Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the in vitro anti-viral effect of honey on varicella zoster virus.

Methods

Manuka and clover honeys were used at concentrations ranging from 0-6% wt/vol. A clinical VZV isolate was obtained from a zoster vesicle and used at low passage. Various concentrations of manuka and clover honey were added to the tissue culture medium of VZV-infected human malignant melanoma (MeWo) cells.

Results

Both types of honey showed antiviral activity against varicella zoster virus with an approximate EC50 = 4.5 % (wt/vol).

Conclusions

Our results showed that honey has significant in vitro anti-VZV activity. As, honey is convenient for skin application, is readily available and inexpensive, honey may be an excellent remedy to treat zoster rash in developing countries where antiviral drugs are expensive or not easily available.

Keywords: Varicella Zoster, Shingles, Zoster, Honey, Antivirals, Translational Medicine

Introduction

Herpes zoster (shingles) is the reactivation of varicella zoster virus from latency in cranial, autonomic and dorsal root ganglia and characterized by rash and severe pain in affected dermatomes. [1] Zoster is a disease affecting more than one million people per year in United States. [2] Zoster is especially common in developing poor countries possibly due to malnutrition, chronic diseases, and ineffective immunization programs. Patients affected by zoster in poor countries are more prone to develop complications such as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), herpes zoster ophthalmicus, vasculitis, meningitis, and myelitis. [3] Antiviral VZV therapeutic agents effective for treating VZV reactivation such as acyclovir, famcyclovir and valacyclovir are very expensive in developing countries and are not readily available. There is great need for a remedy which is inexpensive and easily available in developing countries.

Since antiquity, honey has been used to treat many diseases. [4-8] Currently, honey has been shown to have excellent antibacterial activity for many wound pathogens. [9, 10] Honey has excellent antibacterial activity against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and various species of pseudomonas commonly associated with wound and burn infections. [11-14] Honey dressings are used commonly to manage skin and burn wounds infections. [15] Honeys also possess antifungal activity. [16] Honey has antiviral activity against Rubella virus [17], and honey is used topically to treat recurrent herpes simplex lesions. [18] In this study we screened two types of honey for antiviral activity against a clinical isolate of varicella zoster virus.

Materials & Method

Cell culture

Human malignant melanoma cells (MeWo) were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (DMEM, Life Technologies, Carlsbad CA). The MeWo cell line was established from a skin biopsy of malignant melanoma, and is the standard cell line used to propagate VZV.[19]

Virus stock

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) obtained from a zoster vesicle and shown to be of the European strain was used before the 20th in vitro passage [20] Since VZV is highly cell-associated, virus was propagated by co-cultivation of infected cells with uninfected cells at ratios ranging from 1:4 to 1:100 depending on use. VZV stocks were prepared using infection ratios of 1:100 and dose response experiments were performed at infection ratios of 1:4. [21].

Treatment with honey

Commercially obtained pure clover and Manuka honey were diluted to a final concentration ranging from 0% to 6% (wt/vol) in culture medium and filter sterilized.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability in various honey concentrations was determined by neutral red uptake assay. [22] Briefly, after 3 days in culture MeWo cells were incubated for 3 hrs with 40 ug/ml neutral red (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in DMEM, fixed in 0.5% formaldehyde, 1% CaCl2 for 1 min, dissolved in 50% ethanol, 1% acetic acid for 5 min, and optical density at 560 nm determined on triplicate samples.

Infectivity assay

MeWo cells infected with VZV and uninfected MeWo cells were incubated in culture medium containing various honey concentrations. After plaque development (3 days post-infection) cultures were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized for 10 minutes in methanol/acetone (50:50; v/v) and extensively washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl). VZV plaques were identified by immunostaining. Briefly, monolayers were blocked for 60 minutes in 3% blocked for 60 minutes in 3% BSA in TBS, incubated for 60 minutes with primary antibody (rabbit anti-IE63: 1:1,000 dilution) [23] followed by 60 minutes incubation with alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG; 1:10,000 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Immunostaining was visualized with NBT/BCIP (Pierce, Rockford IL). Between all incubations, the cultures underwent extensive washing in TBS. Plaques were counted with the aid of a dissecting microscope (4 × magnifications).

Results & Discussion

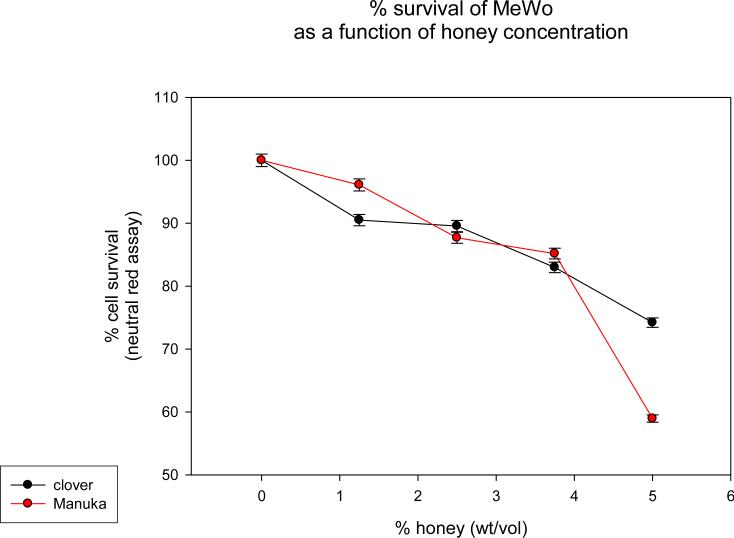

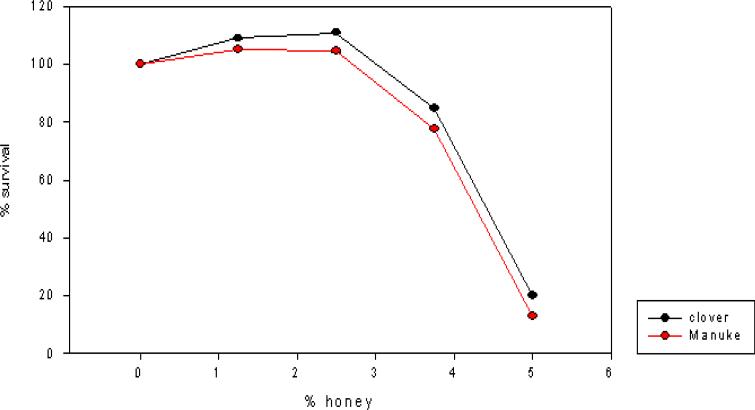

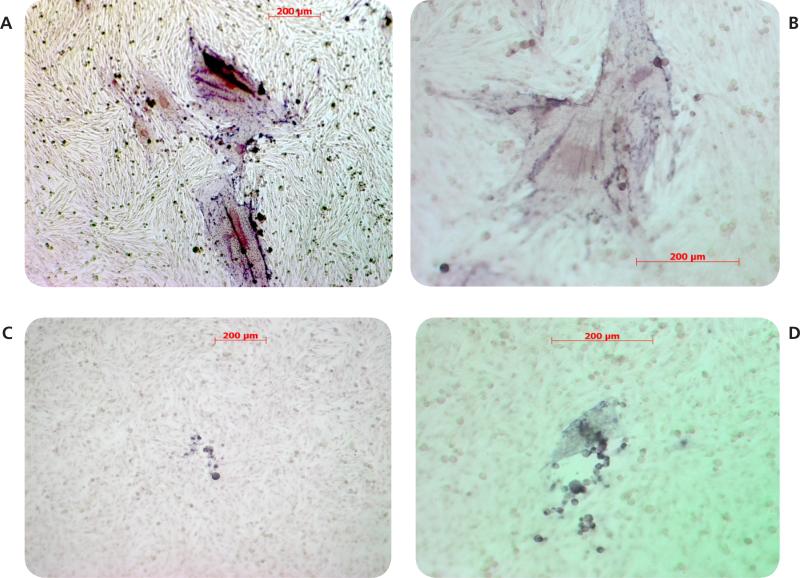

Both clover and Manuka honey are readily soluble in water, and at low concentrations inhibit neutral red uptake to equal amounts. MeWo cells in both honey concentrations ≤ 3.75% showed equal survival slopes (Fig. 1). This is most likely due to nonspecific osmotic actions of the sugars. Both types of honey have concentration dependent in vitro anti-VZV activity with half maximal effective concentration (EC50) approximately 4.5% (wt/vol) (Fig. 2). Manuka honey showed a slightly less EC50 as compared to clover honey. At the EC50 concentration, cells remained viable. Higher honey concentrations resulted in significant reduction in VZV plaque size. (Fig. 3)

Figure 1. Viability of MeWo Cells in dilute honey solutions.

Neutral red uptake assay was used to determine cell viability in various honey concentrations. MeWo cells were incubated for 3 hrs with 40 ug/ml neutral red in DMEM, fixed in 0.5% formaldehyde, 1% CaCl2 for 1 min, dissolved in 50% ethanol, 1% acetic acid for 5 min. Optical density was determined at 560 nm on triplicate samples. Cytotoxicity for both honeys is similar until highest concentration tested. At 5 % dilution, clover honey is more toxic to MeWo cells than Manuka honey.

Figure 2. Anti-VZV activity of manuka and clover honeys.

MeWo cells were infected with VZV and treated with the indicate concentrations of manuka and clover honeys. At 3 days post infection, virus plaques were immunostained and counted.

Figure 3.

Effect of honey on VZV plaque morphology in MeWo cells. MeWo cells were infected with VZV and maintained in 0% (panels A and B) or 6% (panels C and D) honey. Virus plaques were visualized by staining for VZV IE63 protein and photographed at 10x (panels A and C) or 20x (panels B and D) magnification.

For centuries, honey has been used in traditional medicine. In recent past, honey has gain significant attention from the scientific community to explore its potential applications to treat various clinical conditions. Honey has wide range of therapeutic properties including anti-inflammatory, antibacterila, antifungal and antineoplastic activity. [24, 25] Our results suggest the presence in honey of compounds possessing anti-VZV activity, the identity of which is yet to be determined. Honey is convenient for application on skin, readily available and inexpensive, and potentially an excellent remedy to treat zoster rash in developing countries where antiviral drugs are expensive or not easily available.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grant AG032958 (R.J.C.) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Gilden DH. Varicella-Zoster virus infections of the nervous system: clinical and pathologic correlates. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125(6):770–780. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0770-VZVIOT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lua PJ, Euler GL, Jumaan AO, Harpaz R. Herpes zoster vaccination among adults aged 60 years or older in the United States, 2007: Uptake of the first new vaccine to target seniors. Vaccine. 200927(6):882–887. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinberg JM. Herpes zoster: epidemiology, natural history, and common complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6 Suppl):S130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mcinerney RJF: Honey - a Remedy Rediscovered. J Roy Soc Med. 1990;83(2):127–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiba M, Idobata K, Kobayashi N, Sato Y, Muramatsu Y. [Use of honey to ease the pain of stomatitis during radiotherapy]. Kangogaku Zasshi. 1985;49(2):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.English HKP, Pack ARC, Molan PC. The effects of manuka honey on plaque and gingivitis: a pilot study. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2004;6(2):63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molan PC. Why honey is effective as a medicine. I. Its use in modern medicine. Bee World. 1999;80(2):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molan P. Why honey is effective as a medicine - 2. The scientific explanation of its effects. Bee World. 2001;82(1):22–40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Waili NS. Investigating the antimicrobial activity of natural honey and its effects on the pathogenic bacterial infections of surgical wounds and conjunctiva. J Med Food. 2004;7(2):210–222. doi: 10.1089/1096620041224139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molan PC. The role of honey in the management of wounds. J Wound Care. 1999;8(8):415–418. doi: 10.12968/jowc.1999.8.8.25904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazrati M, Mehrabani D, Japoni A, Montasery H, Azarpira N, Hamidian-shirazi AR, Tanideh N. Effect of Honey on Healing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infected Burn Wounds in Rat. J Appl Anim Res. 2010;37(2):161–165. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lusby PE, Coombes AL, Wilkinson JM. Bactericidal activity of different honeys against pathogenic bacteria. Arch Med Res. 2005;36(5):464–467. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nejabat M, Astaneh A, Eghtedari M, Mosallaei M, Ashraf MJ, Mehrabani D. Effect of Honey in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Induced Stromal Keratitis in Rabbits. J Appl Anim Res. 2009;35(2):101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda Y, Loughrey A, Earle JA, Millar BC, Rao JR, Kearns A, McConville O, Goldsmith CE, Rooney PJ, Dooley JS, et al. Antibacterial activity of honey against community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunford C, Cooper R, Molan P. Using honey as a dressing for infected skin lesions. Nurs Times. 2000;96(14 Suppl):7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irish J, Carter DA, Shokohi T, Blair SE. Honey has an antifungal effect against Candida species. Med Mycol. 2006;44(3):289–291. doi: 10.1080/13693780500417037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeina B, Othman O, al-Assad S. Effect of honey versus thyme on Rubella virus survival in vitro. J Altern Complement Med. 1996;2(3):345–348. doi: 10.1089/acm.1996.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Waili NS. Topical honey application vs. acyclovir for the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex lesions. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(8):MT94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grose C, Brunel PA. Varicella-zoster virus: isolation and propagation in human melanoma cells at 36 and 32 degrees C. Infect Immun. 1978;19(1):199–203. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.1.199-203.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohrs RJ, Barbour MB, Mahalingam R, Wellish M, Gilden DH. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: prevalence of VZV gene 21 transcripts in latently infected human ganglia. J Virol. 1995;69(4):2674–2678. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2674-2678.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohrs RJ, Barbour M, Gilden DH. Varicella-zoster virus gene 21: transcriptional start site and promoter region. J Virol. 1998;72(1):42–47. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.42-47.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Repetto G, del Peso A, Zurita JL. Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(7):1125–1131. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mueller NH, Bos NL, Seitz S, Wellish M, Mahalingam R, Gilden D, Cohrs RJ. Recombinant Monoclonal Antibody Recognizes a Unique Epitope on Varicella-Zoster Virus Immediate-Early 63 Protein. J Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.06814-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swellam T, Miyanaga N, Onozawa M, Hattori K, Kawai K, Shimazui T, Akaza H. Antineoplastic activity of honey in an experimental bladder cancer implantation model: in vivo and in vitro studies. Int J Urol. 2003;10(4):213–219. doi: 10.1046/j.0919-8172.2003.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaganathan SK, Mandal M. Antiproliferative effects of honey and of its polyphenols: a review. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;2009:830616. doi: 10.1155/2009/830616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]