Abstract

The extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase, ERK2, fully activated by phosphorylation and without a His6-tag, shows little tendency to dimerize with or without either calcium or magnesium ions when analyzed by light scattering or analytical ultracentrifugation. Light scattering shows that ~ 90% of ERK2 is monomeric. Sedimentation equilibrium data (obtained at 4.8–11.2 μM ERK2) with or without magnesium (10 mM) are well described by an ideal one-component model with a fitted molar mass of 40,180 ± 240 Da (- Mg2+ ions) and 41,290 ± 330 Da (+ Mg2+ ions). These values, close to the sequence-derived mass of 41,711 Da, indicate that no significant dimerization of ERK2 occurs in solution. Analysis of sedimentation velocity data for a 15 μM solution of ERK2 with an enhanced van Holde-Weischet method determined the sedimentation coefficient (s) to be ~ 3.22 S for activated ERK2 with or without 10 mM MgCl2. The frictional coefficient ratio (f/f0) of 1.28 calculated from the sedimentation velocity and equilibrium data is close to that expected for a globular protein of ~ 42 kDa. The translational diffusion coefficient of ~ 8.3 × 10-7 cm2s-1 calculated from the experimentally determined molar mass and sedimentation coefficient agrees with the value determined by dynamic light scattering in the absence and presence of calcium or magnesium ions and a value determined by NMR spectrometry. ERK2 has been proposed to homodimerize and bind only to cytoplasmic but not nuclear proteins. Our light scattering data show, however, that ERK2 forms a strong 1:1 complex of ~ 57 kDa with the cytoplasmic scaffold protein PEA-15. Thus ERK2 binds PEA-15 as a monomer. Our data provide strong evidence that ERK2 is monomeric under physiological conditions. Analysis of the same ERK2 construct with the non-physiological His6-Tag shows substantial dimerization under the same ionic conditions.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), are pivotal enzymes in cellular communication and include the extracellular signal-regulated kinase family (ERKs), the c-Jun N-terminal kinase family (JNKs), and the p38MAP kinase family (1). The ERKs mediate effects on proliferation and differentiation by growth factors and hormones. The JNKs and p38 MAPKs help fashion cellular responses to stress. Breakdown in the control of these enzymes can lead to numerous cancers and degenerative diseases (2). MAPKs each have multiple protein substrates, yet paradoxically elicit specific biological responses. An understanding of the rules governing the interactions between these kinases and other cellular proteins will provide insight into how this specificity is achieved, and help identify strategies to correct biological signals when they go awry.

The ERK1/2 pathway begins with Ras, a GTPase (3). Ras is anchored to the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane and is activated by a cascade of events after various hormones bind to their respective cell surface receptors. Following activation, Ras recruits Ser/Thr-specific Raf kinases to the cellular membrane (4) and induces their activation through a series of complex phosphorylation events (5, 6). Phosphorylated Raf kinases then activate two closely related cytoplasmic kinases, MKK1 and MKK2, by phosphorylating each within its respective activation loop at Ser-217 and Ser-221 (7). Activated MKK1 and MKK2 can then activate ERK1 and ERK2 by phosphorylation (8). Activated ERK1/2 is found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, but only cytoplasmic ERK1/2 is likely to activate the Ser/Thr-specific RSK1/2 kinases (9-12), which can then join nuclear ERK1/2 to phosphorylate transcriptional regulators that include Elk-1 (13), SAP1 and SAP2 (14). This transcriptional activation results in the rapid appearance of products of immediate early genes, which include transcription factors that control cell survival and/or the cell cycle.

X-ray crystallographic analysis of activated His6-ERK2 revealed a putative dimeric interface facilitated by a non-helical leucine zipper comprised of residues L333, L334, and L336 from each monomer subunit (15). Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated His6-ERK2 were reported to self-associate to form homodimers with dissociation constants of 7.5 and 20,000 nM, respectively, in the absence of added divalent metal ions (15). His6-ERK2 has been reported to be monomeric in the presence of chelating agents, such as EDTA and EGTA (16, 17) and divalent metal ions such as Mg2+ and Ca2+ have been reported to be essential for dimerization (16). Studies in vivo failed to detect the presence of GFP-ERK2 homodimers in cells under conditions where GFP-ERK•GFP-MKK1 dimers were readily observed (18). However, ERK2 was reported to associate as a homodimer to cytoplasmic scaffolds following cell stimulation and it was proposed that this ‘assembly-mediated’ dimerization in the cytoplasm is important for tumorigenesis (19). In contrast, ERK2 was reported to associate with nuclear proteins only as a monomer (19).

His6-tags have been shown to promote the self-association of some proteins (20, 21) and could potentially influence the tendency of ERK2 monomers to dimerize. For example, we have found that the presence of a His6-tag at the N-terminus of p38 MAPK alpha dramatically increases its ability to be phosphorylated by MKK6 (22). Furthermore, transition metals such as nickel and cobalt bind His6-tags (23) and if present in trace amounts could influence the properties of a protein. We reevaluated the self-association of activated ERK2 without the His6-tag and also asked whether ERK2 self-associates on the cytoplasmic scaffold protein, PEA-15. We find that activated ERK2 binds to PEA-15 as a monomer. These results suggest that activated ERK2 is predominantly monomeric.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Materials

Yeast extract, tryptone and agar were purchased from US Biological (Swampscott, MA). Competent cells used for amplification and expression were obtained from Novagen (Gibbstown, NJ). Ni-NTA Agarose, QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit, QIAquick PCR Purification Kit and QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit were provided by Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Enzymes for restriction digestion and ligation were obtained from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA) and Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA) respectively. All the buffer components used for protein purification and experimental procedures were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Amersham Biosciences (Pittsburgh, PA) provided the FPLC system and the columns for purification. P81 cellulose papers were obtained from Whatman (Piscataway, NJ). ATP was purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Radiolabelled [γ-32P]-ATP was obtained from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA).

Protein Preparation

Construction of a His6-cleavable construct of ERK2 in pET28a

We previously constructed pET28-His6-ERK2 cysless-PKA. A mutant of ERK2 lacking cysteines with a thrombin cleavable N-terminal His6-tag and C-terminal PKA tag cloned into a pET28a expression vector at the NdeI and HindIII restriction sites (24). To generate a wild type construct a SacII–HindIII fragment containing all the mutations and the C-terminal PKA tag was replaced by DNA encoding for wild type ERK2 (Rattus norvegicus mitogen activated protein kinase 1, GenBank accession number NM_053842) (24). The resulting construct contains a His6-tag followed by a thrombin cleavage site (Met-Gly-Ser-Ser-His-His-His-His-His-His-Ser-Ser-Gly-Leu-Val-Pro-Arg-Gly-Ser-His) at the N-terminus of the ERK2 sequence immediately preceding Met-1. The sequence was verified at the Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology (ICMB) Sequencing Facility at the University of Texas at Austin.

ERK2 expression and purification

A pET28a-His6-ERK2 plasmid with a cleavable His6-tag was transformed into BL21 (DE3) cells. Cells from a single colony were used to inoculate 100 mL of LB medium containing 30 μg/mL kanamycin and grown overnight at 37° C. The culture was diluted 100-fold into 4 liters of LB broth containing 30 μg/mL kanamycin and was grown at 37 °C to an optical density of 0.6 at 600 nm. The cells were induced with 500 μM IPTG and cultured for an additional 4 hours at 30 °C. The cells were harvested, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until lysis. Cells were lysed in 200 mL of buffer A [40 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 0.03% Brij-30, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.1 mM TPCK and 0.1 mM PMSF] containing 750 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole and 1% Triton X-100 and sonicated at 4 °C for 20 minutes using a 5 second pulse with 5 second intervals. The lysate was centrifuged (16,000 rpm) at 4 °C for 30 minutes and the supernatant was agitated gently with 10 mL Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen) at 4 °C for 1 hour. The beads were washed with 200 mL of buffer A containing 10 mM imidazole with pH re-adjusted to 7.5 then eluted with 50 mL of buffer A containing 200 mM imidazole with pH re-adjusted to 8.0. An aliquot of the eluted protein, 50 mL, was loaded onto a Mono-Q HR 10/10 anion exchange column pre-equilibrated with buffer B [20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.03% Brij-30, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol]. The protein was chromatographed in Mono-Q buffer with a gradient of 0-0.5 M NaCl over 17 column volumes (~170 mL) and was eluted at ~ 0.25 M NaCl. The eluted fractions of His6-ERK2 were pooled and dialyzed overnight against either buffer S [25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT and 10% glycerol] for further activation or thrombin cleavage buffer C [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol] for further His6-tag cleavage. Cleavage was performed at 23 °C for 5 hours by mixing 1 unit of thrombin (Novagen) per mg ERK2. The cleavage was verified by electrophoresis in 10% SDS-PAGE. After His6-tag cleavage, the protein was dialyzed overnight against buffer B, then filtered and loaded on a Mono-Q HR 10/10 anion exchange column. The separation of tagless ERK2 from uncleaved protein or His6-tag was accomplished as described above. Cleavage was confirmed by ESI-MS. Eluted fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer S for further activation.

Activation of ERK2

Either His6-cleaved or His6-tagged ERK2 (7 μM) was incubated with constitutively active MKK1 (0.35 μM) in buffer D [25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EGTA, 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP] to a 50 mL final volume at 27 °C for 6 hours. The activated protein was dialyzed against Mono-Q buffer B (pH 8) and purified by Mono-Q HR 10/10 anion exchange column as described above. The purity and identity of the active ERK2 was verified by running the protein fractions on 10% SDS-PAGE and by ESI-MS. Eluted fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer S then concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 (10,000 MWCO), frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. For Analytical Ultracentrifugation, the active tagless enzyme was further purified by HIC, diluted 10 fold in buffer E [50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 M ammonium sulfate] and loaded onto HiLoad™ 16/10 Phenyl Sepharose™ High Performance column (2.6 × 10 cm) that was preequilibrated with buffer E. The column was run with a decreasing gradient concentration of ammonium sulfate from 1 to 0 M. The protein was eluted at about 0.2 M ammonium sulfate. Eluted fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer S. The purity of the protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. In all the cases, the concentration of activated ERK2 was determined with an extinction coefficient (A280) of 52,067 cm-1 M-1 (24). The activation status of the protein was verified by ESI-MS performed at the Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology Mass Spectrometry Facility at the University of Texas at Austin and also by an in vitro kinase assay with Ets as a substrate (25).

Constitutively active MKK1 and Ets expression and purification

Expression and purification of MKK1 and Ets have been described previously (25).

Expression and Purification of tagless full length PEA-15

Full length PEA-15 was cloned into the pET28a vector (26) and transformed into BL21 (DE3)-pLys cells. Cells were grown at 37 °C in Luria broth medium containing 30 μg/mL kanamycin to an optical density of 0.6 at 600 nm. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and cultured for an additional 4 h at 30 °C before harvesting. The purification of His6-PEA-15 was similar to that for ERK2, except a 0—250 mM NaCl gradient was used for elution of PEA-15 from the Mono-Q HR 10/10 column (The yield was ~ 65 mg/L of culture). His6-PEA-15 (10 mg) was cleaved to tagless PEA-15 by thrombin in a 10 mL reaction volume containing 10 units of thrombin (Calbiochem). The cleavage was carried out for 5 h at 25 °C in buffer C. The resulting PEA-15 contains three residues Gly-Ser-His at the N-terminus before Met-1. The reaction sample (10 mL) was then dialyzed against buffer B at 4 °C and applied to a Mono Q HR 10/10 anion exchange column. The eluted fractions were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration to ~1 mM. A 2 mL aliquot of the concentrate was applied to a Superdex™ 75 gel filtration column equilibrated in buffer F (25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT). The collected fractions were combined and dialyzed against buffer S. Cleavage of the His6-Tag and final purity were confirmed by SDS-PAGE. The concentration was determined with an extinction coefficient (A280) of 10930 cm-1 M-1 for PEA-15 (27).

Assay

in vitro assays for tagless active ERK2 were performed in 100 μL volumes at 30 °C in buffer G [25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2 and 40 μg/mL BSA] containing 2 nM ERK2, 500 μM radiolabelled [γ-32P]-ATP (specific activity = 1×1015 c.p.m./mol) and 0-400 μM Ets. Reaction mixtures containing everything except ATP were prepared and kept on ice until the time of assay. The reaction mixture was incubated for 10 minutes at 30 °C before initiating the reaction with the radiolabelled ATP. Aliquots (10 μL) were spotted onto P81 filter papers at fixed times. The filter papers were each washed three times for 15 minutes with 50 mM phosphoric acid to remove excess ATP and washed once with acetone for drying. The amount of phosphate incorporated into Ets was determined by the associated counts/min on a scintillation counter (Packard 1500) at a σ value of 2.

Light Scattering

Active ERK2 (100-300 μM) was dialyzed against buffer F with or without MgCl2/CaCl2 (0.5 or 10 mM) prior to the light-scattering experiments. PEA-15 (1000 μM) was also dialyzed against the same buffer without MgCl2/CaCl2 prior to use. Light-scattering analysis was performed on 100-300 μM active tagless ERK2 and 200 μM active His6-tagged ERK2 in different experiments. The analysis of ERK2/PEA-15 association was made by injecting 20 μL of 300 μM active tagless ERK2 alone, 20 μL of 1 mM PEA-15 alone, and then 20 μL each of active tagless ERK2/PEA15 mixtures (1:1 and 1:2 molar ratios) where ERK2 concentration was fixed at 300 μM to the size-exclusion column. Static light-scattering measurements were made as previously described (16, 17) with the addition of dynamic light scattering with the Wyatt QELS detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA). All measurements were made at 25 °C. Size-exclusion chromatography was performed as previously described (16, 17) with a TSK-GEL G3000PWXL column (300 × 7.8 mm ID, 14 mL column volume, Tosoh Bioscience LLC). Buffer F, freshly prepared with Nanopure water (~18.3 MΩ cm) and filtered through a 0.02 μm filter (Anodisc 47, Whatman, catalog # 6809-5002) was used to establish the light-scattering and refractive index baselines. Bovine serum albumin monomer (Sigma A1900) was injected to the column at 2 mg/mL for normalization of the light-scattering detectors. The size-exclusion chromatography was carried out at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min at room temperature with a run time of ~ 40 min. Samples were centrifuged for ~ 30 sec to remove any insoluble components prior to injection. Molar masses, peak concentrations and hydrodynamic radii were determined with Astra software (Wyatt Technology).

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Both sedimentation velocity and equilibrium experiments were carried out at 20 °C in a Beckman-Coulter Optima XL-I/A analytical ultracentrifuge with an AN60Ti rotor. The buffer used for all experiments contained 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM TCEP, with or without 10 mM MgCl2 and various concentrations of tagless activated ERK2 as described below. Buffer densities were measured with an Anton Paar DMA 5000 density meter and found to be 1.0064 and 1.0057 g/cm3 with and without 10 mM MgCl2 respectively. Buffer viscosities calculated with the software SEDNTERP (28) were 1.023 and 1.019 cPoise with and without MgCl2 respectively. A partial specific volume () of ERK2 of 0.7403 cm3/g at 20 °C was calculated from the amino acid sequence with SEDNTERP.

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were carried out with loading concentrations of 4.8, 8.0, and 11.2 μM tagless active ERK2 in six-sector epon-charcoal centerpieces with quartz windows. Samples (110 μL) were spun at rotor speeds of 15,000 and 25,000 rpm until equilibrium. Data were collected at 280 nm with 10 replicates with a step size of 0.001 cm. Data sets consisting of 6 curves were globally fitted to various models using UltraScan version 9.9 software (29). Sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out in double sector epon-charcoal centerpieces with quartz windows. The assembled cell was loaded with 430 μL of 15.2 μM tagless active ERK2 sample without MgCl2 and allowed to equilibrate thermally with the rotor in the centrifuge chamber for a few hours. Scans were collected at 45,000 rpm in continuous mode at 280 nm with 0.002 cm radial resolution and zero time intervals. Following this, 1.55 μL of MgCl2 from a 2.8 M stock solution was added to the ERK2 sample in the assembled cell to give a final MgCl2 concentration of 10 mM and tagless active ERK2 of 15 μM. The cell was agitated to re-distribute the sedimented protein and the sample run again. Data were analyzed by the enhanced van Holde-Weischet method (30) as incorporated in Ultrascan version 9.9. All sedimentation coefficient values are reported for water at 20 °C.

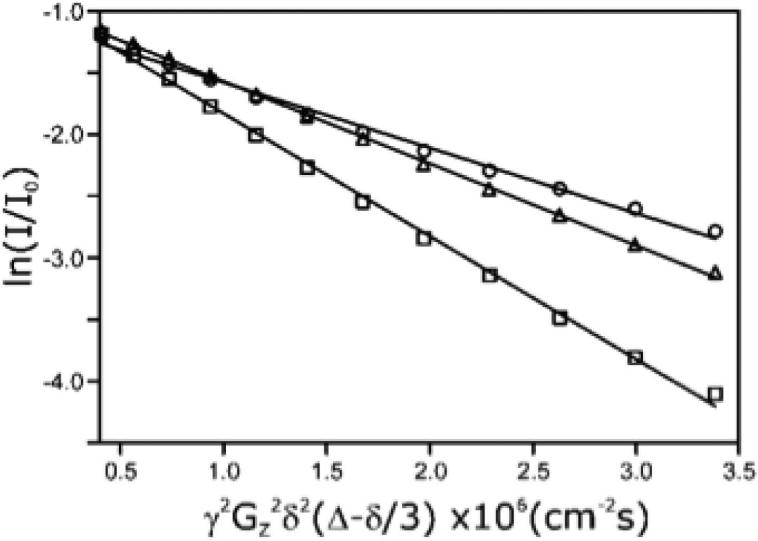

1H NMR

1H NMR experiments used a Bruker Avance spectrometer (operating at a nominal frequency of 600MHz) at 298K. NMR self diffusion experiments were performed on tagless activated ERK2 in the absence or presence of 10 mM MgCl2 in a buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 2 mM DTT. Lysozyme (1 mM in 30 mM NaCl, pH 2.8) was used for calibration, and bovine serum albumin (0.65 mM in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.8) was used as a standard. Diffusion coefficients were measured using a standard spin-echo and LED (longitude encode-decode) with bipolar encoding gradients (31), two z-spoil gradients and Watergate water suppression. 16 1H spectra were acquired with 1024 scans, increasing gradient strength from 3.8 to 34.3 G/cm, and were repeated three times. The encoding gradients were set to 4 ms and the diffusion delay was 50 ms. The self-diffusion coefficient (Ds) is obtained from a fit of the signal decay to the relationship I/Io = exp[-γ2G2δ2(Δ-δ/3)/Ds], where γ = the 1H gyromagnetic ratio, δ = the Gradient duration (s), G = gradient strength (G/cm), Δ = time between PFG (pulse field gradient) pulse (s), and I = the echo amplitude. Data were analyzed using Bruker Topspin 1.3 software.

RESULTS

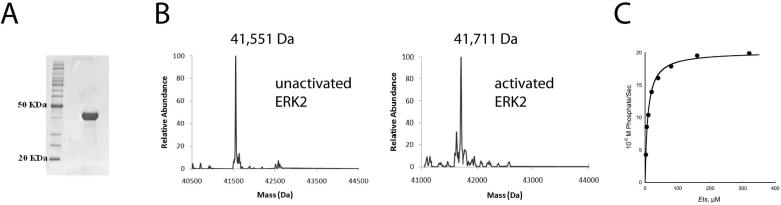

Biophysical studies of the self-association of ERK2 have historically utilized a polypeptide containing six histidines inserted immediately between the initiating methionine and the first coding residue, Ala-2 (32). However, hexahistidine tags can promote self-association of some proteins (20, 21) so we constructed a new DNA expression plasmid encoding ERK2 to avoid this problem. The construct was designed such that cleavage by thrombin produces an ERK2 protein with just three residues Gly-Ser-His at the N-terminus before Met-1. Previously, we prepared activated His6-ERK2 by utilizing a constitutive form of the upstream activator MKK1 (25). We used a mass spectrometry-based analysis of the undigested or tryptically digested protein to establish that MKK1 exclusively phosphorylates His6-ERK2 on Thr-183 and Tyr-185 within the activation loop. Thrombin-cleaved ERK2 was prepared and activated as described above (Fig. 1A and B) (See Materials and Methods). Mass spectrometry established that cleavage had occurred exclusively at the thrombin site and that the activated ERK2 contains two phosphates (Fig. 1B). The tagless ERK2 was found to exhibit the same kinetic properties as His6-ERK2. Initial velocity data at different concentrations of Ets were fitted with the Michaelis-Menten parameters: kcat = 19 s-1 and Km = 8.5 μM (Fig. 1C) which matches what was established before for His6-ERK2 by Waas et al. (33).

Figure 1. Purification of tagless ERK2.

A. Fractionation of tagless activated ERK2 by 10% SDS/PAGE. A BenchMark™ Protein Ladder (Invitrogen) is shown as a reference. B. Mass spectrometry of thrombin-cleaved ERK2. (left, inactive form; right, fully active form). A constitutively active form of MKK1 was used to activate ERK2 by phosphorylation of two residues. C. Phosphorylation of the substrate Ets by activated tagless ERK2 in the presence of 0.5 mM ATP and 10 mM MgCl2.

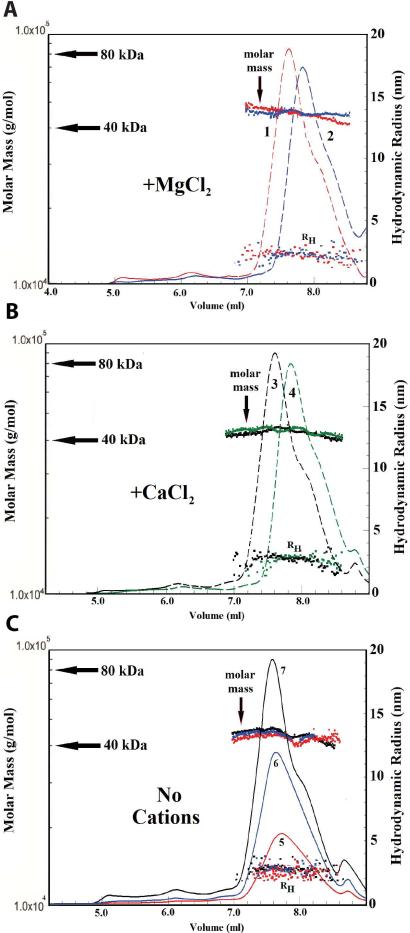

Measurement of the ability of tagless activated ERK2 to self-associate to a homodimer was made by gel filtration followed by light scattering (See Materials and Methods). The following buffer conditions were employed: 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0, 0.5 or 10 mM MgCl2/CaCl2, at 25 °C. The molar mass distribution, as a function of elution volume, is shown for each sample in Fig. 2A, 2B, & 2C. The concentrations of each of the central major peaks for the (~7.2 to 8.8 mL) (determined at the peak maximum) were in the range of 0.4 mg/mL (~ 9.0 μM) for the highest concentrations of ERK2 applied to the column. The weight-average molar mass of each of the central major peaks is ~ 42 kDa, which is close to the sequence-derived mass of 41,711 Da for activated ERK2 and therefore corresponds to the ERK2 monomer. The presence of either MgCl2 or CaCl2 up to 10 mM, does not affect the weight-average molar mass of the monomer as ~90-95% of the active ERK2 is monomeric (Fig. 2A & 2B). Fig 2C also shows that in the absence of any divalent cations, activated ERK2 is about 90-95 % monomeric. We used dynamic light scattering (DLS or QELS = Quasi-elastic Light Scattering) to investigate further the self-association of ERK2. The translational diffusion coefficient, D, of a particle may be derived from dynamic light scattering measurements (34, 35). QELS was used to determine the translational diffusion coefficients for tagless active ERK2 applied to a gel filtration column at three concentrations (100, 200 or 300 μM) in the absence of metal ions and at 300 μM in the presence of 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM CaCl2. Analysis by Astra IV software provides the hydrodynamic radius for the fractionated protein (indicated in Fig. 2A-C). The average value over the major peak (~7.2 to 8.8 mL) was used to determine the translational diffusion coefficient using the Stokes-Einstein equation (36). In the presence and absence of free magnesium or calcium ions, the average diffusion coefficient determined by DLS were found to vary over the range of 8.36 to 8.59 × 10-7 cm2/sec. Thus, DLS confirms that the transitional diffusion coefficients of active tagless ERK2, is not affected by the presence of divalent cations or even by varying the concentration of ERK2. A small shoulder can be seen in the elution patterns for the monomeric ERK2 at ~8.1 mL in Fig. 2 but is not apparent in the ERK2 elution pattern in Fig, 6. We interpret the main peak and shoulder to reflect different conformations of ERK2 molecules that do not differ significantly in molar mass. A very similar pattern has been observed by others (16) who interpreted the main peak as a dimer and a shoulder as a monomer on the basis of the Stokes radius. Slightly different shapes or conformations can change the Stokes radius and modify the elution volume with no change at all in the molar mass.

Figure 2. Light-scattering analysis of active tagless ERK2 self-association.

Fractionation of concentrated active ERK2 using size exclusion chromatography followed by MALS-QELS analysis of ERK2 self-association. The chromatographic conditions are given in the Materials and Methods section. A. 20 μL of 300 μM activated ERK2 with 0.5 mM MgCl2 (1, red) and 20 μL of 300 μM activated ERK2 with 10 mM MgCl2 (2, blue) were injected to the column and eluted at concentrations (at the maximum of each peak) of 5.4 and 5.1 μM, respectively. B. 20 μL of 300 μM activated ERK2 with 0.5 mM CaCl2 (3, black) and 20 μL of 300 μM activated ERK2 with 10 mM CaCl2 (4, green) were injected to the column and eluted at concentrations (at the maximum of each peak) of 9 and 8.4 μM, respectively. C. 20 μL of 100 μM (5, red), 200 μM (6, blue) and 300 μM (7, black) active ERK2 with no divalent cations were injected to the column and eluted at concentrations (at the maximum of each peak) of 1.5, 3.4 and 5.4 μM, respectively. The patterns represent the relative concentrations determined by measurement of the refractive index differences, the molar mass distribution and the hydrodynamic Stokes radius (RH), as a function of elution volume.

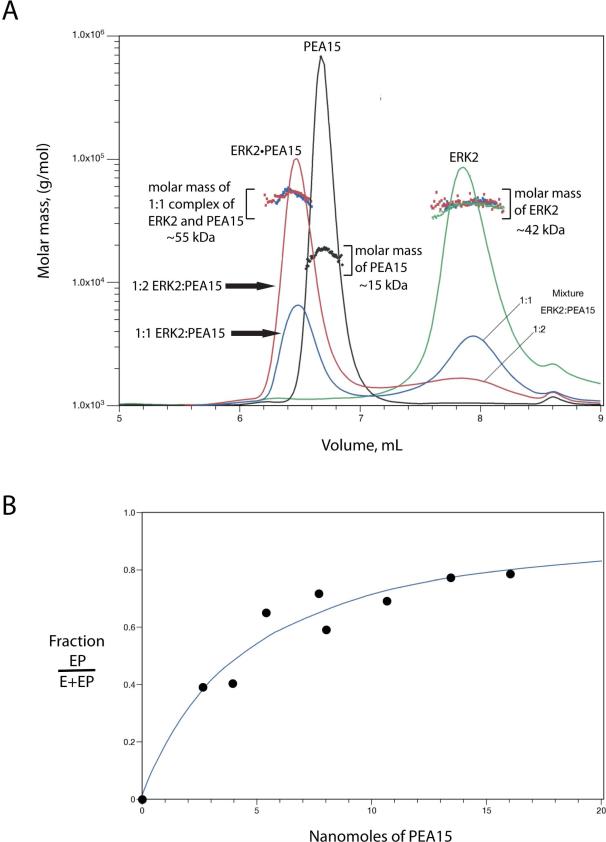

Figure 6. Light scattering analysis of active tagless ERK2/PEA15 mixture following fractionation with a size-exclusion column.

A. Four chromatograms are shown: Active tagless ERK2 alone (~ 300 μM, green line), PEA15 alone (~ 1 mM, black line) and two mixtures of ERK2 and PEA15 at molar ratios of 1:1 (blue line) and 1:2 (red line) respectively by fixing active tagless ERK2 concentration to ~ 300 μM. The 1:1 molar ratio results in a complex of measured molar mass of ~ 55 kDa (ERK2 monomer, 42 kDa, + PEA15, 15 kDa, = 57 kDa). The small peak at 8.6 mL is an artifact present in all samples. The solid lines represent the relative concentrations determined by measurement of the refractive indices. B. Titration of active tagless ERK2 with PEA15. ERK2 (4.35 nanomoles) was titrated with 0 to 16 nanomoles of PEA15. The line corresponds to the best fit to an assumed equilibrium E+P ⇌ E-P. The concentrations seen by the refractometer are about 10-fold lower than those shown.

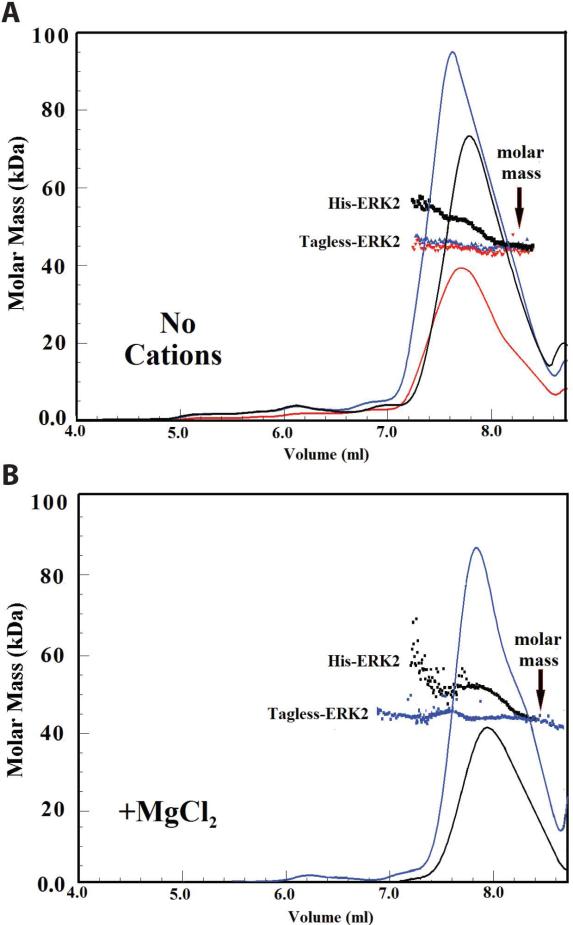

Fig. 3A compares ERK2 with and without a His6-tag. The data show that the His6-tag on ERK2 causes significant dimerization in the absence of added divalent cations. The apparent molar mass at ~ 7.4 mL, ~55 kDa, for the leading edge of the His6-tagged ERK2 peak decreases to ~43 kDa at 8.4 mL. In the absence of the His-tag the molar mass does not change significantly across the elution peak. Fig. 3B shows that the addition of Mg2+ ions has no significant additional effect. The pattern for the His-tagged ERK2 in Fig. 3A can be interpreted in terms of a monomer-dimer equilibrium. A weight-average molar mass of ~55 kDa corresponds to ~30 % dimer. The size-exclusion column acts on a monomer to dimer equilibrium to separate dimer from monomer. However, as the dimer begins to separate from the monomer, it starts to dissociate to reestablish equilibrium according to mass action requirements.

Figure 3. Light-scattering analysis of the effect of the His6-tag on the self-association of ERK2.

Fractionation of active ERK2 with and without a His6-tag shows that the His6-tag on ERK2 causes significant dimerization. (A) shows the molar mass distribution in the absence of added divalent cations; Black: 20 μL of ERK2 (200 μM) with His6-tag; Red: 20 μL of ERK2 (100 μM) without His6-tag; Blue: 20 μL of ERK2 (200 μM) without His6-tag were injected to the column and eluted at concentrations (at the maximum of each peak) of 2.7, 1.5 and 3.4 μM, respectively. (B) shows the molar mass distribution in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2. Black: 20 μL of ERK2 (200 μM) with His6-tag; Blue: 20 μL of ERK2 (300 μM) without His6-tag were injected to the column and eluted at concentrations (at the maximum of each peak) of 2.2 and 5.1 μM, respectively. The chromatographic conditions are the same as in Fig. 2. All experiments were done in the presence of 0.1 mM EDTA.

The experiments described here are with the cleavable His6-tagged ERK2 construct. Prior experiments with non-cleavable His6-tagged ERK2 are shown in Fig. 61 of Ref. 17. These data show that ERK2 with the non-cleavable His6-tag is monomeric in contrast to our data for cleavable His6-tagged ERK2 (Fig. 3) which show that the cleavable His6-tag allows ERK2 to dimerize. Thus the nature of the His6-tag adduct on ERK2 determines its effect on oligomerization.

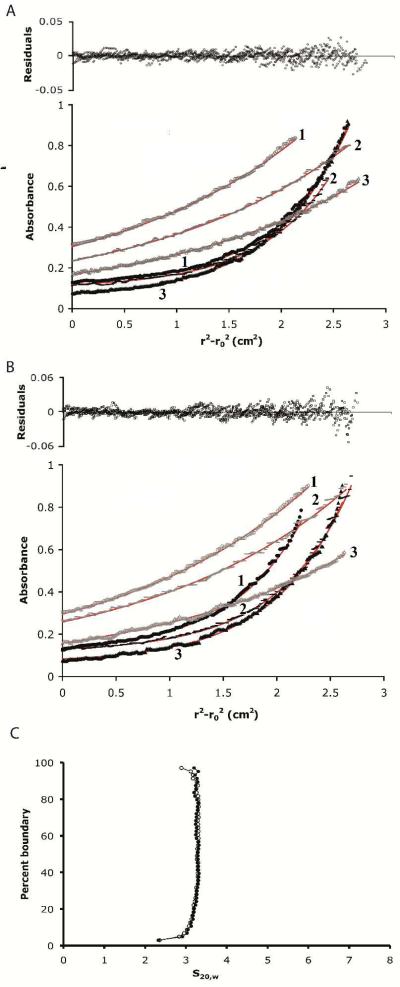

We next examined the self-association of ERK2 by analytical ultracentrifugation. Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed using three different concentrations of tagless ERK2 (ranging from 4.8 to 11.2 μM) at two different rotor speeds in 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA and 1 mM TCEP in the presence or absence of 10 mM MgCl2. TCEP was used instead of DTT, due to the propensity of oxidized DTT to interfere with the detection of proteins at 280 nm. The sedimentation equilibrium data, over the range of concentrations, both in the absence and presence of MgCl2, were well described by an ideal one-component model with a fitted molar mass of 40,180 ± 480 and 41,290 ± 660 Da respectively (Fig. 4A and 4B). This is consistent with the monomeric molar mass of ERK2 of 41,711. Analysis of the data using a monomer-dimer model failed to improve the fit and gives unreasonable dissociation constants of ~ 1 mM for an ERK2 dimer.

Figure 4. Sedimentation analysis of active tagless ERK2.

In a volume of 110 μL activated ERK2 at concentrations of 11.2 μM (1), 8 μM (2) and 4.8 μM (3) were spun at rotor speeds of either 15,000 rpm (grey data points) or 25,000 rpm (black data points) until equilibrium was achieved. The lines through the data correspond to the best fit to an ideal one-component system with the resulting residuals shown above the fits. Buffer contains A, 0 mM MgCl2 and B, 10 mM MgCl2. C. Integral distribution plot showing an enhanced vHW analysis of velocity experiments of 15 μM activated ERK2 in the presence of either 0 mM (•) or 10 mM (○) MgCl2. All sedimentation coefficient values are reported for water at 20 °C.

These results are supported by sedimentation velocity data obtained with a 15 μM solution of activated tagless ERK2. An enhancement (30) of the original method developed by van Holde and Weischet (vHW) (37) was adopted to determine the sedimentation coefficient of ERK2 in the absence and presence of 10 mM MgCl2. The vHW method is particularly suited for distinguishing heterogeneous systems from single component systems (30). Notably, the integral distribution plots shown in Fig. 4C, which are based on the enhanced vHW analysis are virtually identical for the sample of ERK2 in the absence or presence of MgCl2 and provide an average estimate of 3.2S for the sedimentation coefficient of ERK2 in both solutions. Using the generally accepted hydrodynamic non-ideality constant for globular proteins of 0.009 mL/mg, an ERK2 concentration of 0.63 mg/mL, and the experimentally determined s20,w of 3.2S, the value at infinite dilution for ERK2 is calculated to be 3.22S. The of 3.22S (f/f0=1.28) for the activated ERK2 monomer2 is consistent with values determined for other globular proteins such as lysozyme (M = 14,400) and serum albumin (M = 66,000) which exhibit an of 1.91 (f/f= 1.25) and 4.31 (f/f0 = 1.35) respectively (38). The molar mass, M, determined by sedimentation equilibrium, and the sedimentation coefficient, s, may be used to estimate the translational diffusion coefficient D for activated ERK2 using the Svedberg equation (equation 1).

| eqn. 1 |

Using R = 8.314 × 107 g cm2 s-2 and T = 293 K a value of D20,w= 7.3 × 10-7 cm2s-1 is obtained.3 This compares to values of diffusion coefficients reported for lysozyme and bovine serum albumin at 20 °C of 11.2 × 10-7 cm2s-1 and 5.94 × 10-7 cm2s-1 respectively (38). Taken together the analytical ultracentrifugation and DLS experiments argue that phosphorylated ERK2 is monomeric in solution.

The rate of translational diffusion can be determined by 1H NMR from the signal decay that arises from molecular translation occurring during a diffusion delay period that is bracketed by defocusing and refocusing pulsed field gradients (39). Thus, the translational diffusion coefficient of activated tagless ERK2 (55 μM) was determined using this bipolar pulse longitudinal eddy current delay approach in the absence or presence of 10 mM MgCl2 in a buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 2 mM DTT at 25 °C. For comparison, diffusion experiments were also conducted on samples of 1 mM lysozyme and 0.65 mM BSA. The diffusion coefficients were obtained by fitting the decay of the protein 1H signal intensity as a function of defocusing/refocusing gradient strengths as shown in Fig 5. The measured translational diffusion coefficient at 25 °C for activated ERK2 was determined to be 8.7 ± 0.4 × 10-7 cm2s-1 in the presence or absence of MgCl2 and the translational diffusion coefficients for BSA and lysozyme were 6.8 ± 0.1 and 12.9 ± 0.1 × 10-7 cm-2s-1, respectively (Fig. 5). These data demonstrate that activated tagless ERK2 diffuses faster than BSA (66 kDa) and slower than lysozyme (14.7 kDa) and supports the notion that ERK2 is a monomer in solution at a concentration of 55 μM. The experimentally determined translational diffusion coefficient for ERK2 from NMR is in excellent agreement with the values calculated from the sedimentation and DLS experiments.

Figure 5. Translational diffusion attenuation of 1H NMR signal intensity for active tagless ERK2 in the absence of MgCl2.

The self-diffusion coefficient (Ds) is obtained from a fit of the signal decay to the relationship I/Io = exp[-γ2G2δ2(Δ-δ/3)/Ds], where G = gradient strength (G/cm) and I = the echo amplitude. Logarithmic (normalized) signal intensities for activated ERK2 (Δ), bovine serum albumin (Ο) and lysozyme (□) from a single experiment.

Although our DLS, sedimentation and NMR data show that ERK2 is monomeric, the possibility that accessory proteins might mediate the dimerization of ERK2 cannot be ignored. Cytoplasmic scaffolds have been reported to induce dimerization of ERK2 (40). We examined the possibility that ERK2 and the small cytoplasmic scaffold PEA-15 (27) interact. We used the same approach as described for the ERK2 self-association studies shown in Fig. 2. Active ERK2 was applied to the column at a concentration of ~ 300 μM. As before, Fig. 6A shows that the enzyme is predominantly monomeric at this high concentration in the absence of MgCl2. Based on their amino acid compositions the calculated molar masses of ERK2 and PEA-15 are 41,717 Da and 15,321 Da respectively. Fig. 6A shows that the much smaller PEA-15, ~ 15 kDa, elutes (~ 6.7 mL) from the size-exclusion column before the larger ERK2, ~ 42 kDa, (~7.9 mL). This reflects the extended conformation of PEA-15 (41) and emphasizes that molar masses cannot be accurately determined solely from elution volumes. A mixture of ERK2 and PEA-15 results in the formation of a complex that elutes at ~ 6.4 mL with a molar mass of ~ 55 kDa as determined by MALS, close to the expected mass of 57 kDa for the E-P complex. This finding supports a 1:1 stoichiometry for the ERK2•PEA15 complex (E-P).

A titration of ERK2 with PEA15 was made by making mixtures of known composition and subjecting them to MALS analysis after fractionation on the size-exclusion column. The quantity of the complex cannot be estimated directly because the peak for the complex overlaps with the elution of free PEA15 Fig. 6A). Measuring the concentration of free ERK2 and subtracting it from the known total amount of ERK2 in the composition of the initial mixture according to [E – P] = Et – Ef where Et and Ef are the total and free nanomoles of ERK2, respectively allowed the amount of the complex to be estimated. The fraction of ERK2 with bound PEA15 was estimated from the ratio (Et – Ef)/Et. Fig. 6B shows the titration of ERK2 with increasing amounts of PEA-15. The line corresponds to the best fit to an assumed equilibrium: E + P ⇌ E-P. It should be noted that this is a titration and would represent a measure of a true equilibrium only if the rates of association and dissociation were extremely slow. The titration data support the stoichiometry of one molecule of PEA-15 forming a complex with one molecule of ERK2. The molar mass of the complex, ~55, 000 Da, measured by MALS is close to the value expected for 1:1 stoichiometry, 57,038 Da.

DISCUSSION

Activated ERK2 is a monomer in the absence or presence of divalent cations

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the self-association of activated ERK2 in the presence or absence of divalent cations. X-ray crystallographic studies have revealed a potential interface for the stabilization of ERK2 homodimers by a non-helical leucine zipper composed of L333, L334, and L336 from each monomer (16). However, previous reports concerning the self-association of ERK2 in solution have been contradictory (15-17). Activated His6-ERK2 monomers were initially reported by Khokhlatchev et al. (15) to self-associate with high affinity (dissociation constant, Kd = 7 nM) in the absence of added divalent metal ions. However, Wilsbacher et al. (16) and Callaway et al. (17) later reported that His6-ERK2 is monomeric in the presence of chelating agents such as EDTA and EGTA. While dimerization was reported to be partially restored by the addition of divalent magnesium or calcium ions (16), the possibility was not addressed that trace transition metals promote dimerization of His6-ERK2 in the absence of chelating agents, potentially through coordination to the His6-tag. We have now assessed the possibility that activated tagless ERK2 might self-associate to form a homodimer. Activated ERK2 without the His6-tag is fully active when assayed with the transcription factor substrate Ets (Fig 1).

Several complementary biophysical techniques were used to determine whether activated ERK2 forms specific homodimers (Figs 2-6). These techniques, taken together, provide a convincing description of activated ERK2 as a monomer in solution at concentrations an order of magnitude higher than the 50-1000 nM normally found in mammalian cells (42).

Gel filtration and analysis of the eluted proteins by light scattering is a useful way to measure self-association (43-45). Light scattering is necessary because elution volumes are very sensitive to conformation and ionic conditions and cannot be relied upon to yield accurate molar masses (45, 46). Light scattering is particularly helpful for characterizing polydisperse solutions of proteins that may result from significant aggregation. No significant self-association was observed in the presence of 0.5 mM or 10 mM free Mg2+ or Ca2+ ions (Fig. 2A and 2B). Similarly, the monomeric fraction exceeded ~90% when ERK2 was loaded onto the SEC column at concentrations of 100, 200 or 300 μM in the absence of free divalent cations.4 Moreover, QELS analysis indicates that the hydrodynamic radius (RH(23,W)) of ~2.8 nm for ERK2 is unaffected by the presence or absence of divalent cations (Fig. 2A-C). This suggests that divalent cations do not affect ERK2 self-association either at physiological or saturating concentration.

Possible self-association of ERK2 was studied further with sedimentation equilibrium and velocity experiments, which are important approaches for examining the association of oligomers (45, 46). The longer experimental timescale of the sedimentation experiments makes possible the resolution of slowly equilibrating non-specific aggregates (45, 46). Neither the sedimentation equilibrium nor the velocity experiments were able to detect any significant self-association of ERK2 either in the presence or absence of magnesium ions (Fig. 4). The equilibrium experiments were fitted with a single species of ~ 42 kDa (Fig. 4A and 4B). A sedimentation coefficient of ~ 3.22 S was calculated from the velocity data (Fig. 4C). The frictional coefficient ratio (f/f0) was calculated to be 1.28 for monomeric activated ERK2 which lies in the range of 1.20–1.40 generally observed for globular proteins. The translational diffusion coefficient, D, was calculated to be ~8.3 × 10-7 cm2s-1 for the activated ERK2 monomer. This finding was supported by dynamic light scattering, which also showed a translational diffusion coefficient D ~ 8.3 × 10-7 cm2s-1 for ERK2 under all the experimental conditions. Furthermore, the NMR experiments showed a similar translational diffusion coefficient of D = 8.7 ± 0.4 × 10-7 cm2s-1 at 55 μM activated ERK2 (Fig. 5). The excellent agreement between these three biophysical techniques in determination of the translational diffusion coefficient confirms that phosphorylated ERK2 is monomeric in the presence or absence of divalent cations and at different ERK2 concentrations (100-300 μM).

How does ERK2 associate with a cytoplasmic scaffold?

Studies of the self-association of ERK2 in vivo are contradictory. A FRET-based study failed to identify dimerization of activated GFP-ERK2 in cells (18). A genetically encoded bioluminescence probe containing two ERK2 monomers joined by a linker was used as evidence for dimerization (47). However, this latter approach is not a freely reversible process as the bioluminescence is dependent on the irreversible formation of Renilla luciferase and the monomers are present in the same polypeptide. Casar et al. (19) used the approach of Philipova and Whitaker (48) to report that ERK2 forms a homodimer on cytoplasmic scaffolds and substrates. They also report that only a monomer forms on nuclear substrates. We used static light-scattering to examine the propensity of ERK2 to form a homodimer in association with the cytoplasmic scaffold PEA15. Fig. 6 clearly demonstrates that ERK2 and PEA-15 form a 1:1 complex of 57 kDa and that ERK2 is a monomer in this complex.

We have shown with three approaches that ERK2 has virtually no propensity to self-associate in the presence of physiological concentrations of either magnesium or calcium ions. Thus, if ERK2 dimerizes to cytoplasmic scaffolds an underlying mechanism of selectivity must be associated with the process.

The method employed by Caser et al. (19), which was first used by Philipova and Whitaker for the identification of ERK dimers in vivo (48) requires incubating the proteins under non-reducing conditions where they have a propensity to cross-link with disulfide bonds. As many mechanisms can bring two proteins to within close enough proximity to chemically cross-link in a cellular lysate, such an approach can be misinterpreted. Most of the evidence supporting the importance of ERK2 homodimerization in solution utilizes the mutations originally identified by Khokhlatchev et al. (15). These mutants were designed to break the putative homodimer interface seen in the crystal structure (32). However, caution is needed when interpreting experiments with these mutants as their translocation to the nucleus (which is not dependent on dimerization) is impeded (40) and similar mutations in ERK1 render the protein unrecognizable by a phosphospecific antibody (48). This suggests that the mutations may alter their ability to interact with other proteins.

Conclusion

The ability of activated ERK2 to self-associate into specific homodimers at micromolar concentrations is not supported by a number of complementary biophysical techniques. Thus, ERK2 is unlikely to form specific homodimers in vivo at physiological concentrations. Although His6-tagged ERK2 can form dimers under certain conditions, the tag is non-physiological and so the dimers formed have no cellular significance. In addition, the assembly of activated ERK2 homodimers onto cytoplasmic scaffolds is not a general phenomenon. Further experimental work is required to establish whether such homodimers can form through co-operative interactions with scaffold proteins in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the excellent technical support from Claire Riggs. Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments were carried out in the Protein Analysis Facility of the Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology (ICMB) at the University of Texas at Austin. Mass spectra were acquired by Herng-Hsiang Lo in the CRED Analytical Instrumentation Facility Core at the University of Texas at Austin.

This research was supported in part by the grants from the Welch Foundation (F-1390) to KND and the National Institutes of Health to KND (GM59802). T.S.K. acknowledges a scholarship from the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education. Light-scattering instrumentation was funded by National Science Foundation (Grant MCB-0237651 to A. F. Riggs).

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin fraction V

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis[2-aminoethyl ether]-N,N,N’N’-tetra-acetic acid

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- Ets

murine His6-tagged Ets-1 (1-138)

- FPLC

fast protein liquid chromatography

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazine-N’-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- HIC

hydrophobic interaction column

- IAA

iodoacetamide

- IEG

immediate early genes

- IPTG

isopropyl-ß-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal Kinase

- MALS-QELS

multi-angle-quasi-elastic light scattering

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MKK1

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1

- MKK6

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PEA-15

astrocytic phosphoprotein

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride

- SAP1/2

SRF accessory protein-1/2

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TCEP

(tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride)

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TPCK

tosylphenylalanylchloromethane

- TRIS

tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane

Footnotes

The ordinate of Fig. 6 in ref. 17 is logarithmic and is labelled incorrectely. The label numbers 40, 50, and 60 should be changed to 10, 100, and 1000.

If ERK2 behaves as a perfect unhydrated sphere sedimenting in pure water, the frictional coefficient, f0, may be calculated from using the following parameters; viscosity of the water (η) = 1.002 × 10-2 poise, molecular weight (M) = 41,290 g mol-1 (obtained from the sedimentation equilibrium experiment), partial specific volume of ERK2 () = 0.7403 mL/g, and Avogadro's number NA = 6.023 × 1023 mol-1. The actual frictional coefficient, f, for ERK2 undergoing sedimentation in water may be derived from the experimentally determined parameters using where ρ is the density of water (0.9982 g mL-1), s is the sedimentation coefficient at 20 °C in water determined by sedimentation velocity and M is the molecular weight determined by sedimentation equilibrium. Together these calculations provide an estimate for the frictional coefficient ratio of activated ERK2 of f/f0 = 1.28, which is as expected for globular proteins.

This corresponds to a D25,w of 8.3 × 10-7 cm2s-1.

A small amount of polydisperse material that elutes slightly earlier than the monomeric fraction may be observed when activated ERK2, that has been further purified by HIC, is applied to a SEC column at a concentration of ~ 300 μM in the absence of divalent metal ions.

References

- 1.Chen Z, Gibson TB, Robinson F, Silvestro L, Pearson G, Xu B, Wright A, Vanderbilt C, Cobb MH. MAP kinases. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2449–76. doi: 10.1021/cr000241p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaoud TS, Mitra S, Lee S, Taliaferro J, Cantrell M, Linse KD, Vandenberg CL, Dalby KN. Development of JNK2-Selective Peptide Inhibitors that Inhibit Breast Cancer Cell Migration. ACS Chem Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1021/cb200017n. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–65. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avruch J, Zhang XF, Kyriakis JM. Raf meets Ras: completing the framework of a signal transduction pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:279–83. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong H, Vikis HG, Guan KL. Mechanisms of regulating the Raf kinase family. Cell Signal. 2003;15:463–9. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreck R, Rapp UR. Raf kinases: oncogenesis and drug discovery. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2261–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng CF, Guan KL. Cloning and characterization of two distinct human extracellular signal-regulated kinase activator kinases, MEK1 and MEK2. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11435–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrell JE, Jr., Bhatt RR. Mechanistic studies of the dual phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19008–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.19008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunet A, Roux D, Lenormand P, Dowd S, Keyse S, Pouyssegur J. Nuclear translocation of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for growth factor-induced gene expression and cell cycle entry. EMBO J. 1999;18:664–74. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen RH, Chung J, Blenis J. Regulation of pp90rsk phosphorylation and S6 phosphotransferase activity in Swiss 3T3 cells by growth factor-, phorbol ester-, and cyclic AMP-mediated signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1861–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalby KN, Morrice N, Caudwell FB, Avruch J, Cohen P. Identification of regulatory phosphorylation sites in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinase-1a/p90rsk that are inducible by MAPK. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1496–505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leighton IA, Dalby KN, Caudwell FB, Cohen PT, Cohen P. Comparison of the specificities of p70 S6 kinase and MAPKAP kinase-1 identifies a relatively specific substrate for p70 S6 kinase: the N-terminal kinase domain of MAPKAP kinase-1 is essential for peptide phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 1995;375:289–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01170-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marais R, Wynne J, Treisman R. The SRF accessory protein Elk-1 contains a growth factor-regulated transcriptional activation domain. Cell. 1993;73:381–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90237-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price MA, Rogers AE, Treisman R. Comparative analysis of the ternary complex factors Elk-1, SAP-1a and SAP-2 (ERP/NET) EMBO J. 1995;14:2589–601. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khokhlatchev AV, Canagarajah B, Wilsbacher J, Robinson M, Atkinson M, Goldsmith E, Cobb MH. Phosphorylation of the MAP kinase ERK2 promotes its homodimerization and nuclear translocation. Cell. 1998;93:605–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilsbacher JL, Juang YC, Khokhlatchev AV, Gallagher E, Binns D, Goldsmith EJ, Cobb MH. Characterization of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) dimers. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13175–82. doi: 10.1021/bi061041w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaway KA, Rainey MA, Riggs AF, Abramczyk O, Dalby KN. Properties and regulation of a transiently assembled ERK2.Ets-1 signaling complex. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13719–33. doi: 10.1021/bi0610451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burack WR, Shaw AS. Live Cell Imaging of ERK and MEK: simple binding equilibrium explains the regulated nucleocytoplasmic distribution of ERK. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3832–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casar B, Pinto A, Crespo P. Essential role of ERK dimers in the activation of cytoplasmic but not nuclear substrates by ERK-scaffold complexes. Mol Cell. 2008;31:708–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J, Filutowicz M. Hexahistidine (His6)-tag dependent protein dimerization: a cautionary tale. Acta Biochim Pol. 1999;46:591–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amor-Mahjoub M, Suppini JP, Gomez-Vrielyunck N, Ladjimi M. The effect of the hexahistidine-tag in the oligomerization of HSC70 constructs. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;844:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szafranska AE, Luo X, Dalby KN. Following in vitro activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by mass spectrometry and tryptic peptide analysis: purifying fully activated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase alpha. Anal Biochem. 2005;336:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueda EK, Gout PW, Morganti L. Current and prospective applications of metal ion-protein binding. J Chromatogr A. 2003;988:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)02057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abramczyk O, Rainey MA, Barnes R, Martin L, Dalby KN. Expanding the repertoire of an ERK2 recruitment site: cysteine footprinting identifies the D-recruitment site as a mediator of Ets-1 binding. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9174–86. doi: 10.1021/bi7002058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waas WF, Rainey MA, Szafranska AE, Dalby KN. Two rate-limiting steps in the kinetic mechanism of the serine/threonine specific protein kinase ERK2: a case of fast phosphorylation followed by fast product release. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12273–86. doi: 10.1021/bi0348617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callaway K, Rainey MA, Dalby KN. Quantifying ERK2-protein interactions by fluorescence anisotropy: PEA-15 inhibits ERK2 by blocking the binding of DEJL domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callaway K, Abramczyk O, Martin L, Dalby KN. The anti-apoptotic protein PEA-15 is a tight binding inhibitor of ERK1 and ERK2, which blocks docking interactions at the D-recruitment site. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9187–98. doi: 10.1021/bi700206u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laue TM, Shah BD, Ridgeway TM, Pelletier SL. Computer-aided Interpretation of Anaytical Sedimentation Data for Proteins. In: Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. RCS; Cambridge: 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demeler D. UltraScan – a comprehensive data analysis software for analytical ultracentrifugation experiments. In: Scott David J., Harding SE, Rowe Arthur J., editors. Analytical ultracentrifugation : techniques and methods. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 2005. pp. 210–229. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demeler B, van Holde KE. Sedimentation velocity analysis of highly heterogeneous systems. Anal Biochem. 2004;335:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu D, Chen A, Johnson CS., Jr An improved diffusion-ordered spectroscopy experiment incorporating bipolar-gradient pulses. J. Magn. Reson A. 1995;115:260–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canagarajah BJ, Khokhlatchev A, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Activation mechanism of the MAP kinase ERK2 by dual phosphorylation. Cell. 1997;90:859–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waas WF, Dalby KN. Purification of a model substrate for transcription factor phosphorylation by ERK2. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;23:191–7. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Jaeger N, Demeyere H, Finsy R, Sneyders R, van der Meeren P, van Laethem M. Particle Sizing by Photon Correlation Sectroscopy Part I: Monodisperse latices: influence of scattering angle and concentration of dispersed material. Particle & Particle Systems Characterization. 1991;8:179–86. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burchard W. Combined Static and Dynamic Light Scattering. In: Brown W, editor. Light scattering: principles and development. Clarendon; Oxford: 1996. pp. 439–76. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Will S. a. L., A. Measurement of particle diffusion coefficients with high accuracy by dynamic light scattering. Progr Colloid Polym Sci. 1997;104:110–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Holde KE, Weischet WO. Boundary analysis of sedimentation velocity experiments with monodisperse and paucidisperse solutes. Biopolymers. 1978;17:1387–403. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Holde KE, Johnson WC, Ho PS. Principles of physical biochemistry. International ed. 2nd ed. Pearson/Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, N.J. ; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia de la Torre J, Huertas ML, Carrasco B. HYDRONMR: prediction of NMR relaxation of globular proteins from atomic-level structures and hydrodynamic calculations. J Magn Reson. 2000;147:138–46. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casar B, Arozarena I, Sanz-Moreno V, Pinto A, Agudo-Ibanez L, Marais R, Lewis RE, Berciano MT, Crespo P. Ras subcellular localization defines extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 substrate specificity through distinct utilization of scaffold proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1338–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01359-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farina B, Pirone L, Russo L, Viparelli F, Doti N, Pedone C, Pedone EM, Fattorusso R. NMR backbone dynamics studies of human PED/PEA-15 outline protein functional sites. FEBS J. 2010;277:4229–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang CY, Ferrell JE., Jr. Ultrasensitivity in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10078–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Folta-Stogniew E, Williams KR. Determination of molecular masses of proteins in solution: Implementation of an HPLC size exclusion chromatography and laser light scattering service in a core laboratory. J Biomol Tech. 1999;10:51–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winzor DJ. Analytical exclusion chromatography. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2003;56:15–52. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(03)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Philo JS. Is any measurement method optimal for all aggregate sizes and types? AAPS J. 2006;8:E564–71. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lebowitz J, Lewis MS, Schuck P. Modern analytical ultracentrifugation in protein science: a tutorial review. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2067–79. doi: 10.1110/ps.0207702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaihara A, Umezawa Y. Genetically encoded bioluminescent indicator for ERK2 dimer in living cells. Chem Asian J. 2008;3:38–45. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Philipova R, Whitaker M. Active ERK1 is dimerized in vivo: bisphosphodimers generate peak kinase activity and monophosphodimers maintain basal ERK1 activity. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5767–76. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]