Abstract

AIM: To investigate endoscopic and clinicopathologic characteristics of early gastric cancer (EGC) according to microsatellite instability phenotype.

METHODS: Data were retrospectively collected from a single tertiary referral center. Of 981 EGC patients surgically treated between December 2003 and October 2007, 73 consecutive EGC patients with two or more microsatellite instability (MSI) mutation [high MSI (MSI-H)] and 146 consecutive EGC patients with one or no MSI mutation (non-MSI-H) were selected. The endoscopic and clinicopathologic features were compared between the MSI-H and non-MSI-H EGC groups.

RESULTS: In terms of endoscopic characteristics, MSI-H EGCs more frequently presented with elevated pattern (OR 4.38, 95% CI: 2.40-8.01, P < 0.001), moderate-to-severe atrophy in the surrounding mucosa (OR 1.91, 95% CI: 1.05-3.47, P = 0.033), antral location (OR 3.99, 95% CI: 2.12-7.52, P < 0.001) and synchronous lesions, compared to non-MSI-H EGCs (OR 2.65, 95% CI: 1.16-6.07, P = 0.021). Other significant clinicopathologic characteristics of MSI-H EGC included predominance of female sex (OR 2.77, 95% CI: 1.53-4.99, P < 0.001), older age (> 70 years) (OR 3.30, 95% CI: 1.57-6.92, P = 0.002), better histologic differentiation (OR 2.35, 95% CI: 1.27-4.34, P = 0.007), intestinal type by Lauren classification (OR 2.34, 95% CI: 1.15-4.76, P = 0.019), absence of a signet ring cell component (OR 2.44, 95% CI: 1.02-5.86, P = 0.046), presence of mucinous component (OR 5.06, 95% CI: 1.27-20.17, P = 0.022), moderate-to-severe lymphoid stromal reaction (OR 3.95, 95% CI: 1.59-9.80, P = 0.003), and co-existing underlying adenoma (OR 2.66, 95% CI: 1.43-4.95, P = 0.002).

CONCLUSION: MSI-H EGC is associated with unique endoscopic and clinicopathologic characteristics including frequent presentation in protruded type, co-existing underlying adenoma, and synchronous lesions.

Keywords: Microsatellite instability, Early gastric cancer, Endoscopic characteristic, Advanced gastric cancer

INTRODUCTION

Microsatellites are simple repetitive DNA sequences that are scattered throughout the genome. Instability within these sequences is a marker of DNA mismatch repair deficiency[1]. The molecular mechanism of high microsatellite instability is the accumulation of frameshift mutations in the genes containing microsatellites within coding regions[2]. The resulting inactivation of these target genes is believed to contribute to tumor development and progression.

Previous research has focused on the analysis of microsatellite instability (MSI) in various cancers[3-5]. In colorectal cancer, high MSI (MSI-H) phenotypes are found in most cases of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancers and in 15% to 20% of sporadic colon cancers[6]. The clinicopathologic characteristics of MSI-H colorectal cancers are younger age, lower incidence of lymph node metastasis, proximal location, and better survival rate[7,8].

In gastric cancer, the frequency of MSI-H phenotype varies from 8.2% to 37%, depending on the number of cases investigated and the definitions used[9,10]. The distinct features frequently reported for MSI-H gastric cancers include older age, antral location, intestinal type by Lauren classification, expanding type by Ming classification, and better survival[10-13]. However, studies with limited numbers of patients have reported conflicting results regarding the association of the MSI-H phenotype with better survival[14,15].

Since a limited number of previous studies have dealt with endoscopic and pathologic findings of early gastric cancer (EGC) according to MSI phenotype and most were focused on advanced gastric cancer (AGC)[10-13,16], we set out to analyze and clarify endoscopic and pathologic characteristics of EGC according to MSI phenotype in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and tissue samples

From December 2003 to October 2007, 981 patients underwent radical total or subtotal gastrectomy and lymph node dissection for EGC, and the specimens of all patients in this period were examined for MSI status. EGC was defined as gastric cancer limited to mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of lymph node status[17]. Of 981 patients who were pathologically confirmed as having EGC, 73 (7.4%) cases were categorized as MSI high EGC. For comparison, 146 non-MSI high EGC cases from the remaining 908 patients were consecutively selected as controls. Authorization for the use of these tissues for research purposes was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University College of Medicine.

Microsatellite analysis

Areas of tumor and non-tumorous tissues on the slides were examined and marked under light microscopy. DNA was extracted from the uncovered hematoxylin and eosin-stained 6 μm-thick sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

A panel of five National Cancer Institute workshop-recommended microsatellite markers (BAT25, BAT26, D2S123, D17S250 and D5S346) was used for analysis[18]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using a fluorescently labeled multiprimer, HotStar Taq polymerase (Qiagen) and the GeneAmp PCR system 2700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR conditions comprised of an initial cycle of 15 min at 95 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 57 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C. Amplification was completed with a final 5 min at 72 °C. Automated ABI PRISM sequencer model 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) was used to analyze amplified PCR products according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

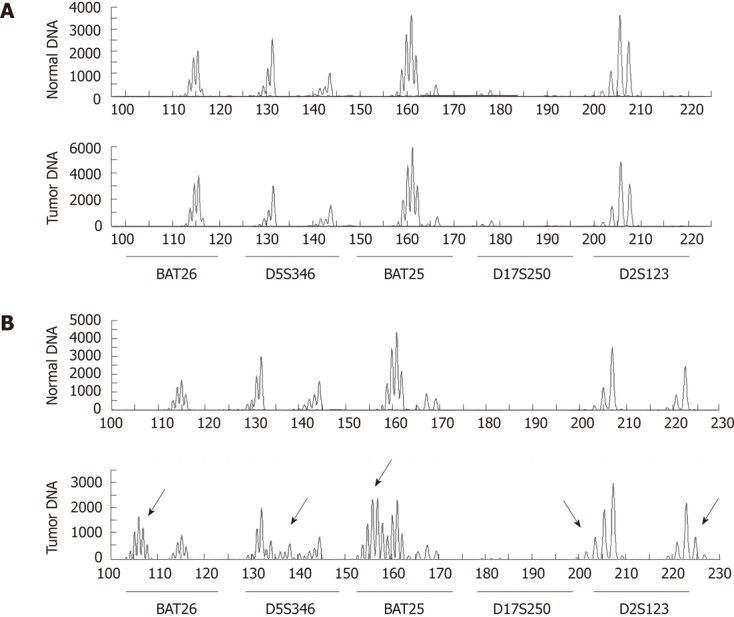

MSI-H was classified as shift of two or more microsatellite markers. Microsatellite instability at only one marker was classified as MSI-low (MSI-L). A case with no microsatellite instability was classified as microsatellite stable (MSS). The PCR results of typical MSS and MSI-H cases are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Polymerase chain reaction results of microsatellite analysis markers. A: Typical case of microsatellite stable early gastric cancer with no frameshift mutation; B: Typical case of high microsatellite instability showing frameshift mutations at 4 markers (BAT26, D5S346, BAT25 and D2S123, indicated as arrow).

Analysis of endoscopic features

Two experienced endoscopists retrospectively reviewed the digital PACS images and the endoscopy database for all 219 cases. Most of the upper endoscopies were performed using GIF-Q260 or GIF-H260 (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan), and a few cases were performed using GIF-Q240 in the early period of 2003. The endoscopic variables included in the analysis were the macroscopic classification of EGC by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, which has been internationally accepted[19,20], location, color pattern and demarcation of the tumor. Additionally, the endoscopic degree of mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in the surrounding mucosa, and the presence of synchronous neoplasm were also included in the analysis. A synchronous lesion was defined as a distinctly separated lesion from the main EGC based on endoscopic findings. The endoscopic variables were compared between the MSI-H and non-MSI-H EGC groups.

Analysis of clinicopathologic features

Clinical information, including age and sex, was obtained from medical records. The pathologic specimens of all 219 cases were reviewed again by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist, and categorized as intestinal, diffuse, or mixed according to the classification of Lauren. The mixed type by Lauren classification was regarded as intestinal type on analysis. The presence of a mucinous component or a signet ring cell component were defined when these components exceeded 10% of the tumor area. Lymphoid stromal reaction was categorized subjectively as absent, mild, moderate, or severe. Other pathologic variables for analysis included differentiation by World Health Organization (WHO) classification, invasion depth, lymphovascular invasion and co-existing underlying adenoma.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using PASW version 18.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The χ2 test was performed for comparison between the MSI-H and MSS/MSI-L groups in terms of various clinicopathologic parameters. The data for age and tumor size were analyzed by Student’s t-test. Each parameter was also assessed by logistic regression. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Estimated relative risks of MSI-H with endoscopic and clinicopathologic factors of EGC were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

RESULTS

Clinical and endoscopic features of MSI-H EGCs

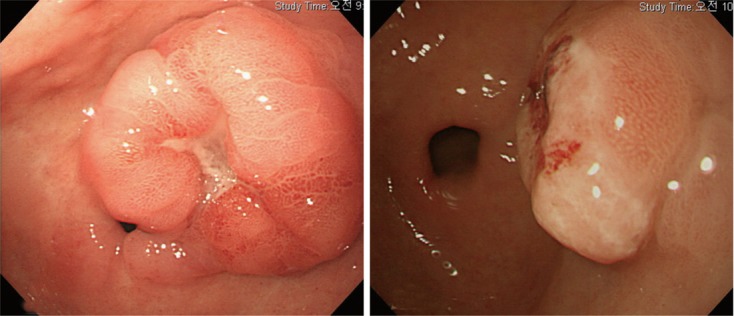

Of 981 EGC cases, 73 cases (7.4%) showed the MSI-H phenotype. The endoscopic features of MSI-H EGCs are summarized in Table 1. MSI-H EGCs presented more frequently with elevated gross type (60.3% of type I or IIa; P < 0.001), antral location (P < 0.001), moderate-to-severe atrophy in the surrounding mucosa (P = 0.032), and presence of a synchronous lesion (P = 0.018) than non-MSI-H EGCs. The typical endoscopic findings of MSI-H EGC are illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of endoscopic features between the high microsatellite instability and non-high microsatellite instability early gastric cancer groups n (%)

| Endoscopic findings | MSI-H EGC (n = 73) | Non-MSI-H EGC(n = 146) | P value |

| Main gross type | < 0.001 | ||

| Type I | 21 (28.8) | 16 (11.0) | |

| Type IIa | 23 (31.5) | 22 (15.1) | |

| Type IIb | 13 (17.8) | 48 (32.9) | |

| Type IIc | 9 (12.3) | 51 (34.9) | |

| Type III | 7 (9.6) | 9 (6.2) | |

| Location | < 0.001 | ||

| Antrum | 56 (76.7) | 66 (45.2) | |

| Body | 15 (20.5) | 77 (52.7) | |

| Cardia | 2 (2.7) | 3 (2.1) | |

| Color | 0.117 | ||

| Whitish color | 2 (2.7) | 9 (6.2) | |

| Normal mucosal color | 27 (37.0) | 36 (24.7) | |

| Erythematous color | 44 (60.3) | 101 (69.2) | |

| Demarcation | 0.265 | ||

| Definite | 45 (61.6) | 101 (69.2) | |

| Obscure | 28 (38.4) | 45 (30.8) | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.138 | ||

| Absent-to-mild | 41 (56.2) | 97 (66.4) | |

| Moderate-to-severe | 32 (43.8) | 49 (33.6) | |

| Mucosal atrophy | 0.032 | ||

| Absent-to-mild | 22 (30.1) | 66 (45.2) | |

| Moderate-to-severe | 51 (69.9) | 80 (54.8) | |

| Synchronous lesion | 14 (19.2) | 12 (8.2) | 0.018 |

MSI-H: High microsatellite instability; EGC: Early gastric cancer.

Figure 2.

Typical endoscopic findings of microsatellite instability mutation early gastric cancer. Typical endoscopic features of high microsatellite instability early gastric cancers, which are grossly protruded type, arising from co-existing underlying adenoma, at an antral location.

The color pattern and demarcation of the tumor, and the degree of intestinal metaplasia in the surrounding mucosa, were not significantly different between the MSI-H EGC and non-MSI-H EGC groups.

Clinicopathologic features of MSI-H EGCs

The clinicopathologic features of MSI-H EGCs are summarized in Table 2. In comparison to non-MSI-H EGCs, MSI-H EGCs were characterized by more frequent female sex (P = 0.001), older age (P < 0.001), better differentiation by WHO classification (P = 0.003), intestinal type by Lauren classification (P = 0.017), presence of a mucinous component (P = 0.017), absence of a signet ring cell component (P = 0.041), moderate-to-severe lymphoid stromal reaction (P = 0.002) and co-existing underlying adenoma (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference between the MSI-H EGC and non-MSI-H EGC groups in terms of tumor size, depth of invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and lymph node metastasis. The endoscopically identified synchronous lesions of the MSI-H EGCs were diagnosed pathologically as EGC in 9.6% and adenoma in 9.6%. Synchronous lesions (P = 0.018) were significantly more frequent in the MSI-H EGC group when cases of EGC and adenoma were combined. However, this difference lost its significance when synchronous EGC (P = 0.110) or adenoma (P = 0.163) were compared separately.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinicopathologic findings between the high microsatellite instability and non-high microsatellite instability early gastric cancer groups n (%)

| MSI-HEGC(n = 73) | Non-MSI-H EGC (n = 146) | P value | |

| Patients characteristics | |||

| Sex | 0.001 | ||

| Male | 37 (50.7) | 108 (74.0) | |

| Female | 36 (49.3) | 38 (26.0) | |

| Age (yr) | 63.4 ± 10.4 | 56.8 ± 11.1 | < 0.001 |

| Pathologic findings | |||

| Size (mm) | 22.4 ± 15.7 | 26.5 ± 13.0 | 0.055 |

| Depth of invasion | |||

| Mucosa | 27 (37.0) | 71 (48.6) | 0.102 |

| Submucosa | 46 (63.0) | 75 (51.4) | |

| Histologic differentiation | 0.003 | ||

| (by WHO classification) | |||

| Well differentiated tubular | 24 (32.9) | 32 (21.9) | |

| Moderately differentiated tubular | 30 (41.1) | 48 (32.9) | |

| Poorly differentiated tubular | 6 (8.2) | 29 (19.9) | |

| Signet ring cell | 8 (11.0) | 43 (24.0) | |

| Mucinous | 5 (6.8) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Lauren classification | 0.017 | ||

| Intestinal | 61 (83.6) | 100 (68.5) | |

| Diffuse | 12 (16.4) | 46 (31.5) | |

| Mucinous component | 7 (9.6) | 3 (2.1) | 0.017 |

| No signet ring cell component | 60 (90.4) | 116 (79.5) | 0.041 |

| Co-existing underlying adenoma | 29 (39.7) | 29 (19.9) | 0.002 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 17 (23.3) | 22 (15.1) | 0.134 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 12 (16.4) | 14 (9.6) | 0.14 |

| Lymphoid stromal reaction | 0.002 | ||

| Absent-to-mild | 49 (74.2) | 91 (91.9) | |

| Moderate-to-severe | 17 (25.8) | 8 (8.1) | |

| Synchronous lesion | 0.018 | ||

| Early gastric cancer | 7 (9.6) | 5 (4.8) | 0.11 |

| Adenoma | 7 (9.6) | 7 (3.4) | 0.163 |

MSI-H: High microsatellite instability; EGC: Early gastric cancer; WHO: World Health Organization.

Correlation between MSI-H and endoscopic and clinicopathologic features of EGCs

We analyzed the interrelationship between MSI-H phenotype and other endoscopic and clinicopathologic factors of EGC by logistic regression analysis (Table 3). Upon logistic regression analysis, MSI-H EGC was significantly associated with elevated gross type (OR 4.38, 95% CI: 2.40-8.01, P < 0.001), antral location (OR 3.99, 95% CI: 2.12-7.52, P < 0.001), moderate-to-severe atrophy of the surrounding mucosa (OR 1.91, 95% CI: 1.05-3.47, P = 0.033), female sex (OR 2.77, 95% CI: 1.53-4.99, P < 0.001), older age (> 70 years) (OR 3.30, 95% CI: 1.57-6.92, P = 0.002), a synchronous lesion (OR 2.65, 95% CI: 1.16-6.07, P = 0.021), better histologic differentiation (OR 2.35, 95% CI: 1.27-4.34, P = 0.007), intestinal type by Lauren classification (OR 2.34, 95% CI: 1.15-4.76, P = 0.019), less signet ring cell component (OR 2.44, 95% CI: 1.02-5.86, P = 0.046), presence of a mucinous component (OR 5.06, 95% CI: 1.27-20.17, P = 0.022), moderate-to-severe lymphoid stromal reaction (OR 3.95, 95% CI: 1.59-9.80, P = 0.003), and co-existing underlying adenoma (OR 2.66, 95% CI: 1.43-4.95, P = 0.002).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of endoscopic and clinicopathologic features of high microsatellite instability early gastric cancer

| OR |

95% CI |

P value | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Endoscopic factors | ||||

| Elevated gross type (I or IIa) | 4.38 | 2.40 | 8.01 | < 0.001 |

| Antral location | 3.99 | 2.12 | 7.52 | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal metaplasia (moderate-to-severe) | 1.55 | 0.87 | 2.75 | 0.139 |

| Mucosal atrophy (moderate-to-severe) | 1.91 | 1.05 | 3.47 | 0.033 |

| Clinicopathologic factors | ||||

| Female sex | 2.77 | 1.53 | 4.99 | < 0.001 |

| Age ≥ 70 years | 3.30 | 1.57 | 6.92 | 0.002 |

| Histologic differentiation (well or moderately) | 2.35 | 1.27 | 4.34 | 0.007 |

| Lauren classification (intestinal type) | 2.34 | 1.15 | 4.76 | 0.019 |

| Submucosal invasion | 1.61 | 0.91 | 2.87 | 0.103 |

| Less signet ring cell component | 2.44 | 1.02 | 5.86 | 0.046 |

| Mucinous component | 5.06 | 1.27 | 20.17 | 0.022 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 1.86 | 0.81 | 4.25 | 0.144 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 1.71 | 0.84 | 3.47 | 0.137 |

| Lymphoid stromal reaction (moderate-to-severe) | 3.95 | 1.59 | 9.80 | 0.003 |

| Co-existing underlying adenoma | 2.66 | 1.43 | 4.95 | 0.002 |

| Synchronous EGC or adenoma | 2.65 | 1.16 | 6.07 | 0.021 |

OR: Odds ratios; CI: Confidence intervals; EGC: Early gastric cancer.

DISCUSSION

Although the worldwide incidence of gastric cancer has been declining steadily, it remains the fourth most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide[21]. Despite identification of numerous genetic alterations in gastric cancers, their roles in tumorigenesis remain unclear. Across the gastrointestinal tract, the role of MSI-H tumor has been studied more often in colorectal cancer than in gastric cancer, and MSI is one of the clinically significant prognostic factors that is recommended for collection in the 2010 tumor, node, metastasis staging criteria for colorectal cancer[22,23]. On the other hand, there is no definite consensus about the role of MSI-H in gastric cancer, and up to now, the majority of MSI-H gastric cancer studies have focused on AGC and its prognosis. However, the clinicopathologic features and therapeutic approaches, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection, for EGCs are different from those for AGCs. In the present study, we focused on endoscopic and clinicopathologic features of MSI-H phenotype in EGCs.

Our results revealed that EGC with MSI-H exhibits distinct clinicopathologic features, including distribution of older age and female sex, antral tumor location, elevated gross morphology, better histologic differentiation, intestinal type by Lauren classification, absence of a signet cell component, presence of a mucinous component, moderate-to-severe lymphoid stromal reaction, co-existing underlying adenoma, and more synchronous lesions including EGC and adenoma. Among the endoscopic features, the correlation between MSI-H and elevated gross morphology was a significant novel finding.

It is reasonable to suspect that elevated gross type of MSI-H EGCs could be explained by cancer progression from co-existing underlying adenoma. And if we take into account the adenoma-carcinoma sequence in carcinogenesis of gastrointestinal tract cancers, our data indicate that MSI-H EGC could more frequently originate from the co-existing underlying adenoma than non-MSI-H EGC. As a consequence, EGC characterized by elevated mass might be preceded by transformation of co-existing underlying adenoma.

A high MSI level has been shown to play an important role in the development of multiple carcinomas in colorectal cancer[24,25]. Several previous studies, which did not distinguish between AGC and EGC, have also shown that multiple synchronous gastric cancer is frequently associated with MSI-H[26,27]. In the present study, MSI-H EGCs were more often associated with synchronous epithelial neoplasm including EGC and adenoma than non-MSI-H, although the difference was not significant when the definition of synchronous lesion was limited to carcinoma, but this may be due to small sample size in each group. Nevertheless, our data indicate that clinicians must consider the potential for synchronous lesions including adenomas and carcinomas in cases of EGC with a confirmed MSI-H phenotype.

In our analysis, MSI-H EGCs were more frequently associated with co-existing underlying adenoma than non-MSI-H EGCs, and had a tendency to have synchronous adenoma. Given this association between MSI-H phenotype and adenoma, we cautiously propose that MSI impacts tumorigenesis at an earlier phase than dysplasia. This hypothesis is supported by results from previous studies revealing that MSI might play an important role in the early events of progression from metaplasia or dysplasia to precancerous lesions, and then to gastric cancer[28,29]. Although there are a limited number of studies on the significance of the main 5 MSI mutations in EGC, a retrospective study from a high risk area of gastric cancer in Italy showed that MSI is part of the spectrum of genetic alterations in gastric non-invasive neoplasia[30].

Our study was limited by the fact that we only included cases of EGC treated with surgery, which may serve as a bias. We excluded patients with EGCs who underwent endoscopic resection due to uncertainty of lymph node metastasis. Therefore, careful interpretation of our results is needed to avoid bias and additional data from other studies that include all EGCs are required to validate our findings. Also, since this is a retrospective study and there are no actual data to support the temporal relationship between adenoma and progression into EGC, speculation that EGC originated from underlying adenoma may be overstretching. We used the term “co-existing underlying adenoma” instead of “origin in underlying adenoma” to cope with this limitation.

In conclusion, this study found that MSI-H EGCs more frequently present as protruded (type I or IIa) type in comparison to non-MSI-H EGCs, which is a novel finding; this is likely related to frequent co-existing underlying gastric adenoma. MSI-H EGC was found to have specific clinicopathologic characteristics, including older age, female dominance, antral location, moderate-to-severe atrophy of the surrounding mucosa, better histologic differentiation, intestinal type by Lauren classification, presence of mucinous component, absence of a signet ring cell component, moderate-to-severe lymphoid stromal reaction, underlying adenoma, and synchronous lesions. The finding of more frequent synchronous lesions in MSI-H EGC warrants us to inspect the stomach more thoroughly for other synchronous adenoma or EGC. Altogether, these findings could be used to better serve our understanding of tumorigenesis and progression in MSI-H EGC, and could be used to set up diagnostic and treatment strategies in EGC patients.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric carcinoma is the fourth most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide. Various genetic alterations have been found in gastric cancers, although their roles in tumorigenesis remain unclear. Detection in the early stage and prevention of progress to advanced cancer are crucial in lowering gastric carcinoma related morbidity and mortality.

Research frontiers

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is a hallmark of a deficiency in the DNA mismatch repair system and is one of the pathways leading to gastric carcinogenesis. However, there are limited data on endoscopic and clinicopathologic characteristics of early gastric cancer (EGC) according to MSI phenotypes.

Innovations and breakthroughs

EGCs with high MSI frequently presented with elevated or protruded pattern, which is a novel finding. In addition, EGCs with high MSI showed more frequent synchronous lesions. Other significant endoscopic and clinicopathologic findings of high MSI (MSI-H) EGCs included moderate-to-severe atrophy in the surrounding mucosa, antral location, predominance of female sex, older age, better histologic differentiation, intestinal type by Lauren classification, absence of a signet ring cell component, presence of mucinous component, moderate-to-severe lymphoid stromal reaction, and co-existing underlying adenoma.

Applications

EGCs with MSI-H seem to originate from underlying adenoma, following an adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Furthermore, more synchronous lesions in MSI-H EGCs indicate that thorough inspection and shorter follow up period is needed for endoscopic surveillance after diagnosis of early gastric carcinoma with MSI-H.

Peer review

This study evaluates relationship of phenotypic characteristics (endoscopic and clinicopathologic) of EGC with MSI-H. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that MSI-H EGCs more frequently presented with elevated pattern (type I or IIa), moderate-to-severe atrophy in the surrounding mucosa, antral location and synchronous lesions than non-MSI-H EGCs.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Limas Kupcinskas, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Kaunas University of Medicine, Mickeviciaus 9, LT, 44307 Kaunas, Lithuania; Liang-Shun Wang, MD, Professor, Vice-superintendent, Shuang-Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, No. 291, Jhongjheng Rd., Jhonghe City, New Taipei City 237, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Brentnall TA. Microsatellite instability. Shifting concepts in tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:561–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duval A, Hamelin R. Genetic instability in human mismatch repair deficient cancers. Ann Genet. 1995;45:71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3995(02)01115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard SM, Bailliet G, Páez GL, Bianchi MS, Peltomäki P, Bianchi NO. Nuclear and mitochondrial genome instability in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4231–4237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianchi NO, Bianchi MS, Richard SM. Mitochondrial genome instability in human cancers. Mutat Res. 2001;488:9–23. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Liu VW, Ngan HY, Nagley P. Frequent occurrence of mitochondrial microsatellite instability in the D-loop region of human cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1042:123–129. doi: 10.1196/annals.1338.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata D, Peinado MA, Ionov Y, Malkhosyan S, Perucho M. Genomic instability in repeated sequences is an early somatic event in colorectal tumorigenesis that persists after transformation. Nat Genet. 1994;6:273–281. doi: 10.1038/ng0394-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, Aronson MD, Holowaty EJ, Bull SB, Redston M, Gallinger S. Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:69–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang JT, Huang KC, Cheng AL, Jeng YM, Wu MS, Wang SM. Clinicopathological and molecular biological features of colorectal cancer in patients less than 40 years of age. Br J Surg. 2003;90:205–214. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu M, Semba S, Oue N, Ikehara N, Yasui W, Yokozaki H. BRAF/K-ras mutation, microsatellite instability, and promoter hypermethylation of hMLH1/MGMT in human gastric carcinomas. Gastric Cancer. 2004;7:246–253. doi: 10.1007/s10120-004-0300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo HM, Chang YS, Joo SH, Kim YW, Park YK, Hong SW, Lee SH. Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of gastric cancers with the MSI-H phenotype. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:143–147. doi: 10.1002/jso.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HS, Choi SI, Lee HK, Kim HS, Yang HK, Kang GH, Kim YI, Lee BL, Kim WH. Distinct clinical features and outcomes of gastric cancers with microsatellite instability. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:632–640. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falchetti M, Saieva C, Lupi R, Masala G, Rizzolo P, Zanna I, Ceccarelli K, Sera F, Mariani-Costantini R, Nesi G, et al. Gastric cancer with high-level microsatellite instability: target gene mutations, clinicopathologic features, and long-term survival. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:925–932. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corso G, Pedrazzani C, Marrelli D, Pascale V, Pinto E, Roviello F. Correlation of microsatellite instability at multiple loci with long-term survival in advanced gastric carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2009;144:722–727. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beghelli S, de Manzoni G, Barbi S, Tomezzoli A, Roviello F, Di Gregorio C, Vindigni C, Bortesi L, Parisi A, Saragoni L, et al. Microsatellite instability in gastric cancer is associated with better prognosis in only stage II cancers. Surgery. 2006;139:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.dos Santos NR, Seruca R, Constância M, Seixas M, Sobrinho-Simões M. Microsatellite instability at multiple loci in gastric carcinoma: clinicopathologic implications and prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:38–44. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KM, Kim YS, Cho JY, Jung IS, Kim WJ, Choi IS, Ryu CB, Kim JO, Lee JS, Jin SY, et al. [Significance of microsatellite instability in early gastric cancer treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;51:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, Sidransky D, Eshleman JR, Burt RW, Meltzer SJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Fodde R, Ranzani GN, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endoscopic Classification Review Group. Update on the paris classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the digestive tract. Endoscopy. 2005;37:570–578. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thibodeau SN, French AJ, Roche PC, Cunningham JM, Tester DJ, Lindor NM, Moslein G, Baker SM, Liskay RM, Burgart LJ, et al. Altered expression of hMSH2 and hMLH1 in tumors with microsatellite instability and genetic alterations in mismatch repair genes. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4836–4840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamashita K, Arimura Y, Kurokawa S, Itoh F, Endo T, Hirata K, Imamura A, Kondo M, Sato T, Imai K. Microsatellite instability in patients with multiple primary cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2000;46:790–794. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.6.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohtani H, Yashiro M, Onoda N, Nishioka N, Kato Y, Yamamoto S, Fukushima S, Hirakawa-Ys Chung K. Synchronous multiple primary gastrointestinal cancer exhibits frequent microsatellite instability. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:678–683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000601)86:5<678::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyoshi E, Haruma K, Hiyama T, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Shimamoto F, Chayama K. Microsatellite instability is a genetic marker for the development of multiple gastric cancers. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:350–353. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20011120)95:6<350::aid-ijc1061>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinmura K, Sugimura H, Naito Y, Shields PG, Kino I. Frequent co-occurrence of mutator phenotype in synchronous, independent multiple cancers of the stomach. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2989–2993. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.12.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeong CW, Lee JH, Sohn SS, Ryu SW, Kim DK. Mitochondrial microsatellite instability in gastric cancer and gastric epithelial dysplasia as a precancerous lesion. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaky AH, Watari J, Tanabe H, Sato R, Moriichi K, Tanaka A, Maemoto A, Fujiya M, Ashida T, Kohgo Y. Clinicopathologic implications of genetic instability in intestinal-type gastric cancer and intestinal metaplasia as a precancerous lesion: proof of field cancerization in the stomach. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:613–621. doi: 10.1309/DFLELPGPNV5LK6B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rugge M, Bersani G, Bertorelle R, Pennelli G, Russo VM, Farinati F, Bartolini D, Cassaro M, Alvisi V. Microsatellite instability and gastric non-invasive neoplasia in a high risk population in Cesena, Italy. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:805–810. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.025676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]