Abstract

Objective

Sexual transmission of HIV is the most common route of HIV transmission throughout the world. To prevent sexually transmitted HIV infection, a vaccine is urgently needed. A previous report demonstrated the targeted immunization of the iliac lymph nodes with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) subunits protects rhesus macaques from rectal challenge with SIV. We sought to determine whether this immunization strategy could protect rhesus macaques from vaginal challenge with SIV.

Design

Macaques were immunized with either whole-killed SIV or envelope and core subunit antigen vaccines. Using three independent groups, with three macaques in each group, macaques were immunized by the targeted iliac lymph-node (TILN) route, injecting the vaccine close to the iliac lymph nodes that drain the genital tract.

Results

The TILN immunization procedure induced high-titer SIV-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies in serum in all animals and anti-SIV IgG and IgA antibodies in the cervicovaginal secretions of most animals. After a series of three or four TILN immunizations, the animals were intravaginally challenged with SIVmac251. All animals became virus isolation-positive, except one animal immunized with SIV p27 and gp120. This animal was virus isolation-negative but SIV DNA proviral sequences were detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Conclusions

In this series of studies, reliable protection from vaginal transmission of SIV was not achieved by the TILN immunization procedure.

Keywords: Targeted iliac lymph node, simian immunodeficiency virus, intravaginal challenge, rhesus macaques, vaginal immunity

Introduction

The development of a safe and effective vaccine against HIV infection is a global public health priority. Epidemiological data suggest that more than 75% of HIV infections world-wide are acquired through heterosexual intercourse [1]. Because parenterally administered, attenuated and killed vaccines have not been shown to prevent vaginal simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) transmission [2], efforts to elicit local immunity by using different routes of immunization have intensified. Numerous investigators have reported the presence of anti-HIV and SIV antibodies in the genital tract secretions of infected women [3–5] and female rhesus macaques [6]. In addition, antiviral cytotoxic T lymphocytes have been demonstrated in the cervico-vaginal mucosa of SIV-infected monkeys [7] and HIV-infected women [8]. These findings demonstrate that the full range of HIV/SIV-specific immune responses can be found in the female genital tract.

Live-attenuated SIV administered intravenously can protect macaques from intravenous challenge with pathogenic SIV [9]. However, studies to date in animals and humans have not identified the correlates of immune protection [10]. Intravaginal immunization with an attenuated simian–human chimeric immuno-deficiency virus protects rhesus macaques from intravaginal challenge with pathogenic SIV [11]. Because protective rectal mucosal immunity in macaques is elicited by a targeted iliac lymph-node (TILN) immunization with a subunit SIV envelope and core vaccine [12], we sought to determine whether TILN immunization strategy with whole inactivated SIV or SIV subunits could protect animals from vaginal challenge with SIVmac251.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animals used in this study were captive-bred, multi-parous, cycling female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) from the California Regional Primate Research Center. Prior to their initial use, the animals were negative for antibodies to HIV-2, SIV, type D retrovirus, and simian T-cell leukemia virus type 1. The animals were housed in accordance with American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards. When necessary, the animals were immobilized with 10 mg/kg ketamine HCl (Parke-Davis, Morris Plains, New Jersey, USA), which was injected intramuscularly.

Immunogens and route of immunization

The whole inactivated SIV vaccine consisted of sucrose gradient-purified SIVmac251 that was inactivated with β-propiolactone, as described previously [13]. The origin of the recombinant SIVmac251 gp120 and recombinant SIV p27 has been previously described [14]. SIVmac251 Pr55 and SIVmac239 gp130 were obtained from Quality Biological, Inc. (Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA), and were produced under contract no. N01-AI-05084 of the Vaccine Research and Development Branch (Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). For all immunizations, an aqueous solution of aluminum hydroxide (Imject Alum, Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA) was used as the adjuvant.

All immunizations were performed using the TILN procedure [12]. Briefly, TILN immunization was performed by subcutaneous injection. The needle was first inserted to a depth of 1–2 cm medially to the femoral pulse just above the inguinal ligament, dispensing about 0.15 ml. The needle was then directed at a depth of 4 cm upwards and laterally toward the pelvic floor where the rest of the vaccine (about 0.35 ml) was injected after the needle tip was in the posterior wall of the pelvis. This procedure was performed bilaterally each time. Because this technique involved blind placement of the needle into the posterior wall of the pelvic cavity and the internal anatomy of each animal was variable, it was impossible to be certain that the antigen was identically placed at each immunization. It is important to note that the lymphatic drainage of the posterior wall of the pelvis is directed to the iliac lymph nodes [15].

Immunization protocols

The experiment included five groups of animals (Table 1). The initial study included three groups: two vaccine groups (A and B), and one naive control group (C). Subsequently, two groups [one vaccine group (D) and one control group (E)] were added to the experiment. In group A, three monkeys (22575, 24331 and 25428) were immunized with inactivated whole SIV (200 µg). In group B, three monkeys (21747, 24428 and 24816) were immunized with SIV gp120 (200 µg) and p27 (200 µg). Animals in groups A and B were immunized at 0, 4 and 8 weeks. Intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251 was performed at 10 weeks. Serum samples, cervicovaginal secretions (CVS) and rectal secretions were collected at multiple timepoints. In group C, four macaques (25255, 25422, 24803 and 25597) were used as naive controls and were intravaginally challenged with SIVmac251 at the same time as groups A and B.

Table 1.

Virus isolation from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of targeted iliac lymph-node (TILN)-immunized and control rhesus macaques after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251.

| Challenge timepoint (week) |

Week post-challenge | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macaques | Vaccine | No. vaccinations |

1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 28 | % Positive* |

|

| Group A | ||||||||||||||

| 22575 | Whole SIV | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100 |

| 24331† | Whole SIV | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100 | |||

| 25428 | Whole SIV | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100 |

| Group B | ||||||||||||||

| 21747 | p27 + gp120 | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100 |

| 24816 | p27 + gp120 | 3 | 10 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 |

| 24428† | p27 + gp120 | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100 | ||

| Group C | ||||||||||||||

| 25255 | None | 0 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100 | ||

| 25422 | None | 0 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 100 | ||

| 24803 | None | 0 | 10 | + | +§ | 100 | ||||||||

| 25597 | None | 0 | 10 | + | +§ | 100 | ||||||||

| Group D | ||||||||||||||

| 20634† | Pr55 + gp130 | 4 | 17 | + | + | − | ND | + | + | 80 | ||||

| 22212† | Pr55 + gp130 | 4 | 17 | − | + | + | ND | + | + | 80 | ||||

| 22590 | Pr55 + gp130 | 4 | 17 | − | + | + | ND | + | + | 80 | ||||

| Group E | ||||||||||||||

| 26665 ‡ | None | 0 | 17 | + | − | − | ND | − | − | 20 | ||||

| 26742 | None | 0 | 17 | − | − | + | ND | + | + | 60 | ||||

Of the PBMC cocultures that were performed, this is the percentage from which simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) was isolated.

Animals were sacrificed at 19 weeks (24331, group A), 23 weeks (24428, group B), 35 weeks (20634, group D), 41 weeks (22212, group D) and 34 weeks (26665, group E). At necropsy, PBMC and mononuclear cell suspensions obtained from spleen, inguinal, iliac and axillary lymph nodes were cocultivated with CEM-X174 cells as described for PBMC in Material and methods. All these cultures for all animals were virus isolation-positive, except control animal (26665). PBMC and mononuclear cells suspensions obtained from spleen and lymph nodes of this animal (26665) were virus isolation-negative.

In addition to the standard PBMC coculture technique described in Materials and methods, CD8+ T cells were depleted from the PBMC of this animal (26665) at weeks 9 and 12 by using immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Inc., Lake Success, New York, USA). The CD8+ T-cell-depleted PBMC were cocultured with CEM-X174 cells. Both CD8+-depleted cultures were virus isolation-negative.

Animals were killed at this time for experimental reasons unrelated to this study. None, No immunization; ND, not done.

In group D, three monkeys (20634, 22212 and 22590) were immunized with subunit recombinant SIVmac251 Pr55gag (200 µg) and SIVmac239 gp130 (200 µg) at 0, 5, 8 and 14 weeks. Intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251 was performed at 17 weeks. This choice of antigen was dictated by the limited availability of the SIV subunit antigens used in group B. Serum samples and CVS were collected at multiple timepoints. Group E comprised two naive monkeys (26665, 26742) that served as controls and were intravaginally challenged with SIVmac251 at the same time as group D.

Sample collection

Peripheral blood was collected by venipuncture into heparinized tubes (for cell isolation) or into non-heparinized tubes (for serum). Vaginal washes consisted of a mixture of cervical and vaginal secretions and were collected by vigorously infusing 6 ml sterile phosphate-buffered saline into the vaginal canal and aspirating as much of the instilled volume as possible. Care was taken to insure that the cervical mucus was bathed in the lavage fluid and that no trauma to the mucosa occurred during the procedure. The samples were snap-frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until analysis. For analysis, the samples were thawed, centrifuged at 5000 r.p.m. in a microcentrifuge for 10 min and the supernatant was collected. Neomycin sulfate (200 µg/ml; ICN Biomedical, Inc., Aurora, Ohio, USA) and a cocktail (10% vol/vol) of protease inhibitors [0.6 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride, 3 µg/ml aprotinin, 30 µM leupeptin, 9.75 µM bestatin; Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, Missouri, USA] was added to the supernatant and the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed as described below. It was estimated that the sample collection and preparation procedure resulted in at least a 10-fold dilution of the CVS. Rectal washings were collected without trauma, with the aid of flexible, lubricated pediatric nasogastric tubes and processed in the same manner as the CVS samples.

Antibody ELISA assays

Prior to determining antibody titers, sera and vaginal secretions were screened for the presence of anti-SIV antibodies using a 1 : 100 dilution of sera and a 1 : 4 dilution of vaginal washes or rectal washes in the same ELISA assay protocol used to determine antibody titers, described below. Results of the screening assay were calculated using the following ratio: change in optical density (ΔOD)/cut-off (CO), where ΔOD is defined as the difference between the mean OD of a dilution of sample tested in two antigen-coated wells and the mean OD of the same dilution of sample tested in two antigen- free (control) wells. The cut-off (CO) value is the mean ΔOD + 3 SD of duplicate wells containing sera or vaginal washes from 12 randomly selected seronegative adult female rhesus macaques. If the ΔOD/CO ratio for a sample was greater than 2.0, the sample was considered to be positive.

An additional analysis was used to determine anti-SIV antibody titers in antibody positive serum, CVS, and rectal washes. Ninety-six-well microtiter plates (Nunc Immunoplate II Maxisorp, Applied Scientific, South San Francisco, California, USA) were coated with whole pelleted SIVmac251 (Advanced Biologics, Inc., Columbia, Maryland, USA) at 5 µg/ml in 0.1 M Na2CO3/NaHCO3 buffer (pH 9.6) and blocked with 4% non-fat powdered milk. Plasma and vaginal wash samples were serially diluted (1 : 4) in duplicate and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. The initial dilution of serum was 1 : 10 000 for SIV-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G assay and 1 : 1000 for SIV-specific IgA assay. Antibody binding was detected using a 1 : 2000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-monkey IgG(Fc) (100 µl per well) or 1 : 1000 peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-monkey IgA(Fc) (100 µl per well; Nordic Laboratories, San Juan Capistrano, California, USA) for 1 h at 37°C. Plates were developed with o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 5 min and stopped with H2SO4 before reading the OD at 490 nm. For each serum or vaginal/rectal wash sample, the endpoint titer of anti-SIV antibodies was defined as the reciprocal of the last dilution giving a ΔOD value greater than 0.2, where ΔOD was defined as the difference between the mean OD of two antigen-coated and two antigen-free (control) wells.

Virus isolation

Virus was isolated from heparinized whole blood obtained from the SIV-inoculated rhesus macaques. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll gradient separation medium (Lymphocyte Separation Medium, Organon Teknika, West Chester, Pennsylvania, USA) and cocultured with CEM-X174 cells as previously described [11]. Five million PBMC were cocultivated with 2–3 million CEM-X174 cells. Aliquots of the culture media were assayed regularly for the presence of SIV major core protein (p27) by an antigen capture ELISA [16]. Cultures were considered positive if they were antigen-positive at two consecutive timepoints. A detailed description of the technique and criteria to determine whether culture media was antigen-positive has been previously published [17]. All cultures were maintained for 8 weeks before being scored virus-negative. Blood samples for virus isolation were collected at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 and 28 weeks post-challenge.

Polymerase chain reaction-based detection of SIV proviral DNA sequences

The sequences of the nested primer pairs used to detect SIV gag have been previously described [11]. Nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out on genomic PBMC DNA in a DNA Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Emeryville, California, USA) using a modification of a previously described technique [18]. Briefly, cryopreserved PBMC isolated from whole blood were washed three times in Tris buffer at 4°C and resuspended at 107 cells/ml. Ten microliters of the cell suspension were added to 10 µl PCR lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 0.45% Nonidet P-40, 0.45% Tween-20) with 200 µg/ml proteinase K. The cells were incubated for 3 h at 55°C, followed by 10 min at 96°C. Two rounds of 30 cycles of amplification were performed on aliquots of plasmid DNA containing the complete genome of SIVmac1A11 (positive control) or aliquots of cell lysates using conditions described elsewhere [18]. DNA from uninfected CEM-X174 cells was amplified as a negative control in all assays to monitor potential reagent contamination. Using the primers listed previously [11], β-actin DNA sequences were amplified with two rounds of PCR (30 cycles per round) from all PBMC lysates to detect potential inhibitors of Taq polymerase in cell lysates. Following the second round of amplification, a 10 µl aliquot of the reaction product was removed and run on a 1.5% agarose gel. Amplified products in the gel were visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Blood samples for PCR analysis were collected at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 weeks post-challenge.

Branched DNA quantification of plasma SIV RNA

Quantitative assays for the measurement of SIV RNA were performed using a branched DNA signal amplification assay specific for SIV [19]. This assay is similar to the Quantiplex HIV RNA assay [20] except that target probes were designed to hybridize with the pol region of the SIVmac group of strains including SIVmac251. SIV pol RNA in plasma samples were quantified by comparison with a standard curve produced using serial dilutions of cell-free SIV-infected tissue culture supernatant. The quantification of this standard curve was determined by comparison with purified, quantified, in vitro-transcribed SIVmac239 pol RNA. SIV RNA associated with viral particles was measured after being pelleted from 1 ml heparinized plasma (23 500 g for 1 h at 4°C). The lower quantification limit of this assay was 10 000 copies of SIV RNA per ml plasma.

Results

Anti-SIV immune responses at the time of challenge

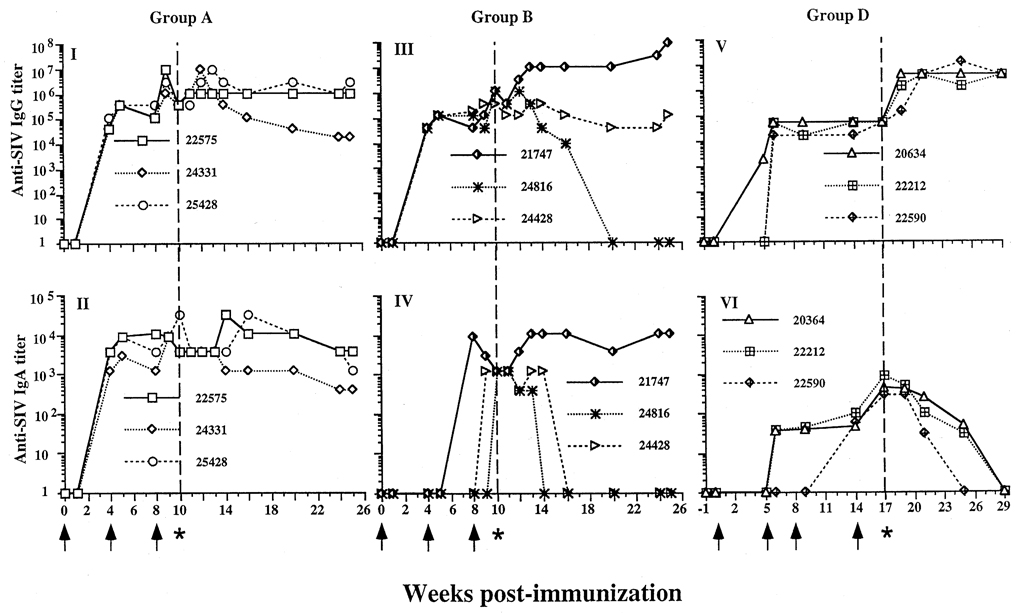

In groups A, B and D, a total of nine animals were TILN-immunized with either whole inactivated SIV or SIV subunit antigens (Table 1). All immunized macaques, irrespective of the vaccine, developed serum IgG and IgA antibodies to SIVmac251 by the third immunization (Fig. 1). Most animals had high titers of IgG-specific antibodies in serum within 4 weeks of the first TILN immunization. After the second immunization (week 4), most animals had consistently high titers of anti-SIV IgG antibodies which remained high after the third immunization (Fig. 1). The peak titers of IgG antibodies in serum ranged from 105 to 107. These were the highest IgG antibody titers achieved with any immunization procedure of rhesus macaques in our laboratory. All immunized animals developed serum IgA antibody responses by the last immunization. The IgA antibody titers were also high ranging from 102 to 105.

Fig. 1.

Serum anti-simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgA titers in targeted iliac lymph-node (TILN)-immunized rhesus macaques before and after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251. (I and II) Group A, three macaques were immunized with whole inactivated SIV at weeks 0, 4 and 8 (↑), and challenged at week 10 (indicated by asterisk and dashed vertical line). Serum IgG (I) and IgA titers (II) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. All animals had high anti-SIV IgG and IgA antibody titers at 4 weeks post-immunization. The third immunization enhanced both IgG and IgA antibody responses. (III and IV) Group B, three macaques immunized with SIV subunits p27 and gp120. (III) Anti-SIV IgG titers were high at challenge and remained high after challenge, except one animal (24816) did not maintain high titers post-challenge. This animal was virus isolation-negative. (IV) All animals had an anti-SIV IgA response at challenge. The IgA response in two animals (24816 and 24428) declined at 4–6 weeks. (V and VI) Group D, three animals immunized with Pr55 and gp130 at weeks 0, 5, 9 and 14, and challenged at week 17. (V) The anti-SIV IgG response had the same pattern as group A. (VI) All animals had an IgA response at challenge, but after challenge, the anti-SIV IgA response was transient.

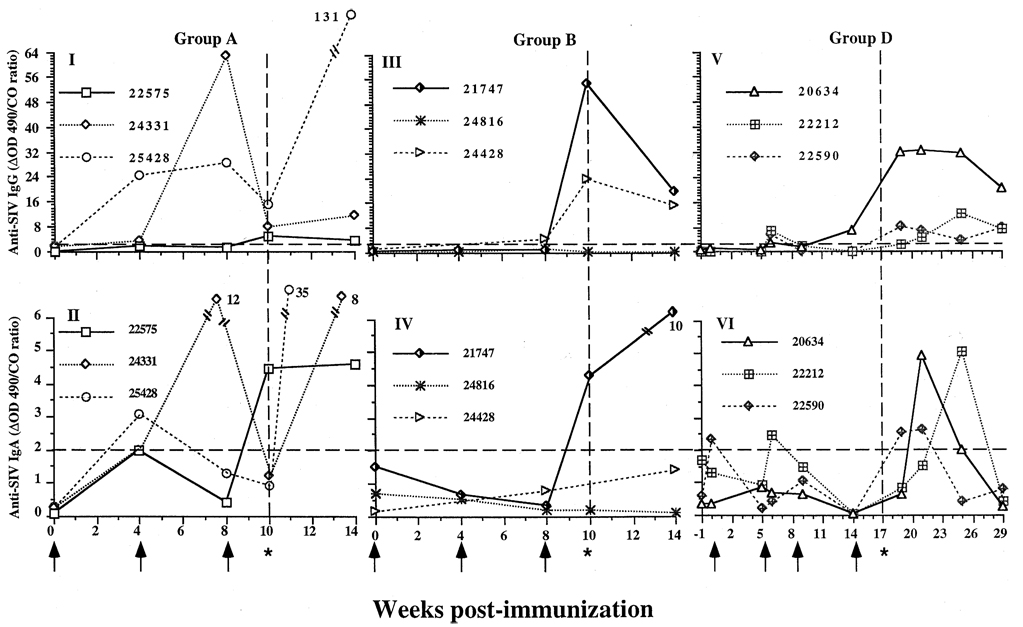

All immunized macaques, irrespective of vaccine preparation, had detectable SIV-specific antibodies in CVS after the last TILN immunization, except animal 24816, which had neither SIV-specific IgG nor IgA antibodies in CVS (Fig. 2). On the day of challenge, the positive ΔOD/CO ratios of SIV-specific IgG antibody ranged from 4 to 16 in group A, from 24 to 56 in group B, and from 4 to 24 in group D. Titration of SIV-specific IgG in CVS samples was only performed for the animals in group D. Titers of SIV-specific IgG antibodies in CVS samples ranged from 4 to 4000 (data not shown) and corresponded to the relative ΔOD/CO ratio values for the samples. Prior to challenge, SIV-specific IgA antibodies were detected in the vaginal secretions of six out of nine animals immunized by the TILN route. With exception of one animal in group A (24331), the ΔOD/CO ratios of SIV-specific IgA antibody were low (2.0–4.0). On the day of challenge, the mean total IgG concentrations in CVS of the nine immunized animals was 9.1 µg/ml (SEM, 4.2 µg/ml), in comparison with the mean total IgA in CVS, which was 13.4 µg/ml (SEM, 3.3).

Fig. 2.

Anti-simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) antibody levels in cervicovaginal secretions (CVS) of targeted iliac lymphnode-immunized rhesus macaques before and after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251. (I and II) Group A, whole SIV-immunized animals (22575, 24331, 25428) had (I) immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies to SIV, and (II) detectable anti-SIV IgA in vaginal secretions at some point prior to challenge. One animal (22575) had IgA antibodies to SIV in CVS at the time of challenge (indicated by asterisk and dashed vertical line). After challenge, all the animals had anti-SIV IgG and IgA antibodies in CVS. (III and IV) Group B, p27 and gp120 immunized animals, (III) two animals (21747 and 24428) had IgG antibodies to SIV and (IV) one animal (21747) had IgA antibodies to SIV at time of the challenge. All these animals were anti-SIV IgG and IgA antibody-positive at 4 weeks post-challenge. (V and VI) Group D, Pr55 and gp130 immunized animals (20634, 22212, 22590), (V) all animals had anti-SIV IgG in vaginal secretions before challenge, and (VI) two animals (22590 and 22212) had anti-SIV IgA antibodies to SIV in CVS before challenge. After challenge, anti-SIV IgG and IgA were detected in the CVS of all animals. Anti-SIV IgA had a transient pattern but was detectable at least one timepoint after challenge. The displayed numerical value is the ratio of the difference in optical density (ΔOD) of the sample to the cut-off value (see Materials and methods for explanation). A ΔOD/CO ratio of < 2 was considered negative (indicated by horizontal dashed line). It was estimated that the sample collection technique resulted in at least a 100-fold dilution of the secretions.

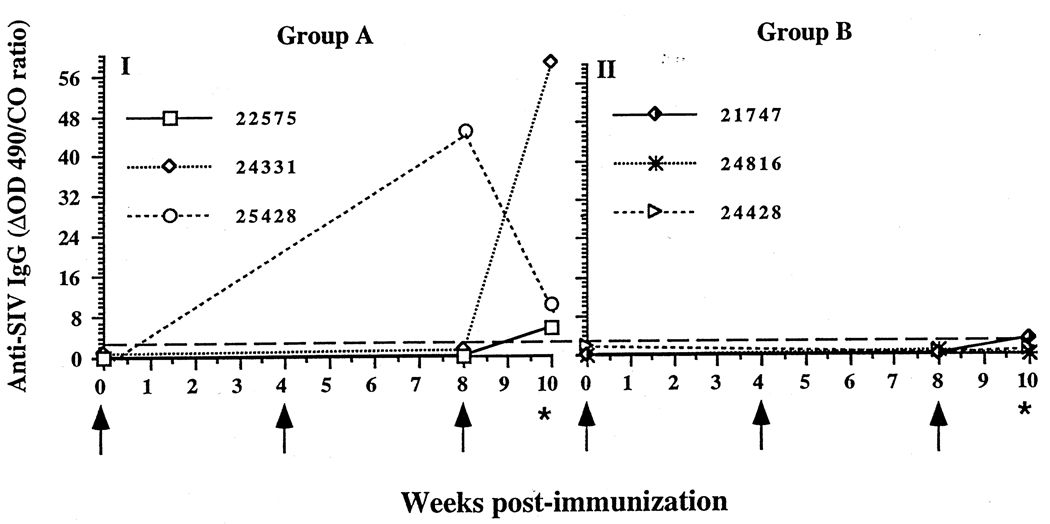

Anti-SIV IgG antibody in rectal washes was present in group A animals after the last boost. In group B, anti-SIV IgG was detected in rectal washes of one animal at one timepoint. No IgA anti-SIV antibody was detected in either group A or B (Fig. 3). Anti-SIV antibodies in the rectal washes from group D animals were not assessed.

Fig. 3.

Anti-simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) antibody levels in rectal secretions of targeted iliac lymph-node-immunized rhesus macaques before intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251. (I) Three animals (22575, 24331, 25428) immunized with inactivated whole SIV had anti-SIV immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies in rectal secretions at the time of the intravaginal challenge. (II) Three animals (21747, 24816, 24428) immunized with p27 and gp120 had low or undetectable anti-SIV IgG in rectal secretions. No anti-SIV IgA was detectable in rectal secretions of any animal.

Virus isolation after intravaginal challenge

The challenge inoculum consisted of 1 ml SIVmac251 propagated in rhesus macaque PBMC (105 median tissue culture infective doses) delivered via a tuberculin syringe into the vaginal canal. Two doses of the virus inoculum were given to each animal with a 4 h interval between the inoculations. After challenge, virus isolation was performed at timepoints indicated in Table 1. All control animals became virus isolation-positive, although one animal (26665) was virus isolation-positive at only one timepoint (Table 1). All immunized animals, except for 24816 in group B, became virus isolation-positive. Animals 24331 in group A, 24428 in group B, and 20634 and 22212 in group D were killed at the times noted in Table 1. At necropsy, mononuclear cells obtained from the spleen, inguinal, iliac and axillary lymph nodes of these animals were virus isolation-positive. We found that one macaque (24816, group B) remained virus isolation-negative after challenge. However, SIV gag DNA was detected in PBMC from this animal (Table 2). Thus, TILN immunization did not reliably protect rhesus macaques from intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251.

Table 2.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based detection of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gag DNA sequences in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of targeted iliac lymph-node (TILN)-immunized and control rhesus macaques after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251.

| Challenge timepoint (week) |

Week post-challenge | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macaques | Vaccine | No. vaccinations |

1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | |

| Group A | ||||||||||

| 22575 | Whole SIV | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 24331 | Whole SIV | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 25428 | Whole SIV | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Group B | ||||||||||

| 21747 | p27 + gp120 | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 24816 | p27 + gp120 | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 24428 | p27 + gp120 | 3 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Group C | ||||||||||

| 25255 | None | 0 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 25422 | None | 0 | 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 24803 | None | 0 | 10 | + | +* | |||||

| 25597 | None | 0 | 10 | + | +* | |||||

| Group D | ||||||||||

| 20634 | Pr55 + gp130 | 4 | 17 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 22212 | Pr55 + gp130 | 4 | 17 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 22590 | Pr55 + gp130 | 4 | 17 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Group E | ||||||||||

| 26665 | None | 0 | 17 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 26742 | None | 0 | 17 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

Animals were killed at this time for experimental reasons unrelated to this study.

PCR-based detection of SIV gag DNA from PBMC

PCR amplification of proviral DNA from PBMC was performed at the timepoints indicated in Table 2. After SIVmac251 challenge, SIV gag DNA was detected in the PBMC of all immunized animals at all timepoints tested. One control animal (26665) was PBMC proviral DNA-positive at only two timepoints (Table 2). The result of proviral SIV gag detection was consistent with the virus isolation results in all animals except 24816. Animal 24816 was virus isolation-negative but PBMC SIV gag DNA-positive. Apparently, the CD4+ cells from this animal (24816) had integrated proviral DNA but there was no detectable infectious virus in PBMC. This may have been due to the presence of defective SIV provirus in the PBMC or effective suppression of virus replication.

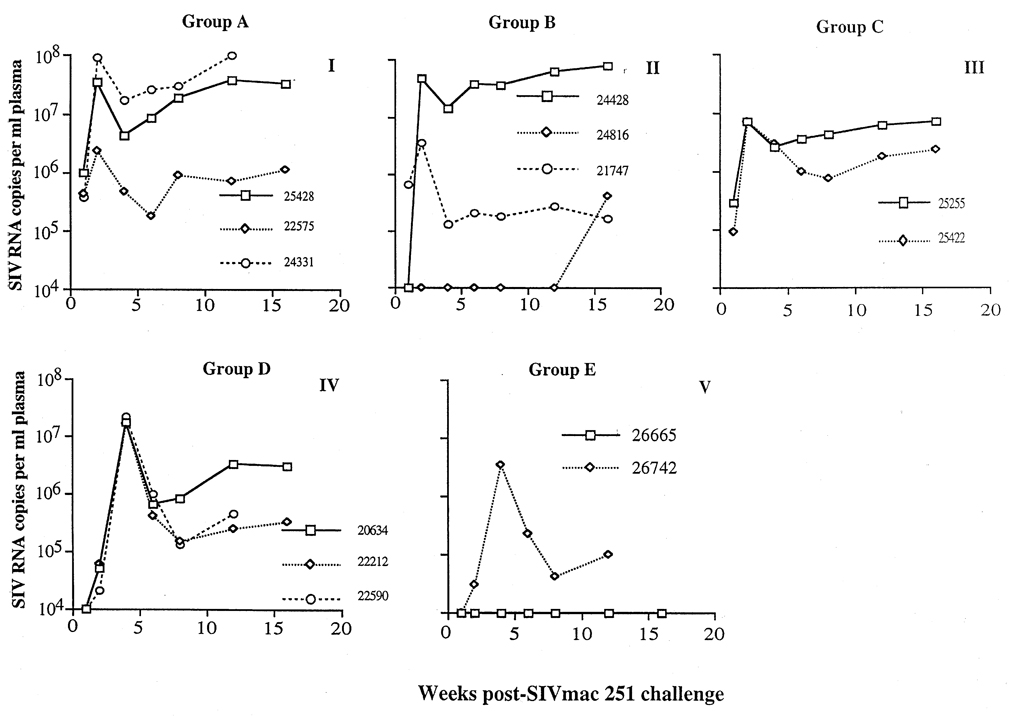

Branched DNA quantification of plasma SIV RNA

Plasma SIV pol RNA was quantified by the branched DNA assay from the day of challenge until 17 weeks post-challenge (Fig. 4). In the naive control animals (group C and E), except animal 26665, a distinct peak of plasma SIV pol RNA was observed within 4 weeks after vaginal challenge. Peak levels of approximately 107 viral RNA copies/ml of plasma were observed in these samples. Five weeks post vaginal challenge, plasma viral RNA was detected in plasma at high levels (from 106 to 108 copies/ml plasma, in 25428, 24331 and 24428), or at intermediate levels (from 104 to 106 copies/ml plasma, in 22575, 21747, and group D animals). SIV RNA was below the level of detection (< 10 000 RNA copies/ml plasma) for one animal 26665 in group E. The virus isolation negative animal (24816 in group B) had intermediate plasma RNA levels at one timepoint (16 weeks post intravaginal challenge). There was no obvious difference in the plasma RNA levels between naive control and TILN-immunized animals. Thus, it does not appear that the immune responses induced by the TILN immunizations decreased SIV replication.

Fig. 4.

Viral RNA levels in plasma of targeted iliac lymph-node-immunized rhesus macaques after intravaginal challenge with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)mac251. Plasma viral RNA levels were determined by branched DNA assay. (I) Animals immunized with whole inactivated SIV. (II) Animals immunized with p27 and gp120; note that animal 24816 was virus isolation-negative and viral RNA-negative in plasma until week 16 post-challenge. (IV) Animals immunized with Pr55 and gp130. (III and V) Non-immunized control animals. There were no obvious differences in plasma viral RNA levels in the immunized and control animals.

Anti-SIV immune responses after intravaginal SIVmac251 challenge

All immunized animals in group A , B and D with the exception 24816 in group B maintained high sera IgG antibody titers for more than 15 weeks post-challenge. This antibody pattern is characteristic of an ongoing immune response. It should be noted that serum anti-SIV IgG progressively declined to negative levels in animal 24816 (Fig. 1). This animal was virus isolation-negative (Table 1), and this antibody response pattern was consistent with lack of a productive virus infection. Serum anti-SIV IgA antibody in group A and animal 21747 in group B were also maintained at high levels after intravaginal SIVmac251 challenge. However, two animals (24816 and 24428) in group B and animals in group D had a transient pattern of serum IgA antibody, and serum IgA antibodies declined to undetectable levels at 4–8 weeks post-challenge (Fig. 1).

All immunized animals in groups A, B and D, except 24816 and 24428 (group B), had anti-SIV IgG and IgA antibodies in CVS at one or two timepoints post-challenge. Animal 24816 had no detectable anti-SIV IgG or IgA antibody in CVS after intravaginal challenge (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Eight out of nine rhesus macaques immunized with a variety of SIV antigens by the TILN route became virus isolation-positive after vaginal challenge with pathogenic SIVmac251. Rhesus macaques immunized by the TILN route had very high IgG and IgA-specific antibody titers in serum (105 to 107 for IgG; 102 to 105 for IgA), although serum IgG antibody levels were considerably higher than IgA levels. Prior to SIV challenge, eight out of nine animals in this study had anti-SIV-specific IgG in vaginal secretions and six out of nine animals had anti-SIV IgA in vaginal secretions. After challenge, one animal (24816) remained virus isolation-negative, but was consistently SIV gag DNA-positive and was plasma SIV RNA-positive at one timepoint. We do not know whether the inability to isolate virus in this animal was due to the immune responses induced by the immunization procedures, although prior to challenge this animal did not have detectable anti-SIV IgG or IgA in vaginal secretions. In this experiment, TILN immunization did not reliably protect rhesus macaques from intravaginal challenge with SIVmac251. The emphasis in AIDS vaccine development has shifted from eliciting sterilizing immunity to inducing immune responses that can reduce post-challenge viral load and delay progression to clinical disease, and this has been achieved in the SIV/macaque model [21]. With one exception (animal 24816), there was no evidence that animals immunized by TILN route in this study had decreased virus load after vaginal challenge.

An analysis of the patterns of cytokine secretion by the CD4+ T cells of the immunized animals in group A and B has been published as a separate report [22], but the results will be briefly summarized here. Following the second immunization, CD4+ T cells from all the animals had a T-helper (TH)-1 pattern of cytokine secretion [interferon (IFN)-γ > interleukin (IL)-4] after PBMC were pulsed with SIV antigens in vitro. After the third immunization, the antigen-specific cytokine pattern shifted to a TH2 pattern (IL-4 > IFN-γ) in five out of six animals. One animal (24816) maintained a TH1 cytokine profile at the time of challenge. This animal had no anti-SIV antibodies in secretions but did have significant anti-SIV IgG titers in serum. Significantly, this animal remained virus isolation-negative after vaginal challenge with SIVmac251 and may thus have been able to effectively suppress virus replication. The result in this animal provides support for the idea that TH1 immune responses are desirable for HIV-1 vaccines.

It has been shown that TILN immunization with a subunit SIV envelope and core vaccine protected rhesus macaques from intrarectal challenge with SIVmac32HJ5 molecular clone [12]. Four out of seven macaques were protected from infection. The remaining three macaques had either a decrease in viral load or transient viremia [12]. The difference in the results of the vaginal and rectal challenge studies may be related to differences in (i) the virulence of the challenge virus, (ii) antiviral immunity at the rectal and vaginal mucosal surfaces, and (iii) virus transmission and dissemination at the two mucosal surfaces. SIVmac251 used in vaginal challenge is more virulent in rhesus macaques than the SIVmac32HJ5 clone. In a study comparing the two viruses directly, it was shown that animals infected with SIVmac32HJ5 were less likely to develop AIDS than animals infected with SIVmac251 [23].

Induction of effective humoral and cellular antiviral immune response is likely to be essential for a vaccine against sexually transmitted HIV. Furthermore, vaccine-induced production of non-specific antiviral effector molecules such as chemokines, IFN or other antiviral factors may be important for protection against HIV. Antibodies present in local secretions and specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in mucosal tissues comprise the first line of immune defense to prevent viral dissemination and subsequent systemic infection. A successful vaccine must provide excellent protective immunity in the local mucosa to prevent subsequent systemic infection. The route of administration of immunogens to induce protective anti-SIV/HIV mucosal immunity is an important issue. Our results indicate that immunization by the TILN route failed to reliably protect macaques from vaginal challenge with SIVmac251. In our experiment, one macaque (24816) was virus isolation-negative and SIV gag DNA-positive after intravaginal SIVmac251 challenge, and this animal maintained a TH1 CD4+ T-cell response to the immunization protocol. We have previously shown that it is possible to protect rhesus macaques from vaginal challenge with SIV by immunizing the genital tract with a live attenuated virus [11]. We believe that protection from HIV sexual transmission may be possible by using immunization strategies that simulate the immune responses elicited by attenuated virus infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P. Brosio and S. Joye for technical assistance.

Sponsorship: This study was supported by US Public Health Service grants AI35545, AI 35544, AI 35932 and RR00169.

References

- 1.Over M, Piot P. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases in developing counties: public health importance and priorities for resource allocation. J Infect Dis. 1996;174 suppl 2:S162–S175. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_2.s162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marthas M, Sutjipto S, Miller C, et al. Efficacy of live-attenuated and whole-inactivated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines against intravenous and intravaginal challenge. In: Brown F, Chanock RM, Ginsberg HS, Lerner RA, editors. Vaccines 1992. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press ; 1992. pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archibald DW, Witt DJ, Craven DE, Vogt MW, Hirsch MS, Essex M. Antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus in cervical secretions from women at risk for AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:240–241. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu X, Belec L, Martin PMV, Pillot J. Enhanced local immunity in vaginal secretion of HIV-infected women. Lancet. 1991;338:323–324. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90470-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu XS, Belec L, Pillot J. Anti-gp160 IgG and IgA antibodies associated with a large increase in total IgG in cervicovaginal secretions from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected women. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1189–1192. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller C, Kang D, Marthas M, et al. Genital secretory immune response to chronic SIV infection: a comparison between intravenously and genitally inoculated rhesus macaques. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;88:520–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohman BL, Miller CJ, McChesney MB. Antiviral cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the vaginal mucosa of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 1995;155:5855–5860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musey L, Hu Y, Eckert L, Christensen M, Karchmer T, McElrath MJ. HIV-1 induces cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the cervix of infected women. J Exp Med. 1997;185:293–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniel MD, Kirchhoff F, Czajak SC, Sehagal PB, Desrosiers RC. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science. 1992;258:1938–1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1470917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston MI. Progress in AIDS vaccine development. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;108:313–317. doi: 10.1159/000237173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller CJ, McChesney MB, Lü XS, et al. Rhesus macaques previously-infected with SHIV are protected from vaginal challenge with pathogenic SIVmac239. J Virol. 1997;71:1911–1921. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1911-1921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehner T, Wang Y, Cranage M, et al. Protective mucosal immunity elicited by targeted iliac lymph node immunization with a subunity SIV envelope and core vaccine in macaques. Nature Med. 1996;2:767–775. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson JR, McGraw TP, Keddie E, et al. Vaccine protection of rhesus macaques against simian immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1990;6:1239–1246. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehner T, Bergmeier L, Tao L, et al. Mucosal receptors and T-and B-cell immunity. In: Giraldo G, Bolognesi DP, Salvatore M, Beth-Giraldo E, editors. Development and Applications of Vaccines and Gene Therapy in AIDS. Basel: Karger; 1996. pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams PL, Warwick R. Lymphatic drainage of the female reproductive organs. In: Williams PL, Warwick R, editors. Gray’s Anatomy. 36th British Edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1980. p. 798. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohman B, Higgins J, Marthas M, Marx P, Pedersen N. Development of simian immunodeficiency virus isolation, titration, and neutralization assays which use whole blood from rhesus monkeys and an antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2187–2192. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2187-2192.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marthas ML, Ramos RA, Lohman BL, et al. Viral determinants of simian immunodeficiency (SIV) virulence in rhesus macaques assessed by using attenuated and pathogenic molecular clones of SIVmac. J Virol. 1993;67:6047–6055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6047-6055.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unger RE, Marthas ML, Lackner AA, et al. Detection of simian immunodeficiency virus DNA in macrophages from infected rhesus macaques. J Med Primatol. 1992;21:74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dailey PJ, Zamroud M, Kelso R, Kolberg J, Urdea M. Quantitation of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) RNA in plasma of acute and chronically infected rhesus macaques using a branched DNA (bDNA) signal amplification assay. 13th Annual Symposium on Nonhuman Primate Models of AIDS. Monterey. 1995 November; abstract 99. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pachl C, Todd JA, Kern DG, et al. Rapid and precise quantification of HIV-1 RNA in plasma using a branched DNA signal amplification assay. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8:446–454. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199504120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirsch VM, Fuerst TR, Sutter G, et al. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J Virol. 1996;70:3741–3752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3741-3752.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawabata S, Miller CJ, Lehner T, et al. Induction of Th2 cytokine expression for p27-specific IgA B cell responses after TLN immunization with SIV antigens in rhesus macaques. J Infect Dis. doi: 10.1086/513811. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashworth LAE, Hall GA, Sharpe SA, et al. Constitutive expression of major histocompatibility complex class II antigens on monocytes and B cells correlates with disease in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1261–1267. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]