INTRODUCTION

Primary tumors of the heart are rare, with an incidence between 0.0017% and 0.19% in unselected patients at autopsy. Approximately 75% of the tumors are benign, and nearly half of them are myxomas (1) Atrial myxoma is the most common benign cardiac neoplasm, and its origin has been ascribed to a multipotential mesenchymal cell (2) Myxomas commonly occur between the third and sixth decades of life and are three times more frequent in women (3) There are two distinctive forms of the tumors: solid and ovoid myxomas and soft and papillary myxomas. Solid tumors are more likely to present with symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF), while papillary tumors are more likely to embolize to the cerebral and other peripheral vessels (4) At the time of diagnosis, 92% of the patients have symptoms of CHF (5) Atrial myxoma may mimic valvular heart disease, cardiac insufficiency, cardiomegaly, bacterial endocarditis, disturbances of ventricular and supraventricular rhythm, syncope, and systemic or pulmonary embolism (3) The purpose of this paper is to present a case report of atrial myxoma mimicking severe mitral valve stenosis at cardiac auscultation and the importance of echocardiograpy in the diagnosis.

CASE DESCRIPTION

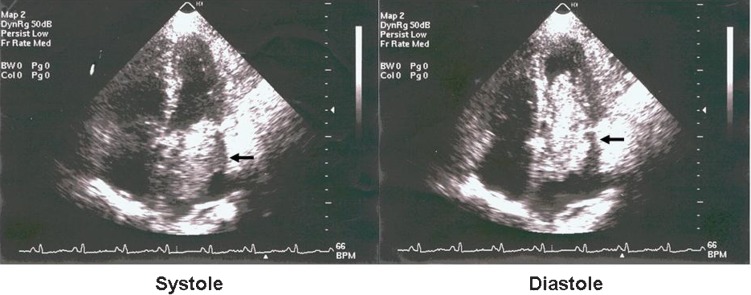

A 77-year-old Caucasian man presented at the Emergency Care Unit with a six-month history of congestive heart failure and in funcional class III, according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) criteria. He had no previous history of diabetes, arterial hypertension, or ischemic coronary disease. The physical examination disclosed distended neck veins, rales at the lung base, and hepatomegaly. Cardiac auscultation revealed a loud first heart sound and diastolic rumble resembling mitral valve stenosis. Chest radiography showed a normal cardiac silhouette image, enlarged hilar shadows and moderate right-sided pleural effusion. The electrocardiogram showed a regular sinus rhythm with a nonspecific repolarization alteration. The transthoracic echocardiogram showed an image of a large pediculate mass of 5.5 mm×4.0 mm in the left atrium in his greater diameters, restricting transmitral diastolic blood flow, and an atrium-ventricular pressure gradient of 11 mmHg (Figure 1). This mass was attached to the inferior edge of the fossa ovalis. Left ventricular function was normal, and the right ventricular diameter was 3.2 cm. His systolic pulmonary artery pressure was 100 mmHg. The patient was referred for cardiac surgery. The adopted technique was a biatrial approach. The intraoperative findings included a mass, and anatomopathologic analysis confirmed that it was an atrial myxoma. Two days after surgery, an echodopplercardiogram showed an important reduction in systolic pulmonary artery pressure to 30 mmHg. Five years later, an echocardiogram showed no mass in the left atrial chamber.

Figure 1.

Giant obstructive left atrial mixoma (arrows) in systole and diastole.

DISCUSSION

This case report showed an atrial myxoma mimicking mitral valve stenosis. The diagnosis was made by echocardiogram, which disclosed a huge mass obstructing the left atrial blood flow. Heart valve disease is one of the differential diagnoses of atrial myxomas. The clinical findings of cardiac tumors are characterized by the triad of embolism, intracardiac obstruction, and constitutional findings. Congestive heart failure is the most common clinical presentation, followed by neurologic and systemic embolic events. Embolic events more frequently affect the cerebral arteries, including the retinal arteries. Embolization into visceral, renal, or coronary arteries has also been reported and can affect nearly 29% of patients (3). Although the large majority of myxomatous emboli are cerebral, it is possible for atrial myxomas to embolize and implant in other locations in the visceral and peripheral arterial circulation. Ectopic myxoma implants have been described in other unusual locations, including the skin, the skeleton, and the small bowel. Intracardiac obstruction with impaired filling of the left or right ventricle causes subsequent dyspnea, recurrent pulmonary edema, right-heart failure or even syncope or sudden death (6). Three fourths of myxomas are located in the left atrium (7). General or constitutional manifestations, such as fatigue, fever, weight loss, night sweats, arthralgia, and laboratory abnormalities, such as elevation of C-reactive protein, anemia, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, can also occur.

Mitral valve obstruction caused by atrial myxoma represents an important hemodynamic consequence leading to symptoms of congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, syncope, and sudden death. Clinicopathologic correlations showed that mitral stenotic effects occurred when the tumor diameter exceeded 5 cm (8). Echodopplercardiography is the most important method for the differential diagnosis with primary valve disease. Moreover, it can estimate the transvalve gradient. It has been reported that patients with left atrial myxomas have reduced transmitral blood flow. Nevertheless, only large myxomas can resemble severe mitral stenosis. The differential diagnosis of an intracardiac mass encompasses benign and malignant primary heart tumors, metastatic tumors and thrombi. Eletrocardiographic findings are unspecific. The cardiac rhythm is usually normal. Chest X-ray may reveal an enlargement of the left atrium and some signs of pulmonary hypertension and congestion. Calcifications, which make the tumor visible on routine radiographic examination, are unusual. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can differentiate tissue composition, making it possible to identify the nature of the mass. The preoperative diagnosis of cardiac tumors could be performed correctly utilizing angiography, echocardiography, or both. Coronary angiography is reserved for older patients who may have coexisting coronary artery disease (9).

Controversy remains regarding the optimal operative approach to atrial myxomas. The biatrial approach has been advocated to achieve the most complete tumor excision and assess the possibility of tumors in the right atrium (10). Other options include minimally invasive thoracoscopic surgery and the use of robotic technology. Surgical excision of the tumor appears to be curative, and recurrence is rare, as shown five years later in an echocardiogram of this patient.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silverman NA. Primary cardiac tumors. Ann Surg. 1980;191(2):127–138. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198002000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansson L. Histogenesis of cardiac myxomas. An immunohistochemical study of 19 cases including one with glandular structures and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989;113(7):735–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Eng J Med. 1995;333(24):1610–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimono T, Makino S, Kanamori Y, Kinoshita T, Yada I. Left atrial myxomas: Using gross anatomic tumor types to determine clinical features and coronary angiographic findings. Chest. 1995;107(3):674–679. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.3.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swartz MF, Lutz CJ, Chandan VS, Landas S, Fink GW. Atrial Myxomas: Pathologic Types, Tumor Location, and Presenting Symptoms. J Card Surg. 2006;21(4):435–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2006.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung R, Ghahramani A, Mallon S, Richter S, Sommer L, Gottlieb S, Myerburg R. Hemodynamic features of prolapsing and nonprolapsing left atrial myxoma. Circulation. 1975;51(5):342–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.51.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaff HV, Mullany CJ. Surgery for cardiac myxomas. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(2):77–88. doi: 10.1053/ct.2000.5079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pucci A, Gagliardotto P, Zanini C, Pansini S, di Summa M, Mollo F. Histopathologic and clinical characterization of cardiac myxoma: review of 53 cases from a single institution. Am Heart J. 2000;140(1):134–8. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.107176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson S, Lepore V, Kennergren C. Atrial myxomas: Results of 25 years' experience and review of the literature. Surgery. 1989;105(6):695–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones DR, Warden HE, Murray GF, Hill RC, Graeber GM, Cruzzavala JL, et al. Biatrial approach to cardiac myxomas: A 30-year clinical experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59(4):851–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00064-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]