Abstract

Although immunological detection of proteins is used extensively in retinal development, studies are often impeded because antibodies against crucial proteins cannot be generated or are not readily available. Here, we overcome these limitations by constructing genetically engineered alleles for Math5 and Pou4f2, two genes required for retinal ganglion cell (RGC) development. Sequences encoding a peptide epitope from haemagglutinin (HA) were added to Math5 or Pou4f2 in frame to generate Math5HA and Pou4f2HA alleles. We demonstrate that the tagged alleles recapitulated the wild-type expression patterns of the two genes, and that the tags did not interfere with the function of the cognate proteins. In addition, by co-staining, we found that Math5 and Pou4f2 were transiently co-expressed in newly-born RGCs, unequivocally demonstrating that Pou4f2 is immediately downstream of Math5 in RGC formation. The epitope-tagged alleles provide new and useful tools for analyzing gene regulatory networks underlying RGC development.

Keywords: Math5, Pou4f2, tagged knock-in alleles, retinal ganglion cell development, gene regulatory networks

Introduction

Protein detection has been and continues to be crucial for advancing our understanding of retinal development, function and disease. Of constant frustration to investigators, however, is the generation of high quality antibodies against specific proteins, which is highly unpredictable and inherently problematic. A widely used method that circumvents direct antibody production is to fuse short, immunoreactive peptide epitopes to protein sequences (Kimple and Sondek, 2002; Terpe, 2003). Epitope tags that are most commonly used include myc, FLAG, and hemagglutinin (HA). These epitope tags are generally applicable for experiments that rely on manipulating tissue culture cells, where exogenous DNA constructs can be readily introduced. Epitope-tagging proteins in intact animals, such as mice, have only recently been attempted (Vokes et al., 2008). Unlike epitope-tagging in tissue culture cells, generating eptope-tagged alleles using in vivo gene targeting is labor intensive, time consuming, and carries with it a substantial degree of uncertainty. For example, subtle disruptions of function that are not easily detectable in cell culture may have deleterious effects on the development and health of the live animal. A convincing demonstration that the fused epitope tag does not interfere with the in vivo function of the cognate protein is therefore a critical element in any strategy aimed at creating epitope-tagged alleles.

Here, we report the generation of HA-tagged alleles for Math5 (also known as Atoh7 ) and Pou4f2 (also known as Brn3b ), which encode transcription factors that are essential for the development of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). RGCs are one of seven retinal cell types that are derived from a single population of retinal progenitor cells during development (Livesey and Cepko, 2001; Mu and Klein, 2004). Math5 is a proneural gene homologous to the Drosophila gene Atonal and encodes a bHLH transcription factor (Brown et al., 1998). Math5 is absolutely required for RGC fate; knockout of Math5 leads to failure of RGC formation (Brown et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001). Pou4f2 is a class IV POU domain transcription factor functioning downstream of Math5 (Xiang et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2000; Mu et al., 2005a). Pou4f2 is activated immediately after Math5-expressing progenitor cells commit to an RGC fate; however, the extent to which these two genes overlap in expression in individual retinal cells is not known. Pou4f2 is not required for the initial birth of RGCs, but for their differentiation; RGCs in Pou4f2-null embryos are normally specified but most of them eventually undergo apoptosis (Gan et al., 1999), because of defects in RGC integrity, migration, axon formation, and axon pathfinding (Wang et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2002). Math5 and Pou4f2 exert their functions by regulating downstream genes in the gene regulatory network (GRN) for RGC development. The RGC GRN is a hierarchically interconnected network in which several different transcription factors are positioned at key nodes (Mu et al., 2004; Mu et al., 2005a; Mu et al., 2008). Math5 is genetically upstream of Pou4f2 and Isl1, a LIM-homeodomain transcription factor, and renders retinal progenitor cells competent for assuming RGC fate. Pou4f2 and Isl1 function immediately following the birth of RGCs and activate sets of genes essential for differentiation. Pou4f2 and Isl1 regulate two distinct but overlapping sets of genes and define two different gene regulation branches downstream of Math5.

A full understanding of the RGC GRN requires knowledge of the means by which individual transcription factors regulate their targets and interact with other factors to achieve precise regulation. Math5 mRNA is expressed in a subset of retinal progenitor cells (Brown et al., 1998). Unfortunately, useful antibodies against Math5 are not currently available. This has greatly hindered further characterization of Math5’s role in RGC development. Although commercial antibodies are available for Pou4f2, their quality varies considerably and their value is untested in many applications. To circumvent these problems, we used gene targeting to generate knock-in HA-tagged alleles for Math5 and Pou4f2, namely Math5HA and Pou4f2HA respectively. We show that the HA-tagged alleles are fully functional and use them to investigate the spatial relationships of Math5 and Pou4f2 in the developing retina. These two alleles thus provide new and useful tools for further analysis of the RGC GRN.

Results

Generation of tagged Math5 and Pou4f2 alleles by gene targeting

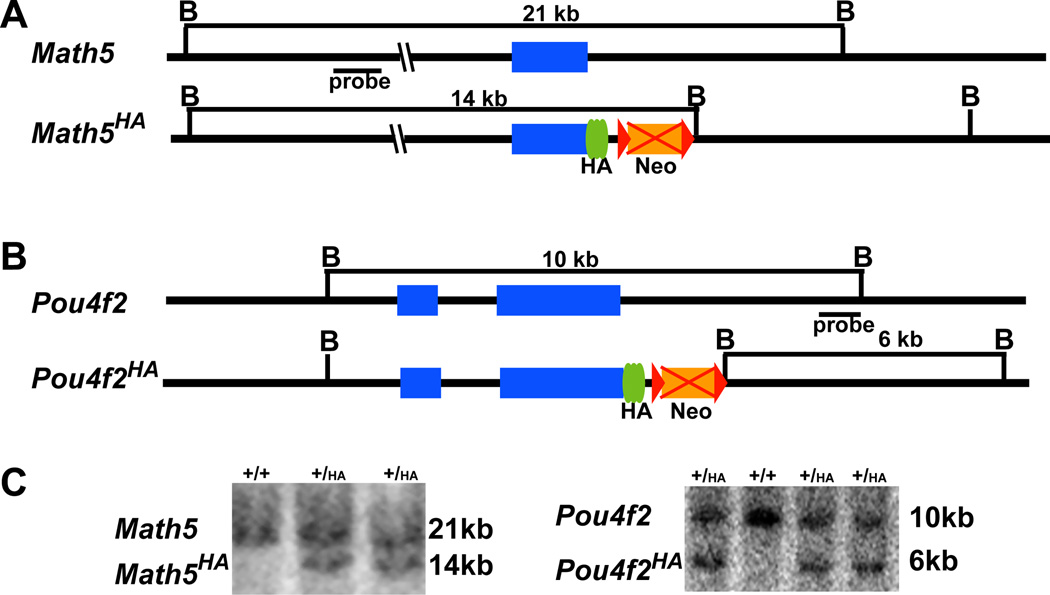

Our goal was to use gene targeting to create modified alleles for Math5 and Pou4f2 that would circumvent the need for antibody production from synthetic peptides or bacterially-produced protein antigens and could be useful for monitoring protein expression in RGC development. In designing our strategy, a major concern was to ensure that epitope-tagged proteins did not interfere with the function of the cognate proteins. Both Math5 and Pou4f2 are conserved in all animal species examined so far; the highest conserved region in Math5 is the bHLH region and in Pou4f2, the POU-homeodomain. Comparison of Math5 and Pou4f2 with their respective orthologs from different species suggested that these two families of proteins are highly variable at the C-terminal regions, suggesting that these regions are not critical for function. We therefore decided to tag the C-terminal portion of Math5 and Pou4f2; sequences encoding three copies of HA tags were added in frame immediately after the final codons (Fig. 1A, B). Thus, the final protein products for the two engineered alleles would contain a full-length Math5 or Pou4f2 with three HA tags at their C-terminus. Mouse ES cells harboring the targeted alleles were successfully generated following electroporation as shown by Southern hybridization with external probes (Fig. 1C). Targeted Math5HA and Pou4f2HA ES cells were used for blastocyst injections and germline transmission. The Neo cassettes in the two targeting constructs were flanked by two loxP sites to eventually delete the cassettes using a transgenic line constitutively expressing Cre (Schwenk et al., 1995). This meant that only minor changes were introduced into the original alleles of both Math5HA and Pou4f2HA (Fig. 1A, B), thereby minimizing the chances of the essential cis elements being disrupted. The resulting Math5HA/HA and Pou4f2HA/HA mice were viable, fertile, and behaved normally throughout postnatal and adult life.

Figure 1.

Generation of epitope-tagged alleles. (A) Structures of wild-type Math5 and Math5HA alleles. Sequences encoding three copies of HA tag were fused in frame with the coding region of Math5 in Math5HA. (B) Structures of wild-type Pou4f2 and Pou4f2HA alleles. In diagrams of A and B, blue boxes are coding regions, green ovals are HA tags, brown boxes are Neo cassettes (eventually deleted by crossing with the CMV-Cre line as indicated by the red crosses), and red triangles are loxP sites. B is a restriction site for BamH I. Positions of external probes and the sizes of DNA fragments that are recognized in different alleles are indicated. (C) Southern blot hybridization to identify ES cell clones harboring the targeted alleles. Wild-type (+) and targeted bands (HA) for each allele are indicated. Positive clones have two bands.

Math5HA and Pou4f2HA recapitulate the retinal expression patterns of their respective endogenous genes

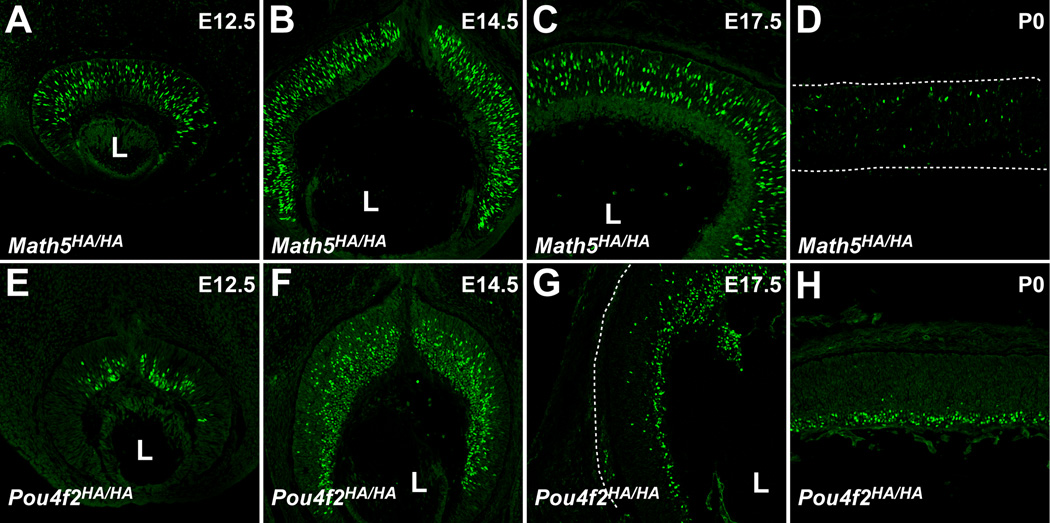

To examine whether Math5HA and Pou4f2HA was expressed from the HA-tagged alleles and recognized by anti-HA antibodies, we performed immunofluorescence labeling on retinal sections from mouse embryos from different developmental stages. Previous in situ hybridization analyses showed that Math5 transcripts were expressed in a subset of progenitor cells, but not in RGCs, from embryonic day (E) 11 through postnatal day (P) 0 (Brown et al., 1998). Consistent with this, we observed HA-positive cells only in the neuroblast layer, but not in RGCs, of Math5HA/HA retinas from E12.5 to P0 (Fig. 2A–D). Likewise, as with the expression patterns of Math5 transcripts, Math5HA, only a subset of cells in the neuroblast layer expressed Math5 (Fig. 2A–D). Temporally, Math5HA expression also paralleled that of the Math5 transcripts; it reached the peak at E14.5 (Fig. 2B), reduced to residual levels in labeled cells at P0 (Fig. 2D), and diminished afterwards (data not shown). Although we could not compare Math5HA with Math5 due to lack of either an antibody or riboprobe that specifically recognize only the wild-type protein, these results nonetheless strongly indicated that Math5HA faithfully recapitulated the expression patterns of the wild-type Math5 allele in the retina. Although we did not assess whether the HA tag affected protein stability, the strong correlation of Math5 transcript and Math5HA protein patterns indicated the effects were likely to be insignificant.

Figure 2.

Protein products from Math5HA and Pou4f2HA alleles are recognized by an anti-HA antibody and show the expected expression patterns. (A–D) Anti-HA antibody staining (green) of Math5HA/HA retinas from four developmental stages identifies the RGC competent progenitor cells scattered throughout the progenitor cell layer but not in the GCL. At P0, only residual Math5HA-positive cells were detected. The patterns were consistent with previously reported mRNA expression of Math5. (E-H) Anti-HA antibody recognizes RGCs on Pou4f2HA/HA retinal sections from E12.5 to P0. At early stages from E12.5-E17.5, Pou4f2HA-positive cells include newly-formed RGCs still located in the progenitor cell layer and those that have migrated to the GCL. At P0, RGCs were located mostly in the GCL. The patterns are identical to previous reports with an anti-Pou4f2 antibody. The background of the images was brought up intentionally to show the outlines of the retinas; in D and G, the outlines are indicated by dotted lines. L indicates the position of the lens.

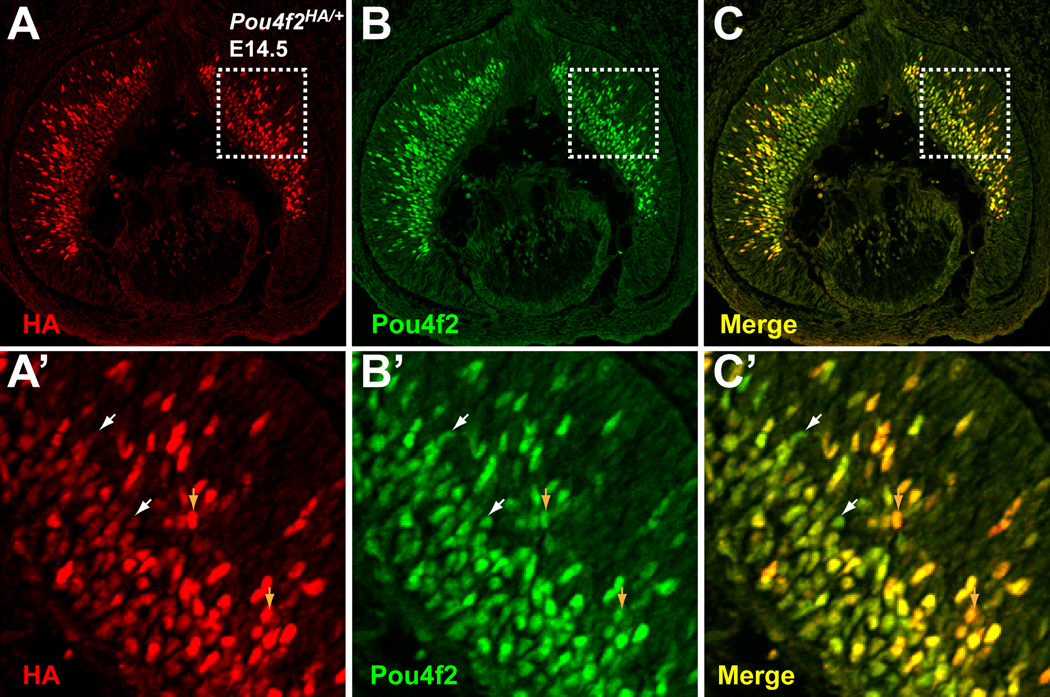

Pou4f2 is expressed at the birth of RGCs and therefore is one of the earliest RGC markers. In the retina, it is first detected at E11.5 when the first RGCs are born and its expression continues throughout adulthood (Xiang et al., 1995). From E11.5 to E17.5, Pou4f2 can be detected both in newly born RGCs, which are still located in the neuroblast layer and mingle with retinal progenitor cells, and RGCs that have already migrated to the ganglion cell layer (GCL). Consistent with these patterns, we detected Pou4f2HA both in the neuroblast layer and the GCL on Pou4f2HA/HA retinas at E12.5, E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 2 E–G), but only in the GCL at P0 (Fig. 2H). To further confirm that Pou4f2HA expression mirrored the wild-type gene, we performed co-staining with anti-HA and anti-Pou4f2 antibodies on Pou4f2HA/+ retinal sections at E14.5. An anti-Pou4f2 antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology did not recognize Pou4f2HA (data not shown), possibly because the HA tag fused to Pou4f2 disrupted the epitope recognized by the antibody. Thus, the two antibodies specifically recognized protein products from the two alleles, respectively. We found that Pou4f2 and Pou4f2HA had essentially identical expression patterns; in both the neuroblast layer and the GCL, positive cells always expressed both proteins (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we observed a large degree of variation in the expression levels of these two alleles (Fig. 3A’–C’), not only among different RGCs, but also within single cells; some RGCs express more Pou4f2 than Pou4f2HA, while others the reverse. This may reflect a natural stochastic fluctuation in Pou4f2 expression. These results indicated that the normal regulatory mechanism was not disrupted in Pou4f2HA.

Figure 3.

Expression patterns from Pou4f2HA and Pou4f2 are identical. Anti-HA and anti-Pou4f2 were used to stain E14.5 retinal sections by immunoflourescence. Red is HA, green is Pou4f2. A’–C’ are high magnifications of the boxed areas in A-C. Patterns from the two antibodies overlap completely. White arrowheads indicate cells that have higher levels of Pou4f2 than Pou4f2HA and brown arrowheads point to cells with higher levels of Pou4f2HA than Pou4f2.

Math5HA and Pou4f2HA alleles are fully functional in RGC development

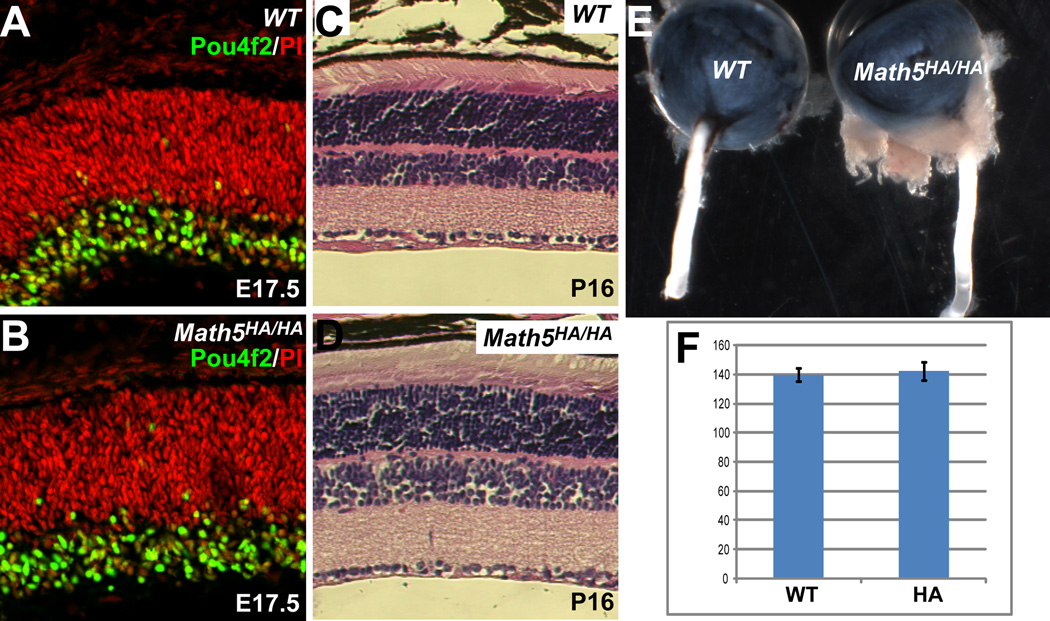

To determine whether Math5HA retained full function in RGC development, we examined retinal development in Math5HA/HA embryos. If the function of Math5HA was compromised by the HA tag, Math5HA/HA retinas would be similar to Math5-null retinas (Brown et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001) and few RGCs would form. Using Pou4f2 as a marker for RGC differentiation, we found that RGCs readily formed in Math5HA/HA retinas (Fig. 4A, B) and there was no significant difference in RGC numbers between Math5HA/HA and wild-type retinas at E17.5 (Fig. 4F). Histological analysis of mature Math5HA/HA retinas did not reveal any detectable defects as compared to wild-type retinas. (Fig. 4C, D). In addition, unlike Math5-null mice, which lack optic nerves (Brown et al., 2001), the optic nerves from Math5HA/HA mice were of normal size when compared to those from wild-type animals (Fig. 4E). These results clearly indicated that Math5HA was fully functional in promoting RGC development.

Figure 4.

Math5HA is fully functional in promoting RGC development. (A, B) Anti-Pou4f2 antibody staining (green) shows that there are similar numbers of RGCs in wild-type (WT) and Math5HA/HA retinas at E17.5. Red is nuclear staining by PI. (C, D) H&E staining indicates that mature Math5HA/HA retinas (P16) have normal structures as compared to those of wild-type controls. Note that there is no obvious change of cell numbers in the GCL of Math5HA/HA retinas. (E) Math5HA/HA mice have normal-sized optic nerves as compared to the wild-type. (F) Cell counting indicates that there is no significant difference in the number of RGCs between wild-type and Math5HA/HA retinas at E17.5 (n=4, p=0.28). Y axis is number of cells per arbitrary length unit.

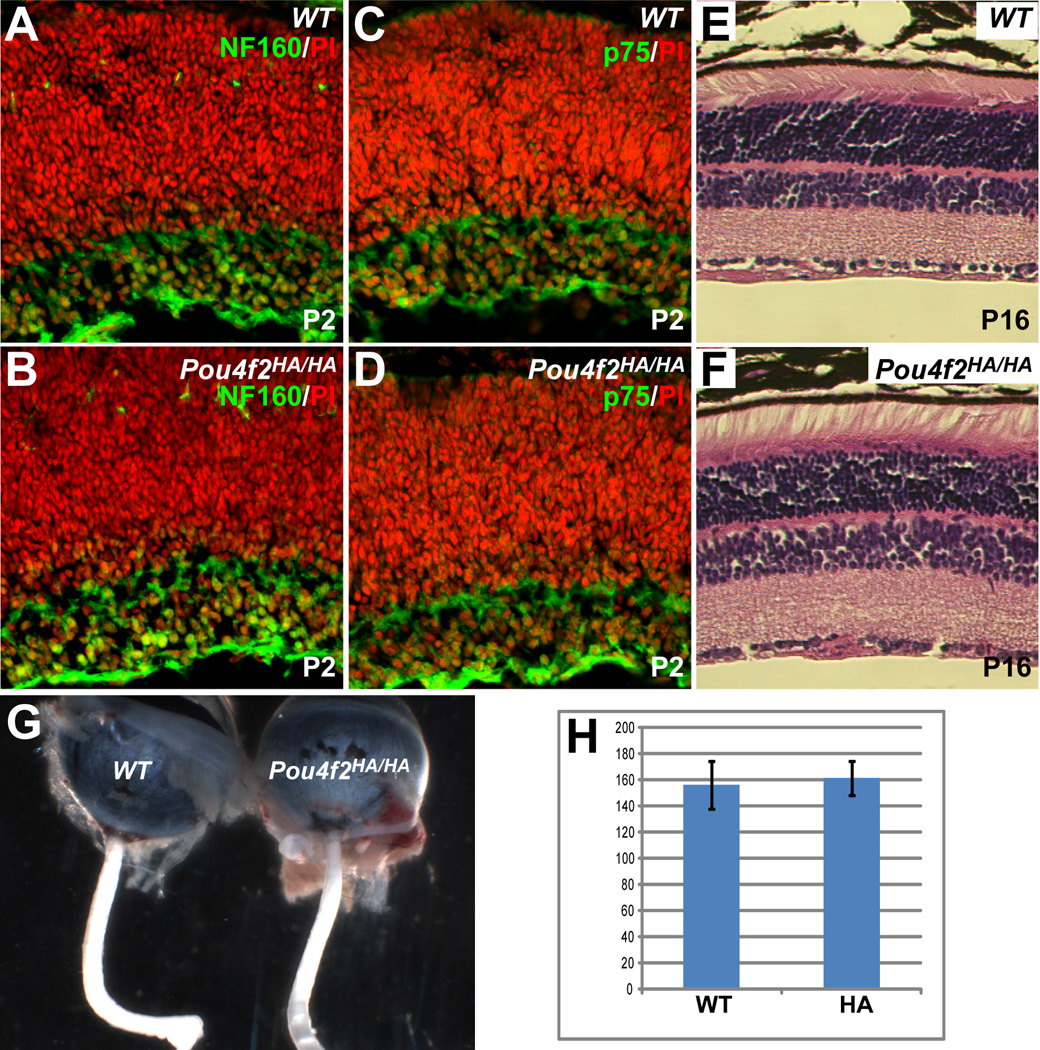

Similarly, we examined RGC development in Pou4f2HA/HA retinas.Pou4f2-null retinas initially have normal numbers of RGCs but most eventually undergo apoptosis due to aberrant differentiation (Erkman et al., 1996; Gan et al., 1996; Gan et al., 1999). If the Pou4f2HA allele was dysfunctional, Pou4f2HA/HA retinas would be expected to have decreased numbers of RGCs at stages after E17.5 (Gan et al., 1999). Immunostaining of P2 Pou4f2HA/HA retinal sections with RGC markers, NF160 and p75, showed no detectable change in either the intensities of the two markers or number of positive cells as compared to that in wild-type retinas (Fig. 5A–D). The total number of cells in the GCL was not significantly different in Pou4f2HA/HA and wild-type retinas (Fig. 5H). Unlike optic nerves of Pou4f2-null mice (Gan et al., 1999), the optic nerves of Pou4f2HA/HA mice were normal in size (Fig. 5G). No overt morphological abnormalities were observed in any of the nuclear or plexiform layers in the mature retinas of Pou4f2HA/HA mice (Fig. 5E, F).

Figure 5.

RGCs develop normally in Pou4f2HA/HA mice. (A–D) Staining for two RGC markers, NF160 and p75 (green), at P2 revealed that there was no obvious change in the numbers of RGCs or expression levels of the two proteins in Pou4f2HA/HA retinas. Red is nuclear staining by PI. (E, F) H&E staining shows that mature (P16) Pou4f2HA/HA retinas have normal structures as compared to wild-type (WT); the cell numbers in all three layers are comparable with those of wild-type controls. (G) The optic nerves of Pou4f2HA/HA mice are not reduced in size compared to the wild-type. (H) No significant difference is seen in the total numbers of cells between the GCLs of Pou4f2HA/HA and wild-type mice at P2 (n=4, p=0.34). Y axis is number of cells per arbitrary length unit.

The results indicated that both Math5HA and Pou4f2HA function normally in RGC development. Any disruptions in Math5 and Pou4f2 function by the introduction of the HA tags were negligible.

Math5 and Pou4f2 are transiently co-expressed in RGC precursors

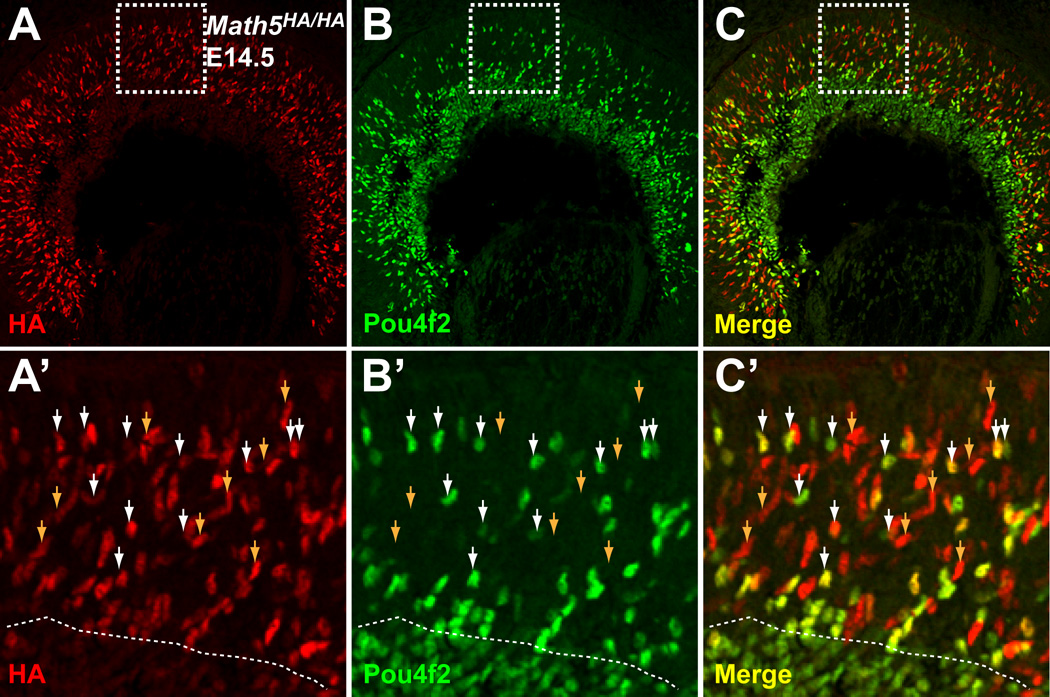

Although it has been established that Math5 and Pou4f2 are essential for RGC development and that Math5 functions genetically upstream of Pou4f2, the precise relationship between Math5 and Pou4f2 is unknown. Specifically, it is not known whether Math5 and Pou4f2 are co-expressed in the same cells at any point of RGC development and whether Math5 regulates Pou4f2 expression directly. In situ hybridization analyses have shown that Math5 and Pou4f2 are expressed in two largely separate but overlapping domains; Math5 confined to the neuroblast layer, and Pou4f2 in the GCL as well as the neuroblast layer. However, those studies did not provide unequivocal evidence to support the hypothesis that Math5 and Pou4f2 are expressed in the same cells. The Math5HA allele makes it possible to address this question. We performed co-labeling with anti-HA and anti-Pou4f2 antibodies with E14.5 Math5HA/HA retinal sections. As shown above, Math5HA expression was confined to the neuroblast layer, whereas Pou4f2 was expressed in all cells in the GCL and a subset of cells of the neuroblast layer (Fig. 6A–C). Cells expressing both Math5HA and Pou4f2 were clearly observed in the neuroblast layer (Fig. 6A–C). A closer examination of individual positive cells revealed that essentially all Pou4f2-positive cells in the neuroblast layer were also positive for Math5HA, but many (~50%) Math5HA cells did not express Pou4f2 (Fig. 6A’–C’). Cells positive for both Math5HA and Pou4f2 were found more frequently near the boundary between the neuroblast layer and the GCL. In the GCL, Pou4f2, but not Math5HA, was expressed. These results are consistent with a previous report that not all Math5-expressing cells adopt an RGC fate (Yang et al., 2003). More importantly, they indicate that Math5 and Pou4f2 are co-expressed in the same cells at the stage when the RGC fate is being committed. As the newly born RGCs migrated to the GCL and differentiated, Math5 expression diminished but Pou4f2 expression persisted.

Figure 6.

Math5 and Pou4f2 overlap transiently in expression during RGC development. Immunofluorescence labeling was performed on E14.5 Math5HA/HA sections with anti-HA (red) and anti-Pou4f2 (green) antibodies. Math5HA is restricted to the neuroblast layer and Pou4f2-positive cells are seen in both the neuroblast layer and the GCL. A’–C’ are high magnifications of the boxed areas in A–C. Dotted lines in A’–C’ mark the boundary between the neuroblast layer and the GCL. In the neuroblast layer, essentially all Pou4f2-positive cells were also Math5HA positive (some indicated by white arrowheads), whereas some Math5HA-positive cells were Pou4f2-negative (indicated by brown arrowheads). The double positive cells are in a transition stage from competent progenitor cells to fate-committed RGCs.

Discussion

Generating epitope-tagged alleles in vivo by gene targeting

The advantage of using gene targeting to generate epitope-tagged alleles, especially when compared to more conventional transgenic approaches, is that the epitope-tagged gene is inserted into the endogenous locus and prior knowledge of the gene promoters is not required. Gene targeting also avoids position and copy-number effects of transgenes that frequently cause deviations from endogenous gene expression (Robertson et al., 1995; Garrick et al., 1996; Sternfeld et al., 1998). Gene targeting thus ensures that the modified genes accurately reflect endogenous expression patterns and transcript levels. Both Math5HA and Pou4f2HA faithfully recapitulated the expression of their respective wild-type genes. A major concern of modifying genes by adding epitope tags is that the tags may interfere with the function of the cognate proteins, which may lead to undesired consequences and complicate interpretation of results. Our results suggest that adding the epitope tags to the highly variable C-terminal portions of both proteins avoids this caveat. This strategy proved successful for both Math5HA and Pou4f2HA alleles, as the HA-tags did not interfere their functions and RGCs in homozygous Math5HA/HA or Pou4f2HA/HA mice developed normally. Although in this study we used only the HA-tag, other tags fused to the C-termini of Math5 and Pou4f2 are likely to be successful as well.

Potential applications of epitope-tagged Math5 and Pou4f2 alleles

The two alleles described here offer new tools for studying retinal development, particularly the development of RGCs. For example, generating the Math5HA allele enabled us to visualize the expression pattern of the Math5 protein during retinal development for the first time. The alleles are also useful for protein co-expression studies, as we have demonstrated with Math5 and Pou4f2. A variety of anti-HA antibodies raised in different species are available, providing much flexibility for co-expression analyses using Math5 or Pou4f2 in conjunction with other retinal proteins.

The HA-tagged alleles for both Math5 and Pou4f2 should also be valuable tools for identifying interacting retinal proteins in vivo using antibody affinity purification in combination with mass spectrometry (Kimple and Sondek, 2002; Terpe, 2003). Very little is known about the proteins that interact with Math5 and Pou4f2, largely because robust antibodies suited for affinity purification have not been available.

A central interest for retinal development is to understand the structure and dynamics of GRNs involved in the formation of individual retinal cell types. Since Math5 and Pou4f2 occupy two of the key nodes in the RGC GRN, a further understanding of their functions requires knowledge of all the direct target genes they regulate. ChIP-seq technology, which combines chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with massive parallel sequencing (seq) can identify in vivo target genes of transcription factors on a genome-wide scale (Barski et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2007; Robertson et al., 2007). ChIP-seq has been successfully used to identify the target genes for a number of transcription factors. A prerequisite for a successful application of ChIP-seq is the availability of high-quality antibodies. The Math5HA and Pou4f2HA alleles should enable investigators to perform ChIP-seq analysis with anti-HA and identify in vivo target genes of these two transcription factors in the developing retina.

Genetic relationship between Math5 and Pou4f2

We further demonstrated the usefulness of these tagged alleles by analyzing the overlap of Math5 and Pou4f2 expression in RGC development. For the first time, we unequivocally showed that Math5 and Pou4f2 are co-expressed transiently at the early stage of RGC development. This makes it formally possible that Math5 directly regulate Pou4f2, and possibly Isl1 (another early RGC gene with an identical expression pattern to Pou4f2 in RGCs) as well, to specify the RGC fate. Math5 alone is not sufficient to activate Pou4f2 and Isl1, since not all Math5-expressing cells express Pou4f2 and become RGCs. A likely scenario is that Math5 directly activates Pou4f2 and Isl1, either stochastically or through collaboration with other unknown factor(s), in a subset of Math5-expressing cells; a cell expressing Pou4f2 and Isl1 becomes committed to RGC fate; and as development progresses, Math5 expression is turned off, whereas Pou4f2 and Isl1 continue to function in advancing committed cells to differentiate into mature RGCs. Notably, downregulation of Math5 after RGC fate commitment may take place at both transcription and protein level, since levels of Math5 mRNA and its protein product abruptly diminish after newly born RGCs reach the GCL. The significance of Math5 downregulation is currently unknown, although it provides a possible mechanism by which Pou4f2-Isl1-expressing cells are irreversibly committed to an RGC fate.

Experimental Procedures

Animal care

All mice used in this study were maintained in a C57/BL×129 mixed background. In all experiments using mice, the U. S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals was followed.

Gene targeting

All gene targeting constructs were generated by recombineering following the procedure of Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2003). For Math5, a C57BL/6 BAC clone containing the Math5 gene was obtained from the BACPAC Resource Center at the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute (Oakland, CA) and was transformed into the SW102 E. coli strain (Warming et al., 2005). By gap repair, a 7.9-kb fragment of the Math5 gene was cloned into a targeting vector containing a TK cassette. To generate the Math5HA targeting vector, a mini-targeting vector containing two 50 base-pair homologous arms from sequences surrounding the final codon of Math5, sequences encoding three copies the hemagglutinin epitope YPYDVPDYA (HA-tag) from the influenza virus A, and a Neo cassette flanked by two loxP sites were constructed and used to insert the HA tag in frame into the Math5 genomic fragment by recombineering (see Fig. 1A). A BamH I site was introduced at the end of the Neo cassette for ease in genotyping (see Fig. 1A). The same strategy was used to construct the Pou4f2HA targeting vector (see Fig. 1B). An 8.0-kb Pou4f2HA genomic DNA fragment was similarly cloned from a BAC clone containing the Pou4f2 gene and sequences encoding 3 copies of HA and the Neo cassette were inserted after the final codon of Pou4f2. The oligonucleotides used in recombineering are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotides used.

| Name | Sequence | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Math5cap5 | GAG TCC TGG ACT GCG TGC CAT CAT CCT ATC CAT GGC ATC TAT CTC TCT AAT CCA CTA GTT CTA GCC TCG | Math5 genomic capture |

| Math5cap3 | GCT CAG GAT TCT TCA CTG AAG ATT ATA GAG ACA AAG CTT AAC CTC TTG ACC TCT AGA GTC GAG CAG TGT | Math5 genomic capture |

| Pou4f2cap5 | TTA GCG AGG TCC ATG CCA AAC CCC ATT GCC AGT GTC TTG CTG GTC CAT TAT CCA CTA GTT CTA GCC TCG | Pou4f2 genomic capture |

| Pou4f2cap5 | GCT CTA ATC TCA GTT GTC TGG GAA GCA ATT TCA GCA CCA TGG CCA GTA ACC TCT AGA GTC GAG CAG TGT | Pou4f2 genomic capture |

| 3xHAstop | TAC CCT TAC GAC GTT CCA GAT TAT GCA TAT CCA TAT GAT GTG CCT GAC TAT GCT TAC CCC TAC GAC GTC CCC GAT TAC GCC TAA | Coding sequence for 3xHA and a stop codon |

| Math5up | AC AAG AAG CTG TCC AAG TAC | Math5HA genotyping |

| Math5dn | CCT GTT TGA AAC GGG AA GGA | Math5HA genotyping |

| Pou4f2up | TCT GGA AGC CTA CTT CGC | Pou4f2HA genotyping |

| Pou4f2dn | CTGGGTTCACATTTACCGGA | Pou4f2HA genotyping |

The targeting constructs were linearized with Not I, electroporated into the G4 129xC57BL/6 F1 hybrid ES line (George et al., 2007) and G418 and FIAU double-resistant clones were genotyped by Southern blot hybridization (see Fig. 1C). Positive Math5HA and Pou4f2HA clones were expanded and injected into albino C57/BL6 blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. High-percentage male chimeras were then mated with albino C57/BL6 females for germline transmission. Positive pups carrying the Math5HA and Pou4f2HA alleles were identified by Southern blot hybridization and PCR. The Neo cassette was eventually removed in both lines by breeding targeted mice with CMV-Cre transgenic mice, which express Cre in the early zygote (Schwenk et al., 1995).

Genotyping

Southern hybridization with BamHI-digested genomic DNA was performed to identify targeted positive clones using external probes for both alleles. The Math5 probe detected a 21-kb band in the wild-type allele, and a 16-kb band in the Math5HA allele (see Fig. 1A, C). The Pou4f2 probe detected a 10-kb band in the wild-type allele, and a 6-kb band in the Pou4f2HA allele (see Fig. 1B, C). PCR was also used for genotyping; the primer sequences are listed in Table 1. HotStar Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen) was used and the PCR conditions for all primer pairs were as follows: pre-denaturing (95°C, 10 min); 40 cycles of denaturing (94°C, 30 sec), annealing (55°C, 30 sec), and extension (72°C, 30 sec); followed by 5 min of extra extension at 72°C.

Histology and cell counting

Embryos or adult retinas were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 7 µm. The sections were dewaxed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) as described previously (Mu et al., 2005b).

Cell counting was done as previously reported (Mu et al., 2005b; Fu et al., 2006). Total cells or Pou4f2-positive cells were counted in an arbitrarily defined length unit in the central regions of retinal sections of different genotypes. Four sections from two individual animals were counted. The significance of difference between wild-type and tagged alleles were analyzed by unpaired two-sample t test, assuming equal variances.

Immunofluorescence labeling

The immunofluorescence procedure has been described in our previous studies (Mu et al., 2005b; Fu et al., 2006). Briefly, embryos (E14.5) or eyes (E17.5 and P2) were collected and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, washed three times with PBST (PBS pH7.4, plus 0.2% Tween 20), embedded in OCT, and frozen. Sixteen-micron cryosections were collected, washed 3 × 10 min with PBST, and blocked with 2% BSA in PBST for one hour. The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies with appropriate dilution in 2% BSA-PBST for one hour, followed by 3 × 10 min PBST washing. This was then followed by staining with fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibody and PBST washes. In some cases the nuclei were stained with propidium iodide. The slides were then mounted with AquaMount (Lerner Laboratories) and examined under a confocal microscope. Antibodies used: anti-Pou4f2 (Santa Cruz, 1:150), anti-HA (Santa Cruz, 1:100), anti-p75 (Promega, 1:200), anti-NF160 (Sigma, 1:200).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jan Parker-Thornburg and her staff at the Genetically Modified Mouse Facility (GEMF), M. D. Anderson Cancer Center for assistance in generating the knock-in mouse alleles. This study was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute (EY011930 and EY010608) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (G-0010) to W.H.K., and the E. Matilda Ziegler Foundation for the Blind to X.M. Research in X.M.’s laboratory is supported in part by a departmental Unrestricted Grant Award from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology at SUNY Buffalo. The GEMF is supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grant CA016672.

References

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Kanekar S, Vetter ML, Tucker PK, Gemza DL, Glaser T. Math5 encodes a murine basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor expressed during early stages of retinal neurogenesis. Development. 1998;125:4821–4833. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Patel S, Brzezinski J, Glaser T. Math5 is required for retinal ganglion cell and optic nerve formation. Development. 2001;128:2497–2508. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.13.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkman L, McEvilly RJ, Luo L, Ryan AK, Hooshmand F, O'Connell SM, Keithley EM, Rapaport DH, Ryan AF, Rosenfeld MG. Role of transcription factors Brn-3.1 and Brn-3.2 in auditory and visual system development. Nature. 1996;381:603–606. doi: 10.1038/381603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Sun H, Klein WH, Mu X. Beta-catenin is essential for lamination but not neurogenesis in mouse retinal development. Dev Biol. 2006;299:424–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L, Wang SW, Huang Z, Klein WH. POU domain factor Brn-3b is essential for retinal ganglion cell differentiation and survival but not for initial cell fate specification. Dev Biol. 1999;210:469–480. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L, Xiang M, Zhou L, Wagner DS, Klein WH, Nathans J. POU domain factor Brn-3b is required for the development of a large set of retinal ganglion cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3920–3925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick D, Sutherland H, Robertson G, Whitelaw E. Variegated expression of a globin transgene correlates with chromatin accessibility but not methylation status. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4902–4909. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SH, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten K, Korets-Smith E, Murphy J, Stevens ME, Haigh JJ, Nagy A. Developmental and adult phenotyping directly from mutant embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4455–4460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609277104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DS, Mortazavi A, Myers RM, Wold B. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science. 2007;316:1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1141319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimple ME, Sondek J. Affinity tag for protein purification and detection based on the disulfide-linked complex of InaD and NorpA. Biotechniques. 2002;33:578, 580, 584–578. doi: 10.2144/02333rr01. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 2003;13:476–484. doi: 10.1101/gr.749203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:109–118. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Beremand PD, Zhao S, Pershad R, Sun H, Scarpa A, Liang S, Thomas TL, Klein WH. Discrete gene sets depend on POU domain transcription factor Brn3b/Brn-3.2/POU4f2 for their expression in the mouse embryonic retina. Development. 2004;131:1197–1210. doi: 10.1242/dev.01010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Fu X, Beremand PD, Thomas TL, Klein WH. Gene regulation logic in retinal ganglion cell development: Isl1 defines a critical branch distinct from but overlapping with Pou4f2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6942–6947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802627105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Fu X, Sun H, Beremand PD, Thomas TL, Klein WH. A gene network downstream of transcription factor Math5 regulates retinal progenitor cell competence and ganglion cell fate. Dev Biol. 2005a;280:467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Fu X, Sun H, Liang S, Maeda H, Frishman LJ, Klein WH. Ganglion cells are required for normal progenitor- cell proliferation but not cell-fate determination or patterning in the developing mouse retina. Curr Biol. 2005b;15:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Klein WH. A gene regulatory hierarchy for retinal ganglion cell specification and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, Garrick D, Wu W, Kearns M, Martin D, Whitelaw E. Position-dependent variegation of globin transgene expression in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5371–5375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, Hirst M, Bainbridge M, Bilenky M, Zhao Y, Zeng T, Euskirchen G, Bernier B, Varhol R, Delaney A, Thiessen N, Griffith OL, He A, Marra M, Snyder M, Jones S. Genome-wide profiles of STAT1 DNA association using chromatin immunoprecipitation and massively parallel sequencing. Nat Methods. 2007;4:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5080–5081. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld M, Patrick JD, Soreq H. Position effect variegations and brain-specific silencing in transgenic mice overexpressing human acetylcholinesterase variants. J Physiol Paris. 1998;92:249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(98)80028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpe K. Overview of tag protein fusions: from molecular and biochemical fundamentals to commercial systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;60:523–533. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokes SA, Ji H, Wong WH, McMahon AP. A genome-scale analysis of the cis-regulatory circuitry underlying sonic hedgehog-mediated patterning of the mammalian limb. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2651–2663. doi: 10.1101/gad.1693008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SW, Gan L, Martin SE, Klein WH. Abnormal polarization and axon outgrowth in retinal ganglion cells lacking the POU-domain transcription factor Brn-3b. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:141–156. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SW, Kim BS, Ding K, Wang H, Sun D, Johnson RL, Klein WH, Gan L. Requirement for math5 in the development of retinal ganglion cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15:24–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.855301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SW, Mu X, Bowers WJ, Kim DS, Plas DJ, Crair MC, Federoff HJ, Gan L, Klein WH. Brn3b/Brn3c double knockout mice reveal an unsuspected role for Brn3c in retinal ganglion cell axon outgrowth. Development. 2002;129:467–477. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang M, Zhou L, Macke JP, Yoshioka T, Hendry SH, Eddy RL, Shows TB, Nathans J. The Brn-3 family of POU-domain factors: primary structure, binding specificity, and expression in subsets of retinal ganglion cells and somatosensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4762–4785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04762.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Ding K, Pan L, Deng M, Gan L. Math5 determines the competence state of retinal ganglion cell progenitors. Dev Biol. 2003;264:240–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]