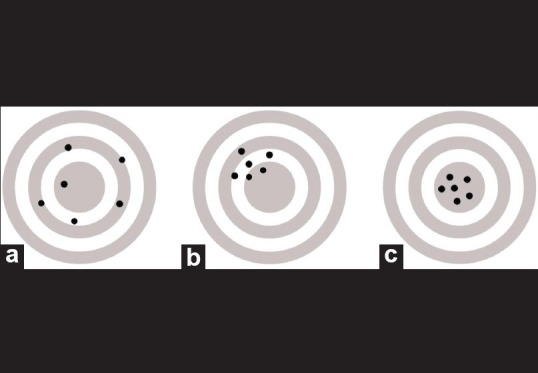

Surgical accuracy is a measure of the degree of veracity or proximity of the intervention to the intended target. Surgical precision is the degree of reproducibility or repeatability of the intervention [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of surgical accuracy and precision: (a) Accurate but not precise. (b) Precise but not accurate. (C) Accurate and precise

Specific indications demand varying levels of accuracy and precision. For instance, the level of accuracy and precision required during functional neurosurgery when targeting the sensorimotor portion of the subthalamic nucleus for Parkinson's disease is greater than that required when performing a biopsy of a large deep-seated lesion. Nevertheless, many of the principles that assist in improving precision and avoiding complications are relevant to any form of stereotactic surgery.

PREPARATION IS KEY

Pitfalls are defined as hidden or unsuspected dangers or difficulties. They are best avoided by considering known factors that may lead to potential problems. A thorough knowledge of clinical presentation, medical history, risk factors, and results of investigations, as well as an in-depth knowledge of the possible benefits and hazards of surgery are essential when considering patient selection.

Despite their relatively low incidence, hemorrhagic complications carry by far the highest risk of devastating neurological outcome in functional neurosurgery. Self-medication with aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may not be disclosed unless the physician asks specifically about their use.[64] Age and a history of hypertension are associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage in functional neurosurgery.[69]

As with other surgical procedures, patient selection and perioperative management play a crucial role in avoiding complications. However, this work focuses on the technical aspects of ensuring precision during a stereotactic procedure. The most reliable way of avoiding potential pitfalls is by having a surgeon who understands the basic principles of the technique and is confident with the equipment being used.

ENGINEERING PRINCIPLES OF STEREOTACTIC SYSTEMS

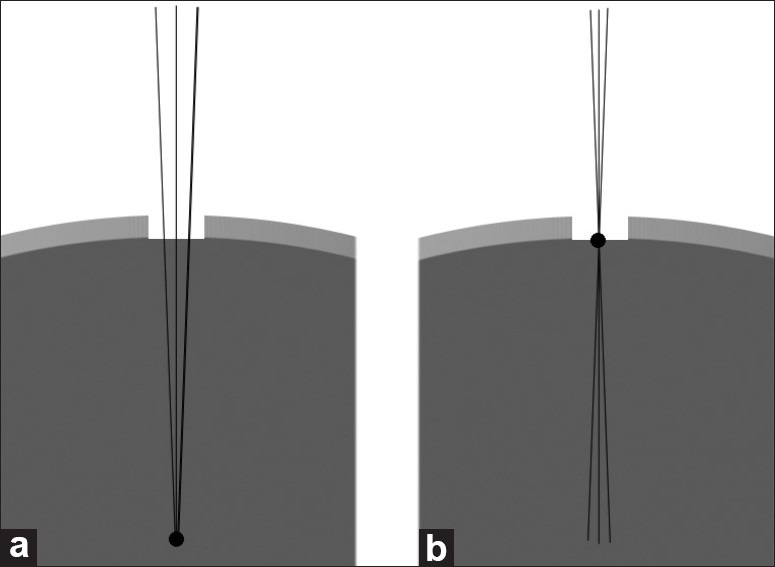

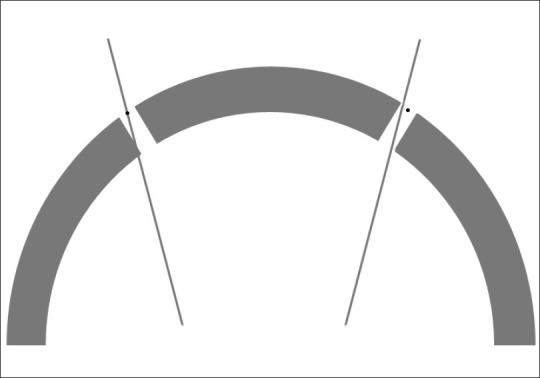

Contemporary stereotactic frames are based on the arc-centered principle that tends to maximize surgical precision at the target, irrespective of the surgical trajectory. Mini-frame or frameless navigation enjoys maximum precision at the entry point and then endeavors to replicate the planned virtual trajectory during surgery. However, small errors in trajectory can translate into significant errors at the target level [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

(a) The engineering principles of the arc-centred frame tend to maximise accuracy and precision at the target, irrespective of the surgical trajectory. (b) The engineering principles of mini-frame or frameless navigation maximise precision and accuracy at the entry point. Errors between planned and actual trajectory during surgery can result in significant errors at the target level

An early study comparing the accuracy of frame-based with frameless techniques did not find any significant difference between frame-based and mini-frame techniques. However, error calculations were based on “fused” images, introducing errors that render the methodology inappropriate in making such a comparison (see section on image fusion below).[27]

In a subsequent well-designed study from Lund, the stereotactic targeting error during thalamic deep brain stimulation (DBS) was significantly greater with mini-frame than with frame-based technique (2.5 ± 1.4 mm vs. 1.2 ± 0.6, P < 0.05–0.001).[6] Nevertheless, tremor reduction was similar at follow-up, irrespective of the implantation technique. The apparent dissociation between stereotactic accuracy and clinical outcome may be due to the inability to visualize the motor thalamus on preoperative imaging (i.e. superimposed anatomical variability) and the relatively large size of the motor thalamus that makes it more lenient to inaccuracies of targeting.

Given the greater accuracy and precision of frame-based techniques, this work focuses on frame-based surgery. However, many aspects are also applicable to other forms of stereotactic surgery.

Surgical robots allow precise, deliberate, and spatially encoded movement; in essence, they are stereotactic instruments with the potential of achieving high levels of accuracy.[19,40] Although surgical robots are not widely used in neurosurgical practice, their use is likely to increase over the coming decades. Precision in stereotactic radiosurgery also requires consideration of radiobiology and is outside the scope of this work.

ATTENTION TO DETAIL

Stereotactic surgery demands meticulous attention to detail during every step of the procedure.

Equipment

The surgeon should be familiar with the stereotactic system being used and knowledgeable about its strengths and weaknesses. Equipment should be checked prior to commencing a stereotactic procedure – a loose screw may result in geometrical inaccuracy that may compromise both the procedure and patient. As with any precision instrument, the stereotactic system requires regular maintenance and quality checks.

Frame/fiducial fixation

The stereotactic frame should be firmly secured to the skull to avoid any movement between image acquisition and surgery. Any such movement would result in targeting errors. A more perilous scenario would be if the head were to “slip” out of the fixation pins in the presence of an intracranial probe. On the other hand, overzealous tightening of pins should be avoided as this may result in penetration of the inner table of the skull and damage to intracranial structures.[5] Use of a torque wrench may assist in frame fixation.[29]

Due consideration should be give to the surgical trajectory and the frame placed such that the securing pins will not obstruct the surgical field. Particular consideration should be given when working with high-field MR machines and insulated posts should be used to prevent overheating of pin sites during imaging.

Image acquisition

“In clinical practice, brain imaging can now be divided in two parts: the diagnostic neuroradiology and the preoperative stereotactic localisation procedure. The latter is part of the therapeutic procedure. It is the surgeon's responsibility and should be closely integrated with the operation.”

Lars Leksell (1907–1986), 1985)[36]

The surgeon should supervise acquisition of stereotactic images. Thin-slice contiguous images through the target are required using a modality that allows optimal localization of the planned target. The use of contrast media will highlight vessels that can then be avoided during surgical planning. Rare instances of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm have been reported following stereotactic procedures.[48]

An effort should be made to ensure that the axes of the frame are in line with those of the scanner. A small spirit level will assist alignment of the frame axes with the scanning plane and will ensure that frame geometry is reproduced accurately on cross-sectional imaging. This is particularly important if the surgeon is relying upon manual calculation of target coordinates.

When obtaining a stereotactic MRI, the target region should be centered within the bore of the magnet since this is the region where MR distortion is the least. The field of view should include all the required fiducial markers and imaging should cover the intended entry point and target. Thin-slice contiguous imaging from entry point to target is also desirable.

MRI sequences designed for visualization of specific targets allow direct localization of anatomical structures. T2-weighted images may be used to visualize the subthalamic nucleus[24] and modified proton-density images to visualize the globus pallidus.[25] Collaboration between neurosurgeon and neuroradiology teams resulting in optimal MRI sequences that better visualize the relevant anatomy is time well spent.

Geometric distortion and MRI-guided surgery

Unlike diagnostic radiology, imaging for stereotactic surgery requires more than just visualization of structures. Although computed tomography (CT) imaging does not suffer from image distortion, anatomical detail is lacking in comparison with MRI. Inhomogeneities of the magnetic field within MR scanners can lead to geometric distortion of the acquired images.[61] Inaccurate spatial representation would render images useless for the purpose of accurate surgical targeting. Geometric accuracy at the center of the MRI field tends to be excellent; however, distortion is exacerbated at the field periphery.

A number of methods for correction of field inhomogeneities have been described.[8,60,62] Manufacturers of modern MR scanners now incorporate software solutions that correct for distortion, resulting in greatly improved geometric accuracy of MR images. Phantom experiments at our institution have revealed that despite applying distortion correction algorithms, the MR image of the anterior middle fiducial on the Leksell frame is often displayed slightly posterior to its actual location (as yet unpublished data). Manually correcting for this error during fiducial registration significantly increases registration accuracy. Larger inhomogeneities that are more difficult to correct may exist around the base of the stereotactic frame. The “base ring” of the frame should therefore be placed low down on the head. It should also be appreciated that stereotactic calculations on coronal MR images may be less reliable that those on axial images since the inferior fiducials (closest to the base ring) may suffer from greater geometric inaccuracies.

With adequate care and quality control, high fidelity stereotactic MR images offer a true geometric representation of spatial arrangement with distortion errors in the subvoxel range.[15,49,54,66] It is often stated that geometric distortion is least on 3D T1-weighted images; however, our experience is that distortion can be reduced to submillimeter values on other MRI sequences that allow visualization of anatomical structures relevant to DBS (as yet unpublished data).[24,25,26]

Image fusion – An under-recognized and significant source of targeting error

Initial attempts to circumvent problems of MR distortion relied on fusing or morphing non-stereotactic MR data onto stereotactic CT images. This idea suggested that contrast-rich MR data at the center of the field could be supplemented with accurate fiducial localization with CT at the field periphery.[2,4,31,67] Numerous commercially available software packages were developed and provide this facility. However, magnetic inhomogeneities are nonlinear whereas most fusion algorithms are linear.[35,54] In addition, fusion between CT and MR images may result in fusion errors that often go undetected. When analyzed in detail, fusion algorithms are found to introduce mean errors of between 1.2 and 1.7 mm; larger errors of close to 4.0 mm may be expected in individual patients. The magnitude of fusion errors is at least an order of magnitude above those introduced by MRI distortion.[16,43] Anatomical targeting on stereotactic MR images that visualize the fiducials and target on the same image eliminate fusion errors.

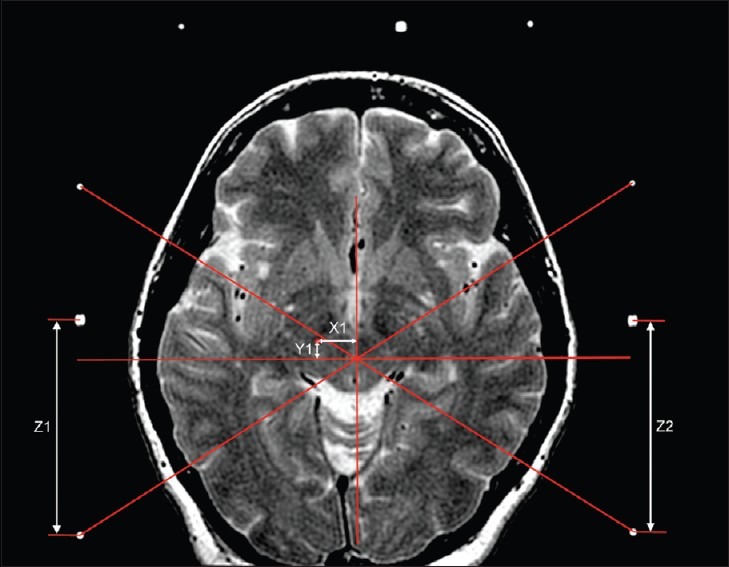

Image manipulation and registration

Some stereotactic systems allow manual calculation of the target coordinates from a selected target slice [Figure 3]. However, more detailed surgical planning will require import of the images to a dedicated software platform that allows image manipulation and precise planning of both target and trajectory. Many software platforms provide a “navigation” view rather than a standard radiological view and this should not cause confusion in laterality. Where possible, registration of fiducials should be performed on the images where the target is readily visualized as this avoids introduction of fusion errors.

Figure 3.

Manual calculation of target coordinates from axial T2 weighted image with the Leksell frame. The outer fiducials of the lateral plates form a rectangle; the diagonals of this rectangle intersect at the centre of the frame. The geometry of the frame dictates that the Z (vertical) coordinate can be determined by adding 40 mm to the distance between the posterior and middle fiducial markers on the lateral fiducial plates. X (mediolateral) and Y (anteroposterior) axes are defined by lines drawn through the frame centre and parallel to the sides of the rectangle. The geometry of the frame dictates that centre of the frame corresponds to X = 100 mm and Y = 100 mm. The X and Y coordinate of any point within the image can therefore be calculated by measuring its displacement from the centre of the frame. Lateral displacements to the left are added and displacements to the right subtracted from 100 to give the X coordinate. Anterior displacements are added to 100 and posterior displacements subtracted from 100 to give the Y coordinate. In this example, a target was selected in the right STN: Z coordinate = 40 + (Z1 + Z2)/2 mm; X coordinate = (100 − X1) mm, since the target lies to the right of the frame centre. Y coordinate = (100 + Y1) mm since the target lies anterior to the frame centre

The default on some software platforms is to minimize registration error across the volume of the acquired images. However, the aim of stereotactic surgery is to maximize accuracy at the target level. Therefore, accuracy of registration at the target slice / level is more desirable.

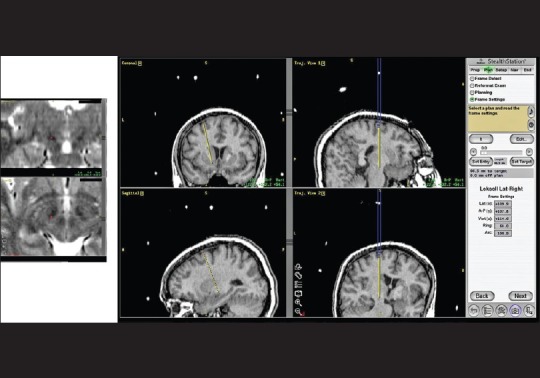

Surgical planning of the target and trajectory

A surgical trajectory that avoids sulci and ventricles has been shown to reduce the incidence of hemorrhagic complications, presumably by avoiding the enclosed vessels.[18] Planning an entry point to penetrate the crest of a gyrus is not sufficient to avoid sulci en route to the target. The individual complexity of the sulcal pattern and obliquity of the surgical trajectory require the image manipulation of the acquired stereotactic images with commercially available planning software that allows reconstruction along the proposed trajectory. Entry through the crest of a gyrus also prevents excessive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) loss when opening the dura during surgery.

Moreover, avoiding relatively stiff anatomical barriers, such as the pia and ependyma, minimizes brain displacement by the advancing probe, thus improving surgical accuracy [Figure 4].[70]

Figure 4.

In this example, the left subthalamic nucleus was targeted on T2 weighted stereotactic MRI (inset left). Stereotactic T1 volumetric images allowed selection of the entry point in the ipsilateral, pericoronal region right): Coronal and sagittal images are not sufficient to confirm avoidance of sulci and ventricles (left panel); this is best achieved by reformatting of the images in line with the planned trajectory (middle panel). The final target coordinates, together with the arc and ring angles then define the surgical trajectory (right). It should be noted that, prior to surgical planning, the fiducials were registered on the T2-weighted stereotactic MRI to avoid fusion errors during target selection. The entry point was selected on the basis of the volumetric T1 images fused to the T2 images and is therefore susceptible to errors of image fusion. However, inaccuracies are of less clinical relevance at the entry point than at the target point

Incursion into sulcus or ventricle can often be avoided by reconsideration of the planned entry point and, when performing DBS, can maximize the number of lead contacts within the target structure.

When considering stereotactic approaches to the brainstem, transgression of pial, ependymal, or tentorial surfaces can be avoided by considering ipsilateral transfrontal[33] as well as contralateral transfrontal entry points; the latter allows access to more laterally placed pontine lesions.[3] Both approaches allow the patient to remain supine during surgery, in a similar position to that in which images are traditionally acquired, thus preventing error due to positional brain shift. The transtentorial route has been virtually abandoned because of the increased risk of hemorrhage and trajectory deviation. The suboccipital transcerebellar approach is often used to access brainstem lesions.[1,11,22,38,42,53,58] Care must be taken to ensure that the frame is placed low enough to allow the lesion to be visualized and to physically allow the required trajectory with a particular frame.[42] Semi-recumbent, lateral, and prone positions have been described to provide access, some of which may limit the possibility of surgery under local anesthesia. The suboccipital approach provides the shortest distance to the brainstem target.[42,58]

When performing biopsy of a partially solid, partially cystic lesion, the solid portion should be targeted first to prevent targeting errors that would occur with significant brain shift after cyst aspiration.

The author uses a simple proforma to record the target coordinates and the “arc” and “angle” of the trajectory. The target coordinates obtained from manual calculations may be compared to those obtained from the planning station. This process offers a measure of redundancy and reduces errors in the transcription of coordinates. Some groups use a checklist in an attempt to standardize the procedure.[12]

Patient positioning

As with other forms of surgery, patient positioning is a vital part of the surgical procedure. Performing surgery in a similar position to that adopted during image acquisition may limit shift by minimizing postural movement of intracranial structures.[52] When using a pericoronal approach, patients are positioned supine with slight head-up (around 15°) to encourage venous drainage, instead of a more upright semi-sitting position.[39] A supine position is also likely to minimize the incidence of air embolism – a particular concern when patients are undergoing surgery awake without the raised central venous pressure afforded by the positive airway pressures of an intubated ventilated patient.[7,28,34,41]

Rather than being fixed to the operating table with a Mayfield clamp, head and frame may be supported by a sand-filled vacuum pillow. In the event of an intraoperative seizure, this precludes the head being forced from the retaining pins and the resulting brain trauma by an indwelling intracerebral probe.

Setting up the stereotactic equipment

Care must be taken when transferring coordinates to the frame. Some stereotactic systems provide a phantom that “double checks” the planned trajectory and coordinates (e.g. Cosman–Roberts–Wells or CRW).

Equipment essential to the procedure should be prepared and checked. Probes are assessed for any curvature that would undermine accuracy and precision. Implant and probe lengths are “marked out” according to the radius of the stereotactic system being used (e.g. 190 mm when using the Leksell frame, 160 mm when using the CRW) to ensure that the target is reached without being overshot. Equipment used for physiological monitoring (impedance, microelectrode recording) is tested.

After the coordinates are transferred to the frame, it is prudent to double check coordinates, ring, arc, and platform depth, and to perform a “reality check” on the patient to ensure that the planned trajectory and target are appropriate. When the entry point and trajectory have not been defined by the stereotactic plan, it is important to clearly mark the intended entry point on the scalp before draping to ensure that the entry point avoids eloquent cortex and venous sinuses.

Extradural surgical procedure

When a precise entry point has been planned, the surgical trajectory is re-established at each anatomical layer. A twist drill directed by the frame is sometimes employed when trephining the skull. However, a standard 14-mm burr hole provides access for hemostasis on the dura and the underlying pia and avoids transmission of excessive force to the frame. When not using the frame to direct the drill, it should be noted that when held perpendicular to the skull, the drill axis is often different from that of the planned trajectory. This should be taken into account to ensure that the final probe trajectory avoids the bony margins of the burr hole [Figure 5]. Application of bone wax to the margins of the burr hole prevents air embolism and bleeding from bone.

Figure 5.

On the left of the figure the intended trajectory has been marked on the outer table of the skull (small black dot) and the “burrhole” centred on this point. This method does not take into account that the burrhole trajectory is orthogonal to the outer table and differs to the planned trajectory. As a result, the edge of the inner table obstructs the intended trajectory. On the right of the figure, the burrhole was placed slightly lateral to the intended trajectory (small black dot). This adjustment allows the planned trajectory to traverse the burrhole unimpeded by both outer and inner bone margins

Minimizing brain shift

Accurate stereotactic targeting does not necessarily result in accurate anatomical targeting. Brain shift or “brain sinking” has often been considered an obstacle to reliable neuronavigation based on preoperative images.[65] Brain shift may be caused by CSF loss and pneumocephalus, postural movement of intracranial structures under the effect of gravity, or brain deformation due to the advancing electrode. A few millimeters of brain movement at the target region can adversely affect the targeting accuracy and the surgical intervention.

Up to 5.7 mm of subcortical shift has been reported during DBS procedures, predominantly in the direction of gravity.[17,30] In one extreme example of brain shift during attempted DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN), the authors noted that the final lead locations: “were displaced in two patients … in the genu of the internal capsule … at the border of the internal and external globus pallidum; this was probably caused by brain shift due to a perioperative subdural accumulation of air after CSF leakage through the burr hole.”[56] This degree of brain shift requires compensatory intraoperative adjustments and introduces added complication to the process of stereotactic targeting.

A number of surgical practices may be expected to reduce or avoid brain shift. Reducing CSF loss and pneumocephalus can be accomplished by the following: minimizing the time from dural opening to final DBS electrode implantation, flooding the burr hole with saline irrigation after dural opening,[45] avoiding CSF suction,[46] and sealing the dural defect (e.g. with fibrin glue) as soon as it is practical.[68] Such measures can greatly reduce brain shift of subcortical structures in the vast majority of cases.[47]

Intradural surgical procedure

The dural opening should ensure that the trajectory avoids the margins of the burr hole and should be large enough to admit the stereotactic probe whilst being small enough to prevent excessive CSF loss. The underlying pia is opened sharply and hemostasis secured before the probe is advanced into the brain parenchyma.

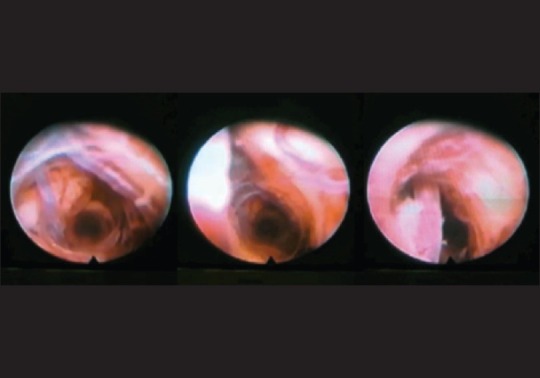

A sharp tip probe would theoretically result in less brain deformation; however, the authors favor a blunt tip probe in view of potential penetration, rather than displacement, of intraparenchymal vessels and the resulting hemorrhage [Figure 6]. Twirling movements while advancing the probe will result in a corkscrew action and greater trauma to the brain parenchyma if the probe is not perfectly straight. A smooth, steady advancement will allow displacement rather than rupture of any vessels encountered by the advancing blunt tip.

Figure 6.

Blunt probes tend to displace rather than rupture blood vessels crossing the surgical trajectory. These still shots are from an endoscopic video recorded during extraction of a small, 3 mm diameter blunt- tip endoscope from the brain. The left panel demonstrates the parenchyma and vessels in the distal brain track without evidence of haemorrhage. On the middle panel, a larger calibre vessel (arteriole) appears out of focus on the left side of the picture as the endoscope is withdrawn. The right panel confirms that the aforementioned vessel was in the path of the probe. The vessel had clearly been pushed aside by the advancing probe without damage or penetration causing haemorrhage (video courtesy of Prof Marwan Hariz)

After the dura has been opened, high-flow saline irrigation and sealing of the defect with fibrin glue (Tisseel VH Fibrin Sealant, Baxter AG) will prevent excessive CSF egress – an important consideration when performing bilateral surgery.

Brain mapping in functional neurosurgery

Microelectrode recording (MER) is currently the most commonly used technique for physiological brain mapping. Despite the lack of available evidence that this approach improves clinical outcome, many groups believe that the target should be identified physiologically with MER. Some authors have suggested that the presence of brain shift demands the use of surrogate markers during precision stereotactic surgery in order to adjust for stereotactic and anatomical targeting errors.[13,23,44] However, one must consider that it may be the mapping process itself that exacerbates brain shift since the use of multiple tracks, prolonged recording, or stimulation time would tend to increase CSF loss if adequate sealing of the burr hole is not achieved. In addition, surrogate markers of anatomical location may sometimes be misleading.[51,55,63]

Some authors avoid brain mapping in favor of an MRI-guided and MRI-verified approach that minimizes brain shift;[20,26,45,69] others have approached this challenge by using intraoperative MRI to guide targeting after burr hole placement and brain slump has occurred.[37,59] Results of open-labeled series suggest that such an image-verified approach to surgery is likely to be as effective as other approaches.[9,20,32] Conversely, the meticulous use of neuroimaging – both in planning the trajectory and for immediate postoperative verification of targeting accuracy – appears to carry a significantly lower risk of hemorrhage and associated permanent deficit.[69]

AUDITING ACCURACY AND PRECISION

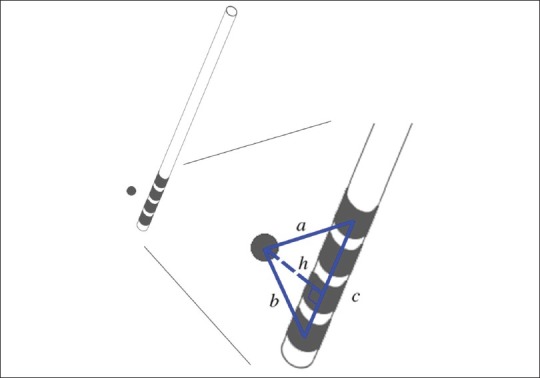

Postoperative stereotactic imaging best documents the accuracy and precision of an intervention – this allows a comparison of the intended target coordinates with the actual target coordinates of the surgical intervention [Figure 7]. Systematic targeting errors can be recognized and strategies adopted to significantly improve the precision and accuracy of subsequent procedures.[26] Stereotactic fluoroscopy is often employed in theater to ensure that the probe has reached the intended target. Other groups perform stereotactic CT. However, only stereotactic MRI can assess whether the probe has reached the intended stereotactic and anatomical target.[20] Acquired stereotactic coordinates of the surgical intervention can direct the single additional pass necessary for any relocation, thus minimizing the number of brain passes required to reach the intended target.[69]

Figure 7.

Calculation of the stereotactic targeting error in a DBS procedure: the planned target point is shown in relation to the actual quadripolar lead location. The centres of the deepest and most superficial DBS contact and the intended target point form a triangle in space (depicted in blue with sides a, b and c). The perpendicular distance between planned target point and electrode trajectory (h) is defined as the stereotactic targeting error

Safety is a concern when performing MRI in the presence of implanted DBS hardware and neurosurgeons should liaise closely with radiology and MR physicist colleagues to establish local practices and monitoring of MRI events. They should also be aware of the reality that the number of reported adverse neurological events in such situations is extremely low when sensible precautions are taken and many thousands of MRI scans have been obtained with implanted MRI hardware without adverse consequences.[71]

IMMEDIATE RETARGETING

Imprecision of stereotactic targeting can be rectified immediately since the frame can be used to guide an additional brain pass. The previous stereotactic coordinates are modified according to the observed targeting error. Extension of the initial dural opening will allow a new corticotomy a few millimeters away from the first in the direction of the targeting error. This approach avoids the trajectory of the new track crossing that of the old and results in correction of suboptimal targeting.

CONCLUSION

Numerous stereotactic systems are currently used in clinical practice and a variety of intra-procedural techniques are employed with the aim of improving safety and precision of the surgical procedure. Comprehensive clinical assessment, appropriate patient selection, purposeful stereotactic visualization of the brain target, meticulous calculation of coordinates and trajectory, and a surgical team that is familiar with the basic principles of the techniques being employed are essential in avoiding pitfalls. Routine acquisition of postoperative stereotactic imaging documents the actual location of the surgical procedure and allows comparison with the intended target. Meticulous audit of the results will allow incremental improvement in the accuracy and precision of stereotactic surgery.

Publication of this manuscript has been made possible by an educational grant from

ELEKTA

ELEKTA

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The authors of this paper have received no outside funding, and have nothing to disclose.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2012/3/2/53/91612

REFERENCES

- 1.Abernathey CD, Camacho A, Kelly PJ. Stereotaxic suboccipital transcerebellar biopsy of pontine mass lesions. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:195–200. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.2.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander E, 3rd, Kooy HM, van Herk M, Schwartz M, Barnes PD, Tarbell N, et al. Magnetic resonance image-directed stereotactic neurosurgery: Use of image fusion with computerized tomography to enhance spatial accuracy. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:271–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amundson EW, McGirt MJ, Olivi A. A contralateral, transfrontal, extraventricular approach to stereotactic brainstem biopsy procedures. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:565–70. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.3.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz TZ, Nandi D, Parkin S, Liu X, Giladi N, Bain P, et al. Targeting the subthalamic nucleus. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2001;77:87–90. doi: 10.1159/000064602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakay R, Smith A. Deep brain stimulation: Complications and attempts at avoiding them. Open Neurosurg J. 2011;4(Suppl 1-M4):42–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjartmarz H, Rehncrona S. Comparison of accuracy and precision between frame-based and frameless stereotactic navigation for deep brain stimulation electrode implantation. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2007;85:235–42. doi: 10.1159/000103262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang EF, Cheng JS, Richardson RM, Lee C, Starr PA, Larson PS. Incidence and management of venous air embolisms during awake deep brain stimulation surgery in a large clinical series. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2011;89:76–82. doi: 10.1159/000323335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang H, Fitzpatrick JM. A technique for accurate magnetic resonance imaging in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1992;11:319–29. doi: 10.1109/42.158935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cif L, Vasques X, Gonzalez V, Ravel P, Biolsi B, Collod-Beroud G, et al. Long-term follow-up of DYT1 dystonia patients treated by deep brain stimulation: An open-label study. Mov Disord. 2010;25:289–99. doi: 10.1002/mds.22802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke RH, Horsley V. On a method of investigating the deep ganglia and tracts of the central nervous system (cerebellum) BMJ. 1906;2:1799–800. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31814d4d99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffey RJ, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic surgery for mass lesions of the midbrain and pons. Neurosurgery. 1985;17:12–8. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly PJ, Kilpatrick M, Jaggi JL, Church E, Baltuch GH. Feasibility of an operational standardized checklist for movement disorder surgery.A pilot study. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87:94–100. doi: 10.1159/000202975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuny E, Guehl D, Burbaud P, Gross C, Dousset V, Rougier A. Lack of agreement between direct magnetic resonance imaging and statistical determination of a subthalamic target: The role of electrophysiological guidance. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:591–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.3.0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dandy WE. Ventriculography following the injection of air into the cerebral ventricles. Ann Surg. 1918;68:5–11. doi: 10.1097/00000658-191807000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doran SJ, Charles-Edwards L, Reinsberg SA, Leach MO. A complete distortion correction for MR images: I.Gradient warp correction. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:1343–61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/7/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffner F, Schiffbauer H, Breit S, Friese S, Freudenstein D. Relevance of image fusion for target point determination in functional neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:445–51. doi: 10.1007/s007010200065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias WJ, Fu KM, Frysinger RC. Cortical and subcortical brain shift during stereotactic procedures. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:983–8. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/11/0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias WJ, Sansur CA, Frysinger RC. Sulcal and ventricular trajectories in stereotactic surgery. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:201–7. doi: 10.3171/2008.7.17625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eljamel MS. Robotic neurological surgery applications: Accuracy and consistency or pure fantasy? Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87:88–93. doi: 10.1159/000202974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foltynie T, Zrinzo L, Martinez-Torres I, Tripoliti E, Petersen E, Holl E, et al. MRI-guided STN DBS in Parkinson's disease without microelectrode recording: Efficacy and safety. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:358–63. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.205542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guiot G, Hardy J, Albe-Fessard D. [Precise delimitation of the subcortical structures and identification of thalamic nuclei in man by stereotactic electrophysiology.] Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1962;5:1–18. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1095441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guthrie BL, Steinberg GK, Adler JR. Posterior fossa stereotaxic biopsy using the Brown-Roberts-Wells stereotaxic system.Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:649–52. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.4.0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halpern CH, Danish SF, Baltuch GH, Jaggi JL. Brain shift during deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson's disease. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86:37–43. doi: 10.1159/000108587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hariz MI, Krack P, Melvill R, Jorgensen JV, Hamel W, Hirabayashi H, et al. A quick and universal method for stereotactic visualization of the subthalamic nucleus before and after implantation of deep brain stimulation electrodes. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2003;80:96–101. doi: 10.1159/000075167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirabayashi H, Tengvar M, Hariz MI. Stereotactic imaging of the pallidal target. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S130–4. doi: 10.1002/mds.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holl EM, Petersen EA, Foltynie T, Martinez-Torres I, Limousin P, Hariz MI, et al. Improving targeting in image-guided frame-based deep brain stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2010;67(2 Suppl Operative):437–47. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181f7422a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holloway KL, Gaede SE, Starr PA, Rosenow JM, Ramakrishnan V, Henderson JM. Frameless stereotaxy using bone fiducial markers for deep brain stimulation. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:404–13. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.3.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hooper AK, Okun MS, Foote KD, Haq IU, Fernandez HH, Hegland D, et al. Venous air embolism in deep brain stimulation. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87:25–30. doi: 10.1159/000177625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamiryo T, Jackson T, Laws E., Jr A methodology designed to increase accuracy and safety in stereotactic brain surgery. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2000;43:1–3. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan MF, Mewes K, Gross RE, Skrinjar O. Assessment of brain shift related to deep brain stimulation surgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86:44–53. doi: 10.1159/000108588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondziolka D, Dempsey PK, Lunsford LD, Kestle JR, Dolan EJ, Kanal E, et al. A comparison between magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography for stereotactic coordinate determination. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:402–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krack P. Subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson's disease: A new benchmark. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:356–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.222497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kratimenos GP, Nouby RM, Bradford R, Pell MF, Thomas DG. Image directed stereotactic surgery for brain stem lesions. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1992;116:164–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01540871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar R, Goyal V, Chauhan RS. Venous air embolism during microelectrode recording in deep brain stimulation surgery in an awake supine patient. Br J Neurosurg. 2009;23:446–8. doi: 10.1080/02688690902775538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langlois S, Desvignes M, Constans JM, Revenu M. MRI geometric distortion: A simple approach to correcting the effects of non-linear gradient fields. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:821–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199906)9:6<821::aid-jmri9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leksell L, Leksell D, Schwebel J. Stereotaxis and nuclear magnetic resonance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:14–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.48.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin AJ, Larson PS, Ostrem JL, Keith Sootsman W, Talke P, Weber OM, et al. Placement of deep brain stimulator electrodes using real-time high-field interventional magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1107–14. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathisen JR, Giunta F, Marini G, Backlund EO. Transcerebellar biopsy in the posterior fossa: 12 years experience. Surg Neurol. 1987;28:100–4. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(87)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyagi Y, Shima F, Sasaki T. Brain shift: An error factor during implantation of deep brain stimulation electrodes. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:989–97. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/11/0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathoo N, Cavusoglu MC, Vogelbaum MA, Barnett GH. In touch with robotics: Neurosurgery for the future. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:421–33. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000153929.68024.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nazzaro JM, Lyons KE, Honea RA, Mayo MS, Cook-Wiens G, Harsha A, et al. Head positioning and risk of pneumocephalus, air embolism, and hemorrhage during subthalamic deep brain stimulation surgery. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2010;152:2047–52. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0776-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neal JH, Van Norman AS. Transcerebellar biopsy of posterior fossa lesions using the Leksell gamma model stereotactic frame. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:473–4. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199303000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Gorman RL, Jarosz JM, Samuel M, Clough C, Selway RP, Ashkan K. CT/MR image fusion in the postoperative assessment of electrodes implanted for deep brain stimulation. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87:205–10. doi: 10.1159/000225973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pallavaram S, Dawant BM, Remple M, Neimat JS, Kao C, Konrad PE, et al. Effect of brain shift on the creation of functional atlases for deep brain stimulation surgery. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2010;5:221–8. doi: 10.1007/s11548-009-0391-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel NK, Plaha P, Gill SS. Magnetic resonance imaging-directed method for functional neurosurgery using implantable guide tubes. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(5 Suppl 2):358–65. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303994.89773.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel NK, Plaha P, O’Sullivan K, McCarter R, Heywood P, Gill SS. MRI directed bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1631–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.12.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersen EA, Holl EM, Martinez-Torres I, Foltynie T, Limousin P, Hariz MI, et al. Minimizing brain shift in stereotactic functional neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2010;67(3 Suppl Operative):213–21. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000380991.23444.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rayes M, Bahgat DA, Kupsky WJ, Mittal S. Middle cerebral artery pseudoaneurysm formation following stereotactic biopsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:664–8. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100009513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reinsberg SA, Doran SJ, Charles-Edwards EM, Leach MO. A complete distortion correction for MR images: II.Rectification of static-field inhomogeneities by similarity-based profile mapping. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2651–61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/11/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson BW, Bryan JS, Rosvold HE. Locating brain structures.Extensions to the impedance method. Arch Neurol. 1965;13:477–86. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1965.00470050025003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Rodriguez M, Leiva C, Rodriguez-Palmero M, Nieto J, Garcia-Garcia D, et al. Neuronal activity of the red nucleus in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:908–11. doi: 10.1002/mds.22000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rohlfing T, Maurer CR, Jr, Dean D, Maciunas RJ. Effect of changing patient position from supine to prone on the accuracy of a Brown-Roberts-Wells stereotactic head frame system. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:610–8. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000048727.65969.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roujeau T, Machado G, Garnett MR, Miquel C, Puget S, Geoerger B, et al. Stereotactic biopsy of diffuse pontine lesions in children. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(1 Suppl):1–4. doi: 10.3171/PED-07/07/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sankar T, Lozano AM. Magnetic resonance imaging distortion in functional neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2011;75:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schiff SJ, Dunagan BK, Worth RM. Failure of single-unit neuronal activity to differentiate globus pallidus internus and externus in Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:119–28. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.1.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smeding HM, Speelman JD, Koning-Haanstra M, Schuurman PR, Nijssen P, van Laar T, et al. Neuropsychological effects of bilateral STN stimulation in Parkinson disease: A controlled study. Neurology. 2006;66:1830–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234881.77830.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spiegel EA, Wycis HT, Marks M, Lee AJ. Stereotaxic Apparatus for Operations on the Human Brain. Science. 1947;106:349–50. doi: 10.1126/science.106.2754.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spiegelmann R, Friedman WA. Stereotactic suboccipital transcerebellar biopsy under local anesthesia using the Cosman-Roberts-Wells frame. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:486–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.3.0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Starr PA, Martin AJ, Ostrem JL, Talke P, Levesque N, Larson PS. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulator placement using high-field interventional magnetic resonance imaging and a skull-mounted aiming device: Technique and application accuracy. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:479–90. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.JNS081161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sumanaweera TS, Adler JR, Glover GH, Hemler PF, van den Elsen PA, Martin D, et al. Method for correcting magnetic resonance image distortion for frame-based stereotactic surgery, with preliminary results. J Image Guid Surg. 1995;1:151–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-712X(1995)1:3<151::AID-IGS4>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sumanaweera TS, Adler JR, Jr, Napel S, Glover GH. Characterization of spatial distortion in magnetic resonance imaging and its implications for stereotactic surgery. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:696–703. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199410000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sumanaweera TS, Glover GH, Binford TO, Adler JR. MR susceptibility misregistration correction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1993;12:251–9. doi: 10.1109/42.232253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Horn G, Hassenbusch SJ, Zouridakis G, Mullani NA, Wilde MC, Papanicolaou AC. Pallidotomy: A comparison of responders and nonresponders. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:263–71. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vitek JL, Bakay RA, Hashimoto T, Kaneoke Y, Mewes K, Zhang JY, et al. Microelectrode-guided pallidotomy: Technical approach and its application in medically intractable Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1998;88:1027–43. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.6.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winkler D, Tittgemeyer M, Schwarz J, Preul C, Strecker K, Meixensberger J. The first evaluation of brain shift during functional neurosurgery by deformation field analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1161–3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.047373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu C, Apuzzo ML, Zee CS, Petrovich Z. A phantom study of the geometric accuracy of computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging stereotactic localization with the Leksell stereotactic system. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:1092–8. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200105000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu C, Petrovich Z, Apuzzo ML, Luxton G. An image fusion study of the geometric accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging with the Leksell stereotactic localization system. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2001;2:42–50. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v2i1.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zonenshayn M, Sterio D, Kelly PJ, Rezai AR, Beric A. Location of the active contact within the subthalamic nucleus (STN) in the treatment of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zrinzo L, Foltynie T, Limousin P, Hariz MI. Reducing hemorrhagic complications in functional neurosurgery: A large case series and systematic literature review. J Neurosurg. 2011 Sep 9; doi: 10.3171/2011.8.JNS101407. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zrinzo L, van Hulzen AL, Gorgulho AA, Limousin P, Staal MJ, De Salles AA, et al. Avoiding the ventricle: A simple step to improve accuracy of anatomical targeting during deep brain stimulation. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:1283–90. doi: 10.3171/2008.12.JNS08885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zrinzo L, Yoshida F, Hariz MI, Thornton J, Foltynie T, Yousry TA, et al. Clinical safety of brain magnetic resonance imaging with implanted deep brain stimulation hardware: Large case series and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2011;76:164–72. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zrinzo LU, Hariz MI. Recording in Functional Neurosurgery. In: Lozano AM, Gildenberg PL, Tasker RR, editors. Textbook of stereotactic and functional neurosurgery. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2009. pp. 1325–30. [Google Scholar]