Abstract

During kidney development the cap mesenchyme progenitor cells both self renew and differentiate into nephrons. The balance between renewal and differentiation determines the final nephron count, which is of considerable medical importance. An important goal is to create a precise genetic definition of the early differentiation of cap mesenchyme progenitors. We used RNA-Seq to transcriptional profile the cap mesenchyme progenitors and their first epithelial derivative, the renal vesicles. The results provide a global view of the changing gene expression program during this key period, defining expression levels for all transcription factors, growth factors, and receptors. The RNA-Seq was performed using two different biochemistries, with one examining only polyadenylated RNA and the other total RNA. This allowed the analysis of noncanonical transcripts, which for many genes were more abundant than standard exonic RNAs. Since a large fraction of enhancers are now known to be transcribed the results also provide global maps of potential enhancers. Further, the RNA-Seq data defined hundreds of novel splice patterns and large numbers of new genes. Particularly striking was the extensive sense/antisense transcription and changing RNA processing complexities of the Hox clusters.

Keywords: kidney development, RNA-Seq, Hox genes, renal vesicle, cap mesenchyme, induction

Introduction

The kidney provides an excellent model system for the study of organogenesis. Early in kidney development the ureteric bud (UB) is induced by the metanephric mesenchyme to extend from the nephric duct and to undergo an elaborate branching morphogenesis, eventually giving rise to the collecting duct system (for a review see (Costantini and Kopan, 2010)). In turn cap mesenchyme (CM), which surrounds the UB tips, is induced to form nephrons, the functional units of the kidney. The CM consists of progenitor cells that both self renew and differentiate to give rise sequentially to renal aggregates, renal vesicles, comma-shaped bodies, and S-shaped bodies, which elongate, segment, and further differentiate to make nephrons (Boyle et al., 2008; Kobayashi et al., 2008). The CM balance between self renewal and differentiation is critically important in determining the final nephron count, which can have significant health consequences (Keller et al., 2003; Poladia et al., 2006a). In addition, the differentiation of the CM to form renal vesicles is the fascinating first step in the conversion of an amorphous mesenchyme cloud into the intricate complexity of the nephron.

Some of the genetic regulators of CM differentiation have been elegantly defined through the analysis of mutant mice. In the absence of WNT9B there is a failure of CM differentiation, and no renal vesicles are made (Carroll et al., 2005). In contrast, the absence of the transcription factor SIX2 results in the rapid exhaustion of CM, as it prematurely converts to renal vesicles (Self et al., 2006). The balance between the up regulation of WNT signaling and the down regulation of Six2 expression appears to provide key control of CM differentiation. In addition, a number of other genes play important roles in maintaining the CM population, including Sall1 (Nishinakamura and Osafune, 2006), Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 (Poladia et al., 2006b), Fgf8 (Grieshammer et al., 2005; Perantoni et al., 2005), Wt1 (Hartwig et al., 2010) and Bmp7 (Dudley et al., 1999; Luo et al., 1995).

In situ hybridizations have been used to follow the changing gene expression patterns as CM is induced to form RV (Mugford et al., 2009). The uninduced CM expresses Six2 and Cited1, but not Wnt4, while the induced CM expresses Six2 and Wnt4, but not Cited1. A number of new genes are expressed as the RV forms. Perhaps surprising, the initial RV is already polarized with respect to gene expression, presaging the eventual proximal-distal segmentation of the nephron. The distal domain of the RV is marked by expression of Lhx1, Dll1, Dkk1,jag1, Bmp2 and Brn1, while the proximal domain expresses Tmem100 and Wt1 (Georgas et al., 2009; Kobayashi et al., 2005; Mugford et al., 2009; Nakai et al., 2003).

Laser capture micro-dissections (LCM) coupled with microarrays have been used to more globally define the changing gene expression state as the CM differentiates into RV (Brunskill et al., 2008). This strategy yields a list of over one thousand genes that undergo differential expression during this process, and gives a much more complete picture of the gene expression program driving early nephrogenesis.

Gene expression profiling with RNA-Seq is superior to microarrays in several respects (Wang et al., 2009). First, RNA-Seq can examine all transcripts, while microarrays are limited by their probe representation, which is based on a priori assumptions of gene composition. Second, RNA-Seq is better for defining alternative RNA processing events, which are very common and can be of considerable importance. It now reported that over 90% of genes can give rise to alternate transcripts, with an average of 6–7 distinct RNA isoforms per allele (Birney et al., 2007). Third, RNA-Seq offers a much wider dynamic range (Mortazavi et al., 2008). Microarrays have detection problems with very low abundance transcripts because of background issues, and for highly expressed genes they can saturate, causing loss of linear response. With RNA-Seq only sequence reads that can be properly aligned with the genome are used, thereby eliminating nonspecific background. In addition, RNA-Seq results are extremely accurate in measuring transcript levels as determined by qPCR validation (Nagalakshmi et al., 2008) and RNA spike controls (Mortazavi et al., 2008).

In this report we further extend the global analysis of CM differentiation by using RNA-Seq. The results give a dramatically improved characterization of the changing gene expression programs that propel the formation of the renal vesicle. Of note, we observed significant shifts in RNA processing that were not detected with microarrays. In addition new genes and noncoding transcripts were defined. Indeed, we found an abundance of transcription outside of canonical exons. In particular, the Hox clusters showed striking complexity and fluidity in expression, suggesting that perhaps they should be considered more as supergenes rather than collections of individual genes.

We also designed the RNA-Seq experiments to provide a global map of transcriptionally active potential gene enhancers in CM and RV cells. Surprisingly, a number of studies have now shown that a significant fraction of enhancers are themselves transcribed. For example, it was shown that neuronal enhancers induced by membrane depolarization bind p300/CBP, as well as H3K4me1 modified histones, and about half are transcribed, giving rise to short (under 2 KB) bidirectional transcripts designated enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) (Kim et al., 2010). Evidence suggested that most are not polyadenylated. In another study looking at the transcriptional response to macrophage activation it was shown that PolII the transcription of enhancers gave rise to polyadenylated transcripts that were unstable (De Santa et al., 2010). To better define the extragenic transcription of CM and RV cells we therefore performed the RNA-Seq using two approaches, one examining only polyadenylated RNA and the other sequencing total RNA. The results provided a detailed genomic view of the transcribed sequences driving CM and RV gene expression, and the polyadenylation status of their transcripts.

Material and methods

Purification of CM and RV cells

GFP positive cells were purified from BAC-transgenic Crym-GFP mouse kidneys as previously described (Brunskill et al., 2008; Brunskill et al., 2011). Single cell suspensions were made enzymatically and subjected to fluorescent activated cell sorting. At PI the CM cells show the strongest GFP signal, while at P4, following CM depletion, most of the remaining GFP resides in RV cells. RNA was purified as previously described (Brunskill et al., 2011).

RNA-Seq

RNAs were processed according to recommended procedures, using the Illumina TruSeq and Nugen Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 methods. Sequencing was carried out using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 system according to Illumina protocols.

Data analysis

To analyze the RNA-Seq data we used an approach that is similar to the model developed by Mortazavi et al. in their ERANGE (http://woldlab.caltech.edu/rnaseq/) RNAseq analysis pipeline. Per-spot sequence reads were aligned allowing up to 2 mismatches and 10-multiple mappings to both genome and transcriptome targets. We used both Bowtie (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml) and Tophat (http://tophat.cbcb.umd.edu/manual.html) for genome and transcriptome alignments. Bam files were downloaded into AvadisNGS. Data was RPKM normalized and filtered on expression, removing those that failed to have a minimum of 3 RPKM in at least one sample. The Audic Claverie test was used to find differentially expressed genes, P value ≤ 0.01, with Benjamini Hochberg FDR multiple testing correction.

RNA-Seq data is available on the GUDMAP resource (GUDMAP.ORG).

Results

We used RNA-Seq to define the changing gene expression state of CM cells as they differentiate into RV. Postnatal CM and RV cells were isolated using BAC-transgenic Crym-GFP mice, as previously described (Brunskill et al., 2008). Crym shows strong specific expression in the CM, similar to Six2. We isolated CM cells from postnatal day 1 (P1) mice by rapid enzymatic dissociation of kidney cells, followed by FACS purification of GFP positive cells, using stringent gating to select only cells with strong GFP expression. It has been previously shown that in the days following birth there is a burst of nephrogenesis that consumes the remaining CM (Hartman et al., 2007). We were able to use this postnatal CM depletion to purify RV at P4. At this time point the CM is absent, but there is lingering low level GFP signal in the CM derivatives, primarily RV, but also including small amounts of comma and S-shaped bodies. This labeling is presumably the result of perdurance, or residual GFP from the CM that is not yet degraded.

As mentioned, we used two different technologies to perform RNA-Seq analysis, in order to define both polyadenylated and nonpolyadenylated transcripts. The Illumina TruSeq system includes an initial selection for PolyA+ RNA. These transcripts were then reverse transcribed with random primers in order to provide representation across the entire breadth of the PolyA+ RNAs. We also performed RNA-Seq using the Nugen Ovation RNA-Seq System V2, which uses a combination of dT and random primers for the initial reverse transcription, giving full representation of both polyA+ and polyA- RNA.

The resulting RNA-Seq data was analyzed with AvadisNGS software. The four sets of RNA-Seq data combined for 78,727,800 aligned sequences, or approximately 20 million reads each. Data was RPKM (reads per kilobase per million) normalized, and filtered to require a minimum of three RPKM in at least one sample, which equals approximately 3–6 transcripts per cell (Li et al., 2010; Mortazavi et al., 2008).

The TruSeq (PolyA+) and Nugen (random primed) datasets were examined separately. While PolyA+ RNA-Seq gave sequences that primarily aligned with canonical exons, random primer based RNA-Seq resulted in a majority of reads that, interestingly, aligned outside of defined exons. The PolyA+ and random primed data sets could be pooled, but there are significant advantages to be gained by separate analyses. The comparison of the two sets of results using independent RNA-Seq technologies provides a global cross validation of identified differentially expressed genes, and can also be used to determine the polyadenylation state of RNAs.

The Audic Claverie test was used to find differentially expressed genes, P value ≤ 0.01, with Benjamini Hochberg FDR multiple testing correction, and minimum two fold change, giving a list of 1,377 genes for the polyA+ data and 1,484 genes for random primed RNA-Seq data. The two methods showed good agreement, with 1,003 genes in common for the two lists. Many of the differences could be accounted for by genes that were just above the two fold change cutoff with one method and were just missing this cutoff with the other.

We focused on the PolyA+ RNA-Seq data, further filtering the differential expressed gene lists by requiring a congruent minimum 1.5 fold change in the random primed RNA-Seq data. Again, by performing the RNA-Seq with two independent technologies, and requiring a consistent change in gene expression, we provide a global validation of results. This gave lists of 424 genes with elevated expression in CM (Table S1), and 692 genes with elevated expression in RV (Table S2). In total these represented approximately the top eleven hundred genes with changing expression as CM differentiates into RV.

Genes with elevated CM expression

The list of genes with elevated expression in CM includes many previously shown expressed in this compartment, including Cited1, Six2, Gdnf, Crym, and Eya1, providing historic validation of the data set. This gene list can be examined from many different perspectives. First, it is interesting to consider the genes that showed the greatest fold change (FC). For example, Fgf20 gave about 100 fold higher expression in CM compared to RV. Of interest, Fgf1 (29 FC) and Fgf10 (3 FC) were also higher in CM. Other genes with strongly elevated expression in CM included Pdyn (70 FC), which encodes a propeptide for opioid ligands, Siglecg (123 FC, sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin G), Saa1 (55 FC, serum amyloid A1), and the transcription factors Meox1 (38 FC), Meox2 (18 FC), and Phf19 (50 FC), and the cytokine I133 (33 FC).

The genes with higher CM expression were also functionally analyzed with ToppGene (http://toppgene.cchmc.org/enrichment.jsp). This provided lists of genes with specific molecular functions, such as phosphatases, kinases, growth factors, heparin binding, and many more. ToppGene also identified CM highly expressed genes associated with specific biological processes, including cell adhesion, neuron development, ossification, and muscle development. ToppGene also examined the evolutionarily conserved transcription factor binding sites in the promoters of the coordinately regulated CM highly expressed genes and defined candidate transcription factors involved in their regulation (Table S3).

Another useful perspective is provided by ranking the genes with elevated CM expression according to expression level. The underlying assumption is that higher expression levels can correlate with greater functional significance. Although clearly not universally true there is some precedent to support this proposition. The most highly expressed transcription factors with elevated CM expression included, with normalized RPKM expression levels in parentheses, Cited1 (118), Six2 (117), Meox1 (47), Srebf1 (28), Meis2 (23), Tshz1 (20), Zhx2 (17), Hoxc8 (17), Meox2 (15), Tef(14), Hoxc4 (13), Hoxc6 (12), Lmx1b (12), Hoxd12 (11) and Foxd2 (11) (Table S4). It is interesting that Cited1 and Six2, two of the transcription factors most strongly associated with cap mesenchyme historically, are at the top of this list. Unexpectedly, four Hox genes that not commonly associated with CM are also on the list, as well as the Hox cofactor Meis2. This suggests important roles for these Hox genes in CM. Other genes included Tshz1, which encodes a teashirt zinc finger and homeobox transcription factor. The Tshz1 mutant mouse suffers perinatal lethality, but no kidney phenotype has been reported (Core et al., 2007). Lmx1b mutant mice show a phenotype similar to human nail patella syndrome, including renal pathology (Chen et al., 1998).

A similar list of growth factor genes with higher CM expression includes Pdgfc (38), Tgbf3 (20), Gdnf (16), Fgf1 (13), Inha (11), Fgf10, (9), Fgf20 (7), Ogn (6), Pgf(6), Ntf3 (5) and Tgfb2 (5). It is known that PDGF signals the stromal compartment, which expresses PDGFRB, while GDNF interacts with the RET receptor on the branching ureteric bud. PGF is related to VEGF and could play a role in recruiting endothelial cells. Inha encodes inhibin, which counteracts activin function.

Of interest, there were 31 genes with higher CM expression encoding proteins with receptor activity. The top fifteen, again ranked by expression level, were Itga8 (62), Ramp2 (55), Fzd2 (51), Cxcr4 (49), Cntfr (47), Slc22a17 (44), Sema4g (34), Unc5c (32), Npr2 (23), Robo2 (20), Mrc2 (17), Ager (16), Trtaf1 (15), Ednra (14), and Tgfbr2 (12). For the complete list see Table S5. This rich set of receptors suggests that the CM is subject to a complex repertoire of signaling inputs. Fzd2, encoding a WNT receptor, is third highest in expression level, consistent with an important role for WNT signaling. Nevertheless, many other receptors show similar levels of expression, suggesting that they too are involved in CM regulation.

It is also interesting to note that AvadisNGS identified 18 “NewGenes” with elevated expression in CM (Table S5). Almost half of these (8/18) were located flanking canonical genes that were also differentially expressed, including Six2, Foxd2, Gm6081, Chd2 and Fgf20. This suggests that they share enhancer elements with the flanking genes, and/or were involved in their regulation. Two of the “NewGenes” were actually found to represent novel exons that spliced to previously characterized genes. All but three of the “NewGenes” showed evidence of splicing, with splice junction sequences spanning introns.

Genes with higher expression in RV

A ToppGene (http://toppgene.cchmc.org/) analysis of the 692 genes with elevated expression in RV identified several interesting molecular functions (Table S6). Microtubule motor activity was increased dramatically, with thirteen kinesin genes showing greater RV expression. There were 44 genes encoding proteins with calcium ion binding function, and 27 genes encoding actin binding proteins. Six up-regulated genes encoded WNT binding proteins (SFRP2, FZD10, WLS, FZD8, CTHRC1 and FZD5). Other molecular functions increased in RV included integrin binding, semaphorin receptor binding, and extracellular matrix binding.

ToppGene also identified over fifty biological processes that were strongly up-regulated in RV, with P-values of essentially zero (Table S6). Many were related to mitosis, consistent with increased cell division as the CM is induced to make RV. Another prominent category was cell adhesion, as would be expected with the mesenchyme to epithelia transformation taking place. Other identified interesting biological processes included vasculature development, neuron development, the BMP signaling pathway, and the canonical WNT receptor signaling pathway. See Table S6 for complete lists of RV activated molecular functions and biological processes, with associated gene lists.

Genes involved in Notch signaling were prominent among those up-regulated in RV, including Notch1 (5.2 FC), Jag1 (17.4 FC), Dll1 (10.2 FC), Mam12 (3.1 FC) and the Notch targets Hes5 (110 FC), Hey1 (4.1 FC), Hey2 (2.9 FC), and Gata3 (67 FC). This is consistent with a prominent role for Notch signaling in CM differentiation.

In total there were 107 genes with over a ten fold higher expression in RV than CM. Some of the more interesting included Pde4c (76 FC), a cAMP specific phosphodiesterase, Sim1 (35 FC) and Sim2 (68 FC), orthologs of the Drosophila single minded master regulator of development, Dkk1(25 FC), Lhx1(19 FC), Npy (33 FC), lama1(17 FC) and Osr2 (57 FC). See supplementary data Table S2 for the complete list of genes.

As for the CM, it is also useful to rank the genes with elevated expression in the RV according to expression level. The top 20 genes encoding proteins with transcription activity, again with RPKM expression levels in parentheses, were Pax8 (117), Lhx1 (108), Sox11 (80), Hey1 (78), Emx2 (66), Id1 (65), Notch1 (49), Hnf1b (45), Mafb (43), Pou3f3 (34), Sox9 (26), Aatf (24), Dach1 (23), Foxm1 (23), Irx3 (20), Mycl1 (14), Sim1 (12), Tbx2 (12), Gata3 (12), and Tcfap2b. For a complete list see Table S7. The top twenty genes encoding proteins with receptor binding activity, including growth factors, were Wnt4 (75), Dll1 (71), Gja1 (69), Lama1 (50), Dkk1 (39), Bmp4 (38), Lama4 (37), Npy (36), Cxcl14 (32), Itga6 (29), Npnt (28), Cthrc1 (27), Itga3 (26), Efnb2 (25), Epha4 (23), Bmp2 (21), Myo5b (19), Sema4d (18) and Nppc (17) (for a complete list see Table S8). And the most highly expressed genes encoding receptors with RV enrichment were Gpr125 (62), Notch1 (49), Clec18a (48), Plxnd1 (34), Ngfr (32), Oxtr (31), Grb7 (30), Lrp4 (29), Itga6 (29), Cxcr7 (27), Robo1 (27), Itga3 (26), Lsr (25), Ptgfrn (24), Epha4 (23), Cxadr (22), Sema3g (21), Unc5b (21), Sema4d (18) and Fgfr4 (18) (Table S9).

Seven “Newgenes” with elevated RV expression were found (Table S2). One of these (NewGene94) was actually found to represent a 13 exon addition to the 3’ end of ptpn3. The NewGene251 was spliced and polyadenylated and near Tmem132b, which also showed higher RV expression. Similarly, NewGene141 was spliced and polyadenylated and near Gm5972 and Dkk1, which also had elevated RV expression. The remaining four NewGenes were all polyadenylated, and NewGene684 and NewGene245 showed splicing, while NewGene762 and 685 did not.

Opposite strand transcription and alternative RNA processing

Two of the considerable advantages of RNA-Seq over microarrays are, first, the ability to identify all transcripts, without the a priori assumptions required for array design, and second, the ability to easily define alternative RNA processing patterns. In addition, as mentioned previously, by performing the RNA-Seq analysis of CM and RV both with and without a polyA selection step we were able to generate dual data sets that revealed the polyadenylation state of sequenced transcripts. To illustrate the informative power of the RNA-Seq data generated we present views of five transcription factor genes of known importance in kidney development.

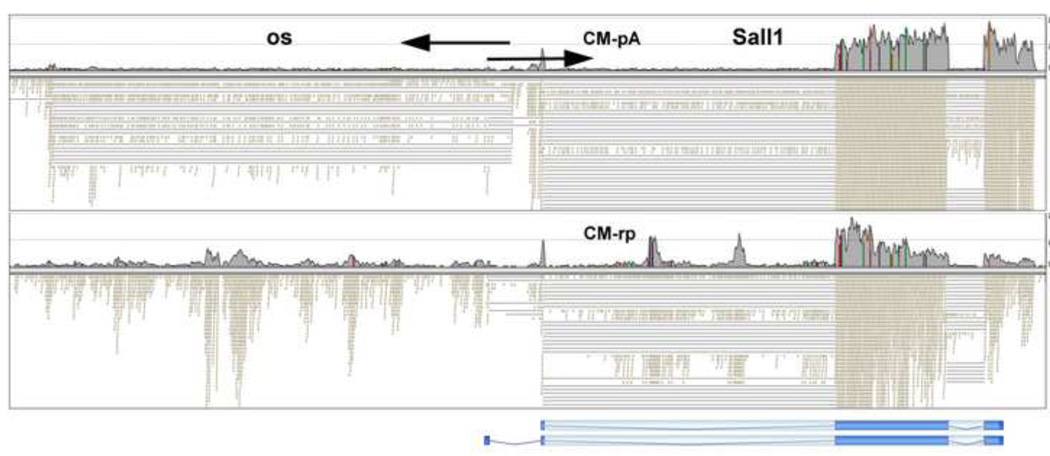

Heterozygous mutation of Sall1 in humans leads to Townes-Brocks syndrome, and homozygous mutation in mice results in severe renal dysgenesis, with only rudimentary kidneys present (Nishinakamura et al., 2001). RNA-Seq showed strong expression of Sall1 in CM, as well as RV. The CM-pA (poly A selected) data showed high read counts for the exonic regions of Sall1, as expected (Fig. 1). Of interest, however, the random primer RNA-Seq data, without polyA selection, (CM-rp), showed additional strong peaks, with two residing in an intron of Sall1 and others in the 5’ flanking region. Some of these likely mark the locations of enhancers and represent eRNAs.

Fig. 1. Salll transcription.

The top panel shows the abundance of RNA-Seq reads in the CM in region of the Sall1 gene as measured with technology using poly A (pA) selection. In the bottom panel a different RNA-Seq technology was used, with random primers (rp), and not involving poly A selection. At the bottom the positions of the Sall1 exons are shown, aligned from the UCSC Genome Browser. Lighter shading denotes coding regions. In the top panel most of the polyadenylated transcripts are found to correspond to positions of the Sall1 exons, as might be expected. In the bottom panel, however, it is apparent that there are also abundant non-polyadenylated transcripts coming from both intron and 5’ flanking regions of the gene, as marked by arrowheads.

A higher magnification view of the RNA-Seq data from the Sall1 locus shows individual RNA-Seq reads as small rectangles (Fig. 2). When a sequence read spans an intron the two ends of the sequence are connected by a line, which represents the position of the intron. The sequences at the splice junctions, which of course have the consensus GT.…AG, can be used to determine the orientation of the transcript. For the Sall1 gene the canonical splice pattern was observed, with two alternative promoter sequences used, as previously defined in the UCSC Genome Browser view of this chromosomal region, shown aligned at the bottom of the Fig. 2. Of interest, however, there was also an opposite strand (os) polyA+, spliced transcript that was partially overlapping with Sall1 at its 5’ end. The predominant splice form of this os transcript appeared to have a single intron. It is also interesting to note that the random primed Nugen technology detected abundant transcripts that were not spliced. The dual data sets suggests that there are two classes of transcripts derived from the 5’ region of the Sall1 gene, with some not spliced and not polyadenylated, and others spliced and polyadenylated.

Fig. 2. Flanking opposite strand transcripts from the Sall1 gene.

Each small rectangle represents an RNA-Seq sequence read. When a sequence shows homology to two separate genomic regions they are separated by a line, representing an intron. The sequences at the splice junctions allow the processed transcript to be assigned to one of the two DNA strands. Immediately 5’ of the Sall1 gene there are opposite strand (os) spliced and polyadenylated transcripts, as shown in the top panel. The bottom panel shows that there are also abundant nonpolyadenylated transcripts derived from this region. The arrows mark the transcriptional orientations of the Sall1 and os transcripts. There is overlap at the 5’ ends for some transcripts.

Wtl is another transcription factor gene required for normal kidney development (Kreidberg et al., 1993). As for Sall1, Wt1 is expressed in both CM and RV. The CM-pA data showed the highest number of RNA-Seq reads localized at Wt1 exons, as might be expected (Fig. 3). Of considerable interest, however, the CM-rp data showed that many of the transcripts from this locus were not polyadenylated and were from intronic regions of the gene. Some of the peaks of non-polyadenylated transcripts are marked with arrowheads in Fig. 3. It is indeed quite surprising to identify such a transcriptional profile, with more nonpolyadenylated RNA generated from introns than there are canonical exonic transcripts. These observations raise a number of questions. If these do indeed represent eRNA, from enhancers, then they are likely relatively unstable (Kim et al., 2010). PolyA increases RNA stability, and even RNA with short polyA tails is subject to exonuclease degradation (Guhaniyogi and Brewer, 2001). If these transcripts are more abundant than the standard exon transcripts, despite their instability, then they must be transcribed at a much greater rate. How this transcription is achieved without interfering with expression of Wt1 is an interesting puzzle. In addition, when transcription initiates at an intronic position and is headed in the 3’ direction there is the question of how it is terminated after a short distance, while transcription starting at the 5’ end of the gene reads the entire length through to the 3’ end of the gene.

Fig. 3. Transcription of the Wt1 gene.

The polyadenylated transcripts from the Wt1 gene correspond primarily to the positions of canonical exons (top panel). The arrow marks an exon that is often skipped. The bottom panel shows, however, that there are abundant nonpolyadenylated transcripts that arise from intronic regions of the Wt1 gene, with some of the more prominent peaks marked by arrowheads. The positions of the Wt1 exons are shown at the bottom.

A closer view of the Wt1 RNA-Seq data showed that exon 5 is indeed often skipped, with sequences from the splice donor junction of exon four extending directly to the spice acceptor of exon six. In addition, also as previously described, there are two alternative splice donor sequences for the Wt1 exon 9, separated by nine bases, and both are used in the CM as well as the RV.

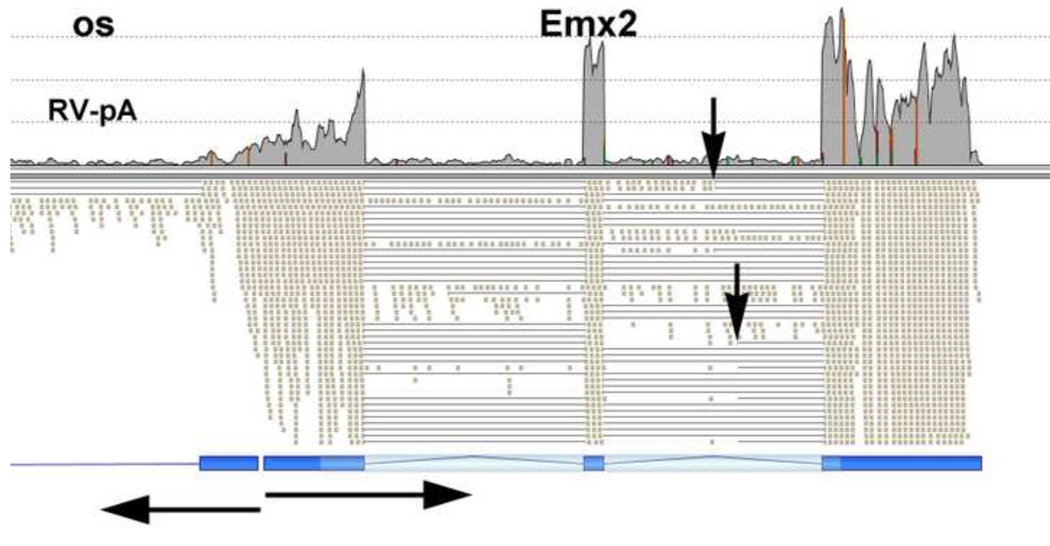

The Emx2 transcription factor gene is also required for normal kidney development. Emx2 was differentially expressed, with many more RNA-Seq reads for RV than CM. Of interest, Emx2 also showed an opposite strand transcript that was similarly regulated, with much higher expression in RV (Fig. 4). This opposite strand Emx2 transcript has been previously shown to play a role in the regulation of Emx2 expression (Lee et al., 2006). A higher magnification view of the RNA-Seq data for Emx2 showed the presence of multiple transcript isoforms used in the RV (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Transcription of the Emx2 gene.

There were many more transcripts from Emx2 in RV (bottom panels) than CM. The bottom shows the positions of the three canonical exons of Emx2, from the UCSC genome browser, on the right, and the exons of a noncoding opposite strand transcript on the left. There were many nonpolyadenylated transcripts that did not align with exon positions. Arrows show orientations and start sites for the Emx2 and os transcripts.

Fig. 5. Alternative splicing of the Emx2 gene.

Vertical arrows mark two alternative splice sites observed for the Emx2 gene in the RV. Horizontal arrows mark orientations and transcription start sites for the Emx2 and os transcripts.

The Six2 gene encodes yet another transcription factor required for kidney development (Self et al., 2006). Six2, as expected, showed high expression in the CM and much reduced expression in the RV (Fig. 6). This gene, like Sall1 and Emx2, also has an opposite strand transcript. As for Six2, it showed much higher expression in CM. The close up view of the RNA-Seq data shows the simple two exon splice form of the Six2 gene, but a strikingly complex set of possible splicing patterns for the opposite strand transcript (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6. Transcription of the Six2 gene.

As expected, Six2 was much more strongly expressed in CM (top panels) than RV. Of interest, however, there were abundant transcripts, both polyadenylated and nonpolyadenylated, derived from the 5’ flanking region.

Fig. 7. Complex splicing patterns of the Six2 os transcripts.

The Six2 gene showed a strict compliance with the two exon structure predicted from the UCSC genome browser, aligned at the bottom. The 5’ flanking noncoding opposite strand transcript, however, showed a complex set of alternative processing options.

Lhx1 provides another interesting example of the power of the RNA-Seq data. Metanephric mesenchyme specific mutation of Lhx1 results in arrest at the RV stage of development (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Potter et al., 2007). This gene, as expected from previous studies, showed strongly elevated expression in the RV compartment compared to CM (19 fold change). Lhx1, once again, showed the presence of an opposite strand, spliced, large intergenic noncoding (Line) transcript. As for Lhx1 it showed much higher expression in RV than CM. The splicing pattern for Lhx1 was, as predicted, with all five exons consistently included. The opposite strand transcript, however, showed greater variability in splicing patterns (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Transcription of the Lhx1 gene.

Lhx1 and a flanking opposite strand noncoding gene were coordinately regulated, with high expression in RV and very low expression in CM. The Lhx1 gene showed very consistent RNA processing, using the canonical five exons, as aligned at the bottom. The opposite strand transcript showed two predominant splice forms.

In summary, the RNA-Seq data shows expression levels for genes, as well as changing RNA processing patterns, the presence of abundant nonpolyadenylated transcripts, and the surprisingly frequent presence of flanking opposite strand LincRNAs with concordant regulation. It is interesting to note that LincRNAs have previously been associated with enhancer function, activating adjacent genes (Orom etal., 2010; Wang etal., 2011). While only five genes of particular interest are described here in detail, the RNA-Seq data set defines these parameters for all genes.

Novel Splice Forms

The RNA-Seq data can be scanned by AvadisNGS to identify novel splice forms. A total of 242 expressed genes were found with new splice junctions, using a minimum requirement of five sequence replicates per splice type. Several genes showed more than one original splice pattern, with a total of 364 new splices found (Table S10).

It is interesting to consider Pax2 in detail. Several alternative splice forms have been previously described, including the skipping of exon 6, the skipping of a possible exon within intron 9, the inclusion of intron 9, and the use of two different splice acceptors for exon 11 (Busse etal., 2009; Dressier and Douglass, 1992; Tavassoli et al., 1997; Ward et al., 1994). In both the CM and RV we observed that exon 6 was usually skipped and both splice acceptors for exon 11 were used. Also, intron 9 and the possible exon within it were always spliced out. In addition, however, we observed new splice forms. Exon 10 was occasionally spliced out in both CM (5/113 splices) and RV (13/108). In CM we found three transcripts with both exons 9 and 10 removed. We also saw rare skipping of exon 2 in the CM (~1% of splices) and RV (~5% of splices). This is particularly interesting because skipping of exon 2 causes a frameshift, which is not the case for exons 6, 9 and 10. In addition there were two alternate splice acceptors at the 5’ end of exon 2, separated by three bases, and each were used in both CM and RV. Most striking, however, was the use of a novel 5’ exon, located about 10 kb 5’ of the canonical Pax2 gene, which then spliced into the standard Pax2 exon 1. It included an in frame ATG, resulting in the addition of 34 amino acids to the PAX2 protein. This novel 5’ exon was more heavily used in the CM (27 splice reads) than RV (only 2 splice junction reads).

Interesting alternative RNA processing was also observed for Pax 8, which showed use of two different splice acceptors for intron 3 in the RV, separated by 3 bases, making exon 4 encode one extra amino acid. This splice was used 20/116 times in RV and 0/32 in CM. In addition exon 9 was sometimes skipped in both CM (9/36) and RV (16/150), resulting in a 69 amino acid deletion, but no frameshift.

Other genes of particular interest with novel splice junctions included Crym, Eya4, Robo1, Robo2, and Hox genes.

Hox SuperGenes

The Hox genes are known to play important and redundant roles in kidney development. While homozygous Hoxa11 or Hoxd11 mice show relatively normal kidney development (Davis and Capecchi, 1994; Small and Potter, 1993), the double homozygous mutant mice for both genes have very rudimentary kidneys with multiple developmental defects (Davis et al., 1995; Patterson et al., 2001). The further removal of the Hoxc11 paralogs results in early failure of early metanephric kidney induction (Wellik et al., 2002). In addition the HoxlO paralogous group has been shown to play a critical role in the development of the cortical stroma (Yallowitz et al., 2011). Many other Hox genes are expressed in the developing kidney (Patterson and Potter, 2004) and likely have functions that remain to be determined. We therefore paid particular attention to Hox transcription in the CM and RV.

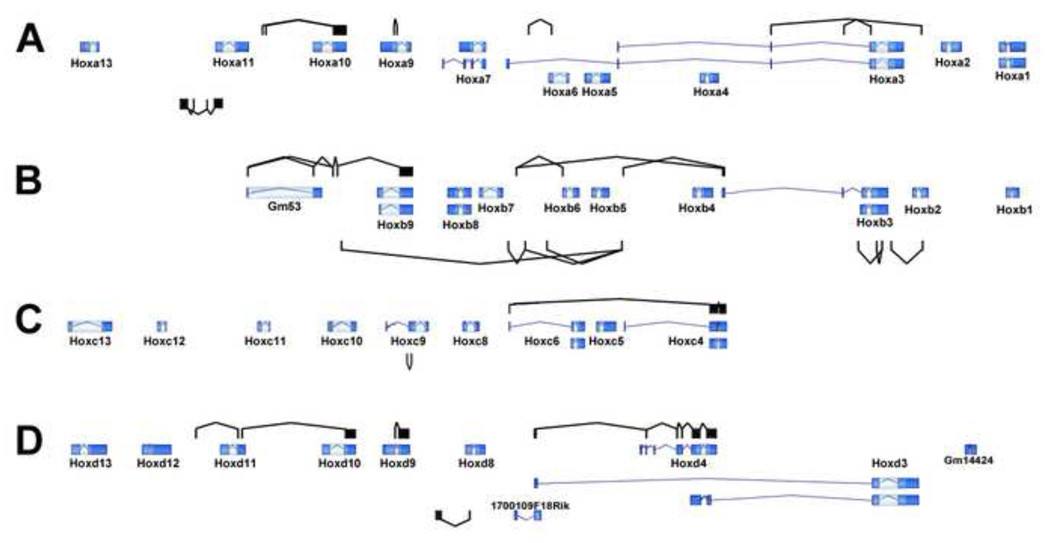

HoxA cluster

A view of the transcript profile from the entire HoxA cluster is shown in Fig. 9. The UCSC Genome Browser view of this chromosomal region is aligned at the bottom. The genes are shown in reverse order, with Hoxa13 at the left, as this gives the view with transcription for all HoxA genes going from left to right. Each of the HoxA genes, except Hoxa1 and Hoxa13, were expressed in both the CM and RV. It is interesting to note that transcripts were not restricted to the standard Hox exon positions. This is particularly true for the RNA-Seq using random primers, with both intronic and intergenic regions showing abundant transcripts. The CM and RV showed quite similar patterns of HoxA expression when viewed at the level of total transcript distribution.

Fig. 9. Transcription of the HoxA cluster.

Transcription was widespread across the HoxA cluster, with only the extreme 3’ and 5’ Hoxa1 and Hoxa13 showing absence of expression in both the CM and RV. In addition there were abundant intergenic transcripts, with some of these clearly polyadenylated. The canonical HoxA exons, as defined by the UCSC genome browser, are shown aligned along the bottom.

Many of the genes on the HoxA cluster showed interesting, and in some cases quite surprising, patterns of RNA processing. In both the CM and RV we observed abundant Hoxa11 opposite strand transcripts, with multiple splice forms, as we have previously described (Bodenmiller et al., 2002; Hsieh-Li et al., 1995). For the Hoxa10 gene we observed three alternative splice isoforms. A commonly observed splice pattern connected the two canonical Hoxa10 exons, as displayed in the UCSC genome browser (Fig. 10). At least as often, however, especially in CM, we observed use of an alternate more 5’ first exon, which was then spliced directly to the final exon. This novel first exon used two possible splice donor sequences. The more 3’ donor site results in a transcript (ENSMUST00000121043) that encodes a truncated 94 amino acid protein, (compared to the standard 416 aa HOXA11 protein) while the more 5’ slice site (ENSMUST00000142611) gives no protein product. It is interesting to note that we also found one splice junction that connected this alternate 5’ exon of Hoxa10 to the sequences of the first exon of Hoxa9 (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Alternative processing of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10.

The Hoxa10 gene showed frequent use of an alternate 5’ exon, with two possible splice donor sites (arrows). These spliced to the canonical 3’ Hoxa10 exon to give rise to truncated or no protein (see text). We observed one case where this alternate Hoxa10 exon spliced directly to the Hoxa9 gene (triangle). There was an alternate intron within the first exon of Hoxa9 that was only used in RV (arrowhead).

The predominant CM splice forms for Hoxa9 were standard, involving the two canonical exons for this gene. There was, however, an interesting developmental switch in processing, with RV showing the presence of an intron within the first exon, which was often spliced out. This transcript (ENSMUST00000114425) (or, for example, EST AA987018) encodes a truncated protein of 105 amino acids, compared to the normal HOXA9 protein of 271 amino acids. We observed 7 of these splice junctions in RV, compared to 29 standard splice events.

For Hoxa6 we observed a splice form present only in RV that connected a novel first exon to the standard Hoxa6 first exon. We also observed new splice forms for the Hoxa3 gene. A summary of the multiple alternative processing events observed for the HoxA cluster is shown in Fig. 11A.

Fig. 11. Splicing summary for the Hox clusters.

The canonical exon configurations for Hox clusters A–D, as taken from the UCSC genome browser, are shown. Additional observed splicing patterns are shown above (sense orientation) and below (antisense). The extensive transcription of each cluster, combined with the elaborate splicing patterns summarized in this figure, with sense and antisense, as well as intergenic processing that can sometimes span multiple standard Hox genes, suggests a supergene organization.

HoxB cluster

The HoxB cluster was particularly rich in unusual transcription and RNA processing. As for the HoxA cluster all of the HoxB genes showed good expression in both RV and CM, except for the members of the first and last paralogous groups (Hoxb1 and Hoxb13), which showed no detectable expression. Transcripts were positioned across the breadth of the Hoxb9 to Hoxb2 region, especially when assayed with random primer RNA-Seq (Fig. 12). Hoxb13 is not included in this figure, as it lies far 5’ and showed no expression. It is interesting to note the abundance of intergenic transcripts between Hoxb3 and Hoxb5, with most appearing to be without polyadenylation. Intergenic trancripts were also numerous in the region between Hoxb6 and Hoxb7, and these showed strong representation in the polyA+ selected RNA-Seq data, indicating polyadenylation.

Fig. 12. Transcription of the HoxB cluster.

As for the HoxA cluster, transcripts were found spanning the HoxB cluster in both CM and RV. Only Hoxb1 and Hoxb13, which is located very 5’ and not shown here, were not expressed. Once again many of the transcripts were intergenic, with some polyadenylated and most not. Standard exons as defined by the UCSC genome browser are aligned along the bottom.

Hoxb9 showed use of an alternate 5’ exon for 25% (14/56) of splice junctions. Indeed, there was a complex pattern of possible splice forms in this region, with some connecting sequences of the EST Gm53 to the second exon of Hoxb9.

The Hoxb6 gene showed the expected splicing of the two standard exons, but in addition there was extensive splicing of a more 5’ exon into the standard Hoxb6 first exon, with two possible splice acceptors used, separated by 32 bases. One of these splices is represented in the EST database by Hoxb6-002 (transcript ENSMUST00000173432). Of special interest, this alternate Hoxb6 first exon in about half of transcripts was spliced beyond the Hoxb 4,5,6 genes, to join with what is generally considered the standard first Hoxb3 exon.

Just 3’ of the Hoxb5 gene there was another novel exon whose transcripts spliced into the canonical Hoxb3 first exon. Therefore Hoxb3 has three possible first exons, with one located between Hoxb6 and Hoxb7, another between Hoxb4 and Hoxb5, and then the standard Hoxb3 5’ exon.

In addition there was extensive antisense transcription of the HoxB cluster. One noncoding antisense transcript spanned both the Hoxb5 and Hoxb6 genes (Riken EST 0610040B09Rik-001).

The elaborate set of observed sense and antisense HoxB cluster splice forms are summarized in Fig. 11B. The picture that emerges is remarkably complex, and distinct from the view that is found in many textbooks, which typically show Hox clusters consisting of a series of simple two exon genes. Instead it is apparent that the HoxB cluster is broadly transcribed from both strands, and that these RNAs undergo elaborate processing to give rise to the many transcripts observed. Indeed, in a sense the HoxB cluster should be considered a single supergene capable of giving rise to a variety of splice form products, instead of a collection of individual genes.

HoxC cluster

In sharp contrast with the A, B and D clusters, the C cluster showed very little unexpected transcription. There was an antisense transcript from the 5’ region of Hoxc9, and the first exon of Hoxc6 was observed to sometimes splice into the second exon of Hoxc4, as summarized in Fig. 11C. Hoxc12 and l3 were not expressed. Of interest, Hoxc4,5,6, and 8 all showed two to three fold elevated expression in CM compared to RV.

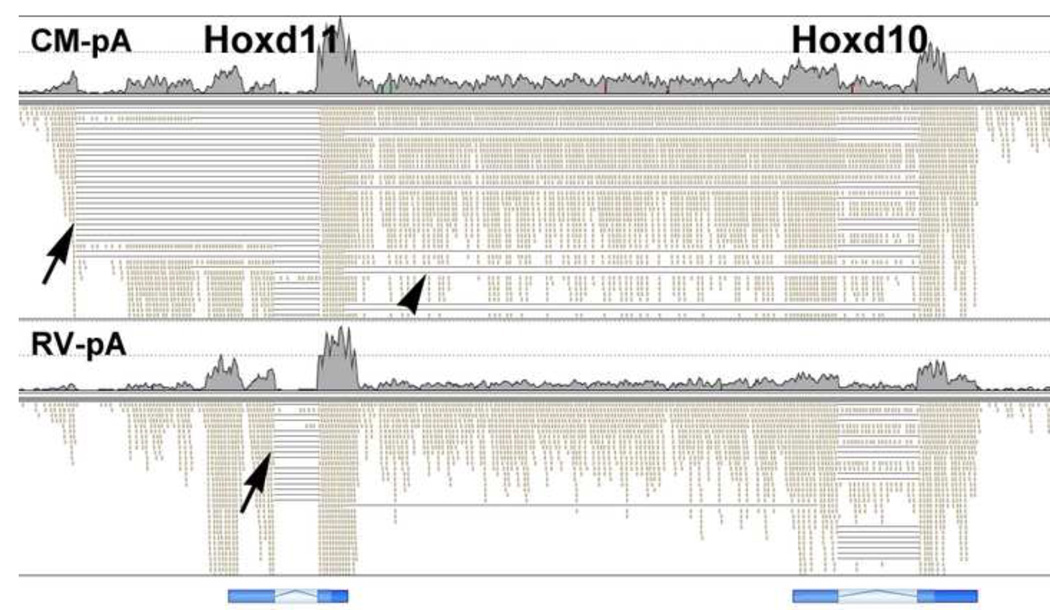

HoxD cluster

The HoxD cluster, like the HoxA and HoxB clusters, showed many complex splice forms. In CM the Hoxd11 gene primarily used an alternate first exon, which then spliced into the last exon (Fig. 13). It is interesting to note that this novel splice results in a frameshift and therefore gives a noncoding RNA. In contrast, the RV showed standard exon usage for Hoxd11. This further illustrates the power of RNA-Seq, as microarrays would simply show expression for the Hoxd11 gene in both CM and RV, while RNA-Seq shows that the predominant CM splice form is actually noncoding.

Fig. 13. Hoxd10 and Hoxd11 splicing patterns.

For the RV we observed almost exclusively standard exon splicing events, connecting the two canonical exons of each gene. In the CM, however, there was frequent use of an alternate Hoxd11 5’ exon, which resulted in a frameshift when spliced to the 3’ exon and therefore was noncoding (arrows). In the CM we also observe extensive splicing of the 3’ Hoxd11 sequences to the 3’ exon of Hoxd10 (arrowhead). It is also interesting to note that there were many intergenic polyadenylated transcripts that did not appear to be spliced.

Of particular interest, we observed many splice events that connected the last exon of Hoxd11 to the last exon of Hoxd10. This intergenic splicing of two Hox genes emphasizes the interconnectedness of the exons of the Hox clusters.

For Hoxd9 we observed use of a novel splice site in CM, between exons one and two, which results in the inclusion of an extra 179 bases in the final transcript, giving a frameshift in the normal open reading frame, and the encoding of a truncated protein that does not include the homeodomain. This novel splice form accounts for approximately 50% of CM transcripts, but was not detected (0/28 sequences spanning the Hoxd9 splice site) for RV (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Alternative splicing of Hoxd9 in CM.

The RV showed strictly expected splicing of Hoxd9, but in the CM we observed about 50% use of an alternate splice donor that resulted in the inclusion of an additional 179 bases, causing a frameshift and the production of a truncated protein without a homeodomain (arrow).

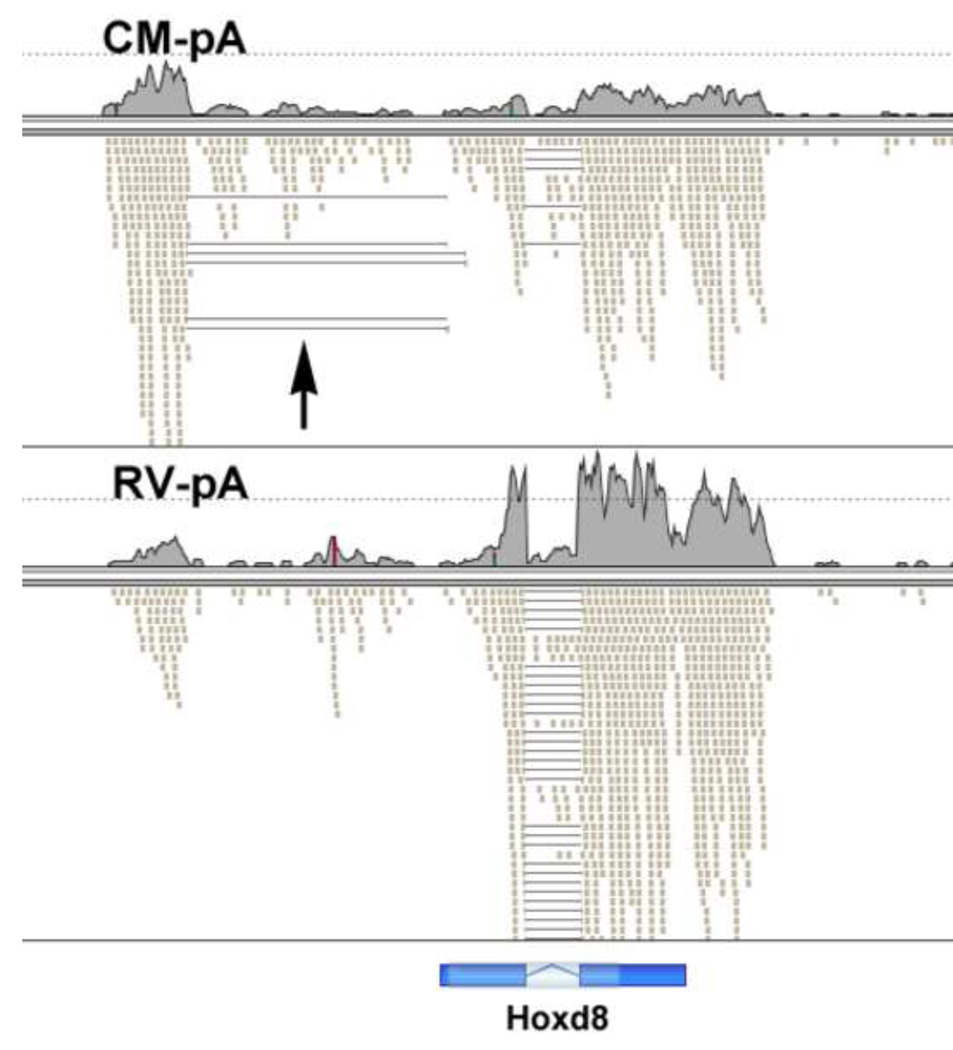

For the Hoxd8 gene there was an antisense transcript, in two splice forms, that overlapped its 5’ end, which was much more abundant in CM than RV (Fig. 15). In this case, as we have previously reported for Hoxa10 (Hsieh-Li et al., 1995), there appeared to be a reciprocal relationship. In the RV the Hoxd8 transcripts were abundant and the antisense transcripts rare, while the CM showed more abundant antisense transcripts and reduced Hoxd8 RNA.

Fig. 15. Hoxd8 antisense transcription.

We observed antisense transcripts for Hoxd8 that were much more abundant in the CM than RV. Of interest, the Hoxd8 transcripts showed a reciprocal relationship, being more abundant in the RV than CM.

The Hoxd3 5’ exon also overlapped an antisense transcript, previously described as 1700109F 18Rik. This spliced and polyadenylated (seen with PolyA+ selected technology) transcript was detected in CM but not RV. Surprisingly, all of these 17 splice junctions sequenced from both CM and RV showed that the most 5’ Hoxd3 exon was spliced to the second exon of Hoxd4. None of them were spliced to the canonical next Hoxd3 exon (Fig. 16). Several mouse ESTs also show this surprising splice form (BX517876, AI791102, CJ054205). The next exon of Hoxd4 was skipped about half of the time, in both CM and RV. This is the third exon of Hoxd4 as presented on the UCSC genome browser.

Fig. 16. Unorthodox splicing in the vicinity of Hoxd3 gene.

Particularly noteworthy are the splicing of the Hoxd3 most 3’ exon to the second exon of Hoxd4, and the presence of an internal intron with the canonical fourth Hoxd4 exon.

We observed that the next exon of Hoxd4, the canonical fourth exon, includes an internal intron that was universally spliced out in both the CM and RV in 28/28 of splice junction reads. There is a mouse EST (CJ054205), which shows similar splicing within this exon, Ensembl Hoxd3-002, transcript ID ENSMUST00000144040, designated as noncoding.

For Hoxd3 we observed that some transcripts initiated within the Hoxd4 gene, as previously reported, while most included only the final two canonical exons. A summary of the multiple splice forms observed for the HoxD cluster is shown in Fig. 13 D.

Discussion

A key event in kidney development is the differentiation of CM to RV. The CM progenitors are induced to undergo a mesenchyme to epithelia transformation, and generate a series of transitional structures that give rise to nephrons (Boyle et al., 2008; Kobayashi et al., 2008). An important goal is to create a precise genetic definition of this remarkable process.

We used RNA-Seq to better define the gene expression states of the CM and its first epithelial differentiated derivative, the RV. The resulting dataset provides a global view of early nephrogenesis, describing the expression levels of essentially all genes, including transcription factors, growth factors and receptors. By examining the differences in gene expression between the CM and RV one defines the changes in gene expression that drive the early stages of nephron formation. The RNA-Seq analysis of this process presented here serves to significantly extend earlier studies using primarily in situ hybridizations (Georgas et al., 2009; Mugford et al., 2009), microarrays (Brunskill et al., 2008; Brunskill et al., 2011; Schmidt-Ott et al., 2007), or RNA-Seq analysis of total kidneys (Thiagarajan et al., 2011). For example, the RNA-Seq data identified novel splice junctions for 242 genes, several of which have been previously shown to play important roles in kidney development.

In addition, we carried out the RNA-Seq with two independent technologies, which allowed the identification of transcripts both with and without polyadenylation. Since many enhancers are actively transcribed (De Santa et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010) the results generated genome wide maps of potential expressed enhancers in CM and RV. The transcript profiles observed were often very striking, with many more RNAs present from non-exonic regions than from bona fide exons. In some cases these putative enhancer transcripts were polyadenylated, but in most cases they were not. Their considerable abundance, often outnumbering exon transcripts, coupled with their instability (De Santa et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010), argues that they are transcribed at very high rates. The view of the transcriptome that emerges is rather distinct from the classical linear model of genomic organization. A major remaining challenge is to define the functions of the emerging transcriptional complexity of the genome (Birney et al., 2007; Kapranov et al., 2007; Prasanth and Spector, 2007).

We observed an interesting pattern of transcription for several genes of known importance in kidney development. For Sall1, Emx2, Lxh1 and Six2 there were flanking opposite strands transcripts that were spliced, noncoding and showed coordinate regulation. For example the Six2 opposite strand transcripts were much more abundant in CM than RV, as for Six2. This contrasts with many sense/antisense gene expression pairs that have been shown to have reciprocal expression patterns (Hsieh-Li et al., 1995; Lehner et al., 2002). While the functions of several large noncoding RNAs, including XIST, TSIX, HOTAIR and AIR, have been characterized (Mattick, 2009), and large numbers of such RNAs have been identified (Khalil et al., 2009), the functions of most of these transcripts remain to be defined (Guttman and Rinn, 2012). It is interesting to note that approximately 1,600 K4–K36 transcribed domains have been identified in the mouse genome, compared with 2,500 in the human genome, representing possible LincRNAs (Guttman et al., 2009; Orom et al., 2010). Our RNA-Seq data showed about 400 expressed noncoding, spliced LincRNAS in the CM and RV samples.

As previously mentioned, a significant fraction of enhancers have been shown to give rise to short bidirectional transcripts, (Kim et al., 2010), perhaps the result of CBP/p300 binding PolII, which then transcribes outwards in both directions. In principle the opposite strand transcripts of Sall1, Emx2, Lxh1 and Six2 could be the result of a similar process, although the processing and polyadenylation of the opposite strands RNAs is distinct from what is observed for eRNAs.

The RNA-Seq data from the Hox clusters was particularly remarkable. The results of this study confirm and extend previous work showing an astonishing transcriptional complexity for the Hox clusters. We first reported the extensive antisense transcription of Hoxa11, with a striking complementary expression pattern suggesting a possible regulatory function (Hsieh-Li et al., 1995). A subsequent in silico analysis of the EST database showed a surprising number of unorthodox Hox transcriptional possibilities, including antisense and polycistronic, with some having evolutionary conservation suggesting function (Mainguy et al., 2007). Another elegant study used tiling arrays to detect extensive Hox transcription in human skin fibroblasts derived from different anterior/posterior domains (Rinn et al., 2007). Of particular interest, a noncoding RNA designated HOTAIR, from the HoxC cluster, was shown to regulate HoxD genes in trans, although this human HOTAIR function does not appear to be conserved in mice (Schorderet and Duboule, 2011).

In this report we describe in elaborate detail the changing transcription and RNA processing of the four Hox clusters as a function of differentiation of the CM into RV. There were a surprisingly large number of Hox genes expressed in both CM and RV. For example, for the HoxA cluster all genes were expressed except those at the extreme ends, Hoxa1 and Hoxa13. The other clusters showed equivalent patterns. On the HoxB cluster only Hoxb1 and Hoxb13 were not expressed. And for the HoxC luster, which does not include genes for paralogs 1–3, only the extreme 5– genes Hoxc12 and Hoxc13 were not expressed. Similarly, for the HoxD cluster, which lacks paralogs for the 1 and 2 groups, only the extreme 5’ Hoxd13 gene was not expressed. In general the expression levels for the Hox genes were relatively unchanged in the CM and RV, although Hoxc4, 6, 8 and Hoxd12 were somewhat higher in CM. In total there were 28 Hox genes expressed in both CM and RV. There was clearly no dramatic shift in the expression code of Hox genes at the transcriptional level as CM differentiated into RV.

The observed Hox expression patterns in CM and RV were distinct from the “bimodal” patterns that have been previously described. For example in human fibroblasts there was a single boundary point between Hoxa7 and Hoxa9, with only Hox genes downstream of this point [Hoxa1–7] expressed in the skin of the foot, while only Hox genes upstream of this boundary (Hoxa 9–13) were expressed in the lung (Rinn et al., 2007). Somewhat similar bimodal blocks were observed for the HoxD cluster in the developing spinal cord (Tschopp et al., 2012). In contrast we observed broad expression of Hox genes in both CM and RV, with only genes at the extreme 5’and 3’ ends not transcribed.

We did, however, observe some striking changes in Hox gene RNA processing. In many cases the CM and RV showed distinct Hox gene exon/intron patterns. Particularly noteworthy, the resulting transcripts often have dramatically different functionality. For example the Hoxd11 gene primarily used an alternate 5’ exon in the CM, resulting in a noncoding RNA, while in the RV there was canonical exon usage. Changes of this sort are best defined with RNA-Seq technology and have not been previously characterized in studies using microarrays.

The view of the Hox clusters that emerges is extraordinary. They are almost devoid of repeat sequences, which have been estimated to make up as much as two thirds of the human genome (de Koning et al., 2011), arguing for important functionality of even the intergenic regions. Consistent with this, there is strong evolutionary conservation of noncoding sequences of Hox clusters (Lee et al., 2006). In addition, as shown in this report, there is pervasive transcription that effectively covers the entire clusters, giving rise to both sense and antisense, spliced and non-spliced, polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs, that remain to be fully defined. The resulting transcripts include microRNAs, Line RNAs, enhancer RNAs, canonical Hox mRNAs, and likely novel categories of RNAs. Hox clusters are clearly much more complicated than simple collections of genes and associated enhancers.

The genetic dissection of Hox function is therefore particularly challenging. The evolutionary conservation of the Hox clusters as intact units is likely a result of their sophisticated organization. The Cre-Lox mediated deletion of multi-gene blocks from Hox clusters therefore disrupts functionality in a manner that is difficult to interpret. A preferred approach would use finer genetic modifications, including combinations of small frameshift mutations and/or microdeletions. With this strategy it might be possible to tease out not only paralog and flanking Hox gene functional redundancies, but also the roles of the myriad of other transcripts that Hox clusters give rise to.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the assistance of Shawn Smith for carrying out the Nugen amplification reactions, and the contributions of Bruce Aronow and Phil Dexheimer in the initial stages of data analysis. This work was supported by a grant from NIH (RC4DK090891).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Eric W Brunskill, Email: Eric.brunskill@cchmc.org.

S. Steven Potter, Email: Steven.potter@cchmc.org.

References

- Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigo R, Gingeras TR, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Snyder M, Dermitzakis ET, Thurman RE, Kuehn MS, Taylor CM, Neph S, Koch CM, Asthana S, Malhotra A, Adzhubei I, Greenbaum JA, Andrews RM, Flicek P, Boyle PJ, Cao H, Carter NP, Clelland GK, Davis S, Day N, Dhami P, Dillon SC, Dorschner MO, Fiegler H, Giresi PG, Goldy J, Hawrylycz M, Haydock A, Humbert R, James KD, Johnson BE, Johnson EM, Frum TT, Rosenzweig ER, Karnani N, Lee K, Lefebvre GC, Navas PA, Neri F, Parker SC, Sabo PJ, Sandstrom R, Shafer A, Vetrie D, Weaver M, Wilcox S, Yu M, Collins FS, Dekker J, Lieb JD, Tullius TD, Crawford GE, Sunyaev S, Noble WS, Dunham I, Denoeud F, Reymond A, Kapranov P, Rozowsky J, Zheng D, Castelo R, Frankish A, Harrow J, Ghosh S, Sandelin A, Hofacker IL, Baertsch R, Keefe D, Dike S, Cheng J, Hirsch HA, Sekinger EA, Lagarde J, Abril JF, Shahab A, Flamm C, Fried C, Hackermuller J, Hertel J, Lindemeyer M, Missal K, Tanzer A, Washietl S, Korbel J, Emanuelsson 0, Pedersen JS, Holroyd N, Taylor R, Swarbreck D, Matthews N, Dickson MC, Thomas DJ, Weirauch MT, Gilbert J, Drenkow J, Bell I, Zhao X, Srinivasan KG, Sung WK, Ooi HS, Chiu KP, Foissac S, Alioto T, Brent M, Pachter L, Tress ML, Valencia A, Choo SW, Choo CY, Ucla C, Manzano C, Wyss C, Cheung E, Clark TG, Brown JB, Ganesh M, Patel S, Tammana H, Chrast J, Henrichsen CN, Kai C, Kawai J, Nagalakshmi U, Wu J, Lian Z, Lian J, Newburger P, Zhang X, Bickel P, Mattick JS, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Weissman S, Hubbard T, Myers RM, Rogers J, Stadler PF, Lowe TM, Wei CL, Ruan Y, Struhl K, Gerstein M, Antonarakis SE, Fu Y, Green ED, Karaoz U, Siepel A, Taylor J, Liefer LA, Wetterstrand KA, Good PJ, Feingold EA, Guyer MS, Cooper GM, Asimenos G, Dewey CN, Hou M, Nikolaev S, Montoya-Burgos JI, Loytynoja A, Whelan S, Pardi F, Massingham T, Huang H, Zhang NR, Holmes I, Mullikin JC, Ureta-Vidal A, Paten B, Seringhaus M, Church D, Rosenbloom K, Kent WJ, Stone EA, Batzoglou S, Goldman N, Hardison RC, Haussler D, Miller W, Sidow A, Trinklein ND, Zhang ZD, Barrera L, Stuart R, King DC, Ameur A, Enroth S, Bieda MC, Kim J, Bhinge AA, Jiang N, Liu J, Yao F, Vega VB, Lee CW, Ng P, Yang A, Moqtaderi Z, Zhu Z, Xu X, Squazzo S, Oberley MJ, Inman D, Singer MA, Richmond TA, Munn KJ, Rada-Iglesias A, Wallerman O, Komorowski J, Fowler JC, Couttet P, Bruce AW, Dovey OM, Ellis PD, Langford CF, Nix DA, Euskirchen G, Hartman S, Urban AE, Kraus P, Van Calcar S, Heintzman N, Kim TH, Wang K, Qu C, Hon G, Luna R, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Aldred SF, Cooper SJ, Halees A, Lin JM, Shulha HP, Xu M, Haidar JN, Yu Y, Iyer VR, Green RD, Wadelius C, Farnham PJ, Ren B, Harte RA, Hinrichs AS, Trumbower H, Clawson H, Hillman-Jackson J, Zweig AS, Smith K, Thakkapallayil A, Barber G, Kuhn RM, Karolchik D, Armengol L, Bird CP, de Bakker PI, Kern AD, Lopez-Bigas N, Martin JD, Stranger BE, Woodroffe A, Davydov E, Dimas A, Eyras E, Hallgrimsdottir IB, Huppert J, Zody MC, Abecasis GR, Estivill X, Bouffard GG, Guan X, Hansen NF, Idol JR, Maduro VV, Maskeri B, McDowell JC, Park M, Thomas PJ, Young AC, Blakesley RW, Muzny DM, Sodergren E, Wheeler DA, Worley KC, Jiang H, Weinstock GM, Gibbs RA, Graves T, Fulton R, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, Clamp M, Cuff J, Gnerre S, Jaffe DB, Chang JL, Lindblad-Toh K, Lander ES, Koriabine M, Nefedov M, Osoegawa K, Yoshinaga Y, Zhu B, de Jong PJ. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmiller DM, Baxter CS, Hansen DV, Potter SS. Phylogenetic analysis of Hoxa 11 sequences reveals absence of transposable elements, conservation of transcription factor binding sites, and suggests antisense coding function. DNA Seq. 2002;13:77–83. doi: 10.1080/10425170290029981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle S, Misfeldt A, Chandler KJ, Deal KK, Southard-Smith EM, Mortlock DP, Baldwin HS, de Caestecker M. Fate mapping using Cited 1-CreERT2 mice demonstrates that the cap mesenchyme contains self-renewing progenitor cells and gives rise exclusively to nephronic epithelia. Dev Biol. 2008;313:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill EW, Aronow BJ, Georgas K, Rumballe B, Valerius MT, Aronow J, Kaimal V, Jegga AG, Yu J, Grimmond S, McMahon AP, Patterson LT, Little MH, Potter SS. Atlas of gene expression in the developing kidney at microanatomic resolution. Dev Cell. 2008;15:781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill EW, Lai HL, Jamison DC, Potter SS, Patterson LT. Microarrays and RNA-Seq identify molecular mechanisms driving the end of nephron production. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse A, Rietz A, Schwartz S, Thiel E, Keilholz U. An intron 9 containing splice variant of PAX2. J Transl Med. 2009;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, Majumdar A, McMahon AP. Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev Cell. 2005;9:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lun Y, Ovchinnikov D, Kokubo H, Oberg KC, Pepicelli CV, Gan L, Lee B, Johnson RL. Limb and kidney defects in Lmxlb mutant mice suggest an involvement of LMX1B in human nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core N, Caubit X, Metchat A, Boned A, Djabali M, Fasano L. Tshz1 is required for axial skeleton, soft palate and middle ear development in mice. Dev Biol. 2007;308:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini F, Kopan R. Patterning a complex organ: branching morphogenesis and nephron segmentation in kidney development. Dev Cell. 2010;18:698–712. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AP, Capecchi MR. Axial homeosis and appendicular skeleton defects in mice with a targeted disruption of hoxd-11. Development. 1994;120:2187–2198. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AP, Witte DP, Hsieh-Li HM, Potter SS, Capecchi MR. Absence of radius and ulna in mice lacking hoxa-11 and hoxd-11. Nature. 1995;375:791–795. doi: 10.1038/375791a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Koning AP, Gu W, Castoe TA, Batzer MA, Pollock DD. Repetitive elements may comprise over two-thirds of the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:el002384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santa F, Barozzi I, Mietton F, Ghisletti S, Polletti S, Tusi BK, Muller H, Ragoussis J, Wei CL, Natoli G. A large fraction of extragenic RNA pol II transcription sites overlap enhancers. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:el000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressier GR, Douglass EC. Pax-2 is a DNA-binding protein expressed in embryonic kidney and Wilms tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1179–1183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley AT, Godin RE, Robertson EJ. Interaction between FGF and BMP signaling pathways regulates development of metanephric mesenchyme. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1601–1613. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgas K, Rumballe B, Valerius MT, Chiu HS, Thiagarajan RD, Lesieur E, Aronow BJ, Brunskill EW, Combes AN, Tang D, Taylor D, Grimmond SM, Potter SS, McMahon AP, Little MH. Analysis of early nephron patterning reveals a role for distal RV proliferation in fusion to the ureteric tip via a cap mesenchyme-derived connecting segment. Dev Biol. 2009;332:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshammer U, Cebrian C, Ilagan R, Meyers E, Herzlinger D, Martin GR. FGF8 is required for cell survival at distinct stages of nephrogenesis and for regulation of gene expression in nascent nephrons. Development. 2005;132:3847–3857. doi: 10.1242/dev.01944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhaniyogi J, Brewer G. Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Gene. 2001;265:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00350-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, French C, Lin MF, Feldser D, Huarte M, Zuk 0, Carey BW, Cassady JP, Cabili MN, Jaenisch R, Mikkelsen TS, Jacks T, Hacohen N, Bernstein BE, Kellis M, Regev A, Rinn JL, Lander ES. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Rinn JL. Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature. 2012;482:339–346. doi: 10.1038/nature10887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman HA, Lai HL, Patterson LT. Cessation of renal morphogenesis in mice. Dev Biol. 2007;310:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig S, Ho J, Pandey P, Macisaac K, Taglienti M, Xiang M, Alterovitz G, Ramoni M, Fraenkel E, Kreidberg JA. Genomic characterization of Wilms' tumor suppressor 1 targets in nephron progenitor cells during kidney development. Development. 2010;137:1189–1203. doi: 10.1242/dev.045732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh-Li HM, Witte DP, Weinstein M, Branford W, Li H, Small K, Potter SS. Hoxa 11 structure, extensive antisense transcription, and function in male and female fertility. Development. 1995;121:1373–1385. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P, Willingham AT, Gingeras TR. Genome-wide transcription and the implications for genomic organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:413–423. doi: 10.1038/nrg2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller G, Zimmer G, Mall G, Ritz E, Amann K. Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:101–108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, Garber M, Raj A, Rivea Morales D, Thomas K, Presser A, Bernstein BE, van Oudenaarden A, Regev A, Lander ES, Rinn JL. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11667–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, Harmin DA, Laptewicz M, Barbara-Haley K, Kuersten S, Markenscoff-Papadimitriou E, Kuhl D, Bito H, Worley PF, Kreiman G, Greenberg ME. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature. 2010;465:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature09033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Kwan KM, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP, Mendelsohn CL, Behringer RR. Distinct and sequential tissue-specific activities of the LIM-class homeobox gene Lim1 for tubular morphogenesis during kidney development. Development. 2005;132:2809–2823. doi: 10.1242/dev.01858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Valerius MT, Mugford JW, Carroll TJ, Self M, Oliver G, McMahon AP. Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreidberg JA, Sariola H, Loring JM, Maeda M, Pelletier J, Housman D, Jaenisch R. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AP, Koh EG, Tay A, Brenner S, Venkatesh B. Highly conserved syntenic blocks at the vertebrate Hox loci and conserved regulatory elements within and outside Hox gene clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6994–6999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601492103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner B, Williams G, Campbell RD, Sanderson CM. Antisense transcripts in the human genome. Trends Genet. 2002;18:63–65. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Ruotti V, Stewart RM, Thomson JA, Dewey CN. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:493–500. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G, Hofmann C, Bronckers AL, Sohocki M, Bradley A, Karsenty G. BMP-7 is an inducer of nephrogenesis, and is also required for eye development and skeletal patterning. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2808–2820. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainguy G, Koster J, Woltering J, Jansen H, Durston A. Extensive polycistronism and antisense transcription in the mammalian Hox clusters. PLoS One. 2007;2:e356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick JS. The genetic signatures of noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:el000459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugford JW, Yu J, Kobayashi A, McMahon AP. High-resolution gene expression analysis of the developing mouse kidney defines novel cellular compartments within the nephron progenitor population. Dev Biol. 2009;333:312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagalakshmi U, Wang Z, Waern K, Shou C, Raha D, Gerstein M, Snyder M. The transcriptional landscape of the yeast genome defined by RNA sequencing. Science. 2008;320:1344–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.1158441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai S, Sugitani Y, Sato H, Ito S, Miura Y, Ogawa M, Nishi M, Jishage K, Minowa O, Noda T. Crucial roles of Brnl in distal tubule formation and function in mouse kidney. Development. 2003;130:4751–4759. doi: 10.1242/dev.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishinakamura R, Matsumoto Y, Nakao K, Nakamura K, Sato A, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Scully S, Lacey DL, Katsuki M, Asashima M, Yokota T. Murine homolog of SALL1 is essential for ureteric bud invasion in kidney development. Development. 2001;128:3105–3115. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishinakamura R, Osafune K. Essential roles of Sail family genes in kidney development. J Physiol Sci. 2006;56:131–136. doi: 10.2170/physiolsci.M95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orom UA, Derrien T, Beringer M, Gumireddy K, Gardini A, Bussotti G, Lai F, Zytnicki M, Notredame C, Huang Q, Guigo R, Shiekhattar R. Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell. 2010;143:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson LT, Pembaur M, Potter SS. Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 regulate branching morphogenesis of the ureteric bud in the developing kidney. Development. 2001;128:2153–2161. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson LT, Potter SS. Atlas of Hox gene expression in the developing kidney. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:771–779. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perantoni AO, Timofeeva O, Naillat F, Richman C, Pajni-Underwood S, Wilson C, Vainio S, Dove LF, Lewandoski M. Inactivation of FGF8 in early mesoderm reveals an essential role in kidney development. Development. 2005;132:3859–3871. doi: 10.1242/dev.01945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poladia DP, Kish K, Kutay B, Bauer J, Baum M, Bates CM. Link between reduced nephron number and hypertension: studies in a mutant mouse model. Pediatr Res. 2006a;59:489–493. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000202764.02295.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poladia DP, Kish K, Kutay B, Hains D, Kegg H, Zhao H, Bates CM. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in the metanephric mesenchyme. Dev Biol. 2006b;291:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter SS, Hartman HA, Kwan KM, Behringer RR, Patterson LT. Laser capture-microarray analysis of Lim1 mutant kidney development. Genesis. 2007;45:432–439. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth KV, Spector DL. Eukaryotic regulatory RNAs: an answer to the 'genome complexity' conundrum. Genes Dev. 2007;21:11–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.1484207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, Chang HY. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Ott KM, Masckauchan TN, Chen X, Hirsh BJ, Sarkar A, Yang J, Paragas N, Wallace VA, Dufort D, Pavlidis P, Jagla B, Kitajewski J, Barasch J. beta-catenin/TCF/Lef controls a differentiation-associated transcriptional program in renal epithelial progenitors. Development. 2007;134:3177–3190. doi: 10.1242/dev.006544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorderet P, Duboule D. Structural and functional differences in the long non-coding RNA hotair in mouse and human. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:el002071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self M, Lagutin OV, Bowling B, Hendrix J, Cai Y, Dressier GR, Oliver G. Six2 is required for suppression of nephrogenesis and progenitor renewal in the developing kidney. EMBO J. 2006;25:5214–5228. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small KM, Potter SS. Homeotic transformations and limb defects in Hox All mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2318–2328. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli K, Ruger W, Horst J. Alternative splicing in PAX2 generates a new reading frame and an extended conserved coding region at the carboxy terminus. Hum Genet. 1997;101:371–375. doi: 10.1007/s004390050644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan RD, Cloonan N, Gardiner BB, Mercer TR, Kolle G, Nourbakhsh E, Wani S, Tang D, Krishnan K, Georgas KM, Rumballe BA, Chiu HS, Steen JA, Mattick JS, Little MH, Grimmond SM. Refining transcriptional programs in kidney development by integration of deep RNA-sequencing and array-based spatial profiling. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:441. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschopp P, Christen AJ, Duboule D. Bimodal control of Hoxd gene transcription in the spinal cord defines two regulatory subclusters. Development. 2012;139:929–939. doi: 10.1242/dev.076794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, Sanyal A, Corces-Zimmerman R, Chen Y, Lajoie BR, Protacio A, Flynn RA, Gupta RA, Wysocka J, Lei M, Dekker J, Helms JA, Chang HY. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward TA, Nebel A, Reeve AE, Eccles MR. Alternative messenger RNA forms and open reading frames within an additional conserved region of the human PAX-2 gene. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1015–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellik DM, Hawkes PJ, Capecchi MR. Hox11 paralogous genes are essential for metanephric kidney induction. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1423–1432. doi: 10.1101/gad.993302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yallowitz AR, Hrycaj SM, Short KM, Smyth IM, Wellik DM. Hox10 genes function in kidney development in the differentiation and integration of the cortical stroma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.