Abstract

Introduction

The continued growth in the number of elderly with cancer and age-related chronic diseases will cause in Poland an increase in demand for palliative care. The aim of the study was to identify chronic comorbidities and cancer types in palliative home care patients and to compare their incidence with the general Polish population.

Material and methods

The data was obtained from 543 patients who received palliative home care between 2005-2009. The occurrence of the most common chronic conditions such as arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, chronic pulmonary diseases and central nervous system diseases were analysed together with the cancer types.

Results

The study group included 259 women (47.7%) and 284 men (52.3%) aged 25-91 years old. The most common primary neoplasm locations for men were lung (28.2% vs. 21.4% in general population) and colorectal cancer (18.7% vs. 11.4% in general population), and in women breast (19.7% vs. 22.8% in general population) and colorectal cancer (17.4% vs. 9.2% in general population). The incidence of ischemic heart disease, diabetes, and chronic pulmonary diseases was significantly different in comparison to the general populations (47.0% vs. 11.3%; 20.3% vs. 6.8%; 16.6% vs. 27.5%, respectively). The mean number of concomitant diseases was 1.6 for women and 1.8 for men vs. 1.7 and 1.2 in the general Polish population respectively.

Conclusions

The majority of the patients had concomitant disease, with cardiovascular diseases being most common. The most common primary neoplasm diagnoses in palliative home care patients were lung and colorectal cancer, which corresponds to the cancer prevalence in the general population.

Keywords: advanced cancer, palliative care, comorbidities, elderly

Introduction

Cancer with common chronic conditions is the major cause of illness, disability, and death around the world. Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems – physical, psychosocial and spiritual (WHO definition 2002). This task cannot be managed by one single profession but required a multidisciplinary team consisting of a physician, nurse, psychologist, social worker, physiotherapist and others. The system of palliative care should be based on clearly defined strategies, implementing dedicated programs in a friendly environment of the national health system and with the support of non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Poland has one of the best developed palliative care systems in Eastern Europe. Development of palliative care in Poland began in the 1970s, and was closely tied to the Catholic Church and displaced intellectuals [1]. In the 1990s following the political transformation and modernization of the Polish National Health Care system, palliative care began to integrate with public health systems. Analyses of the report prepared for the European Parliament Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety revealed that Poland was ranked fifth in palliative care development in the EU [2, 3]. Despite lower gross domestic product, Polish palliative care was next to such countries as the UK, Sweden, Ireland and the Netherlands. With the well-known demographic changes which are taking place in Poland (Table I) and increased importance in providing care for the ageing population with cancer, there is observed an increase in the palliative care network development. Since 2006, the number of palliative care units in Poland which signed contracts with the National Health Fund (NHF) has increased from 352 to 415 in 2011. Financial outlays issued by the NHF significantly increased from PLN 167.8 million in 2006 to PLN 291 million in 2011 [4]. Only 27 NGOs provided the palliative care services without a contract with the NHF in 2011.

Table I.

Population of Poland by age

| Year | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population [000] | 35 735 | 38 073 | 38 254 | 38 200 | 37 830 | 36 796 |

| 65 years and more [000] | 3589 | 3887 | 4726 | 5185 | 6954 | 8195 |

| 65 years and more [%] | 10 | 10.2 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 18.4 | 22.3 |

In the Polish palliative care system in 2011 there were 145 inpatient palliative units including day care units which received PLN 143 218 million and 121 palliative care outpatient units with a PLN 126.8 million budget. These designated outpatient units according to the Minister of Health regulation of August 29, 2009, apart from medical consultation may provide palliative home care services. In Poland, there were 321 palliative home care units with a PLN 126.8 million budget in 2011 [4].

The Polish palliative care system has its weaknesses. There are still large holes in coverage in many rural areas, especially for the number of inpatient and outpatient palliative care units. On the other hand, particular attention should be paid to the well-developed system of palliative home care services and pediatric palliative services in Poland [4]. It is estimated that 90% of palliative care patients in Poland are those with advanced cancer. The basic form of palliative care is home care provided by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a physician, nurse, psychologist, social worker and physiotherapist. Although patients are eligible for family doctor's and specialists’ consultations, it is a hospice physician that usually provides care by visiting these patients, mainly due to low mobility of the palliative care patient and complex treatment required.

The aim of the study was to identify common cancer types in the studied population admitted to the palliative home care units and compare their incidence to the Polish National Cancer Registry. The second aim of the study was to identify common chronic concomitant diseases in patients with advanced cancer disease and to compare their incidence to the general Polish population.

Material and methods

The study involved 543 patients with advanced cancer disease, consecutively admitted between 2005 and 2009 to the palliative home care unit for longer than 7 days in Lodz Voivodeship. In the study group the occurrence of the following comorbidities was analysed: arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, chronic pulmonary diseases and central nervous system diseases. The incidence of the comorbidities was analysed and compared to the data of the Central Statistical Office in Poland in 2009 [5]. The Central Statistical Office carried out an Environmental Health Information Service (EHIS) survey in accordance with Eurostat recommendations regarding the thematic scope and applied research tools. The authors of the report, which included algorithms of sample selection, calculating weights and precision, were employees of the Methodology, Standards and Registers Division, and the software was developed in the Statistical Computing Centre. Moreover, wherever possible we used data available from nationwide epidemiological studies such as the WOBASZ study [6], PMSEAD study [7] and BOLD study [8].

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using CSS Statistica 8.0 software (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK., USA). The standard χ2 test, as a statistical method, was used to estimate the significance of the association between the age of patients and the presence of the above-mentioned comorbidities, separately. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for testing differences in number of concomitant diseases between two compared groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for testing more than two subgroups of ICD-10 diagnoses. Spearman's rank correlation was used to test correlation of patients’ age and the number of concomitant diseases. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

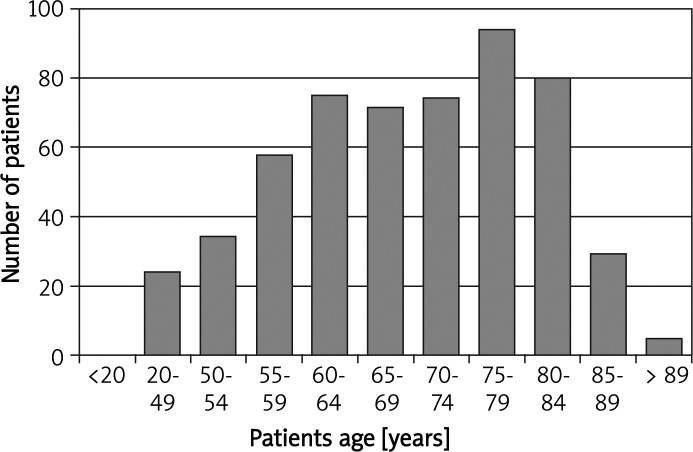

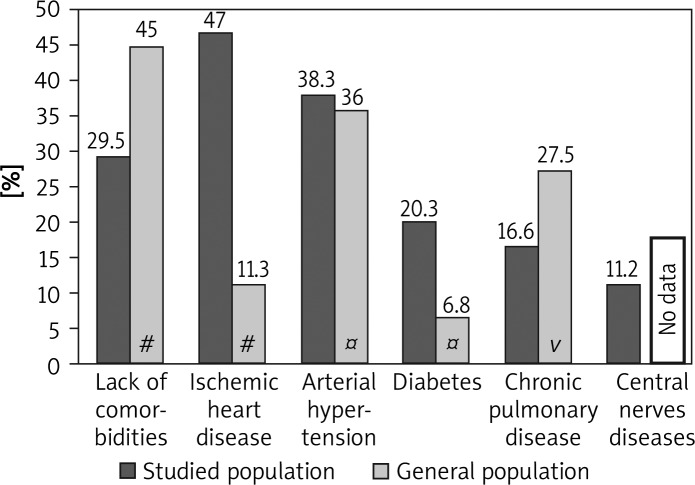

The study group consisted of 259 women (47.7%) and 284 men (52.3%). The patients’ age ranged from 25 to 91 years (median age 69.2 ±11.4 years; Figure 1). The most common primary neoplasm locations in the study group for men were lung (28.2% vs. 21.4% in general population) and colorectal cancer (18.7% vs. 11.4% in general population), and in women breast (19.7% vs. 22.8% in general population) and colorectal cancer (17.4% vs. 9.2% in general population) (Table II). In the study group only 160 patients did not have concomitant disorders (29.5% vs. 45% in general population; Figure 2). However, if the concomitant diseases were present their mean number was 1.6 for women and 1.8 for men vs. 1.7 for women and 1.2 for men in the general Polish population respectively (Table III). Apart from hypertension and central nervous system diseases, the incidence of ischemic heart disease, diabetes, and chronic pulmonary diseases was significantly different in comparison to the general populations (47.0% vs. 11.3%; 20.3% vs. 6.8%; 16.6% vs. 27.5%, respectively; Figure 2). There were no statistically significant differences in occurrence of concomitant diseases between male and female groups (p = 0.2).

Figure 1.

Age structure of study population

Table II.

Oncological diagnoses in studied population and general Polish population in 2009

| Primary neoplasm location | Total | Males | Females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studied population | Studied population | General population | Studied population | General population | |||||

| N | % | N | % | % | N | % | % | ||

| C02-C16 (upper GI tract) | 48 | 8.8 | 30 | 10.6 | 5# | 18 | 6.9 | 2.5# | |

| C18-C20 (colorectal) | 98 | 18.0 | 53 | 18.7 | 11.4 | 45 | 17.4 | 9.2 | |

| C22-C25 (liver, biliary, pancreatic) | 51 | 9.4 | 14 | 4.9 | 2.4® | 37 | 14.3 | * | |

| C34 (lung) | 111 | 20.4 | 80 | 28.2 | 21.4 | 31 | 12.0 | 8.5 | |

| C50 (breast) | 51 | 9.4 | – | – | * | 51 | 19.7 | 22.8 | |

| C53-C56 (female sex organs) | 35 | 6.4 | – | – | – | 35 | 13.5 | 16.8 | |

| C61 (prostate) | 34 | 6.3 | 34 | 12.0 | 13.3 | – | – | – | |

| C64-C67 (urinary) | 40 | 7.4 | 28 | 9.9 | 10.8^ | 12 | 4.6 | 2.7¤ | |

| Other | 75 | 13.8 | 45 | 15.8 | 35.7 | 30 | 11.6 | 37.5 | |

| Total | 543 | 100 | 284 | 100 | 100 | 259 | 100 | 100 | |

Included only stomach cancer

included in the other group

included only pancreatic cancer

included only urinary bladder and kidney cancer

included only kidney cancer

Figure 2.

The incidence of common comorbidities in studied population and general Polish population

#Data available from the Central Statistical Office in Poland in 2009, ¤ data available from the WOBASZ study, vcombined data from the PMSEAD study and BOLD study

Table III.

Prevalence of chronic conditions per person by age group and gender in studied population and general Polish population

| Gender | Age groups [years] | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15-19 | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | 80 | ||

| Females study group* | (n = 0) 0 | (n = 0) 0 | (n = 3) 0 | (n = 12) 0.1 ±0.3 | (n = 43) 0.7 ±1.0 | (n = 62) 1.3 ±1.6 | (n = 76) 2.0 ±1.5 | (n = 62) 2.6 ±1.5 | (n = 259) 1.6 ±1.6 |

| Females general population# | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 1.7 |

| Males study group* | (n = 0) 0 | (n = 1) 1 | (n = 1) 0 | (n = 7) 1.1 ±1.8 | (n = 48) 0.7 ±1.2 | (n = 81) 1.4 ±1.5 | (n = 92) 2.3 ±1.5 | (n = 52) 2.9 ±1.5 | (n = 284) 1.8 ±1.7 |

| Males general population# | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 1.2 |

Not including cancer diseases

data available from the Central Statistical Office in Poland in 2009

The Kruskal-Wallis test in ICD-10 cancer subgroups revealed that there might be some statistical differences in mean numbers of the concomitant diseases depending on the basic diagnosis of cancer (p = 0.012). Detailed analysis revealed a statistical difference in numbers of concomitant diseases in the subgroup of upper gastrointestinal tract cancer vs. other cancer patients (p = 0.028). In this group of patients the mean number of concomitant diseases was less than in all other diagnosed cancer cases (1.27 vs. 1.78). There were also statistically significant differences with a higher mean number of concomitant diseases for prostate cancer patients than in other subgroups (2.41 vs. 1.69; p = 0.007).

The correlation between chronic concomitant diseases and primary cancer location was tested using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient with Bonferroni correction. However, only a weak statistically significant correlation was found between chronic pulmonary diseases and lung cancer (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient 0.20; p < 0.00125).

A positive correlation between patient age and the number of concomitant diseases was found (R = 0.48; p < 0.001). Analysis based on the age decades revealed that there is not statistically significant growth of the mean number of concomitant diseases between the decades 4 to 6, and fast growth in the decade groups 6 to 9 (p < 0.001). This supported the planned separation of younger patients (up to 65 years old; group I) from older ones (over 65 years old; group II) in the further analysis of the occurrence of particular disorders.

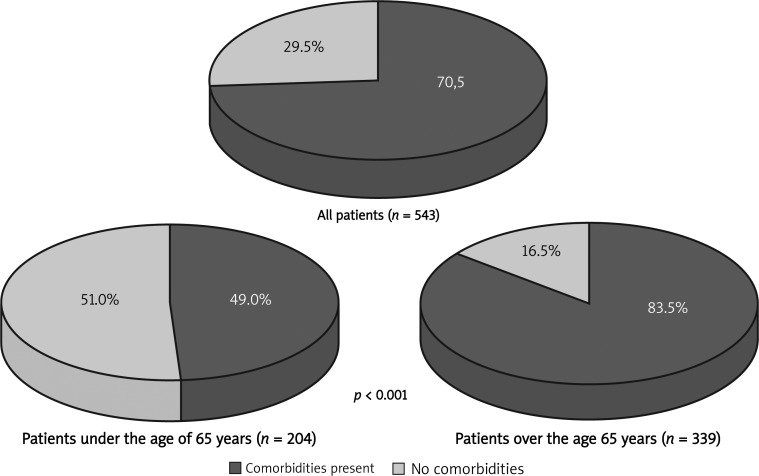

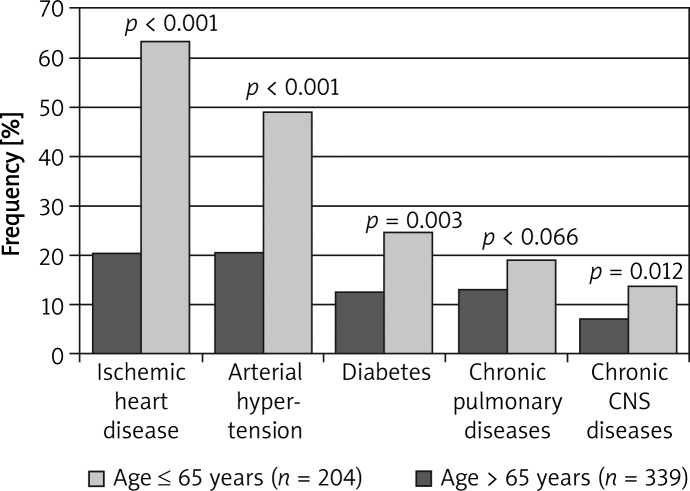

Group I included 204 patients (37.6%) and group II included 339 patients (62.4%) (p < 0.001). The occurrence of concomitant diseases in younger patients was lower than compared to the occurrence in older ones (49.0% vs. 83.5%; p < 0.001; Figure 3). The number of concomitant disorders in younger patients versus older differed significantly (0.91 vs. 2.23; p < 0.001). Lower occurrence of arterial hypertension (p < 0.001), ischemic heart disease (p < 0.001), diabetes (p = 0.003), central nervous system diseases (p = 0.012), and (not significantly) chronic pulmonary diseases (p = 0.066) was observed in younger patients (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Incidence of comorbidities of patients with cancer disease in palliative home care

Figure 4.

Prevalence of common comorbidities due to the age subgroups in the studied population

Discussion

Polish society is an ageing population. In 1980 elderly people (65 years and more) accounted for 10.0% of the total population, whilst in 2010 their proportion grew to 13.6% and in the projection for 2030 it will rise to 22.3%. At the same time the total Polish population will decrease in size (Table I). This will lead to growth of the number of patients with chronic diseases, as they are closely associated with age [9, 10]. Cancer is a growing health and economic problem in Poland. There are around 156 000 new cancer cases per year in Poland and almost 93 000 deaths annually due to neoplasm. The incidence of cancer is 356/105 for men and 332/105 for women. The mortality rate for all cancers was 283/105 for men and 207/105 for women [11]. An exponential age dependence of incidence rates is present in both genders [11, 12].

The studied population differed in terms of gender and age structure in comparison to the general Polish population. There were slightly more men than women admitted to the home care unit but the difference was not statistically significant. This is consistent with other cohort studies and reflects general observations [13]. However, there are more women than men in the general population in Poland and the ratio increases with age. This could mean that men require home care more often than women. The majority (70.5%) of the studied population had at least one concomitant common chronic disease, with ischemic heart disease as the most common. It should be underlined that if there are concomitant diseases in palliative care patients, their mean number is between 2 and 3. As expected, the occurrence of concomitant chronic diseases increases along with the age of patients. However, in the studied population the problem of comorbidity appeared especially in patients of the 7th decade of life and older (Figure 4). That results in an additional burden for palliative care units in terms of additional costs of treatment and should be reflected in the educational curriculum of physicians.

The incidence of ischemic heart disease in our study was 47%, which is four times higher than in the general Polish population (11.3%) [5]. These data are consistent and confirm the fact that cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death (48%) in Poland. Despite the fact that the Polish population is still characterized by a high proportion of subjects with high global risk of fatal cardiovascular disease, especially among men, the death rate from coronary heart disease (from 1991 to 2005) significantly declined [14]. This decline was partially due to the increased efficacy of treatment and major risk factor reduction [15].

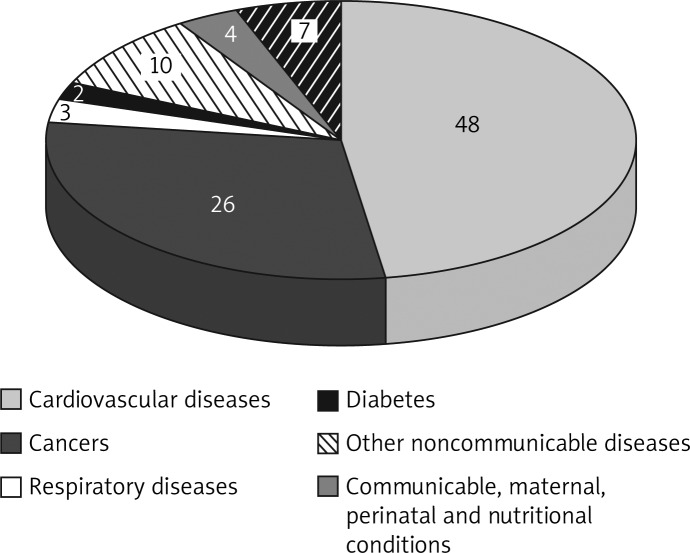

Cancer, respiratory diseases and diabetes are responsible for second, third and fourth place as cause of death, with rates of 26%, 3% and 2%, respectively (Figure 5) [16]. In Poland by 2030 mortality will increase, which will be the result of ageing. Cardiovascular diseases will continue to be the most frequent causes of death but a significant increase of mortality due to diabetes mellitus and prostate cancer as well as malignant neoplasms of the colon, rectum and stomach will be observed [17].

Figure 5.

Proportional mortality (% of total deaths, all ages) in Poland. World Health Organization – NCD Country Profiles, 2011

All chronic diseases, except chronic pulmonary diseases (16.6% vs. 27.5% in the general population), are more frequent in older palliative patients, disregarding the gender of patients (Figure 2). This can be explained by the high rate of lung cancer in the study population (20.4%). Some symptoms which are characteristic for chronic respiratory disease such as dyspnoea and cough may mask the lung cancer, and vice versa. A correlation between chronic concomitant diseases and primary cancer location was only found between chronic pulmonary diseases and lung cancer in our study. According to the combined data from the PMSEAD and BOLD study in Poland, chronic respiratory diseases occur in approximately 27% of people [7, 8]. With the exception of asthma in Poland there are no accurate epidemiological data evaluating the incidence of chronic non-infectious respiratory diseases. However, because 5% of patients with asthma and 20% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have a severe or very severe character, they require hospice care near the end of their life [18]. The Polish Respiratory Society with cooperation of the Polish Palliative Society published recommendations for these purposes in 2011 [19].

In contrast to lung diseases, diabetes was significantly higher in the study population than in the general population (20.3% vs. 6.8%) (Figure 2). Prevalence of diabetes according to gender in the studied population was similar (Table IV). High prevalence of diabetes in the study group was most likely associated with ageing and intensive corticosteroid therapy, which increase glucose intolerance [20]. Corticosteroids are extensively used in advanced cancer for various specific indications such as spinal cord compression, pain relief, hormone therapy and to stimulate appetite and general wellbeing. There are no reliable statistics about the prevalence of diabetes among terminally ill cancer patients. Corticosteroids are prescribed for up to 30% of the palliative home care population [21]. According to some data as many as 37% of non-diabetic patients with advanced cancer would be classified as diabetics after treatment [22]. There is evidence for an association between diabetes (type 2) and cancer, depending on the tumour site. It is the greatest for primary liver cancer, moderately elevated for pancreatic cancer and relatively low for colorectal, endometrial, breast, and renal tumours [23].

Table IV.

Prevalence of diabetes according to age and gender in studied population and in general Polish population (WOBASZ study)

| Gender | Age groups | Total [%] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | ≥ 60 | ||

| Females (n) DM (N = 51)/% | (n = 0) 0 | (n = 3) 0 | (n = 12) 0 | (n = 43) 5/11.6% | (n = 200) 46/23% | 19.7 |

| Females (DM% in general population) | 0.5% | 1.7% | 3.2% | 7.7% | 17.8% | 6.2 |

| Males (n) DM (N = 59)/% | (n = 1) 0 | (n = 1) 0 | (n = 7) 3/42.9% | (n = 48) 3/6.3% | (n = 225) 53/23.6% | 20.9 |

| Males (DM% in general population) | 0.7% | 1.3% | 4.9% | 11.9% | 16.3% | 7.4 |

There are no significant differences in the incidence of hypertension for the study group and the general population (38.3% vs. 36%). Prevalence of hypertension in males was lower in the study group than in the general population (20.9% vs. 35.8%) but higher in females in the study group than in the general population (40.7% vs. 33%) (Table V). In a large study of nearly 300,000 patients, it was found that hypertension is associated with an increased risk of cancer death. Furthermore, hypertension increases risk of developing cancer, although this effect was statistically significant only in men. The link between hypertension and renal cell cancer was found earlier in a metaanalysis of more than 47,000 patients [24–28]. On the other hand, some hypertension drugs may raise cancer risks, but this theory requires more evidence. Moreover, hypertension, and other common chronic diseases can result from unhealthy lifestyles, which can lead to cancer as well. Further studies are necessary.

Table V.

Prevalence of hypertension according to age and gender in studied population and in general Polish population (WOBASZ study)

| Gender | Age groups | Total [%] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | ≥ 75 | ||

| Females (study group) [%] | (n = 2) 0 | (n = 4) 0 | (n = 24) 12.5 | (n = 57) 24.6 | (n = 72) 45.8 | (n = 99) 55.6 | 40.7 |

| Females (% in general population) | 2% | 9% | 27% | 50% | 58% | – | 33 |

| Males (study group) [%] | (n = 1) 0 | (n = 3) 0 | (n = 24) 0 | (n = 72) 42.9 | (n = 91) 6.3 | (n = 91) 51.6 | 20.9 |

| Males (% in general population) | 15% | 25% | 40% | 50% | 56% | – | 35.8 |

We did not analyse patients in our study with different types of central nervous system diseases mainly due to lack of complete data and prevalence of neurological disorders in the general Polish population.

Interestingly, it seemed that the primary neoplasm diagnosis could have some impact on the number of concomitant diseases. The number of concomitant diseases was significantly lower in the subgroup with upper gastrointestinal tract cancers. In contrast, a statistically significant difference with a higher mean number of concomitant diseases was observed in the subgroup with prostate cancer. However, these patients were statistically older than others (mean 77.6 vs. 68.6 years; p = 0.014). No statistical difference was found in other subgroups depending on the primary location of cancer. On the other hand, patients after chemotherapy had almost twice as few concomitant diseases than the rest of the studied group (1.08 vs. 1.96; p < 0.001). However, the reason may be that healthier patients with fewer risk factors were qualified for chemotherapeutic treatment.

In conclusion, the majority of home care palliative patients have concomitant chronic disorders, which imposes an additional burden for the health care units and should be considered when developing reimbursement programmes. The incidence of comorbidities increases along with the age of the patients both in the study group and the general Polish population. If concomitant disorders are present, there are usually more than 2 diseases in a patient. The most frequent concomitant chronic diseases are ischemic heart disease, arterial hypertension and diabetes. Patients over the age of 65 were most frequent in the population taken into palliative home care.

The most common primary neoplasm diagnoses in palliative home care patients were lung cancer and colorectal cancer, which corresponds to the cancer prevalence in the general population. Primary cancer location, except upper gastrointestinal tract and prostate, was not related to the number of concomitant diseases.

References

- 1.Clark D, Wright M. Great Britain: Open University Press; 2003. Transitions in end of life care: hospice and related developments in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palliative care in the European Union. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/studiesdownload.html?languageDocument=EN&file=21421, 20.04. 2012, page 24 (14 April 2012, date last accessed)

- 3.Rocafort J, Rocafort J, Centeno C. Houston: IAHPC Press; 2007. Atlas of palliative care in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciałkowska-Rysz A, Dzierżanowski T. The appraisal of the situation of the paliative care in Poland in 2011. Med Paliat. 2011;4:214–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The health status of Polish population in 2009. Central Statistical Office in Poland http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/PUBL_ZO_stan_zdrowia_2009.pdf. (19 April 2012, date last accessed)

- 6.Polakowska M, Piotrowski W. Incidence of diabetes in the Polish population Results of the Multicenter Polish Population Health Status Study – WOBASZ. Pol Arch Med Wew. 2011;121:156–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liebhart J, Malolepszy J, Wojtyniak B, Pisiewicz K, Plusa T, Gladysz U. Prevalence and risk factors for asthma in Poland: results from the PMSEAD Study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007;17:367–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niżankowska-Mogilnicka E, Mejza F, Buist AS, et al. The incidence and prevalence of COPD and smoking in Malopolska region – results of the BOLD study in Poland. Pol Arch Med Wew. 2007;117:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yancik R, Ganz PA, Varricchio CG, et al. Perspectives on comorbidity and cancer in older patients: approaches to expand the knowledge base. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1147–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair H, Shu XO, Volmink J, Romieu I, Spiegelman D. Cohort studies around the world: methodologies, research questions and integration to address the emerging global epidemic of chronic diseases. Public Health. 2012;126:202–5. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Didkowska J, Wojciechowska U, Zatoński W. Cancer in Poland 2009. http://www.onkologia.org.pl/doc/Nowotw2009.pdf (19 April 2012, date last accessed) [PubMed]

- 12.Yancik R, Havlik RJ, Wesley MN, et al. Cancer and comorbidity in older patients: a descriptive profile. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pergolizzi J, Böger RH, Budd K, et al. Opioids and the management of chronic severe pain in the elderly: consensus statement of an international expert panel with fokus on the six clinically most often used World Health Organization step III opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone) Pain Practice. 2008;8:287–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2008.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piwońska A, Piotrowski W, Broda G. Ten year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in the Polish population and medical care. Results of the WOBASZ study. Kardiol Pol. 2010;68:672–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandosz P, O'Flaherty M, Drygas W, et al. Decline in mortality from coronary heart disease in Poland after socioeconomic transformation: modelling study. BMJ. 2012;344:d8136. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8136. (11 April 2012, date last accessed) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization – NCD Country Profiles. 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241502283_eng.pdf. (24 April 2012 date last accessed)

- 17.Poznańska A, Wojtyniak B, Seroka W. Main causes of death among Polish population in 2030. Przegl Epidemiol. 2011;65:483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Górecka D. Patients with chronic lung diseases have right to palliative care – recommendation of Polish Respiratory Society. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2012;80:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jassem E, Batura-Gabryel H, Cofta S. Recommendations of PTChP regarding palliative care in chronic respiratory diseases. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2011;80:41–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wooldridge J, Anderson C, Perry MC. Corticosteroids in advanced cancer. Oncology. 2001;15:225–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercadante S, Fulfaro F, Casuccio A. The use of corticosteroids in home palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:386–9. doi: 10.1007/s005200000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glicksman AS, Rawson RW. Diabetes and altered carbohydrate metabolism in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1956;9:1127–34. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195611/12)9:6<1127::aid-cncr2820090610>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutton LM, Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC. Management of terminal cancer in elderly patients. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:149–57. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alhuwalia IB, Mack KA, Murphy W, et al. Site-specific prevalence of selected chronic disease-related characteristics – Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2001. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003;52:1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barford KL, D'Olimpio JT. Symptom management in geriatric oncology: practical treatment considerations and current challenges. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9:204–14. doi: 10.1007/s11864-008-0062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu YL, Sun Q, Shan GL, et al. A case-control study on risk factors of breast cancer in China. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:303–9. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.28558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klimczak A, Kempińska-Mirosławska B, Mik M, Dziki Ł, Dziki A. Incidence of colorectal cancer in Poland in 1999-2008. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:673–8. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.24138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowalczyk M, Banach M, Mikhailidis DP, Rysz J. Erythropoietin update 2011. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:RA240–7. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]