Abstract

Motivation: Due to advances in molecular sequencing and the increasingly rapid collection of molecular data, the field of phyloinformatics is transforming into a computational science. Therefore, new tools are required that can be deployed in supercomputing environments and that scale to hundreds or thousands of cores.

Results: We describe RAxML-Light, a tool for large-scale phylogenetic inference on supercomputers under maximum likelihood. It implements a light-weight checkpointing mechanism, deploys 128-bit (SSE3) and 256-bit (AVX) vector intrinsics, offers two orthogonal memory saving techniques and provides a fine-grain production-level message passing interface parallelization of the likelihood function. To demonstrate scalability and robustness of the code, we inferred a phylogeny on a simulated DNA alignment (1481 taxa, 20 000 000 bp) using 672 cores. This dataset requires one terabyte of RAM to compute the likelihood score on a single tree.

Code Availability: https://github.com/stamatak/RAxML-Light-1.0.5

Data Availability: http://www.exelixis-lab.org/onLineMaterial.tar.bz2

Contact: alexandros.stamatakis@h-its.org

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Phyloinformatics is facing a paradigm shift toward becoming a ‘real’ computational science. Molecular sequencing technologies are developing at a rapid pace, generating enormous amounts of new data. Due to the necessity to process (and store) huge amounts of data, we expect the field to undergo an analogous transition that physics or computational fluid dynamics underwent 20–30 years ago.

Projects such as the 1000 insect transcriptome sequencing project (www.1kite.org) already face these challenges. Such evolutionary studies require software that scales beyond a single node, that can be checkpointed and restarted, and that can accommodate the memory requirements of whole-genome datasets under likelihood-based models. RAxML-Light is a production-level tool for phylogenetic inference on supercomputers that implements new approaches for handling load imbalance, checkpointing and reducing the RAM requirements of likelihood computations. Implementation details are discussed in the online supplement.

2 FEATURES

We briefly discuss the features that distinguish RAxML-Light from standard RAxML, other likelihood-based phylogeny programs, and the BEAGLE library (Ayres et al., 2011). One important feature (in contrast to BEAGLE, MrBayes (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) or GARLI (Zwickl, 2006)) is that RAxML-Light implements a fine-grain message passing interface (MPI) parallelization to compute the likelihood on a single huge dataset and a single tree across several nodes. We introduced the proof-of-concept implementation in (Ott et al., 2007). The work is split by distributing alignment sites or entire partitions (depending on the selected command line options) among processors.

Another essential feature is the light-weight checkpointing and restart capability, that is required on typical HPC systems that have queues with 24- or 48-h run-time limits. Light weight means that only those data-structures are stored in a checkpoint which are really required to restart the code. The design goal is to minimize checkpoint writing/reading times and file sizes.

To the best of our knowledge, RAxML-Light comprises the only fine-grain parallelization of the likelihood function that also incorporates load balance mechanisms as described in (Stamatakis and Ott, 2009) and (Zhang and Stamatakis, 2012). Load imbalance can deteriorate parallel efficiency in partitioned phylogenetic analyzes.

RAxML-Light also contains a production-level implementation of two orthogonal memory saving techniques that can be used simultaneously (described in Izquierdo-Carrasco et al., 2011a,b). These techniques allow for deploying RAxML-Light on systems that do not have enough RAM to store all conditional probability vectors required for likelihood calculations.

Finally, RAxML-Light also uses 256-bit wide AVX vector intrinsics to accelerate likelihood computations on Intel Sandy-Bridge and AMD Bulldozer CPUs that will become available in many HPC systems over the next 2–3 years.

3 PERFORMANCE AND STRESS TESTS

3.1 Parallel scalability

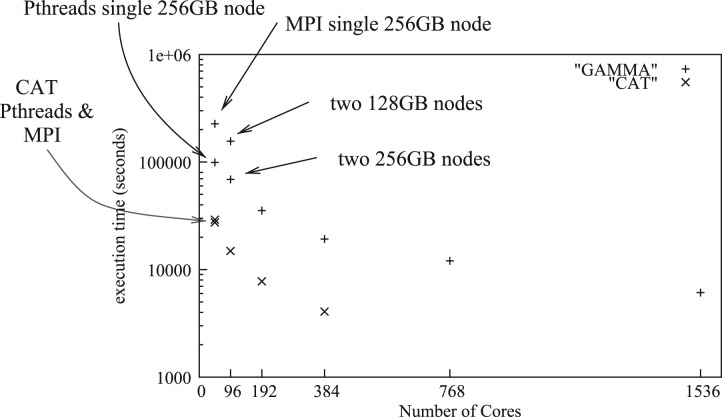

We measured the relative speedup of the MPI version of RAxML-Light on a dataset with 150 taxa and 20 000 000 bp (extracted from the above simulated dataset) on an AMD Magny-Cours-based cluster with a Qlogic Infiniband interconnect and a total of 50 48-core nodes equipped with 128 GB (46 nodes) or 256 GB (4 nodes) of RAM per node. For comparison, we also measured execution times of the PThreads-based version on a stand-alone 48-core AMD server with 256 GB RAM. In Figure 1, we provide execution times for the PThreads and MPI versions on multiples of 48 cores under the CAT (Stamatakis, 2006) and Γ (using four discrete rate categories) models of rate heterogeneity. The test dataset requires almost 256 GB of RAM under Γ which explains the bad initial performance under Γ on one and two cluster nodes. The nodes in the cluster have slightly different swapping configurations than the stand-alone node (same server type) we used. Overall, the code scales well up to 1536 cores. On 1536 cores, RAxML-Light requires <2 h (6108 s) to complete a full tree search under Γ.

Fig. 1.

Parallel execution times of the MPI and PThreads versions under CAT and Γ on a DNA dataset with 150 taxa and 20 000 000 sites

3.2 Load balance

The initial work on improving load balance for partitioned datasets (Stamatakis and Ott, 2009) is hard-coded in RAxML-Light and can improve parallel efficiency by >50%. The recent work on the ‘multi-processor scheduling problem in phylogenetics’ ((Zhang and Stamatakis, 2012), -Q option) should only be applied when the number of partitions/genes is substantially larger than the cores that shall be used. This alternative data distribution scheme improved parallel run times by one order of magnitude on a partitioned protein alignment with 1000 partitions under CAT.

3.3 Computing a terabyte tree

To conduct a thorough stress test, we simulated a DNA alignment with 1481 taxa and 20 000 000 bp using SeqGen (Rambaut and Grass, 1997). The 1481 taxon tree we used to generate the alignment is a ML tree inferred on a real-world single gene dataset. Under the CAT model of rate heterogeneity, this dataset requires about 1 TB of RAM to compute the likelihood on a single tree. We executed a single tree search on 672 cores (14 48-core nodes) which required 40 h to converge for the standard RAxML search algorithm. The relative Robinson–Foulds (RF) distance to the true tree was 7%.

3.4 Computing a 116 334 taxon tree

For the NSF plant tree of life grand challenge project, we deployed the PThreads version (running on a single 48-core node) to perform 100 ML searches (each search starting from distinct randomized stepwise addition order parsimony starting tree) on a real-world DNA alignment (116 334 taxa, 16 079 bp) under CAT and a partitioned model. With the ML search convergence criterion enabled (see Stamatakis, 2011) the runs required two automatic restarts (using appropriate Sun Grid Engine scripts) from checkpoints to complete within three 48 h queue slots. While the runs were successful, the resulting trees did not make ‘biological sense’. This is in part a result of trying to construct, with the data available at the time in GenBank (ca. 2008), alignments with >100 000 species. Viridiplantae did not have data for >100 000 species with any of traditionally well-sampled gene regions. So we had to (1) expand the dataset with less well-sampled gene regions for plants, (2) include ribosomal regions 18S and 26S and (3) include a large fungi outgroup. These complications allowed us to construct a large dataset with >100 000 species but led to some unexpected taxonomic placements. Nonetheless, we make the alignment and trees available for benchmarking purposes.

3.5 Memory saving techniques

The scalability of RAxML-Light is limited by the number of sites in the alignment, because RAxML-Light is parallelized over sites/partitions. Hence, it does not make sense to analyze datasets as the one above (116 334 taxa) in parallel on more than one node. On such gappy datasets with missing data, we can deploy the subtree equality vector technique (-S option) to substantially reduce memory requirements. The key idea of this technique is to keep track of subtrees in partitions (genes) that entirely consist of missing data and omit computing as well as storing the ancestral probability vectors for these ‘empty’ subtrees. In the above case, using -S led to a reduction of RAM requirements from 66 GB down to 26.5 GB. This allowed us to also execute some tree searches on single nodes of the Texas Advanced Computing Center, that only have 32 GB of RAM available. The -S option generally also decreases execution times, because a large number of unecessary computations are omitted (see (Izquierdo-Carrasco et al., 2011a) for performance details). Note that performance of this technique also depends heavily on the memory allocator being used (see Supplementary Material).

We also tested the MPI version of the recomputation technique (with reduction factors of -r 0.2 and -r 0.15) on just a single 48-core node with 256 GB RAM on the dense simulated 1 TB dataset that does not contain any gaps. The recomputation technique saves memory by not storing all ancestral probability vectors, but only a fraction of them as specified by the -r switch (e.g. setting -r 0.2 means that only 20% of the ancestral vectors are stored). When an ancestral vector needs to be read that has not been stored in RAM, we simply recompute it. Evidently, execution times will increase because of recomputations, but the increase is small (≈40%) even when storing only 10% (-r 0.1) of the required vectors in RAM (Izquierdo-Carrasco et al., 2011b). Our tests showed that using the recomputation technique, a dataset requiring 1 TB of RAM can be successfully and correctly analyzed on a single multi-core server with only 256 GB RAM (for additional details see Supplementary Material).

3.6 Vector intrinsics for likelihood

We tested the performance of the AVX-vectorization in RAxML-Light using a DNA dataset with 150 taxa and 1269 bp (1130 distinct site patterns) and a protein dataset with 40 taxa and 1104 bp (958 distinct site patterns) on a single Intel i7-2620M core running at 2.7 GHz. We measured execution times under the CAT and under Γ and averaged execution times over three runs. For reference, we also included the execution times of the standard RAxML version without vectorization in Table 1.

Table 1.

Execution times of unvectorized, SSE3- and AVX-vectorized RAxML versions

| Data | Model | Unvectorized | SSE3 | AVX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | CAT | 100 | 87 | 76 |

| DNA | Γ | 520 | 433 | 353 |

| PROT | CAT | 117 | 83 | 49 |

| PROT | Γ | 423 | 249 | 187 |

Unvectorized execution times have been measured using the standard RAxML version.

4 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

We have presented, RAxML-Light, a scalable, AVX-vectorized and checkpointable open-source code for large-scale phylogenetic inference on supercomputers. User support will be provided through groups.google.com/group/raxml and continued development will be provided through the github repository.

For partitioned whole-genome datasets with thousands of partitions, the code requires some substantial re-engineering (in addition to the techniques presented here) to further reduce communication costs. Under the current fork-join parallelization paradigm (also used in BEAGLE), communication to trigger parallel regions for partitioned whole-genome datasets becomes bandwidth-bound instead of latency-bound. This problem is independent of and orthogonal to the load balance issues discussed here and only became apparent in the course of some currently on-going partitioned whole-genome analyses. We also expect energy efficiency and core failure tolerance to become important future research topics with respect to scaling phylogenetics codes to exascale HPC systems.

Funding: Part of this work was funded by German Science Foundation (DFG) grants STA 860/2 and STA 860/3, the NSF (National Science Foundation) iPlant collaborative, and via institutional funding from the Heidelberg Institute of Theoretical Studies.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Ayres D., et al. BEAGLE: an application programming interface and high-performance computing library for statistical phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 2011;61:170–173. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syr100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo-Carrasco F., et al. Algorithms, data structures, and numerics for likelihood-based phylogenetic inference of huge trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011a;12:470. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo-Carrasco F., et al. Trading memory for running time in phylogenetic likelihood computations. Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies; 2011b. Technical report. [Google Scholar]

- Ott M., et al. Large-scale maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analysis on the IBM BlueGene/L. Proceedings of IEEE/ACM Supercomputing Conference 2007 (SC2007). 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A., Grass N. Seq-gen: an application for the monte carlo simulation of dna sequence evolution along phylogenetic trees. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997;13:235. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. Proceedings of IPDPS2006, HICOMB Workshop, Proceedings on CD. Rhodos, Greece: 2006. Phylogenetic models of rate heterogeneity: a high performance computing perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. Phylogenetic search algorithms for maximum likelihood. In: Elloumi M., Zomaya Albert Y., editors. Algorithms in Computational Molecular Biology: Techniques, Approaches and Applications. Wiley; 2011. pp. 547–577. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A., Ott M. Proceedings of International Conference on Parallel Processing (ICPP'09). IEEE; 2009. Load balance in the phylogenetic likelihood Kernel; pp. 348–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Stamatakis A. The multi-processor scheduling problem in phylogenetics. Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies; 2012. Technical report. [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl D. PhD Thesis. University of Texas at Austin; 2006. Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. [Google Scholar]