Abstract

Esophageal adenocarcinoma carries a poor prognosis. Tumor response to neoadjuvant therapy is a key prognostic factor in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, but is inconsistent. Identifying tumor characteristics that portend a favorable response to neoadjuvant therapy would be a valuable clinical tool. The anticancer actions of vitamin D and its receptor may have implications. In this study, 15 biopsy specimens were procured retrospectively from patients being treated for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. The tissue was immunostained for the vitamin D receptor and compared on the basis of response to neoadjuvant therapy. Tumors that did not respond to neoadjuvant therapy had greater expression of VDR than tumors that responded completely. Expression of VDR declined with tumor de-differentiation. The data suggest that a relationship between vitamin D receptor expression and response to neoadjuvant therapy is plausible.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Esophageal cancer, Neoadjuvant therapy, Vitamin D, Vitamin D receptor

INTRODUCTION

The prognosis for patients undergoing resection for esophageal adenocarcinoma remains poor, with reports of 5-year overall survival between 25% – 39% depending on surgical modality and the use of neoadjuvant therapy (1–4). Neoadjuvant therapy – chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or chemoradiation therapy prior to surgery – may improve 5-year survival up to 59% (5), but the outcomes vary widely and the overall benefit when considering the adverse effects of treatment is controversial (6).

Incomplete tumor resection (7) and positive lymph nodes (8) may portend poor post-operative survival. In contrast, factors predicting a positive post-operative prognosis include a complete or major response to neoadjuvant treatment (8) and complete primary tumor resection (R0 resection) (9). T stage classification, a univariate predictor of positive post-operative prognosis, is inversely related to the response to neoadjuvant treatment (8); patients with lower T stages are more likely to respond to neoadjuvant therapy and perform better post-operatively. Patients responsive to neoadjuvant treatment are also less likely to have metastatic lymph nodes (8), and are more likely to attain complete primary tumor resection, have improved 5-year survival, and fewer disease recurrences (10, 11), making the pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy a key prognostic indicator in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

However, the tumor response to neoadjuvant treatment is inconsistent. Metzger reported that 63% of patients with locally advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy showed less then 50% histopathologic regression (12). Similarly, there is less than 50% histopathologic regression in 71% of patients with locally advanced disease (13). Indeed, histopathologic tumor regression is the most significant independent prognostic indicator (14). Undoubtedly, identifying tumor characteristics and biomarkers that presage responsiveness to neoadjuvant treatment would be a valuable clinical tool.

Vitamin D is a hormone whose primary function is to control bone mineralization and calcium homeostasis in higher organisms. Vitamin D receptors (VDRs) belong to the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors and mediates the effects of the active vitamin D metabolite, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3). In epithelial cells, the VDR and its ligand, 1,25(OH)2D3, contribute to maintenance of the differentiated phenotype and promote pathways that defend cells against risk for carcinogenic conversion due to their anti-proliferative, pro-differentiation, pro-apoptotic and anti-metastatic activity (15, 16).

Substantial evidence purports a possible anticancer role for vitamin D and its signaling pathways in breast, prostate, skin and colon cancers (15, 17). Endothelial cell tumors in VDR knockout mice grow larger than in wild type mice. Furthermore, wild type mice are amenable to calcitriol-mediated tumor inhibition whereas VDR knockout mice are not (18). Additional clinical support is provided by the correlation between a single nucleotide polymorphism in the VDR gene and the risk for colon cancer in human subjects (19). In this study, biopsy tissues prior to neoadjuvant therapy from patients with adenocarcinoma were evaluated for VDR expression and the histopathological response to treatment was assessed at resection.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Tissue Specimens

Biopsy and post neoadjuvant therapy resection specimens from fifteen patients who had been treated between 2004–2009 for esophageal adenocarcinoma at the Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE, were procured retrospectively. The Creighton University Institutional Review Board approved the use of these tissues for this study. All patients received neoadjuvant therapy and subsequent surgical resection. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens were variable but most patients received 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin (Table 1). Most patients also received neoadjuvant radiation therapy (Table 1). The biopsies and resection specimens were examined and scored independently by two investigators (PS, WJH). Tumor staging prior to treatment was assessed by computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Thirteen of fifteen specimens were from T3 disease; the remaining were T2.

Table 1.

Neoadjuvant therapy regimens given to patients.

| Patient | Chemotherapy Regimen | Chemoradiation Treatment (Gy) |

Response | Overall Survival |

Disease Free Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5-FU, Epirubicin (3) | - | N | 6.40 | 1.20 |

| 2 | 5-FU, Cisplatin (2) | 4500 | N | 36.27 | 31.13 |

| 3 | 5-FU, Cisplatin | - | N | 32.43 | 15.17 |

| 4 | 5-FU, Cisplatin (2) | 4500 | N | 11.57 | 8.87 |

| 5 | 5-FU, Cisplatin (1) | - | N | 51.23 | 51.23 |

| 6 | 5-FU, Cisplatin (2) | 4500 | N | 15.83 | 12.23 |

| 7 | Cisplatin, Epirubicin (3) | - | N | 3.63 | 3.63 |

| 8 | 5-FU, Cisplatin (2) | - | N | 31.87 | 31.87 |

| 9 | 5-FU, Cisplatin | 5040 | N | 12.73 | 8.17 |

| 10 | Carboplatinum | 5040 | C | 24.77 | 24.77 |

| 11 | 5-FU, Cisplatin (2) | 4400 | C | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| 12 | 5-FU, Cisplatin, Taxol (3) | 5000 | C | 5.33 | 5.20 |

| 13 | 5-FU, Cisplatin | 5040 | C | 48.47 | 10.57 |

| 14 | Cisplatin, CPT-11 (4) | 5040 | C | 17.03 | 17.03 |

| 15 | 5-FU, Cisplatin (2) | 4500 | C | 40.73 | 40.73 |

5-FU = 5-Fluoruracil, Gy = Gray (unit), N = Non responder; C = Complete responder.

The number of chemotherapy cycles was not available these patients.

Esophageal Biopsy Specimens

Assessment of tumor differentiation on initial biopsy was performed using a three-grade classification system. Well-differentiated tumors were defined by the presence of well-formed glands containing malignant columnar cells displaying small regular nuclei. The complete absence of gland formation, or the presence of bizarrely shaped glands, identified poorly differentiated tumors. Moderately differentiated tumors possessed well-formed glands, but the cells were less columnar or frankly cuboidal, with reduced cell polarity and more dysplastic nuclei than those observed in well-differentiated tumors. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on the biopsies using anti-VDR antibody, as described below.

Esophageal Resection Specimens Following Neoadjuvant Therapy

Histopathologic examination of all resected specimens consisted of thorough evaluations of tumor stage, residual tumor (R) category, grading, and number of examined and involved lymph nodes. Specimens were grouped as complete responders (C) if there was no residual tumor remaining, assessed by pathologic examination of the resected specimen. Subjects were grouped as non-responders (N) if there was evidence of tumor in the resection specimen and if the T staging did not change or increased at postoperative assessment.

Immunofluorescence

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsy tissues were used for immunofluorescence labeling. After deparaffinization and rehydration, antigen retrieval was performed prior to immunostaining. Sections were incubated for 2 h in block/permeabilizing solutions containing PBS, 0.25% Triton X-100, and 5% (v/v) goat serum at room temperature. The slides were subsequently incubated with a primary antibody solution including mouse anti-VDR (SantaCruz Biotech, SantaCruz, CA; sc-13133) (1:200 in PBS) at 4 °C ove rnight. After washing with PBS four times for 5 min each, a secondary antibody (1:200 dilution of affinity purified goat anti-mouse cyanine 3 (cy3) antibody, PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100,1% goat serum) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Westgrove, PA) was applied to the sections for 2 h in the dark. Negative controls were run in parallel with complete omission of primary antibody. Sections were washed with PBS four times for 5 min. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). A single layer of nail polish was placed around the edge of slide to prevent escape of mounting media from the coverslip.

Analysis

Slides were visualized with a BX51 microscope, photographed with an Olympus DP71 camera using the same exposure time for each slide, and analyzed using Image J software (National Institutes of Health). Each image was opened in Image J and converted to an RGB stack. The threshold for each image was set to minimize the background fluorescence that would be incorporated into the software’s measurement of intensity. The image was then analyzed by the software. Chi-square statistical analyses, t-tests, and linear regression were used for data analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 15 biopsy tissues were included in the analysis. Characteristics of the patients of whom biopsies were taken are displayed in Table 2. Tumor characteristics and the mean VDR fluorescence intensity for each specimen are shown in Table 3. Results of the immunofluorescence staining and other post-operative outcomes are shown in Table 4. The VDR immunofluorescence was more intense in the non-responders group than the complete responders group (Table 4). The difference was even greater when moderately and well differentiated tumors (histologic grade G1 and G2) were analyzed separately from poorly differentiated tumors (Table 4). However, there was no statistically significant difference between any of the groups.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of whom tissue biopsies were taken.

| All tumor grades | Complete Responders (n=6) |

Non- responders (n=9) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 5 (83%) | 9 (100%) |

| Mean age (S.D.) | 61 (5) | 64 (9) |

| CAD | 1 (17%) | 1 (11%) |

| DM | 1 (17%) | 2 (22%) |

| HT | 5 (83%) | 6 (67%) |

| Smoker | 3 (50%) | 6 (67%) |

| Other CM | 2 (33%) | 1 (11%) |

| Grades G1, G2 | Complete Responders (n=4) |

Non- responders (n=5) |

| Male | 4 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| Mean age (S.D.) | 58 (2) | 66 (9) |

| CAD | 1 (25%) | 1 (20%) |

| DM | 1 (25%) | 1 (20%) |

| HT | 4 (100%) | 3 (60%) |

| Smoker | 2 (50%) | 3 (60%) |

| Other CM | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Grade G3 | Complete Responders (n=2) |

Non- responders (n=4) |

| Male | 1 (50%) | 4 (100%) |

| Mean age (st. dev.) | 67 (3) | 62 (9) |

| CAD | 0 | 0 |

| DM | 0 | 1 (25%) |

| HT | 1 (50%) | 3 (75%) |

| Smoker | 1 (50%) | 3 (75%) |

| Other CM | 1 (50%) | 1 (25%) |

Table 3.

Tumor characteristics and mean VDR fluorescence intensity.

| Biopsy | Grade | T | N | M | Stage | Response | R0 | Recurrence | Mean Fluorescence Intensity ± S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | N | Y | Y | 145.0 ± 35.2 |

| 2 | G2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | N | Y | Y | 137.0 ± 31.1 |

| 3 | G1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | N | Y | Y | 116.6 ± 30.5 |

| 4 | G3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | IIB | N | N | Y | 115.4 ± 35.5 |

| 5 | G2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | IIB | N | Y | N | 114.7 ± 32.6 |

| 6 | G3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | N | Y | Y | 98.2 ± 33.5 |

| 7 | G3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | N | N | N | 95.0 ± 32.6 |

| 8 | G3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | N | N | N | 85.6 ± 24.5 |

| 9 | G2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | N | Y | Y | 83.4 ± 23.6 |

| 10 | G2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | C | Y | N | 133.8 ± 38.7 |

| 11 | G2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | IIB | C | Y | N | 124.4 ± 29.6 |

| 12 | G3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | C | Y | Y | 119.7 ± 34.7 |

| 13 | G2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | IIB | C | Y | Y | 90.7 ± 29.3 |

| 14 | G3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | IB | C | Y | N | 78.0 ± 27.3 |

| 15 | G2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | IIIA | C | Y | N | 59.7 ± 19.3 |

C = complete responder; N = non-responder; G1 = well differentiated; G2 = moderately differentiated; G3 = poorly differentiated; Y= Yes; N= No

Table 4.

Immunofluorescence staining intensity of VDR and post-operative outcomes.

| All tumor grades | Complete Responders (n=6) |

Non- responders (n=9) |

|---|---|---|

| VDR IF intensity: | 101.0 ± 26.8 | 110.1 ± 20.3 |

| mean ± S.D. | ||

| R0 resection | 6 (100%) | 6 (67%) |

| Recurrence | 2 (33%) | 6 (67%) |

| Survival in | ||

| months ± S.D. | ||

| Disease Free | 17 ± 13 | 18 ± 16 |

| Overall | 23 ± 17 | 22 ± 15 |

| Grades G1, G2 | Complete Responders (n=4) |

Non- responders (n=5) |

| VDR IF intensity: | 102.1 ± 29.3 | 119.3 ± 21.4 |

| mean ± S.D. | ||

| R0 resection | 4 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| Recurrence | 1 (25%) | 4 (80%) |

| Survival in | ||

| months (S.D.) | ||

| Disease Free | 19 (15) | 21 (18) |

| Overall | 29 (18) | 28 (16) |

| Grade G3 | Complete Responders (n=2) |

Non- responders (n=4) |

| VDR IF intensity: | ||

| average of the | 98.9 (20.9) | 98.6 (10.8) |

| means (S.D.) | ||

| R0 resection | 2 (100%) | 1 (25%) |

| Recurrence | 1 (50%) | 2 (50%) |

| Survival in | ||

| months (S.D.) | ||

| Disease Free | 11 (6) | 14 (11) |

| Overall | 11 (6) | 16 (10) |

G1 = well differentiated; G2 = moderately differentiated; G3 = poorly differentiated; S.D. = standard deviation

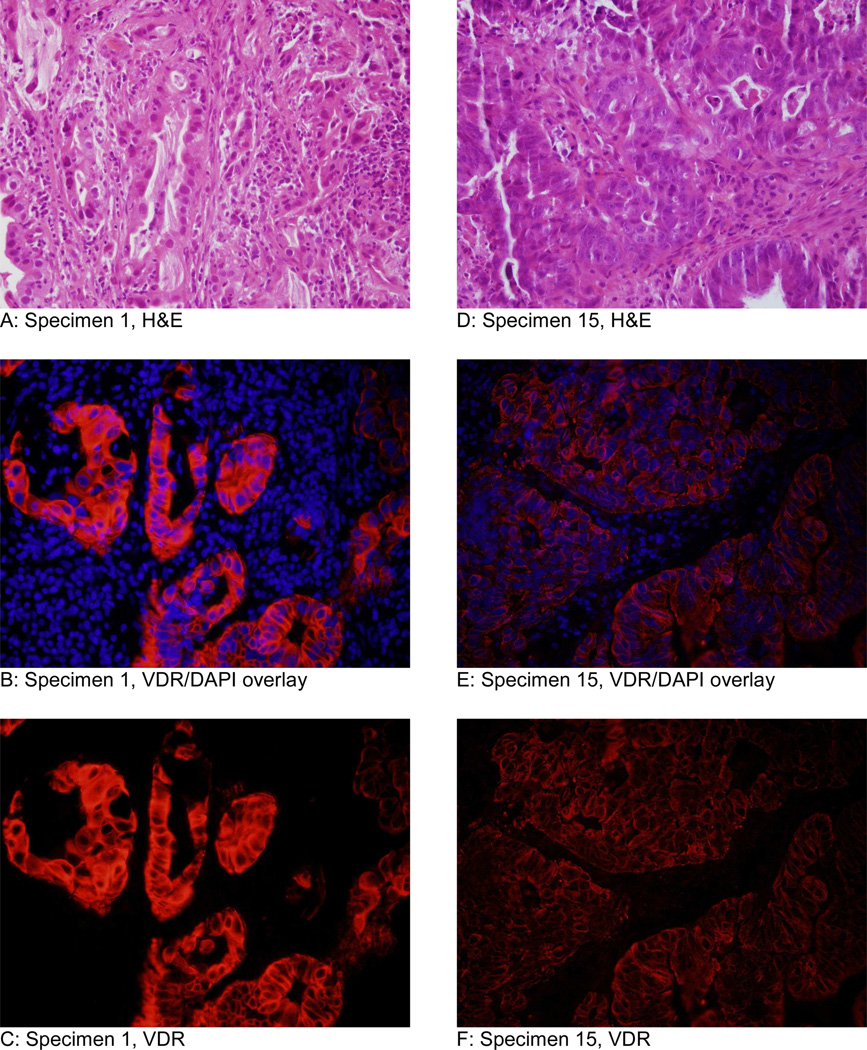

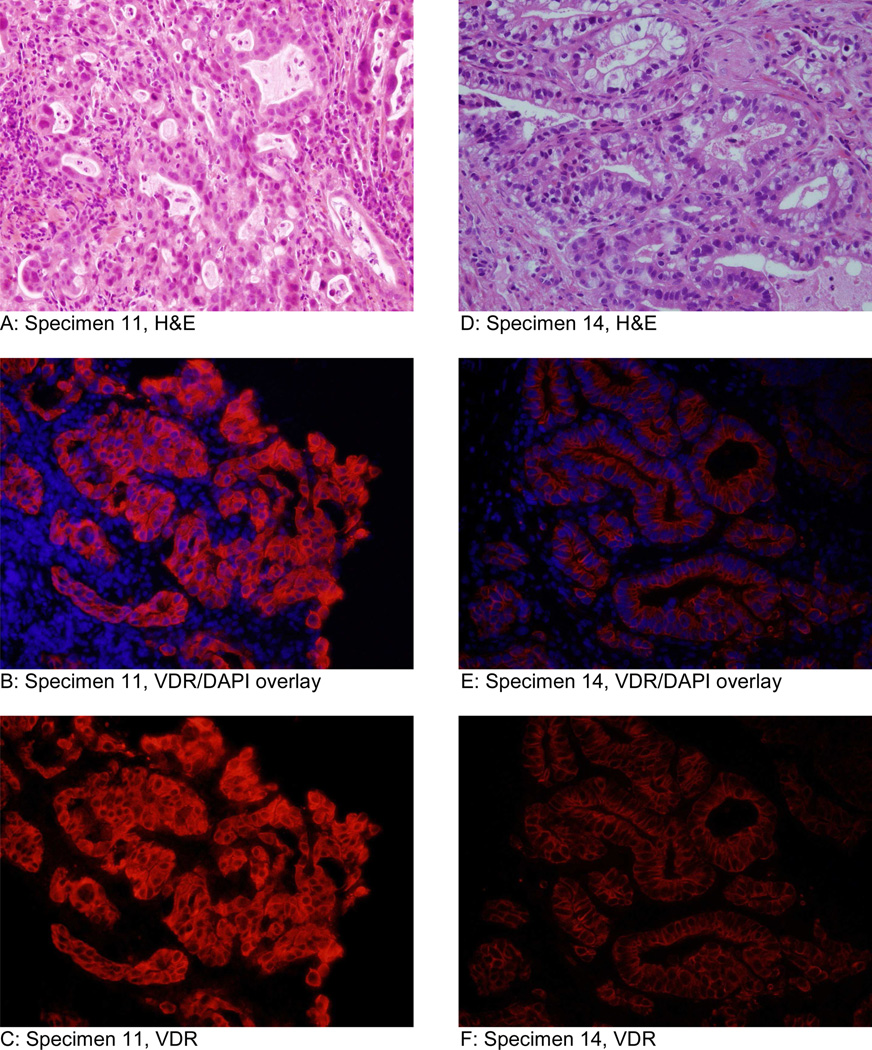

Moderately and well-differentiated tumors had greater average mean fluorescence intensity (111.7) than poorly differentiated tumors (98.7). The specimen that showed most intense immunofluorescencefluore for VDR was a moderately differentiated esophageal adenocarcinoma in the non-responders group (Figure 1 A-C). The specimen that stained least intensely was a moderately differentiated esophageal adenocarnoma in the complete responders group (Figure 1 D-F). Representative specimens of high fluorescent intensity and low fluorescent intensity from the non-responders group are displayed in Figure 2. Representative specimens of high fluorescent intensity and low fluorescent intensity from the complete responders group are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Representative micrographs of the specimen that fluoresced most intensely (specimen 1) and least intensely (specimen 15) at 40× objective. Both specimens were moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. Specimen 1 (A-C) was a non-responder and specimen 15 (D-F) from a complete responder. Images A and D are H&E. Images B and E are an overlay of VDR immunofluorescence and DAPI (nuclear counterstain). Images C and F are VDR immunofluorescence without DAPI.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence analysis in specimens from the non-responders group and are moderately differentiated esophageal adenocarcinomas. Specimen 2 (A-C) displayed the second strongest intensity in the non-responders group. Specimen 9 (D-F) displayed the lowest intensity in the non-responders group. Images A and D are H&E. Images B and E are an overlay of VDR immunofluorescence and DAPI (nuclear counterstain). Images C and F are VDR immunofluorescence without DAPI.

Figure 3.

Imunofluorescence analysis of tissue specimens from the complete responders group. Specimen 11 (A-C) is a moderately differentiated esophageal adenocarcinoma and displayed the second strongest intensity in complete responders group. Specimen 14 (D-F) is a poorly differentiated esophageal adenocarcinoma and displayed the second lowest intensity in the complete responders group. Images A and D are H&E. Images B and E are an overlay of VDR immunofluorescence and DAPI (nuclear counterstain). Images C and F are VDR immunofluorescence without DAPI.

DISCUSSION

The vitamin D receptor can be grouped with a cluster of nuclear receptors that have important functions in the enteric tract (20). In mice, VDR displays extensive expression in the lower digestive tract, colon and small intestine (21), and it is expressed in normal human colon (22). Vitamin D receptor mRNA has also been detected in the human esophagus (23). In our study, we found that VDR immunostaining is restricted to the columnar mucosa and glandular tissue of the gastric cardia, and in columnar metaplasia of the distal esophagus. The normal squamous mucosa does not stain for VDR.

Vitamin D is considered to protect against malignancies by dietary intake in colorectal cancer, skin, prostate and breast cancer (17). 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), the biologically active form of vitamin D, is a steroid hormone that exerts most of its biological activities by binding to a specific high-affinity nuclear receptor, the VDR. Although the primary function of 1,25(OH)2D3 is to regulate calcium absorption and control bone mineralization, upon binding to its cognate VDR, 1,25(OH)2D3 induces cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis in normal and transformed cells as well as alters the MAP kinase and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways involved in carcinogenesis (17, 24, 25). The extent of VDR expression may correlate with the neoplastic process. High VDR expression in prostate tumors is associated with a reduced risk of lethal cancer, suggesting a role of the vitamin D pathway in prostate cancer progression (26), and immunohistochemistry of basal cell carcinoma indicates an increase in VDR staining intensity compared to normal cells (27). In human colon, loss of VDR activity is associated with malignancy (22).

We observed low levels of expression of VDR by immunofluorescence in high grade tumors. This could be due to the low grade of tumor differentiation and marked cellular pleomorphism observed in these tumors at histological examination, which is possibly associated with a loss of expression of VDR. A similar reduction in VDR mRNA and protein has been observed with progressive tumor dedifferentiation in colon adenocarcinoma (25), supporting the hypothesis that VDR is down-regulated in poorly differentiated tissue and that lower expression indicates a poor prognosis (28).

VDR protein expression was present in the cytoplasm but not in the nucleus. Our findings are similar to other studies conducted in prostate and colon tissue that have evaluated the presence of VDR protein using immunohistochemistry (25, 26, 29), but in contrast to observations in the epidermis, which show mainly nuclear staining (27, 30, 31). Absence of nuclear expression of VDR protein may be due to shift in localization of this protein from nucleus to cytoplasm as neoplastic transformation takes place. Hendrickson and colleagues (26) postulated that the VDR antigens may be processed quickly in the nucleus after functioning and cytoplasmic staining may be a surrogate of VDR actions that are ultimately mediated in the nucleus. A substantial proportion of cytoplasmic VDR is co-localized with endoplasmic reticulum, the golgi complex, and microtubules. Cytoplasmic VDR mediates non-genomic actions of VDR including regulation of calcium and chloride channel activity, protein kinase C activation, and phospholipase C activity occurring through cytoplasmic signaling pathways such as protein kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase (32, 33).

The major obstacle to improved outcome in operable esophageal cancer is the inability to predict response to chemoradiation therapy. The expression of excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (ERCC1), glutathione S-transferase P1, and thymidylate synthase have been associated with clinical outcome in patients with esophageal and gastric cancers (34). We hypothesized that VDR expression may be associated with response to neoadjuvant therapy, and therefore VDR expression could act as a biomarker to predict clinical outcome in these patients. The results presented here show that higher intensity of VDR staining in pretreatment biopsies is associated with a lack of response to chemoradiation therapy. The lack of statistical significance could be due to limited sample size. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to evaluate relationship of VDR expression in pretreatment biopsies with response to neoadjuvant therapy.

There were significant limitations to this investigation. The study was inadequately powered to show statistical significance of the effect sizes observed. This was in part due to the considerable variability of staining intensity observed within groups, as well as heterogeneity within each sample. This variability is consistent with the variability reported in immunohistochemical staining of prostate tumors (26), and is possibly a result of an inherent heterogeneity of cellular division, differentiation, and gene expression concomitant to the uncontrolled proliferation characteristic of neoplasia. Additionally, immunofluorescence is inherently limited. Although every effort is made to avoid it, the potential to interject bias is present when adjusting contrast and exposure times for photography of the prepared slides. Furthermore, we have not validated analysis with ImageJ software as a method to quantify staining intensity. Finally, the lack of comparison with adjacent normal tissue from the same patient prevents complete interpretation of the staining intensity.

In summary, we herein show that: (i) VDR expression is present in esophageal adenocarcinoma, (ii) the level of expression may decline with tumor de-differentiation, (iii) VDR protein appears to translocate to the cytoplasm as neoplastic transformation occurs, and (iv) VDR expression may serve as a prognostic marker for responsiveness to neoadjuvant therapy. Considering the data obtained, it is plausible that the extent of VDR expression is related to tumor progression and response to therapy, but it is equally as plausible that these data are merely random. These findings should be used to generate new hypotheses and spur the planning of investigations that will yield more definitive findings.

Highlights.

Vitamin D receptor is expressed in the cells of esophageal adenocarcinoma

VDR expression is more intense in tumors with a non-response to neoadjuvant therapy than in tumors with a complete response

VDR expression may decline with tumor de-differentiation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, Wijnhoven BP, Tijssen JG, Fockens P, et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1662–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, McCarter MD, Chow WB, Gordon HS, Stewart AK, et al. Effect of histologic subtype on treatment and outcomes for esophageal cancer in the United States. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwer AL, Ballonoff A, McCammon R, Rusthoven K, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Schefter TE. Survival effect of neoadjuvant radiotherapy before esophagectomy for patients with esophageal cancer: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end-results study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73(2):449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenzie S, Mailey B, Artinyan A, Metchikian M, Shibata S, Kernstine K, et al. Improved outcomes in the management of esophageal cancer with the addition of surgical resection to chemoradiation therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(2):551–558. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courrech Staal EF, Aleman BM, Boot H, van Velthuysen ML, van Tinteren H, van Sandick JW. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97(10):1482–1496. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crehange G, Bonnetain F, Peignaux K, Truc G, Blanchard N, Rat P, et al. Preoperative radiochemotherapy for resectable localised oesophageal cancer: a controversial strategy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;75(3):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruol A, Castoro C, Portale G, Cavallin F, Sileni VC, Cagol M, et al. Trends in management and prognosis for esophageal cancer surgery: twenty-five years of experience at a single institution. Arch Surg. 2009;144(3):247–254. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.574. discussion 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbour AP, Jones M, Gonen M, Gotley DC, Thomas J, Thomson DB, et al. Refining esophageal cancer staging after neoadjuvant therapy: importance of treatment response. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(10):2894–2902. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gertler R, Stein HJ, Langer R, Nettelmann M, Schuster T, Hoefler H, et al. Long-term outcome of 2920 patients with cancers of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: evaluation of the New Union Internationale Contre le Cancer/American Joint Cancer Committee staging system. Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):689–698. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821111b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meredith KL, Weber JM, Turaga KK, Siegel EM, McLoughlin J, Hoffe S, et al. Pathologic response after neoadjuvant therapy is the major determinant of survival in patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(4):1159–1167. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahue JM, Nichols FC, Li Z, Schomas DA, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, et al. Complete pathologic response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer is associated with enhanced survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(2):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.001. discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzger R, Warnecke-Eberz U, Alakus H, Kutting F, Brabender J, Vallbohmer D, et al. Neoadjuvant Radiochemotherapy in Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus: ERCC1 Gene Polymorphisms for Prediction of Response and Prognosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1700-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bollschweiler E, Metzger R, Drebber U, Baldus S, Vallbohmer D, Kocher M, et al. Histological type of esophageal cancer might affect response to neo-adjuvant radiochemotherapy and subsequent prognosis. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(2):231–238. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider PM, Baldus SE, Metzger R, Kocher M, Bongartz R, Bollschweiler E, et al. Histomorphologic tumor regression and lymph node metastases determine prognosis following neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for esophageal cancer: implications for response classification. Ann Surg. 2005;242(5):684–692. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000186170.38348.7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(9):684–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eelen G, Gysemans C, Verlinden L, Vanoirbeek E, De Clercq P, Van Haver D, et al. Mechanism and potential of the growth-inhibitory actions of vitamin D and ana-logs. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(17):1893–1910. doi: 10.2174/092986707781058823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh J. Cellular and molecular effects of vitamin D on carcinogenesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung I, Han G, Seshadri M, Gillard BM, Yu WD, Foster BA, et al. Role of vitamin D receptor in the antiproliferative effects of calcitriol in tumor-derived endothelial cells and tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):967–975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoudi T, Arkani M, Karimi K, Safaei A, Rostami F, Arbabi E, et al. The-4817 G>A (rs2238136) variant of the vitamin D receptor gene: a probable risk factor for colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt DR, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors of the enteric tract: guarding the frontier. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(10 Suppl 2):S88–S97. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangelsdorf D. VDR : Anatomical Q-PCR Expression Data. Nuclear Receptor Singaling Atlas. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meggouh F, Lointier P, Pezet D, Saez S. Evidence of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-receptors in human digestive mucosa and carcinoma tissue biopsies taken at different levels of the digestive tract, in 152 patients. J Steroid Biochem. 1990;36(1–2):143–147. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90124-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Gottardi A, Dumonceau JM, Bruttin F, Vonlaufen A, Morard I, Spahr L, et al. Expression of the bile acid receptor FXR in Barrett's esophagus and enhancement of apoptosis by guggulsterone in vitro. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:48. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muti P, Benassi B, Falvo E, Santoro R, Galanti S, Citro G, et al. Omics underpins novel clues on VDR chemoprevention target in breast cancer. OMICS. 2011;15(6):337–346. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matusiak D, Murillo G, Carroll RE, Mehta RG, Benya RV. Expression of vitamin D receptor and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1{alpha}-hydroxylase in normal and malignant human colon. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(10):2370–2376. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendrickson WK, Flavin R, Kasperzyk JL, Fiorentino M, Fang F, Lis R, et al. Vitamin D receptor protein expression in tumor tissue and prostate cancer progression. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2378–2385. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichrath J, Kamradt J, Zhu XH, Kong XF, Tilgen W, Holick MF. Analysis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) receptors (VDR) in basal cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(2):583–589. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65153-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mimori K, Tanaka Y, Yoshinaga K, Masuda T, Yamashita K, Okamoto M, et al. Clinical significance of the overexpression of the candidate oncogene CYP24 in esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(2):236–241. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blomberg Jensen M, Andersen CB, Nielsen JE, Bagi P, Jorgensen A, Juul A, et al. Expression of the vitamin D receptor, 25-hydroxylases, 1alpha-hydroxylase and 24-hydroxylase in the human kidney and renal clear cell cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(1–2):376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milde P, Hauser U, Simon T, Mall G, Ernst V, Haussler MR, et al. Expression of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in normal and psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97(2):230–239. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12480255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brozyna AA, Jozwicki W, Janjetovic Z, Slominski AT. Expression of vitamin D receptor decreases during progression of pigmented skin lesions. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(5):618–631. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beno DW, Brady LM, Bissonnette M, Davis BH. Protein kinase C and mitogen-activated protein kinase are required for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-stimulated Egr induction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(8):3642–3647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kure S, Nosho K, Baba Y, Irahara N, Shima K, Ng K, et al. Vitamin D receptor expression is associated with PIK3CA and KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(10):2765–2772. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon HC, Roh MS, Oh SY, Kim SH, Kim MC, Kim JS, et al. Prognostic value of expression of ERCC1, thymidylate synthase, and glutathione S-transferase P1 for 5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):504–509. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]