Abstract

Large cell calcifying sertoli cell tumor (LCCSCT) is an exceptionally rare neoplasm originating from sperm cord cells. The tumors have relatively low malignant potential and unlikely proceed to metastasis formation. The lesions may occur in an isolated form or in ca. 40% of cases may be associated with genetic abnormalities, by and large Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and Carney complex. At presentation, 20% of LCCSCT cases are bilateral and/or multifocal. Owning to characteristic skin lesions and particular hyperechoic ultrasound image of the tumor, preliminary diagnosis of the syndromic LCCSCT is possible in the preoperative period. Consequently, testicle organ–sparing procedure can be attempted, which is especially justified in bilateral lesions. Here, we report a case of a bilateral LCCSCT in a 20-year-old man with atypical Peutz–Jeghers syndrome due to amplification of the exon 1 of STK11 gene who was successfully treated with bilateral testicle-sparing tumorectomies.

Keywords: Large cell calcifying sertoli cell tumor, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, Organ-sparing testicular surgery, STK11 amplification

Introduction

Due to its generally malignant behavior, radical inguinal orchidectomy is the “gold standard” for the treatment of a testicular tumor. Nevertheless, in some less frequent histological subtypes of tumors with low malignant potential organ-sparing approach: partial orchidectomy or even testicle-sparing excisions of tumors could be attempted [1]. Since there are no reliable non-invasive diagnostic tests available which would allow unequivocal differential diagnosis of the lesion in the preoperative period, it is recommended that the testicle should be first exposed and frozen section biopsy should be performed prior to main surgery [2].

Large cell calcifying sertoli cell tumor (LCCSCT) is a very uncommon sex cord stromal neoplasm. Usually, the disease presents in adolescents and young adults with slowly enlarging painless testicular mass or gynecomastia [3]. In up to 40% of cases, it coincidences with inherited genetic syndromes such as Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS, MIM#175200) or Carney complex (MIM#160980) [4]. These autosomal dominant multiple neoplasia syndromes present with a variety of pigmented lesions of the skin and mucosae and a number of tumors affecting many organs. Yet still, only a small fraction of syndromic patients develop LCCSCT—in total, about 30 cases of testicular lesions have been previously reported in the English language literature in this subgroup of patients (reviewed by Ulbright et al. [3]). The tumors possess low malignant potential and rarely give distant metastases. Therefore, instead of standard radical orchidectomy, in case of LCCSCT suspicion partial orchidectomy is recommended.

Here, we report a case of bilateral LCCSCT in a 20-year-old man with skin lesions suggestive for PJS, which was successfully treated with bilateral testicle-sparing tumorectomies.

Case description

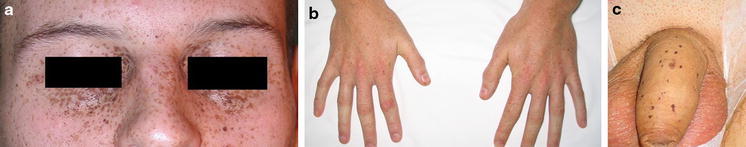

A 20-year-old man was referred to the urological department due to bilateral testicular enlargement. On physical examination, two hard, non-tender tumors were detected. Besides, patient presented with dispersed lentiginosis on the face, hands, penis and on the buccal mucosa (Fig. 1). Testicular lesions were noticed 2 months before. Ultrasound examination revealed two hyperechoic 10–11 × 9 mm tumors. Serum alpha-fetoprotein, beta-hCGH and testosterone levels were within normal range. Abdomen and chest CT showed no evidence of metastases or other pathologies.

Fig. 1.

Characteristic skin lesions—lentigosis on the face (a), hands (b) and penis (c)

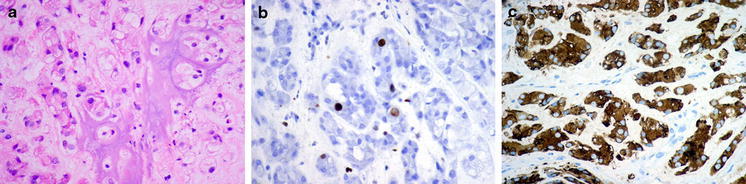

Peculiar skin lesions and hyperechoic ultrasound image of the bilateral tumors suggested underlying constitutional genetic abnormality and hence plausibly benign character of the testicular lesions. Consequently, right tumorectomy was attempted. Frozen section intraoperative consultation was indicative of benign testicular neoplasm, confirming organ-sparing approach. Accordingly, left side surgery was performed in the similar manner. The final histopathological diagnosis was LCCSCT (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Microscopic features of the tumor a Testicular tumor composed of trabecles, small tubules and cords of polygonal mildly pleomorphic cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm embedded in myxoid stroma with scattered granulocytes. Additionally, prominent area of ossification is visible. b Low (2%) proliferative index of tumor cells with Ki-67 antibody. c Strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity of alpha inhibin in tumor cells (shown). The tumor had also strong immunoreactivity for S-100 protein

In order to verify clinical suspicion of the Peutz-Jaghers syndrome, genetic testing was performed. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes in accordance with the standard phenol-chlorophorm protocol. Mutational screening of the STK11 gene was performed by direct sequencing of all exons and adjacent intronic junctions of the gene. Large genomic rearrangements were analyzed by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification method using SALSA MLPA P101-A2 STK11 kit (MCR Holland), as previously described [5]. STK11 gene amplification confined to the promoter region and exon 1 was detected; however, due to large size of the gene fragment in question and its high GC content, the exact breaking points of the rearrangement were not established. Nevertheless, since amplification of the exon 1 results in frameshift and hence premature termination of translation, we may safely conclude that it is a disease-causing mutation. The resulting aberrant mRNA either will be subjected to nonsense-mediated decay or encode a truncated, malfunctioning protein comprising of mere 96 N-terminal amino acids instead of 433 residues present in the wild-type STK11 protein.

Skin lesions, histopathology type of the testicular tumors and results of genetic tests all confirmed diagnosis of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. The patient was referred to genetic department for further management. No colonic polyps were found on colonoscopy. Follow-up at 6 months showed no sign of tumor recurrence. Testosterone level remained normal as well as sperm parameters.

Discussion

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is a rare genetic disorder characterized by multiple gastrointestinal (GI) hamartomatous polyps, mucocutaneous pigmentation and increased predisposition to various neoplasms [6]. Typically, PJS diagnosis is made in young adults presenting with gastrointestinal problems such as obstruction, pain or bleeding caused by the presence of hamartomatous polyps in the digestive tract, who in addition to abdominal symptoms have peculiar melanin hyperpigmented spots on the face, especially around lips and nostrils, oral mucosa, genitals, anus and sometimes on hands or feet. Even though 88% of PJS patients have GI polyps [6], the reported patient neither had ever manifested any symptoms of gastrointestinal disease, nor had polyps detected during eventual GI work-up. Yet still, since the most common site of PJS polyps is the small intestine that is a difficult organ to examine by clinical or radiological means, it cannot be excluded that in the future the patient becomes symptomatic. The second atypical feature of the presented case is the type of causative mutation. Even though one-third of PJS patients is found to have rearrangements of the STK11 gene, on the whole these are large exonic deletions [5]. In accordance with Human Gene Mutation Database (http://www.hgmd.org/ accessed Oct. 2011), our patient is the second case worldwide with an exonic amplification affecting STK11 gene, the other patient having exon 7 duplication. In view of the rarity of such mutation, no definite conclusions with respect to genotype–phenotype correlations can be drawn.

In addition to polyps and melanin spots that are the two constant features of the syndrome, PJS patients have increased risk of developing various tumors. The relative risk of cancer in these individuals is 15 times the general population risk and the cumulative cancer risk is 76–81% by the age of 70 years [6, 7]. The most common sites are small intestine, colon, pancreas, stomach, lung, breast, uterus, and ovary. The occurrence of ovarian tumors far exceeds that of testicular tumors in this disorder, with the estimated cumulative risk of 6–21% in PJS women [6, 7]. Conversely, LCCSCTs have been observed in a few PJS patients only, nevertheless accounting for up to one-third of all LCCSCT reported in the available literature [3, 4].

In contrast to sporadic LCCSCT cases, PJS men develop cancer at earlier age (6.5 vs. 16 years) [3, 4]. In PJS, the first manifestation typically results from hormonal activity of the tumor and can be observed clinically as bilateral gynecomastia and precocious puberty, while sporadic cases usually present with non-tender testicular mass in adolescence. In general, PJS tumors are bilateral and may be multifocal, while only 20% of sporadic cases affect both testicles [3, 4].

By and large LCCSC tumors are benign, especially if they are small and bilateral. Malignant behavior can be observed in 17% of cases, mainly in lesions >4 cm or in patients over the age of 20 [4]. Preoperative work-up should include evaluation of retroperitoneal lymph nodes, bones, liver and lungs as these are the most common sites of cancer metastases. On ultrasound imaging LCCSCT are usually round, regular, and hyperechoic with acoustic shadow. Doppler ultrasound shows increased blood flow in the adjacent area. Distinctive ultrasound picture helps making preliminary diagnosis, but it must be remembered that intratumor hyperechoic elements may also be present in seminomas, carcinomas embrionale, mature teratomas as well as in benign lesions caused by post-traumatic or post-infectious inflammation.

In comparison with traditional treatment of testicular tumors by means of radical inguinal orchidectomy, in case of LCCSCT partial orchidectomy/tumorectomy seems to be more beneficial surgical approach [1]. Nevertheless, testicle-sparing surgery is rational only if several conditions are fulfilled. To start with, benign character of the tumor must be confirmed by intraoperative frozen section analysis. Secondly, the tumor has to be located far from the rete testis and be smaller than 20–25 mm in order to have enough viable testicular tissue left. Finally, preoperative testicular function has to be normal as documented by testosterone level [2]. More to the point, after this kind of surgery, close follow-up must be implemented and it is usually done by testicular ultrasound imaging [1].

In cases of LCCSCTs that present with additional abnormalities suggestive of genetic syndromes such as heart myxoma in Carney complex, or melanin spots and/or hamartomatous polyps in PJS detection of the testicular tumor may help to diagnose these entities and hence enable starting their adequate treatment and further lifelong oncological surveillance. The reported patient is a case in point. He does not meet the generally acknowledged clinical criteria for PJS diagnosis [7] since he had no signs of GI disease, or positive family history of PJS in a close relative(s). Also clinical manifestation of LCCSCT was atypical, with no endocrinological disturbances and relatively late age at onset. Nevertheless, STK1 mutational screening allowed for molecular confirmation of the disease pointing out the importance of molecular testing in LCCSCT patients.

Conclusions

Due to a low malignant potential of LCCSCT, it may be very efficiently treated by testicle-sparing method, especially in cases of bilateral tumor. Characteristic phenotypic features of the patients with genetic dysplastic syndromes that may coincide with LCCSCT and typical appearance of the tumor on ultrasound facilitate its diagnosing prior to surgery and hence reduce the invasiveness of the treatment. Conversely, LCCSCT diagnosis enables identification of the underlying genetic syndrome that may predispose to increased risk of other neoplasia.

Acknowledgments

This work has been financed by Polish Ministry of Science and Education grant No N402 481537.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Giannarini G, Dieckmann KP, Albers P, Heidenreich A, Pizzocaro G. Organ-sparing surgery for adult testicular tumours: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2010;57:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner H, Höltl L, Maneschg C, Berger AP, Rogatsch H, Bartsch G, Hobisch A. Frozen section analysis-guided organ-sparing approach in testicular tumors: technique, feasibility and long-term results. Urology. 2003;62:508–513. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00465-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulbright TM, Amin MB, Young RH. Intratubular large cell hyalinizing sertoli cell neoplasia of the testis: a report of 8 cases of a distinctive lesion of the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:827–835. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180309e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halat SK, Ponsky LE, MacLennan GT. Large cell calcifying sertoli cell tumor of testis. J Urol. 2007;177:2338. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aretz S, Stienen D, Uhlhaas S, Loff S, Back W, Pagenstecher C, McLeod DR, Graham GE, Mangold E, Santer R, Propping P, Friedl W. High proportion of large genomic STK11 deletions in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:513–519. doi: 10.1002/humu.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giardiello FG, Trimbath JD. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Lier MG, Westerman AM, Wagner A, Looman CW, Wilson JH, de Rooij FW, Lemmens VE, Kuipers EJ, Mathus-Vliegen EM, van Leerdam ME. High cancer risk and increased mortality in patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Gut. 2011;60:141–147. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]