Many pathological conditions like sleep apnea, preeclampsia, high altitude sickness and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that cause intermittent or chronic hypoxia are often associated with the development of either systemic or pulmonary hypertension.[1] Mechanisms sensing hypoxia may be important contributors to the development of pulmonary hypertension and to tissue injury and repair associated with hypertensive disease and in integrated aspects of cardiovascular function. This review will focus on highlighting how some of the better documented oxygen sensing mechanisms associated with vascular regulation could be influenced by poorly understood interactions between hypoxia and hypertension. It will also consider some of the identified integrated interactions between hypoxia and hypertensive disease processes that could contribute to the progression of disease processes such as renal hypertension.

High altitude and COPD are thought to promote pulmonary hypertension by exposing the pulmonary circulation to chronic hypoxia as a result of the low partial pressure of oxygen at high altitude and increases in the diffusion distance for oxygen, respectively.[2,3] While high altitude can initially promote increased systemic blood pressure, this change appears to reverse with time.[4] Interestingly, hypobaric hypoxia conditions of high altitude were observed to prevent the development of hypertension and skeletal muscle arteriolar rarefaction in spontaneously hypertensive rats.[5] Living at high altitude seems to lower blood pressure only in children,[6] and it did not appear to attenuate hypertension in obese adults consuming high fat diets.[7] Based on studies in animal models of acute and chronic hypoxia, hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV) is initially activated. Eventually endothelial dysfunction-associated with a loss of NO and increases reactive oxygen species (ROS), endothelin, serotonin and contractile prostaglandins contribute to maintaining elevated pulmonary artery pressure through increased intracellular Ca2+ levels and rho kinase-associated myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity.[8] Although the mechanisms involved in PO2 sensing and eliciting constriction are incompletely understood, there is consensus that hypoxia-evoked redox and ROS changes play a significant role in HPV and pulmonary hypertension development.[8,9] Besides vasoconstriction, remodeling of pulmonary arteries also has a significant role in increasing pulmonary arterial pressure. Numerous studies are ongoing to identify inflammatory and progenitor cell mechanisms involved in muscularization of resistance arteries as well as adventitial fibroblast-promoted matrix remodeling and neointimal plexiform lesion formation.[8] The emerging picture from these studies suggests that ROS and oxidant-associated redox signaling through mechanisms including HIF and rho kinase could be promoting the remodeling that aggravates hypertension. Interestingly, therapies promoting guanylate cyclase activation under oxidant conditions or preventing cGMP degradation by treatment with sildenafil seem to be beneficial in attenuating many aspects of pulmonary hypertensive disease processes.[10] The function of signaling mechanisms associated with HPV are thought to be important factors in modulating pulmonary hypertension development.[8,9]

Vascular Oxygen Sensing Mechanisms and Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction

The sensing of hypoxia is a primary mechanism for regulating blood flow in the pulmonary circulation through HPV. The HPV response matches the perfusion of the pulmonary circulation to oxygen delivery by lung ventilation. While the mechanism of HPV is not yet established, studies generally support roles for hypoxia modulating the generation of ROS and cellular oxidation-reduction (redox) signaling mechanisms regulating pulmonary arterial smooth muscle force.[9,11–13] Several opposing theories exist for pulmonary artery oxygen sensors in HPV involving roles for mitochondria and/or Nox oxidases generating either increases or decreases in ROS under hypoxia, which function to regulate redox signaling mechanisms controlling the vasoconstriction to hypoxia that is observed. The redox theory for HPV proposed by Archer and Weir[13] based primarily on studies in rat and mouse pulmonary arteries suggested hypoxia was lowering the generation of mitochondrial-derived ROS, and this removed a peroxide-mediated vasodilator mechanism involving cytosolic NAD(P)H and/or thiol oxidation opening voltage-regulated potassium channels. Studies by this group also demonstrated that Nox2-deficient mice showed a normal HPV response. Our studies in bovine pulmonary arteries (BPA) detected evidence that hypoxia was promoting HPV by removing a peroxide-elicited relaxation. The relaxation removed by hypoxia appears to originate from both cGMP–dependent and cGMP-independent stimulation of protein kinase G (PKG) as a result of peroxide promoting both a stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) and a thiol-oxidation mediated dimerization-activation of PKG, respectively.[11] Modulation of oxidases by siRNA and pharmacological methods provided evidence that Nox4, but not Nox2 or mitochondria, was the source of peroxide controlling the HPV response seen in BPA.[11]. Hypoxia also causes an increase in NADPH in pulmonary arteries potentially through activating G6PD[14] or decreasing[13] mitochondrial ROS. In contrast, Schumaker’s group reported evidence in cultured rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells for hypoxia promoting release of mitochondrial-derived peroxide, which was suggested to elicit vasoconstriction through increasing intracellular calcium levels and Rho kinase activity.[12] Thus, several current theories for the mechanism of HPV include changes in the generation of ROS and cytosolic redox mechanisms in sensing changes in PO2 by pulmonary arterial smooth muscle, but, controversy exists in defining the oxidase involved and in the direction of changes in ROS and redox elicited by hypoxia.

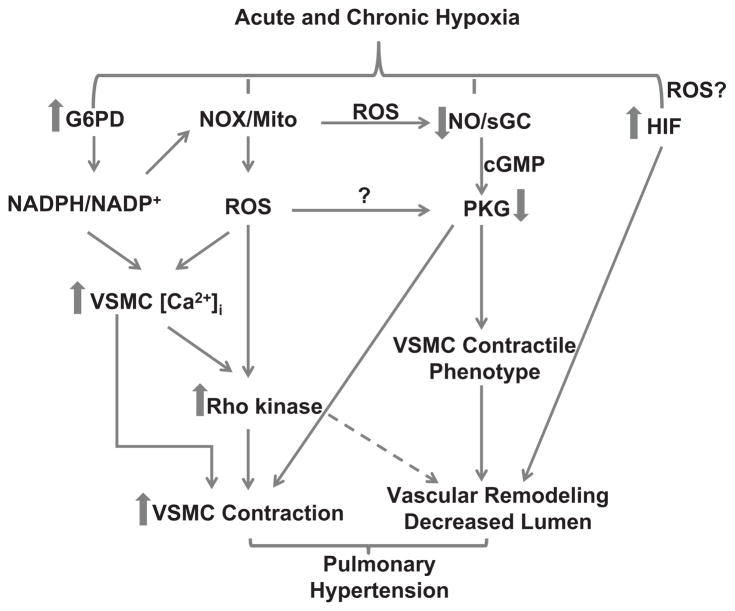

Differences in the effects of hypoxia on ROS generation by individual oxidases and their ability to influence specific redox-controlled signaling mechanisms in subcellular regions is potentially a major factor contributing to the controversy in the HPV field. For example, contraction and hypoxia have metabolic actions that modulate NADPH/NADP+ and NADH/NAD+ ratios in different subcellular regions.[15] These changes in NAD(P)H redox are likely to be major factors in determining local rates of ROS generation and the impact of oxidant conditions on redox controlled signaling mechanisms regulating vascular function. For example, the generation of increased levels of superoxide by mitochondria under hypoxic conditions is potentially dependent on elevated levels of NADH in this organelle.[15] Increases in cytosolic NADH and NADPH in pulmonary arteries under hypoxia [14] could also be a factor in enhancing Nox oxidase activities or in regulating redox controlled processes under hypoxia. Thus, while there seems to be redundancy in mechanisms potentially contributing to the HPV response, the most physiologically relevant conditions are likely to determine the processes involved. Other mechanisms that have been identified may have roles in adaptation and remodeling (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A schematic hypothesizing how pulmonary arterial acute hypoxia sensing mechanisms may participate in activating changes that contribute to chronic hypoxia-evoked pulmonary hypertension. Cellular NADPH redox and ROS controlled by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and NADPH oxidase (NOX) or mitochondria (mito) are increased by acute and chronic hypoxia. Additionally, nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-derived nitric oxide (NO) has been reported to decrease, potentially lowering PKG activity. In contrast, vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) calcium, Rho kinase and HIF are increased. These changes collectively increase vasoconstriction and decrease contractile phenotype proteins thereby evoking smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, which remodels the pulmonary artery.

The relatively hypoxic and low pressure environment normally seen by pulmonary arteries compared to systemic arteries may create adaptations that contribute to the different responses to hypoxia in these vascular segments. Differences in mitochondria between rat pulmonary and renal arteries potentially influence the dissimilar effects of hypoxia on ROS production observed in these vessel segments.[13] Elevated levels of NADPH and G6PD in pulmonary arteries compared to systemic arteries[17] may be one key difference which creates distinctive redox responses to hypoxia in these vascular segments. For example, increased expression of G6PD and its generation NADPH in pulmonary arteries may help maintain elevated levels of peroxide generation by Nox oxidases[17] and prevent hypoxia from promoting cytosolic NADPH oxidation seen in coronary arteries.[18]

Oxygen Sensors in Systemic Arteries and Metabolic Mechanisms Controlling Blood Flow

Metabolic regulation optimizes the delivery of oxygen by increasing blood flow in systemic circulations to meet the needs of tissue oxygen consumption. Multiple cell types potentially participate in what seem to be redundant mechanisms contributing to the metabolic control of blood flow. Metabolites produced by the tissues being perfused such as adenosine, lactate, carbon dioxide and ROS are potential contributors to the metabolic regulation of blood flow.[19,20] In addition, systemic arterial smooth muscle seems to have redox-regulated signaling mechanisms which promote vasodilation on exposure to hypoxia.[12,13,18] Since the biosynthesis of some autacoids including nitric oxide, prostaglandins, cytochrome P450-derived eicosanoids and ROS are oxygen-dependent, these mediators often influence or modulate systemic and pulmonary responses to hypoxia.[20–22]

Early studies documented that hypoxia elicited relaxation of systemic arteries via mechanisms independent of limitations in ATP and phosphocreatine generation needed for force generation.[23] After removal of the effects of endothelium, NO and prostaglandins, it is now well established that most systemic arteries show relaxation when exposed to severe hypoxia. While an increase in mitochondrial ROS was observed when rat renal arteries were exposed to hypoxia, this process may not be functioning as the oxygen sensor promoting relaxation in these arteries.[13] Our studies suggest contraction of bovine coronary arteries may reverse the effects of hypoxia from an increase to a decrease in mitochondrial superoxide.[15,16] There appears to be a prominent ROS-independent mechanism through which hypoxia can relax systemic arteries.[18] A contributing factor to how hypoxia promotes relaxation may be through inhibiting Rho kinase, a redox regulated system that normally functions to enhance the actions of intracellular calcium on force generation by the contractile apparatus.[24] Our studies in bovine coronary arteries detected that hypoxia promoted relaxation under conditions where it elicited cytosolic NADPH oxidation, a process that appears to coordinate multiple mechanisms of lowering intracellular calcium and opening K+ channels.[11,18] This mechanism seems to originate from a metabolic stress which attenuates a pyruvate-regulated mitochondrial feedback mechanism maintaining glucose-6-phosphate and the generation of NADPH by G6PD.[15,18] Pyruvate has been reported to inhibit functional increases in blood flow,[25] suggesting a potential role of cytosolic NADPH oxidation in metabolic regulation. Interestingly, increasing generation of peroxide from mitochondria (by inhibition of electron transport) or from Nox2 (by TP-prostanoid receptor activation or by stretch) was observed to attenuate hypoxia-induced relaxation of bovine coronary arteries as a result of peroxide stimulating ERK MAP kinase.[16] Thus, elevated peroxide levels could potentially function as an inhibitor of systemic arterial relaxation to hypoxia.

Interactions of Hypertension with Metabolic Regulation

Limited information is available on the effects of hypertension on the metabolic regulation of blood flow. A study by Berne suggests that it can be preserved in a renal model of hypertension.[26] However, hypertension may promote changes in the hypoxia sensing mechanisms that are matching blood flow to the respiratory needs of the tissue. For example, the ability of exercise to increase skeletal muscle blood flow appears to be impaired by hypertension.[27] In addition, a high salt diet has been reported to initially attenuate vasodilator mechanisms associated with metabolic regulation and hypoxia-elicited relaxation of skeletal muscle resistance arteries.[28] Thus, alterations in systemic blood flow regulation by hypoxia may influence the development and progression of hypertension.

Changes in Potential Components of Oxygen Sensing Mechanisms during Systemic and Pulmonary Hypertension

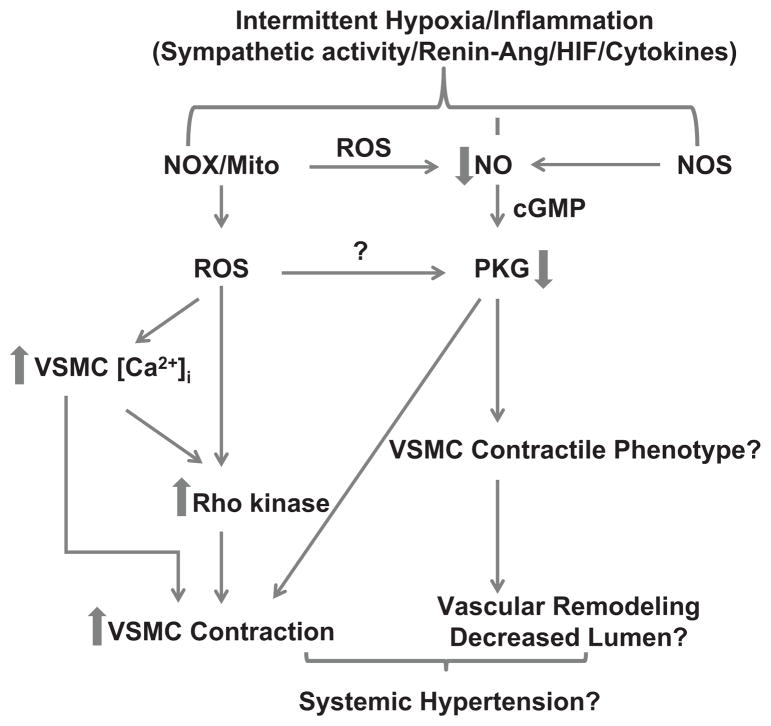

Pulmonary[8,29] and systemic[30,31] hypertension are known to have major effects on many aspects of ROS signaling and systems that are also influenced by hypoxia. Although only limited information is available documenting the effects of pulmonary and systemic hypertension on HPV and metabolic regulation of blood flow,[1,9,21,26,32,33] hypertensive disease processes could potentially have an effect on many of the components of hypoxia sensing mechanisms controlling blood flow. There are many similarities between systemic[31,34] and pulmonary[35] hypertension, such as the roles of increased vasoconstriction, inflammation and remodeling. Substantial evidence exists for changes in the activities of vascular oxidases, mitochondria, NO biosynthesis and ROS metabolizing systems during systemic[31] and/or pulmonary[8] hypertension. For example, a Nox2 deficiency prevents the development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension.[36] In addition, hypertension alters the properties of multiple oxidant-influenced signaling systems regulating vascular function, such as sGC regulation by NO, PKC, rho kinase, systems generating vasoactive eicosanoids and actions controlled by increased levels of hypertension mediators such as angiotensin II and endothelin.[8,31] While many of these systems altered by hypertension are likely to be components of oxygen sensing mechanisms, minimal consideration has been given to the roles of altered oxygen sensors in hypertensive disease processes. The model in Fig. 1 highlights how some of the acute hypoxia sensing mechanisms may participate during chronic hypoxia in activating changes that contribute to the development of pulmonary hypertension. Whereas, the model in Fig. 2 hypothesizes some relationships that could potentially be involved in how chronic hypoxia directly or indirectly influences vascular regulatory mechanisms contributing to changes seen in systemic hypertension. Activation of the HIF systems by hypoxia and/or increased ROS in hypertension appear to have important roles in modulating the expression of many proteins that contribute altered vascular reactivity, metabolic changes and vascular remodeling seen in both systemic and pulmonary hypertension.[37] Interestingly, pulmonary hypertension has been shown to deplete mitochondrial SOD associated activation of HIF-1α under aerobic conditions.[38] This converts pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) to a cancer cell-like metabolic phenotype lacking hypoxic regulation of potassium channels by mitochondrial ROS.[38] Thus, alterations in oxygen sensing mechanisms can regulate multiple processes contributing to the progression of hypertension.

Fig. 2.

Potential mechanisms involved in hypoxia-induced systemic hypertension. Increased NADPH oxidase (NOX)- and mitochondria (mito)-derived ROS stimulated by intermittent decreases in pO2 in multiple systems is speculated to be associated with sleep apnea in humans. Placental hypoxia-induced ROS generation also appears to promote preeclampsia. Increases in vascular smooth muscle calcium and activation of Rho kinase by various factors and cytokines released during hypoxia could be a common pathway leading to vasoconstriction and hypertension. Additionally, we speculate loss of NO derived from NOS leading to decreased activation of PKG may influence vascular smooth muscle contractile phenotype protein expression and remodeling which contribute to increases in systemic blood pressure.

Vascular Remodeling in Hypertension

High blood pressure is known to increase shear stress on the vessel wall, damage endothelium and impair endothelial function. Increased shear stress and pressure elicits ROS generation in the endothelium and underlying vascular smooth muscle cells leading to remodeling of arteries in systemic as well as pulmonary hypertension.[31] During remodeling smooth muscle cells are dedifferentiated and they start to proliferate and/or migrate. Smooth muscle contractile proteins are regulated by transcription factor SRF and cofactors, myocardin and KLF-4.[39,40] In differentiated states smooth muscle expresses myocardin, which elevates the expression of contractile proteins, and during dedifferentiation cell cycle proteins are over-expressed.

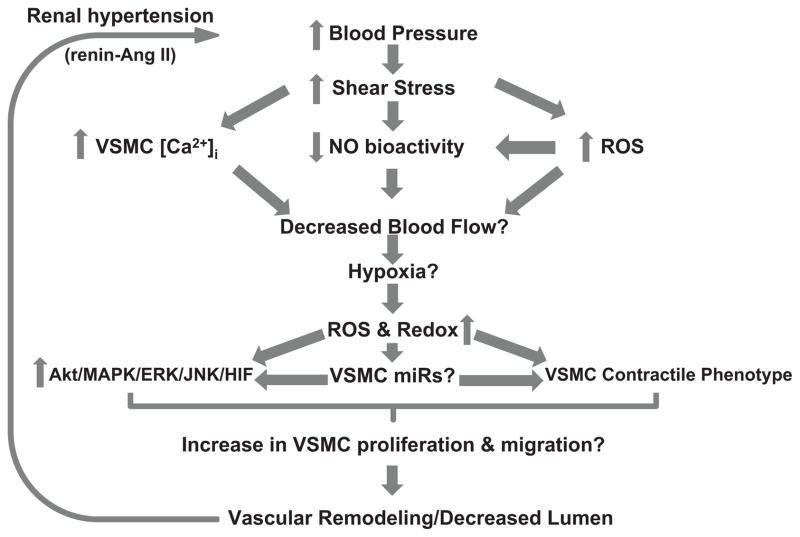

Hypoxia-evokes changes in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells phenotypes. Isolated fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells show a myocardin-SRF-mediated expression of contractile proteins,[41] which is a process driven by PKG.[42] Pulmonary arteries exposed to hypoxia appear to show a similar myocardin-SRF-response.[43] The effects of hypoxia on PKG-dependent myocardin signaling in systemic arteries remains to be defined. Moreover, myocardin and SRF levels seem to be controlled by NFATc signaling, associated with a rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and increased Nox4-derived H2O2.[44,45] Therefore, high intracellular Ca2+ levels and ROS formation associated with hypertension could potentially control excitation-transcription coupling and plasticity of smooth muscle cells. Moreover, myocardin levels are also regulated by miR-143/145 and miR-221.[46,47] miR-145 expression is up-regulated by TGFs,[48] which increases Nox4-derived ROS via smad signaling in systemic arteries.[49] In contrast, miR221 is increased in PASMCs by platelet-derived growth factor stimuli, which promotes Nox-derived ROS production and down-regulation of myocardin in PASMCs.[47] Therefore, one could hypothesize that the balance between NFATc and myocardin signaling is shifted from normal levels by Ca2+ and alterations in ROS, evoking aberrant transcription of genes including miRNAs, promoting medial and intimal thickening remodeling of arteries. This will result in stiffing of the arterial wall and reduction in luminal diameter, which could create hypoxic conditions by decreasing organ blood flow. The model in Fig. 3 highlights how conditions seen in hypertension can promote hypoxia which activates regulatory processes that potentially contribute to the progression of hypertension.

Fig. 3.

A hypothetical model illustrating interrelations between hypertension and hypoxia. Potential cause-effect relationships between increases in blood pressure and impaired blood flow may cause vasoconstriction and hypoxia-like conditions in distal organs controlling blood pressure such as the kidney. Hypoxia has been shown to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) and redox potential. It is hypothesized that this could potentially increase activity of various kinases involved in cell proliferation and migration, modulate miR synthesis that control mitotic kinases expression and angiogenesis, and decrease smooth muscle contractile phenotype protein expression. All of which remodel blood vessels, further increasing blood pressure, promoting hypertension progression.

New evidence suggest that hypoxia-induced decreases in miR-204 is a cause of pulmonary hypertension.[50] Intriguingly, dehydroepiandrosterone partly blocks down-regulation of miR-204 and reduces hypertension.[51] Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits G6PD, and it decreases HPV and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension through mechanisms that may involve NADPH oxidation and/or increased cGMP signaling.[1,52] Thus, miRNAs may contribute to hypoxia-driven redox transcriptional regulation of multiple proteins and cellular processes in hypertension. Furthermore, hypoxia also appears to stabilize HIF-1α in endothelial cells by increasing miR-424, during remodeling-associated angiogenesis.[53] It is possible that smooth muscle cell remodeling controlled by miR-204 may also modulate redox signaling in a manner like miRNAs involved in angiogenesis.[54] Interestingly, knock down of dicer proteins involved in the synthesis of miRNAs, is associated with decreases ROS production by decreasing p47phox.[55] In contrast, Argonaut, another enzyme involved in miRNA processing, is regulated by a ROS-sensitive p38MAPK kinase pathway.[56] Although the previously mentioned signaling pathways activated by either increased blood pressure or hypoxia are rather complicated, as illustrated (Fig. 3), it is likely that there are cause-and-effect relationships between hypertension and hypoxia that need to be explored in future studies.

Roles for localized effects of hypoxia on integrated mechanisms promoting hypertension

Secondary or renal hypertension elicited renal dysfunction is an important contributing factor in the progression this disease process. Evidence is emerging that heterogeneity in renal blood flow may result in hypoxia in medullary regions. Factors such as impairment of flow by angiotensin II-induced vasoconstriction, oxidative stress increasing oxygen utilization and arterial-venous oxygen shunting may increase the extent of hypoxia, and this may contribute to renal dysfunction and the progression of hypertension,[57] through mechanisms highlighted in Fig. 3. For example, hypoxia could further production of angiotensin, aldosterone, endothelin-1 and vasoconstrictive prostanoids. These hormones and autacoids are well known stimulators of Nox oxidases, and they have the capacity to induce gene expression via redox-sensitive AKT kinase, MAP kinase, ERK kinase and JNK kinase signaling pathways which potentially contribute to elevated blood pressure levels.

Preeclampsia is thought to be caused by a shallowly implanted placenta that becomes hypoxic leading to secretion of inflammatory mediators from the placenta, which act on the vascular endothelium. Insufficient uteroplacental oxygenation in preeclampsia is responsible for events leading to the clinical manifestations of this disease.[58] In vivo and in vitro models of placental hypoxia reproduce changes seen in preeclampsia.[58] HIF-1α is increased by a fall in PO2, and this appears to contribute to the pathogenesis of both preeclampsia and intra-uterine growth retardation.[59] It was proposed that placental hypoxia releases cytotoxic factors produced at the maternal-fetal interface into the circulation to manifest the maternal symptoms associated with preeclampsia.[60] Prolonged placental hypoxia or intermittent hypoxia leads to a perpetual cycle of compartmentalized uteroplacental tissue damage, release of anti-angiogenic and vasoconstrictive factors that impair trophoblast invasion and promote systemic vascular resistance resulting in the maternal syndrome via the increased release of soluble flt1 and endoglin.[60] These soluble receptors bind VEGF, PDGF and TGFβ1&3 in the maternal circulation, evoking oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction.[61]

Sleep apnea (SA) is characterized by repeated brief episodes of hypoxia and reoxygenation which originate from causes including obesity, airway obstruction and central nervous system dysfunction.[62] Chronic SA evokes systemic and pulmonary hypertension. Chronic peripheral chemoreflex activation occurring during SA is potentially an important risk factor for hypertension, and the central coupling of respiratory and sympathetic activities has been proposed as a novel mechanism underlying the development of neurogenic hypertension.[63] SA-induced intermittent hypoxia activates the renin-angiotensin system and increases the levels of endothelin-1, C-reactive protein, IL-6, NF-κB, TNF-α, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin in blood.[64] It also increases xanthine oxidase expression and lipid peroxidation. This indicates inflammation and oxidative stress are promoted by intermittent hypoxia in SA. Inflammatory cytokines and renin-angiotensin promote ROS production, which often evokes endothelial dysfunction in SA patients that resolves with continuous positive airway pressure treatment.[65] There is evidence for NADPH oxidase activation in multiple brain regions associated with oxidative brain injury and hypersomnolence in a murine model of SA.[66] Therefore, increased nervous system oxidative stress could be a key factor in increasing sympathetic tone and peripheral resistance. There is also evidence increased vascular NADPH oxidase-derived ROS and decreases in NO synthesis or bio-availability in SA.[67] These changes can potentially mediate constriction of systemic arteries and the development of hypertension.

Concluding Remarks

Hypoxia or cycles of hypoxia and reoxygenation can contribute to the development of some forms of pulmonary and systemic hypertension through processes that appear to involve activation of oxygen sensors often associated with changes in oxidant signaling in various cells in the vasculature and other organ systems. Hypertension may also influence multiple aspects of hypoxia sensing mechanisms promoting hypoxia and other processes which may be important factors in the progression of hypertensive disease process. However, the majority of mechanisms involved in these processes are poorly understood and remain to be defined.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New

Roles for hypoxia in hypertensive disease processes are poorly understood. This review considers interactions between processes involved in sensing hypoxia and systems contributing to systemic and pulmonary hypertension progression.

What Is Relevant

Many pathological conditions like preeclampsia, sleep apnea, high altitude sickness and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that cause intermittent or chronic hypoxia are associated with systemic and/or pulmonary hypertension development.

Summary

Hypertensive disease processes could have effects on many of the components of hypoxia sensing mechanisms thought to be participating in the control of blood flow, which may also influence the progression of hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Our studies were supported by NIH grants HL085352 (SAG), and HL031069, HL043023 and HL066331 (MSW).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

None

References

- 1.Gupte SA, Wolin MS. Oxidant and redox signaling in vascular oxygen sensing: implications for systemic and pulmonary hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1137–1152. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bärtsch P, Gibbs JSR. Effect of altitude on the heart and the lungs. Circulation. 2007;116:2191–2202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.650796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaouat A, Naeije R, Weitzenblum E. Pulmonary hypertension in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1371–1385. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna JM. Climate, altitude and blood pressure. Hum Biol. 1999;71:553–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prewitt RL, Cardoso SS, Wood WB. Prevention of arteriolar rarefaction in the spontaneously hypertensive rat by exposure to simulated high altitude. J Hypertens. 1986;4:735–740. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tripathy V, Gupta R. Blood pressure variation among Tibetans at different altitudes. Ann Human Biol. 2007;34:470–483. doi: 10.1080/03014460701412284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiori G, Facchini F, Pettener D, Rimondi A, Battistini N, Bedogni G. Relationships between blood pressure, anthropometric characteristics and blood lipids in high- and low-altitude populations from Central Asia. Ann Hum Biol. 2000;27:19–28. doi: 10.1080/030144600282343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrell NW, Adnot S, Archer SL, Dupuis J, Jones PL, MacLean MR, McMurtry IF, Stenmark KR, Thistlethwaite PA, Weissmann N, Yuan JX, Weir EK. Cellular and molecular basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;4:S20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sylvester JT, Shimoda LA, Aaronson PI, Ward JPT. Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:367–520. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stasch J-P, Pacher P, Evgenov OV. Soluble guanylate cyclase as an emerging therapeutic target in cardiopulmonary disease. Circulation. 2011;123:2263–2273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.981738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neo BH, Kandhi S, Ahmad M, Wolin MS. Redox regulation of guanylate cyclase and protein kinase G in vascular responses to hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waypa GB, Schumacker PT. Hypoxia-induced changes in pulmonary and systemic vascular resistance: where is the O2 sensor? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weir EK, Archer SL. The role of redox changes in oxygen sensing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupte RS, Rawat DK, Chettimada S, Cioffi DL, Wolin MS, Gerthoffer WT, McMurtry IF, Gupte SA. Activation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase promotes acute hypoxic pulmonary artery contraction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19561–19571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Q, Wolin MS. Effects of hypoxia on relationships between cytosolic and mitochondrial NAD(P)H redox and superoxide generation in coronary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H978–H989. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00316.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Q, Zhao X, Ahmad M, Wolin MS. Mitochondrial-derived hydrogen peroxide inhibits relaxation of bovine coronary arterial smooth muscle to hypoxia through stimulation of ERK MAP kinase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H2262–2269. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00817.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupte SA, Kaminski PM, Floyd B, Agarwal R, Ali N, Ahmad M, Edwards J, Wolin MS. Cytosolic NADPH may regulate differences in basal Nox oxidase-derived superoxide generation in bovine coronary and pulmonary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H13–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00629.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupte SA, Wolin MS. Hypoxia promotes relaxation of bovine coronary arteries through lowering cytosolic NADPH. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2228–2238. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00615.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deussen A, Brand M, Pexa A, Weichsel J. Metabolic coronary flow regulation-- current concepts. Basic Res Cardiol. 2006;101:453–464. doi: 10.1007/s00395-006-0621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Regulation of coronary blood flow during exercise. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1009–1086. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weissmann N, Nollen M, Gerigk B, Ghofrani HA, Schermuly RT, Gunther A, Quanz K, Fink L, Hanze J, Rose F, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Downregulation of hypoxic vasoconstriction by chronic hypoxia in rabbits: effects of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H931–938. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00376.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupte SA, Zias EA, Sarabu MR, Wolin MS. Role of prostaglandins in mediating differences in human internal mammary and radial artery relaxation elicited by hypoxia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:510–518. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coburn RF, Moreland S, Moreland RS, Baron CB. Rate-limiting energy-dependent steps controlling oxidative metabolism-contraction coupling in rabbit aorta. J Physiol. 1992;448:473–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorne GD, Ishida Y, Paul RJ. Hypoxic vasorelaxation: Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent mechanisms. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasuo I, Katherine C, Williamson JR. NADH augments blood flow in physiologically activated retina and visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:653–658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307458100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ely SW, Sun CW, Knabb RM, Gidday JM, Rubio R, Berne RM. Adenosine and metabolic regulation of coronary blood flow in dogs with renal hypertension. Hypertension. 1983;5:943–950. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.5.6.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyberg M, Jensen LG, Thaning P, Hellsten Y, Mortensen SP. Role of nitric oxide and prostanoids in the regulation of leg blood flow and blood pressure in humans with essential hypertension: effect of high-intensity aerobic training. J Physiol. 2012;590:1481–1494. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber DS, Lombard JH. Elevated salt intake impairs dilation of rat skeletal muscle resistance arteries via ANG II suppression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H500–H506. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humbert M, Morrell NW, Archer SL, Stenmark KR, MacLean MR, Lang IM, Christman BW, Weir EK, Eickelberg O, Voelkel NF, Rabinovitch M. Cellular and molecular pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:13S–24S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feletou M, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelial dysfunction: a multifaceted disorder (The Wiggers Award Lecture) Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;91:H985–1002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00292.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paravicini TM, Touyz RM. Redox signaling in hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weissmann N, Nollen M, Gerigk B, Ghofrani HA, Schermuly RT, Gunther A, Quanz K, Fink L, Hanze J, Rose F, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Downregulation of hypoxic vasoconstriction by chronic hypoxia in rabbits: effects of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H931–938. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00376.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guazzi MD, Alimento M, Berti M, Fiorentini C, Galli C, Tamborini G. Enhanced hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in hypertension. Circulation. 1989;79:337–343. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A, Weyand CM. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:132–140. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassoun PM, Mouthon L, Barbera JA, Eddahibi S, Flores SC, Grimminger F, Jones PL, Maitland ML, Michelakis ED, Morrell NW, Newman JH, Rabinovitch M, Schermuly R, Stenmark KR, Voelkel NF, Yuan JX, Humbert M. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Zelko I, Erbynn E, Sham J, Folz R. Hypoxic pulmonary hypertension: Role of superoxide and nadph oxidase (gp91phox) Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L2–10. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00135.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell. 2012;148:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Archer SL, Gomberg-Maitland M, Maitland ML, Rich S, Garcia JGN, Weir EK. Mitochondrial metabolism, redox signaling, and fusion: a mitochondria-ROS-HIF-1α-Kv1.5 O2-sensing pathway at the intersection of pulmonary hypertension and cancer. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H570–H578. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01324.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexanderm MR, Owens GK. Epigenetic Control of Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation and Phenotypic Switching in Vascular Development and Disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:13–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Sinha S, McDonald OG, Shang Y, Hoofnagle MH, Owens GK. Kruppel-like factor 4 abrogates myocardin-induced activation of smooth muscle gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9719–9727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou W, Negash S, Liu J, Raj JU. Modulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype in hypoxia: role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase and myocardin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L780–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90295.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi C, Sellak H, Brown FM, Lincoln TM. cGMP-dependent protein kinase and the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell gene expression: possible involvement of Elk-1 sumoylation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1660–1670. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00677.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chettimada S, Rawat DK, Dey N, Kobelja R, Simms Z, Wolin MS, Lincoln TM, Gupte SA. Glc-6-PDH and PKG contribute to hypoxia-induced decrease in contractile phenotype proteins and pulmonary artery contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00002.2012. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wamhoff BR, Bowles DK, Owens GK. Excitation-transcription coupling in arterial smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2006;98:868–78. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216596.73005.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao Q, Luo Z, Pepe AE, Margaritti A, Zeng L, Xu Q. Embryonic stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells is mediated by Nox4-produced H2O2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C711–723. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00442.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, Berry EC, Morton SU, Muth AN, Lee TH, Miano JM, Ivey KN, Srivastava D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460:705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Nguyen PH, Lagna G, Hata A. Induction of microRNA-221 by platelet-derived growth factor signaling is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3728–3738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long X, Miano JM. Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) utilizes distinct pathways for the transcriptional activation of microRNA 143/145 in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30119–30129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cucoranu I, Clempus R, Dikalova A, Phelan PJ, Ariyan S, Dikalov S, Sorescu D. NAD(P)H oxidase 4 mediates transforming growth factor-beta1-induced differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Circ Res. 2005;97:900–907. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000187457.24338.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Courboulin A, Paulin R, Giguère NJ, Saksouk N, Perreault T, Meloche J, Paquet ER, Biardel S, Provencher S, Côté J, Simard MJ, Bonnet S. Role for miR-204 in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Exp Med. 2011;208:535–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paulin R, Meloche J, Jacob MH, Bisserier M, Courboulin A, Bonnet S. Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits the Src/STAT3 constitutive activation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1798–809. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00654.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oka M, Karoor V, Homma N, Nagaoka T, Sakao E, Golembeski SM, Limbird J, Imamura M, Gebb SA, Fagan KA, McMurtry IF. Dehydroepiandrosterone upregulates soluble guanylate cyclase and inhibits hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghosh G, Subramanian IV, Adhikari N, Zhang X, Joshi HP, Basi D, Chandrashekhar YS, Hall JL, Roy S, Zeng Y, Ramakrishnan S. Hypoxia-induced microRNA-424 expression in human endothelial cells regulates HIF-α isoforms and promotes angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4141–4154. doi: 10.1172/JCI42980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Khanna S, Roy S. Micromanaging vascular biology: tiny microRNAs play big band. J Vasc Res. 2009;46:527–540. doi: 10.1159/000226221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shilo S, Roy S, Khanna S, Sen CK. Evidence for the involvement of miRNA in redox regulated angiogenic response of human microvascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:471–477. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ufer C, Wang CC, Borchert A, Heydeck D, Kuhn H. Redox control in mammalian embryo development. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:833–875. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palm F, Nordquist L. Renal oxidative stress, oxygenation and hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R229–R241. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00720.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rolfo A, Many A, Racano A, Tal R, Tagliaferro A, Ietta F, Wang J, Post M, Caniggia I. Abnormalities in oxygen sensing define early and late onset preeclampsia as distinct pathologies. PLoS One. 2011;5:e13288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tal R, Shaish A, Barshack I, Polak-Charcon S, Afek A, Volkov A, Feldman B, Avivi C, Harats D. Effects of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha overexpression in pregnant mice: possible implications for preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2011;177:2950–2962. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma S, Norris WE, Kalkunte S. Beyond the threshold: an etiological bridge between hypoxia and immunity in preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;85:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lorquet S, Pequeux C, Munaut C, Foidart JM. Aetiology and physiopathology of preeclampsia and related forms. Acta Clin Belg. 2011;65:237–241. doi: 10.1179/acb.2010.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dempsey JA, Veasley SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zoccal DB, Machado BH. Coupling between respiratory and sympathetic activities as a novel mechanism underpinning neurogenic hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramar K, Caples SM. Vascular changes, cardiovascular disease and obstructive sleep apnea. Future Cardiol. 2011;7:241–249. doi: 10.2217/fca.10.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Monahan K, Redline S. Role of obstructive sleep apnea in cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:541–547. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32834b806a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhan G, Serrano F, Fenik P, Hsu R, Kong L, Pratico D, Klann E, Veasey SC. NADPH oxidase mediates hypersomnolence and brain oxidative injury in a murine model of sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:921–929. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-581OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tahawi Z, Orolinova N, Joshua IG, Bader M, Fletcher EC. Altered vascular reactivity in arterioles of chronic intermittent hypoxic rats. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2007–2013. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]