Abstract

Our previous results demonstrated that the apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) mimetic peptides L-4F and L-5F inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor production and tumor angiogenesis. The present study was designed to test whether apoA-I mimetic peptides inhibit the expression and activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), which plays a critical role in the production of angiogenic factors and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry staining was used to examine the expression of HIF-1α in tumor tissues. Immunoblotting, real-time polymerase chain reaction, immunofluorescence, and luciferase activity assays were used to determine the expression and activity of HIF-1α in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Immunohistochemistry staining demonstrated that L-4F treatment dramatically decreased HIF-1α expression in mouse ovarian tumor tissues. L-4F inhibited the expression and activity of HIF-1α induced by low oxygen concentration, cobalt chloride (CoCl2, a hypoxia-mimic compound), lysophosphatidic acid, and insulin in two human ovarian cancer cell lines, OV2008 and CAOV-3. L-4F had no effect on the insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt, but inhibited the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p70s6 kinase, leading to the inhibition of HIF-1α synthesis. Pretreatment with L-4F dramatically accelerated the proteasome-dependent protein degradation of HIF-1α in both insulin- and CoCl2-treated cells. The inhibitory effect of L-4F on HIF-1α expression is in part mediated by the reactive oxygen species-scavenging effect of L-4F. ApoA-I mimetic peptides inhibit the expression and activity of HIF-1α in both in vivo and in vitro models, suggesting the inhibition of HIF-1α may be a critical mechanism responsible for the suppression of tumor progression by apoA-I mimetic peptides.

Introduction

Because of the lack of tests to diagnose ovarian cancer at an early stage and the absence of effective therapeutic strategies, more than 70% of patients are diagnosed with late-stage disease and a 5-year survival rate of only 50%. We reported previously that serum apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) levels are significantly decreased in patients with ovarian cancer, and apoA-I could be used as a biomarker for the detection of early-stage ovarian cancer (Kozak et al., 2003, 2005; Su et al., 2007). Our results demonstrated that the overexpression of apoA-I inhibits tumor growth and improves survival in a mouse ovarian cancer model (Su et al., 2010). We further showed that apoA-I mimetic peptides (18 amino acids in length compared with 243 amino acids for apoA-I) inhibited tumor growth similar to apoA-I overexpression in mouse models of ovarian cancer (Su et al., 2010).

ApoA-I mimetic peptides do not have sequence homology to apoA-I. However, these peptides have the capacity to form class A amphipathic helixes similar to those found in apoA-I and mimic lipid binding properties of apoA-I, producing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects (Navab et al., 2005, 2006; Shah and Chyu, 2005; Getz et al., 2009). Based on the number of hydrophobic phenylalanine (F) residues in the sequence, the peptides are named 2F, 3F, 4F, 5F, 6F, and 7F. To account for the balance between solubility in an aqueous environment and the ability to interact with lipids, we have used both 4F and 5F in cancer studies (Su et al., 2010). Our data showed that L-4F and L-5F (L standing for L amino acids) significantly inhibit tumor growth in a mouse ovarian cancer model (Su et al., 2010). Tumor angiogenesis plays a critical role in the growth and progression of solid tumors, including ovarian cancer (Folkman, 1971; Hanahan and Folkman, 1996; Carmeliet and Jain, 2000). Among the angiogenic factors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is involved in every step of new vessel formation, including the proliferation, migration, invasion, tube formation of endothelial cells, and recruitment of various types of angiogenesis-associated cells, including VEGF receptor 1-positive cells and endothelial progenitor cells (Rafii et al., 2002; Adams and Alitalo, 2007; Ellis and Hicklin, 2008). More recently, we showed that the suppression of tumor growth is mediated, at least in part, by inhibition of the production of VEGF and subsequent tumor angiogenesis (Gao et al., 2011).

Expression and activity of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is crucial for the production of VEGF and other angiogenic factors in tumor tissues. HIF-1 is a heterodimeric transcription factor that consists of a constitutively expressed HIF-1β and an inducible α-subunit, HIF-1α. When tumor tissues overgrow, tumor cells located more than 100 μm from vessels are under hypoxic conditions. Because of the oxygen-dependent nature of HIF-1α degradation, low oxygen concentration leads to decreases of protein degradation, resulting in HIF-1α accumulation. On the other hand, some hormones and growth factors, including insulin and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), also promote protein accumulation of HIF-1α by activating various signaling pathways under normoxic conditions (Cao et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2006, 2009). HIF-1α binds to HIF-1β, translocates into the nucleus, and contributes to tumorigenesis through the transcriptional activation of downstream genes, the protein products of which are required for angiogenesis (including VEGF and angiopoietins), glucose transport, and cell survival (Semenza, 2003; Pouysségur and Mechta-Grigoriou, 2006; Pouysségur et al., 2006). In this article, we examined the effect of L-4F and L-5F on the expression and activity of HIF-1α in human ovarian cancer cell lines and mouse ovarian tumor tissues to delineate the mechanisms behind the antiangiogenic and antitumorigenic effects of apoA-I mimetic peptides.

Materials and Methods

Cells, Cell Culture, and Reagents.

OV2008 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 1 × minimal essential medium nonessential amino acid solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and insulin (0.25 U/ml) (Invitrogen). CAOV-3 cells were cultured in complete media consisting of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with high glucose and l-glutamine (2 mM), 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and insulin (0.02 U/ml). To create hypoxic conditions, cells were transferred to a hypoxic chamber (model 3130; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), where they were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2, 1% O2, and 94% N2.

L-4F (the peptide Ac-D-W-F-K-A-F-Y-D-K-V-A-E-K-F-K-E-A-F-NH2 synthesized from all L amino acids) was dissolved in water at 1 mg/ml (freshly prepared every time) and used between 1 and 10 μg/ml. L-5F was synthesized by Peptisyntha Inc. (Torrance, CA), dissolved in ABCT buffer (50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7.0, containing 0.1 mg/ml Tween 20) at 1 mg/ml, and diluted to the required concentrations before use. Cobalt chloride (CoCl2), insulin, cycloheximide (CHX), and N-(benzyloxycarbonyl)leucinylleucinylleucinal-Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al (MG-132) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). LPA (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) in chloroform was dried as recommended by the manufacturer, dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 20 mM as a stock solution, and diluted to the required concentrations in the corresponding cell culture media before use.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from cells by using a PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). The quantity and quality of RNA were assessed by using a SmartSpec 3000 Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). cDNA was synthesized by using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCRs were performed by using the CFX96 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The cycling conditions were as follows: 3 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 95°C, 10 s; 60°C, 10 s; 72°C, 30 s followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Each 25-μl reaction contained 0.4 μg of cDNA, 12.5 μl of SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and 250 nM forward and reverse primers in nuclease-free water. Primers used were: HIF-1α, 5′-TCC AGT TAC GTT CCT TCG ATC A-3′ and 5′-TTT GAG GAC TTG CGC TTT CA-3′, VEGF, 5′-CGG CGA AGA GAA GAG ACA CA-3′ and 5′-GGA GGA AGG TCA ACC ACT CA-3′; glucose transporter-1, 5′-CGG GCC AAG AGT GTG CTA AA-3′ and 5′-TGA CGA TAC CGG AGC CAA TG-3′; aldolase-A, 5′-TGC TAC TAC CAG CAC CAT GC-3′ and 5′-ATG CTC CCA GTG GAC TCA TC-3′; and GAPDH, 5′-GGA AGG TGA AGG TCG GAG TCA-3′ and 5′-GTC ATT GAT GGC AAC AAT ATC CAC T-3′. The experiment was repeated once with triplicate measurements in each experiment.

Western Blot Analysis.

Western blot analyses were performed as described previously (Gao et al., 2011). In brief, cell lysates were collected in a lysis buffer containing 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 μM sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, loaded onto 4 to 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and incubated with the appropriate antibodies. Anti-pThr202/Tyr204-Erk, anti-Erk, anti-pThr389-p70 S6 kinase, anti-p70 S6 kinase, anti-pSer473-Akt, and anti-Akt antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); mouse anti-human HIF-1α antibody was purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA); rabbit anti-mouse HIF-1α antibody was purchased from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA); and anti-GAPDH antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA).

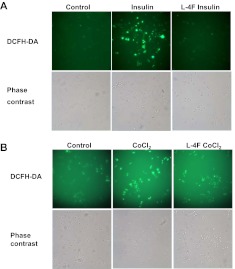

Measurement of Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species.

As described previously (Zhou et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009), OV2008 cells were plated onto a glass slip (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 24-well plate at 4 × 104 cells per well, cultured overnight in normal cultured condition, starved in serum-free media overnight, and treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h. Then, dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, 10 μM) and insulin (200 nM)/CoCl2 (100 μM) were added and incubated with the cells for an additional 0.5 h. The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Hypoxia Response Element Reporter Assay.

In brief, OV2008 cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells per well in a six-well plate and grown in complete media overnight. Then, pGL3-Epo-hypoxia response element (HRE)-Luc plasmid was transfected into cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24 h, cells were starved overnight and subjected to L-4F treatment in the presence or absence of stimulators. A reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) was used for the measurement of luciferase activity.

Immunofluorescence Staining of HIF-1α.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously (Lee et al., 2006). In brief, OV2008 cells were plated onto a glass slip (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 24-well plates at 4 × 104 cells per well and grown in complete medium overnight. After starvation overnight, cells were subjected to L-4F treatment in the presence or absence of stimulators. Then, cells were fixed in 4% neutral buffered formaldehyde for 25 min at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and blocked with 10% normal goat serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.3 M glycine prepared in PBS for 1 h. Cells were incubated with mouse anti-HIF-1α (1:200) overnight at 4°C and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) for 1 h. Finally, cells were covered with VectaMount solution containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70).

In Vivo Tumor Model.

Nine-week-old C57BL/6J female mice were given a 0.5-ml subcutaneous injection of 5 × 106 ID8 cells prepared as a single cell suspension in PBS mixed with an equal volume of cold Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After 2 weeks, mice started to receive scrambled 4F peptide (sc-4F) or L-4F (10 mg/kg) by subcutaneous injection at a site distant from the site where the ID8 cells were injected daily for 3 weeks. After 3 weeks, the mice were sacrificed for tumor collection and further analyses.

Immunohistochemistry Staining.

Frozen tumor tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm and fixed with cold acetone for 10 min at −20°C. The sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum and 4% bovine serum albumin prepared in PBS for 3 h and immediately incubated with rabbit anti-mouse polyclonal HIF-1α antibody (1:200) (Abcam Inc.) or rat anti-mouse monoclonal CD31 antibody (1:25) (Abcam Inc.) overnight at 4°C. The sections were then incubated with corresponding biotinylated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature followed by incubation with Vectastain ABC Elite reagents (Vector Laboratories) to visualize the staining. Finally, sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and coverslipped with VectaMount solution (Vector Laboratories).

Statistics.

Data are shown as mean ± S.D. for each group. We performed statistical analyses by unpaired t test. Results for all tests were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

L-4F Inhibits HIF-1α Expression and Angiogenesis In Vivo.

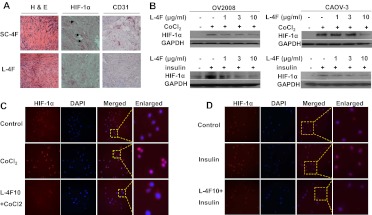

Our previous data showed that the apoA-I mimetic peptides L-4F and L-5F inhibited tumor growth and angiogenesis in an immunocompetent mouse model of ovarian cancer that uses the epithelial cancer cell line ID8 (Gao et al., 2011). Given the importance of HIF-1α in the production of VEGF, a critical growth factor implicated in tumor angiogenesis, we first examined the effect of L-4F on HIF-1α expression by using the same model. Immunohistochemistry staining showed that L-4F treatment decreased HIF-1α expression in tumor tissues compared with a control peptide (sc-4F)-treated group (Fig. 1A). Consistent with our previous report (Gao et al., 2011), we observed a reduction in the number of vessels in L-4F-treated mice compared with the control group (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The ApoA-I mimetic peptide L-4F inhibits HIF-1α expression in vivo and in vitro. A, an apoA-I mimetic peptide, L-4F, inhibits HIF-1α expression and angiogenesis in vivo. Flank tumors were established in wild-type C57BL/6J mice as described under Materials and Methods. Two weeks after tumor growth, mice were treated with scrambled peptide (sc-4F) or L-4F (10 mg/kg s.c., daily injection) for 3 weeks. Frozen sections (5 μm) from dissected tumors were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (left), HIF-1α staining (center), and CD31 staining (right). Analysis was done from four randomly selected fields per slide (n = 4 mice per group). Representative figures are shown at 400× magnification. Arrows indicate HIF-1α-positive staining. B, pretreatment of L-4F inhibits CoCl2- and insulin-induced HIF-1α expression in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Cells were treated with vehicle or different concentrations of L-4F (1, 3, and 10 μg/ml) for 1 h, and the indicated stimulators were added for another 4 h. Left, pretreatment of L-4F inhibits CoCl2- and insulin-induced HIF-1α expression in OV2008 cells. Right, pretreatment of L-4F inhibits CoCl2- and insulin-induced HIF-1α expression in CAOV-3 cells. C and D, L-4F decreases CoCl2-induced (C) and insulin-induced (D) nuclear expression of HIF-1α in OV2008 cells. Cells were immunostained with a mouse monoclonal anti-HIF-1α primary antibody and a goat anti-mouse IgG labeled with Alexa Fluor 568 (red fluorescence) as the secondary antibody. DAPI was used to stain nuclei (blue). Images are shown at the original magnification of 200×. Dotted line and boxes show the area where the enlarged images originated. Representative photographs of two independent experiments with similar results are shown. The concentrations of stimulators used were: CoCl2, 100 μM, and insulin, 200 nM.

L-4F and L-5F Inhibits HIF-1α Expression in Cell Cultures.

To examine whether L-4F inhibits HIF-1α expression in cells under hypoxic conditions, low oxygen concentration (1% O2) and a hypoxia mimetic chemical, CoCl2, were used to induce HIF-1α expression in a human ovarian cancer cell line, OV2008. Western blot analysis showed that L-4F dose-dependently suppressed hypoxia-induced HIF-1α protein expression (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. 1B). Similar results were observed when OV2008 cells were treated with insulin at 100 nM (data not shown) and 200 nM (Fig. 1B) and LPA at 20 μM (Supplemental Fig. 1B).

To further confirm the inhibitory role of L-4F in HIF-1α expression, two other human ovarian cancer cell lines, CAOV-3 and SKOV3, were studied. Consistent with the data for OV2008 cells, L-4F dose-dependently inhibited CoCl2- and insulin-induced HIF-1α expression in both CAOV-3 cells (Fig. 1A) and SKOV3 cells (data not shown).

To examine whether the inhibitory effect on HIF-1α is specific to L-4F, another apoA-I mimetic peptide, L-5F, was used to treat OV2008 cells. Similar to L-4F treatment, L-5F dose-dependently inhibited low oxygen- and CoCl2-stimulated HIF-1α expression (Supplemental Fig. 1C).

As a transcription factor, HIF-1α functions in nuclei and activates expression of downstream genes. Immunofluorescence staining was used to examine the effect of L-4F on the nuclear levels of HIF-1α protein. CoCl2 and insulin treatments greatly increased the accumulation of HIF-1α in nuclei of OV2008 cells, and pretreatment of L-4F dramatically reversed these effects (Fig. 1, C and D).

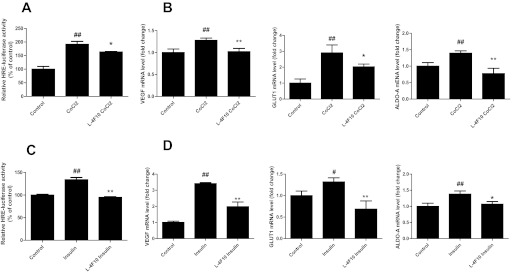

Inhibition of HIF-1α-Dependent Gene Transcription by L-4F.

To determine whether L-4F inhibits HIF-1α-driven gene transcription, OV2008 cells were transfected with a HRE containing luciferase reporter plasmid. L-4F treatment significantly inhibited CoCl2- and insulin-mediated induction of luciferase activity (Fig. 2, A and C). Moreover, L-4F treatment abrogated CoCl2- and insulin-induced increase in mRNA levels of HIF-1α target genes including VEGF, glucose transporter 1, and aldolase-A (Fig. 2, B and D), suggesting that L-4F inhibits both HIF-1α protein expression and activity.

Fig. 2.

HIF-1α target gene expression is inhibited by L-4F in OV2008 cells. A, CoCl2-stimulated HRE reporter gene transcription is inhibited by pretreatment of L-4F. OV2008 cells were transfected with pGL3-Epo-HRE-Luc plasmid and grown in complete growth media for 24 h. After an overnight starvation, cells were first treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h and then treated with CoCl2 (100 μM) for an additional 6 h. Luciferase activity was determined as described under Materials and Methods. B, L-4F inhibits expression of HIF-1α target genes in CoCl2-treated cells. After serum starvation overnight, OV2008 cells were treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h and then treated with CoCl2 (100 μM) for an additional 6 h. Total RNA was isolated, and the expression of VEGF, glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), and aldolase-A (ALDO-A) mRNA levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR. GAPDH was used for normalization. C, insulin-stimulated HRE reporter gene transcription is inhibited by the pretreatment of L-4F. OV2008 cells were transfected with pGL3-Epo-HRE-Luc plasmid and grown in complete growth media for 24 h. After starvation overnight, cells was treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h and then treated with insulin (200 nM) for an additional 16 h. Luciferase activity was determined as described under Materials and Methods. D, L-4F inhibits the expression of HIF-1α target genes in insulin-treated cells. After serum starvation overnight, OV2008 cells were treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h and then treated with insulin (200 nM) for an additional 16 h. Total RNA was isolated and the expression of VEGF, glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), and aldolase-A (ALDO-A) mRNA levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR. GAPDH was used for normalization. #, p < 0.05, compared with the corresponding control group. ##, p < 0.01, compared with the corresponding control group. *, p < 0.05, compared with the corresponding CoCl2- or insulin-treated groups. **, p < 0.01, compared with the corresponding CoCl2- or insulin-treated groups. n = 3 for each group.

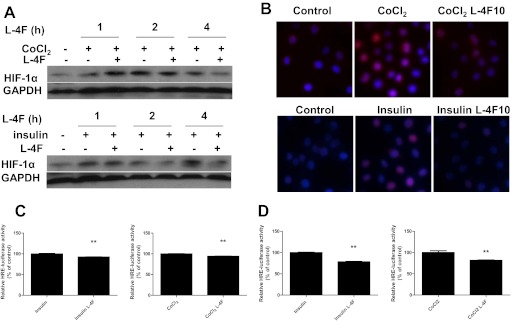

Post-Treatment of L-4F Decreases HIF-1α Protein Level and Activity in CoCl2- and Insulin-Treated OV2008 Cells.

Because HIF-1α expression is elevated in advanced tumors that are presented clinically, we next examined whether L-4F given after hypoxia or growth factor stimulation inhibited HIF-1α expression. OV2008 cells were stimulated first with CoCl2 or insulin for 3 h (Supplemental Fig. 2) or 24 h (Fig. 3), and then treated with L-4F for various durations. Post-treatment of L-4F significantly decreased HIF-1α expression in OV2008 cells (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. 2A). Immunofluorescence analysis showed decreased nuclear expression of HIF-1α by post-treatment of L-4F (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. 2B). Moreover, down-regulation of HIF-1α protein in the nucleus correlated with the inhibition of the transcription of downstream HIF-1α target genes (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Fig. 2C).

Fig. 3.

Post-treatment of L-4F decreases HIF-1α protein level and activity in CoCl2- and insulin-treated OV2008 cells. Cells were treated with CoCl2 (100 μM) or insulin (200 nM) for 24 h and then treated with vehicle or L-4F (10 μg/ml) for an additional 1, 2, or 4 h. A, post-treatment of L-4F at 10 μg/ml decreases HIF-1α protein level in CoCl2- and insulin-treated OV2008 cells. B, post-treatment of L-4F at 10 μg/ml for 4 h decreases CoCl2- and insulin-induced increases of nuclear levels of HIF-1α in OV2008 cells. Cells were immunostained with a mouse monoclonal anti-HIF-1α primary antibody and a goat anti-mouse IgG labeled with Alexa Fluor 568 (red fluorescence) as the secondary antibody. DAPI was used to stain nuclei (blue). Images are shown at the original magnification of 400×. Representative photographs of two independent experiments with similar results are shown. C and D, inhibition of HRE reporter gene transcription in CoCl2- and insulin-treated cells by post-treatment of L-4F. OV2008 cells were transfected with pGL3-Epo-HRE-Luc plasmid and grown in complete growth media for 24 h. After starvation overnight, cells was treated with CoCl2 (100 μM) or insulin (200 nM) for 24 h and then treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for an additional 4 h (C) or 24 h (D). Luciferase activity was determined as described under Materials and Methods. **, p < 0.01, compared with the corresponding CoCl2- or insulin-treated groups. n = 3 for each group.

L-4F Does Not Affect HIF-1α Transcription.

To determine whether L-4F affects HIF-1α synthesis at the transcriptional level, we quantified HIF-1α mRNA content to determine whether a change in HIF-1α mRNA level precedes that of protein. Real-time RT-PCR analyses indicated that L-4F had no effect on the basal level of HIF-1α mRNA (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Moreover, consistent with previous reports (Semenza, 2003; Pouysségur et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2009), low oxygen and insulin did not affect HIF-1α gene transcription (Supplemental Fig. 3B), suggesting that the regulation of HIF-1α protein expression by L-4F occurs at the post-transcriptional level.

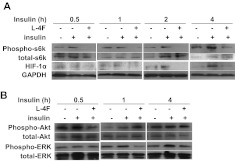

L-4F inhibits S6 Kinase Phosphorylation in an ERK-Dependent Manner.

Activation of S6 kinase is critical for insulin-induced de novo synthesis of HIF-1α (Semenza, 2003). To determine the molecular mechanism of HIF-1α inhibition by L-4F, we tested whether L-4F affects the insulin-stimulated protein synthesis of HIF-1α. Our data showed that L-4F at 10 μg/ml prevented phosphorylation of S6 kinase (Fig. 4A). S6 kinase phosphorylation is regulated by the activation of upstream signaling molecules ERK and Akt. As shown in Fig. 4B, L-4F inhibited activation of ERK1/2, but had no effect on the phosphorylation of Akt, except at 0.5 h, suggesting that the inhibition of S6 kinase activation may most likely be a result of the suppression of ERK phosphorylation. It is noteworthy that we did not observe an effect of CoCl2 on the phosphorylation of ERK, Akt, and S6 kinase in OV2008 cells (Supplemental Fig. 4A). This result is not surprising because CoCl2 treatment mimics hypoxia, which leads to decreases in HIF-1α protein degradation (Pouysségur and Mechta-Grigoriou, 2006).

Fig. 4.

Effect of L-4F on the insulin-stimulated activation of downstream signaling molecules in OV2008 cells. After an overnight starvation, OV2008 cells were treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h, and insulin was added at a final concentration of 200 nM. Cell lysates were collected at various time points and subjected to Western blot analysis. A, L-4F inhibits insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of p70s6 kinase and subsequent HIF-1α expression in OV2008 cells. B, effect of L-4F on insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt in OV2008 cells.

L-4F Treatment Promotes Proteasome-Dependent Protein Degradation.

We next examined whether L-4F changes the stability of the HIF-1α protein. CHX, a compound that prevents new protein synthesis, was used to inhibit de novo HIF-1α protein synthesis. Our data showed that OV2008 cells treated with CHX in combination with insulin exhibited a gradual decrease in HIF-1α as a function of time, and simultaneous L-4F treatment accelerated the degradation of HIF-1α protein (Fig. 5A). We observed a similar effect of L-4F on CoCl2-treated OV2008 cells (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Furthermore, MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, led to a reversal of the inhibitory effect of L-4F on insulin-mediated HIF-1α expression (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that L-4F inhibits insulin- and CoCl2-induced HIF-1α expression and activity in ovarian cancer cells, in part, by accelerating the degradation of HIF-1α protein.

Fig. 5.

Effect of L-4F on HIF-1α protein stability in OV2008 cells. A, left, pretreatment of L-4F promotes HIF-1α degradation in OV2008 cells. After an overnight starvation, OV2008 cells were treated with insulin (200 nM) for 3 h, L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h, and CHX (20 μg/ml) for various durations. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis. Representative data from three independent experiments with similar results are shown. Right, L-4F treatment promotes HIF-1α degradation in OV2008 cells. After an overnight starvation, OV2008 cells were treated with insulin (200 nM) for 3 h and then treated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) and CHX (20 μg/ml) at the same time. Cell lysates were collected at various time points and subjected to Western blot analysis. Representative data from three independent experiments with similar results are shown. B, effect of pretreatment of L-4F on proteasome-mediated degradation of HIF-1α in insulin-treated OV2008 cells. After an overnight starvation, OV2008 cells were treated with MG-132 (10 μM) for 3 h, L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h, and insulin (200 nM) for an additional 4 h. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis. Representative data from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

Inhibition of Insulin- and CoCl2-Induced ROS Production by L-4F Treatment.

It is reported that insulin treatment (Zhou et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009) and CoCl2 treatment (Chandel et al., 2000; Griguer et al., 2006) significantly increase cellular ROS levels, which subsequently promotes the synthesis of HIF-1α and inhibits its degradation. As shown by dichlorofluorescein oxidation assay (Fig. 6), treatment of insulin and CoCl2 led to an increase of cellular ROS levels in OV2008 cells. Pretreatment of L-4F dramatically prevented the cellular ROS production induced by insulin and CoCl2 (Fig. 6), suggesting that the inhibitory role of L-4F on HIF-1α expression may be a result of the inhibition of ROS accumulation.

Fig. 6.

Effect of L-4F on CoCl2- and insulin-stimulated ROS production. OV2008 cells were pretreated with L-4F (10 μg/ml) for 1 h, and then treated with insulin (200 nM)/CoCl2 (100 μM) and DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 30 min. After washing cells twice with PBS, images of cells were captured with a fluorescence microscope. Representative figures are shown at the original magnification of 200×. A, L-4F inhibits insulin-stimulated ROS production in OV2008 cells. B, L-4F inhibits CoCl2-stimulated ROS production in OV2008 cells.

Discussion

HIF-1 is a key cellular survival protein under hypoxia and is associated with tumor progression and metastasis in various solid tumors (Seeber et al., 2011). Targeting HIF-1α could be an attractive anticancer therapeutic strategy (Semenza, 2003; Belozerov and Van Meir, 2005; Seeber et al., 2011). Expression of HIF-1α is increased by both hypoxic and nonhypoxic stimuli. Low oxygen concentration or treatment with CoCl2, a hypoxic mimetic compound, inhibits the degradation of HIF-1α and increases HIF-1α protein stability and accumulation. Some growth factors, including insulin and LPA, also promote post-transcriptional protein synthesis and up-regulate the expression and activity of HIF-1α (Semenza, 2003; Pouysségur and Mechta-Grigoriou, 2006; Pouysségur et al., 2006). In this article, we demonstrate that: 1) L-4F inhibits HIF-1α expression in mouse tumor tissues (Fig. 1A); 2) pretreatment and post-treatment of L-4F and L-5F decrease low oxygen-, CoCl2-, insulin-, and LPA-induced expression and nuclear levels of HIF-1α in human ovarian cancer cell lines (Figs. 1 and 3; Supplemental Figs. 1 and 2); and 3) L-4F inhibits CoCl2- and insulin-stimulated expression of HRE-driven reporter gene and activation of HIF-1α target genes (Figs. 2 and 3; Supplemental Fig. 2). Real-time RT-PCR analyses indicated that L-4F has no effect on HIF-1α gene transcription in OV2008 cells (Supplemental Fig. 3), indicating that the regulation of HIF-1α protein by L-4F occurs at the post-transcriptional level.

There is compelling evidence that ROS are key players in the regulation of HIF-1α under normoxia as well as hypoxia (Pouysségur and Mechta-Grigoriou, 2006). As reported previously, treatment of cells with low oxygen concentration (Chandel et al., 2000; Guzy et al., 2005; Guzy and Schumacker, 2006), CoCl2 (Chandel et al., 2000; Griguer et al., 2006), insulin (Zhou et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009), and LPA (Chen et al., 1995; Saunders et al., 2010) lead to ROS generation. ROS production is critical for HIF-1α expression in cells, and removal of ROS impairs HIF-1α accumulation induced by hypoxia and insulin (Brunelle et al., 2005; Mansfield et al., 2005; Carnesecchi et al., 2006; Biswas et al., 2007). Ganapathy et al. (2012) reported that D-4F, an apoA-I mimetic peptide, significantly decreases the production of superoxide and H2O2 and improves the oxidative status on ID8 cells. However, it is unknown whether peptide treatment affects hypoxia- or growth factor-mediated ROS production. Here, we report that L-4F treatment dramatically inhibits insulin- and CoCl2-induced ROS production in OV2008 cells (Fig. 6). Furthermore, L-4F accelerated HIF-1α degradation in cancer cells exposed to insulin and CoCl2 (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. 4B). MG-132, a 26S proteasome inhibitor, reversed the inhibitory effect of L-4F on insulin-mediated HIF-1α expression (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these data demonstrate that L-4F decreases the protein stability of HIF-1α and inhibits the accumulation of transcriptionally active HIF-1α, at least in part, through its ROS-scavenging effect.

In an effort to find the molecular mechanism of HIF-1α inhibition, we determined whether L-4F affects the synthesis of HIF-1α protein. Insulin activates receptor tyrosine kinase and downstream signaling molecules, most notably S6 kinase, leading to increases of mRNA translation and de novo synthesis of HIF-1α (Treins et al., 2002; Semenza, 2003). L-4F inhibits insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of S6 kinase at various time points, resulting in a decrease of HIF-1α protein level (Fig. 4A). Further experiments showed that down-regulation of S6 kinase activity may be a result of the inhibition of the activation of ERK1/2, but not Akt (Fig. 4B). It is noteworthy that it is reported that ROS is involved in insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and S6 kinase, but not Akt (Zhou et al., 2007), indicating that ROS removal may also be involved in the inhibition of the de novo synthesis of HIF-1α by L-4F.

Previous reports showed that D-4F (an apoA-I mimetic peptide identical to L-4F but synthesized with all D amino acids) increases the expression and activity of two antioxidant enzymes, heme oxygenase 1 and extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD), in aorta from control and diabetic rats (Kruger et al., 2005). More recently, we also demonstrated that D-4F up-regulates the antioxidant enzyme Mn-SOD in ID8 cells, and knockdown of Mn-SOD results in the complete loss of antitumorigenic effects of D-4F in a mouse ovarian cancer model (Ganapathy et al., 2012). Because SOD activity modulates ROS production and cellular oxidative stress, induction of SOD may be an important part of the mechanism of action of apoA-I mimetic peptides.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that apoA-I mimetic peptides inhibit the expression and activity of HIF-1α both in vivo and in cell culture. The inhibition of HIF-1α may be a critical mechanism responsible for the suppression of tumor progression by apoA-I mimetic peptides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chintda Santiskulvong and Dr. Oliver Dorigo (University of California, Los Angeles, CA) for providing the CAOV-3 and OV2008 cell lines; and Dr. Xiaomeng Wu and Dr. Oliver Hankinson for providing the pGL3-Epo-HRE-Luc plasmid.

This work was supported by funds from the Women's Endowment, the Carl and Roberta Deutsch Family Foundation, the Joan English Fund for Women's Cancer Research, a VA Merit I Award (to R.F.-E.), the Ovarian Cancer Coalition, the Helen Beller Foundation, the Wendy Stark Foundation, the Sue and Mel Geleibter Family Foundation, Kelly Day, the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants HL-30568, HL-082823], and the Laubisch and M. K. Gray funds at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

The online version of this article (available at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

The online version of this article (available at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

- apoA-I

- apolipoprotein A-I

- HIF-1

- hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- CoCl2

- cobalt chloride

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- DAPI

- 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DCFH-DA

- dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HRE

- hypoxia response element

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- RT

- reverse transcription

- sc-4F

- scrambled 4F

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase

- MG-132

- N-(benzyloxycarbonyl)leucinylleucinylleucinal-Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Gao, Reddy, and Farias-Eisner.

Conducted experiments: Gao, Chattopadhyay, Grijalva, and Su.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Navab, Fogelman, Reddy, and Farias-Eisner.

Performed data analysis: Gao.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Gao, Reddy, and Farias-Eisner.

References

- Adams RH, Alitalo K. (2007) Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:464–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belozerov VE, Van Meir EG. (2005) Hypoxia inducible factor-1: a novel target for cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs 16:901–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Gupta MK, Chattopadhyay D, Mukhopadhyay CK. (2007) Insulin-induced activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 requires generation of reactive oxygen species by NADPH oxidase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292:H758–H766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle JK, Bell EL, Quesada NM, Vercauteren K, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, Scarpulla RC, Chandel NS. (2005) Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab 1:409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Fang J, Xia C, Shi X, Jiang BH. (2004) trans-3,4,5′-Trihydroxystibene inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 10:5253–5263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. (2000) Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 407:249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnesecchi S, Carpentier JL, Foti M, Szanto I. (2006) Insulin-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression is mediated by the NADPH oxidase NOX3. Exp Cell Res 312:3413–3424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Vander Heiden MG, Thompson CB, Schumacker PT. (2000) Redox regulation of p53 during hypoxia. Oncogene 19:3840–3848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Olashaw N, Wu J. (1995) Participation of reactive oxygen species in the lysophosphatidic acid-stimulated mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase activation pathway. J Biol Chem 270:28499–28502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. (2008) VEGF-targeted therapy: mechanisms of anti-tumour activity. Nat Rev Cancer 8:579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. (1971) Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med 285:1182–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathy E, Su F, Meriwether D, Devarajan A, Grijalva V, Gao F, Chattopadhyay A, Anantharamaiah GM, Navab M, Fogelman AM, et al. (2012) D-4F, an apoA-I mimetic peptide, inhibits proliferation and tumorigenicity of epithelial ovarian cancer cells by up-regulating the antioxidant enzyme MnSOD. Int J Cancer 130:1071–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Vasquez SX, Su F, Roberts S, Shah N, Grijalva V, Imaizumi S, Chattopadhyay A, Ganapathy E, Meriwether D, et al. (2011) L-5F, an apolipoprotein A-I mimetic, inhibits tumor angiogenesis by suppressing VEGF/basic FGF signaling pathways. Integr Biol (Camb) 3:479–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz GS, Wool GD, Reardon CA. (2009) Apoprotein A-I mimetic peptides and their potential anti-atherogenic mechanisms of action. Curr Opin Lipidol 20:171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griguer CE, Oliva CR, Kelley EE, Giles GI, Lancaster JR, Jr, Gillespie GY. (2006) Xanthine oxidase-dependent regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor in cancer cells. Cancer Res 66:2257–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, Simon MC, Hammerling U, Schumacker PT. (2005) Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab 1:401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Schumacker PT. (2006) Oxygen sensing by mitochondria at complex III: the paradox of increased reactive oxygen species during hypoxia. Exp Physiol 91:807–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Folkman J. (1996) Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 86:353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Amneus MW, Pusey SM, Su F, Luong MN, Luong SA, Reddy ST, Farias-Eisner R. (2003) Identification of biomarkers for ovarian cancer using strong anion-exchange ProteinChips: potential use in diagnosis and prognosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:12343–12348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Su F, Whitelegge JP, Faull K, Reddy S, Farias-Eisner R. (2005) Characterization of serum biomarkers for detection of early stage ovarian cancer. Proteomics 5:4589–4596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger AL, Peterson S, Turkseven S, Kaminski PM, Zhang FF, Quan S, Wolin MS, Abraham NG. (2005) D-4F induces heme oxygenase-1 and extracellular superoxide dismutase, decreases endothelial cell sloughing, and improves vascular reactivity in rat model of diabetes. Circulation 111:3126–3134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Park SY, Lee EK, Park CG, Chung HC, Rha SY, Kim YK, Bae GU, Kim BK, Han JW, et al. (2006) Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α is necessary for lysophosphatidic acid-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Clin Cancer Res 12:6351–6358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WH, Kim YW, Choi JH, Brooks SC, 3rd, Lee MO, Kim SG. (2009) Oltipraz and dithiolethione congeners inhibit hypoxia-inducible factor-1α activity through p70 ribosomal S6 kinase-1 inhibition and H2O2-scavenging effect. Mol Cancer Ther 8:2791–2802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield KD, Guzy RD, Pan Y, Young RM, Cash TP, Schumacker PT, Simon MC. (2005) Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from loss of cytochrome c impairs cellular oxygen sensing and hypoxic HIF-α activation. Cell Metab 1:393–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, Fogelman AM. (2006) Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides and their role in atherosclerosis prevention. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 3:540–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, Hama S, Hough G, Grijalva VR, Yu N, Ansell BJ, Datta G, Garber DW, et al. (2005) Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:1325–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouysségur J, Dayan F, Mazure NM. (2006) Hypoxia signalling in cancer and approaches to enforce tumour regression. Nature 441:437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouysségur J, Mechta-Grigoriou F. (2006) Redox regulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor. Biol Chem 387:1337–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafii S, Lyden D, Benezra R, Hattori K, Heissig B. (2002) Vascular and haematopoietic stem cells: novel targets for anti-angiogenesis therapy? Nat Rev Cancer 2:826–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JA, Rogers LC, Klomsiri C, Poole LB, Daniel LW. (2010) Reactive oxygen species mediate lysophosphatidic acid induced signaling in ovarian cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med 49:2058–2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber LM, Horrée N, Vooijs MA, Heintz AP, van der Wall E, Verheijen RH, van Diest PJ. (2011) The role of hypoxia inducible factor-1α in gynecological cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 78:173–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. (2003) Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 3:721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah PK, Chyu KY. (2005) Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides: potential role in atherosclerosis management. Trends Cardiovasc Med 15:291–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su F, Kozak KR, Imaizumi S, Gao F, Amneus MW, Grijalva V, Ng C, Wagner A, Hough G, Farias-Eisner G, et al. (2010) Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) and apoA-I mimetic peptides inhibit tumor development in a mouse model of ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:19997–20002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su F, Lang J, Kumar A, Ng C, Hsieh B, Suchard MA, Reddy ST, Farias-Eisner R. (2007) Validation of candidate serum ovarian cancer biomarkers for early detection. Biomark Insights 2:369–375 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Semenza GL, Van Obberghen E. (2002) Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 277:27975–27981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Liu LZ, Fu B, Hu X, Shi X, Fang J, Jiang BH. (2007) Reactive oxygen species regulate insulin-induced VEGF and HIF-1α expression through the activation of p70S6K1 in human prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 28:28–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.