Summary

Translational control depends on phosphorylation of eIF2α by PKR-like ER kinase (PERK). To examine the role of PERK in cognitive function, we selectively disrupted PERK expression in the adult mouse forebrain. In the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of PERK-deficient mice, eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression were diminished and associated with enhanced behavioral perseveration, decreased prepulse inhibition, reduced fear extinction, and impaired behavioral flexibility. Treatment with the glycine transporter inhibitor SSR504734 normalized eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF4 expression, and behavioral flexibility in PERK-deficient mice. Moreover, PERK and ATF4 expression were reduced in the frontal cortex of human schizophrenic patients. Together, our findings reveal that PERK plays a critical role in information processing and cognitive function, and that modulation of eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression may represent an effective strategy for treating behavioral inflexibility associated with several neurological disorders including schizophrenia.

Keywords: PERK, translational control, eIF2α, ATF4, prefrontal cortex, cognitive control, glycine transporter-1 inhibitor, behavioral flexibility, schizophrenia

Introduction

In mammals, long-lasting memory formation requires new mRNA and protein synthesis (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009; Kandel, 2001; Kelleher et al., 2004; Richter and Klann, 2009). The translation of mRNAs is highly regulated at the level of initiation by numerous translational control molecules, including the translation initiation factor eIF2 (Sonenberg and Dever, 2003). During this rate-limiting step, eIF2 interacts with initiator tRNA and GTP to facilitate loading of the ternary complex onto the 40S ribosomal subunit, which is essential for new rounds of protein synthesis (Harding et al., 1999). Although phosphorylation of the α subunit of eIF2 results in general inhibition of translation, it paradoxically stimulates the translation of several upstream open reading frame (uORF)-containing mRNAs, including the transcriptional modulator activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) (Vattem and Wek, 2004). Notably, ATF4 and its homologues play critical roles as repressors of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-mediated synaptic plasticity and memory in diverse phyla (Abel et al., 1998; Bartsch et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2003). Thus, eIF2α phosphorylation controls two distinct processes that are essential for the consolidation of new memories: de novo general protein synthesis and gene-specific translation of ATF4 mRNA. Furthermore, reduction of eIF2α phosphorylation in mice lacking the eIF2α kinase GCN2 and in heterozygous knockin mice with a mutation on serine 51 of eIF2α results in a lowered threshold for inducing long-lasting late phase long-term potentiation (L-LTP) and consolidation of long-term memory (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2005; Costa-Mattioli et al., 2007). Moreover, mice harboring a deletion of the double-stranded (ds) RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) show a similar decrease in threshold for inducing L-LTP and consolidation of long-term memory (Zhu et al., 2011). Conversely, increased eIF2α phosphorylation in transgenic mice overexpressing PKR causes increased expression of ATF4, impaired L-LTP, and memory deficits (Jiang et al., 2010). Collectively, these findings suggest that the proper regulation of eIF2α phosphorylation is required for normal synaptic plasticity and memory.

The PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) was initially characterized as a ubiquitously-expressed ER-localized protein kinase that phosphorylates eIF2α to rapidly reduce protein synthesis during ER stress (Harding et al., 2000). Global inactivation of PERK in mice results in multiple developmental defects, including early onset diabetes, growth retardation, skeletal abnormalities, and pancreatic atrophy (Harding et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002). Consistent with this, mutations in the human PERK gene (EIF2AK3) causes Wolcott-Rallison syndrome (WRS), a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by permanent neonatal diabetes, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, liver dysfunction, and pancreas insufficiency (Delepine et al., 2000; Julier and Nicolino, 2010; Rubio-Cabezas et al., 2009). In some cases of WRS, patients develop clinical features associated with mental retardation (Delepine et al., 2000; Reis et al., 2011; Senee et al., 2004; Thornton et al., 1997). Moreover, cell lines lacking either TSC1 or TSC2, the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) proteins, and both mouse and human tumors from TSC model mice and TSC patients, respectively, exhibit activation of the PERK-eIF2α axis (Ozcan et al., 2008). Together, these analyses suggest a crucial role for PERK in normal cellular homeostasis, growth, viability, and development. However, the precise role of PERK in memory formation and cognition has not been explored.

Given that PERK functions as a critical modulator of a number of cellular processes requiring precise translational control, we explored the role of PERK in regulating protein synthesis-dependent cognitive function in the mammalian brain. Here, we show that a targeted disruption of PERK in the mouse forebrain results in significant reduction of phosphorylated eIF2α and ATF4 expression in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Behavioral studies with PERK-deficient mice revealed multiple phenotypes consistent with impaired cognition and information processing. Moreover, treatment with the glycine transporter inhibitor SSR504734 normalized eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression, and restored behavioral flexibility in the PERK mutant mice. Furthermore, the molecular deficits observed in the mutant mice were recapitulated in the frontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia, but not in patients with bipolar disorder. These findings expand the repertoire of PERK as a regulator of translational control to include cognitive processes in the adult brain and highlight the modulation of eIF2α phosphorylation as a key site for influencing translational control underlying the pathophysiology of cognitive deficits commonly associated with neurological disorders.

Results

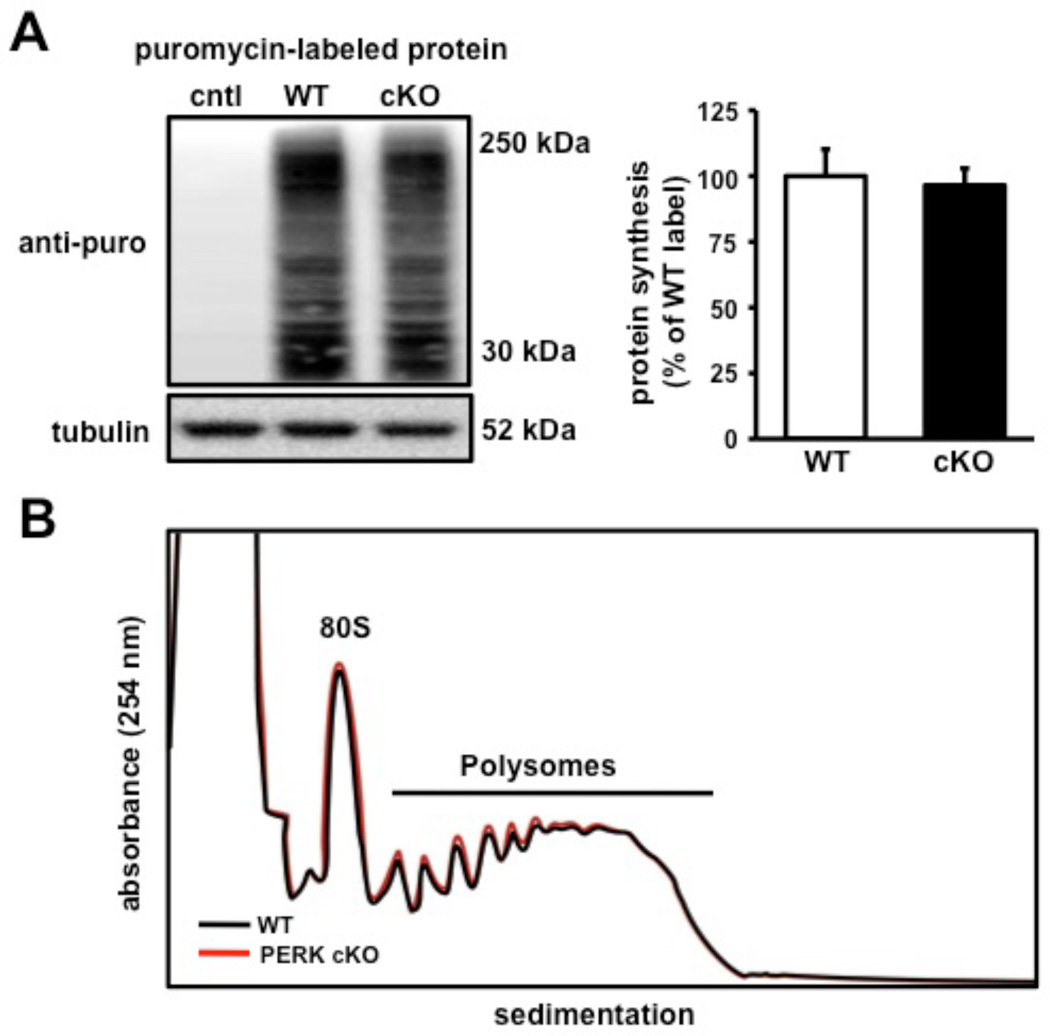

PERK regulates eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression in the brain

To evaluate the precise role of PERK in translation-dependent forms of memory in the mammalian brain, we generated mice containing a forebrain-specific CamkIIα-Cre transgene (Tsien et al., 1996) and conditional alleles of Perk (Zhang et al., 2002) (PerkloxP; Figure 1A). The onset of Cre activity occurs at approximately two to three weeks after birth (Tsien et al., 1996), permitting normal brain development in the presence of Perk. The CamkIIα-Cre; PerkloxP/loxP conditional knockout mice (PERK cKO hereafter) contain an ablation of PERK that is predominantly limited to the forebrain. The presence of the conditional PerkloxP allele and Cre transgene was determined using PCR-specific primers (Figure 1A). Western blot assays confirmed efficient Cre-mediated deletion of PerkloxP in several areas of the forebrain isolated from PERK cKO mice, including the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex (Figures 1B, 1D, and S1A). Despite the reduction of PERK in these regions, Nissl-stained sections indicated that mutant mice did not show gross alterations in brain morphology compared to their wild-type littermates (Figure 1C). Notably, the prefrontal cortex region harbored the greatest ablation of PERK, which was correlated with a significant reduction of phosphorylated eIF2α (Figures 1D and S1B). To confirm that the genetic disruption was specifically restricted to the forebrain, we examined PERK levels in the cerebellum, muscle, and peripheral organs and observed that PERK expression was indistinguishable between mutant and wild-type mice (Figures 1D, 1E, and S1A). Moreover, examination of layer II/III of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) by immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed nearly a complete absence of phosphorylated eIF2α staining in PERK cKO mice (Figure 1F). Although robust phosphorylation of eIF2α can inhibit global protein synthesis, gene-specific translation of ATF4 is most sensitive to eIF2α phosphorylation (Vattem and Wek, 2004). We observed that a decrease in eIF2α phosphorylation was associated with reduced ATF4 expression (Figures 1G and S1C) in the prefrontal cortex of PERK cKO mice. However, we found that the decrease in eIF2α phosphorylation had a minimal effect on global translation using a puromycin-based assay adapted from the SUnSET technique that labels protein synthesis (Schmidt et al., 2009) (Figure 2A) and polysome profiling analysis from sucrose gradients (Figure 2B). Thus, these findings indicate that a forebrain-specific disruption of PERK results in reduced eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression in the prefrontal cortex.

Figure 1. Forebrain-specific deletion of Perk suppresses eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression in the prefrontal cortex.

(A) Schematic for the conditional allele for Perk. Top, black triangles represent two loxP sites flanking exons 7–9 (E7–E9) of the Perk gene and grey boxes represent primers (568F and 568R1) designed to detect recombination. Middle, upon recombination with CaMKIIα-Cre, Perk is deleted in a forebrain-specific manner. Bottom, PCR identification of alleles of PerkloxP and CaMKIIα-driven Cre. (B) Representative Western blot analysis confirming disruption of PERK in hippocampal area CA1. (C) Top, Nissl-stained coronal sections of prefrontal cortex. Bottom, whole brain from wild-type (WT) and PERK cKO mice. (D) Representative Western blot showing CaMKIIα-driven Cre disruption of PERK in other regions of the brain from WT and PERK cKO mice. (E) Representative Western blot showing PERK levels in cKO mice are expressed at similar levels to those in WT mice in tissues outside the central nervous system. (F) Immunohistochemical detection of phosphorylated eIF2α in layer II/III of the medial prefrontal cortex showing decreased expression in PERK cKO (right panel) compared to WT (left panel). Scale bar, 200 µm. (G) Representative Western blot showing decreased ATF4 expression in the prefrontal cortex of PERK cKO mice compared to their WT littermates. Quantification of PERK, eIF2α phosphorylation, and ATF4 expression from the Western blot analyses is shown in Figure S1.

Figure 2. Disruption of PERK-regulated translation in the prefrontal cortex does not alter protein synthesis.

(A) Left, Western blot image showing newly synthesized proteins labeled with puromycin using the SUnSET technique (see Experimental Procedures). Coronal prefrontal slices from wild-type and PERK cKO mice were treated with puromycin (5µg/mL) for 45 mins. Right, Protein synthesis levels remain unaltered between both genotypes. (cntl, no puromycin control, n=4; WT, n=4; cKO, n=4). (B) Absorbance profile (254 nm) of WT (black trace) and PERK cKO (red trace) prefrontal cortical fractions sedimented through a 20–50% linear sucrose gradient in the presence of cycloheximide.

PERK cKO mice show impaired information processing and behavioral flexibility

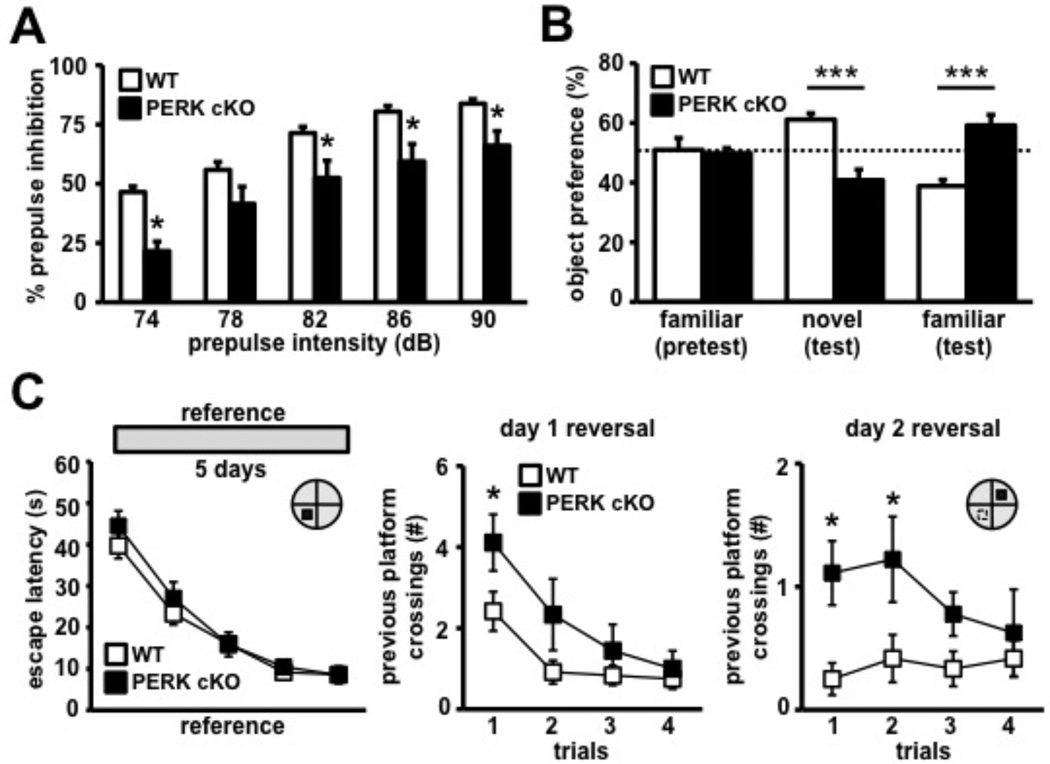

To examine whether the disruption of PERK resulted in altered cognitive function, we tested male PERK cKO mice in a series of behavioral paradigms. We examined the PERK cKO mice for prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the startle response, a reliable and robust measure of sensorimotor gating and information processing abilities (Swerdlow et al., 2008). PPI involves a short, low-intensity acoustic stimulus (prepulse) that inhibits the reaction of an organism to a startling stimulus (Swerdlow et al., 2008). The PERK cKO mice showed a deficit in PPI of the auditory startle response compared to their wild-type littermates (Figure 3A). No difference between genotypes was observed with the presentation of the startling stimulus alone, suggesting a normal baseline startle response in PERK cKO mice (data not shown). PERK cKO mice display significantly enhanced vertical locomotor activity in the open field arena (Figure S2A). However, we observed no difference between genotypes for the distance traveled, time spent in the center zone of the open field, and in the closed arms versus the aversive open arms of the elevated plus maze (Figures S2B, S2C and S2D), suggesting normal anxiety levels in PERK cKO mice. These findings indicate that disruption of PERK-directed translational control results in deficits in information processing and enhanced vertical activity.

Figure 3. PERK cKO mice display reduced prepulse inhibition and enhanced behavioral perseveration in novel object recognition and MWM tasks.

(A) PERK cKO mice exhibit impaired prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex across varying prepulse intensities: 74, 78, 82, 86, and 90 dB. WT, n=11; cKO, n=9 (*p<0.05, two-way repeated measure ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). (B) PERK cKO mice display enhanced perseveration for the familiar object in the novel object recognition task. WT, n=8; cKO, n=14 (***p<0.001, two-way repeated measures ANOVA). (C) Left, escape latency across 5 days of MWM reference platform task shows that PERK cKO mice acquired the spatial hidden platform task similarly to wild-type controls. Right, PERK cKO mice exhibit higher number of previous day platform position crossing during day 2 reversal phase of task compared to controls. WT, n=12; cKO, n=9 (*p<0.05, two-way repeated measures ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test). See also Figure S3 and Movies S1 and S2.

To further examine the role of PERK in working memory and cognitive function, we subjected adult PERK cKO mice to behavioral tasks that require precise cognitive control. First, we found that PERK cKO mice exhibit enhanced preference for the familiar object in the novel object recognition task (Figure 3B). Next, we determined that PERK cKO mice and their wild-type counterparts were able to use spatial cues to learn the position of a hidden platform (Figure 3C) in the Morris water maze (MWM), a hippocampus-dependent water escape task (Morris, 1984). During probe trials, both genotypes showed similar preferences for the target quadrant of the pool that previously contained the platform (Figure S3A), suggesting that PERK cKO mice have normal spatial reference memory. To specifically examine whether PERK is involved in spatial reversal learning in the MWM, we switched the location of the hidden platform to the opposite quadrant and challenged the ability of the mice to learn the new platform position. Notably, on the second day of reversal training, the wild-type mice exhibited normal spatial reversal learning (Figure 3C and Movie S1), but the PERK cKO mice displayed perseveration for the originally learned platform position (Figure 3C and Movie S2). However, these perseverative behaviors were not associated with repetitive or obsessive-compulsive-like behavior as the PERK cKO mice displayed normal marble burying and grooming behavior (Figures S2E and S2F). PERK cKO mice also spent more time in the previous training quadrant, but exhibited normal escape latency during the visible platform task (Figures S3B and S3C). Taken together, these results indicate that a forebrain-specific disruption of PERK causes enhanced perseverative behaviors and impaired spatial reversal learning.

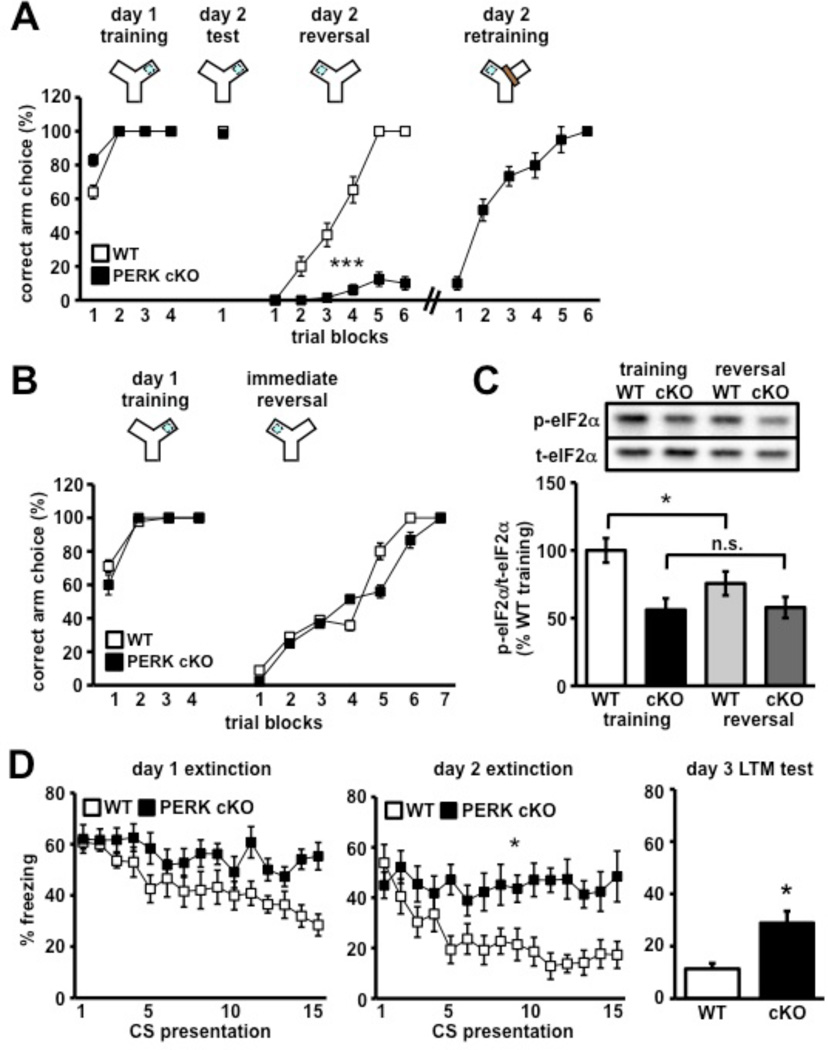

As a further test of our hypothesis that PERK regulates memory and cognitive flexibility, PERK cKO mice were trained in a Y-water maze reversal task. Briefly, mice were trained to locate an escape platform in one arm of a water-based Y-maze. After 24 hours, the escape platform was switched to the opposing arm and the behavioral flexibility of the mice to learn the new escape location was measured. The number of trials to criterion (9/10 correct) was achieved at trial 30 by all wild-type mice (Figure 4A and Movie S3). In contrast, 12 out of 13 mutant mice persistently swam towards the previously trained arm choice, exhibiting severe behavioral inflexibility (Figure 4A). A retraining paradigm was employed to allow these mice to make three consecutive correct choices (Figure 4A). During retraining, a physical wall was used to block the incorrect arm; however, PERK cKO mice continued to swim towards the incorrect path and into the wall (Movie S4). The PERK cKO mice required an additional 28 trials to meet this criterion (Figure S3D). Upon retraining, PERK cKO mice showed comparable rates of reversal learning as their wild-type counterparts (Figure 4A). Interestingly, PERK cKO mice exhibited normal behavioral flexibility if the escape platform was switched to the adjacent arm immediately after training on the first day (Figure 4B). This finding suggests that the behavioral inflexibility exhibited by PERK cKO mice requires memory consolidation, a protein synthesis-dependent process (McGaugh, 2000). PERK cKO mice exhibited normal motor ability on the rotarod task, suggesting that the disruption of PERK does not affect cerebellar-dependent motor functions (Figure S4). Together, these findings reveal that a post-developmental disturbance of PERK is sufficient to trigger impaired behavioral flexibility.

Figure 4. PERK cKO mice exhibit cognitive control deficits and behavioral inflexibility.

(A) Percent correct arm choice per trial block number (5 trials/trial block) during training, test, reversal and retraining phases of Y-maze reversal task. (//) denotes when 12 out of 13 PERK cKO mice had to be retrained because they continued to swim to the originally trained arm choice. WT, n=10; cKO, n=13 (***p<0.001, two-way ANOVA). See also Figure S3 and Movies S3 and S4. (B) PERK cKO mice no longer perseverate to originally trained arm choice following same-day immediate reversal training. WT, n=8; cKO, n=9. (C) Western blot analysis of eIF2α phosphorylation in PFC of wild-type and PERK cKO mice 30 mins following training and reversal learning. WT, n=6; cKO, n=6. (*p<0.05, one-way ANOVA; n.s., not significant). (D) Left and Middle, percent of time spent freezing across 2 days of fear extinction training protocol (15 CS presentations/day) indicates that PERK cKO mice exhibit impaired fear extinction learning compared to controls (*p<0.05, two-way ANOVA). Right, percent freezing time during long-term memory extinction test on day 3. WT, n=8; cKO, n=10 (*p<0.05, Student’s t-test). All data represent mean values ± SEM.

The behavioral results described above suggest that eIF2α phosphorylation is normally altered during reversal learning. To test this hypothesis and to determine whether the removal of PERK has any effect on learning-dependent changes in eIF2α phosphorylation, PERK cKO mice and their wild-type littermates were subjected to the Y-water maze reversal task and frontal cortices from both genotypes were harvested and assayed for phosphorylated eIF2α 30 minutes following training for reversal learning. We found that wild-type mice exhibited decreased eIF2α phosphorylation after reversal learning (Figure 4C). In contrast, although basal phosphorylation of eIF2α was reduced, there was no further reduction in eIF2α phosphorylation in the PERK cKO mice (Figure 4C). Furthermore, we found that mice lacking the eIF2α kinase GCN2 exhibited normal reversal learning (Figure S5), suggesting that behavioral flexibility is regulated specifically by a pool of eIF2α that is normally phosphorylated by PERK. Taken together, these findings suggest that reversal learning normally decreases eIF2α phosphorylation and that PERK phosphorylates a specific pool of eIF2α to regulate behavioral flexibility.

Flexible behavior also is afforded by proper extinction, an active, protein synthesis-dependent learning process driven by the mPFC (Santini et al., 2004), which triggers the formation of a newly updated memory that inhibits the initial memory (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2004). In light of our findings suggesting that PERK regulates behavioral flexibility, we next determined whether fear extinction was compromised by the absence of PERK. Interestingly, we found that PERK cKO mice have impaired fear extinction memory compared to their wild-type littermates (Figure 4D). Collectively, these findings suggest that PERK-directed translation regulates extinction learning. Moreover, disruption of PERK leads to profound behavioral symptoms associated with deficits in information processing and cognitive function.

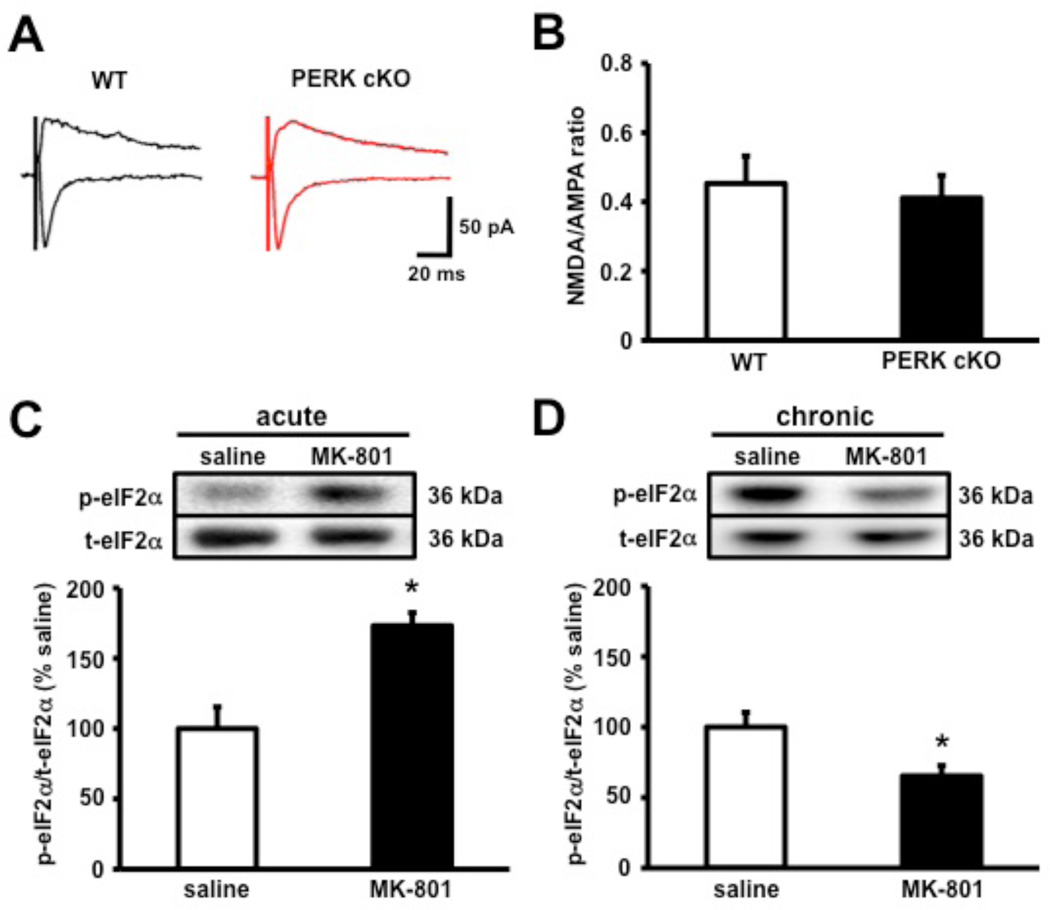

NMDA-R hypofunction modulates eIF2α phosphorylation in the prefrontal cortex

Compelling evidence suggesting a role for N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R) hypofunction underlying the pathophysiology of cognitive impairments stem from findings that NMDA-R blockers such as PCP, ketamine, and MK-801 induce impaired working memory, behavioral flexibility, reversal learning, and extinction in mice and humans (Abdul-Monim et al., 2006; Dix et al., 2010; Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Krystal et al., 1994). Because the PERK-deficient mice display multiple cognitive impairments associated with NMDA-R hypofunction, we proceeded to record NMDA-R-mediated excitatory currents in layer II of the mPFC of PERK cKO mice and their wild-type littermates. However, we found that the NMDA-to-AMPA ratio was indistinguishable between PERK cKO mice and their wild-type littermates (Figures 5A and 5B), suggesting that NMDA-R function is normal in the PERK cKO mice. We then proceeded to determine whether NMDA-R hypofunction could cause abnormal PERK-directed translation by determining whether administration of MK-801 in wild-type mice could mimic the decreased eIF2α phosphorylation observed in the PERK cKO mice. Wild-type mice received a single dose (acute) or 15 daily injections (chronic) of either saline or MK-801 (0.2 mg/kg for acute; 0.1 mg/kg for chronic) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections. Frontal cortices from saline- and MK-801-treated wild-type mice were harvested and assayed for phosphorylated eIF2α. We found that acute MK-801 treatment enhanced eIF2α phosphorylation (Figure 5C), whereas chronic MK-801 treatment decreased eIF2α phosphorylation (Figure 5D), suggesting that the time course of NMDA-R hypofunction bi-directionally regulates eIF2α phosphorylation. Consistent with this idea, longer-term increases in eIF2α phosphorylation elicits protein phosphatase 1/GADD34-directed feedback dephosphorylation of this translation factor (Marciniak et al., 2004). These data suggest that NMDA-R hypofunction alters eIF2α phosphorylation in the prefrontal cortex.

Figure 5. NMDA-R hypofunction alters eIF2α phosphorylation in the prefrontal cortex.

(A) Sample traces of EPSCs recorded from PFC slices of WT (black) and PERK cKO (red) mice. (B) Average NMDA/AMPA EPSCs ratios from pyramidal cells in layer II of the mPFC show no significant difference between either genotype. WT, n=16; cKO, n=17. (C) eIF2α phosphorylation is increased in the frontal cortex of wild-type mice upon single-dose (acute) treatment with MK-801 (0.2 mg/kg, i.p.) compared to saline. saline, n=3; MK-801, n=3 (D) Western blot analysis showing a decrease of eIF2α phosphorylation following 15 days (chronic) MK-801 (0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) treatment. saline, n=4; MK-801, n=5 (*p<0.05, Student’s t-test). All data represent mean values ± SEM.

SSR504734 restores cognitive function and PERK-regulated translation

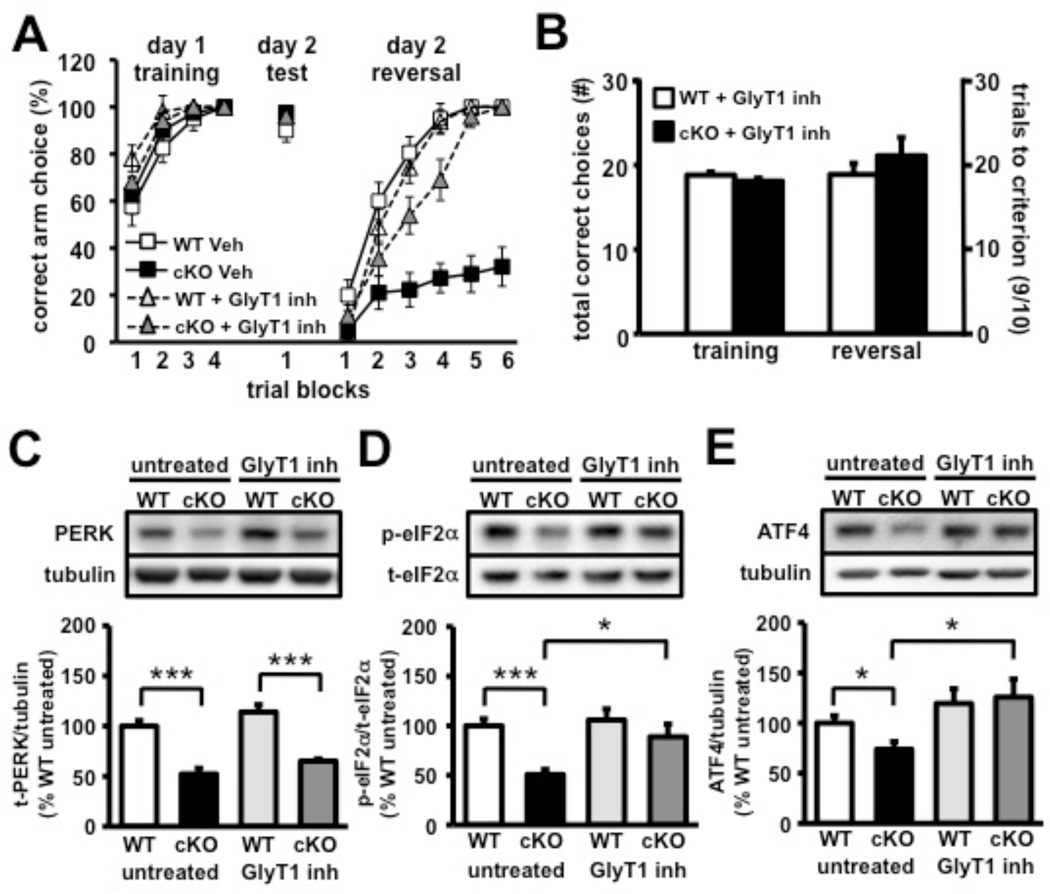

One therapeutic strategy for the treatment of impaired behavioral flexibility involves the enhancement of NMDA-R function by increasing synaptic glycine, an NMDA-R co-activator, by blocking glycine reuptake via inhibition of glycine transporter-1 (GlyT1) (Javitt, 2008). Several previous studies have shown that the GlyT1 inhibitor, SSR504734 (Depoortere et al., 2005), improves behavioral flexibility, reversal learning, and overall cognitive function (Black et al., 2009; Singer et al., 2009). To evaluate whether SSR504734 could rescue the cognitive impairments exhibited by the PERK cKO mice, the Y-water maze reversal task was revisited to test wild-type and PERK cKO mice following chronic administration of SSR504734 (20 mg/kg; 21 days) by i.p. injection. Remarkably, following chronic treatment with SSR504734, the PERK cKO mice displayed normal reversal learning when compared to their wild-type littermates (Figures 6A and 6B and Movies S5 and S6). However, we found that chronic treatment with SSR504734 did not reverse either the enhanced vertical activity (Figure S6A) or the sensorimotor gating impairment (Figure S6B) displayed by the PERK cKO mice. These data demonstrate that chronic SSR504734 administration can uniquely enhance cognitive ability and restore behavioral flexibility in the PERK cKO mice.

Figure 6. Treatment with the GlyT1 inhibitor SSR504734 rescues prefrontal cortex-dependent molecular and cognitive deficits in PERK cKO mice.

(A) Y-maze reversal task performance following 21 days of treatment with either saline (veh) or glycine transporter-1 inhibitor (GlyT1 inh.) SSR504734 (20 mg/kg, i.p.). (B) Upon chronic GlyT1 inhibitor treatment, PERK cKO mice behave like wild-type (WT) controls and require similar number of trials to meet criterion during reversal phase of the Y-maze task. See also Movies S5 and S6. (C) Western blot analysis of basal PERK expression in prefrontal cortex of WT and cKO (untreated) compared to chronic treatment with GlyT1 inhibitor. (D) eIF2α phosphorylation is normalized in prefrontal cortex of PERK cKO mice following GlyT1 inhibitor treatment. (E) ATF4 protein expression is enhanced in prefrontal cortex of PERK cKO mice following GlyT1 inhibitor treatment compared to untreated controls. (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001, two-way ANOVA). All data represent mean values ± SEM.

To determine whether chronic SSR504734 treatment also could rescue aberrant PERK-directed translation, frontal cortices from SSR504734-treated wild-type and PERK mutant mice were analyzed for total PERK, phosphorylated eIF2α and ATF4 expression levels by Western blotting. We found that PERK cKO mice treated with SSR504734 had significantly enhanced levels of phosphorylated eIF2α and increased ATF4 expression compared to untreated PERK mutants (Figures 6D and 6E). There was no significant difference in total PERK levels between the treated and untreated PERK cKO mice (Figure 6C). Collectively, these results indicate that chronic treatment with the GlyT1 inhibitor SSR504734 can rescue disrupted PERK-regulated translation in the prefrontal cortex, presumably by either activating another eIF2α kinase such as GCN2 and/or PKR, or by inhibiting the protein phosphatase 1/GADD34 complex that dephosphorylates eIF2α (Ma and Hendershot, 2003).

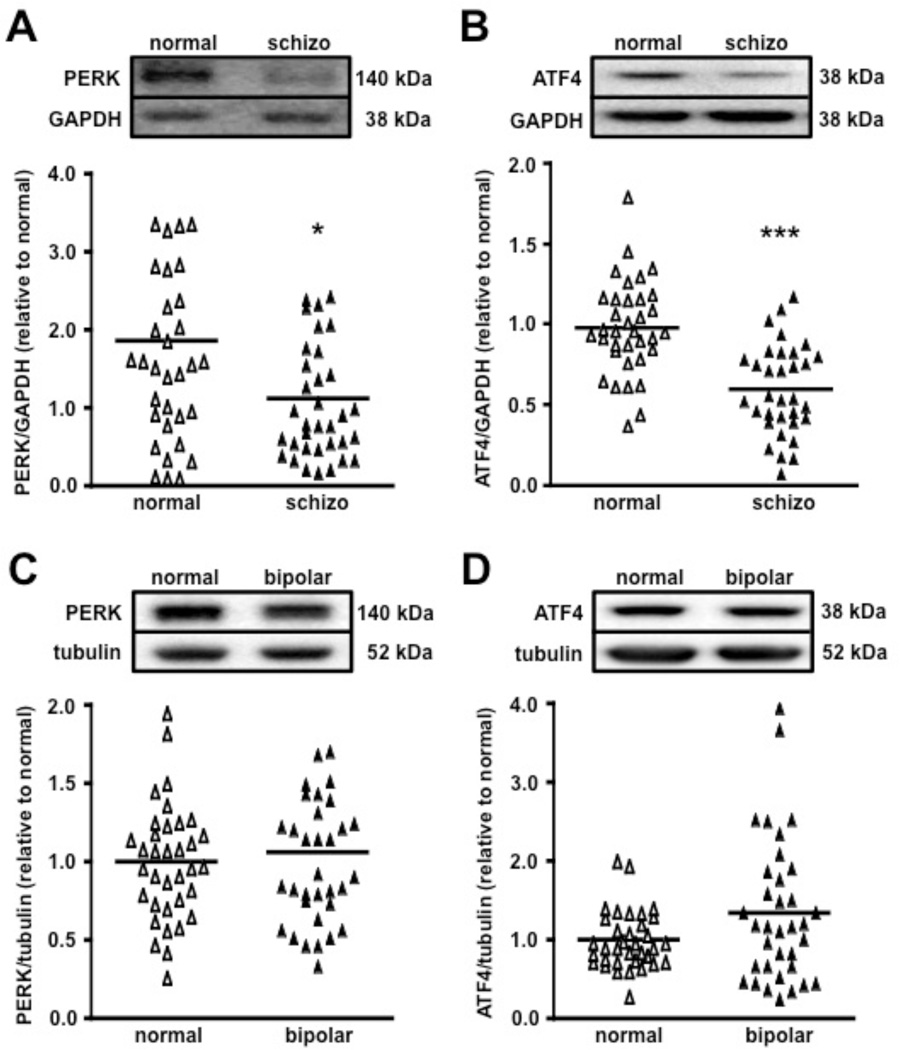

Aberrant PERK-regulated translation in frontal cortex of schizophrenic patients

Upon discovering that mice with a targeted disruption of PERK exhibit multiple behavioral features consistent with cognitive impairments associated with several mental illnesses including schizophrenia, we hypothesized that aberrant PERK-directed translation might be involved in the pathophysiology of human schizophrenia. To test this idea, we obtained postmortem human schizophrenic frontal cortex samples and employed Western blot analysis to examine the expression of PERK, phosphorylation of eIF2α, and expression of ATF4. All samples from the Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI) Array collection were matched for age, sex, and race. A summary of the relevant patient demographic information is provided (Table S1). Spearman correlation analysis showed no significant effect of age, brain pH, postmortem interval (PMI) or lifetime antipsychotic usage on the levels of PERK or ATF4 expression (Table S2). Brain pH and PMI was negatively correlated with eIF2α phosphorylation and total eIF2α levels. ANCOVA with pH and PMI as covariates failed to confirm the diagnostic differences initially observed with ANOVA for the eIF2α phosphorylation analysis (data not shown). Thus, we were unable to assess the regulation of eIF2α phosphorylation in postmortem schizophrenic samples. Frontal cortex samples from normal control patients displayed a considerable level of PERK, which was significantly reduced in the schizophrenia samples (Figure 7A). Moreover, ATF4 expression was markedly reduced in the schizophrenia brains compared to controls (Figure 7B). To investigate how broadly PERK-directed translation is involved in mental illnesses, we next examined PERK and ATF4 expression in the frontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder compared to normal controls. In contrast to schizophrenic brains, PERK and ATF4 levels were unaltered in the frontal cortex of bipolar patients compared to normal control patients (Figures 7C and 7D). Taken together, these findings suggest that disturbances of PERK-regulated translation of ATF4 in the frontal cortex may specifically contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Figure 7. PERK and ATF4 expression is reduced in the frontal cortex of schizophrenic, but not bipolar patients.

(A) PERK expression levels normalized by GAPDH levels. normal, n=35; schizophrenia (schizo), n=35 (*p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). Scatter plots display the variability and differences in the protein expression leves normalized by each GAPDH expression levels. (B) Gene-specific translation of ATF4 is reduced in the frontal cortex of schizophrenic patients. normal, n=35; schizo, n=33 (***p<0.001, one-way ANOVA). (C) PERK expression levels do not differ between control and bipolar patient brain samples. PERK expression normalized by tubulin levels. normal, n=35; bipolar, n=35 (p>0.05, n.s., one-way ANOVA). (D) ATF4 expression remains unaltered in the frontal cortex of bipolar patients compared to normal controls. normal, n=35; bipolar, n=35 (p>0.05, n.s., one-way ANOVA). A crossbar on each scatter plot represents mean expression levels for each group.

Discussion

PERK is a key regulator of translation control pathways known to be involved in learning and memory formation. Previous studies have shown that global inactivation of PERK causes severe developmental defects, precluding a comprehensive analysis of its role in cellular and molecular processes underlying memory and cognitive function. In our studies, we used the Cre-lox expression system to achieve a temporally and spatially restricted inactivation of Perk in the postnatal forebrain. Our findings reveal a previously unrecognized role of PERK-dependent translational regulation in cognitive function and provide molecular insights into the pathophysiology of cognitive impairment. We found that disruption of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway in the mouse prefrontal cortex recapitulates multiple behavioral phenotypes consistent with impaired cognition and information processing. Furthermore, our studies identify the modulation of eIF2α phosphorylation as a potential molecular target for therapeutic agents designed to prevent cognitive symptoms associated with a wide variety of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Earlier studies provide strong evidence to suggest that gene-specific translation of ATF4 is critical for the modulation of hippocampus-dependent long-term synaptic potentiation and memory formation. In particular, transgenic mice expressing a dominant negative inhibitor of C/EBP proteins were reported to have reduced ATF4 expression, which was associated with a facilitation of hippocampus-dependent longterm synaptic plasticity and memory formation (Chen et al., 2003). Moreover, a reduction of ATF4 expression in mice lacking the eIF2α kinase GCN2 and heterozygous knockin mice with a mutation on serine 51 of eIF2α results in a lowered threshold for eliciting long-lasting LTP and memory (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2005; Costa-Mattioli et al., 2007). Taken together, these studies suggest that regulation of ATF4 expression, mediated by GCN2-dependent phosphorylation of eIF2α, is required for activity-dependent, enduring changes in neuronal function. Expanding on these findings, we show that in the prefrontal cortex of PERK-deficient mice, reduced eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression is associated with severe behavioral inflexibility. Thus, our data suggests that the regulation of ATF4 mRNA translation, mediated by PERK-directed phosphorylation of eIF2α, is critical for normal cognitive function. Because of its conserved role as a memory repressor in diverse phyla (Bartsch et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2003; Costa-Mattioli et al., 2005; Yin et al., 1994), we speculate that ATF4 normally acts to destabilize the initial memory trace and consequently, when ATF4 expression is reduced in the prefrontal cortex, the initial memory trace prevails despite changes in sensory and contextual information.

Our data suggests that reduction of PERK expression and ATF4 translation in the frontal cortex may specifically contribute to the pathophysiology of human schizophrenia (Figure 7). Interestingly, ATF4 has previously been shown to interact with Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) (Chubb et al., 2008; Muir et al., 2008; Sawamura et al., 2008), a genetic risk factor for mental illnesses, including mood disorders and schizophrenia. In addition, mutations in selective regions of the DISC1 gene result in a loss of interaction with ATF4 (Morris et al., 2003). Moreover, the ATF4 gene is positioned at chromosome 22q13, a hotspot for several schizophrenia-related susceptibility genes (Lewis et al., 2003; Mowry et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2003). Finally, polymorphisms in the ATF4 locus have been associated with schizophrenia in male patients (Qu et al., 2008). Thus, multiple studies support the notion that ATF4, whose translation is tightly regulated by eIF2α phosphorylation, is correlated with schizophrenia. It should be noted that in addition to the central regulator ATF4, other genes recently have been identified that are preferentially translated by eIF2α phosphorylation, which suggests that additional factors participate downstream of PERK to regulate cognitive function (Dey et al., 2010; Jackson et al., 2010).

Behavioral studies with the PERK mutant mice revealed multiple phenotypes consistent with cognitive and information processing deficits, which have been implicated as core features of numerous mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Bora et al., 2009; Goos et al., 2009; Lesh et al., 2011; Solomon et al., 2009). In particular, PERK-deficient mice exhibited reduced prepulse inhibition (Figure 3A), a sensorimotor gating mechanism that restricts processing of sensory information (Bitsios et al., 2006; Braff et al., 2001). In addition, PERK cKO mice showed enhanced preference for the familiar object compared with the novel object in a hippocampus- and entorhinal cortex-dependent novel object recognition task (Figure 3B). One explanation for these results is that PERK is important for frontal and temporal cortex-dependent sensory information processing. Thus, in the absence of PERK, mice are unable to inhibit responses to sensory or cognitive information and have enhanced perseveration. Consistent with this notion, our results from the MWM and Y-maze tests indicate that PERK cKO mice have reduced inhibitory control of a previously-reinforced response, which causes enhanced perseveration, impaired reversal learning, and behavioral inflexibility (Figures 3C and 4A and Movies S2 and S4). Furthermore, the results from our fear extinction studies highlight an equally important role for PERK in PFC-directed updating of behavior (Figure 4C). Collectively, these results suggest that PERK regulates sensory information processing, thereby inducing deficits in various cognitive paradigms when eliminated.

Previous studies have shown that a reduction of eIF2α phosphorylation in mice lacking the eIF2α kinase GCN2 and in heterozygous knockin mice with a mutation on serine 51 of eIF2α results in a lowered threshold for the consolidation of long-term memory (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2005; Costa-Mattioli et al., 2007). Similar to the PERK cKO mice, GCN2 and eIF2α-S51A mutant mice showed reduced eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression, although these reductions were global and constitutive rather than forebrain-specific and post-developmental. However, the behavioral phenotypes of the GCN2 and eIF2α-S51A mutant mice were quite different from the PERK cKO mice. Unlike the PERK cKO mice, we found that GCN2 KO mice showed normal reversal learning in the Y-water maze reversal task (Figure S5). These complementary studies indicate that even in the face of similar biochemical profiles, such as reduced eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression, additional mechanisms and levels of regulation exist to further modulate pools of eIF2α that are eventually reflected by distinct behavioral phenotypes. It also is important to emphasize that the PERK cKO mice are post-developmental knockout mice where the disruption of PERK occurs approximately two to three weeks after birth. In contrast, GCN2 KO and eIF2α-S51A mutant mice, as well as PKR (another eIF2α kinase) KO mice, are all global, constitutive knockout mice. Thus, the behavioral phenotypes displayed by the GCN2, eIF2α-S51A, and PKR mutant mouse lines could be due to developmental complications, whereas the PERK cKO mice are not.

One current model for the pathophysiology of PCP-induced psychosis and schizophrenia involves the hypofunction of NMDA-R in GABAergic fast-spiking interneurons (Belforte et al., 2010; Lisman et al., 2008; Nakazawa et al., 2011). Loss of NMDA-R function in interneurons is thought to result in disinhibition of pyramidal neurons in the cortex and hippocampus, asynchronous pyramidal neuron activation, hyperexcitability of cortical networks, and cognitive impairment. Intriguingly, our findings suggest that while selective ablation of PERK in pyramidal neurons does not alter NMDA-R function (Figures 5A and 5B), chronic NMDA-R hypofunction elicits a decrease of eIF2α phosphorylation in the prefrontal cortex (Figures 5C and 5D). Based on these results, we speculate that NMDA-R hypofunction in interneurons causes cortical excitation, dysregulation of PERK, and decreased eIF2α phosphorylation in pyramidal neurons, resulting in impaired cognition. Consistent with this notion, a recent study showed that deletion of the eIF2α kinase PKR in mice results in reduced GABAergic transmission, increased network excitability, and altered cognition (Zhu et al., 2011). However, whether selective ablation of PERK in pyramidal neurons associates with altered cortical network excitability remains to be determined. Furthermore, it is possible that reduced NMDA-R function causes a disruption of PERK-directed translation specifically in GABAergic interneurons to dampen inhibitory control of pyramidal neurons and impair cognitive function. Future studies examining the role of PERK in various neuronal subtypes, in particular GABAergic interneurons, will provide molecular insight into the role of eIF2α in the pathophysiology of cognitive impairment associated with multiple neurological disorders.

Interestingly, it has been shown that enhancement of NMDA-R function by treatment with the GlyT1 inhibitor SSR504734 improves behavioral flexibility, reversal learning, and overall cognitive function (Black et al., 2009; Depoortere et al., 2005; Singer et al., 2009). Consistent with these studies, our findings indicate that SSR504734 uniquely enhanced behavioral flexibility (Figures 6A and 6B and Movies S5 and S6) without altering enhanced vertical activity and sensorimotor gating impairments displayed by the PERK cKO mice. Furthermore, chronic SSR504734 treatment was found to restore aberrant eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression, but not disrupted PERK levels in the PFC of PERK cKO mice (Figures 6C, 6D and 6E). Thus, our results indicate that chronic inhibition of GlyT1 can normalize disrupted PERK-regulated translation, presumably by either activating other eIF2α kinases such as GCN2 and/or PKR, or by inhibiting the protein phosphatase 1/GADD34 complex that dephosphorylates eIF2α (Ma and Hendershot, 2003). Future studies are required to address whether chronic SSR504734 treatment enhances GCN2 activity, enhances PKR activity, or inhibits protein phosphatase 1/GADD34 complex in the prefrontal cortex of PERK mutant mice.

Under normal physiological conditions, it has been reported that systemic administration of SSR504734 improves behavioral flexibility and cognitive function in wild-type mice (Singer et al., 2009). In contrast, we found that although chronic SSR504734 treatment had no effect on the performance of the wild-type mice (Figure 6A), it restored the behavioral flexibility of the PERK cKO mice (Figure 6A). Moreover, we found that SSR504734 could not only rescue the behavioral deficits, but also could restore the molecular anomalies exhibited by the PERK cKO mice (Figures 6D and 6E). Thus, our findings provide direct evidence that SSR504734 can modulate eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression that is tightly correlated with reversal of the behavioral inflexibility displayed by the PERK cKO mice. Future studies are required to determine whether chronic SSR504734 treatment can restore the dysregulated eIF2α-ATF4 axis in wild-type mice treated chronically with agents such as MK-801 and PCP that induce NMDA-R hypofunction and are used to model schizophrenia.

A rapidly expanding list of neurological disorders and neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex, and ASD have been linked to dysregulated protein synthesis (Auluck et al., 2010; Hoeffer and Klann, 2010; Kelleher and Bear, 2008; Ozcan et al., 2008; Palop and Mucke, 2010; Santini and Klann, 2011). Consistent with these findings, our results suggest that post-developmental disruption of PERK-regulated translational control is sufficient to trigger cognitive control impairments consistent with several disorders, including schizophrenia. In conclusion, these findings emphasize the critical importance of PERK in normal cognitive processes. Further studies elucidating the specific role of PERK-regulated translation in the brain may provide new avenues to tackle such widespread and often debilitating neurological disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Transgenic Mice

Floxed Perk (PerkloxP/loxP) mice were generated as described previously (Zhang et al., 2002). Mice expressing the Cre recombinase transgene (T-29-1), referred to as CamkIIα-Cre were kindly provided by Dr. S. Tonegawa (Tsien et al., 1996). PERK conditional knockout (cKO) and wild-type (WT) littermate control mice were on a C57/Bl6 genetic background that was backcrossed for more than 10 generations. For all molecular and behavioral experiments, adult mice two to five months of age were used, unless otherwise noted. Mice were maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use for Laboratory Animals from the NIH.

Genotyping

Genotyping of mice was performed using standard procedures. Please see Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

Western Blotting

Western blots were performed using standard procedures as described previously (Banko et al., 2005). Please see Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

Immunohistochemistry and Nissl Staining

Immunohistochemistry and Nissl staining were performed using standard procedures. Please see Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

SUnSET Technique

Proteins were labeled using an adaptation of the SUnSET method (Schmidt et al., 2009). Briefly, 400 µm coronal prefrontal slices from WT and PERK cKO mice were prepared using a vibratome, slices were allowed to recover in artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF) at 32°C for 1 hour and subsequently treated with puromycin (P8833, Sigma-Aldrich, 5µg/mL) for 45 mins. Reactions were stopped by flash freezing the slices on dry ice. Proteins were prepared, blotted, and quantified as described above (see Western blotting) and 50 µg of puromycin-labeled protein was resolved on 4–12% gradient gels (Invitrogen) and visualized using an antibody specific to puromycin (12D10, see Western blotting). Protein synthesis levels were determined by taking the total lane signal from 15 kDa to 250 kDa and subtracting the signal from the control lane that was not labeled by puromycin. Comparisons of protein synthesis levels between both genotypes were made by normalizing to the average WT signal obtained from different experimental replicates.

Polysome Analysis

Three pairs of 3-week-old PERK cKO mice and their wild-type littermates were terminally anesthetized by isoflurane and polysome gradients were prepared. Briefly, post-mitochondrial supernatants of prefrontal cortex, dissected free from white matter, were prepared and separated by sucrose density gradients (20%–50%). Gradients were centrifuged at 4°C for 2 hrs at 40,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor. Then, 890 µL fractions (16 per gradient) were collected with continuous monitoring of UV absorbance at 254 nm (UA-6 absorbance detector; ISCO).

Prepulse Inhibition

Sensorimotor gating was measured by testing the startle response and the prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the startle response. Mice were placed individually in a Plexiglas cylinder connected to a startle detector. Upon habituating to the background noise (70 dB), each mouse was presented with a semi-random series of prepulses of varying intensities (74, 78, 82, 86 and 90 dB) paired with an acoustic startle stimulus (120 dB). The % PPI was calculated as follows: [1 − (startle response to prepulse+pulse)/(startle response to pulse alone)] × 100.

Novel Object Recognition

Novel object recognition experiments were performed as previously described (Hoeffer et al., 2008). The novel object recognition task is based on the natural tendency of mice to explore a novel object rather than a familiar object. The amount of time spent exploring the novel object was divided by the total time spent exploring both objects to generate a preference index which was multiplied by 100 to calculate percent object preference. The Noldus EthoVision software and video tracking system was used to monitor and record object interaction time.

Morris Water Maze Reversal Learning Task

MWM experiments were performed as previously described (Banko et al., 2005) and the reversal learning protocol was adapted from previous studies (Hoeffer et al., 2008). Escape latency, number of previous platform position crossing, time spent in each quadrant, and trajectories of the mice were recorded with a computerized video tracking system (Noldus EthoVision). Briefly, the paradigm consisted of a 9-day training period broken into several phases. On days 1–5 (reference), mice were trained to locate a submerged hidden platform. Following completion of the last training trial on day 5, a single probe trial was given by removing the hidden platform from the pool. On days 6 and 7 (reversal), the originally learned platform location was moved to the opposite quadrant. On days 8 and 9 (visible), mice were tested using a visible cue. During reference, reversal and visible phases, mice were given 4 trials/day (60 s maximum, inter trial interval (ITI) 15 mins).

Y-water Maze Arm Reversal Task

Arm reversal in the Y-water maze task was carried out as described previously (Hoeffer et al., 2008). A retraining paradigm was incorporated to allow the 12 out of 13 PERK cKO mice that perseverated to make three consecutive correct choices (Figure 4A). This entailed using a plexiglas wall to section off the incorrect arm choice. Once three consecutive correct choices were made, the wall was removed and mice were tested to determine the latency to find the new escape location. For the immediate arm reversal task (Figure 4B), 4-month-old PERK cKO mice and their wild-type littermates were trained to locate an escape platform placed in one arm of the Y-maze with a slight modification. Following acquisition, the escape platform was switched on the same day (immediate) and the behavioral flexibility of the mice to learn the new escape location was measured.

Fear Extinction

Prior to extinction training, mice were fear conditioned by training them to associate two CS-US pairings separated by 1 min (foot-shock intensity (US): 0.65 mA, 2 s duration; tone (CS): 85 dB white noise, 30 s duration). The following day, mice were placed in an environmentally altered training chamber and received two extinction training sessions consisting of 15 consecutive CS presentations with an average intertrial interval between CSs of 120 seconds and a 24 hr interval between each session. 24 hrs after the last extinction training session (day 3), mice were returned to testing chamber and presented with an LTM test (2 tone alone trials). Freezing was recorded continuously during the 15 extinction training trials and 2-trial LTM test sessions. Freezing was scored blind with respect to the mouse genotype.

Intracellular Electrophysiology

Whole cell recordings from medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal cells from layer-II were conducted using standard procedures. Please see Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

Human Samples

Protein samples extracted from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC; Brodmann Area 46) of 35 individuals in each of the three diagnostic groups: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and unaffected controls were obtained from the Stanley Medical Research Institute Array Collection. These specimens were collected, with informed consent from next of kin, by participating medical examiners between January 1995 and June 2002. All groups were matched for age, sex and race. A summary of the relevant patient demographic information is provided (Table S1). The specimens were collected, processed and stored in a standardized way. Proteins were extracted using a protease inhibitor-Tris-glycerol extraction buffer (AEBSF 0.048%, aprotinin 0.01%, leupeptin 0.002%, pepstatin A 0.001%, glycerol 50%, Tris Ultra Pure 1.2%) (0.1 g brain tissue: 1.25 mL buffer). Analysis of 20 µg protein samples from schizophrenia (n = 35), bipolar (n = 35), and unaffected controls (n = 35) was conducted; the samples were coded such that the investigator was blind to diagnostic status. Upon decoding, no signal was detected in two samples from the schizophrenia cohort for the ATF4 analysis and eliminated from further analysis.

Pharmacological Reagents

For protein synthesis studies using the SUnSET technique (Figure 2A), coronal prefrontal slices from WT and PERK cKO mice were incubated with puromycin (P8833, Sigma-Aldrich, 5µg/mL) for 45 mins. For NMDA hypofunction studies (Figures 5C and 5D), C57/Bl6 wild-type mice were given either a single (acute) or 15 daily (chronic) i.p. injection(s) of vehicle (0.9% saline) or MK-801 dissolved in vehicle (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; 0.2 mg/kg for acute studies and 0.1 mg/kg for chronic studies). SSR504734, a glycine transporter-1 inhibitor compound, was provided by Sanofi-Aventis (Paris, France) and dissolved in water with a few drops of Tween-80 as previously described (Depoortere et al., 2005). For behavioral and molecular rescue studies (Figure 6), injections of SSR504734 (20 mg/kg) were given i.p. to PERK cKO and wild-type littermates for 21 days prior to behavioral testing and protein expression analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses between two groups were performed by using a two-tailed Student's t test. Comparisons involving drug treatment, time courses or protein expression among multiple groups or genotypes were performed with a one or two-way ANOVA. For the human studies, potential association of continuous variables such as age, brain pH, post-mortem interval (PMI) and lifetime antipsychotic usage was determined using Spearman correlation coefficients. Significance criteria of p<0.05 was used for all data analysis. Extreme outliers were detected by applying Grubbs’ method with α = 0.05 to each experimental group and eliminated from further analysis (GraphPad software).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

PERK, p-eIF2α, and ATF4 levels are reduced in the prefrontal cortex of PERK cKO mice

PERK cKO mice exhibit deficits in behavioral flexibility

Molecular and cognitive deficits in PERK cKO mice are reversed by a GlyT1 inhibitor

PERK and ATF4 levels are reduced in the frontal cortex of schizophrenic patients

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Tonegawa for providing CamkIIα-Cre mice; Dr. M. Webster and the Stanley Medical Research Institute for generously donating the human brain samples; Drs. O.E. Bergis and D. Boulay from Sanofi-Aventis for providing the SSR504734 compound and Drs. J.C. Darnell, R.B. Darnell and S. Van Driesche for providing advice, expertise and reagents for the polysome experiments. This research was supported by the NIH grants NS034007 and NS047384 and the FRAXA Research Foundation awarded to E.K and the NRSA Predoctoral Fellowship Training Grant F31 NS063686 and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation scholarship awarded to M.A.T.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

The study was directed by E.K. and conceived and designed by M.A.T. and E.K. M.A.T. conducted the molecular, behavioral, and pharmacological experiments. H.K. designed and performed the electrophysiology experiments and provided conceptual advice for the project. D.R.C. contributed the PerkloxP mice. R.C.W. provided the anti-ATF4 antibody. P.P. contributed the anti-puromycin (12D10) antibody. The manuscript was written by M.A.T. and E.K. and edited by all of the authors.

References

- Abdul-Monim Z, Reynolds GP, Neill JC. The effect of atypical and classical antipsychotics on sub-chronic PCP-induced cognitive deficits in a reversal-learning paradigm. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel T, Martin KC, Bartsch D, Kandel ER. Memory suppressor genes: inhibitory constraints on the storage of long-term memory. Science. 1998;279:338–341. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auluck PK, Caraveo G, Lindquist S. alpha-Synuclein: membrane interactions and toxicity in Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:211–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banko JL, Poulin F, Hou L, DeMaria CT, Sonenberg N, Klann E. The translation repressor 4E-BP2 is critical for eIF4F complex formation, synaptic plasticity, and memory in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9581–9590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2423-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch D, Ghirardi M, Skehel PA, Karl KA, Herder SP, Chen M, Bailey CH, Kandel ER. Aplysia CREB2 represses long-term facilitation: relief of repression converts transient facilitation into long-term functional and structural change. Cell. 1995;83:979–992. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belforte JE, Zsiros V, Sklar ER, Jiang Z, Yu G, Li Y, Quinlan EM, Nakazawa K. Postnatal NMDA receptor ablation in corticolimbic interneurons confers schizophrenia-like phenotypes. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:76–83. doi: 10.1038/nn.2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsios P, Giakoumaki SG, Theou K, Frangou S. Increased prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response is associated with better strategy formation and execution times in healthy males. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2494–2499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MD, Varty GB, Arad M, Barak S, De Levie A, Boulay D, Pichat P, Griebel G, Weiner I. Procognitive and antipsychotic efficacy of glycine transport 1 inhibitors (GlyT1) in acute and neurodevelopmental models of schizophrenia: latent inhibition studies in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202:385–396. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. J Affect Disord. 2009;113:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:234–258. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Muzzio IA, Malleret G, Bartsch D, Verbitsky M, Pavlidis P, Yonan AL, Vronskaya S, Grody MB, Cepeda I, et al. Inducible enhancement of memory storage and synaptic plasticity in transgenic mice expressing an inhibitor of ATF4 (CREB-2) and C/EBP proteins. Neuron. 2003;39:655–669. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb JE, Bradshaw NJ, Soares DC, Porteous DJ, Millar JK. The DISC locus in psychiatric illness. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:36–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Gobert D, Harding H, Herdy B, Azzi M, Bruno M, Bidinosti M, Ben Mamou C, Marcinkiewicz E, Yoshida M, et al. Translational control of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by the eIF2alpha kinase GCN2. Nature. 2005;436:1166–1173. doi: 10.1038/nature03897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Gobert D, Stern E, Gamache K, Colina R, Cuello C, Sossin W, Kaufman R, Pelletier J, Rosenblum K, et al. eIF2alpha phosphorylation bidirectionally regulates the switch from short- to long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2007;129:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2009;61:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delepine M, Nicolino M, Barrett T, Golamaully M, Lathrop GM, Julier C. EIF2AK3, encoding translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3, is mutated in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;25:406–409. doi: 10.1038/78085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depoortere R, Dargazanli G, Estenne-Bouhtou G, Coste A, Lanneau C, Desvignes C, Poncelet M, Heaulme M, Santucci V, Decobert M, et al. Neurochemical, electrophysiological and pharmacological profiles of the selective inhibitor of the glycine transporter-1 SSR504734, a potential new type of antipsychotic. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1963–1985. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey S, Baird TD, Zhou D, Palam LR, Spandau DF, Wek RC. Both transcriptional regulation and translational control of ATF4 are central to the integrated stress response. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33165–33174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix S, Gilmour G, Potts S, Smith JW, Tricklebank M. A within-subject cognitive battery in the rat: differential effects of NMDA receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:227–242. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goos LM, Crosbie J, Payne S, Schachar R. Validation and extension of the endophenotype model in ADHD patterns of inheritance in a family study of inhibitory control. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:711–717. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08040621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Jungries R, Chung P, Plesken H, Sabatini DD, Ron D. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffer CA, Klann E. mTOR signaling: at the crossroads of plasticity, memory and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffer CA, Tang W, Wong H, Santillan A, Patterson RJ, Martinez LA, Tejada-Simon MV, Paylor R, Hamilton SL, Klann E. Removal of FKBP12 enhances mTOR-Raptor interactions LTP memory, and perseverative/repetitive behavior. Neuron. 2008;60:832–845. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:113–127. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC. Glycine transport inhibitors and the treatment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Belforte JE, Lu Y, Yabe Y, Pickel J, Smith CB, Je HS, Lu B, Nakazawa K. eIF2alpha Phosphorylation-dependent translation in CA1 pyramidal cells impairs hippocampal memory consolidation without affecting general translation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2582–2594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3971-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julier C, Nicolino M. Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialog between genes and synapses. Biosci Rep. 2001;21:565–611. doi: 10.1023/a:1014775008533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Bear MF. The autistic neuron: troubled translation? Cell. 2008;135:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Govindarajan A, Tonegawa S. Translational regulatory mechanisms in persistent forms of synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2004;44:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, Heninger GR, Bowers MB, Jr, Charney DS. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesh TA, Niendam TA, Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: mechanisms and meaning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:316–338. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CM, Levinson DF, Wise LH, DeLisi LE, Straub RE, Hovatta I, Williams NM, Schwab SG, Pulver AE, Faraone SV, et al. Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part II: Schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:34–48. doi: 10.1086/376549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Coyle JT, Green RW, Javitt DC, Benes FM, Heckers S, Grace AA. Circuit-based framework for understanding neurotransmitter and risk gene interactions in schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Hendershot LM. Delineation of a negative feedback regulatory loop that controls protein translation during endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34864–34873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP, Ron D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory--a century of consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JA, Kandpal G, Ma L, Austin CP. DISC1 (Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1) is a centrosome-associated protein that interacts with MAP1A, MIPT3, ATF4/5 and NUDEL: regulation and loss of interaction with mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1591–1608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowry BJ, Holmans PA, Pulver AE, Gejman PV, Riley B, Williams NM, Laurent C, Schwab SG, Wildenauer DB, Bauche S, et al. Multicenter linkage study of schizophrenia loci on chromosome 22q. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:784–795. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir WJ, Pickard BS, Blackwood DH. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:140–147. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Zsiros V, Jiang Z, Nakao K, Kolata S, Zhang S, Belforte JE. GABAergic interneuron origin of schizophrenia pathophysiology. Neuropharmacology. 2011;62:1574–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan U, Ozcan L, Yilmaz E, Duvel K, Sahin M, Manning BD, Hotamisligil GS. Loss of the tuberous sclerosis complex tumor suppressors triggers the unfolded protein response to regulate insulin signaling and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2008;29:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Mucke L. Amyloid-beta-induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: from synapses toward neural networks. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:812–818. doi: 10.1038/nn.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu M, Tang F, Wang L, Yan H, Han Y, Yan J, Yue W, Zhang D. Associations of ATF4 gene polymorphisms with schizophrenia in male patients. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:732–736. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis AF, Kannengiesser C, Jennane F, Manna TD, Cheurfa N, Oudin C, Savoldelli RD, Oliveira C, Grandchamp B, Kok F, et al. Two novel mutations in the EIF2AK3 gene in children with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:187–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD, Klann E. Making synaptic plasticity and memory last: mechanisms of translational regulation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.1735809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Cabezas O, Patch AM, Minton JA, Flanagan SE, Edghill EL, Hussain K, Balafrej A, Deeb A, Buchanan CR, Jefferson IG, et al. Wolcott-Rallison syndrome is the most common genetic cause of permanent neonatal diabetes in consanguineous families. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4162–4170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Ge H, Ren K, Pena de Ortiz S, Quirk GJ. Consolidation of fear extinction requires protein synthesis in the medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5704–5710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0786-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Klann E. Dysregulated mTORC1-Dependent Translational Control: From Brain Disorders to Psychoactive Drugs. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5:76. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura N, Ando T, Maruyama Y, Fujimuro M, Mochizuki H, Honjo K, Shimoda M, Toda H, Sawamura-Yamamoto T, Makuch LA, et al. Nuclear DISC1 regulates CRE-mediated gene transcription and sleep homeostasis in the fruit fly. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:1138–1148. 1069. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:275–277. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senee V, Vattem KM, Delepine M, Rainbow LA, Haton C, Lecoq A, Shaw NJ, Robert JJ, Rooman R, Diatloff-Zito C, et al. Wolcott-Rallison Syndrome: clinical, genetic, and functional study of EIF2AK3 mutations and suggestion of genetic heterogeneity. Diabetes. 2004;53:1876–1883. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer P, Feldon J, Yee BK. The glycine transporter 1 inhibitor SSR504734 enhances working memory performance in a continuous delayed alternation task in C57BL/6 mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202:371–384. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Ozonoff SJ, Ursu S, Ravizza S, Cummings N, Ly S, Carter CS. The neural substrates of cognitive control deficits in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2515–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Dever TE. Eukaryotic translation initiation factors and regulators. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:56–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotres-Bayon F, Bush DE, LeDoux JE. Emotional perseveration: an update on prefrontal-amygdala interactions in fear extinction. Learn Mem. 2004;11:525–535. doi: 10.1101/lm.79504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Weber M, Qu Y, Light GA, Braff DL. Realistic expectations of prepulse inhibition in translational models for schizophrenia research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:331–388. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton CM, Carson DJ, Stewart FJ. Autopsy findings in the Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1997;17:487–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Chen DF, Gerber D, Tom C, Mercer EH, Anderson DJ, Mayford M, Kandel ER, Tonegawa S. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell. 1996;87:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Norton N, Williams H, Ekholm B, Hamshere ML, Lindblom Y, Chowdari KV, Cardno AG, Zammit S, Jones LA, et al. A systematic genomewide linkage study in 353 sib pairs with schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1355–1367. doi: 10.1086/380206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin JC, Wallach JS, Del Vecchio M, Wilder EL, Zhou H, Quinn WG, Tully T. Induction of a dominant negative CREB transgene specifically blocks long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:49–58. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, McGrath B, Li S, Frank A, Zambito F, Reinert J, Gannon M, Ma K, McNaughton K, Cavener DR. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3864-3874.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu PJ, Huang W, Kalikulov D, Yoo JW, Placzek AN, Stoica L, Zhou H, Bell JC, Friedlander MJ, Krnjevic K, et al. Suppression of PKR Promotes Network Excitability and Enhanced Cognition by Interferon-gamma-Mediated Disinhibition. Cell. 2011;147:1384–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.