Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to summarize mode of action of cisplatin on the tumor cells, a brief outlook on the metallocene compounds as antitumor drugs as well as the future tendencies for the use of the latter in anticancer chemotherapy. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin interaction with DNA, DNA repair mechanisms, and cellular proteins are discussed. Molecular background of the sensitivity and resistance to cisplatin, as well as its influence on the efficacy of the antitumor immune response was evaluated. Furthermore, herein are summarized some metallocenes (titanocene, vanadocene, molybdocene, ferrocene, and zirconocene) with high antitumor activity.

1. Cisplatin

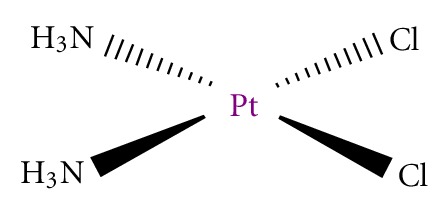

Since 1845, when Italian doctor Peyrone synthesized cisplatin (Figure 1), through Rosenberg's discovery of cisplatin antiproliferative potential [1], and subsequent approval for clinical usage in 1978, this drug is considered as most promising anticancer therapeutic [2, 3]. Cisplatin is highly effective against testicular, ovarian, head and neck, bladder, cervical, oesophageal as well as small cell lung cancer [4].

Figure 1.

Cisplatin.

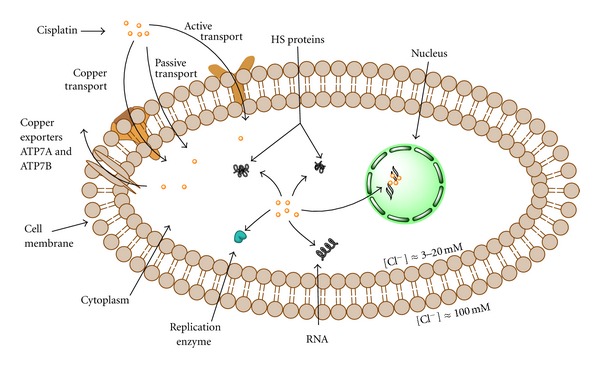

For more than 150 years, first exaltation about this “drug of the 20th century” was replaced with discouraging data about its toxicity and ineffectiveness got from clinical practice. It was found that cisplatin induced serious side effects such as nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, nausea, and vomiting [5]. General toxicity and low biological availability restricted its therapeutically application. In addition, it is known that some tumors such as colorectal and nonsmall lung cancers are initially resistant to cisplatin while other like ovarian and small cell lung cancers easily acquired resistance to drug [6]. Numerous examples from in vitro studies confirmed that exposure to cisplatin often resulted in development of apoptotic resistant phenotype [7–9]. Following this, development of cisplatin resistant cell lines is found useful for testing the efficacy of future cisplatin modified drugs and on the other hand for evaluation of mechanisms involved in development of resistance. For better understanding of unresponsiveness to cisplatin, it is necessary to define the exact molecular targets of drug action from the moment of entering tumor cell. It is proposed the intact cisplatin which avoided bounding to plasma proteins enter the cell by diffusion or active transport via specific receptors (Figure 2) [10, 11]. Cisplatin is able to use copper-transporting proteins to reach intracellular compartments [12–14]. In addition, regarding to its chemical reactivity, cisplatin can influence cell physiology even through interaction with cell membrane molecules such as different receptors.

Figure 2.

Cisplatin and the cell: transport/export and targets.

1.1. Cisplatin and DNA

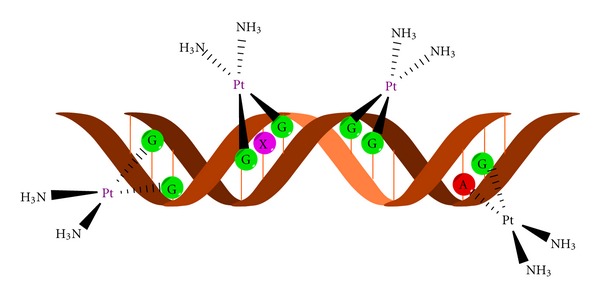

Although it is known that DNA is a major target for cisplatin, only 5–10% intracellular concentration of cisplatin is found in DNA fraction while 75–85% binds to nucleophilic sites of intracellular constituents like thiol containing peptides, proteins, replication enzymes, and RNA [6, 15–17]. This preferential binding to non-DNA targets offers the explanation for cisplatin resistance but also its high toxicity. Prerequisite of efficient formation of cisplatin DNA adducts is hydratization of cisplatin enabled by low chloride ions content inside the cells [18]. N7 of guanine and in less extend adenine nucleotide are targeted by platinum [19]. Binding of cisplatin to DNA is irreversible and structurally different adducts are formed. The adducts are classified as intrastrand crosslinking of two nucleobases of single DNA strand, interstrand crosslinking of two different strands of one DNA molecule, chelate formation through N- and O-atoms of one guanine, and DNA-protein crosslinks [20, 21]. Cisplatin forms about 65% pGpG-intrastrand crosslinks, 25% pApG-intrastrand crosslinks, 13% interstrand or intrastrand crosslinks on pGpXpG sequences, and less than 1% of monofunctional adducts (Figure 3) [22]. Crucial role of 1,2-intrastrand crosslinks in antitumor potential of the cisplatin is supported by two facts. First, high mobility group proteins (HMG) specifically recognize this type of cisplatin-DNA interaction and second, these adducts are less efficiently removed by repair enzymes [17]. In addition, important mediators of cisplatin toxicity are ternary DNA-platinum-protein crosslinks (DPCL) whose frequency is dependent from the cell type as well as the type of the treatment. DPCLs inhibited DNA polymerization or their own removal by nucleotide excision repair system more potently than other DNA adducts [17]. In fact, cisplatin DNA adducts can be repaired by nucleotide excision repair proteins (NER), mismatch repair (MMR), and DNA-dependent protein kinases protein [17].

Figure 3.

DNA adduct formation with cisplatin moiety.

1.2. DNA Repair Mechanism

Nucleotide excision repair proteins are ATP-dependent multiprotein complex able to efficiently repair both inter as well as intrastrand DNA-cisplatin adducts. Successful repair of 1,2-d(GpG) and 1,3-d(GpNpG) intrastrand crosslinks has been found in different human and rodent NER systems [23, 24]. This repair mechanism is able to correct the lesions promoted by chemotherapeutic drugs, UV radiation as well as oxidative stress [17]. Efficacy of NER proteins varying in different type of tumors and is responsible for acquirement of cisplatin resistance. Low level of mentioned proteins is found in testis tumor defining their high sensitivity to cisplatin treatment. Oppositely, ovarian, bladder, prostate, gastric, and cervical cancers are resistant to cisplatin based therapy due to overexpression of several NER genes [25, 26].

Mismatch repair (MMR) proteins are the post replication repair system for correction of mispaired and unpaired bases in DNA caused by DNA Pt adducts. MMR recognized the DNA adducts formed by ligation of cisplatin but not oxaliplatin [27–30]. Defective MMR is behind the resistance of ovarian cancer to cisplatin and responsible for the mutagenicity of cisplatin [31].

DNA dependent protein kinase is a part of eukaryotic DNA double strand repair pathway. This protein is involved in maintaining of genomic stability as well as in repair of double strand breaks induced by radiation [31]. In ovarian cancer presence of cisplatin DNA adducts inhibited translocation of DNA-PK subunit Ku resulting in inhibition of this repair protein [32].

Special attention is focused on recognition of cisplatin-modified DNA by HMG proteins (HMG). It is hypothesized that HMG proteins protected adducts from recognition and reparation [17, 31]. Moreover, it was postulated that these proteins modulate cell cycle events and triggered cell death as a consequence of DNA damage. One of the members from this group marked as HMGB1 is involved in MMR, increased the p53 DNA-binding activity and further stimulated binding of different sequence specific transcription factors [33]. Few studies revealed that cisplatin sensitivity was in correlation with HMGB level, while other studies eliminated its significance in response to cisplatin treatment. Contradictory data about the relevance of HMG proteins in efficacy of cisplatin therapy indicated that this relation is defined by cell specificity.

1.3. Cytotoxicity of Cisplatin

Other non-HMG nuclear proteins are also involved in cytotoxicity of cisplatin. Presence of cisplatin DNA adducts is able to significantly change or even disable the primary function of nuclear proteins essential for transcription of mammalian genes (TATA binding protein, histon-linker protein H1 or 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase mammalian repair protein) [34–36].

Although cytotoxicity of cisplatin is usually attributed to its reactivity against DNA and subsequent lesions, the fact that more than 80% of internalized drug did not reach DNA indicated the involvement of numerous non-DNA cellular targets in mediation of cisplatin anticancer action [6]. As a consequence of exposure to cisplatin, different signaling pathways are affected. There is no general concept applicable to all types of tumor. It is evident that response to cisplatin is defined by cell specificity. Numerous data revealed changes in activity of most important signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and cell death such as PI3K/Akt, MAPK as well as signaling pathways involved in realization of death signals dependent or independent of death receptors [33]. It is very important to note that alteration in signal transduction upon the cisplatin treatment could be the consequence of both, DNA damage or interaction with exact protein or protein which is relevant for appropriate molecular response. Some of the interactions between protein and cisplatin are already described. Therefore, it was found that cisplatin directly interacts with telomerase, an enzyme that repairs the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes [31, 37]. In parallel, cisplatin-induced damage of telomeres which are not transcribed and therefore hidden from NER. Other important protein targeted by cisplatin is small, tightly folded molecule known as ubiquitin (Ub) [38]. Ub is implicated in selective degradation of short-lived cellular proteins [39]. It has been hypothesized that direct interaction of cisplatin with this protein presented a strong signal for cell death [40]. Two binding sites were identified as target for cisplatin ligation: N-terminal methionine (Met1) and histidine at position 68, while the drug makes at least four types of adducts with protein [38]. This resulted in disturbed proteasomal activity and further cell destruction. Having in mind that proteasomal inactivation by specific inhibitors showed promising results in cancer treatment, this aspect of cisplatin reactivity can be leading cytotoxic effect even to be more powerful than DNA damage [41]. One of the crucial molecules involved in propagation of apoptotic signal through depolarization of mitochondrial potential—cytochrome c is also targeted by cisplatin on Met65 [42]. Further, on the list of protein or peptide targets for cisplatin are glutathione and metallothioneins, superoxide dismutase, lysozyme as well as extracellular protein such as albumin, transferrin, and hemoglobin [43]. Some of mentioned interactions served as drug intracellular pool while their biological relevance is still under investigation.

1.4. Activation of Signaling Pathways Induced with Cisplatin

DNA damage induced by cisplatin represent strong stimulus for activation of different signaling pathways. It was found that AKT, c-Abl, p53, MAPK/JNK/ERK/p38 and related pathways respond to presence of DNA lesions [31, 33]. AKT molecule as most important Ser/Thr protein kinase in cell survival protects cells from damage induced by different stimuli as well as cisplatin [44]. Cisplatin downregulated XIAP protein level and promoted AKT cleavage resulting in apoptosis in chemosensitive but not in resistant ovarian cancer cells [45, 46]. Recently published data about synergistic effect of XIAP, c-FLIP, or NFkB inhibition with cisplatin are mainly mediated by AKT pathway [47].

Protein marked as the most important in signaling of the DNA damage is c-Abl which belongs to SRC family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases [31, 33]. This molecule acts as transmitter of DNA damage triggered by cisplatin from nucleus to cytoplasm [48]. Moreover, sensitivity to cisplatin induced apoptosis is directly related with c-Abl content and could be blocked by c-Abl overexpression [33]. Key role of c-Abl in propagation of cisplatin signals is confirmed in experiments with ABL deficient cells [49]. It was found that cisplatin failed to activate p38 and JNK in the absence of c-Abl. Homology of this kinases with HMGB indicated the possibility that c-Abl recognized and interact with cisplatin DNA lesions like HMGB1 protein [31].

1.5. The Role of the Functional p53 Protein

Evaluation of a 60 cell line conducted by the National Cancer Institute revealed that functional p53 protein is very important for successful response to cisplatin treatment [33]. This tumor suppressor is crucial for many cellular processes and determined the balance between cell cycle arrest as a chance for repair and induction of apoptotic cell death [33]. However, despite extensive NCI study, there are controversial data about correlation between cisplatin sensitivity and p53. For example, it was found that functional p53 was associated with amplified cisplatin sensitivity in SaOS-2 osteosarcoma cells in high serum growth conditions while the opposite relation was observed upon starvation [33]. This phenomenon could be connected to autophagic process triggered in serum deficient conditions, which in turn downregulate cisplatin promoted apoptosis [50]. In some other studies, the response to cisplatin was not influenced by p53. It is indicative that antitumor potential of cisplatin and its interaction with p53 is a question of multiple factors such as tumor cell type, specific signaling involved in cancerogenesis, as well as other genetic alterations. In addition, protein involved or influenced by p53 pathway such as Aurora kinase A, cyclin G, BRCA1 as well as proapoptotic or antiapoptotic mediators are also able to control cisplatin toxicity [33].

1.6. Relation between Cisplatin and Mitogen-Activated Protein (MAP) Kinases

Finally, signaling pathways mediated by mitogen-activated kinases are strongly influenced by cisplatin. These enzymes are highly important in definition of cellular response to applied treatment because they are the major regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation, and cell death. ERK (extracellular signal-related kinase) preferentially responds to growth factor and cytokines but also determines cell reaction to different stress conditions, particularly, oxidative [33]. Cisplatin treatment mainly activated ERK in a dose- and time-dependent manner [33, 51, 52]. However, like as previously described, changes in ERK activity upon the exposure to cisplatin varying from type to type of the malignant cell and is defined by their intrinsic features. Following this, in some circumstances ERK activation antagonized cisplatin toxicity. In cells with significant upregulation of ERK activity in response to cisplatin treatment, exposure to specific MEK1 inhibitor PD98052 abrogated its toxicity. Also, development of the resistance to the cisplatin in HeLa cells is connected with reduced ERK response to the treatment [52]. Moreover, combined treatment with some of the naturally occurring compounds such as aloe-emodin-neutralized cisplatin toxicity through inhibition of ERK, indicated possible negative outcome of combining of conventional and phytotherapy [53, 54].

Regardless of numerous evidences about its critical role in cisplatin-mediated cell death, ERK is not the only molecule from MAP family which responded to cisplatin. Several studies revealed JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) activation upon the cisplatin addition [55, 56]. However, similarly to other molecules previously mentioned this signal is not the unidirectional and could be responsible for realization but also protection from death triggered by the cisplatin [57, 58]. Finally, there are numerous evidences about highly important role of third member of MAP kinases, p38, in response to cisplatin [59, 60]. Lack of p38 MAPK leads to appearance of resistant phenotype in human cells [55, 60]. Early and short p38 activation is principally described in cells unresponsive to cisplatin while long-term activation was found in sensitive clones. Moreover, in the light of the fact that this kinase has a role in modifying the chromatin environment of target genes, its involvement in cisplatin-induced phosphorilation of histon 3 was determined [61].

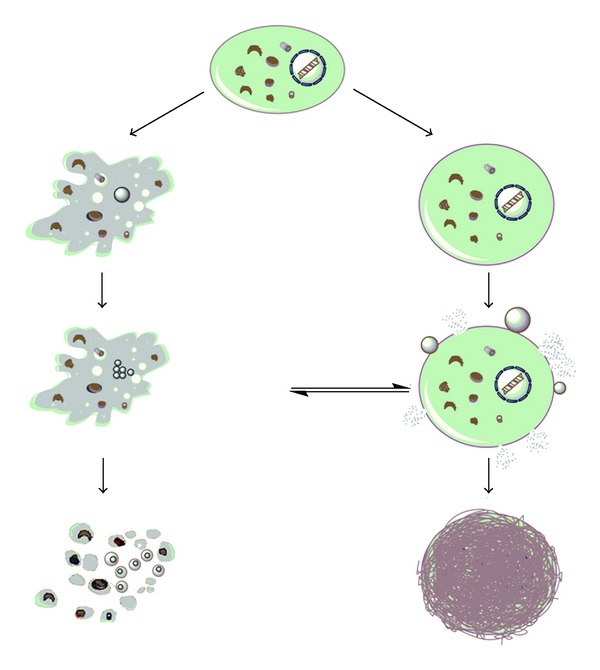

1.7. On the Mode of Cell Death Induced by Cisplatin

The net effect of intracellular interaction of cisplatin with DNA and non-DNA targets is the cell cycle arrest and subsequent death in sensitive clones. There are two type of death signals resulting from cellular intoxication by this drug (Figure 4). Fundamentally, the drug concentration presents the critical point for cell decision to undergo apoptotic or necrotic cell death [62]. Primary cultures of proximal tubular cells isolated from mouse died by necrosis if they were exposed to high doses of cisplatin just for a few hours while apoptotic cell death is often triggered by long-term exposure to significantly lower concentrations [63]. However, the presence of necrosis in parallel with apoptosis in tumor-cell population indicated that type of cell death is not just the question of dose but also is defined by cell intrinsic characteristics and energetic status of each cell at the moment of the treatment. In fact, it was considered that intracellular ATP level dictate cell decision to die by necrotic or apoptotic cell death [64, 65]. One of the signals which are provoked with DNA damage is PARP-1 activation and subsequent ATP depletion caused by PARP-1 mediated cleavage of NAD+. This event is a trigger for necrotic cell death. However, activated caspases cleaved the PARP-1, preventing necrotic signal and favor the execution of apoptotic process. On the other hand, the inhibition of caspases by intracellular inhibitors IAP together with continual PARP activity and ATP depletion resulted in necrosis [31]. As numerous biological phenomena, this one is not unidirectional. It was found that failure in PARP cleavage may also serve to apoptosis [66]. This paradox was ascribed to changes in pyridine nucleotide pool as well as in pool of ATP/ADP responsible for regulation of mitochondrial potential [67]. Atypical apoptosis was observed in L1210 leukemia cell line exposed to cisplatin. Different death profiles in cisplatin treated cells confirmed plasticity of signals involved in cell destruction and focus the attention to the molecules responsible for resistance to death as possible targets for the therapy. Having in mind that cisplatin is toxic agent against whom the cell can activate autophagy as protective process; the specific inhibition of autophagy by certain type of molecules could amplify the effectiveness of cisplatin [50].

Figure 4.

Mode of cell death induced by cisplatin: apoptosis (left) and necrosis (right).

1.8. Cisplatin in Immune Senzitization

One of the rarely mentioned but very important aspects of antitumor activity of cisplatin is based on the experimental data about its potential to amplified the sensitivity of malignant cells to one or the most potent and selective antitumor immune response mediated by TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand TRAIL [68, 69]. This molecule is produced by almost all immune cells involved in nonspecific as well as adoptive immune response. Unfortunately, in the moment when tumor is diagnosed, its sensitivity to natural immunity is debatable. In most of the situations, malignant cells became resistant to TRAIL-mediated cytotoxicity [70]. Moreover, it was confirmed that cisplatin promoted their sensitivity to TRAIL. Nature of its immune sensitizing potential is at least partly due to upregulation of expression of TRAIL receptors—DR4 and DR5 on the cellular membrane glioma, colon and prostate cell lines as well as downregulation of cellular form of caspase 8 inhibitor FLIP [68, 69]. In addition, presence of cysteine rich domen in the structure of TRAIL specific death receptors indicated possibility that cisplatin directly interact with them.

1.9. Resistance to Cisplatin and How to Surmount It

Resistance to cisplatin could be established at multiple levels, from cellular uptake of the drug through interaction with protein and DNA and finally activation of signals which lead the cell to death. Disturbed drug uptake, drug scavenging by cellular proteins, upregulation of prosurvival signals together with upregulated expression of antiapoptotic molecules such as Bcl-2 and BclXL, overexpressed natural inhibitors of caspases like FLIP and XIAP, diminished MAP signaling pathway or deficiency in proteins involved in signal transferring from damaged DNA to cytoplasm, enhanced activity of repair mechanisms and efficient redox system are features mainly responsible for unsuccessful treatment with cisplatin [33]. Well defined molecular background of the resistance to cisplatin point out the way on how to surmount it. It was already known that some of combined treatments of cisplatin with other chemotherapeutics such as 5-fluorouracil improved therapeutic response rates in patients with head and neck cancer [71, 72]. Furthermore, inhibition of NER DNA repair system, cotreatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDAC) such as trichostatin A (TSA) or suberoylanilide hydeoxamic (SAHA) [73], small molecules inhibitors of FLIP and XIAP as well as topoisomerase inhibitors strongly synergized with cisplatin, elevating its therapeutic potential.

2. Metallocenes in Anticancer Chemotherapy

Most of the metallodrugs used currently in chemotherapy treatment are based on platinum (cisplatin analogues), although as side effects are the weakest point in the use of cisplatin-based drugs in chemotherapy are the high number of side effects, many efforts are focused on the search of novel metal complexes with similar antineoplastic activity and less side effects as an alternative for platinum complexes. Transition-metal complexes have shown very useful properties in cancer treatment, and the most important work in chemotherapy with transition metals has been carried out with Group 4, 5, 6, 8, and 11 metal complexes.

From all the studied metal complexes, a wide variety of studies have been carried out for metallocenes which have become an alternative to platinum-based drugs.

According to the IUPAC classification metallocene contains a transition metal and two cyclopentadienyl ligands coordinated in a sandwich structure. These compounds have caused a great interest in chemistry due to their versatility which comes from their interesting physical properties, electronic structure, bonding, and their chemical and spectroscopical properties [74]. Academic and industrial research on metallocene chemistry has led to the utilization of these derivatives in many different applications such as olefin polymerization catalysis, asymmetric catalysis or organic syntheses, preparation of magnetic materials, use as nonlinear optics or molecular recognizers, flame retardants or in medicine [74].

Within medicine, metallocene complexes are being normally used as biosensors or as antitumor agents. Regarding their anticancer applicability, titanocene, vanadocene, molybdocene, and ferrocene have been traditionally used with very good results, however, recently also zirconocene derivatives have pointed towards a future potential applicability due to the increase of their cytotoxicity. All the other metallocene derivatives have been either not tested or have demonstrated no remarkable applicability in the fight against cancer.

In this part of the paper, we will briefly discuss separately the properties of metallocene derivatives of titanium, zirconium, vanadium, molybdenum, and iron.

2.1. Titanocene Derivatives

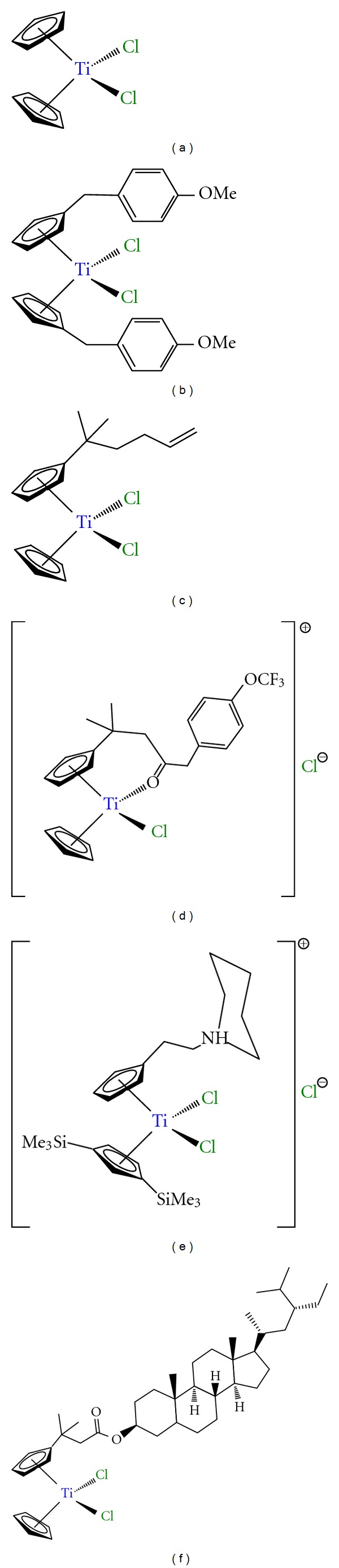

Titanocene derivatives are together with ferrocene complexes the most studied metallocenes in the fight against cancer. The pioneering work of Köpf and Köpf-Maier in the early 1980's showed the antiproliferative properties of titanocene dichloride, [TiCp2Cl2] (Cp = η 5-C5H5, Figure 5(a)). This compound was studied in phase I clinical trials in 1993 [75–77] using water soluble formulations developed by Medac GmbH (Germany) [78].

Figure 5.

Titanocene derivatives used in preclinical and clinical trials: (a) titanocene dichloride; (b) titanocene-Y; (c) alkenyl-substituted titanocene derivative; (d) titanocenyl complex; (e) titanocene derivative with alkylammonium substituents; (f) steroid-functionalized titanocene derivative.

Phase I clinical trials pointed towards a dose-limiting side effect associated to nephrotoxicity which together with hypoglycemia, nausea, reversible metallic taste immediately after administration, and pain during infusion, seemed to be the weakest part of the administration of titanocene dichloride in humans. On the other hand, the absence of any effect on proliferative activity of the bone marrow, one of the most common dose-limiting side-effect of nonmetallic drugs, was in interesting result that increased the potential applicability of this compound in humans.

Although phase I clinical trials were not as satisfactory as expected, some phase II clinical trials with patients with breast metastatic carcinoma [79] and advanced renal cell carcinoma [80] have been carried out observing a low activity which discouraged further studies.

However, after the recent work of many groups such as Tacke, Meléndez, McGowan, Baird, and Valentine the interest in this field has been renewed [81–85]. In this context a wide variety of titanocene derivatives with amino acids [86, 87], benzyl-substituted titanocene or ansa-titanocene derivatives [81], amide functionalized titanocenyls [88, 89], titanocene derivatives with alkylammonium substituents on the cyclopentadienyl rings [90–92], steroid-functionalized titanocenes [93], and alkenyl-substituted titanocene or ansa-titanocene derivatives (Figure 5) [94–96], have been reported with very interesting cytotoxic properties which enhance their applicability in humans. In particular, [Ti{η 5-C5H4(CH2C6H4OCH3)}2Cl2] (titanocene Y, Figure 5(b)) and its family, reported by Tacke and coworkers, have demonstrated to have extremely interesting anticancer properties which need to be highlighted.

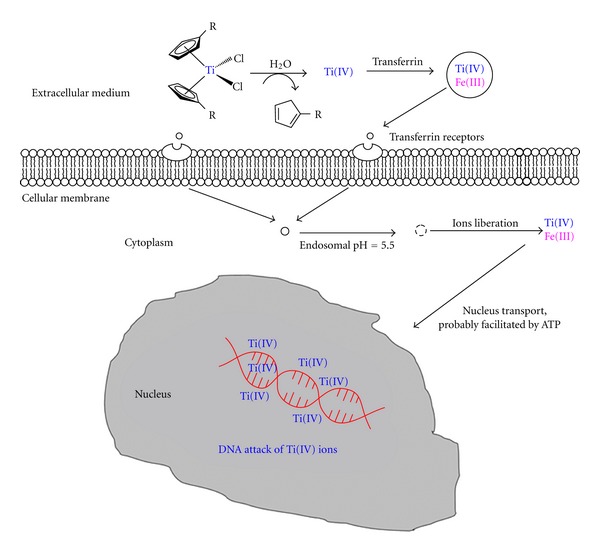

In general, the cytotoxic activity of titanocene complexes has been correlated to their structure, however, there are still several questions regarding the anticancer mechanism of titanocene(IV) complexes. According to the reported studies in the topic, it seems clear titanium ions reach cells assisted by the major iron transport protein “transferrin” [97–100], and the nucleus in an active transport facilitated probably by ATP. In a final step, binding of titanium ion to DNA leads to cell death (Figure 6) [101, 102]. However, recent experiments have shown interactions of a ligand-bound Ti(IV) complex to other proteins or enzymes [103–105], indicating alternatives in cell death mechanisms, which is currently leading to intensive studies by several research groups.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism of action of titanocene derivatives (adapted from Abeysinghe and Harding, Dalton Trans. 32 (2007) 3474).

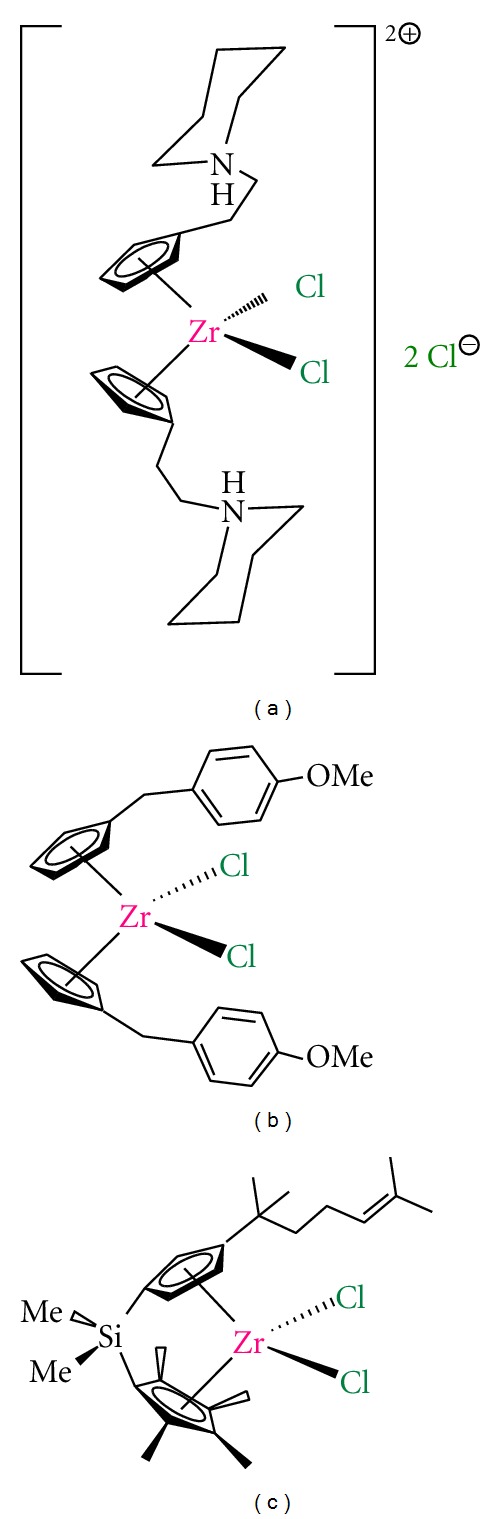

2.2. Zirconocene Derivatives

An alternative to titanium complexes may be zirconium(IV) derivatives which are in a very early stage of preclinical experiments. Already in the 1980's Köpf and Köpf-Maier showed the potential of zirconocene derivatives as anticancer agents and very recently, two different studies on zirconocene anticancer chemistry have been reported [106, 107]. These studies by Allen et al. [106] and Wallis et al. [107]have described the cytotoxic activity of different functionalized zirconocene complexes, observing an irregular behavior in the anticancer tests, from which only the complexes [Zr{η 5-C5H4(CH2)2N(CH2)5}2Cl2 ·2HCl] (Figure 7(a)) and [Zr{η 5-C5H4(CH2C6H4OCH3)}2Cl2] (zirconocene Y, Figure 7(b)) have shown promising activity that needs to be improved in order to apply them in anticancer chemotherapy.

Figure 7.

Zirconocene derivatives with anticancer activity: (a) zirconocene derivative with alkylammonium substituents; (b) zirconocene-Y; (c) alkenyl-substituted ansa-zirconocene complex.

In parallel, our research group reported the synthesis, structural characterization, catalytic behavior in the polymerization of ethylene and copolymerization of ethylene and 1-octene and the cytotoxic activity on different human cancer cell lines of a novel alkenyl substituted silicon-bridged ansa-zirconocene complex (Figure 7(c)) which proved to be the most active zirconocene complex on human A2780 ovarian cancer cells, reported to date [108].

There is still hard work to do in this field to find a suitable zirconocene complex with increased cytotoxic activity and good applicability in humans.

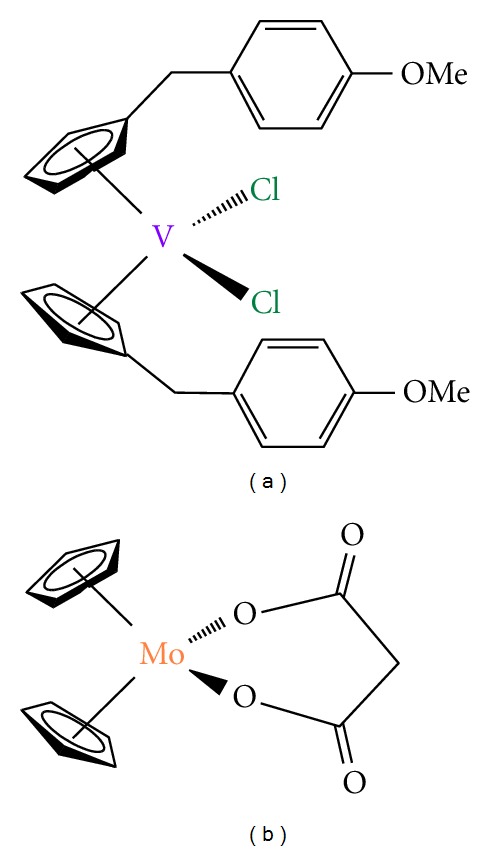

2.3. Vanadocene Derivatives

Vanadocene dichloride, [VCp2Cl2] (Cp = η 5-C5H5), was extensively studied in preclinical testing against both animal and human cancer cell lines, observing a higher in vitro activity of vanadocene(IV) dichloride on direct comparison with titanocene(IV) dichloride [109–111].

These results encouraged further preclinical studies which were restarted around eight years ago [112–114], and have been recently extended [115–118] with the study of the cytotoxic properties of vanadocene Y (Figure 8(a)) and similar derivatives. In addition, a comprehensive study of the cytotoxic activity of methyl- and methoxy-substituted vanadocene(IV) dichloride toward T-lymphocytic leukemia cells MOLT-4 has also been recently reported [119]. In most cases, vanadocene derivatives are more active than their corresponding titanocene analogues, however, the paramagnetic nature of the vanadium center, which precludes the use of classical NMR tools, makes the characterization of these compounds and their biologically active species more difficult. The need of the use of X-ray crystallography and other methods such as electron-spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy slows down their analysis and the advances in this topic.

Figure 8.

(a) Vanadocene-Y; (b) molybdocene carboxylate derivative.

2.4. Molybdocene Derivatives

After the work of Köpf and Köpf-Maier there were some evidences of the potential properties as anticancer agents of molybdocene dichloride derivatives. In recent years, the extensive work carried out by many different research groups confirmed the anticancer properties of molybdocene [120–124]. But not only the cytotoxic properties of these compounds have been reported, the hydrolysis chemistry of [MoCp2Cl2] has been intensively studied [125–127]. In the case of molybdocene derivatives the stability of the Cp ligands at physiological pH has led to the study of many different biological experiments with results which show new insights on the mechanism of antitumor action of [MoCp2Cl2] and some analogous carboxylate derivatives (Figure 8(b)) [117, 128–130].

2.5. Ferrocene Derivatives

The discovery of the cytotoxic properties of ferricinium salts on Ehrlich ascite tumors by Köpf and Köpf-Maier [131, 132] were an early breakthrough for the subsequent development of novel preparations of this class of anticancer agents.

There are different groups working in this field, however, to date, the most interesting work in the field of anticancer applications of ferrocene derivatives is being carried out by Jaouen and coworkers.

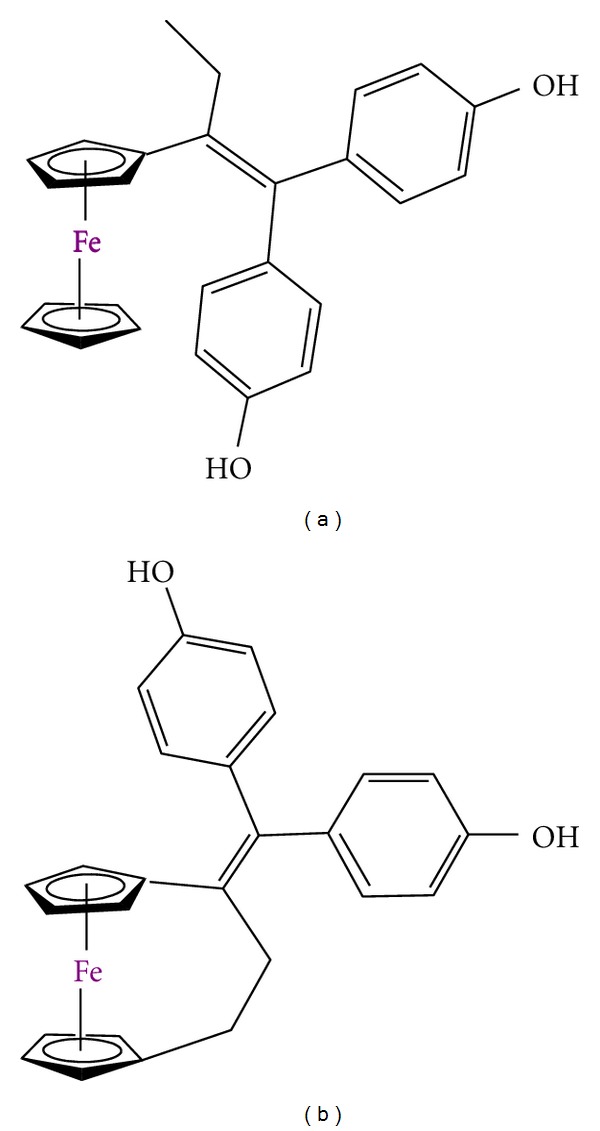

This group has published several reports on the synthesis of novel functionalized ferrocene derivatives “hydoxyferrocifens” which consist of the linking of the active metabolite of tamoxifen and ferrocene moieties (Figure 9(a)) [133, 134]. This novel class of compounds are able to combine the antioestrogenic properties of tamoxifen with the cytotoxic effects of ferrocene [135–137]. From all these complexes, the outstanding cytotoxicity of a ferrocene complex with a [3] ferrocenophane moiety conjugated to the phenol group (Figure 9(b)) is important to be remarked [138].

Figure 9.

Ferrocene derivatives used in preclinical trials: (a) hydroxyferrocifens; (b) ferrocene complex with a [3] ferrocenophane moiety.

In addition, ferrocene-functionalized complexes with steroids or nonsteroidal antiandrogens have also been reported to be very effective to target prostate cancer cells [139].

But not only the design and synthesis of novel ferrocene derivatives with different ligands and cytotoxic properties have been studied, several investigations on the cell death induced mechanism of these anticancer drugs have been reported. Thus, two different action mechanisms have been proposed for ferrocene derivatives, production of electrophilic species, and/or production of ROS species [140].

2.6. Future Tendencies in the Use of Metallocenes in Anticancer Chemotherapy

Almost all metallocene derivatives which have been studied either in preclinical or clinical trials are extremely hydrophobic to be intravenously administered, thus limiting their bioavailability for clinical applications.

Novel formulations of metallocene derivatives in macromolecular systems such as cucurbit(n)urils [140] or cyclodextrins [141] leading to a presumably higher applicability in humans.

In addition, using a different approach, but with the same goal of circumventing the solubility problems of metallocenes in biological media, several metallocene-functionalized MCM-41 or SBA-15 starting from different titanocene dichloride derivatives with anticancer activity have been reported and may be a good starting point for the development of novel metallocene-based drugs for the treatment of bone tumors [142–145].

3. Conclusions

One of the most potent antitumoral drugs cisplatin deserves special attention as exceptional of few with healing effect. Important role in the action of cisplatin is interaction with nuclear DNA and unfeasibility of the cell response to repair DNA strain containing covalently bonded dichloridoplatinum(II) moiety (nucleotide excision repair mechanism). Beside DNA, cisplatin might interact with other biomolecules (thioproteins, RNA) and in that way could be deactivated or even may possibly tune different signaling pathways involved in mediation of cell death, which is cell type specific. Namely, cisplatin has intense effects on signaling pathways facilitated by MAPs (e.g., ERK, JNK, p38). In recent years information on the cellular processing of cisplatin has essentially arisen. Knowledge collected from studies about biological effects of cisplatin and development of cisplatin resistant phenotype afford important clues for the design of more efficient and less toxic platinum and nonplatinum metal based drugs in cancer therapy. It is to be expected that nonplatinum metal compounds may demonstrate anticancer activity and toxic side effects noticeably different from that of platinum based drugs. Thus titanocene, vanadocene, molybdocene, ferrocene, and zirconocene revealed encouraging results in in vitro studies. These compounds might enter by different transport mechanism through cell membrane and distinctly interact with biomolecules than cisplatin. Notwithstanding the extensive applications of cisplatin in the new investigations will provide us with powerful facts for finding a novel efficient and nontoxic metallotherapeutics in anticancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (GNK, SGR), from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain (Grant no. CTQ2011-24346), and from the Ministry of Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (Grant no. 173013 DMI, SI).

References

- 1.Arnesano F, Natile G. Mechanistic insight into the cellular uptake and processing of cisplatin 30 years after its approval by FDA. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2009;253(15-16):2070–2081. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higby DJ, Wallace HJ, Albert DJ, Holland JF. Diaminodichloroplatinum: a phase I study showing responses in testicular and other tumors. Cancer. 1974;33(5):1219–1225. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197405)33:5<1219::aid-cncr2820330505>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hambley TW. Developing new metal-based therapeutics: challenges and opportunities. Dalton Transactions. 2007;21(43):4929–4937. doi: 10.1039/b706075k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamieson ER, Lippard SJ. Structure, recognition, and processing of cisplatin-DNA adducts. Chemical Reviews. 1999;99(9):2467–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr980421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giaccone G. Clinical perspectives on platinum resistance. Drugs. 2000;59(4):9–17. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059004-00002. discussion 37-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuertes MA, Alonso C, Pérez JM. Biochemical modulation of cisplatin mechanisms of action: enhancement of antitumor activity and circumvention of drug resistance. Chemical Reviews. 2003;103(3):645–662. doi: 10.1021/cr020010d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köberle B, Masters JRW, Hartley JA, Wood RD. Defective repair of cisplatin-induced DNA damage caused by reduced XPA protein in testicular germ cell tumours. Current Biology. 1999;9(5):273–276. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mamenta EL, Poma EE, Kaufmann WK, Delmastro DA, Grady HL, Chaney SG. Enhanced replicative bypass of platinum-DNA adducts in cisplatin-resistant human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Research. 1994;54(13):3500–3505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eliopoulos AG, Kerr DJ, Herod J, et al. The control of apoptosis and drug resistance in ovarian cancer: influence of p53 and Bcl-2. Oncogene. 1995;11(7):1217–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanov AI, Christodoulou J, Parkinson JA, et al. Cisplatin binding sites on human albumin. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(24):14721–14730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeConti RC, Toftness BR, Lange RC, Creasey WA. Clinical and pharmacological studies with cis diamminedichloroplatinum(II) Cancer Research. 1973;33(6):1310–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gately DP, Howell SB. Cellular accumulation of the anticancer agent cisplatin: a review. British Journal of Cancer. 1993;67(6):1171–1176. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishida S, Lee J, Thiele DJ, Herskowitz I. Uptake of the anticancer drug cisplatin mediated by the copper transporter Ctr1 in yeast and mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(22):14298–14302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162491399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alderden RA, Hall MD, Hambley TW. The discovery and development of cisplatin. Journal of Chemical Education. 2006;83(5):728–734. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timerbaev AR, Hartinger CG, Aleksenko SS, Keppler BK. Interactions of antitumor metallodrugs with serum proteins: advances in characterization using modern analytical methodology. Chemical Reviews. 2006;106(6):2224–2248. doi: 10.1021/cr040704h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volckova E, Evanics F, Yang WW, Bose RN. Unwinding of DNA polymerases by the antitumor drug, cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) Chemical Communications. 2003;9(10):1128–1129. doi: 10.1039/b301356a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad S. Platinum-DNA interactions and subsequent cellular processes controlling sensitivity to anticancer platinum complexes. Chemistry and Biodiversity. 2010;7(3):543–566. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knox RJ, Friedlos F, Lydall DA, Roberts JJ. Mechanism of cytotoxicity of anticancer platinum drugs: evidence that cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) and cis-diammine-(1,1-cyclobutanedicarboxylato)platinum(II) differ only in the kinetics of their interaction with DNA. Cancer Research. 1986;46(4):1972–1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munchausen LL, Rahn RO. Physical studies on the binding of cis dichlorodiamine platinum(II) to DNA and homopolynucleotides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1975;414(3):242–255. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(75)90163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eastman A. Characterization of the adducts produced in DNA by cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) and cis-dichloro(ethylenediamine)platinum(II) Biochemistry. 1983;22(16):3927–3933. doi: 10.1021/bi00285a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plooy ACM, Fichtinger-Schepman AMJ, Schutte HH. The quantitative detection of various Pt-DNA-adducts in Chinese hamster ovary cells treated with cisplatin: application of immunochemical techniques. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6(4):561–566. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger AE, Hartinger CG, Hamidane HB, Tsybin YO, Keppler BK, Dyson PJ. High resolution mass spectrometry for studying the interactions of cisplatin with oligonucleotides. Inorganic Chemistry. 2008;47(22):10626–10633. doi: 10.1021/ic801371r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zamble DB, Mu D, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Lippard SJ. Repair of cisplatin-DNA adducts by the mammalian excision nuclease. Biochemistry. 1996;35(31):10004–10013. doi: 10.1021/bi960453+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reardon JT, Vaisman A, Chaney SG, Sancar A. Efficient nucleotide excision repair of cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and bis- acetoammine-dichloro-cyclohexylamine-platinum(IV) (JM216) platinum intrastrand DNA diadducts. Cancer Research. 1999;59(16):3968–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson SW, Perez RP, Godwin AK, et al. Role of platinum-DNA adduct formation and removal in cisplatin resistance in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1994;47(4):689–697. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferry KV, Hamilton TC, Johnson SW. Increased nucleotide excision repair in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells: role of ERCC1-XPF. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2000;60(9):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fink D, Zheng H, Nebel S, et al. In vitro and in vivo resistance to cisplatin in cells that have lost DNA mismatch repair. Cancer Research. 1997;57(10):1841–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheeff ED, Briggs JM, Howell SB. Molecular modeling of the intrastrand guanine-guanine DNA adducts produced by cisplatin and oxaliplatin. Molecular Pharmacology. 1999;56(3):633–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaisman A, Varchenko M, Umar A, et al. The role of hMLH1, hMSH3, and hMSH6 defects in cisplatin and oxaliplatin resistance: correlation with replicative bypass of platinum-DNA adducts. Cancer Research. 1998;58(16):3579–3585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaney SG, Campbell SL, Bassett E, Wu Y. Recognition and processing of cisplatin- and oxaliplatin-DNA adducts. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2005;53(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cepeda V, Fuertes MA, Castilla J, Alonso C, Quevedo C, Pérez JM. Biochemical mechanisms of cisplatin cytotoxicity. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;7(1):3–18. doi: 10.2174/187152007779314044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henkels KM, Turchi JJ. Induction of apoptosis in cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant human ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Research. 1997;57(20):4488–4492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D, Lippard SJ. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4(4):307–320. doi: 10.1038/nrd1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juo ZS, Chiu TK, Leiberman PM, Baikalov I, Berk AJ, Dickerson RE. How proteins recognize the TATA box. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1996;261(2):239–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaneva J, Leuba SH, Van Holde K, Zlatanova J. The major chromatin protein his tone H1 binds preferentially to cis-platinum-damaged DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(25):13448–13451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kartalou M, Samson LD, Essigmann JM. Cisplatin adducts inhibit 1,N6-ethenoadenine repair by interacting with the human 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase. Biochemistry. 2000;39(27):8032–8038. doi: 10.1021/bi000417h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Söti C, Rácz A, Csermely P. A nucleotide-dependent molecular switch controls ATP binding at the C-terminal domain of Hsp90. N-terminal nucleotide binding unmasks a C-terminal binding pocket. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(9):7066–7075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peleg-Shulman T, Gibson D. Cisplatin-protein adducts are efficiently removed by glutathione but not by 5′-guanosine monophosphate. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123(13):3171–3172. doi: 10.1021/ja005854y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daino H, Matsumura I, Takada K, et al. Induction of apoptosis by extracellular ubiquitin in human hematopoietic cells: possible involvement of STAT3 degradation by proteasome pathway in interleukin 6-dependent hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2000;95(8):2577–2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguewa PA, Fuertes MA, Cepeda V, et al. Pentamidine is an antiparasitic and apoptotic drug that selectively modifies ubiquitin. Chemistry and Biodiversity. 2005;2(10):1387–1400. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Mijatovic S, Miljkovic D, et al. The antitumor properties of a nontoxic, nitric oxide-modified version of saquinavir are independent of Akt. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2009;8(5):1169–1178. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casini A, Gabbiani C, Mastrobuoni G, et al. Insights into the molecular mechanisms of protein platination from a case study: the reaction of anticancer platinum(II) iminoethers with horse heart cytochrome C. Biochemistry. 2007;46(43):12220–12230. doi: 10.1021/bi701516q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arnesano F, Natile G. “Platinum on the road”: interactions of antitumoral cisplatin with proteins. Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2008;80(12):2715–2725. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three akts. Genes and Development. 1999;13(22):2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fraser M, Leung BM, Yan X, Dan HC, Cheng JQ, Tsang BK. p53 is a determinant of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein/Akt-mediated chemoresistance in human ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2003;63(21):7081–7088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dan HC, Sun M, Kaneko S, et al. Akt phosphorylation and stabilization of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(7):5405–5412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viniegra JG, Losa JH, Sánchez-Arévalo VJ, et al. Modulation of PI3K/Akt pathway by E1a mediates sensitivity to cisplatin. Oncogene. 2002;21(46):7131–7136. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaul Y. c-Abl: activation and nuclear targets. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2000;7(1):10–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong J, Costanzo A, Yang HQ, et al. The tyrosine kinase c-Abl regulates p73 in apoptotic response to cisplatin-induced DNA damage. Nature. 1999;399(6738):806–809. doi: 10.1038/21690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harhaji-Trajkovic L, Vilimanovich U, Kravic-Stevovic T, Bumbasirevic V, Trajkovic V. AMPK-mediated autophagy inhibits apoptosis in cisplatin-treated tumour cells. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2009;13(9):3644–3654. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Requirement for ERK activation in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(50):39435–39443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cui W, Yazlovitskaya EM, Mayo MS, et al. Cisplatin-induced response of c-jun N-terminal kinase 1 and extracellular signal—regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 in a series of cisplatin-resistant ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2000;29:219–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Radovic J, et al. Aloe emodin decreases the ERK-dependent anticancer activity of cisplatin. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2005;62(11):1275–1282. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5041-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Radovic J, et al. Anti-glioma action of aloe emodin: the role of ERK inhibition. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2005;62(5):589–598. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4425-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mansouri A, Ridgway LD, Korapati AL, et al. Sustained activation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(21):19245–19256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sánchez-Perez I, Murguía JR, Perona R. Cisplatin induces a persistent activation of JNK that is related to cell death. Oncogene. 1998;16(4):533–540. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayakawa J, Ohmichi M, Kurachi H, et al. Inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase or c-Jun N- terminal protein kinase cascade, differentially activated by cisplatin, sensitizes human ovarian cancer cell line. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(44):31648–31654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103(2):239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pandey P, Raingeaud J, Kaneki M, et al. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase by c-Abl-dependent and -independent mechanisms. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(39):23775–23779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hernández Losa J, Parada Cobo C, Guinea Viniegra J, Sánchez-Arevalo Lobo VJ, Ramón y Cajal S, Sánchez-Prieto R. Role of the p38 MAPK pathway in cisplatin-based therapy. Oncogene. 2003;22(26):3998–4006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang D, Lippard SJ. Cisplatin-induced post-translational modification of histones H3 and H4. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(20):20622–20625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonzalez VM, Fuertes MA, Alonso C, Perez JM. Is cisplatin-induced cell death always produced by apoptosis? Molecular Pharmacology. 2001;59(4):657–663. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lieberthal W, Triaca V, Levine J. Mechanisms of death induced by cisplatin in proximal tubular epithelial cells: apoptosis vs. necrosis. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270(4):F700–F708. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.4.F700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eguchi Y, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Intracellular ATP levels determine cell death fate by apoptosis or necrosis. Cancer Research. 1997;57(10):1835–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou R, Vander Heiden MG, Rudin CM. Genotoxic exposure is associated with alterations in glucose uptake and metabolism. Cancer Research. 2002;62(12):3515–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herceg Z, Wang ZQ. Failure of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage by caspases leads to induction of necrosis and enhanced apoptosis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19(7):5124–5133. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hirsch T, Marchetti P, Susin SA, et al. The apoptosis-necrosis paradox. Apoptogenic proteases activated after mitochondrial permeability transition determine the mode of cell death. Oncogene. 1997;15(13):1573–1581. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ding L, Yuan C, Wei F, et al. Cisplatin restores TRAIL apoptotic pathway in glioblastoma-derived stem cells through up-regulation of DR5 and down-regulation of c-FLIP. Cancer Investigation. 2011;29:511–520. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2011.605412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vondálová Blanárová O, Jelínková I, Szöor A, et al. Cisplatin and a potent platinum(IV) complex-mediated enhancement of TRAIL-induced cancer cells killing is associated with modulation of upstream events in the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(1):42–51. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Stosic-Grujicic S, Nicoletti F, Mijatovic S. Resistance to TRAIl and how to surmount it. Immunology Research. 2012;52(1-2):157–168. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Decatris MP, Sundar S, O’Byrne KJ. Platinum-based chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: current status. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2004;30(1):53–81. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(03)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shelley MD, Burgon K, Mason MD. Treatment of testicular germ-cell cancer: a cochrane evidence-based systematic review. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2002;28(5):237–253. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(02)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim MS, Blake M, Baek JH, Kohlhagen G, Pommier Y, Carrier F. Inhibition of histone deacetylase increases cytotoxicity to anticancer drugs targeting DNA. Cancer Research. 2003;63(21):7291–7300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Long NJ. Metallocenes. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Korfel A, Scheulen ME, Schmoll HJ, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of titanocene dichloride in adults with advanced solid tumors. Clinical Cancer Research. 1998;4(11):2701–2708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christodoulou CV, Ferry DR, Fyfe DW, et al. Phase I trial of weekly scheduling and pharmacokinetics of titanocene dichloride in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16(8):2761–2769. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mross K, Robben-Bathe P, Edler L, et al. Phase I clinical trial of a day-1, -3, -5 every 3 weeks schedule with titanocene dichloride (MKT 5) in patients with advanced cancer: a study of the phase I study group of the association for medical oncology (AIO) of the German Cancer Society. Onkologie. 2000;23(6):576–579. doi: 10.1159/000055009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Müller BW, Müller R, Lucks S, Mohr W. Medac Gesellschaft fur Klinische Spzeilpräparate GmbH. US Patent 5, 296, 237, 1994.

- 79.Kröger N, Kleeberg UR, Mross K, Edler L, Saß G, Hossfeld DK. Phase II clinical trial of titanocene dichloride in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Onkologie. 2000;23(1):60–62. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lümmen G, Sperling H, Luboldt H, Otto T, Rübben H. Phase II trial of titanocene dichloride in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 1998;42(5):415–417. doi: 10.1007/s002800050838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meléndez E. Titanium complexes in cancer treatment. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2002;42(3):309–315. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Caruso F, Rossi M. Antitumor titanium compounds and related metallocenes. In: Sigel A, Sigel H, editors. Metal Ions in Biological System. Vol. 42. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker; 2004. (Metal Complexes in Tumor Diagnostics and as Anticancer Agents). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dabrowiak JC. Metals in Medicine. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Olszewski U, Hamilton G. Mechanisms of cytotoxicity of anticancer titanocenes. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;10(4):302–311. doi: 10.2174/187152010791162261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Bioorganometallic fulvene-derived titanocene anti-cancer drugs. Chemical Society Reviews. 2008;37(6):1174–1187. doi: 10.1039/b707310k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hernández R, Lamboy J, Gao LM, Matta J, Román FR, Meléndez E. Structure-activity studies of Ti(IV) complexes: aqueous stability and cytotoxic properties in colon cancer HT-29 cells. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2008;13(5):685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hernández R, Méndez J, Lamboy J, Torres M, Román FR, Meléndez E. Titanium(IV) complexes: cytotoxicity and cellular uptake of titanium(IV) complexes on caco-2 cell line. Toxicology in Vitro. 2010;24(1):178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gao LM, Matta J, Rheingold AL, Meléndez E. Synthesis, structure and biological activity of amide-functionalized titanocenyls: improving their cytotoxic properties. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2009;694(26):4134–4139. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gansäuer A, Winkler I, Worgull D, et al. Carbonyl-substituted titanocenes: a novel class of cytostatic compounds with high antitumor and antileukemic activity. Chemistry. 2008;14(14):4160–4163. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allen OR, Croll L, Gott AL, Knox RJ, McGowan PC. Functionalized cyclopentadienyl titanium organometallic compounds as new antitumor drugs. Organometallics. 2004;23(2):288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Allen OR, Gott AL, Hartley JA, Hartley JM, Knox RJ, McGowan PC. Functionalised cyclopentadienyl titanium compounds as potential anticancer drugs. Dalton Transactions. 2007;(43):5082–5090. doi: 10.1039/b708283p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Potter GD, Baird MC, Cole SPC. A new series of titanocene dichloride derivatives bearing chiral alkylammonium groups; Assessment of their cytotoxic properties. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2010;364(1):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gao LM, Vera JL, Matta J, Meléndez E. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of steroid-functionalized titanocenes as potential anticancer drugs: sex steroids as potential vectors for titanocenes. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2010;15(6):851–859. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0649-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gómez-Ruiz S, Kaluđerović GN, Prashar S, et al. Cytotoxic studies of substituted titanocene and ansa-titanocene anticancer drugs. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2008;102(8):1558–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gómez-Ruiz S, Kaluđerović GN, Žižak Ž, et al. Anticancer drugs based on alkenyl and boryl substituted titanocene complexes. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2009;694(13):1981–1987. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kaluđerović GN, Tayurskaya V, Paschke R, Prashar S, Fajardo M, Gómez-Ruiz S. Synthesis, characterization and biological studies of alkenyl-substituted titanocene(IV) carboxylate complexes. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 2010;24(9):656–662. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sun H, Li H, Weir RA, Sadler PJ. You have full text access to this content the first specific TiIV-protein complex: potential relevance to anticancer activity of titanocenes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 1998;37(11):1577–1579. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980619)37:11<1577::AID-ANIE1577>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Guo M, Sadler PJ. Competitive binding of the anticancer drug titanocene dichloride to N,N′-ethylenebis(o-hydroxyphenylglycine) and adenosine triphosphate: a model for TiIV uptake and release by transferrin. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions. 2000;1:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guo M, Sun H, Bihari S, et al. Stereoselective formation of seven-coordinate titanium(IV) monomer and dimer complexes of ethylenebis(o-hydroxyphenyl)glycine. Inorganic Chemistry. 2000;39(2):206–215. doi: 10.1021/ic990669a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guo M, Sun H, McArdle HJ, Gambling L, Sadler PJ. Ti(IV) uptake and release by human serum transferrin and recognition of Ti(IV)-transferrin by cancer cells: understanding the mechanism of action of the anticancer drug titanocene dichloride. Biochemistry. 2000;39(33):10023–10033. doi: 10.1021/bi000798z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Köpf-Maier P, Krahl D. Tumor inhibition by metallogenes: ultrastructural localization of titanium and vanadium in treated tumor cells by electron energy loss spectroscopy. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 1983;44(3):317–328. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(83)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Köpf-Maier P. Intracellular localization of titanium within xenografted sensitive human tumors after treatment with the antitumor agent titanocene dichloride. Journal of Structural Biology. 1990;105(1–3):35–45. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(90)90096-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tinoco AD, Incarvito CD, Valentine AM. Calorimetric, spectroscopic, and model studies provide insight into the transport of Ti(IV) by human serum transferrin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(11):3444–3454. doi: 10.1021/ja068149j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tinoco AD, Eames EV, Valentine AM. Reconsideration of serum Ti(IV) transport: albumin and transferrin trafficking of Ti(IV) and its complexes. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130(7):2262–2270. doi: 10.1021/ja076364+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pavlaki M, Debeli K, Triantaphyllidou IE, Klouras N, Giannopoulou E, Aletras AJ. A proposed mechanism for the inhibitory effect of the anticancer agent titanocene dichloride on tumour gelatinases and other proteolytic enzymes. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2009;14(6):947–957. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Allen OR, Knox RJ, McGowan PC. Functionalised cyclopentadienyl zirconium compounds as potential anticancer drugs. Dalton Transactions. 2008;(39):5293–5295. doi: 10.1039/b812244j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wallis D, Claffey J, Gleeson B, Hogan M, Müller-Bunz H, Tacke M. Novel zirconocene anticancer drugs? Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2009;694(6):828–833. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gómez-Ruiz S, Kaluderović GN, Polo-Cerón D, et al. A novel alkenyl-substituted ansa-zirconocene complex with dual application as olefin polymerization catalyst and anticancer drug. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2009;694(18):3032–3038. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Köpf-Maier P. Antitumor bis(cyclopentadienyl) metal complexes. In: Keppler BK, editor. Metal Complexes in Cancer Chemotherapy. Weinheim, Germany: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft; 1993. pp. 259–296. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Navara CS, Benyumov A, Vassilev A, Narla RK, Ghosh P, Uckun FM. Vanadocenes as potent anti-proliferative agents disrupting mitotic spindle formation in cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2001;12(4):369–376. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ghosh P, D’Cruz OJ, Narla RK, Uckun FM. Apoptosis-inducing vanadocene compounds against human testicular cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(4):1536–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Paláčková H, Vinklárek J, Holubová J, Císařová I, Erben M. The interaction of antitumor active vanadocene dichloride with sulfur-containing amino acids. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2007;692(17):3758–3764. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vinklárek J, Honzíček J, Holubová J. Interaction of the antitumor agent vanadocene dichloride with phosphate buffered saline. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2004;357(12):3765–3769. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vinklárek J, Paláčková H, Honzíček J, Holubová J, Holčapek M, Císařová I. Investigation of vanadocene(IV) α-amino acid complexes: synthesis, structure, and behavior in physiological solutions, human plasma, and blood. Inorganic Chemistry. 2006;45(5):2156–2162. doi: 10.1021/ic050687u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gleeson B, Claffey J, Deally A, et al. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of fluorinated derivatives of vanadocene Y. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2009;(19):2804–2810. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gleeson B, Claffey J, Hogan M, Müller-Bunz H, Wallis D, Tacke M. Novel benzyl-substituted vanadocene anticancer drugs. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2009;694(9-10):1369–1374. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gleeson B, Claffey J, Deally A, et al. Novel benzyl-substituted molybdocene anticancer drugs. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2010;363(8):1831–1836. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gleeson B, Hogan M, Müller-Bunz H, Tacke M. Synthesis and preliminary cytotoxicity studies of indole-substituted vanadocenes. Transition Metal Chemistry. 2010;35(8):973–983. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Honzíček J, Klepalová I, Vinklárek J, et al. Synthesis, characterization and cytotoxic effect of ring-substituted and ansa-bridged vanadocene complexes. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2011;373(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Waern JB, Harding MM. Bioorganometallic chemistry of molybdocene dichloride. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2004;689(25):4655–4668. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Waern JB, Dillon CT, Harding MM. Organometallic anticancer agents: cellular uptake and cytotoxicity studies on thiol derivatives of the antitumor agent molybdocene dichloride. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;48(6):2093–2099. doi: 10.1021/jm049585o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Waern JB, Harris HH, Lai B, Cai Z, Harding MM, Dillon CT. Intracellular mapping of the distribution of metals derived from the antitumor metallocenes. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2005;10(5):443–452. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Waern JB, Turner P, Harding MM. Synthesis and hydrolysis of thiol derivatives of molybdocene dichloride incorporating electron-withdrawing substituents. Organometallics. 2006;25(14):3417–3421. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Campbell KS, Foster AJ, Dillon CT, Harding MM. Genotoxicity and transmission electron microscopy studies of molybdocene dichloride. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2006;100(7):1194–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Toney JH, Marks TJ. Hydrolysis chemistry of the metallocene dichlorides M(η 5-C5H5)2Cl2, M = Ti, V, Zr. Aqueous kinetics, equilibria, and mechanistic implications for a new class of antitumor agents. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1985;107(4):947–953. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Balzarek C, Weakley TJR, Kuo LY, Tyler DR. Investigation of the monomer-dimer equilibria of molybdocenes in water. Organometallics. 2000;19(15):2927–2931. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kuo LY, Kanatzidis MG, Sabat M, Tipton AL, Marks TJ. Metallocene antitumor agents. Solution and solid-state molybdenocene coordination chemistry of DNA constituents. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113(24):9027–9045. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Abeysinghe PM, Harding MM. Antitumour bis(cyclopentadienyl) metal complexes: titanocene and molybdocene dichloride and derivatives. Dalton Transactions. 2007;(32):3474–3482. doi: 10.1039/b707440a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Harding MM, Mokdsi G. Antitumour metallocenes: structure-activity studies and interactions with biomolecules. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2000;7(12):1289–1303. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Campbell KS, Dillon CT, Smith SV, Harding MM. Radiotracer studies of the antitumor metallocene molybdocene dichloride with biomolecules. Polyhedron. 2007;26(2):456–459. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H, Neuse EW. Ferrocenium salts—the first antineoplastic iron compounds. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition in English. 1984;23(6):456–457. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Köpf-Maier P, Kopf H, Neuse EW. Ferricenium complexes: a new type of water-soluble antitumor agent. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 1984;108(3):336–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00390468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Top S, Tang J, Vessières A, Carrez D, Provot C, Jaouen G. Ferrocenyl hydroxytamoxifen: a prototype for a new range of oestradiol receptor site-directed cytotoxics. Chemical Communications. 1996;8:955–956. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Top S, Dauer B, Vaissermann J, Jaouen G. Facile route to ferrocifen, 1-[4-(2-dimethylaminoethoxy)]-1-(phenyl-2-ferrocenyl-but-1-ene), first organometallic analogue of tamoxifen, by the McMurry reaction. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 1997;541(1-2):355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Top S, Vessières A, Cabestaing C, et al. Studies on organometallic selective estrogen receptor modulators. (SERMs) Dual activity in the hydroxy-ferrocifen series. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2001;637–639(1):500–506. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Top S, Vessières A, Leclercq G, et al. Synthesis, biochemical properties and molecular modelling studies of organometallic Specific Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs), the ferrocifens and hydroxyferrocifens: evidence for an antiproliferative effect of hydroxyferrocifens on both hormone-dependent and hormone-independent breast cancer cell lines. Chemistry. 2003;9(21):5223–5236. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jaouen G, Top S, Vessières A, Leclercq G, McGlinchey MJ. The first organometallic selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and their relevance to breast cancer. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;11(18):2505–2517. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Plazuk D, Vessières A, Hillard EA, et al. A [3]ferrocenophane polyphenol showing a remarkable antiproliferative activity on breast and prostate cancer cell lines. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;52(15):4964–4967. doi: 10.1021/jm900297x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hillard EA, Vessières A, Jaouen G. Ferrocene functionalized endocrine modulators as anticancer agents. Topics in Organometallic Chemistry. 2010;32:81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Buck DP, Abeysinghe PM, Cullinane C, Day AI, Collins JG, Harding MM. Inclusion complexes of the antitumour metallocenes Cp2MCl2 (M = Mo, Ti) with cucurbit[n]urils. Dalton Transactions. 2008;(17):2328–2334. doi: 10.1039/b718322d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Pereira CCL, Diogo CV, Burgeiro A, et al. Complex formation between heptakis(2,6-di-O-methyl)-β-cyclodextrin and cyclopentadienyl molybdenum(II) dicarbonyl complexes: structural studies and cytotoxicity evaluations. Organometallics. 2008;27(19):4948–4956. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pérez-Quintanilla D, Gomez-Ruiz S, Žižak Ž, et al. A new generation of anticancer drugs: mesoporous materials modified with titanocene complexes. Chemistry. 2009;15(22):5588–5597. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kaluđerović GN, Pérez-Quintanilla D, Sierra I, et al. Study of the influence of the metal complex on the cytotoxic activity of titanocene-functionalized mesoporous materials. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2010;20(4):806–814. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kaluđerović GN, Pérez-Quintanilla D, Žižak Ž, Juranić ZD, Gómez-Ruiz S. Improvement of cytotoxicity of titanocene-functionalized mesoporous materials by the increase of the titanium content. Dalton Transactions. 2010;39(10):2597–2608. doi: 10.1039/b920051g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.García-Peñas A, Gómez-Ruiz S, Pérez-Quintanilla D, et al. Study of the cytotoxicity and particle action in human cancer cells of titanocene-functionalized materials. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2012;106(2):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]