Abstract

Novel protein-coding genes can arise either through re-organization of pre-existing genes or de novo1,2. Processes involving re-organization of pre-existing genes, notably following gene duplication, have been extensively described1,2. In contrast, de novo gene birth remains poorly understood, mainly because translation of sequences devoid of genes, or “non-genic” sequences, is expected to produce insignificant polypeptides rather than proteins with specific biological functions1,3-6. Here, we formalize an evolutionary model according to which functional genes evolve de novo through transitory proto-genes4 generated by widespread translational activity in non-genic sequences. Testing this model at genome-scale in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we detect translation of hundreds of short species-specific open reading frames (ORFs) located in non-genic sequences. These translation events appear to provide adaptive potential7, as suggested by their differential regulation upon stress and by signatures of retention by natural selection. In line with our model, we establish that S. cerevisiae ORFs can be placed within an evolutionary continuum ranging from non-genic sequences to genes. We identify ~1,900 candidate proto-genes among S. cerevisiae ORFs and find that de novo gene birth from such a reservoir may be more prevalent than sporadic gene duplication. Our work illustrates that evolution exploits seemingly dispensable sequences to generate adaptive functional innovation.

Both genome-wide surveys and analyses of individual cases have shown that de novo gene birth has occurred throughout the evolution of many lineages, potentially impacting species-specific adaptations and evolutionary radiations1,2,5,6,8,9. Genes are thought to emerge de novo when non-genic sequences become transcribed, acquire ORFs and the corresponding non-genic transcripts access the translation machinery1,2,4,5,8. However, it is hard to reconcile this proposed mechanism with expectations that non-genic sequences should lack translational activity and, even if translated, should encode insignificant polypeptides1,3,4,6. Evidence of associations between non-genic >transcripts and ribosomes has suggested that non-genic sequences may occasionally be translated, which could provide raw material for natural selection6. It has also been speculated that genes that originate de novo could initially be simple and gradually become more complex over evolutionary time4. These ideas are consistent with reports showing that genes that emerged recently are shorter, less expressed and more rapidly diverging than other genes1,10-13. We developed an integrative evolutionary model whereby de novo gene birth proceeds through intermediate and reversible proto-gene stages, mirroring the well-described pseudo-gene stages of gene death (Fig. 1a)14.

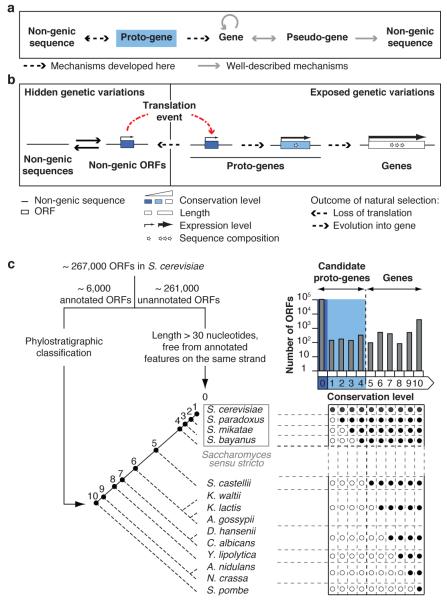

Fig. 1. From non-genic sequences to genes through proto-genes.

a, Proto-genes mirror for gene birth the well-described pseudo-genes for gene death. Circular arrow: gene origination from pre-existing genes, such as through gene duplication. Pseudo-genes are highly related to existing genes but have accumulated disabling mutations and translation of functional proteins is no longer possible14. The premise that pseudo-gene formation represents irreversible gene death has been challenged by reports of pseudo-gene resurrection14 (bidirectional arrow). After enough evolutionary time pseudo-gene decay renders them indistinguishable from non-genic sequences (unidirectional arrow). Whereas pseudo-genes resemble known genes, proto-genes resemble no known genes. Proto-genes arise in non-genic sequences and either revert to non-genic sequences or evolve into genes (bidirectional arrow). There can be no reversion of genes to proto-genes (unidirectional arrow) since gene decay engenders pseudo-genes. b, Details of the proposed model for the gradual emergence of protein-coding genes in non-genic sequences via proto-genes. Full arrows indicate the reversible emergence of ORFs in non-genic transcripts, or of transcripts containing non-genic ORFs. Examples where transcript appearance precedes ORF appearance have been described1,2,8, but the reverse order of events cannot be ruled out. Broken arrows representing expression level symbolize transcription (hidden genetic variation) or transcription and translation (exposed genetic variation). The variations in width of these arrows reflect changes in expression level resulting, at least in part, from changes in regulatory sequences. Sequence composition refers to codon usage, amino acid abundances and structural features. c, Assigning conservation levels to S. cerevisiae ORFs. Conservation levels of annotated ORFs were assigned according to comparisons along the reconstructed phylogenetic tree, by inferring their presence (full circles) or absence (empty circles) in the different species according to the phylostratigraphy principle (Supplementary Information)1. Top right: number of ORFs assigned to each conservation level (logarithmic scale).

We investigated this model at genome-scale in the context of de novo gene birth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae8,10. In S. cerevisiae, a minimal length threshold of 300 nucleotides was originally used to delineate ORFs likely to be genes from non-genic ORFs occurring by chance in non-genic sequences15. The resulting gene catalogue has undergone numerous adjustments16, with currently ~6,000 ORFs annotated as genes and ~261,000 unannotated ORFs containing at least three codons considered non-genic ORFs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Nongenic sequences are broadly transcribed in S. cerevisiae17, their overexpression is mostly non-toxic18, and the corresponding transcripts can associate with ribosomes, often at AUGs6,19. We reasoned that translation of non-genic ORFs could be more common than expected. Such translation events would not systematically lead to de novo gene birth, since the corresponding polypeptides would not necessarily have specific biological functions. Instead, upon translation, non-genic ORFs would become proto-genes (Fig. 1b). Proto-genes would provide adaptive potential6 by exposing genetic variations that are usually hidden in non-genic sequences. A subset of proto-genes could occasionally be retained over evolutionary time, for instance if providing an advantage to the organism under specific environmental conditions. Retained proto-genes could gradually evolve the characteristics of genes, while other proto-genes might lose the ability to be translated. Such a reservoir of proto-genes would allow evolutionary innovations to be attempted without affecting existing genes.

This evolutionary model leads to the following predictions: i) the structural and functional characteristics of S. cerevisiae ORFs (e.g. length, expression level or sequence composition) should reflect an evolutionary continuum ranging from non-genic ORFs to genes; ii) many non-genic ORFs should be translated; iii) ORFs that emerged recently should occasionally have adaptive functions retained by natural selection.

To examine these predictions, we estimated the order of emergence of S. cerevisiae ORFs (Fig. 1c). Annotated ORFs were classified into 10 groups based on their conservation throughout the Ascomycota phylogeny (Supplementary Fig. 2). Of ~6,000 annotated ORFs, ~2% are found only in S. cerevisiae (ORFs1) (Supplementary Fig. 2)10 and ~12% are found only in the four closely related Saccharomyces sensu stricto species (ORFs1-4). The ~88% of annotated ORFs found outside of this group (ORFs5-10) are well characterized and can confidently be considered genes. ORFs1-4 are poorly characterized and their annotation as genes is debatable (Supplementary Fig. 2)16,20. The weak conservation of ORFs1-4 suggests that they emerged recently, which we corroborated using gene duplication events to control for relative time of emergence (Supplementary Fig. 3). We estimate that over 97% of ORFs1-4 originated de novo rather than by cross-species transfer, which could also explain their weak conservation (Supplementary Information). ORFs1-4 often partially overlap ORFs5-10, which seems incompatible with cross-species transfer, or preferentially lie within subtelomeric regions whose instability may facilitate de novo emergence (Supplementary Fig. 4). In addition to classifying ORFs1-10, we assigned a conservation level of 0 to ~108,000 unannotated ORFs longer than 30 nucleotides and free from overlap with annotated features on the same strand (ORFs0) (Supplementary Information). ORFs0 and ORFs1-4 constituted our initial list of candidate proto-genes.

To test the evolutionary continuum prediction, we first verified that ORF conservation level correlates positively with length and expression level (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 5)1,10-12. These correlations suggest that genes evolve from non-genic ORFs that lengthen and increase in expression level over evolutionary time. A negative correlation between ORF length and expression level21 was observed among ORFs5-10, but not among ORFs1-4 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, some ORFs may increase in expression level at different rates than they increase in length over evolutionary time. Lengthening of ORFs could occur by loss of stop codons, possibly following translational read-through, by shift of start codons or by duplication followed by fusion with other ORFs10,22. Increase in ORF expression level could be mediated by recruitment of existing regulatory elements1. The proportion of ORFs located in the vicinity of transcription factor binding sites increases with conservation level, suggesting that novel regulatory elements could also emerge (Fig. 2a)1.

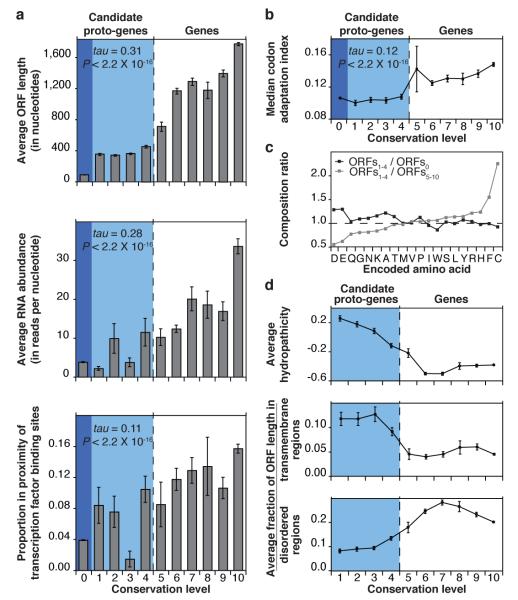

Fig. 2. Existence of an evolutionary continuum ranging from non-genic ORFs to genes through proto-genes.

a, Length (top; error bars represent s.e.m.), RNA expression level (middle; error bars represent s.e.m.), and proximity to transcription factor binding sites (bottom; error bars represent standard error of the proportion) of ORFs correlate with conservation level. P and tau: Kendall’s correlation statistics. Estimation of RNA abundance from RNAseq25 in rich conditions. The positive correlation between proximity to transcription factor binding sites and conservation level is shown for a window of 200 nucleotides and holds when considering windows of 300, 400 and 500 nucleotides (Kendall’s tau = 0.14, 0.16, 0.17, respectively; P < 2.2 × 10−16 in each case). b, Codon bias increases with conservation level. Codon bias estimated using the codon adaptation index (Supplementary Information). P and tau: Kendall’s correlation statistics. Error bars represent s.e.m. The large s.e.m. observed for ORFs5 may be related to the whole genome duplication event (Supplementary Fig. 3). c,Relative amino acid abundances shift with increasing conservation level. For each encoded amino acid, the ratio between its frequency in ORFs1-4 and its frequency in ORFs5-10 (gray), or the ratio between its frequency in ORFs1-4 and its frequency in ORFs0 (black), is plotted. Enrichment of cysteine in proteins encoded by ORFs1-4 relative to those encoded by ORFs5-10 (P < 1.8 × 10−150, hypergeometric test) corresponds to 3.6 ± 0.1 residues (mean, s.e.m.) per translation product. d, Predicted structural features of ORF translation products correlate with conservation level. ORFs0 were not included in these analyses as their short length hinders the reliability of structural predictions. Error bars represent s.e.m.

In line with a study of codon evolution in metazoans23, we observed a positive correlation between codon usage bias and conservation level (Fig. 2b). Relative abundances of amino acids in proteins encoded by ORFs1-4 show levels intermediate between those in proteins encoded by ORFs5-10 and in hypothetical translation products of ORFs0 (Fig. 2c), similar to observations in bacteria24. Likely due to this biased sequence composition, ORFs1-4 exhibit a higher hydropathicity, a higher tendency to form transmembrane regions and a lower propensity for intrinsic structural disorder10 than ORFs5-10 (Fig. 2d). Taken together, our observations support the existence of an evolutionary continuum ranging from non-genic ORFs to genes.

To assess the extent of non-genic translation, we searched for signatures of translation of ORFs0 at genome-scale in a ribosome footprinting dataset generated in both rich and starvation conditions25. In this dataset, ~1% of sequencing reads could not be mapped to ORFs1-10. We developed a stringent pipeline to detect unequivocal translation signatures for ORFs0 located on transcripts associated with ribosomes (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 6). We found that 1,139 of ~108,000 ORFs0 show such evidence of translation (ORFs 0+). This number is significantly higher than expected if the ribosome footprinting assay was non-specific, or if the presence of ribosomes on non-genic transcripts was unrelated to the presence of ORFs0 (Fig. 3b). These ORFs 0+ are enriched in adenine at position -3 from the start codon, which likely favours translation initiation (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Information). We verified that ORFs 0+ did not originate from gene duplication or cross-species transfer and are not genes that have failed to be annotated due to their short length (Supplementary Information). The 1,139 ORFs 0+ therefore appear to be translated non-genic ORFs.

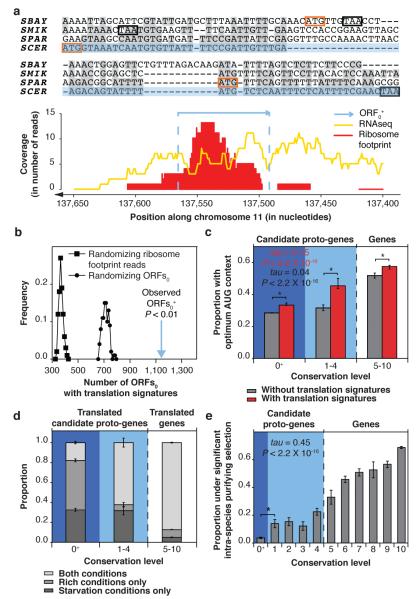

Fig. 3. Translation and adaptive potential of recently emerged ORFs.

a, Example of an ORFs 0+ showing signatures of translation in starvation conditions. Syntenic regions in Saccharomyces sensu stricto species are aligned. Orange and black boxes: in-frame start and stop sites, respectively; SCER: S. cerevisiae; SPAR: S. paradoxus; SMIK: S. mikatae; SBAY: S. bayanus. b, Significance of the observed number of ORFs 0+. Distribution of the number of ORFs0 expected to show signatures of translation if the ribosome footprinting assay were non specific (as modelled by randomizing footprint reads positions 100 times; squares), or if the presence of ribosomes on non-genic transcripts were not related to the presence of ORFs0 (as modelled by randomizing ORFs0 positions 100 times; circles). P: empirical P value. c, AUG context of ORFs with and without translation signatures. The presence of an adenine at position -3 from the start codon indicates optimum AUG context (Supplementary Information). P and tau: Kendall’s correlation statistics. Asterisks (*) mark significant differences between ORFs with and without translation signatures (P < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test). d, Candidate proto-genes tend to undergo condition-specific translation. e, Signatures of intra-species purifying selection. The positive correlation holds when only considering ORFs that are free from overlap with ORFs1-10 (Supplementary Fig. 7), and is not entirely driven by the interdependence between strength of purifying selection and expression level (Supplementary Information)29,30. Asterisk (*) marks a significant difference in proportion of ORFs under significant intra-species purifying selection between ORFs 0+ and ORFs1 (P = 0.0001, hypergeometric test). P and tau: Kendall’s correlation statistics. Error bars represent standard error of the proportion in all panels.

We detected strong differential translation of ORFs 0+ and ORFs1-4 in starvation or rich conditions, whereas most ORFs5-10 are translated in both conditions (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 6). We found that the binding sites of four transcription factors involved in mating and stress response are preferentially located close to ORFs 0+ and ORFs1-4 (Supplementary Table 1) and that ORFs1-4 are enriched in the Gene Ontology term “response to stress” (Supplementary Table 2). Recently emerged ORFs may provide adaptive functions in response to environmental stress.

Retention by natural selection was measured by comparing the genome sequences of eight S. cerevisiae strains to evaluate the tendency of ORF sequences to be purged of non-synonymous mutations (purifying selection) relative to expectations under neutral evolution. Most ORFs 0+ and ORFs1-4 do not exhibit a significant deviation from neutral evolution, yet ~3% of ORFs 0+ and 9-25% of ORFs1-4 appear under purifying selection (Fig. 3e). This fraction increases with conservation level, in line with the proposed evolutionary continuum (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Information). Our observations suggest that recently emerged ORFs occasionally acquire adaptive functions that are retained by natural selection, in agreement with findings in primates and with evolutionary models derived from inter-species comparisons12,13,26.

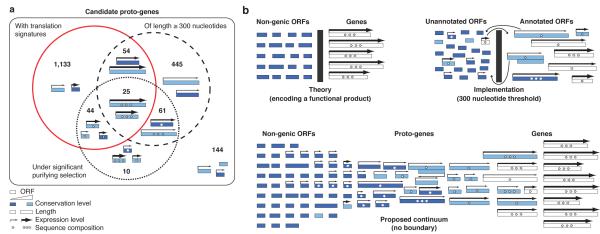

Overall, our results show that de novo gene birth could proceed through proto-genes. From the initial comprehensive set of candidate proto-genes (all ORFs0 and ORFs1-4), we excluded ORFs0 that appear to lack translation signatures according to our stringent pipeline (Supplementary Fig. 6). The 25 ORFs4 that are longer than 300 nucleotides, show signatures of translation and are under purifying selection, can confidently be considered genes despite being weakly conserved. The remaining 1,891 ORFs (1,139 ORFs 0+ and 752 ORFs1-4) present characteristics intermediate between non-genic ORFs and genes, meeting our proto-gene designation (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 3). We propose to place these ORFs in a continuum where strict annotation boundaries no longer have to be set (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. Identification of proto-genes in a continuum ranging from non-genic ORFs to genes.

a, Characterization of candidate proto-genes (ORFs 0+ and ORFs1-4). Venn diagram not drawn to scale. b, The binary model of annotation (top) and the proposed continuum (bottom).

Gene birth mechanisms involving re-organization of pre-existing genes, notably following gene duplication, have long been regarded as the predominant source of evolutionary innovation1,2. Since the split between S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus, sporadic gene duplications have generated between 1 and 5 novel genes27. In contrast, 19 of the 143 ORFs1 that arose de novo during the same evolutionary period were found under purifying selection. Therefore, de novo gene birth appears more prevalent than previously supposed3,10,12, in agreement with recent estimations in humans and other primates1,9. The involvement of proto-genes in de novo emergence of protein-coding genes in S. cerevisiae likely holds for other species and may extend to RNA genes and regulatory elements. Examination of translation program remodelling upon stress, in light of our evolutionary model, may further understanding of phenotypic diversity and plasticity of cellular systems7,28.

Methods Summary

Detection of translation signatures

The mapping of ribosome footprint reads to ORFs does not necessarily indicate full-length, ORF-specific translation events6,25. To model the number of ORFs 0+ expected if the detected presence of ribosomes on non-genic sequences was not related to the presence of ORFs0, we randomized the positions of ORFs0 while maintaining their length distribution and the observed positions of RNAseq and footprint reads. To model the number of ORFs 0+ expected if footprint reads observed outside of annotated ORFs were non-specific, we randomized the positions of footprint reads throughout non-genic sequences while maintaining the length distribution of footprint reads, the positions of RNAseq reads and the positions of ORFs0. We optimized three parameters with regard to these two null models: i) the proportion of ORF length covered in RNAseq and footprint reads was fixed at 50% minimum; ii) the factor by which the number of footprint reads per nucleotide in the ORF should be higher than the number of footprint reads per nucleotide in surrounding up- and downstream windows was fixed at a minimum of 5; iii) the size of these windows was fixed at 300 nucleotides. Any two ORFs0 that partially overlap on the same strand and show translation signatures in the same experimental conditions were both eliminated from the set of ORFs0 considered to show translation signatures.

Significant purifying selection signatures

We estimated the number of synonymous mutations per synonymous site (dS) and the number of non-synonymous mutations per non-synonymous site (dN) for each ORF present without disruptive mutations in eight S. cerevisiae strains. The likelihood of the dN/dS ratio for each ORF present without disruptive mutations in eight S. cerevisiae strains was determined under two distinct null models: assuming neutral evolution (the rates of synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions are equal) and not assuming neutral evolution. All ORFs with dN/dS < 1 and P < 0.05 (chi-square distribution of likelihoods with one degree of freedom) were considered to be subject to significant purifying selection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Duret, E. Levy, J. Vandenhaute, Q. Li, H. Yu, P. Braun, M. Dreze, C. Foo, M. Mann, N. Kulak, J. Cox, C. Maire and S. Jhavery-Schneider as well as members of the Center for Cancer Systems Biology (CCSB) in particular A. Dricot-Ziter, A. MacWilliams, F. Roth, Y. Jacob and D. Hill for discussions and proofreading. We apologize for the omission of relevant studies that we could not cite due to space limitations. A.R. was supported by a National Institute of Health Pioneer Award, a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). I.W. is a HHMI fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Institute. G.A.B. was supported by American Cancer Society Postdoctoral fellowship 117945-PF-09-136-01-RMC. M.V. is a Chercheur Qualifié Honoraire from the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS, Wallonia-Brussels Federation, Belgium). This work was supported by the grant R01-HG006061 from the National Human Genome Research Institute awarded to M.V.

Footnotes

Full methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions A.-R.C., I.W., M.E.C. and M.V. conceived the project. A.-R.C. led the project and performed most of the analyses. T.R. evaluated cross-species transfer events, optimized the ribosome footprint analysis pipeline and assisted in other analyses. I.W. designed the conservation level tool and calculated most of the purifying selection statistics. M.A.Y. aligned the sequencing reads. B.S. predicted disordered and transmembrane regions and assisted in the cross-species transfer analyses. N.S. and B.C. assisted in analyses. G.A.B. and J.S.W. shared their expertise in ribosome footprinting data analysis and provided the meiosis ribosome footprinting raw and processed data. A.-R.C., T.R., M.E.C. and M.V. designed the figures. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Tautz D, Domazet-Loso T. The evolutionary origin of orphan genes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:692–702. doi: 10.1038/nrg3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaessmann H. Origins, evolution, and phenotypic impact of new genes. Genome Res. 2010;20:1313–1326. doi: 10.1101/gr.101386.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob F. Evolution and tinkering. Science. 1977;196:1161–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.860134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siepel A. Darwinian alchemy: Human genes from noncoding DNA. Genome Res. 2009;19:1693–1695. doi: 10.1101/gr.098376.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khalturin K, Hemmrich G, Fraune S, Augustin R, Bosch TC. More than just orphans: are taxonomically-restricted genes important in evolution? Trends Genet. 2009;25:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson BA, Masel J. Putatively noncoding transcripts show extensive association with ribosomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2011;3:1245–1252. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarosz DF, Taipale M, Lindquist S. Protein homeostasis and the phenotypic manifestation of genetic diversity: principles and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2010;44:189–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai J, Zhao R, Jiang H, Wang W. De novo origination of a new protein-coding gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;179:487–496. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu DD, Irwin DM, Zhang YP. De novo origin of human protein-coding genes. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekman D, Elofsson A. Identifying and quantifying orphan protein sequences in fungi. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;396:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipman DJ, Souvorov A, Koonin EV, Panchenko AR, Tatusova TA. The relationship of protein conservation and sequence length. BMC Evol. Biol. 2002;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf YI, Novichkov PS, Karev GP, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. The universal distribution of evolutionary rates of genes and distinct characteristics of eukaryotic genes of different apparent ages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7273–7280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901808106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai JJ, Petrov DA. Relaxed purifying selection and possibly high rate of adaptation in primate lineage-specific genes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2010;2:393–409. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng D, Gerstein MB. The ambiguous boundary between genes and pseudogenes: the dead rise up, or do they? Trends Genet. 2007;23:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver SG, et al. The complete DNA sequence of yeast chromosome III. Nature. 1992;357:38–46. doi: 10.1038/357038a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisk DG, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C genome annotation: a working hypothesis. Yeast. 2006;23:857–865. doi: 10.1002/yea.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagalakshmi U, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the yeast genome defined by RNA sequencing. Science. 2008;320:1344–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.1158441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyer J, et al. Large-scale exploration of growth inhibition caused by overexpression of genomic fragments in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R72. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-r72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brar GA, et al. High-resolution view of the yeast meiotic program revealed by ribosome profiling. Science. 2012;335:552–557. doi: 10.1126/science.1215110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li QR, et al. Revisiting the Saccharomyces cerevisiae predicted ORFeome. Genome Res. 2008;18:1294–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.076661.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen R, Gerstein M. Analysis of the yeast transcriptome with structural and functional categories: characterizing highly expressed proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1481–1488. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giacomelli MG, Hancock AS, Masel J. The conversion of 3′ UTRs into coding regions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:457–464. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prat Y, Fromer M, Linial N, Linial M. Codon usage is associated with the evolutionary age of genes in metazoan genomes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009;9:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yomtovian I, Teerakulkittipong N, Lee B, Moult J, Unger R. Composition bias and the origin of ORFan genes. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:996–999. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, Weissman JS. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vishnoi A, Kryazhimskiy S, Bazykin GA, Hannenhalli S, Plotkin JB. Young proteins experience more variable selection pressures than old proteins. Genome Res. 2010;20:1574–1581. doi: 10.1101/gr.109595.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao LZ, Innan H. Very low gene duplication rate in the yeast genome. Science. 2004;306:1367–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1102033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayden EJ, Ferrada E, Wagner A. Cryptic genetic variation promotes rapid evolutionary adaptation in an RNA enzyme. Nature. 2011;474:92–95. doi: 10.1038/nature10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pal C, Papp B, Hurst LD. Highly expressed genes in yeast evolve slowly. Genetics. 2001;158:927–931. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.2.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drummond DA, Raval A, Wilke CO. A single determinant dominates the rate of yeast protein evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:327–337. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.