R1 mapping after labeling monocytes with T1-shortening gadolinium-labeled liposomes enables the in vivo measurement of monocyte and/or macrophage spatiotemporal kinetics after myocardial infarction.

Abstract

Purpose:

To test the hypothesis that magnetic resonance (MR) imaging R1 (R1 = 1/T1) mapping after selectively labeling monocytes with a T1-shortening contrast agent in vivo would enable the quantitative measurement of their spatiotemporal kinetics in the setting of infarct healing.

Materials and Methods:

All procedures were performed in mice and were approved by the institutional committee on animal research. One hundred microliters of dual-labeled liposomes (DLLs) containing gadolinium (Gd)-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)-bis(stearylamide) and DiI dye were used to label monocytes 2 days before myocardial infarction (MI). MI was induced by occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery for 1 hour, followed by reperfusion. MR imaging R1 mapping of mouse hearts was performed at baseline on day −3, on day 0 before MI, and on days 1, 4, and 7 after MI. Mice without labeling were used as controls. ΔR1 was calculated as the difference in R1 between mice with labeling and those without labeling. CD68 immunohistochemistry and DiI fluorescence microscopy were used to confirm that labeled monocytes and/or macrophages infiltrated the postinfarct myocardium. Statistical analysis was performed by using two-way analysis of variance and the unpaired two-sample t test.

Results:

Infarct zone ΔR1 was slightly but nonsignificantly increased on day 1, maximum on day 4 (P < .05 vs all other days), and started to decrease by day 7 (P < .05 vs days −3, 0, and 1) after MI, closely reflecting the time course of monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration of the infarcted myocardium shown by prior histologic studies. Histologic results confirmed the presence and location of DLL-labeled monocytes and/or macrophages in the infarct zone on day 4 after MI.

Conclusion:

R1 mapping after labeling monocytes with T1-shortening DLLs enables the measurement of post-MI monocyte and/or macrophage spatiotemporal kinetics.

© RSNA, 2012

Supplemental material: http://radiology.rsna.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1148/radiol.12111863/-/DC1

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains a leading cause of heart failure and mortality in Western societies. At the tissue level, the acute MI event is followed by a multistep healing process that is initiated by the immune system (1,2). After prolonged ischemia, cell necrosis (or apoptosis) occurs, activating the complement and cytokine cascades and leading to the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the infarcted myocardium. On reaching the infarcted tissue, monocytes differentiate into macrophages, which play a number of critical roles in infarct healing. Namely, monocytes and/or macrophages clear necrotic debris, degrade the extracellular matrix, and secrete chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors that promote fibroblast proliferation and angiogenesis (3). Myofibroblasts generate collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins and contribute heavily to scar formation. This sequence of events plays a major role in determining the macroscopic structure and geometry of the scar, and more generally plays a critical role in constraining infarct expansion early after MI. Consequently, these processes have a substantial impact on long-term post-MI left ventricular (LV) remodeling and the progression to heart failure. Given the central role of monocytes and/or macrophages in infarct healing and their potential as therapeutic targets (4–6), we sought to develop MR imaging methods to quantify their tissue density and spatiotemporal kinetics after MI.

In vivo labeling and imaging of monocytes and/or macrophages in MI has been investigated previously (7–12); however, these studies did not successfully quantify monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration of and depletion from the infarct zone. The most common approach has been to label monocytes and/or macrophages by using iron oxide particles and to detect the labeled cells by using T2*-weighted MR imaging (9–12). However, iron oxide particles induce spin dephasing and T2* shortening, producing signal loss and negative contrast. Because other effects (eg, local magnetic field gradients due to differences in magnetic susceptibility) also cause negative contrast, T2* shortening agents have the disadvantage that they create a nonunique signature. Furthermore, iron oxide particles have been shown to persist in the infarct zone long after the depletion of monocytes and/or macrophages (11,12). Thus, iron oxide particles are not always colocalized with monocytes and/or macrophages, which is a major limitation.

The purpose of the present study was to test the hypothesis that MR imaging R1 (R1 = 1/ T1) mapping after selectively labeling monocytes with a T1-shortening contrast agent in vivo would enable the quantitative measurement of their spatiotemporal kinetics in the setting of infarct healing.

Materials and Methods

Our overall approach was to use a mouse model of reperfused MI, paramagnetic liposomes for labeling monocytes, and MR imaging R1 mapping to achieve quantitative measurements. Liposomes were dual labeled with gadolinium for in vivo detection at MR imaging and DiI for ex vivo detection with fluorescence microscopy. Monocytes were labeled in vivo by using a single intravenous injection of liposomes, and serial R1 mapping was used to detect labeled cells at various time points. The in vivo MR imaging results were validated by using fluorescence microscopy and immunohistochemistry to detect liposomes and monocytes and/or macrophages, respectively.

Animal Model

All animal studies were performed under protocols that complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (13) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at our institution. MI was induced in mice by means of a 1-hour occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery followed by reperfusion (Y.X., with 10 years of experience). The details of the surgery have been previously described (14).

Liposomes

Dual-labeled liposomes (DLLs) containing gadolinium (Gd)-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)-bis(stearylamide) (15) (7 mol%, Chemir Analytical Services, Maryland Heights, Mo) and DiI dye (0.2 mol%, Molecular Probes) were prepared by a slightly modified reverse phase evaporation procedure (16,17) (A.L.K., with 32 years of experience). Liposomes contained cholesterol (in an approximately 1:1 ratio with phosphatidylcholine) to improve stability in blood (18); a large size was selected for enhanced spleen uptake (19). The mean size of the liposomes was found to be 0.5 ± 0.25 μm, as determined by dynamic light scattering. The longitudinal relaxivity (r1) of the liposomes was determined at Look-Locker MR imaging to be 3.8 mmol−1 ⋅ sec−1. The circulation half-life of the liposomes was found to be 90 minutes, as determined by MR imaging R1 measurements in the LV blood pool.

Experimental Protocol

A total of 24 wild-type male C57Bl/6 mice (9–10 weeks old; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Me) were used, and of those, 20 underwent MI surgery. Prior histologic work in mice showed that the number of monocytes and/or macrophages in the infarct zone starts to increase 1–2 days after MI, reaches a maximum on day 4 after MI, and decreases thereafter from days 7–28 after MI (20,21). On the basis of these data, the timeline of our experiment was designed (Fig E1 [online]) (all authors). The animals were divided into four groups. In the first group (n = 8), 100 μL DLL was injected intravenously two days before MI to prelabel monocytes and to allow sufficient time for the DLL to clear from the blood. Reperfused MI was induced on day 0. Imaging was performed on days −3 (3 days before MI), 1, 4, and/or 7 after MI. Day 0 MR imaging was performed in the second group of mice (n = 4), which were also injected with DLL on day −2 but which did not undergo surgery. This was done to acquire R1 data after more than 99% of the contrast agent washed out of the blood pool and prior to the induction of MI. The first and the second groups together formed the labeled group of mice. Control MR imaging data were acquired from the third group of mice that was not injected with DLL (n = 9), because infarct-related edema and subsequently R1 change with time after MI (22). For this group, the reperfused MI procedure was performed on day 0 and MR imaging was performed on days −3, 0, 1, 4, and/or 7. This group was denoted the unlabeled control group. The fourth group of mice (n = 3) was used for histologic examination on day 4 after MI. These mice also received intravenous injections of 100 μL DLL on day −2, underwent MI surgery on day 0, and underwent MR imaging on day 4 after MI. Some mice were imaged at all intended time points, but other mice did not tolerate repeated anesthesia and imaging sessions.

MR Imaging

MR imaging was performed with a 7.0-T Clinscan system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) by using a 30-mm-diameter birdcage radiofrequency coil (N.K.N., with 3 years of experience). Mice were positioned prone in the imaging unit, body temperature was maintained at 36°C ± 0.5 by using thermostated water, and anesthesia was maintained at 1.25% during imaging. Electrocardiographic data, body temperature, and respiration were monitored during imaging by using an MR imaging–compatible system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY).

Localizer cine imaging was performed to select a midventricular short-axis section containing a substantial region of infarcted myocardium (affecting one-quarter to three-quarters of the circumference, as evidenced by reduced wall thickening). A cardiorespiratory gated Look-Locker pulse sequence was used for R1 mapping (23) (M.H.V., with 6 years of experience). The imaging parameters included a repetition time (time between inversion pulses) of 8 seconds, an echo time of 0.67 msec, a field of view of 35 × 35 mm2, a matrix of 128 × 128, a section thickness of 1 mm, a flip angle of 3°, three averages, 87 spiral interleaves, and 65–80 sampled inversion times. The 3° flip angle was selected to minimize perturbations to the longitudinal magnetization during T1 relaxation. The total imaging time for this sequence was approximately 45 minutes, depending on heart rate. Cine displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) imaging (24) was performed to assess myocardial strain in a matched section location, and the deficit in circumferential strain was used to delineate the infarct zone because of concerns that the introduction of gadopentetate dimeglumine used for late gadolinium-enhanced imaging might interfere with the quantitation of DLL at a future time point.

Histologic Examination

Three mice underwent immunohistochemical examination for the CD68 antigen (a monocyte and/or macrophage marker) performed by using a rat antimouse CD68 monoclonal antibody (clone FA-11; BioLegend, San Diego, Calif) and fluorescence microscopy for DiI (Y.X. and B.A.F., with 10 and 20 years of experience, respectively).

Data Analysis

Cine DENSE and Look-Locker images were exported to a workstation for analysis (N.K.N. and F.H.E., with 3 and 20 years of experience, respectively) by using custom-written programs developed in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, Mass). For cine DENSE images, circumferential strain (Ecc) was calculated (25). A marked deficit in circumferential strain (Ecc greater than −0.06) was used to define the infarct zone (26,27). Myocardial R1 was calculated by using a least-squares fit to a Bloch equation T1-relaxation curve. Maps of myocardial R1 were calculated pixel-by-pixel and were filtered by using a mean crescent filter with a kernel of 2 pixels in the radial direction and 7 pixels in the circumferential direction (23). Filtering was used to smooth the R1 maps and to reduce noise.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of R1 measurements was performed by using SigmaStat (Systat Software, Point Richmond, Calif) with two-way analysis of variance assuming compound symmetry (N.K.N. and F.H.E.). Unpaired two-sample t tests were used for statistical analysis of ΔR1 measurements. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All R1 values in the text and graphs are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean. ΔR1 values in the graph are presented as means with 95% confidence intervals. All values in the graphs were normally distributed.

Results

MR Imaging

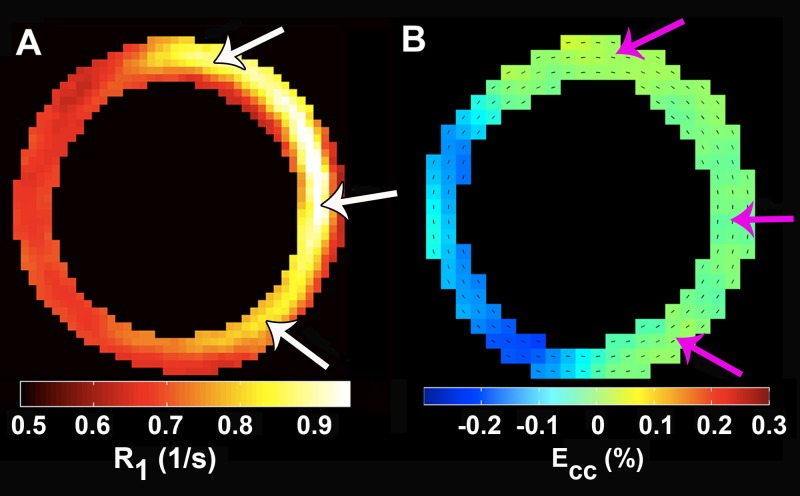

Sample images demonstrating T1 relaxation of the heart acquired by using the Look-Locker pulse sequence are shown in Figure E2 (online). These images were acquired 4 days after MI in a mouse that received DLL on day −2. The large region of infarction (anterior, lateral, and inferior walls in Fig E2, D [online], white arrows) demonstrates substantial T1 shortening compared with the noninfarcted septum. T1 shortening in this region is attributed to the phagocytosis of DLL by monocytes that occurred before MI surgery and the subsequent migration of these cells to the injured myocardium. Representative T1 relaxation measurements and the corresponding best Bloch equation fits for the infarcted and remote myocardium of a DLL-labeled mouse are shown in Figure E3 (online). Also shown in this figure are the results for the infarcted myocardium of a mouse without labeling at day 4 after MI. In this figure, the signal intensities are normalized to the equilibrium signal intensity. The T1 of the infarcted myocardium of a mouse with labeling (Fig E3 [online], red circles) was reduced compared with that in the remote myocardium (Fig E3 [online], blue circles) because of infiltration of the infarct zone by labeled monocytes and/or macrophages. The T1 of the infarcted myocardium of a mouse without labeling (Fig E3 [online], pink circles) was increased on day 4 after MI because of infarct-related edema. T1 shortening at day 4 after MI in DLL-labeled mice is also evident in an R1 map, as shown in Figure 1, A, (arrows). Spatially, R1 lengthening is confined to the dysfunctional infarct zone, which was defined on cine DENSE images as a deficit in circumferential strain (Fig 1, B, arrows). Also note that the R1 map indicates that monocyte and/or macrophage density is highest in the center of the infarct and decreases toward the infarct border.

Figure 1:

A, Illustrative R1 map from a day 4 post-MI mouse injected with 100 μL DLL on day −2. R1 significantly increased in the infarcted myocardium (arrows), whereas R1 remained largely normal in the remote myocardium. B, The region with increased R1 is colocalized with the region of reduced contractile function, as measured by circumferential strain (arrows).

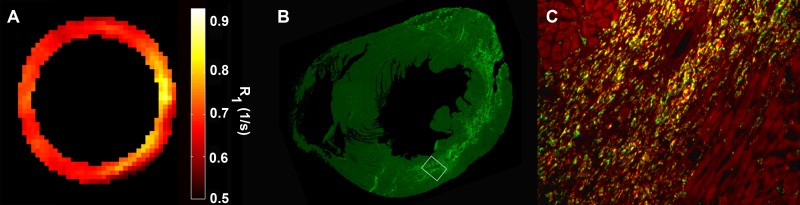

Histologic Examination

Fluorescence microscopy and immunohistochemistry were performed to confirm the presence of DLL-labeled monocytes and/or macrophages in the LV on day 4 after MI. Figure 2, A, shows an example R1 map from a day 4 post-MI mouse injected with 100 μL DLL on day −2. Figure 2, B, shows fluorescence immunohistochemical findings in the same mouse after euthanasia on day 4 after MI. In this image, the CD68-positive monocytes and/or macrophages in the short-axis section are immunolabeled bright green, which distinguishes the monocytes and/or macrophages from the dull green autofluorescing cardiomyocytes. Note that the location of the bright green CD68-positive monocytes and/or macrophages corresponds closely to the region with increased R1 as measured with MR imaging in Figure 2, A. Figure 2, C, is a high-power (×20) magnification of the region bounded by the white box in Figure 2, B, where CD68-positive monocytes and/or macrophages are bright green and DiI-labeled cells are bright red. The monocytes and/or macrophages that are positive for both CD68 (green) and DiI (red) appear yellow. The vast majority of the CD68-positive cells are also DiI-positive (ie, yellow), although there exists a subpopulation of monocytes and/or macrophages (bright green cells) that were not labeled with DiI. The surviving cardiomyocytes bordering the infarct zone are colored dull red because of endogenous autofluorescence.

Figure 2:

A–C, Correspondence between R1 map, CD68-positive monocytes and/or macrophages, and DLL. A, R1 map from a day 4 post-MI mouse injected with 100 μL DLL on day −2. B, Fluorescence immunohistochemistry image shows CD68-positive monocytes and/or macrophages in bright green. C, High-power (×20) magnification of region bounded by white box in, B, shows CD68-positive monocytes and/or macrophages in green and DLL in bright red. Note that monocytes and/or macrophages positive for both CD68 (green) and DLL (red) are yellow.

Spatiotemporal Changes in Myocardial R1

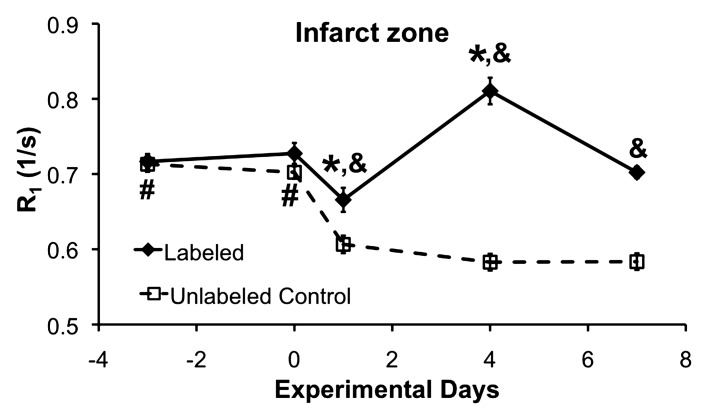

The time courses of R1 in the infarcted myocardium of the DLL-labeled and unlabeled mice are shown in Figure 3. R1 in the infarcted myocardium of labeled mice (Fig 3a, diamonds) increased significantly on day 4 after MI. In unlabeled control mice, R1 decreased significantly on all days after MI (Fig 3a, squares), likely because of post-MI edema. Hence, infarct zone R1 was significantly increased in the labeled mice on all days after MI compared with the unlabeled mice.

Figure 3a:

(a) R1 measurements in the infarct zone of DLL-labeled and unlabeled control mice. In the DLL-labeled mice, infarct zone R1 was reduced on day 1 (* = P < .05 vs all days) because of edema. By day 4, R1 was significantly increased (* = P < .05 vs all days) because of infiltration of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages. In the unlabeled mice, infarct zone R1 was significantly reduced on all days after MI because of edema (# = P < .05 vs all days after MI). As compared with that in the unlabeled mice, infarct zone R1 in the labeled mice was significantly increased on all days after MI (& = P < .05 vs unlabeled mice on the same day) because of the presence of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages. (b) R1 measurements in the remote zone of the labeled and the unlabeled control mice. In the labeled mice, remote zone R1 was significantly reduced on day 7 after MI ($$ = P < .05 vs day 0 and day 1). In the unlabeled mice, R1 was significantly reduced on days 4 and 7 after MI as compared with baseline ($ = P < .05 vs days 4 and 7 after MI) and on all days after MI as compared with day 0 (# = P < .05 vs all days after MI), probably because of edema. Remote zone R1 in the unlabeled mice was reduced on day 4 after MI as compared with day 1 after MI (* = P < .05 vs day 4). Remote zone R1 was significantly increased on days 1 and 4 after MI in the labeled mice as compared with the unlabeled control mice (& = P < .05 vs unlabeled mice on the same day), perhaps reflecting infiltration of the remote zone by a small number of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages. Partial-volume effect at the edges of the infarct zone may also have contributed to the increased R1 measurements in the remote zone of the labeled mice on days 1 and 4 after MI.

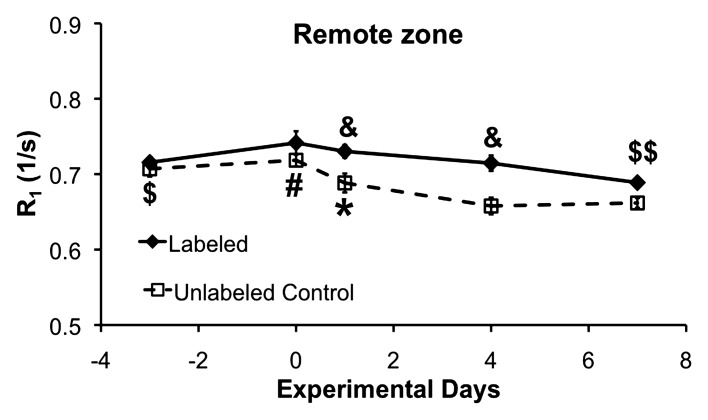

The time courses of R1 in the remote myocardium of the labeled and unlabeled mice are shown in Figure 3b. A small decrease in remote zone R1 was observed in the unlabeled mice on days 4 and 7 after MI compared with baseline and day 0, possibly because of edema. Remote zone R1 in the labeled mice was slightly increased on days 1 and 4 after MI compared with the unlabeled mice, possibly because of low-level monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration of the remote zone or partial-volume effects at the edges of the infarct zone.

Figure 3b:

(a) R1 measurements in the infarct zone of DLL-labeled and unlabeled control mice. In the DLL-labeled mice, infarct zone R1 was reduced on day 1 (* = P < .05 vs all days) because of edema. By day 4, R1 was significantly increased (* = P < .05 vs all days) because of infiltration of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages. In the unlabeled mice, infarct zone R1 was significantly reduced on all days after MI because of edema (# = P < .05 vs all days after MI). As compared with that in the unlabeled mice, infarct zone R1 in the labeled mice was significantly increased on all days after MI (& = P < .05 vs unlabeled mice on the same day) because of the presence of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages. (b) R1 measurements in the remote zone of the labeled and the unlabeled control mice. In the labeled mice, remote zone R1 was significantly reduced on day 7 after MI ($$ = P < .05 vs day 0 and day 1). In the unlabeled mice, R1 was significantly reduced on days 4 and 7 after MI as compared with baseline ($ = P < .05 vs days 4 and 7 after MI) and on all days after MI as compared with day 0 (# = P < .05 vs all days after MI), probably because of edema. Remote zone R1 in the unlabeled mice was reduced on day 4 after MI as compared with day 1 after MI (* = P < .05 vs day 4). Remote zone R1 was significantly increased on days 1 and 4 after MI in the labeled mice as compared with the unlabeled control mice (& = P < .05 vs unlabeled mice on the same day), perhaps reflecting infiltration of the remote zone by a small number of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages. Partial-volume effect at the edges of the infarct zone may also have contributed to the increased R1 measurements in the remote zone of the labeled mice on days 1 and 4 after MI.

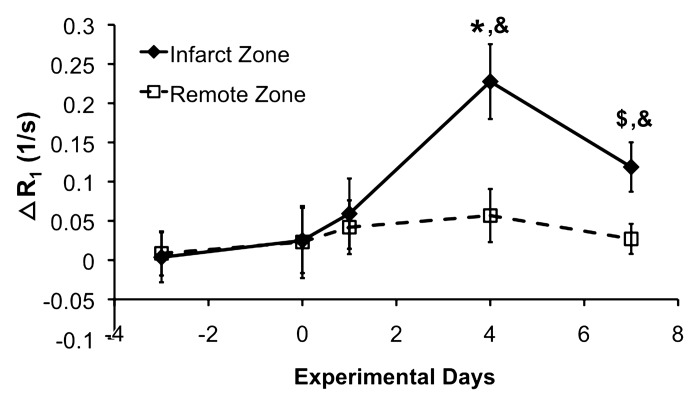

The effect of R1 shortening because of edema on monocyte and/or macrophage detection was corrected by calculating ΔR1. For each time point, ΔR1 was calculated as the difference between the average R1 values of the DLL-labeled mice and those of the unlabeled mice. The time course of ΔR1 in the infarct zone thus reflects the time course of monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration in the infarcted myocardium, as shown in Figure 4. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Infarct zone ΔR1 was slightly but nonsignificantly increased on day 1 after MI in comparison with baseline. This reflected the onset of monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration. Infarct zone ΔR1 was maximum (P < .05 vs all other days) on day 4 after MI, which indicates that labeled monocyte and/or macrophage density was highest on that day. Infarct zone ΔR1 was significantly reduced on day 7 after MI in comparison with day 4; however, it was still significantly elevated in comparison with baseline, day 0, and day 1. The decline on day 7 likely reflects the depletion of monocytes and/or macrophages in the infarct zone. Given these results, the time course of monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration as depicted by ΔR1 is in excellent agreement with results of prior histologic studies (20,21).

Figure 4:

ΔR1 measurements in infarct zone and remote zone. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Infarct zone ΔR1 showed a small nonsignificant increase on day 1 after MI and reached maximal levels on day 4 after MI (* P < .05 vs all other days). Infarct zone ΔR1 was reduced on day 7 after MI in comparison with day 4; however, it was still significantly elevated in comparison with days −3, 0, and 1 ($P < .05 vs days −3, 0, and 1). ΔR1 significantly increased on days 4 and 7 after MI in the infarct zone as compared with the remote zone (&P < .05 vs remote zone on the same day).

Results of R1 mapping of the spleen verified that the DLL contrast agent was successfully and reproducibly injected. These data also suggest that a depot of monocytes remained labeled with DLL through day 7 after MI, as indicated by significantly increased R1 in the spleens of labeled mice compared with that in the spleens of the unlabeled mice on all days after injection (Fig E4 [online]).

Discussion

Monocytes and/or macrophages play an increasingly recognized role in both the degradative and reparative phases of infarct healing, and modulation of the monocyte and/or macrophage response may offer therapeutic benefits for post-MI LV remodeling and heart failure (4,5). The major contribution of this study is the development of MR imaging methods that measure the spatiotemporal kinetics of monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration of the infarct zone after MI. Our approach was to label monocytes in vivo by using T1-shortening DLL prior to inducing MI and to serially quantify monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration by using R1 mapping for 7 days after MI. The resulting time course of ΔR1 in the infarct zone demonstrates post-MI monocyte and/or macrophage kinetics that are in very close agreement with results of prior ex vivo histologic studies that involved counting the number of monocytes and/or macrophages per square millimeter in immunostained tissue slices (20,21).

In the present study, monocytes were labeled 2 days before MI to ensure that signal enhancement and increases in R1 were due to labeled monocytes infiltrating the infarct zone and not due to resident infarct-zone monocytes and/or macrophages endocytosing extravasated DLL from blood. By injecting DLL 2 days before MI, we allowed sufficient time for the liposomes to clear from the blood, as demonstrated by pre-MI imaging on day 0, which revealed no significant difference between myocardial R1 on day 0 and that at baseline on day −3. Because no additional contrast agent was injected after day −2, all enhancement subsequent to day 0 must be due to labeled cells that migrate to and infiltrate the myocardium. Results of prior histologic studies (20,21) have shown that few monocytes and/or macrophages are present in the infarct region on days 1 and 2 after MI. Our day 1 imaging revealed a small but nonsignificant increase in infarct zone ΔR1 as compared with baseline. The heart was also examined on day 4 after MI, because prior histologic studies showed maximum monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration on this day (20,21). Our histologic examination on day 4 confirmed a high density of monocytes and/or macrophages in the infarct zone and verified that the vast majority of DLL-labeled cells in the infarct zone were CD68-positive monocytes and/or macrophages. Consistent with the results of immunohistochemistry, MR imaging showed that infarct-zone ΔR1 was maximum at this time. Prior histologic studies (20,21) have also shown that the number of monocytes and/or macrophages in the infarct zone starts to decrease by day 7 after MI. Thus, MR imaging was also performed on day 7, and parallel results were obtained, showing that infarct zone ΔR1 on day 7 decreased compared with day 4 but still remained elevated compared with other days. In spatial terms, we demonstrated that the monocytes and/or macrophages were confined to the region with reduced strain, and we also observed a gradation of R1 within the infarct zone on day 4 after MI, with R1 being the highest in the core of the infarct zone and decreasing toward the edges of the infarct zone. Although our results do not directly prove that gadolinium colocalizes with the inflammatory cells, the combination of a pre-MI labeling strategy, R1 mapping, and histologic results strongly suggest that our MR imaging methods are revealing the kinetics of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages after MI.

R1 measurements were also made in the spleen, as this organ has recently been shown to be a reservoir of monocytes that infiltrate the post-MI heart (28). R1 measurements of the spleen on day 0 served to verify that DLL were successfully injected and that monocytes were labeled. Interestingly, the spleen R1 decreased between day 1 and day 4, potentially reflecting migration of labeled monocytes from the spleen to the infarcted heart. R1 measurements in the spleen of the labeled mice showed no change in R1 between days 4 and 7 after MI. This suggested that the splenic monocytes labeled with DLL did not release any gadolinium between days 4 and 7.

Previously, monocyte and/or macrophage tracking with MR imaging has been examined by using iron oxide particles (9–12) and perfluorocarbon emulsions (7). Using DLL and R1 mapping, we achieved positive contrast and quantification and measured a time course that agrees with that in prior histologic studies. While iron oxide particles may have important limitations for this application (eg, negative contrast and an insensitivity to monocyte and/or macrophage depletion), fluorine 19 MR imaging using perfluorocarbon emulsions to label monocytes and/or macrophages shows promise as another quantitative technique (7). However, to date this method has not been evaluated for quantifying monocyte and/or macrophage kinetics.

We used Gd-DTPA-bis(stearylamide)–based liposomes; however, Gd-DOTA-DSPE–based liposomes may be a better choice because of improved stability of gadolinium in the complex (29). While one explanation for the observed changes in myocardial R1 over location and time is the infiltration and depletion of labeled monocytes and/or macrophages, other factors, such as leakage of gadolinium from the cells or changes in the effective relaxivity (30), could also affect the results. Previously, a few studies have shown that the uptake of specific types of liposomes containing various factors can alter the biologic activity of monocytes and/or macrophages (4,31). In this study, we did not investigate the effect of DLL on macrophages and their biologic activity, and it is possible that some effect occurred. In the present study, we have shown, by using R1 mapping and histologic examination, that the region of R1 lengthening corresponds closely with the location of bright green CD68-positive cells. We have also shown, using histologic examination, that CD68-positive cells are colocalized with DiI-positive cells. However, it is possible that the fluorescent probe and the paramagnetic label separated over time. The contrast agent in its current formulation is not intended to be used in human subjects, as soluble Gd-DTPA-bis-amide has been implicated in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, and it is unlikely that Gd-DTPA-bis(stearylamide)–based liposomes would be safe. The more recent Gd-DOTA-lipid used for liposome labeling (29) may be safer, but this remains to be investigated. Although our study demonstrated the spatiotemporal course of monocytes and/or macrophages after MI, these methods do not distinguish between the two subsets of monocytes, namely the inflammatory Ly-6Chi and the reparative Ly-6Clo monocytes (6,32). Further studies to design and evaluate contrast agents specific for the different types of monocytes are warranted. Other limitations of our study included restricted section coverage and long imaging times. Furthermore, post-MI edema causes lengthening of T1 (22), which made it essential to measure the T1 in unlabeled postinfarct control mice. This necessitated a greater number of imaging experiments. Because edema affects T2 as well as T1, the extra control experiments should also apply to an approach where T2-shortening contrast agents are applied. Fluorine 19 MR imaging would not have this disadvantage, because this approach is free of varying background signal.

In conclusion, R1 mapping after labeling monocytes with T1-shortening DLL enables the in vivo measurement of monocyte and/or macrophage spatiotemporal kinetics after MI. These methods, applied in mice or other animals, may be used in future studies to investigate the roles of specific genes or experimental therapies in post-MI monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration and related changes in infarct healing, angiogenesis, myocardial perfusion, myocardial function, and LV remodeling.

Advances in Knowledge.

• Look-Locker MR imaging performed after labeling monocytes with liposomes containing gadolinium enables quantitative in vivo mapping of monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration of the heart in a mouse model of myocardial infarction.

• Serial measurements of ΔR1 (where ΔR1 is the difference in R1 between liposome-labeled and unlabeled infarcts) depicted the time course of monocyte and/or macrophage infiltration of the infarct zone, showing a small increase in ΔR1 on day 1 after MI, a maximum increase on day 4 after MI, and a decrease on day 7 after MI.

Implication for Patient Care.

• These methods may be used in future preclinical studies to investigate the role of monocytes and/or macrophages in infarct healing, repair, and regeneration and to assess the efficacy of novel macrophage-targeted therapies in cardiovascular regenerative medicine.

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: N.K.N. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. Y.X. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. A.L.K. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: institution receives money from patents related to ultrasound plus bubble targeted tumor therapy from Philips; institution has minor stock ownership of privately held company, Targeson, on microbubble ultrasound contrast targeting that A.L.K. cofounded. Other relationships: none to disclose. M.H.V. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. C.H.M. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. J.L. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. C.M.K. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. B.A.F. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: institution has grants or grants pending from AstraZeneca, which contributed $75,000 to support research not directly related to this publication. Other relationships: none to disclose. F.H.E. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: institution has grants or grants pending from Siemens Medical Solutions. Other relationships: none to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jack Roy, BS, for his help in regard to MR imaging. The authors also thank Professor Jae K. Lee, PhD, and Wenjun Xin, MS, for their help with statistics.

Received August 31, 2011; revision requested October 26; revision received January 25, 2012; accepted February 24; final version accepted March 19. N.K.N.

Supported by American Heart Association Predoctoral Grant 11PRE7440117. J.L. and F.H.E. supported by US-Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant 2007290. B.A.F. supported by American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 09GRNT2261123.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 EB001763).

See also Science to Practice in this issue.

Abbreviations:

- DENSE

- displacement encoding with stimulated echoes

- DLL

- dual-labeled liposome

- DTPA

- diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- LV

- left ventricle

- MI

- myocardial infarction

References

- 1.Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2002;53(1):31–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circ Res 2012;110(1):159–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert JM, Lopez EF, Lindsey ML. Macrophage roles following myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2008;130(2):147–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harel-Adar T, Ben Mordechai T, Amsalem Y, Feinberg MS, Leor J, Cohen S. Modulation of cardiac macrophages by phosphatidylserine-presenting liposomes improves infarct repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(5):1827–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leor J, Rozen L, Zuloff-Shani A, et al. Ex vivo activated human macrophages improve healing, remodeling, and function of the infarcted heart. Circulation 2006;114(1 Suppl):I94–I100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK. Monocytes: protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2010;121(22):2437–2445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flögel U, Ding Z, Hardung H, et al. In vivo monitoring of inflammation after cardiac and cerebral ischemia by fluorine magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2008;118(2):140–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattrey RF, Andre MP. Ultrasonic enhancement of myocardial infarction with perfluorocarbon compounds in dogs. Am J Cardiol 1984;54(1):206–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montet-Abou K, Daire JL, Hyacinthe JN, et al. In vivo labelling of resting monocytes in the reticuloendothelial system with fluorescent iron oxide nanoparticles prior to injury reveals that they are mobilized to infarcted myocardium. Eur Heart J 2010;31(11):1410–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sosnovik DE, Nahrendorf M, Deliolanis N, et al. Fluorescence tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of myocardial macrophage infiltration in infarcted myocardium in vivo. Circulation 2007;115(11):1384–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Yang Y, Yanasak N, Schumacher A, Hu TC. Temporal and noninvasive monitoring of inflammatory-cell infiltration to myocardial infarction sites using micrometer-sized iron oxide particles. Magn Reson Med 2010;63(1):33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Liu J, Yang Y, Cho SH, Hu TC. Assessment of cell infiltration in myocardial infarction: a dose-dependent study using micrometer-sized iron oxide particles. Magn Reson Med 2011;66(5):1353–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996.

- 14.Yang Z, Berr SS, Gilson WD, Toufektsian MC, French BA. Simultaneous evaluation of infarct size and cardiac function in intact mice by contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging reveals contractile dysfunction in noninfarcted regions early after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004;109(9):1161–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabalka G, Buonocore E, Hubner K, Moss T, Norley N, Huang L. Gadolinium-labeled liposomes: targeted MR contrast agents for the liver and spleen. Radiology 1987;163(1):255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szoka F, Jr, Papahadjopoulos D. Procedure for preparation of liposomes with large internal aqueous space and high capture by reverse-phase evaporation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1978;75(9):4194–4198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Klibanov AL, Beyers RJ, et al. Abstract 3364: Serial MRI assessment of macrophage activity in the murine heart after myocardial infarction using gadolinium-labeled liposomes as a positive contrast agent [abstr]. Circulation 2007;116:II_759 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein MC, Weissmann G. Enzyme replacement via liposomes. Variations in lipid compositions determine liposomal integrity in biological fluids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1979;587(2):202–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Beckerleg AM, Torchilin VP, Huang L. Activity of amphipathic poly(ethylene glycol) 5000 to prolong the circulation time of liposomes depends on the liposome size and is unfavorable for immunoliposome binding to target. Biochim Biophys Acta 1991;1062(2):142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandervelde S, van Amerongen MJ, Tio RA, Petersen AH, van Luyn MJ, Harmsen MC. Increased inflammatory response and neovascularization in reperfused vs. non-reperfused murine myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Pathol 2006;15(2):83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang F, Liu YH, Yang XP, Xu J, Kapke A, Carretero OA. Myocardial infarction and cardiac remodelling in mice. Exp Physiol 2002;87(5):547–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beyers RJ, Smith RS, Xu Y, et al. T2-weighted MRI of post-infarct myocardial edema in mice. Magn Reson Med 2012;67(1):201–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandsburger MH, Janiczek RL, Xu Y, et al. Improved arterial spin labeling after myocardial infarction in mice using cardiac and respiratory gated look-locker imaging with fuzzy C-means clustering. Magn Reson Med 2010;63(3):648–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim D, Gilson WD, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Myocardial tissue tracking with two-dimensional cine displacement-encoded MR imaging: development and initial evaluation. Radiology 2004;230(3):862–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spottiswoode BS, Zhong X, Hess AT, et al. Tracking myocardial motion from cine DENSE images using spatiotemporal phase unwrapping and temporal fitting. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2007;26(1):15–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein FH, Yang Z, Gilson WD, Berr SS, Kramer CM, French BA. MR tagging early after myocardial infarction in mice demonstrates contractile dysfunction in adjacent and remote regions. Magn Reson Med 2002;48(2):399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilson WD, Yang Z, French BA, Epstein FH. Measurement of myocardial mechanics in mice before and after infarction using multislice displacement-encoded MRI with 3D motion encoding. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;288(3):H1491–H1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science 2009;325(5940):612–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hak S, Sanders HM, Agrawal P, et al. A high relaxivity Gd(III)DOTA-DSPE-based liposomal contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2009;72(2):397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kok MB, Strijkers GJ, Nicolay K. Dynamic changes in 1H-MR relaxometric properties of cell-internalized paramagnetic liposomes, as studied over a five-day period. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2011;6(2):69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Amerongen MJ, Harmsen MC, van Rooijen N, Petersen AH, van Luyn MJ. Macrophage depletion impairs wound healing and increases left ventricular remodeling after myocardial injury in mice. Am J Pathol 2007;170(3):818–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med 2007;204(12):3037–3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.