Abstract

Background

Human cardiac progenitor cells have demonstrated great potential for myocardial repair in small and large animals, but robust methods for longitudinal assessment of their engraftment in humans is not yet readily available. In this study, we sought to optimize and evaluate the use of positron emission tomography (PET) reporter gene imaging for monitoring human cardiac progenitor cell (hCPC) transplantation in a mouse model of myocardial infarction.

Methods & Results

hCPCs were isolated and expanded from human myocardial samples and stably transduced with variations of the thymidine kinase (TK) PET reporter gene. TK-expressing hCPCs were characterized in vitro and transplanted into murine myocardial infarction models (n=60). Cardiac echocardiographic, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and pressure-volume (PV) loop analyses revealed improvement in left ventricular contractile function two weeks after transplant (hCPC vs. PBS, P<0.03). Noninvasive PET imaging was used to track hCPC fate over a four week time period, demonstrating a substantial decline in surviving cells. Importantly, early cell engraftment as assessed by PET was found to predict subsequent functional improvement, implying a “dose-effect” relationship. We isolated the transplanted cells from recipient myocardium by laser capture microdissection for in vivo transcriptome analysis. Our results provide direct evidence that hCPCs augment cardiac function after their transplantation into ischemic myocardium through paracrine secretion of growth factors.

Conclusions

PET reporter gene imaging can provide important diagnostic and prognostic information regarding the ultimate success of human cardiac progenitor cell treatment for myocardial infarction.

Keywords: cell therapy, stem cells, imaging, positron emission tomography

INTRODUCTION

Following myocardial infarction, the limited proliferative ability of the surviving cardiac cells renders the damaged heart susceptible to morbid sequelae such as unfavorable remodeling and heart failure. Although therapeutic options have advanced in the last several decades, the morbidity and mortality associated with ischemic cardiomyopathy remains unacceptably high1. In recent years, stem and progenitor cells have emerged as exciting new tools to alleviate left ventricular dysfunction alongside existing pharmacologic and device treatment options. In particular, human cardiac progenitor cells (hCPCs) demonstrate enormous potential for future clinical translation of cardiac cell therapy2. hCPCs are a clonogenic, self-renewing population that are pre-programmed for differentiation into cells of all three cardiac lineages in vitro: myocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. In addition, hCPCs can be derived autologously from a small sample of myocardial tissue3, thereby avoiding concerns of immunological rejection. Numerous small and large animal studies have concluded that transplantation of CPCs into ischemic myocardium yields significant improvement in cardiac function following myocardial infarction3–7.

Results from early clinical trials of bone marrow-derived cell therapy for cardiovascular disease have yielded promising but variable results8, 9, while results of early clinical trials of hCPC therapy are still forthcoming10. Many questions remain regarding the optimal cell type, dose, and timing of any such cell therapy. Robust evaluation of these parameters has been greatly aided by the development of noninvasive imaging methods for longitudinal assessment of stem cell engraftment and proliferation. Direct labeling of cells using radiotracers11–13 or magnetic particles14, 15 allows short-term visualization of transplant location, but death of the cells may lead to erroneous signal from neighboring phagocytes or interstitium. The temporal limitations of these physical methods for labeling cells have been overcome by techniques for stable labeling of cells with various reporter genes, thereby enabling quantitative assessment of cell survival and proliferation. In this regard, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) in conjunction with luciferase reporter genes has been used previously to monitor the survival of stem cell transplants6. However, BLI will not be applicable in humans because its low energy photons (2–3 eV) are easily attenuated within the deeper tissues of larger animals.

Positron emission tomography (PET), on the other hand, is a clinically applicable noninvasive imaging modality that readily allows for the monitoring of cell homing in humans16. Various generations of PET thymidine kinase (TK) reporter genes have been developed in recent years to optimize our collective ability to monitor various cellular processes, including transcriptional regulation, protein-protein interactions, and cell trafficking17–20. Here we sought to compare the various generations of PET TK reporter genes for their potential use in monitoring clinical hCPC therapy. Furthermore, we sought to determine whether early PET imaging would provide prognostic information about the ultimate success of cell therapy trials. Our results indicate that an imaging component of future clinical cell therapy trials will yield significant insight into the determinants of successful treatment.

METHODS

Isolation, culture, and characterization of human cardiac progenitor cells (hCPCs)

The study was conducted with institutional approval from the Stanford Investigational Research Board (IRB). The hCPCs were isolated based on a previously described protocol using magnetic separation in conjunction with a Sca-1 antibody21–23. In brief, human fetal hearts were collected after elective abortion by a commercial vendor (StemExpress, Placervill, CA). Fetal hearts underwent Langendorff perfusion with Tyrode's solution containing collagenase and protease. Cardiomyocyte progenitor cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting (MACS, Miltenyl Biotec, Sunnyvale, CA) using Sca-1-coupled magnetic beads, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sca-1+ cells were eluted from the column by washing with PBS supplemented with 2% FBS and cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes in M199 (Gibco)/EGM-2 (3:1) supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco), 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), 5 ng/ml epithelial growth factor (EGF), 5 ng/ml insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), and 5 ng/ml hepatocyte growth factor (HGF).

Lentiviral vector construction and transduction of hCPCs with Fluc-GFP double fusion reporter genes

See Supplemental Methods for details.

Effect of TK variants on hCPC viability, proliferation, and differentiation potential

See Supplemental Methods for details.

Microarray hybridization and data analysis of various TK-hCPC lines

See Supplemental Methods for details.

In vitro [18F]-FHBG accumulation assay

See Supplemental Methods for details.

Surgical model of myocardial infarction and hCPC delivery

In adult female SCID Beige mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), myocardial infarction was induced by ligation of the left coronary artery under 1.5–2% inhaled isoflurane anesthesia, and confirmed by myocardial blanching and EKG changes. Animals were initially randomized into 5 experimental groups receiving hCPCs (n=60) or 1 control group receiving PBS (n=15). Four of the 5 experimental groups received hCPCs that stably expressed the different variants of the PET TK reporter gene shown in Figure 1A. The PET TK reporter gene variants were the original wild-type herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV) thymidine kinase (wt-tk), semi-random variant 39 HSV-thymidine kinase (sr39-tk), A168H mutant HSV-tk (A168H), and truncated mitochondrial thymidine kinase type 2 (Δhtk2) (A168H and Δhtk2 were courtesy of Dr. Juri Gelovani at MD Anderson)17–20. Animals were randomized to the groups as follows: wt-tk-hCPCs (n=5), sr39-tk-hCPCs (n=20), A168H-hCPCs (n=20), and Δhtk2-hCPCs (n=5). One experimental group received untransduced hCPCs (n=10). All 5 experimental groups were injected with 1×106 cells using a 31-gauge Hamilton syringe immediately after MI. In all groups, the volume of injection was 20 μl at 3 sites near the peri-infarct border zone. All surgical procedures and injections were performed by a single experienced and blinded investigator (Y.G.).

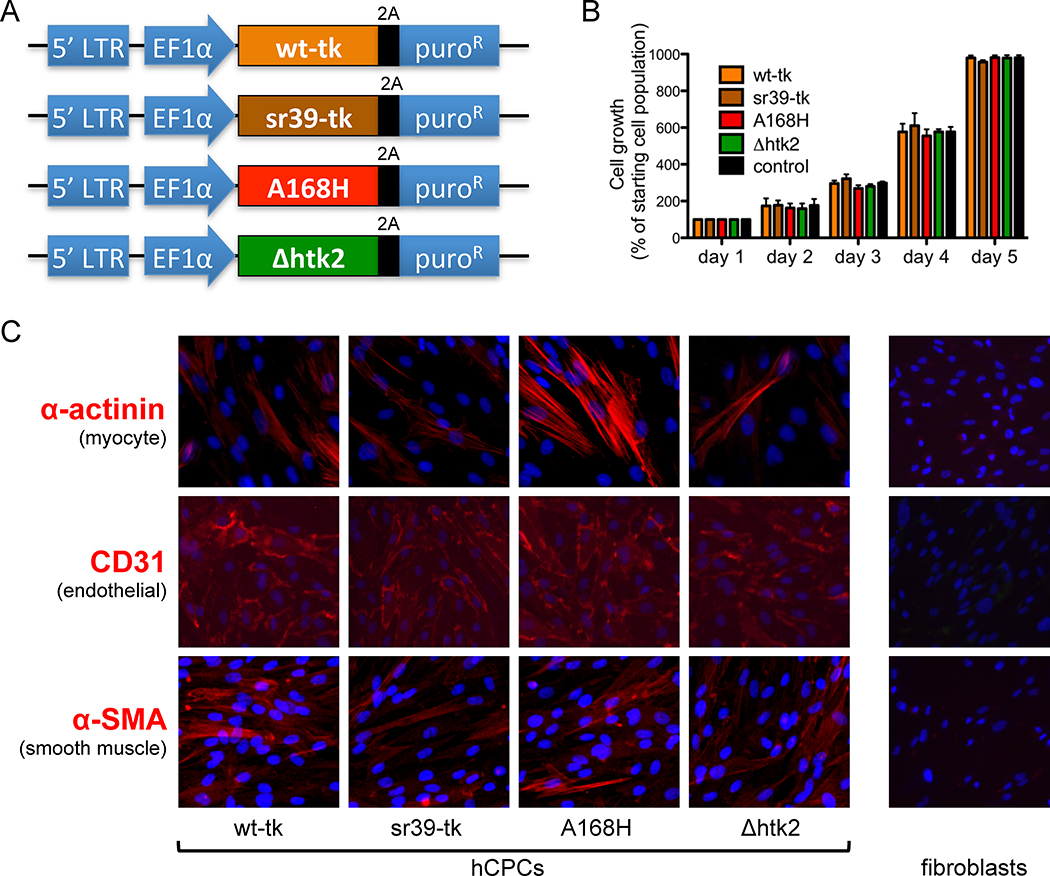

Figure 1.

Human cardiac progenitor cell (hCPC) phenotype is unaffected by expression of thymidine kinase PET reporter genes. (A) Schematic of lentiviral constructs expressing four variant thymidine kinase PET reporter genes. (B) No significant difference in proliferation rate was observed among hCPCs transduced with various thymidine kinase reporter genes versus control untransduced hCPCs. (C) Immunohistochemical staining of differentiating hCPCs demonstrates cells of all three cardiac lineages: myocyte (marked by α-actinin), endothelial (marked by CD31), and smooth muscle (marked by α-SMA) after transduction with thymidine kinase reporter genes. Fibroblasts (far right) serve as a negative control and do not stain for any cardiac markers.

[18F]-FHBG positron emission tomography (PET) imaging

Small animal microPET imaging (Vista system, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, United Kingdom) was performed in a subset of the animals (n =40 hCPCs and n = 15 PBS) on days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28 postoperatively. Mice were fasted for 3 hr before radioisotope injection. Animals were then injected with approximately 7,400 kBq (200 mCi) of [18F]-FHBG radiotracer via the tail vein. At 60 min after injection, animals were anesthetized with inhaled 2% isoflurane. Images were acquired, reconstructed by filtered back projection, and analyzed using image software AMIDE (SourceForge, Inc., Mountain View, California) by a blinded investigator (M.H.). Three-dimensional regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn encompassing the heart. For each ROI, counts/ml/min were then converted to counts/g/min and divided by the injected dose to obtain the image ROI derived [18F]-FHBG percentage injected dose per gram of heart (%ID/g).

Bioluminescence imaging of hCPC engraftment for confirmation of PET data

See Supplemental Methods for details

Analysis of left ventricular function with echocardiogram and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

See Supplemental Methods for details.

Analysis of left ventricular function with pressure-volume (PV) loops

See Supplemental Methods for details.

Analysis of in vivo gene expression using laser capture microdissection (LCM)

Mouse hearts were removed after perfusion with 20 ml phosphate buffer saline (PBS), embedded in OCT, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. For LCM, seven thick tissue sections of the left ventricle were prepared on polyethylene napthalate (PEN) membrane coated slides (MicroDissect GmbH, Leica, Germany). The slides were then thawed briefly and air-dried for 5 min before dissection. Green fluorescence observed under laser microscopy was used as a landmark for microdissection. GFP+ cells, indicating transplanted hCPCs, were dissected using a Leica AS LMD6000 system (Leica, Germany). GFP− recipient myocardium was also isolated for normalization. The dissected tissues were placed into the caps of microcentrifuge tubes with 5 μl of lysis enhanced buffer, and collected by centrifugation at 8000 × g for 5 minutes. Total RNA extraction and reverse transcription of these samples were performed using a commercial One Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Histological examination

See Supplemental Methods for details.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were calculated using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), Stata Release 9.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and R 2.14.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Unless specified, descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance with post hoc testing was used as indicated in figure legends. Differences between the high and low cell engraftment groups in percent fractional shortening (%FS) as evaluated by echocardiography, ejection fraction (EF) as evaluated by cardiac MRI, and cell engraftment as evaluated using PET were tested with a mixed effects regression on number of days post-transplantation, cellular engraftment (high vs low or hCPC vs PBS), and their interaction, with mouse as a random effect. An autoregressive model of order 1 (AR(1)) correlation structure was used to model the dependence of within-mouse measurements. Significance of time and treatment effect was assessed via a likelihood ratio test, comparing to the null model with no time or treatment effect. Correlations among PET signal, EF, and %FS were assessed by Spearman rank correlation. Differences were considered significant at a P-values of <0.05 unless they were subject to a Bonferroni-adjusted critical P-value as indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Isolation, expansion, and features of human cardiac progenitor cells isolated from human myocardial biopsy specimens

We first isolated Sca-1+ hCPCs from human fetal hearts and clonally expanded them using a previously described protocol24 (see Supplemental Methods). The identity of the isolated cells was validated by cell surface marker (Supplemental Figure 1) and gene expression profiling (Supplemental Figure 2) prior to stable transduction with a double-fusion firefly luciferase (Fluc) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene cassette. GFP+ cells were FACS isolated and expanded to generate stableFluc+/GFP+hCPC lines that can be quantitatively tracked in vivo using bioluminescence imaging (BLI) (Supplemental Figure 3).

Expression of thymidine kinase PET reporter genes does not affect the phenotype of human cardiac progenitor cells

Fluc+/GFP+hCPCs were stably-transduced with four variants of the PET TK reporter gene that had been chosen for further evaluation (Figure 1A). They were the original wild-type herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV) thymidine kinase (wt-tk), semi-random variant 39 HSV-thymidine kinase (sr39-tk), A168H mutant HSV-tk (A168H), and truncated mitochondrial thymidine kinase type 2 (Δhtk2)17–20. sr39-tk was developed in 2000 by random sequence mutagenesis of the nucleoside binding region of wt-tk and selected for an enhanced ability to convert the prodrug acyclovir and/or ganciclovir into cytotoxic agents25. A168H was later developed in 2006 by engineering of a single conserved residue of the wt-tk gene based on its crystal structure26. Δhtk2 was derived from human mitochondrial thymidine kinase type 2 by truncation of the N-terminal nuclear localization signal in 200720. Although all variants of thymidine kinase have been developed with an aim of enhanced sensitivity and specificity, there have not yet been direct comparisons of their use as reporter genes for cardiac stem cell therapy

To address this question, we stably transducedFluc+/GFP+hCPCs with the various thymidine kinase reporter genes, and observed no discernible adverse effects on cell proliferation (Figure 1B), cell viability (Supplemental Figure 4), gene expression profile (Supplemental Figure 5), or karyotype (Supplemental Figure 6). Most importantly, stably transduced hCPCs maintained their ability to differentiate into all three cardiac lineages, as evidenced by expression of α-actinin, CD31, or α-SMA (Figure 1C).

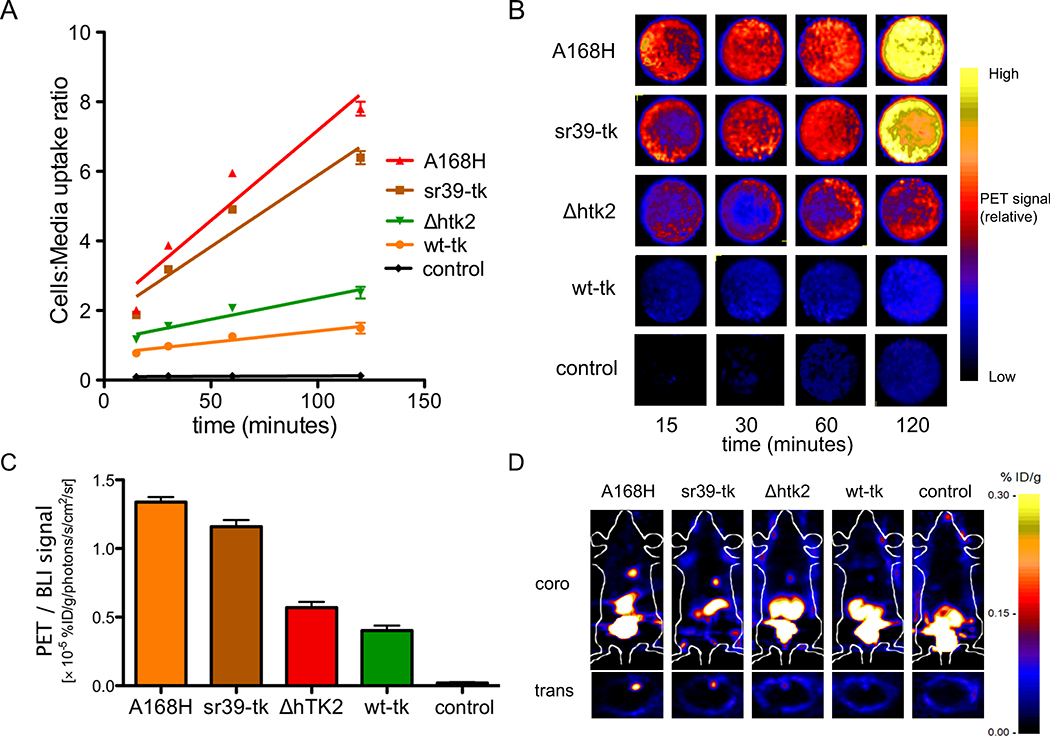

Comparison of [18F]-FHBG radiotracer uptake rates by different TK variants

We wished to assess the utility of PET reporter gene imaging in the setting of clinical stem cell transplantation trials, and thus opted to use the [18F]-FHBG radiotracer in conjunction with TK reporter gene variants. [18F]-FHBG is a positron-emitting nucleoside analog used in conjunction with TK for imaging of gene expression. The safety, pharmacokinetics, and dosimetry of18F FHBG have been studied in rats, rabbits, and human volunteers, and the US Food and Drug Administration has approved its use as an investigational new drug (IND #61880) for clinical trials27. Radiotracer uptake into hCPCs was quantified in vitro over a 120-minute time course using a gamma counter (Figure 2A), and confirmed qualitatively using microPET imaging acquisition (Figure 2B). Robust uptake was highest in the hCPCs stably expressing the A168H and sr39-tk variants (cells to media uptake ratio of 7.80 ± 0.20 and 6.40 ± 0.19, respectively). Next, we confirmed the ability of various TK variants to uptake radiotracer in an in vivo setting by transplanting TK-expressing hCPCs intramyocardially into SCID beige mice (Figure 2C–D). PET signal intensities were compared after normalization for any experimental variation in cell number by concurrently measuring BLI signals (because the parent hCPC line also stably expressed the GFP-Fluc double fusion reporter gene). hCPCs expressing A168H or sr39-tk displayed the highest PET signal intensities, confirming our in vitro observations (1.34 ± 0.06 and 1.16 ± 0.08 %ID/g, respectively). hCPC lines stably expressing the A168H TK variant were then expanded for all subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

Differential uptake of [18F]-FHBG by TK-expressing hCPCs in vitro and in vivo. (A) Four variants of thymidine kinase (TK) exhibit differential uptake of [18F]-FHBG in vitro. Uptake of [18F]-FHBG was highest in hCPCs stabling expressing the A168H and sr39-tk variants. (B) MicroPET qualitative assessment of [18F]-FHBG uptake in TK-expressing hCPCs confirms results from gamma counting in Figure 2A. (C) TK-expressing hCPCs display differential uptake of [18F]-FHBG in vivo. hCPCs stably expressing the A168H and sr39-tk variants exhibited the highest PET signals after normalization to bioluminescence imaging (BLI) to control for inadvertent variations in transplanted cell number. (D) Representative images of adult SCID beige mice 24hrs after intramyocadial transplantation of 1×106 TK-expressing hCPCs.

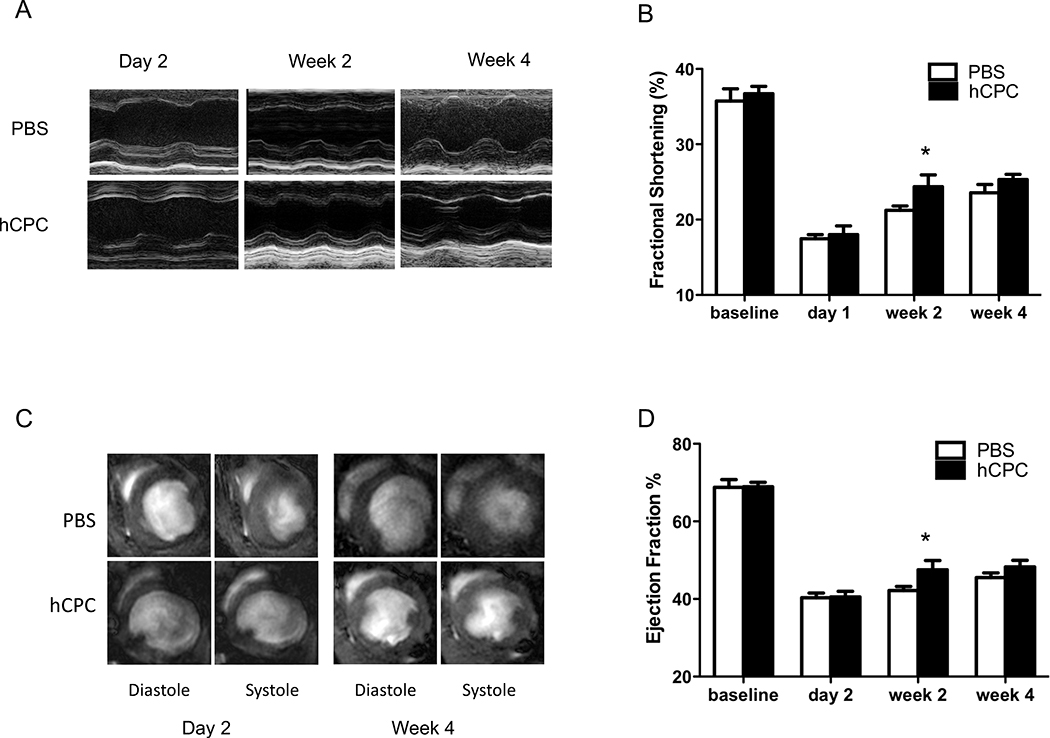

Transplantation of human cardiac progenitor cell improves left ventricular contractility

Adult SCID beige mice were subjected to LAD artery ligation followed by injection with either 1×106 hCPCs (n=37) or PBS (n=10). To determine the effect of hCPC transplant on myocardial left ventricular (LV) function, we carried out echocardiographic (Figure 3A) and MRI (Figure 3C) assessments over the four week study period. Compared to control animals injected with PBS, hCPC-treated animals demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in fractional shortening (Figure 3B) as well as ejection fraction (Figure 3D) at day 14 post-transplant, as assessed by echocardiography and MRI, respectively. A statistically significant difference in ejection fraction was also detected between the hCPC-treated and untreated PBS controls at week 4 post-transplant. However, no statistically significant differences in fractional shortening were observed between the hCPC-treated and untreated PBS controls at week 4 post-transplant.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of cardiac contractility by echocardiography and cardiac MRI. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiogram of hearts receiving hCPCs vs. PBS at day 2, week 2, and week 4. Baseline measurements are shown to represent healthy heart function, but are not considered in the statistical analysis. (B) Comparison of fractional shortening as evaluated by echocardiography at baseline, day 2, week 2, and week 4 after LAD ligation. hCPC-treated hearts (n=37) demonstrated a transient improvement in fractional shortening at week 2 post-transplant as compared to saline controls (n=10). (Linear mixed effects model using treatment with hCPC or PBS, time (day 1, week 2, week 4) and treatment X time interaction as fixed effects, mouse as a random effect, with repeated observations over time. Significance of treatment effect at a given time point was assessed via tests of contrasts of the parameter estimates. Effect deemed significant at the Bonferroni-corrected level 0.05/3=0.016. P=0.0016 for treatment effect at week 2). (C) Representative MR images of hearts receiving hCPCs vs. PBS at day 2 and week 4. (D) Comparison of ejection fraction as assessed by cardiac MRI at baseline, day 2, week 2, and week 4. hCPC-treated hearts (n=37) demonstrated an improvement in ejection fraction at week 2 post-transplant as compared to saline controls (n=10) which persisted at week 4 (Linear mixed model as in Figure 3B. P=0.0016 at week 2; P=0.003 at week 4).

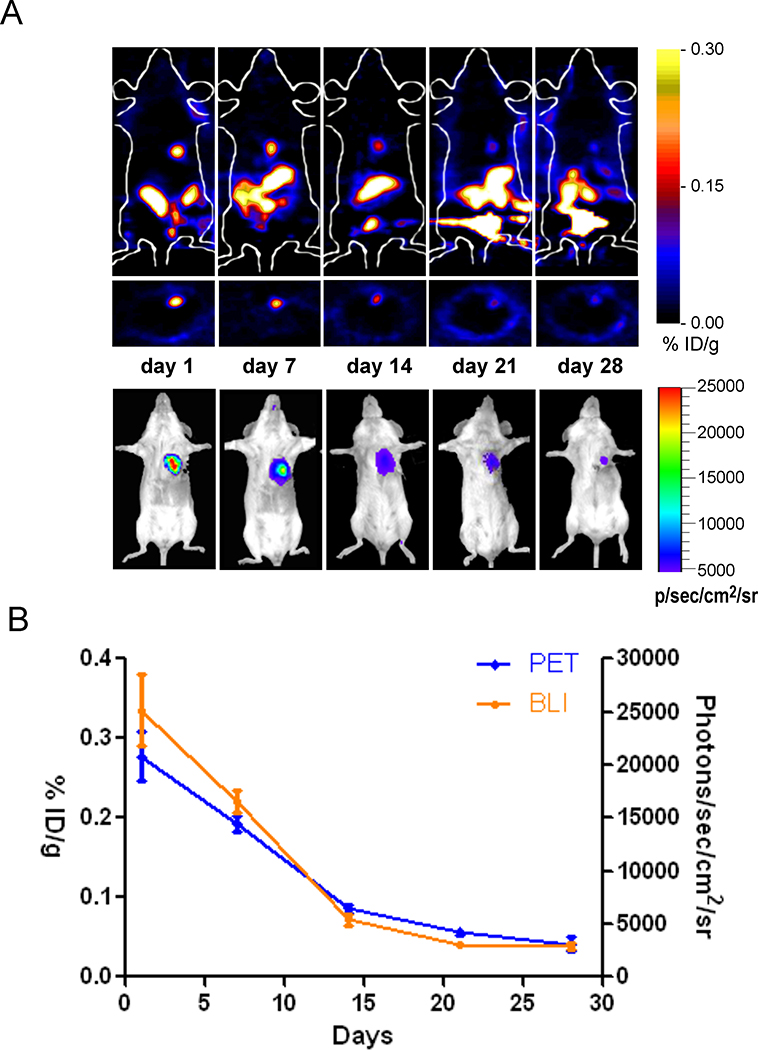

Temporal kinetics of human cardiac progenitor cell survival in ischemic myocardium

We next sought to quantitatively assess the dynamics of cellular engraftment using PET imaging. We carried out serial PET imaging of the hCPC-treated animals, and observed loss of PET signal intensity over time, reflecting death of the transplanted cells over the 28-day study period (Figure 4A-4B). These results were confirmed independently using BLI of Fluc expression within the same animals (Supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 4.

Temporal kinetics of hCPC survival in living animals. (A) Longitudinal PET imaging of a representative adult female SCID mouse injected with 1×106 hCPCs stably expressing the A168H variant of TK. (B) Progressive decrease in both PET and BLI signal intensity was observed over the 28 day time course (n=37).

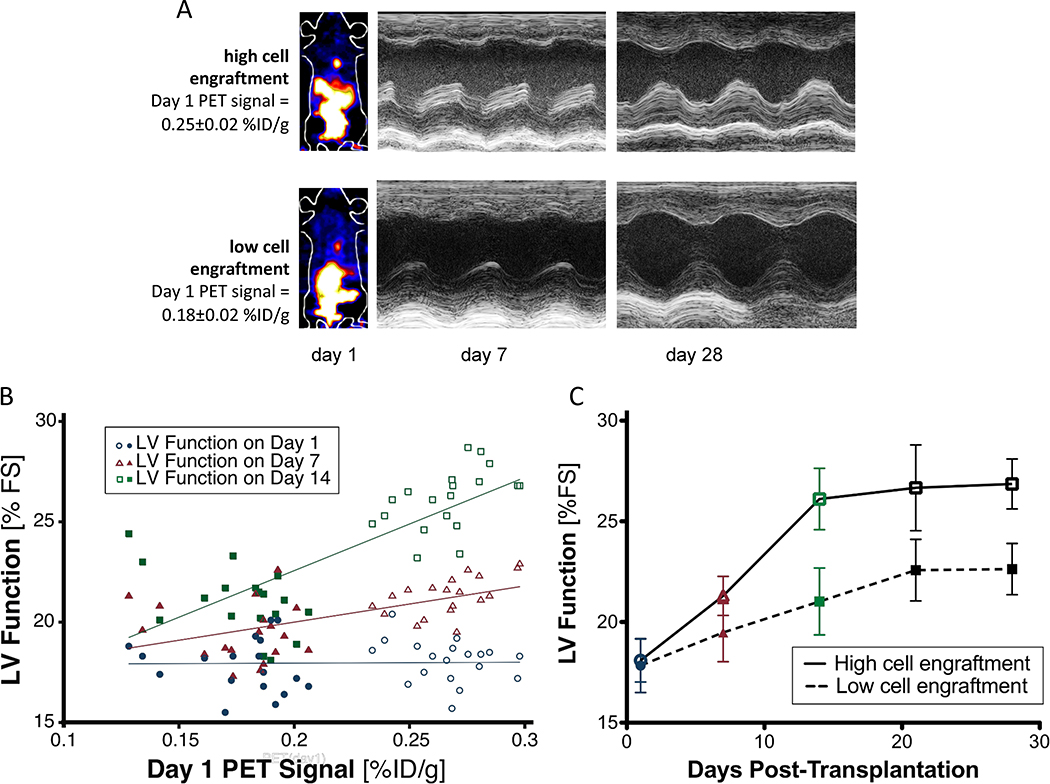

Early PET imaging predicts subsequent myocardial functional improvement

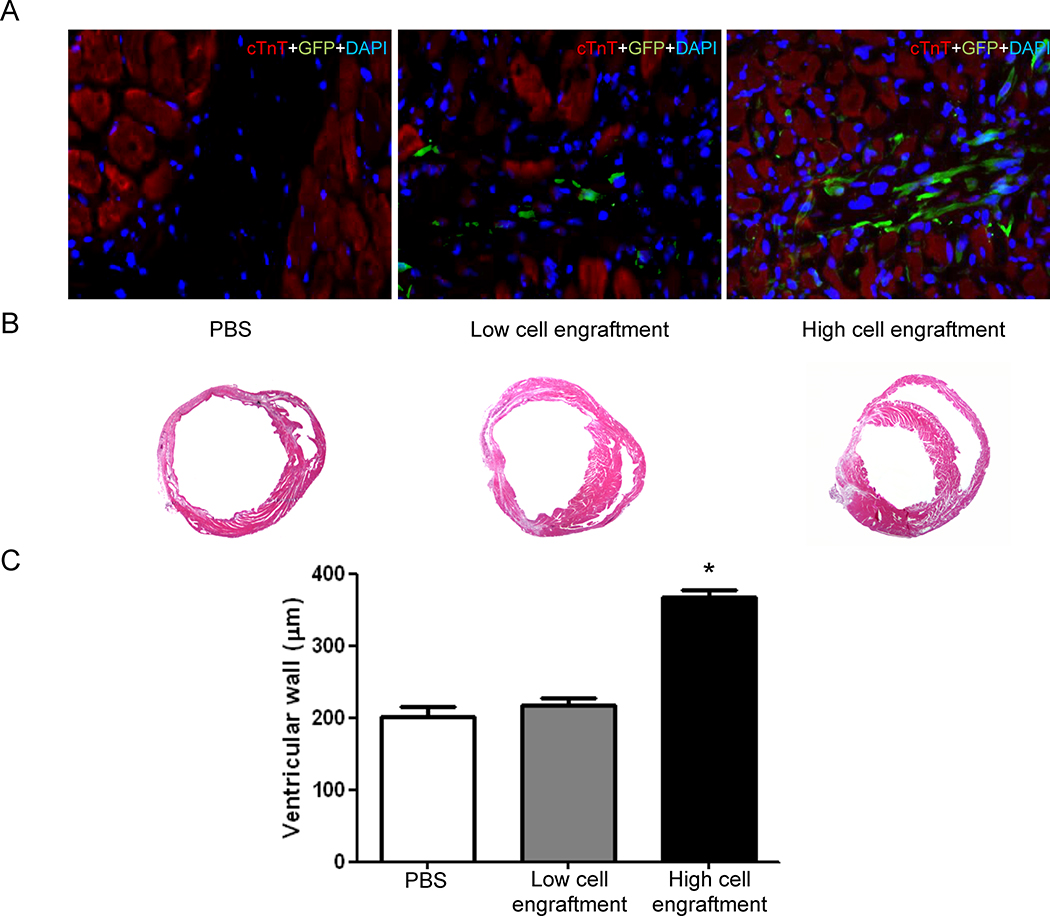

In light of the variable results of cell-based therapy in recent clinical trials8, 9, we decided to evaluate whether a high degree of early cellular engraftment was predictive of late therapeutic benefit. Using PET imaging data obtained on day 1 after cell transplant as a surrogate measure of cell engraftment, we stratified the hCPC transplant recipients in our cohort into high and low engraftment groups (Figure 5A). A basic finite mixture model of Gaussian distributions inferred two equal size groups (P<0.001) with a cut-off at 0.22% ID/g (mean ± SD of the two groups: 0.18 ± 0.02 % ID/g vs. 0.27 ± 0.02 % ID/g). Substantial variation in PET signal intensity was observed at day 1 post-transplant, with no correlation to initial LV function measured on day 1. Variable engraftment is likely attributed to imperfections in the intramyocardial delivery of hCPCs, and corresponds to the degree of variation expected in a clinical setting, where initial retention may range from 1% to 19% of delivered cells depending on the mode of delivery11. Initial PET signal intensity at day 1, as a surrogate measure of engraftment success, correlated well with LV function as assessed by echocardiography at week 1 (ρ=0.64), and correlated best with LV function at week 2 (ρ=0.76; Figure 5B). Cardiac MRI assessment of myocardial function also correlated well to initial PET signal intensity at day 1 (ρ=0.80; P<0.0001; n=34). Over the course of the four-week study period, the low cell engraftment group did not demonstrate any statistically significant improvements in LV function when compared to untreated animals (P = 0.68). However, there was a significant difference in the trend over time between the high and low cell engraftment groups (P<0.001, Figure 5C). The results of the stratification into high and low engraftment groups were confirmed independently by cardiac MRI assessment of LV ejection fraction (Supplemental Figure 8) and pressure-volume loop analysis of end-systolic volume and end-systolic pressure (Supplemental Figure 9). We then independently confirmed a positive correlation between cellular engraftment and ventricular wall thickness using gross histological and immunohistochemical staining (Figure 6). Therefore, the number of surviving hCPCs at early time points directly correlates with the degree of functional improvement at later time points in a “dose-effect” relationship. These results underscore the utility of robust methods for quantitative monitoring of cellular engraftment to better understand the complex determinants of successful cell therapy28.

Figure 5.

Early PET imaging predicts myocardial functional improvement. (A) Representative images of mice with high day 1 PET signal signifying high hCPC engraftment (top) and low day 1 PET signal signifying low hCPC engraftment (bottom). Representative M-mode echocardiogram demonstrates functional improvement at week 2 with high engraftment (top) but not with low engraftment (bottom). (B) Significant variability of PET signal intensity (horizontal axis) occurs in various recipient animals on day 1, with minimal correlation to left ventricular function (vertical axis) measured on day 1 (blue circles; ρ=0.02). Day 1 PET signal intensity correlates well with cardiac function at week 1 (red triangles; ρ=0.64), and correlates best with cardiac function at week 2 (green squares; ρ=0.76). Open symbols represent mice in the high cell engraftment group, while filled symbols represent mice in the low cell engraftment group. Rho ρ denotes Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (n=37). (C) Separation of the hCPC cohort into high and low engraftment categories demonstrates a significant difference in trend over time between the categories (Linear mixed model with high vs low engraftment, time, and group X time interaction as fixed effects, mouse as random effect. P<0.001; n=37 total, n=19 in the high cell engraftment group, n=18 in the low cell engraftment group).

Figure 6.

Ex vivo histological confirmation of in vivo PET imaging data. (A) hCPCs engrafted within the recipient myocardium at day 14 after injection. Higher levels of GFP+ hCPCs are identified within the hearts with higher day 1 PET signal. (B) Myocardial wall thickness in representative thin sections of gross hearts at day 14 after injection. (C) Significant enhancement of myocardial wall thickness in the hearts engrafting high levels of hCPCs (One way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; *P<0.0001 (n=12/group).

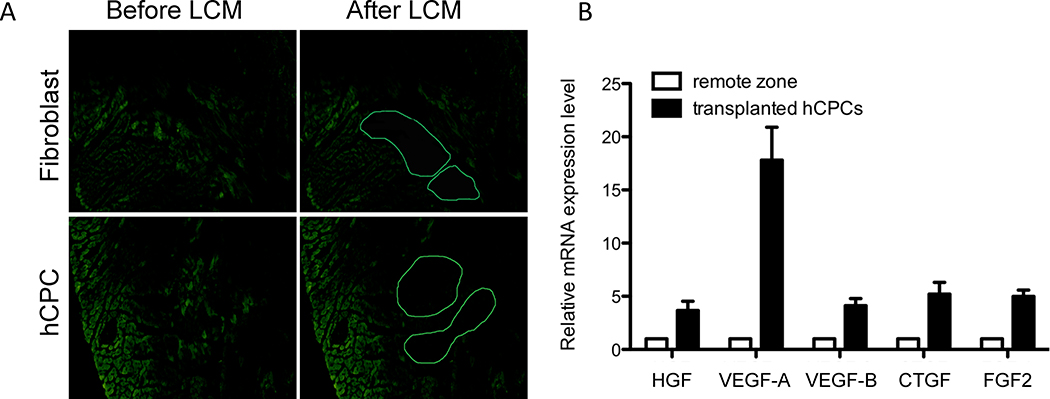

hCPC expression of paracrine growth factorsin vitro and in vivo

Although some studies have demonstrated a therapeutic benefit of stem cell therapy on myocardial contractility in large animals4, 5 and humans 8, 9, the mechanism(s) by which stem cells might exert their beneficial effects has remained somewhat controversial. Hypotheses include paracrine stimulation of recipient myocardium, direct cardiomyogenesis, and mechanical mitigation of wall strain. In support of the role that paracrine secretion may play in augmenting cardiac function, we found that hCPCs grown in hypoxic culture conditions upregulated expression of multiple anti-apoptotic growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Supplemental Figure 10). However, we also sought to address this question by examining the effect of transplantation on CPC phenotype using immunohistochemistry and laser capture microdissection (LCM). LCM allows isolation of hCPCs after their transplantation into recipient myocardium, thereby allowing evaluation of the in vivo transcriptional program of hCPCs (Figure 7A). We found that hCPCs isolated from recipient myocardium by LCM had significantly upregulated their expression of growth factor transcripts in vivo, particularly VEGF-A, VEGF-B, FGF2, and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (Figure 7B). In contrast, immunohistochemical staining of transplanted GFP+ CPCs was negative for markers of cardiac or endothelial differentiation such as α-actinin and CD31 (Supplemental Figure 11). We examined the cardiac differentiation potential of CPCs more thoroughly by assessing transplanted CPCs over time using LCM and an array of cardiac markers. Transcript markers of early cardiac differentiation such as GATA4 and TBX5, as well as definitive cardiomyocyte markers such as MYL2, TNNI2, TNNT2, MYH6, and ACTN2 were all negative in >95% of the transplanted GFP+ CPCs (Supplemental Figure 12). Therefore, our findings support the hypothesis that hCPC transplantation improves cardiac functional recovery due to paracrine secretion of growth factors rather than direct cardiomyogenesis. While studies thus far have inferred the behavior of stem/progenitor cells based on their in vitro response to hypoxia, we have demonstrated here that hCPCs upregulate transcription of anti-apoptotic growth factors in vivo after their transplantation into ischemic myocardium. Our results are in agreement with those of other groups suggesting that paracrine secretion plays the dominant role in ameliorating left ventricular dysfunction after transplantation of cardiac stem cells29, 30.

Figure 7.

In vivo growth factor gene expression response of hCPCs to myocardial ischemia. (A) Laser capture microdissection (LCM) was used to identify and isolate GFP+ hCPCs at day 14 after injection for RNA extraction. (B) qPCR of transplanted hCPCs isolated using LCM reveals upregulation of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and CTGF growth factor genes in vivo as compared to control samples isolated from a remote zone of the same heart. (n=5/group)

DISCUSSION

Several parameters for hCPC identification are currently found in the literature, including isolation of c-kit+ cells31, cardiosphere-derived cells32, Sca-1+ cells24, and Isl1+ cells33. These various hCPC formulations have all demonstrated a degree of efficacy in animal studies, although evaluation of the degree of overlap between these various populations and their comparative efficacy is needed in the future. Here we tested four different variations of the TK PET reporter gene in conjunction with the [18F]-FHBG PET reporter probe to monitor Sca-1+ hCPC therapy. The transcriptome and differentiation capacity of hCPCs was not affected by stable expression of the TK reporter gene. hCPC survival in murine ischemic myocardium was subsequently monitored using BLI and PET, and was noted to decline substantially over the four week study period. Nonetheless, hCPC therapy transiently ameliorated the negative consequences of myocardial infarction, as demonstrated by echocardiographic, cardiac MRI, and PV loop evaluation of LV function. Importantly, early PET imaging assessment of the success of hCPC engraftment at day 1 was found to correlate positively with subsequent LV functional improvement at day 14. The mechanism by which hCPCs exert their functional benefits include upregulation of paracrine growth factor expression in treated hearts.

Clinical trials of stem cell therapies for myocardial repair have become a reality in recent years. Preliminary results from the SCIPIO trial have demonstrated that autologous c-kit+ Lin− cardiac stem cells can enhance myocardial function in patients who have suffered myocardial function up to one year after treatment10. A second phase I study has also reported encouraging preliminary data (CADUCEUS; CArdiosphere-Derived aUtologous stem CElls to Reverse ventricUlar dySfunction)34. Two recent meta-analyses of studies evaluating bone marrow-derived cell therapy for myocardial repair have also reported a modest yet significant 3–4% augmentation in LV ejection fraction8, 9. However, the mechanism(s) by which stem cells exert their beneficial effects has remained controversial. In agreement with others29, the mechanism of functional benefit in our study appears to involve upregulated expression and secretion of various growth factors.

Irrespective of the relative contribution of the multiple complementary mechanisms of stem cells' effects, the ultimate success of any given cell therapy will likely depend upon the successful delivery and engraftment of a sufficient number of transplanted cells. Cell-based myocardial repair strategies have thus far remained hindered by poor engraftment (<10%) of all cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells35, bone marrow mononuclear cells36, human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes37, and cardiosphere-derived cells5. Robust methods for longitudinal monitoring of cell engraftment will therefore play a necessary and vital role in better understanding the complex determinants of successful cell therapy28.

In the present study, we optimized PET reporter gene imaging as a surrogate marker of the success of hCPC engraftment, and demonstrated the role of PET imaging in providing important prognostic information regarding which recipients were likely to functionally benefit from hCPC transplant in subsequent follow-up. Due to the considerable biological complexity of any potential therapeutic cell product and its interaction with the host, as well as the relatively simple current techniques for delivery, clinical application of cell therapy will likely demonstrate wide variability in the engraftment of administered cells. Early assessment of engraftment success using the clinically-applicable imaging modalities demonstrated here could significantly and positively impact the course of care, potentially identifying which patients are candidates for additional rounds of cell therapy administration due to undertreatment. The positive correlation of day 1 PET signal with week 2 left ventricular contractility as described herein also implies a theoretical “dose-response” relationship for hCPC therapy, and bodes well for its future success as a treatment option alongside pharmacological therapies. Even more favorable results may be achieved in the future using strategies aimed at prolonging cell survival, such as pro-survival cocktails38 or genetic modification39, whereby the incremental benefits can also be monitored by imaging of cell fate. As the field of cardiac cell therapy continues to mature, an improved understanding of the determinants of success has become crucial, and noninvasive imaging approaches as outlined here are likely to play a significant role in this effort40.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Human cardiac progenitor cell (hCPC) transplantation is an exciting new therapy to ameliorate cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction. However, much remains to be understood regarding the parameters for successful cell therapy, including the optimal cell dose, engraftment rate, long-term survival, and delivery route. Molecular imaging techniques can be used to monitor the retention, engraftment, and delivery of stem cells after their delivery in vivo. In this study, we stably modified hCPCs to express variants of the thymidine kinase (TK) reporter gene, thereby enabling use of positron emission tomography (PET) to monitor cellular engraftment and survival after intramyocardial delivery. We found that hCPC transplantation resulted in a modest improvement in myocardial contractility, and that this improvement in contractility correlated with the number of engrafted cells at early time points. Importantly, we showed that cellular engraftment at early time points can provide valuable prognostic information regarding the ultimate success of hCPC transplant at later time points. In light of the variable response to cell transplantation seen in recent clinical cell therapy trials, molecular imaging techniques may prove pivotal to ensuring adequate cellular delivery and optimizing patient outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to acknowledge funding support from Burroughs Wellcome Foundation, R01 EB009689, RC1HL099117, R01HL093172 (JCW), RSNA R&E Foundation (KHN), and ACC/GE Cardiovascular Imaging Award (PKN).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollini S, Smart N, Riley PR. Resident cardiac progenitor cells: At the heart of regeneration. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2011;50:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis DR, Kizana E, Terrovitis J, Barth AS, Zhang Y, Smith RR, Miake J, Marban E. Isolation and expansion of functionally-competent cardiac progenitor cells directly from heart biopsies. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2010;49:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng K, Li T-S, Malliaras K, Davis DR, Zhang Y, Marban E. Magnetic targeting enhances engraftment and functional benefit of iron-labeled cardiosphere-derived cells in myocardial infarction. Circulation Research. 2010;106:1570–1581. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S-T, White AJ, Matsushita S, Malliaras K, Steenbergen C, Zhang Y, Li T-S, Terrovitis J, Yee K, Simsir S, Makkar R, Marban E. Intramyocardial injection of autologous cardiospheres or cardiosphere-derived cells preserves function and minimizes adverse ventricular remodeling in pigs with heart failure post-myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;57:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Lee A, Huang M, Chun H, Chung J, Chu P, Hoyt G, Yang P, Rosenberg J, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Imaging survival and function of transplanted cardiac resident stem cells. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53:1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, Leppo MK, Hare JM, Messina E, Giacomello A, Abraham MR, Marban E. Regenerative potential of cardiosphere-derived cells expanded from percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Circulation. 2007;115:896–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipinski MJ, Biondi-Zoccai GGL, Abbate A, Khianey R, Sheiban I, Bartunek J, Vanderheyden M, Kim H-S, Kang H-J, Strauer BE, Vetrovec GW. Impact of intracoronary cell therapy on left ventricular function in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: A collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Latif A, Bolli R, Tleyjeh IM, Montori VM, Perin EC, Hornung CA, Zuba-Surma EK, Al-Mallah M, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow-derived cells for cardiac repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D'Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, Beache GM, Wagner SG, Leri A, Hosoda T, Sanada F, Elmore JB, Goichberg P, Cappetta D, Solankhi NK, Fahsah I, Rokosh DG, Slaughter MS, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): Initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. The Lancet. 2011;378:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Schachinger V, Aicher A, Dobert N, Rover R, Diener J, Fichtlscherer S, Assmus B, Seeger FH, Menzel C, Brenner W, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Pilot trial on determinants of progenitor cell recruitment to the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2008;118:1425–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.777102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penicka M, Lang O, Widimsky P, Kobylka P, Kozak T, Vanek T, Dvorak J, Tintera J, Bartunek J. One-day kinetics of myocardial engraftment after intracoronary injection of bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with acute and chronic myocardial infarction. Heart. 2007;93:837–841. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.091934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goussetis E, Manginas A, Koutelou M, Peristeri I, Theodosaki M, Kollaros N, Leontiadis E, Theodorakos A, Paterakis G, Karatasakis G, Cokkinos DV, Graphakos S. Intracoronary infusion of CD133+ and CD133−CD34+ selected autologous bone marrow progenitor cells in patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy: Cell isolation, adherence to the infarcted area, and body distribution. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2279–2283. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraitchman DL, Heldman AW, Atalar E, Amado LC, Martin BJ, Pittenger MF, Hare JM, Bulte JWM. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;107:2290–2293. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070931.62772.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill JM, Dick AJ, Raman VK, Thompson RB, Yu Z-X, Hinds KA, Pessanha BSS, Guttman MA, Varney TR, Martin BJ, Dunbar CE, McVeigh ER, Lederman RJ. Serial cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of injected mesenchymal stem cells. Circulation. 2003;108:1009–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084537.66419.7A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaghoubi SS, Jensen MC, Satyamurthy N, Budhiraja S, Paik D, Czernin J, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive detection of therapeutic cytolytic T cells with 18F-FHBG PET in a patient with glioma. Nat Clin Prac Oncol. 2009;6:53–58. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tjuvajev JG, Stockhammer G, Desai R, Uehara H, Watanabe K, Gansbacher B, Blasberg RG. Imaging the expression of transfected genes in vivo. Cancer Research. 1995;55:6126–6132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambhir SS, Bauer E, Black ME, Liang Q, Kokoris MS, Barrio JR, Iyer M, Namavari M, Phelps ME, Herschman HR. A mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase reporter gene shows improved sensitivity for imaging reporter gene expression with positron emission tomography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:2785–2790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najjar AM, Nishii R, Maxwell DS, Volgin A, Mukhopadhyay U, Bornmann WG, Tong W, Alauddin M, Gelovani JG. Molecular-genetic PET imaging using an HSV1-tk mutant reporter gene with enhanced specificity to acycloguanosine nucleoside analogs. The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2009;50:409–416. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.058735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ponomarev V, Doubrovin M, Shavrin A, Serganova I, Beresten T, Ageyeva L, Cai C, Balatoni J, Alauddin M, Gelovani J. A human-derived reporter gene for noninvasive imaging in humans: Mitochondrial thymidine kinase type 2. The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:819–826. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.036962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goumans MJ, de Boer TP, Smits AM, van Laake LW, van Vliet P, Metz CH, Korfage TH, Kats KP, Hochstenbach R, Pasterkamp G, Verhaar MC, van der Heyden MA, de Kleijn D, Mummery CL, van Veen TA, Sluijter JP, Doevendans PA. TGF-beta1 induces efficient differentiation of human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells into functional cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cell Res. 2007;1:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smits AM, van Vliet P, Metz CH, Korfage T, Sluijter JP, Doevendans PA, Goumans MJ. Human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells differentiate into functional mature cardiomyocytes: An in vitro model for studying human cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Vliet P, Roccio M, Smits AM, van Oorschot AA, Metz CH, van Veen TA, Sluijter JP, Doevendans PA, Goumans MJ. Progenitor cells isolated from the human heart: A potential cell source for regenerative therapy. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:163–169. doi: 10.1007/BF03086138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits AM, van Vliet P, Metz CH, Korfage T, Sluijter JPG, Doevendans PA, Goumans M-J. Human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells differentiate into functional mature cardiomyocytes: An in vitro model for studying human cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Protocols. 2009;4:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black ME, Newcomb TG, Wilson HM, Loeb LA. Creation of drug-specific herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase mutants for gene therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996;93:3525–3529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balzarini J, Liekens S, Solaroli N, El Omari K, Stammers DK, Karlsson A. Engineering of a single conserved amino acid residue of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase allows a predominant shift from pyrimidine to purine nucleoside phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:19273–19279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaghoubi SS, Couto MA, Chen C-C, Polavaram L, Cui G, Sen L, Gambhir SS. Preclinical safety evaluation of 18F-FHBG: A pet reporter probe for imaging herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase (HSV1-tk) or mutant HSV1-sr39tk's expression. The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2006;47:706–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu JC. Molecular imaging: Antidote to cardiac stem cell controversy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52:1661–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li T-S, Gerstenblith G, Messina E, Giacomello A, Marban E. Relative roles of direct regeneration versus paracrine effects of human cardiosphere-derived cells transplanted into infarcted mice. Circulation Research. 2010;106:971–980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Oorschot AAM, Smits AM, Pardali E, Doevendans PA, Goumans M-J. Low oxygen tension positively influences cardiomyocyte progenitor cell function. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:2723–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bearzi C, Rota M, Hosoda T, Tillmanns J, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Yasuzawa-Amano S, Trofimova I, Siggins RW, LeCapitaine N, Cascapera S, Beltrami AP, D'Alessandro DA, Zias E, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Michler RE, Bolli R, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P. Human cardiac stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:14068–14073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis DR, Zhang Y, Smith RR, Cheng K, Terrovitis J, Malliaras K, Li T-S, White A, Makkar R, Marban E. Validation of the cardiosphere method to culture cardiac progenitor cells from myocardial tissue. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bu L, Jiang X, Martin-Puig S, Caron L, Zhu S, Shao Y, Roberts DJ, Huang PL, Domian IJ, Chien KR. Human ISL1 heart progenitors generate diverse multipotent cardiovascular cell lineages. Nature. 2009;460:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature08191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Thomson LEJ, Berman D, Czer LSC, Marb·n L, Mendizabal A, Johnston PV, Russell SD, Schuleri KH, Lardo AC, Gerstenblith G, Marban E. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): A prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. The Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Bogt KE, Sheikh AY, Schrepfer S, Hoyt G, Cao F, Ransohoff KJ, Swijnenburg RJ, Pearl J, Lee A, Fischbein M, Contag CH, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Comparison of different adult stem cell types for treatment of myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2008;118:S121–129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.759480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheikh AY, Lin SA, Cao F, Cao Y, van der Bogt KE, Chu P, Chang CP, Contag CH, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Molecular imaging of bone marrow mononuclear cell homing and engraftment in ischemic myocardium. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2677–2684. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao F, Wagner RA, Wilson KD, Xie X, Fu J-D, Drukker M, Lee A, Li RA, Gambhir SS, Weissman IL, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Transcriptional and functional profiling of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Police S, O'Sullivan C, Collins L, Chen Y, Minami E, Gill EA, Ueno S, Yuan C, Gold J, Murry CE. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotech. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer KM, Cottage CT, Wu W, Din S, Gude NA, Avitabile D, Quijada P, Collins BL, Fransioli J, Sussman MA. Enhancement of myocardial regeneration through genetic engineering of cardiac progenitor cells expressing Pim-1 kinase. Circulation. 2009;120:2077–2087. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.884403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen PK, Lan F, Wang Y, Wu JC. Imaging: Guiding the clinical translation of cardiac stem cell therapy. Circulation Research. 2011;109:962–979. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.242909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.