Abstract

Aims

To review the transparency of reports of behavioral interventions for pathological gambling and other gambling-related disorders.

Methods

We used the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) Statement to develop the 59-question Adapted TREND Questionnaire (ATQ). Each ATQ question corresponds to a transparency guideline and asks how clearly a study reports its objectives, research design, analytic methods, and conclusions. A subset of 23 ATQ questions is considered particularly important. We searched PubMed, PsychINFO, and Web of Science to identify experimental evaluations published between 2000 and 2011 aiming to reduce problem gambling behaviors or decrease problems caused by gambling. Twenty-six English-language reports met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed by three abstractors using the ATQ.

Results

The average report adhered to 38.4 (65%) of the 59 ATQ transparency guidelines. Each of the 59 ATQ questions received positive responses from an average of 16.9 (63.8%) of the reports. The subset of 23 particularly relevant questions received an average of 15.3 (66.5%) positive responses. Thirty of 59 (50.8%) ATQ questions were answered positively by 75% or more of the study reports, while 12 (20.3%) received positive responses by 25% or fewer. Publication year did not affect these findings.

Conclusions

Gambling intervention reports need to improve their transparency by adhering to currently neglected and particularly relevant guidelines. Among them are recommendations for comparing study participants who are lost to follow-up and those who are retained, comparing study participants with the target population, describing methods used to minimize potential bias due to group assignment, and reporting adverse events or unintended effects.

Keywords: transparency, gambling, TREND, reporting transparency, review

INTRODUCTION

Pathological gambling and other gambling-related disorders are a public health concern, with prevalence rates commensurate with many other mental illnesses [1, 2]. Because pathological gamblers often suffer significant adverse consequences [3, 4], there is a critical need to identify and develop effective interventions for these individuals [5-7].

Although the literature on gambling disorders is relatively new compared to the literature for other psychiatric or addiction problems [8, 9], gambling intervention studies are readily accessible to today’s researchers and clinicians [10, 11]. Transparent reporting of these studies is essential in assessing their validity and building a body of evidence-based treatment. To be transparent, a report must provide a clear and comprehensive description of the intervention and comparison condition, setting, participants, and outcomes. Most importantly, transparency requires that researchers report all information related to the study’s outcomes, especially the information that readers will need to assess possible biases [12]. These biases commonly result from flaws in the research design and unanticipated events associated with the intervention’s implementation.

Fortunately, reporting guidelines are available to facilitate transparency. Reporting guidelines are statements that provide advice on how to present research methods and findings. They usually take the form of a checklist, flow diagram or explicit text, and they specify a minimum set of items required for a clear account of what was done and what was found in a research study. The Transparent Reporting of Evaluations of Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) Statement is designed to improve the reporting standards of evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions [12]. TREND is intended only for reports that have a defined intervention and a research design that provides for an evaluation of efficacy or effectiveness. It is not designed for studies that do not have comparison groups in which at least one group receives an experimental or new intervention or treatment.

Most recognized guidelines, like TREND, are based on the available evidence about the characteristics of high-quality scientific research and reflect the consensus of experts in a variety of disciplines and include the support of research methodologists and journal editors. TREND was developed by an international forum of over 50 researchers in public health and drug abuse who published it in the American Journal of Public Health in 2004. It complements the widely adopted Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) developed for randomized controlled trials [13] as well as other reporting quality guides [14].

TREND consists of a 22-item checklist pertaining to the content of an evaluation report’s introduction, methods, results, and discussion. The checklist’s purpose is to enable readers to better understand a study’s design, analysis and interpretation, and, as a result, have the information they need to assess the validity and appropriateness of its results. The emerging literature on the effects of CONSORT and other guidelines confirms that recent studies tend to be more transparent than those of the past, with beneficial effects on the quality of the literature and potentially on health and health care [15-18]. Transparency is an indication of reporting quality and not necessarily of an intervention’s effectiveness. A study that finds no difference between interventions may still be transparent, while those claiming large effects may not be.

Evaluations of behavioral programs for gambling-related disorders have not yet been assessed for transparency or reporting quality despite the need that clinicians, researchers and policy-makers have for a reliable database of effective interventions. In this study, we systematically retrieved and reviewed published reports of behavioral interventions for pathological gambling and other gambling-related disorders using the Adapted TREND Questionnaire (ATQ). The ATQ consists of 59 questions, of which 23 are based on TREND standards its proponents regard as essential to transparent reporting. Our study objective was to identify strengths and weakness in reporting quality. We hypothesized, that similar to the literature in other fields, the introduction of TREND in 2004 would be accompanied by an improvement in transparency.

METHODS

This systematic review of the transparency of gambling intervention reports followed the principles described in the Center for Reviews and Dissemination on undertaking reviews in health care [19] and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) guidelines [20]. UCLA’s Review Board granted the study an exemption because we did not involve human subjects in the research.

The TREND Statement and the Adapted TREND Questionnaire (ATQ)

We chose the TREND statement because of its applicability to the research designs that are most commonly used to evaluate the effectiveness of behavioral interventions [12]. For practical reasons, we organized the 22-item TREND checklist into The Adapted TREND Questionnaire (ATQ) questionnaire (Appendix). The ATQ consists of 59 questions so that each TREND category (e.g. baseline data) and subcategory has a separate question (e.g., Does the report describe the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in each study condition?). Each ATQ question corresponds to a guideline for transparent reporting.

Eight of TREND’s 22 items and 23 of ATQ’s corresponding questions are presented in boldface type, indicating that, they are particularly relevant to behavioral and public health intervention studies [12]. As in the TREND statement, especially relevant ATQ questions are bolded (Appendix). The ATQ also includes three questions about funding source, public registration, and involvement of an ethical review board. These questions were added to the ATQ to address possible biases associated with ambiguous reporting, and they are consistent with other reporting guidelines [21-23]. The ATQ’s response choices are “yes,” “no” and “not applicable.” A “yes” or a “not applicable” response means adherence to a transparency guideline.

TREND does not have a formal scoring system. Like CONSORT, it is considered to be an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations for transparent reporting [24]. In this study, we assumed that a “yes” response to all 59 ATQ questions means transparency, and we placed special emphasis on the 23 questions that correspond to the 8 TREND items considered essential. We did not fault reports for neglecting to report information if they provided an explanation for the omission.

Study Selection

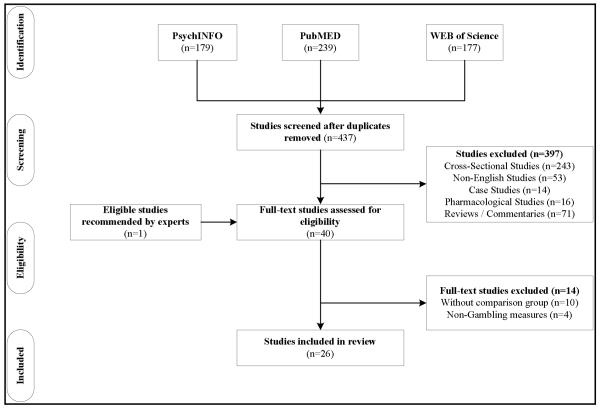

Eligible reports were published in peer-reviewed journals between January 1, 2000 and April 1, 2011 and were limited to experimental evaluations of behavioral interventions aimed at reducing problem gambling behaviors or decreasing problems caused by gambling [7]. We defined an experimental intervention as a controlled trial in which an experimental group receiving a new or innovative treatment is compared with one or more groups. All behavioral interventions for pathological or other problem gamblers were included regardless of the investigator’s use of terms (e.g., pathological gambler, problem gambler) or inclusion criteria (e.g. when gambling last occurred). Typical behavioral interventions include cognitive behavioral therapy, brief motivational enhancement therapy, and use of self-help workbooks. We excluded reports that were not in English; focused on pharmacotherapy; relied on physiological rather than behavioral measurements; or were reviews, case studies, or commentaries (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram: Number of reports identified, included, excluded and reasons for exclusion

Study retrieval

We retrieved eligible study reports from three electronic databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, and the Web of SCIENCE) on April 1, 2011. We used search strategies that were specifically applicable to each database. For PubMed we used MeSH terms; for PsychINFO, Descriptors; and Web of Science, Topic Terms. Our MeSH terms were “gambling” AND “intervention studies” OR “therapeutics” or “treatment outcome” OR “psychotherapy.” We limited the search by these terms: humans, journal article, 2000-2012. The descriptors we used to search PsycINFO were “gambling AND (“treatment” OR “intervention” OR “effectiveness evaluation”) NOT “drug therapy.” The search was limited by these terms: humans, peer-reviewed journal articles, 2000-2012. The Web of Science topic terms we used were: “gambling,” AND (“therapy” OR “intervention” OR “treatment” OR “treatment outcome”). The limitations were: NOT “Drug Therapy.” We restricted our review to articles in peer-reviewed journals published between 2000 and 2011.

We compiled the reports that were retrieved from the three databases and deleted duplicates in EndNote Version X3. We then reviewed titles and abstracts for potential eligibility and excluded ineligible reports. Finally, we assessed and reviewed full-text reports for eligibility. To ensure that all searches were consistently performed, two trained researchers (IP and MC) conducted independent searches on all eligible reports and compared results. Two unaffiliated gambling research and treatment experts reviewed the list of remaining studies for comprehensiveness and representativeness.

Data abstraction

Three reviewers (IP, MC, AS) used the ATQ to answer each question for each study report. All reviewers were trained to do the abstractions and supervised throughout the process. The online Cochrane Collaboration’s glossary of terms and the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) website were used to help standardize interpretation of the ATQ terms [24]. After the three reviewers independently completed the ATQ for each study report, their findings were compared, and differences were resolved by consensus. A fourth reviewer (AF) resolved any differences that could not be negotiated and also evaluated the accuracy of a sample of 50% of the reviews.

Data analysis

We used STATA Version 18.0 to enter and calculate statistics. We calculated the total proportion of positive responses to the ATQ by each study report and computed the average across all reports. We also calculated the total proportion of positive responses for each of the 59 individual ATQ questions across all 26 reports and calculated the average across all questions. We then compared the proportions and characteristics of the ATQ questions receiving positive responses from 75% or more of the study reports with those receiving positive responses from 25% or fewer.

To examine the relationship between publication year and transparency, we examined if the proportion of positive responses to the ATQ increased between 2000 and 2011. We plotted each study’s publication year and the proportion of its positive responses to the ATQ. Then we conducted a regression analysis using a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) to determine whether the year of publication predicted the proportion of positive responses. GLM can be used for small data sets with proportional values to examine the relationship between the total proportion of positive responses and time [25]. We also examined if the proportion of positive responses to each ATQ question changed from 2000 to 2011. We created a binomial variable for each ATQ question based on whether or not a report received a positive response (1 versus 0), with the binomial variable as the dependent variable and the year the report was published as the predictive independent variable. In this binomial regression, we excluded questions that received positive responses from all or none of the reports (n = 13) because the variance of the residuals were constant. We used a p-value of less than 0.05 to estimate the significance of the prediction.

RESULTS

The initial search produced 437 reports including 40 intervention studies, 243 cross sectional studies, 14 case studies, 16 pharmacological studies, 53 non-English language studies, and 71 reviews and commentaries (Figure 1).

Of the 40 interventions, 14 were excluded because they did not include a comparison group (N = 10), or used physiological rather than behavioral measures (N = 4). We excluded the non-English language studies (n =53) because we could not evaluate them. This exclusion process resulted in 26 eligible studies, which are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reviewed studies (N=26).

| ID | Reference | Design* | Recruitment | Inclusion criteria | Participants | Comparison Arms (Interventions) |

Mode of Intervention |

Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Carlbring et al. 2009 [33] Linkoping, Sweden |

RCT | Sought treatment at dependency clinic |

• Met one or more DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling |

• 150 self- recruited patients at an outpatient dependency clinic |

|

Individual and group |

|

|

| B | Carlbring & Smit 2008 [34] Linkoping, Sweden |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 66 self- selected pathological gamblers from the community |

|

Internet, telephone, and email |

|

• Internet-based intervention resulted in favorable changes in pathological gambling, anxiety, depression, and quality of life compared to control |

| C | Cunningham et al. 2009 [35] Alberta, Canada |

RCT | Recruited from previous study |

• Five or more DSM-IV criteria met for pathological gambling |

• 61 self- selected pathological gamblers from the community |

|

Internet and self- help materials |

|

• Respondents in the feedback condition displayed some evidence that they were spending less money on gambling than those in the control condition |

| D | Diskin & Hodgins 2009 [36] Alberta, Canada |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 81 self- selected gamblers from the community |

|

Individual |

|

|

| E | Doiron & Nicki 2007 [37] Prince Edward Island, Canada |

RCT | Ads in media and at gambling venues |

|

• 40 self- selected video lottery terminal gamblers in the community |

|

Group |

|

• The experimental group endorsed fewer gambling-related cognitive distortions, engaged in less video lottery terminal gambling, and had lower scores on CPGI |

| F | Downling et al. 2007 [38] Victoria, Australia |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 56 self- selected female community members |

|

Group and Individual |

|

|

| G | Downling et al. 2006 [39] Victoria, Australia |

n-RCT | Media ads |

|

19 females presenting for pathological gambling treatment who preferred gaming machines |

|

Individual |

|

• The CBT group showed significant improvement on gambling behavior and psychological functioning compared to control |

| H | Echeburua et al. 2000 [40] San Sebastian, Spain |

n-RCT | Sought treatment at gambling center |

|

69 patients post- treatment for slot-machine preferred gambling problems |

|

Group and individual |

|

• Abstinence success higher in both individual and group treatments compared to the control group |

| I | Grant et al. 2009 [41] Minnesota, US |

RCT | ? |

|

68 individuals |

|

Group |

|

|

| J | Hodgins et al. 2009 [42] Alberta, canada |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 314 self- selected gamblers from the community |

|

Telephone and mail |

|

|

| K | Hodgins et al. 2007 [43] Alberta, Canada |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 169 self- selected pathological gamblers from the community |

|

Telephone and mail |

|

• Participants receiving the repeated mailings were more likely to meet their goal, but they did not differ from participants receiving the single mailing in frequency of gambling or extent of gambling osses. |

| L | Hodgins et al. 2004 [44] Alberta, Canada |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 102 self- selected gamblers from the community |

|

Telephone and mail |

|

|

| M | Hodgins et al. 2001 [45] Alberta, Canada |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 102 self- selected gamblers from the community |

|

Telephone and mail |

|

|

| N | Korman et al. 2008 [46] BC, Canada |

RCT | Referred and Media Ads |

• Seeking treatment for gambling and anger problems |

• 42 self- selected gamblers with anger problems from the community |

|

Individual |

|

• Relative to the control, participants in the integrated anger and addictions treatment reported significantly less gambling and less trait anger and substance use post-treatment |

| O | Ladouceur et al. 2003 [47] Québec, Canada |

RCT | Referred and sought treatment |

• DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling |

• 58 self- selected pathological gamblers who sought |

|

Group |

|

|

| P | Ladouceur et al. 2001 [48] Québec, Canada |

RCT | Referred and sought treatment |

• DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling |

• 66 self- selected pathological gamblers who sought treatment at treatment center |

|

Individual |

|

• Significant changes in the treatment group on all outcome measures and maintenance of therapeutic gains at 6- and 12- mont |

| Q | Marceaux & Melville 2011 [49] LA, US |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 49 self- selected pathological gamblers from the community |

|

Group |

|

|

| R | Melville et al. 2004 [50] LA, US |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 20 self- selected pathological gamblers from the community |

|

Group |

|

|

| S | Milton et al. 2002 [51] N.S.W., Australia |

RCT | Media ads and referred |

• DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling |

• 47 pathological gamblers presenting at a University- based gambling treatment clinic |

|

Individual |

|

|

| T | Myrseth et al. 2009 [52] Bergen, Norway |

RCT | Sought treatment |

|

• 14 gamblers self-selected gamblers seeking treatment at the university clinic |

|

Group |

|

|

| U | Oei et al. 2010 [53] Brisbane, Australia |

RCT | ? | ? | • 102 self- selected community members |

|

Group and Individual |

|

|

| V | Petry et al. 2009 [54] Connecticut, US |

RCT | Via screening efforts and flyers posted on campuses |

|

• 117 self- selected college student gamblers |

|

Individual |

|

|

| W | Petry et al. 2008 [55] Connecticut, US |

RCT | Screening at substance abuse and medical clinics |

|

• 180 self- selected gamblers from substance abuse and medical clinics |

|

Individual |

|

|

| X | Petry et al. 2006 [56] Connecticut, US |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 231 self- selected pathological gamblers from the community |

|

Individual |

|

|

| Y | Toneatto & Dragonetti 2009 [57] Ontario, Canada |

RCT | Media ads |

|

• 99 self- selected pathological gamblers from the community |

|

Individual |

|

• A cognitive approach did not yield superior outcomes than did treatments that did not explicitly address cognitive distortions |

| Z | Toneatto & Dragonetti 2008 [58] Ontario, Canada |

RCT | Ads in media and at mental health agencies |

|

• 126 self- selected problem gamblers from the community |

|

Group |

|

|

We accepted the authors’ description of their research design

Abbreviations: CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; MI: Motivational Interviewing ; MET: Motivational Enhancement Therapy Gambling behavior: (e.g. days gambled, duration gambled, dollars gambled) SOGS: South Oaks Gambling Screen; CPGI: Canadian Problem Gambling Index; GA: Gamblers anonymous ASI: Addiction Severity Index RCT: Randomized Control Trial n-RCT: Non-randomized Control Trial

Adherence to Reporting Guidelines

Table 2 shows the frequency of positive responses received by each study to all 59 ATQ questions. The 26 studies received a range of positive responses from 26 to 49 (44.1% to 83.1%) of the 59 questions, with an average of 38.4 (65.1%) positive responses, and from 8 to 18 (34.8% to 78.3%) of the 23-question subset of particularly important guidelines, with an average of 13.5 (58.7%).

Table 2.

Frequency and proportion of positive responses to the Adapted TREND Questionnaire (ATQ) by each reviewed study (N=26).

| Reference | All ATQ Questions (N = 59) |

Particularly Important ATQ Questions (N = 23) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Carlbring et al. 2009 [33] | 49 | 83.1 | 18 | 78.3 |

| Carlbring & Smit 2008 [34] | 44 | 74.6 | 16 | 69.6 |

| Cunningham et al. 2009 [35] | 36 | 61.0 | 13 | 56.5 |

| Diskin & Hodgins 2009 [36] | 40 | 67.8 | 15 | 65.2 |

| Doiron & Nicki 2007 [37] | 38 | 64.4 | 14 | 60.9 |

| Downling et al. 2007 [38] | 36 | 61.0 | 14 | 60.9 |

| Downling et al. 2006 [39] | 36 | 61.0 | 14 | 60.9 |

| Echeburua et al. 2000 [40] | 35 | 59.3 | 11 | 47.8 |

| Grant et al. 2009 [41] | 32 | 54.2 | 10 | 43.5 |

| Hodgins et al. 2009 [42] | 43 | 72.9 | 16 | 69.6 |

| Hodgins et al. 2007 [43] | 37 | 62.7 | 14 | 60.9 |

| Hodgins et al. 2004 [44] | 37 | 62.7 | 11 | 47.8 |

| Hodgins et al. 2001 [45] | 38 | 64.4 | 14 | 60.9 |

| Korman et al. 2008 [46] | 46 | 78.0 | 19 | 82.6 |

| Ladouceur et al. 2003 [47] | 35 | 59.3 | 13 | 56.5 |

| Ladouceur et al. 2001 [48] | 36 | 61.0 | 11 | 47.8 |

| Marceaux & Melville 2011 [49] | 36 | 61.0 | 11 | 47.8 |

| Melville et al. 2004 [50] | 28 | 47.5 | 9 | 39.1 |

| Milton et al. 2002 [51] | 45 | 76.3 | 16 | 69.6 |

| Myrseth et al. 2009 [52] | 36 | 61.0 | 13 | 56.5 |

| Oei et al. 2010 [53] | 26 | 44.1 | 8 | 34.8 |

| Petry et al. 2009 [54] | 46 | 78.0 | 15 | 65.2 |

| Petry et al. 2008 [55] | 47 | 79.7 | 15 | 65.2 |

| Petry et al. 2006 [56] | 44 | 74.6 | 15 | 65.2 |

| Toneatto & Dragonetti 2009 [57] | 40 | 67.8 | 15 | 65.2 |

| Toneatto & Dragonetti 2008 [58] | 32 | 54.2 | 11 | 47.8 |

| Mean | 38.4 | 65.1 | 13.5 | 58.7 |

Each of the 59 ATQ questions received a positive response from an average of 16.9 (63.8%) of the reports and from an average of 15.3 (66.5%) of particularly important questions (Table 2).

Thirty-two out of 59 (54.2%) ATQ questions were answered positively by 75% or more of the study reports (Table 3). This includes 10 (43.5%) of the particularly important questions. For instance, 100% of studies described theories used in designing behavioral interventions (question #1), described the delivery method (#7), described specific objectives and hypotheses (#14), clearly defined the primary and secondary outcome measures (#15), described the unit of assignment (#20), reported the smallest unit that was analyzed (#24), described the statistical methods used to compare study groups (#25), summarized results for each condition for each primary and secondary outcome (#44), summarized other analyses performed (#49), interpreted the results (#51), and described the general interpretation of the results in the context of current evidence and current theory (#56).

Table 3.

Frequency and proportion of studies (N = 26) that received a positive response to each of the 59 ATQ* questions (in descending order)

| ATQ Question Number | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Described theories used in designing behavioral interventions** | 26 | 100 |

| 7. Described the delivery method | 26 | 100 |

| 14. Described specific objectives and hypotheses | 26 | 100 |

| 15. Clearly defined primary and secondary outcome measures | 26 | 100 |

| 20. Described the unit of assignment (the unit being assigned to study condition, e.g., individual, group, community) | 26 | 100 |

|

24. Reported the smallest unit that was analyzed to assess intervention effects (e.g., individual, group, or community) and analytical method used to

account for this if the unit of analysis differed from the unit of assignment |

26 | 100 |

| 25. Described the statistical methods used to compare study groups for primary outcomes, including complex methods for correlated data | 26 | 100 |

| 44. Summarized results for each condition for each primary and secondary outcome | 26 | 100 |

| 49. Summarized other analyses performed, including subgroup or restricted analyses, indicating which are pre-specified or exploratory | 26 | 100 |

| 51. Interpreted the results, taking into account study hypotheses, sources of potential bias, imprecision of measures, multiplicative analyses, and other limitations or weaknesses of the study |

26 | 100 |

| 56. Described the general interpretation of the results in the context of current evidence and current theory | 26 | 100 |

| 6. Described the content of interventions intended for each study condition | 25 | 96.2 |

| 8. Described the unit of delivery or how subjects were grouped during delivery | 25 | 96.2 |

| 11. Reported the number of sessions or events that were intended to be delivered | 25 | 96.2 |

| 26. Described the statistical methods used for additional analysis, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analysis | 25 | 96.2 |

| 37. Described baseline characteristics for each study condition relevant to the gamblers being studied | 25 | 96.2 |

| 2. Described the eligibility criteria for participants, including criteria at different levels in recruitment / sampling plan | 24 | 92.3 |

| 3. Described the method of recruitment (e.g., referral, self-selection) | 24 | 92.3 |

| 30. Reported the number of participants assigned to each study condition | 24 | 92.3 |

| 36. Described baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in each study condition | 23 | 88.5 |

| 41. Described the data on group equivalence at baseline and the statistical methods to control for baseline differences, if found | 23 | 88.5 |

| 45. Reported the estimated effect size | 23 | 88.5 |

| 52. Described the extent that the limitations affect the validity of the study (and reasons) | 23 | 88.5 |

| 31. Reported the number of participants who received each study condition | 22 | 84.6 |

| 32. Reported the number of participants who completed the follow up or did not complete the follow up by study condition | 22 | 84.6 |

| 42. Reported the number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis for each study condition, particularly when the denominators change for different outcomes; statement of the results in absolute numbers when feasible |

22 | 84.6 |

| 9. Reported the person who delivered the intervention | 21 | 80.8 |

| 17. Described the methods of data collection for each study variable | 21 | 80.8 |

| 21. Described methods used to adding units to study condition including details of any restrictions (e.g., blocking, stratification) | 21 | 80.8 |

| 16. Provided justification for outcomes measures | 20 | 76.9 |

| 29. Reported the number of participants screened for eligibility, found to be eligible or not eligible, delinked to be enrolled, and enrolled in the study | 20 | 76.9 |

| 43. Indicated whether the analysis was “intention-to-treat,” or, if not description of how non-compliers were considered in the analysis | 20 | 76.9 |

| 12. Reported the duration of each session | 19 | 73.1 |

| 27. Described the method for imputing missing data | 18 | 69.2 |

| 47. Described the null and negative findings | 18 | 69.2 |

| 57. Reported funding for the study | 17 | 65.4 |

| 18. Reported the psychometric properties of each outcome measure | 15 | 57.7 |

| 4. Reported the recruitment setting (e.g. gay bar, city) | 14 | 53.8 |

|

55. Discussed the generalizability (external validity) of the trial findings, taking into account the study population, the characteristics of the

intervention, length of follow up, incentives, compliance rates, specific sites/ settings involved in the study, and other contextual issues |

14 | 53.8 |

| 10. Described the intervention setting | 13 | 50.0 |

| 13. Reported activities to increase compliance or adherence (e.g. incentives) | 12 | 46.2 |

| 58. Reported involvement with IRB | 11 | 42.3 |

| 54. Discussed the success of and barriers to implementing the intervention; fidelity of implementation | 10 | 38.5 |

| 19. Described how the sample size was determined and, when applicable, explained any interim analyses and stopping rules | 9 | 34.6 |

| 23. Reported whether participants or researchers were blinded to study condition assignment, and if so, described how the blinding was accomplished and assessed |

9 | 34.6 |

| 28. Reported the statistical software used | 9 | 34.6 |

| 34. Reported the dates defining the periods of recruitment | 8 | 30.8 |

| 38. Described baseline characteristics of those lost to follow-up and those retained, overall | 6 | 23.1 |

|

53. Interpreted the results, taking into account study hypotheses, sources of potential bias, imprecision of measures, multiplicative analyses, and other

limitations or weaknesses of the study |

6 | 23.1 |

| 46. Reported a confidence interval to indicate precision | 5 | 19.2 |

| 5. Described the sampling method | 4 | 15.4 |

| 40. Presented a comparison between study population at baseline and target population of interest | 4 | 15.4 |

| 22. Described methods to minimize potential bias due to non-randomization or randomization (e.g. matching) | 3 | 11.5 |

| 39. Described baseline characteristics of those lost to follow-up and those retained, by study condition | 3 | 11.5 |

| 59. Reported registration number and name of trial registry | 3 | 11.5 |

| 48. Described how the investigators tested pre-specified causal pathways through which the intervention was intended to operate, if any (e.g, as for CBT) | 2 | 7.7 |

| 33. Described protocol deviations from study as planned along with reasons | 1 | 3.8 |

| 50. Reported all important adverse events or unintended effects in each study condition | 1 | 3.8 |

| 35. Reported dates defining the periods of treatment and follow-up | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mean for all questions | 16.9 | 63.8 |

| Mean for particularly important questions | 15.3 | 66.5 |

Adapted TREND Questionnaire

Bold items correspond to the TREND Statement’s list particularly important transparency standards

Table 3 also shows that twelve of the 59 ATQ (20.3%), questions including 7 of 23 (30.4%) of the particularly relevant ones, received positive responses from 25% or fewer of the study reports. Among the questions receiving these relatively low responses are those asking if the studies described their methods of minimizing potential bias due to non-randomization or randomization (question #22), described the baseline characteristics of participants who were lost to follow-up (#38), and presented a comparison between the study population at baseline and the target population of interest (#40).

Change in Adherence over Time

We found no relationship between the number of positive responses to the ATQ and the year of a report’s publication (Table 4), nor did we find a change over time in the number of positive responses to an individual ATQ question (Table 5). The introduction of the TREND statement in 2004 did not influence the transparency of individual reports or the number of positive responses to ATQ questions.

Table 4.

Likelihood that year of publication predicts proportion of positive responses using a generalized linear model.

| Coefficient | Standard Error | Z | P> Z | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 0.167 | 0.0282 | 0.59 | 0.554 | −0.0386 – 0.0720 |

| Constant | −32.88 | 56.66 | −0.58 | 0.562 | −143.9 – 78.2 |

Table 5.

Likelihood of a positive response to each ATQ question* based on publication year (2000-2011) using binomial regression

| ATQ Question |

Odds Ratio | Std. Err. | z | P>|z| | [95% Conf. | Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.96 | 0.24 | −0.17 | 0.87 | 0.58 | 1.58 |

| 3 | 0.35 | 0.28 | −1.34 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 1.63 |

| 4 | 0.76 | 0.12 | −1.71 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 1.04 |

| 5 | 0.98 | 0.17 | −0.11 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 1.39 |

| 6 | 0.23 | 0.26 | −1.28 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 2.16 |

| 8 | 0.58 | 0.44 | −0.73 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 2.55 |

| 9 | 0.75 | 0.18 | −1.18 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 1.21 |

| 10 | 0.85 | 0.12 | −1.17 | 0.24 | 0.64 | 1.12 |

| 12 | 1.12 | 0.16 | 0.8 | 0.42 | 0.85 | 1.48 |

| 13 | 1.15 | 0.16 | 1.04 | 0.30 | 0.88 | 1.52 |

| 16 | 1.14 | 0.17 | 0.89 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 1.52 |

| 17 | 0.48 | 0.22 | −1.57 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 1.20 |

| 18 | 0.77 | 0.13 | −1.58 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 1.06 |

| 19 | 1.21 | 0.20 | 1.19 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 1.66 |

| 21 | 1.23 | 0.19 | 1.3 | 0.19 | 0.90 | 1.67 |

| 22 | 1.54 | 0.60 | 1.09 | 0.28 | 0.71 | 3.32 |

| 23 | 0.98 | 0.13 | −0.12 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 1.28 |

| 26 | 0.23 | 0.26 | −1.28 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 2.16 |

| 27 | 1.17 | 0.16 | 1.13 | 0.26 | 0.89 | 1.53 |

| 28 | 1.37 | 0.27 | 1.63 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 2.01 |

| 29 | 0.93 | 0.15 | −0.47 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 1.28 |

| 30 | 1.02 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.64 | 1.62 |

| 32 | 0.92 | 0.18 | −0.42 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 1.35 |

| 33 | 0.42 | 0.36 | −1.02 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 2.24 |

| 34 | 1.08 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.81 | 1.44 |

| 36 | 0.91 | 0.21 | −0.41 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 1.42 |

| 37 | 0.23 | 0.26 | −1.28 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 2.16 |

| 38 | 1.27 | 0.26 | 1.17 | 0.24 | 0.85 | 1.88 |

| 39 | 1.35 | 0.43 | 0.95 | 0.34 | 0.72 | 2.54 |

| 40 | 0.95 | 0.16 | −0.29 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 1.33 |

| 41 | 1.08 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 1.57 |

| 43 | 1.19 | 0.18 | 1.18 | 0.24 | 0.89 | 1.59 |

| 46 | 1.02 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 1.41 |

| 48 | 1.23 | 0.41 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 2.35 |

| 52 | 1.34 | 0.26 | 1.47 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 1.97 |

| 54 | 1.05 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 1.36 |

| 57 | 0.96 | 0.13 | -0.29 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 1.26 |

| 59 | 1.87 | 0.95 | 1.24 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 5.05 |

Questions #1, 7, 11, 14, 15, 20, 24, 25, 31, 35, 42, 44, 45, 47, 49, 50, 51, 53, 55, 56, and 58 were excluded from analysis because the variance of the residuals were constant (received all positive responses or all negative responses).

DISCUSSION

This review of 26 English-language reports of behavioral intervention research on gambling published between 2000 and 2011 suggests a need for improved reporting transparency. The average report received positive responses to just over 61.5% of 59 ATQ questions, and the average ATQ question received a positive response from about 64% of studies. Further, about 30% of the particularly important questions were answered positively in just 25% of the reviewed studies.

The gambling behavioral intervention literature’s need for improvement is most evident in its methodological deficits. For instance, fewer than 25% of the reviewed reports described their sampling methods and how they minimized potential bias due to non-randomization or randomization. Without sufficient information about the methods that are used to assign participants to groups, readers cannot fairly evaluate the likelihood of bias in group assignment [26]. In keeping with current standards, reports should describe who generated the allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions.

Users of effectiveness research must be able to evaluate whether an intervention is likely to be effective in their patients. This may not be possible for consumers of much of the gambling intervention literature because fewer than 25% of study reports described the baseline characteristics of study participants lost to follow-up and retained overall or by study condition. Further, the reports did not compare whether the study participants were likely to be similar in important characteristics (such as age, gender, severity of gambling disorder) from those in the target population.

Gambling behavioral intervention reports need to be more transparent in their descriptions of who participated in the research, who dropped out, and if the drop out rates differed between experimental and control groups. TREND advocates using a flow diagram that can assist investigators in reporting the study patients’ progress throughout the course of the research. The diagram enables readers to more accurately evaluate the potential impact of the intervention on their patients. The gambling literature also needs to be explicit about unanticipated consequences of participation and provide an explanation for the interventions effects in patients who have the selected characteristics.

Reporting quality did not change over time unlike other fields in which reporting quality has improved in recent years with the introduction of guidelines [15-18]. It is important to note, however, that although reporting in other fields has improved, uniform standards for comparing reporting quality across fields are unavailable [16], and the gambling literature’s place on the quality spectrum cannot be known.

Adherence to reporting quality is essential if the gambling field is to progress, especially within the context of the growth of evidence-based health care [27] and its reliance on meta-analyses. A meta-analysis is the use of statistical techniques in a systematic literature review to integrate the results of included studies. Its application requires that investigators report their sampling strategies and statistical methods in great detail. Unfortunately, many guidelines for statistical transparency, such as describing the sampling methods, are neglected in the gambling literature, inhibiting its usefulness for meta-analysis.

Reporting guidelines are important to a field’s growth because they can have a beneficial effect on the way research is conducted. For instance, as the American Psychological Association has noted [28], the TREND guideline suggesting that dropout rates be reported may encourage researchers to consider what levels of attrition are acceptable, and thus they may come to employ more effective procedures for maximizing the number of participants who complete their study.

Reporting guidelines are not without their critics. Some researchers have raised questions about the criteria for assessing reporting quality [16]. They point out that reviewers tend to use heterogeneous criteria and do not rely on uniform definitions, thereby possibly limiting the relevance of their reviews [16]. Another concern raised by researchers is that strict adherence to guidelines may lead to excessive standardization. For example, compliance with reporting standards may fill articles with details of methods and results that are inconsequential to interpretation, resulting in a loss of critical facts to an excess of minutiae [28]. TREND, however, is a minimum set of standards, so its use does not preclude providing other information that investigators believe will maximize the reader’s understanding of their study’s objectives, methods, and findings.

Despite some concerns about reporting guidelines, almost all major biomedical and public health journals have accepted and even promoted their use. The CONSORT Statement, for example, has been adopted by over 450 journals, and TREND is amassing an increasing number of supporters including Addiction, the American Journal of Public Health and the Journal of Alcohol and Drug Addiction [29].

Behavioral gambling intervention reports can improve their transparency by focusing on particularly important guidelines currently neglected in the literature. These include describing the baseline characteristics of study participants who are lost to follow-up and those who remain throughout the study, comparing participants at baseline with the target population; describing the methods used to minimize potential bias due to group assignment, and reporting adverse events or unintended effects that occur in the experimental and control groups.

Limitations

This review examined published reports in English. It is possible that there are unpublished studies in other languages whose reporting quality may have elevated the gambling literature’s average transparency. However, we had outside experts review our list of eligible study reports, and they found it to be complete and representative.

We reviewed 26 reports. This number represents only a segment of the gambling literature. Other reviewers may have selected different search terms, scoring criteria, or reporting standards. We did not review case or cross sectional studies primarily because checklists like TREND are not currently available for these research designs, which are not typically used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

The number of reports included in this study, however, is consistent with reviews in other fields. For example, a review of the effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care included 21 studies [30]. The Cochrane Collaboration’s review of psychosocial smoking cessation interventions to help people with coronary heart disease stop smoking included 16 studies [31], and its review of combined-pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for-posttraumatic stress disorder relies on four studies [32].

Another potential limitation of this review is that we may have penalized studies for neglecting to report negative events and deviations from protocol as required by the ATQ. It is conceivable that the reports did not contain this information because the investigators did not observe any adverse events and implemented their studies as planned. Without explanatory information from the authors, however, we were unable to distinguish between intentional reporting omissions and lack of transparency. Additionally, standardized transparency scores are not available, and our criteria for evaluating reporting quality may be considered arbitrary or set too high. Finally, individual reports may have had unique characteristics that the TREND statement is not designed to uncover, and if so, our review necessarily failed to identify and discuss them.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jeremiah Weinstock and David Ledgerwood for reviewing our list of reported studies for completeness and accuracy. Margarit Davtian reviewed and edited previous drafts. Lorna Kwan Herbert and Qiaolin Chen offered invaluable statistical advice.

This project was partially funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant #: K23DA 19522-2) and the California Office of Problem Gambling.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: There are no affiliations, members, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this project or providing a conflict of interest. There are no contractual constrains on publishing required by the funder.

References

- 1.Korn DA, Shaffer HJ. Gambling and the health of the public: Adopting a public health perspective. J Gambling Studies. 1999;15:289–365. doi: 10.1023/a:1023005115932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer H, Hall M. Updating and refining prevalence estimates of disordered gambling behaviour in the United States and Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. Revue Canadienne de Santé Publique. 2002;92:168–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03404298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler R, Hwang I, Labrie R, et al. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1351–60. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parhami I, Siani A, Rosenthal RJ, Fong TW. Pathological gambling, problem gambling and sleep complaints : An analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey : Replication (NCS-R) J Gambling Studies. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9299-8. online first. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladouceur R, Shaffer HJ. Treating problem gamblers: working towards empirically supported treatment. J Gambling Studies. 2005;21:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s10899-004-1915-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potenza MN, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Pathological gambling. JAMA. 2001;286:141–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker M, Toneatto T, Potenza M, et al. A framework for reporting outcomes in problem gambling treatment research: the Banff, Alberta Consensus. Addiction. 2006;101:504–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesieur HR, Rosenthal RJ. Pathological gambling: A review of the literature (prepared for the American Psychiatric Association task force on DSM-IV committee on disorders of impulse control not elsewhere classified) J Gambling Studies. 1991;7:5–39. doi: 10.1007/BF01019763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer HJ, Martin R. Disordered Gambling: Etiology, Trajectory, and Clinical Considerations. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-040510-143928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewer JA, Grant JE, Potenza MN. The treatment of pathologic gambling. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2008;7:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung KS, Cottler LB. Treatment of pathological gambling. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:69–74. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32831575d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altman DG. Better reporting of randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 1996;313:570–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Equator [accessed 2012-2-6];Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research. Network, E. 2011 Available at: http://www.equator-network.org/resource-centre/library-of-health-research-reporting/reporting-guidelines/ Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65GbZfQCO.

- 15.Han C, Kwak K-P, Marks DM, et al. The impact of the CONSORT statement on reporting of randomized clinical trials in psychiatry. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dechartres A, Charles P, Hopewell S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reviews assessing the quality or the reporting of randomized controlled trials are increasing over time but raised questions about how quality is assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;64:136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladd BO, Mccrady BS, Manuel JK, Campbell W. Improving the quality of reporting alcohol outcome studies: Effects of the CONSORT statement. Addict Behav. 2010;35:660–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consort [accessed 2012-2-6];Impact of and adherence to CONSORT Statement. 2011 Available at: http://www.consort-statement.org/about-consort/impact-of-consort/impact-of-and-adherence-to-consort/ Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65Gk1tNBU.

- 19. [accessed 2012-2-6];Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. 2011 Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/SysRev/!SSL!/WebHelp/SysRev3.htm. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65GkDHsCz.

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle PFA, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. NEJM. 2004;351:1250–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326:1167–77. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taljaard M, Mcrae AD, Weijer C, et al. Inadequate reporting of research ethics review and informed consent in cluster randomised trials: review of random sample of published trials. BMJ. 2011;342:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. [accessed 2012-2-6];The CONSORT Statement Overview. 2012 Available at: http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/ Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65GZ7NmPo.

- 25.Mccullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010:340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray J. a. M., Haynes R, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. It’s about integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper H, Appelbaum M, Maxwell S, Stone A, Sher K. Reporting Standards for Research in Psychology: Why Do We Need Them? What Might They Be. Am Psychol. 2008;63:839–51. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.9.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cdc [accessed 2012-02-06];Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) Supporters. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/trendstatement/supporters.html. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65Ga1De6U.

- 30.Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. CD004148 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summaries C. [accessed 2012-03-06];Psychosocial smoking cessation interventions such as behavioural counselling, telephone support and self-help interventions are effective in helping people with coronary heart disease stop smoking. Available at: http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD006886/psychosocial-smoking-cessation-interventions-such-as-behavioural-counselling-telephone-support-and-self-help-interventions-are-effective-in-helping-people-with-coronary-heart-disease-stop-smoking. http://www.webcitation.org/65GaQLZ4X.

- 32.Hetrick SE, Purcell R, Garner B, Parslow R. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010:7. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007316.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlbring P, Jonsson J, Josephson H, Forsberg L. Motivational interviewing versus cognitive behavioral group therapy in the treatment of problem and pathological gambling: A randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;39:92–103. doi: 10.1080/16506070903190245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlbring P, Smit F. Randomized trial of internet-delivered self-help with telephone support for pathological gamblers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:1090–4. doi: 10.1037/a0013603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham JA, Hodgins DC, Toneatto T, Rai A, Cordingley J. Pilot study of a personalized feedback intervention for problem gamblers. Behavior Therapy. 2009;40:219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diskin KM, Hodgins DC. A randomized controlled trial of a single session motivational intervention for concerned gamblers. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:382–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doiron JP, Nicki RM. Prevention of pathological gambling: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2007;36:74–84. doi: 10.1080/16506070601092966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowling N, Smith D, Thomas T. A comparison of individual and group cognitive-behavioural treatment for female pathological gambling. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dowling N, Smith D, Thomas T. Treatment of female pathological gambling: The efficacy of a cognitive-behavioural approach. J Gambling Studies. 2006;22:355–72. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Echeburúa E, Fernández-Montalvo J, Báez C. Relapse prevention in the treatment of slot-machine pathological gambling: Long-term outcome*. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:351–64. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant JE, Donahue CB, Odlaug BL, et al. Imaginal desensitisation plus motivational interviewing for pathological gambling: randomised controlled trial. Bri J Psychiatry. 2009;195:266–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodgins DC, Currie SR, Currie G, Fick GH. Randomized trial of brief motivational treatments for pathological gamblers: More is not necessarily better. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:950–60. doi: 10.1037/a0016318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodgins DC, Currie SR, El-Guebaly N, Diskin KM. Does Providing Extended Relapse Prevention Bibliotherapy to Problem Gamblers Improve Outcome? J Gambling Studies. 2007;23:41–54. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodgins DC, Currie S, El-Guebaly N, Peden N. Brief Motivational Treatment for Problem Gambling: A 24-Month Follow-Up. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:293–6. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hodgins DC, Currie SR, El-Guebaly N. Motivational enhancement and self-help treatments for problem gambling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:50–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korman L, Collins J, Littman-Sharp N, et al. Randomized control trial of an integrated therapy for comorbid anger and gambling. Psychother Res. 2008;18:454–65. doi: 10.1080/10503300701858362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ladouceur R, Sylvain C, Boutin C, et al. Group therapy for pathological gamblers: a cognitive approach. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:587–96. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ladouceur R, Sylvain C, Boutin C, et al. Cognitive treatment of pathological gambling. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:774–80. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marceaux JC, Melville CL. Twelve-Step Facilitated Versus Mapping-Enhanced Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Pathological Gambling: A Controlled Study. J Gambling Studies. 2011;27:171–90. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9196-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melville CL, Davis CS, Matzenbacher DL, Clayborne J. Node-link-mapping-enhanced group treatment for pathological gambling. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:73–87. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milton S, Crino R, Hunt C, Prosser E. The effect of compliance-improving interventions on the cognitive-behavioural treatment of pathological gambling. J Gambling Studies. 2002;18:207–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1015580800028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myrseth H, Litlerè I, Støylen IJ, Pallesen S. A controlled study of the effect of cognitive-behavioural group therapy for pathological gamblers. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2009;63:22–31. doi: 10.1080/08039480802055139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oei TPS, Raylu N, Casey LM. Effectiveness of group and individual formats of a combined motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral treatment program for problem gambling: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2010;38:233–8. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809990701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petry NM, Weinstock J, Morasco BJ, Ledgerwood DM. Brief motivational interventions for college student problem gamblers. Addiction. 2009;104:1569–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petry NM, Weinstock J, Ledgerwood DM, Morasco B. A randomized trial of brief interventions for problem and pathological gamblers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:318–28. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petry NM, Ammerman Y, Bohl J, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for pathological gamblers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:555–68. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toneatto T, Gunaratne M. Does the Treatment of Cognitive Distortions Improve Clinical Outcomes for Problem Gambling? J Contem Psychother. 2009;39:221–9. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toneatto T, Dragonetti R. Effectiveness of Community Based Treatment for Problem Gambling: A Quasi Experimental Evaluation of Cognitive Behavioral vs. Twelve Step Therapy. Amer J Addictions. 2008;17:298–303. doi: 10.1080/10550490802138830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.